MANAGING YOUR CAREER

HOW TO SPOT THE GOOD BRIEFS

If your advertising career is to thrive, the main thing you’ll need (apart from being good) is good briefs to work on.

A good brief is one that offers the chance of doing great work. Often, it’s “who it’s for” that makes a brief an opportunity. Certain clients such as Volkswagen, Sony, Nike, Adidas, Levi’s, and Budweiser buy outstanding work all over the world, year after year. (There are also certain brands that regularly do great work in one country only—like Harvey Nichols and The Economist in the UK; Skittles and Burger King in the US.)

Your agency may not have any of these particular accounts, but it will still have one or two clients that buy award-winning work, or at least do work that is interesting.

Traditionally, great work comes more often in certain categories—beer, cars, and sportswear spring to mind. Whether that’s because these brands primarily target blokes and it’s largely blokes on awards juries…I wouldn’t like to say.

AND SPOT THE DOGS

As well as knowing what the good accounts are, you have to know which are your agency’s dogs. The toilet cleaners, athlete’s foot treatments, and shampoo accounts are usually, how can I put it, “creatively challenged”?

All creatives claim they like a challenge, but given the choice between a brief that’s a huge challenge and another that’s a massive opportunity, they’ll pick the opportunity every time. In other words, they take Nike over the toilet cleaner ten times out of ten. Of course, the person who does the first great piece of advertising for a brand that’s never previously had any gains great kudos. But the odds are loooooooooooooooooooong.

LOOKING FOR THE OPPORTUNITIES

In some cases, an account throws up a mixture of good and bad briefs. For example, a supermarket might do eight or ten super-dull “value” ads and one sumptuous brand ad a year.

Also, an average brand can suddenly present a good opportunity if a planner comes up with a really interesting strategy for it, or if sales dip and they need to do something dramatic.

The amount of money the client spends makes a difference too.

Maybe it shouldn’t, but it does. Car brands spend big; that means they are important to the agency, the agency puts their top people on the account and good ads get made. Everyone likes to work on the accounts with big production budgets. Money isn’t everything, and is not essential for producing great work, but if you do have it, then you have the choice of whether to spend it or not. Money gives you options.

There’s an inherent media bias also, in that creatives tend to get more excited by TV briefs than any other kind. Next on the list is typically posters, followed by print, digital, and radio. Individual preferences may vary, of course.

The final factor is timing. If a brief has been in the agency for a long time, and hasn’t been cracked, and the client is now desperate, then that’s a good time to work on it. Conversely, if there is plenty of time on a project, then there’s plenty of time to waste before anything needs to happen. Avoid.

Above all, don’t believe what any account handler, planner, or traffic person says about a brief. They’ll always tell you it’s great. They will always tell you the client wants to do something really different on this one. And they will always tell you that the ECD has requested you personally for it. You can’t blame them for wanting to get you excited about the project—they’re just doing their job. But you must use your own judgement, and exercise caution.

HOW TO GET ASSIGNED BETTER BRIEFS

Having said all that, few creatives get the choice of whatever briefs they want to work on. Some creatives, particularly in the US, and particularly on larger accounts, may be permanently assigned to a certain client. Most CDs are. The average creative “floats” but that doesn’t mean he’s “free;” it just means he can be assigned to any project for any client in the building.

And if there’s one process within an agency that’s frustratingly mysterious to creatives, it is the question of how briefs are assigned. Nearly all creatives believe they aren’t getting fair treatment, and fear that another team down the hall is getting all the best briefs.

They probably are. Although no ECD would admit it, there’s a pecking order in any creative department. Sometimes an exciting brief might go to both a senior and a junior team, to see what they each come up with. But usually the “top teams” get the big brand TV spots, and the junior or lesser-rated teams get the trade ads.

Hence if you are a young team, just starting out, you will probably be given less prestigious briefs at first. This may seem unfair, but from the agency’s point of view, they want the projects that are high-profile and high-stakes to go to their most experienced teams, since it’s more important that the agency gets them right.

If you aren’t such a young team any more, an easy way to tell how you stand within an agency is simply by the quality of the briefs you are getting. If you aren’t getting good briefs, then they don’t rate you. It’s that simple, I’m afraid.

However, it’s not terminal. The solution is the same, whatever your age, whatever your level of experience. Try to shine on the briefs you’re assigned to, but work on the more exciting briefs as well, unofficially. If your entire day is taken up with your official briefs, then you may need to work evenings and weekends if you want to progress.

A very few agencies don’t like teams working on briefs they’re not officially assigned to. If that is the case, only show work if you’re sure it’s brilliant—brilliant enough to make them forget you “stole” the brief.

But most agencies are delighted if teams work on a brief unofficially—it gives them more options. Just follow the house rules on how discreet you have to be.

Not many workplaces are as meritocratic as an ad agency. Do the job on a few of the agency’s high-profile projects and you will zoom up the hierarchy, scoring better and better briefs as you go.

And if you never want to get a bad brief again, keep cracking the good ones.

WORKING OUT WHICH MEDIUM IS RIGHT FOR YOU

THE HIERARCHY OF MEDIA

As your career progresses, you may focus on different media.

Typically, a beginning team gets mostly print, radio, and digital briefs, before “graduating” to TV.

There’s a perception that TV is harder.

And there is some truth in that. For one thing, there are simply more steps in the process of a TV shoot—like editing and grading—which aren’t part of a print shoot.

There’s more to learn.

The budget is also bigger for a TV ad, so it’s higher pressure. There are more people involved, so it’s more complicated. And there are more levels of approval to get through, both on the client side and in the agency (sometimes it’s more difficult getting a big TV ad through your agency than through the client—the managing director, head of planning, chairman…they all want a say in the TV, but for some reason, not the radio). Senior teams have more experience of dealing with this kind of pressure and politics; hence creative directors prefer senior teams for big TV ads.

THE HIERARCHY OF BRIEF-DIFFICULTY

As well as this unofficial hierarchy of media, there’s a hierarchy of brief-difficulty too. The hardest brief is for a new brand campaign, since it normally involves heavy-duty strategic thinking (e.g. “What should T-Mobile stand for?”). Product briefs are a little easier, since the brand personality has already been established, and you’re only devising the strategy for one product, not a whole brand (e.g. “How do we advertise T-Mobile’s new Pay Monthly package?”). The next easiest are “offer” ads (“15% off T-Mobile’s new Pay Monthly package”) and the easiest of all are tactical ads (ads used “tactically” to capitalize on a specific event or occasion, e.g. “15 percent off T-Mobile’s new Pay Monthly package if you sign up on April 1st—genuine offer, not an April Fool!”).

You’ll notice the difficulty is in proportion to how open the brief is. The question of what T-Mobile should stand for, for example, has hundreds of possible answers, so the CD would assign this brief to one of his most experienced teams, because he trusts they will hunt high and low to find a good one. But since “15 percent off when you sign up on April 1st” is much more limiting, with maybe only one or two possible angles, he’s more happy to assign it to a junior team.

Other supposedly “easier” briefs could include a small-space print ad, a trade ad, a digital banner, or a tactical radio ad. While these briefs can sometimes present good opportunities, there are fewer creative options available, which does make them more straightforward. And these are the sorts of briefs most teams start off with.

VARIETY AND PREFERENCE

Having said the above, many CDs like to put both a senior team and a junior one on a big brand TV ad. They reason that while the senior team is more likely to crack it, the junior team may come up with something fresher.

This means that while you may find yourself doing some big TV ads quite early in your career, a more typical path is for teams to do more print at the beginning and more TV later.

Along the way, you may develop a preference for one particular medium. Some creatives just love the instant hit of the poster. Some are interactive gurus who have little time for “old media.” And one leading radio writer told me he gravitated toward that medium because he had “the visual sense of Blind Lemon Jefferson.”

If you feel a strong pull toward one medium, you may want to consider a career as a specialist. For example, in many countries there are specialist radio production houses, or pure digital agencies.

But even generalists—and that’s most creatives—are allowed to have a favorite medium. Some creatives are regarded as “digital natives” or “a great print team,” but still do everything.

The only caveat is that if you want to become a creative director, it definitely helps to have proved your ability across a variety of media. There’s a feeling that if you’ve never done a good TV ad, how can a team take you seriously when you’re advising them how to make theirs better?

BRIEFS

(IN ORDER OF DIFFICULTY)

· New brand campaign

· Product brief

· “Offer ads”

· Tactical ads

SELF-INITIATED PROJECTS OR CHIP SHOP ADS

A few years ago, there was a spate of award-winning ads in the UK for chip shops. One example famously featured the magnificent USP that “Other fish ‘n’ chip shops don’t give a fork.”

Why did the nation’s chip shops suddenly (and simultaneously) request witty, highly creative advertising? The answer is that they didn’t. What happened was that these ads were created by creative teams for the sole purpose of their own self-advancement—i.e. to win awards—and the mini-boom in fried-takeaway advertising led to such work being dubbed “chip shop ads.” Another term for the practice is scam ads or, in some countries, ghost ads.

If a legitimate ad is defined as one that had a proper airing in legitimate media, then I would estimate that at least a third of the adverts that win lions in the press and poster categories at Cannes are scam.

TYPES OF SCAM

The most common scam is when an agency creates a press ad for a client, and then “accidentally” enters it into the poster awards as well.

Another widespread scam is when an agency proposes a campaign for one of its clients, and the client loves it—except for one execution, which they despise. This is usually the bravest and most interesting one. To keep the agency happy, the client agrees to run this additional execution in one publication only; purely so it qualifies for entry to awards (ads that haven’t run can’t be entered). This is almost a legitimate ad. It was requested by the client, approved by the client, paid for by the client, and genuinely appeared in the media. However, the definition does become a little stretched when a super-sexy ad for a luxury 4x4 turns up in a knitting magazine, because the client didn’t want to splash out for space in a more suitable (and expensive) publication. Or when an additional TV ad that the client didn’t like, that was shot at the same time as the ones they did like, runs at 3am on the fishing channel. Believe me, this happens a lot.

These “self-initiated” ads are my own. In both cases the client approved the executions and paid for them to appear, so I’d argue they are on the right side of the spec vs scam dividing line.

And it gets worse. What if a client refuses to pay for the ad to run? The agency pays. And if the client hates the ad so much, they won’t approve it to run at all? The agency pays for it to run, and doesn’t tell the client it has. Sometimes, an agency makes an ad for one of its clients, pays for the ad to run, and enters it into awards schemes, all without the client even being aware of its existence.

That’s a bit like someone stealing your dog, giving it an extreme makeover, and entering it for a dog show… all without you knowing it’s left the house.

Sounds crazy, but there are highly publicized cases that fit exactly that template.

In 2008, a TV commercial for the JC Penney clothing store was awarded a Bronze Lion at Cannes. The only problem was that JC Penney had never seen the script, didn’t know the ad was being shot, hadn’t paid for it to run, and only discovered its existence when they heard it had won the Lion, at which point they became furi-ous, since the ad’s subject matter—it showed two teens “speed undressing”—did not reflect the chain’s wholesome family values. The Lion was returned.

For years there’s been a rumor that one highly award-winning agency has an entire “shadow department” of creative teams dedicated solely to producing scam ads. The creatives working on the agency’s real clients are said to sit on a separate floor, and aren’t even allowed to talk to the “just for Cannes” teams.

This story is probably made up. But it gets told and retold, like an ad industry “urban myth,” because it taps into a genuine fear—that our industry is riddled with scam. And let’s face it, the awards schemes are full of 48-sheet posters for dog obedience classes and language schools—ads that were created by creatives on their Macs, specifically to win awards, which were never approved by any client, and almost certainly never ran.

Nancy Vonk, co-chief creative officer of Ogilvy Toronto, told Creativity magazine:

“Scams taint every show and burn clients at a time when there is a bigger appetite to endorse award-winning work. It’s an unfortunate burden on those who have to keep an eye out for anything that smells fishy. So: bar the agency with their name on the scam from entering the show the next year. Display scams prominently on the awards show site for public shaming. And all entries need a client signature in the first place. This wouldn’t solve everything; it’s a pain and the shows would have to be OK with losing the next year’s entry fees. But any answer to this is going to hurt.”

Some countries are worse for scams than others. I once served on an advertising awards jury with another juror who was from Singapore. He explained to me that he wouldn’t be voting for any ads at all from his own country, because he “knew” they were all scam. India and Thailand are also getting a bad reputation. An Asia-based CD admits:

“There’s no doubt that a few people here have built healthy careers on the back of print ads that the client would barely recognize. They’d justify it in a number of ways: raising the standards of advertising in backward local markets; showing potential clients what the agency is capable of; and the need to compete creatively with Europe and America on far smaller budgets.”

However, he contends that scamming is less prevalent now than it used to be.

“It’s unfortunate that there’s so much suspicion about Asian print work now, since it means some work is unfairly dismissed as scam, when it’s genuine.”

In actual fact, no country is immune. Plenty of scam ads come out of the UK, US, Australia, and Germany.

The industry is split on the morality of the scam issue. Some view it as a harmless way for ambitious creatives, who feel they’re not getting sufficient creative opportunities on their agency’s existing clients, to showcase their talent. Others view it simply as cheating. They liken it to the problem of drugs in sport, and argue that every award that goes to a scam ad means an award being taken away from a team that has played by the rules.

This book is not a work of moral philosophy, so I’m not going to advise you on what you should and shouldn’t do. However, I will tell you what I personally feel to be sensible and acceptable practice.

First of all, if your agency has many clients that offer good creative opportunities, then you shouldn’t be trying to do scam ads at all. What I mean is that if you are working at Abbott Mead Vickers in London, why would you waste your time approaching the local chip shop when The Economist has such a great advertising heritage and is constantly crying out for great posters?

But if your agency does not have any good clients, then you are quite within your rights to go out and get one yourself. Actually, the whole exercise can be really good fun.

HOW TO MAKE A SPEC AD

1 First of all, think of a great idea for an advert. It’s often easiest if it’s a print ad, just because costs are lower in print and it’s easier to pull favors, but it could also be for TV or ambient.

2 Next, get it shot. That’s right; you get it shot before you show the client. That’s because you only want the ad to get made exactly how you want it—your vision, free from all the usual compro-mises. For a print ad, the best way to do this is to find a hungry young photographer who is happy to shoot something for free. You can even get a TV ad shot for free—ask your TV department if they know of any young directors looking to make “test films.” Many production companies are actively looking to put money into getting a test film shot, because if it comes out great, it can launch a director’s reputation, and lead to high-paying glamorous jobs for him.

3 Because you want to make the ad before you show it to a client, make sure you choose a category that has many potential clients. I once shot a spec ad for a bed store, based around the territory of “beds so comfortable, you’ll never have a nightmare again.” The first image depicted a typical nightmare—being trouserless in public. At the first bed store we took it to, the manager liked the idea. Hence the name on the bottom of the ad became Alphabeds. However, if Alphabeds hadn’t liked it, the ad could have worked equally well for BettaBeds or Comfort Beds.

4 But if you had come up with an ad campaign for the Tower of London, say, based on the idea of “the most remarkable tower since Babel,” then if the people at the Tower of London don’t like it, you are in trouble, since there is no other tourist attraction in London that is also a tower.

If a friend of yours has a store or a small business, then so much the better. Go see them. Yes, it’s slightly easier to sell a campaign when the client is your mate or your uncle…but for me, that’s not cheating, it merely replicates real-world conditions—every agency finds it easier to sell to clients they are good friends with.

But if you don’t know anyone, it doesn’t matter. Any pet store or local hairdresser will be surprised and delighted to be offered a free ad campaign. Just ring them up. It’s not nearly as hard as it sounds, and it’s actually great fun to be your own account handler for a change. On the understanding that they will pay for the ad to run at least once in legitimate media, you let the client have the artwork at no cost.

Only once the whole campaign is signed, sealed, and delivered do you tell your creative director about the project. Hopefully, the ad has come out well and he will be happy to put the agency’s name to it. Bringing it under the agency’s wing is important, because you want the agency to pay the (considerable) costs of awards entries.

Don’t forget to PR it too. Because this isn’t a normal agency project with all the machinery of an account team behind it, it’s up to you to talk through the campaign with your agency’s PR person. Or simply send it out yourself to the trade press, Archive magazine, and the ad blogs.

Getting awards and PR gives you a maximum return on your effort. But even if those don’t come off, you’ll still have a great ad for your book, and you’ll learn as much as you would on six normal campaigns—so it’s definitely worth doing. But only in the early years of your career.

If you’re still doing spec ads at age 35, something has gone wrong.

PITCHES

While some clients show huge loyalty—for example, Ogilvy has handled the advertising for American Express since 1962—others change agency more often than P. Diddy changes his name.

Reasons include a client unhappy with the agency’s work, a breakdown in relationship between the two parties, or a new marketing director who wants to take the brand in a new direction.

Agency bosses wine and dine clients who they think might one day put their business up for pitch, and buy them Christmas presents. One agency I know buys Christmas trees. Fully loaded.

Pitches are incredibly important to an advertising agency. There’s a perception that if an agency isn’t growing, it’s dying.

And since people who work in advertising are highly competitive, pitches get their juices flowing. The proof is that their second question—right after “what are we pitching for?” is always “who are we up against?”

However, fundamentally, creatives want to make ads. And the work produced for a pitch rarely ends up getting made. Pitch work is intended as a demonstration of the kind of work the agency could do, and no one really expects a new brand campaign to be cracked in two weeks.

Sure, there’s an excitement to a pitch, a camaraderie. Plus there’s usually a big night out to celebrate the pitch coming to an end…and an even bigger one if you win. But many creatives resent the late nights, cold pizza, and time wasted when they could have been making real ads.

I’m sure agency managing directors would be utterly appalled to read this, and would rain blows on me like a piñata if they thought I was advising creatives not to try hard on pitches.

Luckily, I’m not. Pitches are so important to the agency in general, you must put a big effort in, or be seen as a dangerous anarchist. Put any concerns that it’s a waste of time right to the back of your mind, and go all out to win.

The biggest contribution a creative can make to winning a pitch is to come up with “a line.”

Clients often deny they want a line, agencies claim they’re not trying to think of one, and consumers are rarely interested in them when they appear.

And yet the power of a single sentence, which sums up what an entire brand stands for…

What could Guinness say to Abbott Mead Vickers after they showed them “Good Things Come To Those Who Wait” other than thank you, here’s our money, please go and make the campaign?

AWARDS

John O’Keeffe, global CD of the WPP group, once went to a restaurant in Cannes, and liked their steak-frites so much he returned the next night. But this time, the bill had doubled. When O’Keeffe queried it, the waiter explained “Monsieur, the festival ’as begun.”

The people who organize Cannes, D&AD, The One Show, and the Clios, charge advertising agencies hundreds of dollars to enter each piece of work. To order an extra Cannes lion (e.g. for the client) costs $1150. And as discussed, some agencies spend a fortune entering work that was especially created for awards shows, and never ran in the real world.

Even the way awards are determined is occasionally corrupt, with work from jury members’ own agencies getting a suspiciously large share.

However, if you want to have a successful career, you need to win awards.

The times in my career when I got a pay rise all followed winning awards. The times when headhunters contacted me about jobs at other agencies followed winning awards. The times when I started to get better briefs all followed winning awards too.

And I’m no special case. The evidence for the importance of awards is as solid as the evidence for evolution or gravity.

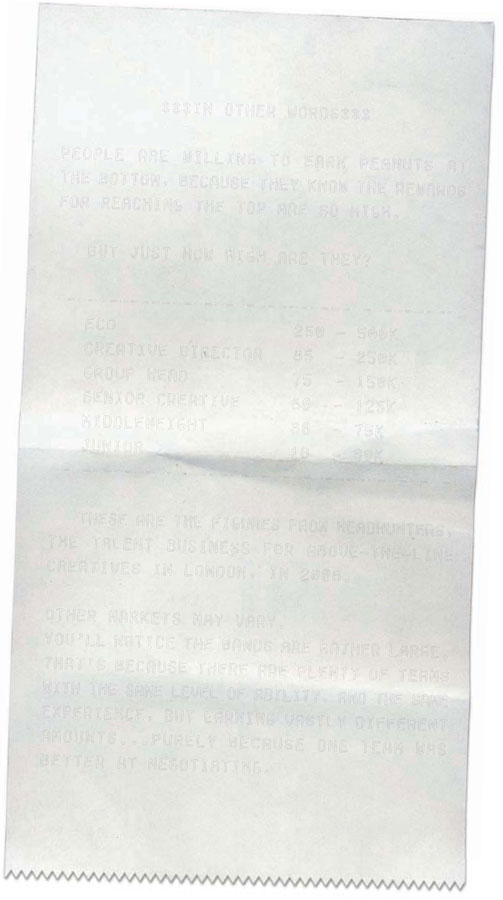

Just walk around any creative department and look at people’s shelves. Generally, the ECD has the most awards. Then the creative directors. Then the senior teams. Then the middleweights. And then the juniors. In other words, the more awards you have, the higher up the hierarchy you rise. More money, more responsibility, more opportunities.

That is fact.

SHOULD AWARDS BE AS IMPORTANT AS THEY ARE?

The question of whether awards should have the importance they do is a completely separate one.

It’s commonly stated, for example, that creatives ought not to care about awards, but effectiveness. Personally, I find it annoying that this debate is still going on, since study after study has shown an extremely strong correlation between award-winning work and effective work. Also, whether an ad works or not is a function of so many things other than its creative quality—for example, the strategy may be wrong, or the media placement flawed.

Asking for creatives to be judged on effectiveness is like asking strikers to be judged on the number of clearances they make in their own penalty area. Yes, it’s great if a striker can do that. But they must primarily be judged on their goals.

Some say awards exist because advertising creatives have egos the size of hot-air balloons. Again, I think that’s unfair. There are awards in the movie industry, the car industry…for all I know, there’s an award for accountant and doctor of the year as well.

And awards are arguably more necessary in our business than in certain other human endeavors such as athletics, motor racing, and typing contests, which offer a simple way to see who the winner is—the first person to finish. Advertising doesn’t have an objective measure like that.

And since the jury system is good enough for judging murder trials, it ought to be good enough for judging adverts. Of course the potential for anomalies exists, as with any jury. But because the question of “What is good work?” will always be a matter of opinion, it seems to me that referring to a jury of experts in the field is, while imperfect, the best system we are going to get.

Some creatives (and some agencies) don’t care about awards at all. They view them as solid-metal tokens of our insecurity; and they may be right.

But whether they really are a valid way of judging creatives’ merits or not, they are what the industry will judge you on.

WHAT WORK WINS AWARDS?

So if awards are that important, how do you win them?

There is absolutely no mystery about the type of work that juries go for.

And these criteria are typically the ones any creative would tell you make for an outstanding piece of communication: simple, engaging, impactful, rewarding, relevant, original, and produced to a high executional standard.

Some creatives complain there’s a “formula” to award-winning work—like a print ad that consists of nothing but an image with a visual twist, and the client’s logo placed small in the corner.

It’s probably true that there’s a certain type of work that does well at Cannes—the juries are international, hence work that is purely visual and requires no understanding of foreign languages or cultures will connect with more judges.

You could view this type of work as non-groundbreaking. Perhaps it is. Nevertheless, if it represents a really first-class example of our craft, then I don’t see any reason why it shouldn’t win awards.

However, the type of work that wins the truly prestigious awards (e.g. Cannes Grand Prix, D&AD Gold) is often work that genuinely is groundbreaking. That means it doesn’t follow the usual formulas, but redefines its medium, or its category, in some way.

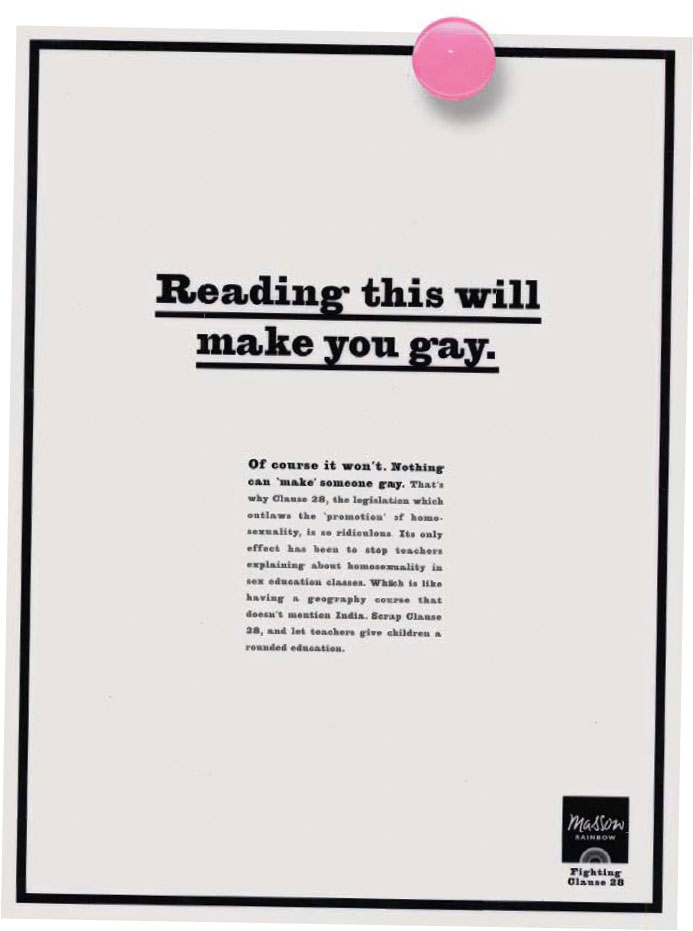

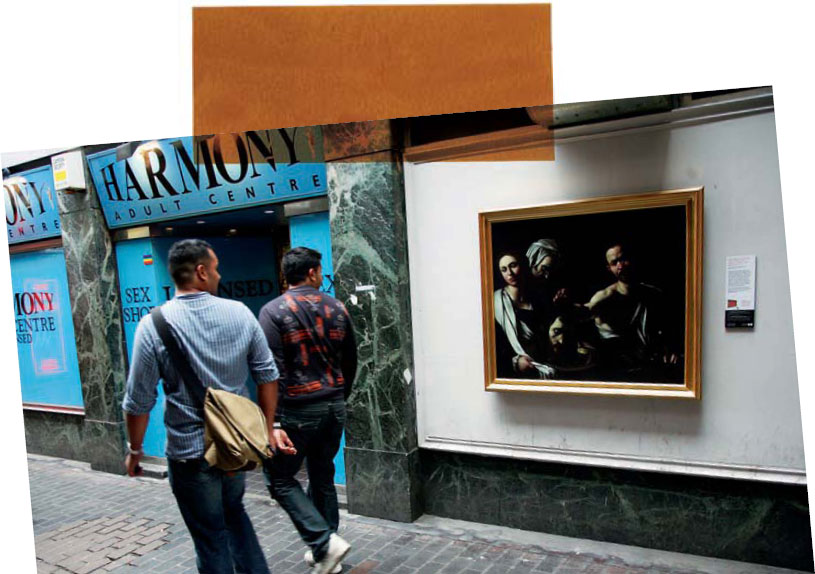

For example, the poster campaign for Britain’s National Gallery, which won a rare “black pencil” at D&AD in 2008, didn’t use conventional posters at all, but instead took the artworks themselves out into the streets of London...

Writing adverts. It’s a tough job, but somebody has to do it.

And of course, that somebody is not going to do it for free.

Peter Mayle, a former ad-man who has since found fame as the author of A Year in Provence, describes how he felt when he was offered his first creative directorship. “I decided to give it a go,” he says. “It was exciting to have been elevated so quickly. I was only 26, I was earning twice what the prime minister got paid, and I owned a house on Sloane Square.”

Wonderful story.

But that was 1965.

Since then, house prices have gone north, and advertising salaries have gone south. The reasons are too depressing to go into, but suffice it to say, the days when creatives drove Ferraris are long gone.

The book Freakonomics describes advertising as a “second-tier glamour profession” (behind movies, sports, music, and fashion). But the way salaries are heading, I fear we may soon reach Tier 3.

People who work in advertising still earn, on average, a pretty decent wage. Less than bankers, lawyers, or management consultants; more than plumbers, teachers, or journalists.

However, in the early days of your career, you should be aware that you will earn much less than all the above-mentioned.

Why? As Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner describe so brilliantly in Freakonomics, entrants to glamour industries;

“throw themselves at grunt jobs that pay poorly and demand unstinting devotion. An editorial assistant earning $22,000 at a Manhattan publishing house, an unpaid high-school quarterback, and a teenage crack dealer earning $3.30 an hour are all playing the same game, a game that is best viewed as a tournament.”

“The rules of a tournament are straightforward. You must start at the bottom to have a shot at the top...You must be willing to work long and hard at substandard wages. In order to advance in the tournament, you must prove yourself not merely above average but spectacular.”

The first couple of times I moved job, I failed to lie about my salary. Big mistake.

In each case, the CD asked us what we were earning, and then offered us a small increase over that—about 5 percent more—giving some excuse about how budgets were tight, but if we joined on this initially rather low amount, he would find more money for us soon.

What I later learned is that creative directors assume you are lying about your salary—to the tune of 15–30 percent. So they actually thought they were giving us a healthy raise.

What this means is that even if you are an extremely honest person, you really have to lie…simply because that’s how the system works.

There’s another school of thought that suggests you don’t disclose your current salary, but simply ask to be paid what you’re worth, rather than what your current agency is underpaying you.

Of course, if a CD asks your current salary, and you point-blank refuse to say, he may get annoyed. A direct question does probably necessitate a direct answer. But that’s not to say it has to be an honest one. Ask yourself how much you deserve (honestly) and then add another 30 percent. If you do deserve it, you’ll probably get knocked down to somewhere near what you really wanted.

I think a lot of creatives don’t bargain hard enough because, aside from the fact that we’re not natural negotiators like account handlers or real estate agents, we worry that we’ll scare a CD away if we quote too high a figure. But actually, that won’t happen.

The creative director can always try to bargain you down. And yet it’s hard for you to bargain him up.

There was some excellent advice on how to negotiate your salary in the 2008 Global Planning Survey—they asked bosses for tips on what works. Here are the best ten:

1 Consider the total package. Think about where the job is going. The holiday allowance. The other benefits.

2 Get everything in writing.

3 Don’t come off as entitled and push too hard for big salaries when you are junior.

4 For your first job, take what you can get.

5 Sadly, you have to jump around to make more money.

7 Never tell your current salary. You deserve what your skills and talent pull in that market, not what looks better next to your old salary.

8 Negotiate hard. Creatives need to see a decent wage as a right rather than an indulgence. Realize that your hard and good work is making a profit for someone else.

9 Don’t keep going back and forth. The boss’s second offer is his best offer. After that he just gets pissed off.

10 Don’t be the first to suggest a number.

Final word—the bad agencies normally pay more than the good ones. They have to.

Think hard about what you need most at this stage of your career—great money, or great opportunities.

Is success due to talent, or working hard?

There’s a widespread belief that “a natural talent for it” is essential for success in creative fields—like art, music, and advertising—far more so than in less creative fields like banking, accountancy, or law.

But is there any truth to that?

In Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers he explains something he calls the “10,000 hour rule,” which states that to become expert at anything, one simply needs to put in 10,000 hours practising it.

The 10,000 figure comes from the research of Anders Ericsson, who in the early 1990s studied violinists at the Berlin Academy of Music.

“The curious thing about Ericsson’s study is that he and his colleagues couldn’t find any “naturals”—musicians who could float effortlessly to the top while practising a fraction of the time that their peers did,” writes Gladwell. “Nor could they find “grinds,” people who worked harder than everyone else and yet just didn’t have what it takes to break into the top ranks. Their research suggested that once you have enough ability to get into a top music school, the thing that distinguishes one performer from another is how hard he or she works. That’s it. What’s more, the people at the very top don’t just work much harder than everyone else. They work much, much harder.”

Some creatives cling to the belief that success is down to luck—getting the right brief at the right time, from a client that just happened to be looking for great work.

But if that is your view, you’ll be in a minority. The pop culture quote: “The harder I work, the luckier I get,” attributed variously to movie mogul Sam Goldwyn and golfer Gary Player, has by now gained general acceptance.

So even if you personally disagree with Gladwell’s theory that success is primarily due to hard work, you should certainly be aware that most people agree with it.

Which means that when you start a new job, it’s vital you establish a reputation as a hard worker—arrive before your boss arrives, and don’t leave until after he leaves. There’s an old saying that goes: “The man who has a reputation as an early riser, can get up at whatever time he chooses.”

If you are naturally a hard worker, my advice is don’t work hard gratuitously. Take your full holiday entitlement, and take your weekends—unless there’s a screaming emergency—else you’ll either burn out, fall out of love with the business, or end up depriving yourself of essential external stimulation, and your work will suffer. It’s easy to get into the habit of always leaving the office late as a matter of course. Don’t do that. Keep an extra gear in reserve, so you can kick up your work-rate when there’s a major crisis, or a major opportunity.

FOLLOW THE PREVAILING CULTURE

The question of how hard you should work is partly answered by the prevailing culture of the agency you’re working at.

In some agencies, everyone works hard. “If you don’t come in on Saturday, then don’t bother coming in on Sunday”—words supposedly said by Tim Delaney, co-founder of UK hotshop Leagas Delaney. Wieden & Kennedy has such a reputation for long hours that it has acquired the nickname “Weekend & Kennedy.” If you don’t work hard in an agency like this, you’ll have a double problem—not only will you not produce as much work as everyone else, but also, you won’t fit in.

There are plenty of agencies where creatives generally work normal office hours. If that feels like what you want to do—perhaps you have a family or other interests, you’re just not that into advertising, or you’re mentally exhausted by six o’clock—then you’ll be a lot happier if you work at one of these places.

But be aware that even at the “normal hours” shops, there are still plenty of times when you will have to work abnormal hours. Nearly every account goes into crisis from time to time, requiring late-night working for the early-morning meeting. And pitches eat weekends.

It must also be said that advertising is a job that can prey on your mind outside office hours. When I’m working on a brief, it gives me a kind of psychological eczema that I find myself scratching in the shower, on the bus, and on the toilet.

If you’re looking for a 9 to 5 job, this probably isn’t it.

People are normally tempted to move for one of three reasons: more money, more opportunity, or they just fancy a change.

MORE MONEY

All of these reasons are valid. But one of them—the finance factor—is almost never mentioned. In every interview you’ll ever read in an advertising trade magazine, a creative-on-the-move will talk about the “exciting new challenge” he’s been offered.

He’ll never say “Look, the money was just amazing. Like, I mean really amazing.”

Nevertheless, money is a motivator. Of course it is. We all have bills to pay, and as creatives get older, some have ex-wives and school fees to pay. And for a young creative, the difference of just a few thousand pounds a year can mean the difference between a clean apartment in a safe part of town, and a hole with forms of insect life not yet known to science. So I don’t devalue the importance of money as a motivation. And I always advise people that if you can get a job at an agency as good as your current one, but for more money, then take it.

It’s the job of a boss to pay you as little as possible. That’s just how capitalism works—if they paid everyone what they were worth, there would be no profit margin. You will be at your best-paid when you move jobs, because that is when you get your market value. Then, gradually, your pay starts to fall behind again. So if income is important to you, you need to move regularly to maximize it. And the best time to maximize is when you have just won an award or two. That is when your market value will be at its peak.

One thing to bear in mind though—every time you make a move, you’re taking a risk. However well you know an agency from the outside, there will always be things that surprise you when you get on the inside. They may not be things that you like. However well you get on with the ECD at your interview, he might not be the same when you’re working there. He might be better. But he might be worse. You just don’t know for sure. Similarly, you can never be certain that your style of work will be right for the agency, or that you’ll fit in there.

So make sure the additional income they are offering is enough to discount this “risk factor.”

The question of whether to take more money to work at a less good agency…is a difficult one. The answer depends on how your career is going.

If you’re still on the way up, you probably should not take the money. The reason for this is that, even if money was your sole motivation (which I’m sure it isn’t), you wouldn’t be maximizing your income over your whole career if you did that. You would get a short-term gain, but may lose out in the longer term, by denying yourself the opportunity to do the truly great work that could send your income soaring.

“Never make a decision based on coin,” is how Fallon legend, Bob Barrie puts it. “Do brilliant work and you’ll be rewarded more in the end anyway.”

However, if you’re on the way down, either because you’ve lost the magic, drink too much, prefer to spend time with your family rather than in the office—or whatever the reason may be—then it may be the right thing to take the money. Senior creatives talk (in private) about “cashing in.” After eight, ten, or 15 years of busting a gut to create excellent advertising at the best agencies around, there comes a time when you may want to take your foot off the gas, work at a slightly less good agency where there’s less pressure creatively, and where you can command a large salary. Nothing wrong with that. There’s more to your life than your career.

The second reason for moving—more opportunity—is more straightforward. If you can get a similar job at a better agency, you should. It’s probably not worth moving to an agency that’s only a little bit better (remember, there’s the risk factor I mentioned earlier to consider), but if you can go up to a new level, you should do so. Don’t let fear hold you back. If you’re good enough to get a job there, you’re good enough to do well there.

Some people wonder whether it’s worth taking a pay cut for a job at a better agency. It is. The likelihood is that the short-term salary drop is soon overtaken by the greater rewards that come from doing better work.

The only caveat about moving to a better agency: establish exactly what you’d be working on. Even the best agencies have their less glamorous accounts, and if the job involves working exclusively on one of those, then perhaps it’s not the opportunity you imagined. On the other hand, there is a school of thought that says that once you are in, you’re in. There are plenty of people hired to do the “bread-and-butter” stuff who have gone on to produce work on the agency’s showpiece accounts. Just make sure you know what you’re getting into.

Another opportunity it may be worth moving for is the chance to creative direct. Some (not all) agencies find it hard to promote rank-and-file creatives to CD. They know their own creatives very well, so maybe aren’t as excited by them as they are by a creative from another agency, who they don’t know, so who might be somehow special, and thus more suitable to be a CD. So just as in all walks of life, sometimes you have to move to get a promotion.

LACK OF OPPORTUNITY

Sometimes lack of opportunity is a reason to move. If things aren’t going well at your current agency—you haven’t had much work out in a while, you’re not getting the good briefs, or you don’t think your ECD rates you—then you should have a look around and see if any better opportunities are out there.

FANCY A CHANGE?

Sometimes people move just because they fancy a change. It may be that you want to change cities, or even countries; one of the great things about our job is that you can do it anywhere. I have a friend who began his career in Sydney, and has since worked in Amsterdam, New York, London, and Los Angeles. And you don’t necessarily need language skills to work abroad. If you speak English you can obviously work in countries such as the US, UK, Australia, South Africa, and New Zealand, but English is also near-universally spoken in the advertising industries of China, India, Singapore, and Holland. And if English is not your first language, that may not even matter, as long as your English is at least pretty good (copywriter) or passable (art director). It by no means needs to be perfect.

However, it’s not necessary to move countries to have a change. Sometimes people just get bored of the accounts they’re working on. This is especially true in agencies where creatives are assigned to specific accounts (common in the US). Even if you’re working across every account in the building, you may find you see the same briefs come round again and again. You may want a change of scenery, to meet some different people, or just experience a different way of working.

There are no rules about the number of years you should stay at one agency. If you feel stale, move. On the other hand, if you’re happy to come into work every day where you are, then don’t shake things up.

The best way to move is via a headhunter.

As your career advances, it becomes more and more important to get to know the headhunters in your market. If you find one that you like, and trust, you can get excellent career advice from them. They will call you from time to time to discuss job opportunities. Tell them honestly what city you want to work in, what type of agency you want to work at, what type of accounts you would like to work on. The more you tell them, the more they can help you.

Make sure you have your salary story straight before you speak to a headhunter for the first time.

They will be keen to establish what you are earning and what your expectations are, because that will help them determine the jobs you are suitable for.

A lot of creatives—because we’re creative people not business people—don’t feel comfortable with negotiation. The good news is that your headhunter will do the negotiating for you.

Headhunters may also ring you up and tell you that such-and-such a creative director is keen to meet you. If it’s an interesting agency, meet them, even if you don’t want to move right now. It’s good to stick your nose out from time to time. If you don’t like what you see, that’s a good thing, because you’ll be happier where you are. If you do like what you see, then it’s a good thing, because now you have options.

THE INEXPLICABLE CURSE

Final word on this subject. After you move, be prepared for one of two things to happen. Occasionally a new team hits the ground running, cracks every brief in sight, and makes great ads right off the bat. But more often, there’s an inexplicable curse, and it can take a new team up to a year to get an ad out. No one knows why this is. Maybe it’s getting used to a new way of working, or a new culture. Whatever the reason, be aware of it—creative directors are, and they do make some allowances. So don’t let that fear hold you back. If your reasons for moving are valid, move.

WORKING FREELANCE

Most creatives first start freelancing when they get fired from their permanent job, and don’t want to go straight into another one. Others start out their careers freelancing, before settling into a permanent position later.

But to give you an overview, I’ll set out some of the pros and cons of the freelance lifestyle here, and also Ten Tips on how to make it work.

PROS

The main plus is obvious: you can work when you want to (usually in the offices of the agency employing you but, in some cases, from home) and when you don’t want to work, you don’t have to.

This means you can take as many holidays as you want (albeit unpaid) and you’re not limited to the two-weeks-at-a-time maximum that permanent employers impose. Many creatives combine freelance work with traveling, or take regular breaks to pursue personal projects.

“I’ve enjoyed having time to do other things, like writing novels and short films,” says London freelancer Lorelei Mathias. “And being freelance gives you a chance to play the field a bit before settling down in the perfect job.”

“Freelance definitely broadens your outlook,” agrees experienced UK freelancer Nathalie Turton. “You get to see how different agencies all do things so differently. Through my years of freelance I have been offered permanent jobs but I haven’t wanted to give up freelancing.”

“You’re always on your toes,” she adds, “which keeps things exciting. Every week/month it’s a different journey to work, a different office, different people, different briefs.”

For many, a further attraction is that you’re not involved in agency politics, and not required to take on much responsibility.

Most of all, when you’re working, the money is excellent (freelancers are paid a much higher daily rate than regular staff, to compensate them for the short-term nature of the contract).

And you may occasionally get a job where you’re brought in for an emergency…then no one briefs you for a month, so you’re getting money for nothing. As well as being able to earn a higher income, you actually pay a lot less tax, because freelancers are allowed to offset a whole slew of expenses.

“Assuming that you are temperamentally suited and have a decent work ethic, freelancing can be a great way to go,” says Jim Morris, a US freelancer who goes by the brand-name “The Communicaterer.” “But you won’t know for sure unless you give it a try. Some people thrive on the autonomy, flexibility, and liberating work-lifestyle that freelancing can offer. Others are so uncomfortable with not knowing when the next assignment will come that they become chronically anxious.”

CONS

Insecurity. As soon as you get one job, you have to organize the next one. You’re constantly on the lookout for work.

And aside from the challenges of the lifestyle that you’ll have to come to terms with in your mind, there may be challenges to face in terms of how you’re treated in your agency.

Some places will look after you well, setting you up with IT the day you arrive, and giving you good assignments. Perhaps their attitude is they’re paying you twice as much as the permanent staffers, so they might as well get their money’s worth.

But in some agencies you’ll get treated like a dog—the worst briefs, and account handlers and planners constantly rewriting your work because they don’t know you and have no incentive to build a relationship with you.

And while ostensibly you are paid quite well, actually getting the money can be a problem. There seems to be a perception in some agencies that freelancers do not need to eat, pay their mortgages or buy pants, thus no need to pay their invoice.

Some freelancers report that they don’t actually give you money until you threaten to firebomb the finance department. And even then they don’t pay you; they just don the asbestos suits they keep under their desks. Plus, they automatically lose your first invoice.

The social side of being a freelancer can be less fulfilling than being on-staff. Freelancers are like novice fighter pilots, i.e. there is a perception that you’re not going to be around for long, so in some agencies people don’t bother getting to know you...or even acknowledge you in the corridor.

“You feel like the New Person all the time, and that can be draining,” says Lorelei Mathias. “You don’t know what to talk about when you bump into strangers in the lift.”

There often isn’t enough help too. It is assumed that freelancers are unlike normal people and will automatically know where the printer is. Even then, it may take IT three days to attach you to that printer. Perhaps they assume that freelancers are unlike everyone else and don’t need to print anything.

(Bringing in your own laptop may help, though it may be impossible to get it to attach to the agency’s network. Even though three IT guys are at your desk staring at it and saying “server” a lot. They will, however, admire it because, for tax reasons, you will have bought a really nice one.)

“We once worked at an agency for a whole month without access to a printer or the internet,” reports one freelancer, who prefers to remain anonymous. “Luckily I had my own laptop, otherwise I wouldn’t have had a computer either. And every Friday they’d all go to the pub and ‘forget’ to invite us. It was like being bullied at school.”

The briefs you will be given are often the most difficult ones in the agency. They will have been attempted, multiple times, over an entire year, by every creative/planner/desperate account man in the building, and remain resolutely uncracked. The creative director will have given up on them and you will be reviewing with the head of planning, who by this stage has been driven quite mad by the project. You will be informed that the client will leave the agency if you don’t crack the brief in the next three days.

(This is understandable in a way. The role of a freelancer is to pick up the slack, work that’s going spare, and the really great briefs are rarely going spare.)

You may find that when you turn up for work on your first day, the person who got you in will have carefully omitted to tell anyone about your impending arrival. He will also be out at a meeting all morning so that you will have lost an entire half-day of the three you have been allotted to crack this uncrackable brief.

No one will tell you about the security system and you will get trapped in a stairwell. For some reason people assume freelancers are different from normal people and they have already received their security passes by magic or something.

For some, it’s frustrating that you rarely get to see any projects through to fruition. That means no shoots, no nice lunches while in edits, and little produced work for your book.

“As great as freelancing is, you need to be permanent somewhere in order to get work out, and move up the career ladder,” advises Nathalie Turton. “As a freelancer you kind of move horizontally.”

The bottom line is that if you have a really good book...you will be in high demand, get a lot of money, and good briefs. The second tier of freelancers might also make decent money—but won’t get briefs good enough to improve their book.

The better your book, the better your freelance gig. Moral: if you fancy the freelance life, delay starting until you have some really good work in your book. Then you can live that life well.

TEN TIPS FOR SUCCESSFUL FREELANCING

“Freelancers, especially early on, tend to price their services timidly, insecurely,” reckons Jim Morris. “They don’t know their market value and are afraid of being shut out of a project by overpricing themselves. Learn what the hourly rate and day rate range is for lightweights through heavyweights in your field. If you come in a little high, the client will usually let you know, giving you an opportunity to reduce your rate or fee. These matters are usually negotiable, so negotiate.”

Sh*t-canned. Made redundant. Laid off. The sack. Given your cards. Given your marching orders. Kicked out.

Like anything naughty, dirty, or embarrassing—think of booze, cash, and boobs—getting the boot has many synonyms.

No statistics specific to our industry are available, but anecdotal evidence suggests that you are almost certain to be fired at some point. Ours is a notoriously insecure business.

But some argue that getting fired from time to time is actually healthy.

Kash Sree, the talented UK-born creative behind Nike “Tag,” has said in interviews that “if you’re not doing at least one thing every year that could get you fired, you’re not pushing hard enough.”

So when is it most likely to happen? You’re probably in most danger at the beginning of your career, before you’re established. The middle bit is tricky too, when you’re earning a reasonable salary but don’t yet have a huge reputation. And senior creatives certainly aren’t immune. Some get to a point where they think they can’t be fired, because they’re integral to some large account or other. However, the relationship with the creatives is never as important to clients as the relationship with the suits. And the life expectancy of the creative director himself is notoriously short, as he’s the easiest person to blame when the agency’s work (like 99 percent of all ad agencies) falls short of the industry’s Top 1 percent.

Occasionally, being fired can be a positive. I know of one team that had decided to leave their agency, and they got another job, but before they could resign, the ECD dropped by to say he was letting them go. They started work at their new agency on Monday, with three months’ money in their pockets.

But usually it isn’t.

BLAME

I have been fired twice in my career.

The first time it happened, I was working at Saatchi & Saatchi in London when Maurice and his brother Charles quit the agency to set up their own firm—M&C Saatchi. They took about one-third of the clients with them. Obviously, redundancies had to be made. I was working on my own, because I had recently split up with my art director. I had also fallen out with my boss (long story). I was a junior creative—only two years’ experience—and while I had produced a few ads here and there, I hadn’t done anything particularly brilliant. So in a nutshell, given that they had to get rid of about 15 creatives, I could hardly blame them for getting rid of me, and I could hardly blame myself either. Could I?

The second time, I was working at a really bad small agency, when the two founding partners decided to separate, the company was broken up, and there was no job any more for my partner and me. Once again, I told myself it was not my fault.

Getting fired is a traumatic experience that can badly dent your confidence. It was several years before I could walk down Charlotte Street, past the Saatchi’s building, because it was too upsetting and I was afraid I might run into someone I knew.

And it’s that trauma, I believe, that leads people to construct elaborate theories as to how undeserving and unlucky they were to get fired, how blameless. It’s a sensible strategy. The last thing your ego needs in times of crisis is to start questioning itself. That’s why most people who are fired get mad at their boss. And they get mad at the company—after all, it’s a ridiculous agency, which started going downhill years ago.

It took me years to realize that the person responsible for my firings was me.

In the Saatchi’s case, it’s true that they would never have had to make redundancies if the M&C split hadn’t happened. And I was a singleton. But the fact is, they chose to fire me, and keep others.

In the case of the small agency, it was even more clear-cut. This shop split into two even tinier agencies, neither of which wanted me (or my partner). The only other creative working there at the time did get taken on by one of the new units…but I didn’t.

So at the risk of sounding like one of those self-help books with titles like “He’s Just Not That Into You” or “Yes You Do Have A Fat Bum”…what I’m saying is that if you do get fired, it is your fault.

In letting people go, an agency will always choose the people it thinks are least good value for money, the least talented, the least fun to have around, the least suited to the agency’s culture, and the most easily replaceable.

The first of these, in this advanced stage of capitalism that we inhabit, is by far the most important. The quality of work you produce relative to the dollars that you cost—that’s the most important thing they look at.

The reason I’m being so brutal is that I believe the sooner you can figure out where you’ve gone wrong, the sooner you can start to put things right.

Yes, by all means go through a phase of blaming your boss, your partner, or the idiot clients who failed to buy your best ideas. But after that, you must enter a period of introspection.

ARE YOU HAPPY WITH YOUR WORK?

The best piece of advice I was given when I got fired was by Richard Myers, former European creative director at Saatchi’s. He said to me: “Are you happy with the work you have in your book? That’s the only thing that matters.”

I took a look at my book and realized I wasn’t happy with my work. It was OK, but it wasn’t the best I could do. Truth was, I had been having an enormous amount of fun in my first job—too much, really, like coming in to work at 11am and playing football in the corridor—but I hadn’t done great work. The decision I made was to take my job more seriously and, while still having fun, not goof around quite so much.

If you were already doing the best work you can—and it seems that wasn’t good enough—or you have commitments that prevent you putting more time and effort in, or you just don’t want to put that much time and effort into a job, then you can simply drop down a notch or two in the food chain for your next position—that’s a perfectly valid call to make too.

QUESTIONS TO ASK YOURSELF

Are you with the right partner? Were you working hard enough? Were you working smart enough? Were you too feisty, or too compliant? Were you working somewhere you didn’t fit in? Had you taken on too much responsibility or, conversely, not enough? Were you working somewhere they don’t like the type of work you do? Would you be better suited to a specialist agency of some kind? If you were working above-the-line, would you be better suited to a job below-the-line, or vice versa? Were you in the right city, the right country? Was there something in your home life or your personal life that stopped you from succeeding?

Figure out what the problem was, and fix it.