Focus on conversations

Conversations are the most intimate use of speech. We are engaged in them continually from our earliest days to our final hours. You use them for idle chatter or with a clear purpose. You converse in person and on the phone. Your conversations are easy or complicated, conveying everything from shopping lists to love, and from good news to breakdowns.

Because of their familiarity, we think we understand them. So why is it that, so often, people don’t hear what you say – or they hear it in a way that really surprises you? Let’s find out.

The art of conversation

Conversations are intimate. So, to make them as effective as possible, focus on the ‘you’ in communication. When you put the word ‘you’ into your conversation, you alert the other person that they need to listen, you prepare them to take responsibility for how they respond, and you make them feel at the heart of your concerns.

The you principle goes further. When holding a conversation, people’s favourite topic is usually themselves. So when you can focus the conversation around my interests and around me, I am likely to consider you a good conversationalist. Take an interest in me, listen carefully and refrain from judging me.

Start a new conversation on safe ground by asking about something safe, such as impressions or facts. Feelings and emotions, on the other hand, may be too intimate a subject, and might scare me off. When you go somewhere where you are likely to need to start conversations, especially with people you don’t know, it pays to have a stock of conversation starters and some familiarity with current events.

Speaker’s checklist: conversation starters

Most conversation starters are on a spectrum from situational to personal. Since the ‘you principle’ tells us that you should focus on the other person, rather than on yourself, that means me.

- Make an observation about where we are: “There is a good turn-out today, for a mid-week event.’

- Ask me something about where we are or some specific feature of it: “Do you know anything about the history of this building? It’s so impressive.’

- Ask me about how I came here: “This place is nice and central; how did you come here tonight?’

- Ask me what drew me to come here:’ ‘What appealed to you most about this event?’

- Express an interest in speaking with me:’ ‘I couldn’t help noticing you and wondered if you would mind if I introduce myself?’

- Make an observation about me (avoiding anything that might embarrass me): ‘’I am interested in what you said earlier on. Your comments were thought-provoking.’

- Ask me something about what I am wearing or have with me: ‘’I see you are carrying Mike’s new book – what are your impressions of it?’

- Ask me something you think I might know about: ‘’When you are writing a book, do you have a process you follow?’

- Ask me something about myself: ‘’What interests you most about the work you do?’

When you want to ask me a question about myself, the best ones open up a whole realm of new information beyond the scope of the question itself. ‘If you could travel to one place in the world, where would you most want to go to?’ will open up a conversation about the place, the interests that attract me there, our past experiences of travel and my attitudes to all sorts of things from culture to food to transport.

I suggest you avoid those ‘clever’ questions, which make people feel they need a ‘clever’ answer, until you are both comfortable with one another: ‘What would be the one statement that summarises your philosophy on life?’ might simply elicit: ‘Don’t ask questions that make people feel inadequate.’

Conversational genius, Leil Lowndes, gives excellent advice, noting that ‘So, what do you do?’ is another question that can cause embarrassment – as well as marking you out as potentially a relentless networker or shamelessly looking for opportunities. Far better, she advises, to ask: ‘How do you spend most of your time?’ Her book How to Talk to Anyone is a conversationalist’s goldmine.

Once you get started, carrying on a conversation becomes easy. If you find yourself stalling, you can either restart with another conversation starter, or, better, pick up on something I said earlier on and either comment on it, or ask me about it. There are four basic conversational skills that keep a conversation going along nicely:

- Rapport with your conversation partner.

- Appropriate eye-contact.

- Serious listening.

- Being comfortable with pauses and silence.

If your conversation is going well, it can be hard to end it. The best ways are always to express your pleasure in the conversation and politely but confidently excuse yourself. You really don’t have to apologise for having other concerns in your life. ‘It has been a pleasure speaking with you. Now, I need to get home/prepare for my talk/get some food/find someone …’

If you are interrupted, on the other hand, perhaps by a phone, then you should apologise for that: ‘I am really sorry: I have enjoyed speaking with you and I wish I didn’t have to take this call. Unfortunately, I must.’ Notice here, how I have avoided the ‘but’: ‘I have enjoyed talking, but I must go’ weakens the first part significantly.

Now let’s examine the four basic conversational skills in some more depth.

Rapport

Rapport is the dance we create, carrying the parts of a conversation from you to me and back, constantly building our relationship and empathising with one another’s perceptions. Rapport connects us, helps us to understand each other and creates a sense of trust. Anything that you can do to strengthen rapport can also help people to listen to you.

Rapport is based on similarity, so to strengthen rapport, you need to find and emphasise those points of similarity between you and the people who are listening, whether it is one conversation partner or an audience of hundreds. Remember:

‘People like people who are like themselves.’

Very simple outward cues can help at the outset. Dressing in a way that conforms to people’s expectations, for example, or an opening statement that begins: ‘Like you, I …’

Agreeing with and building upon things the other person says will increase your rapport, but what do you do when you disagree? The secret is to be honest in a way that keeps rapport: ‘I can grasp what you mean, so let me see how you feel about this interpretation.’ Or how about: ‘I’d like to understand better how you made that assessment: can you say more about the difference between …?’

Speaker’s toolkit: building rapport

Your toolkit for rapport building is … you.

Body position

In conversation, the orientation of your body to mine (turn to face me for greatest impact) and its proximity can make or break rapport. If I don’t look comfortable facing you directly, then allow yourself to stand slightly to one side too. Get the distance wrong and I will either feel you are too close and familiar or too distant and cold. Luckily, we all have a fairly well-tuned sense of the bubble around us – at about arm’s length.

I referred a little while ago to Leil Lowndes. Of all her tips, my favourite is ‘The big-baby pivot’. When someone comes towards you, don’t just look at them and don’t just turn your head, but swing your whole body round to greet them and give them a powerful smile that says ‘Thank you for coming over to me; I am looking forward to speaking with you’.

Posture, gesture and expression

Watch two people deep in conversation at a coffee shop or bar. You will see matching postures, gestures that look the same (made almost simultaneously) and similar expressions passing over each person’s face. We do this naturally when we are in rapport. When we do it deliberately, picking one or two aspects at first, we strengthen rapport.

Vocal patterns

All the normal patterns of how we speak can be shared. When you match the volume, pace and tone of your speaking to mine, you will increase our rapport and make it more comfortable for me to listen to you. The one aspect to avoid is accent: since very few of us have a precise enough sense of accent, attempting to mimic it comes across as disrespectful – even mocking.

Word choice

Notice some of the words I use a lot and pepper them occasionally into your speech. This will make me feel at home with your turns of phrase. They will feel comfortingly familiar to me. A common example is the words we use to describe how we understand one another. Some people see what you are saying and understand your point of view (my own favourite), while others hear you clearly, so that your words ring true. Some get a feel for your angle on things and grasp your meaning, while others like to sniff out the essence of your argument to see if it smells sweet or if it stinks. If you can use the same senses in your speech – visual, auditory, bodily or smell – then the other person will see, hear, grasp or sniff out your message quickly.

The not-so-royal ‘we’

Of all the pronouns, ‘we’, ‘us’, ‘our’ and ‘ours’ are the ones that confer intimacy. Use them to build rapport when we are talking so that we can feel like our friendship is starting to develop and we can readily agree if someone challenges us.

From the laboratory: mirror neurons, empathy and rapport

In the late 1980s and the 1990s, scientists at the University of Parma in Italy gave us a new and controversial insight into the workings of our brains. We had known for a long time that when we move, motor command neurons fire in our brain. And when we are touched, neurons fire in the somatosensory cortex of our brain. What Giacomo Rizzolatti and his colleagues discovered is that a smaller number of neurons also fire when we see someone else move, and also when we see someone else being touched.*

This means that when I see you in a particular posture, making a specific gesture, or adopting an expression, it causes motor neurons to fire in my brain. I get a sense of how it feels to be doing what you are doing: I get a sense of what it is like to be you.

While the interpretation of what these so-called ‘mirror neurons’ mean and how they work is still being actively researched and hotly debated by neuroscientists and psychologists, it is clear that there is a neurological basis for rapport and empathy. It is as if the barriers between us are less when we observe one another closely and when we adopt similar movements.

Eye-contact

Eye-contact is a critical part of the body language, which makes or breaks rapport between people. As a speaker, you need to be aware that some people will listen to you most comfortably when they are holding eye-contact with you; while other feel most at ease by looking away. So there is no ‘right’ amount of eye-contact: there is just what is right for the person you are speaking with. Use your ability to sense when other people become uncomfortable to tune the frequency and depth of your eye-contact, so they feel completely at ease. Break contact as soon as you detect any awkwardness. Go back to Chapter 4 (page 47) if you want to remind yourself how to know the right moment to break eye-contact.

Serious listening

Perhaps the deepest need we all feel is for someone to understand us and honour our emotions, by listening to us and acknowledging how we feel. The problem is that, for something most of us do every day, listening is something a lot of us are not very good at.

We listen at four distinct levels:

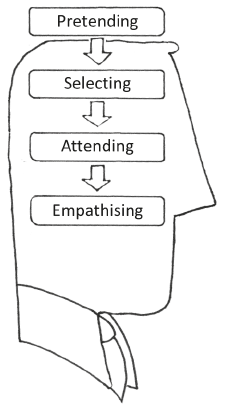

LISTENING LEVELS

Pretending

The shallowest level of listening is merely pretending. There is a superficial awareness of the speaking going on, which has only the most cursory effect on us. This is hardly listening at all; it is not respectful, and will probably be recognised for what it is by the other person.

Selecting

The human brain is able to listen in part to two conversations at once, and we frequently do: selecting which to pay more attention to and which to scan for important cues. All I pick up is some minor elements of what you are saying, so that if there is something important, I can swap attention to you. The commonest alternative voice, if it is not the conversation on the other side of the room or the TV in the corner, is the voice in my own head.

From the laboratory: dichotic listening

The cocktail party effect is our ability to select one conversation from many going on in the same room. Donald Broadbent and Colin Cherry studied this by feeding different information into each ear. They called it dichotic listening. They found that we can select which channel we wish to focus on, and can also swap channel if personally significant information appears in the neglected channel. This is akin to listening to the radio while your relative talks to you on the phone. As soon as they mention something important, you switch your attention from the radio to the telephone.

Attending

Fully attentive listening allows me to hear all your words and for them to affect my thoughts and interpretations. As I fully engage with your interpretation of reality, it may also start to affect my feelings. Active listening, where you participate fully and perhaps even make notes, is at this level.

Empathising

Now I am at the deepest level of listening of all, open to your emotions and allowing them to affect me. Consequently, my feelings and even my sense of reality may change through listening to you, and I can sense your needs and feelings as a result.

The question that arises is how can you listen at the attending and empathising levels?

How to listen

While much of listening is automatic, the following ten steps can turn it into a conscious activity that you can practice and perfect. Each step overcomes one of the barriers to good listening.

Step 1: Become curious

A sense of curiosity helps you overcome the barrier of your certainty about the world. Ask a question that truly interests you.

Step 2: Engage

Face me, make eye-contact, and remove all distractions. If you have a laptop open, close it – even when you are on the phone. This helps you to overcome the barrier of separateness and allows your mirror neurons to dissolve the emotional boundary between us.

Step 3: Put yourself out of the way

You have opinions, ideas, beliefs, values and prejudices. These create a barrier to hearing what I say by filtering my words through your reality. If you can mentally set these aside and resist the temptation to judge me, you will be better able to understand me instead.

Step 4: Silence your inner voice

Your inner voice, or self-talk, is a barrier to listening. While you are listening to yourself, you are not concentrating on me. Turn it off and give yourself permission to respond when it’s your turn.

Step 5: … and still your body

Movement is a distraction to my speaking and your listening. Remove it by becoming still, curbing your fidgeting and halting your doodling.

Step 6: Become aware of your listening

The next barrier to listening is that your brain can work faster than I can speak (four times as fast, it is often reported). So, your mind will wander unless you give it something constructive to do. Become aware of the quality of your listening, and:

- notice key words and phrases that I use;

- spot what I emphasise and what I avoid;

- notice conflicts between my words, tone of voice, expression and body language;

- pay attention to all channels of my body language: gesture, posture and voice;

- listen between the lines … to what is not said, as well as what is.

Step 7: Let me know you are listening

Use nods, smiles, the echoing of gestures and simple phrases and sounds such as ‘I see’ and ‘uh-huh’ to keep me confident that you are still engaged.

Step 8: When I stop – think

Allow yourself time to think before you respond. We will return to silence later, but this is about the ‘need to respond quickly’ barrier that puts pressure on you to answer before you fully process what I have said. If I have said something important, I don’t want a quick response: I want a considered, respectful response.

Step 9: Repeat, rephrase and summarise

Repeat the essence of what I said, using some of the same key words and phrases you heard at step 6. This will emphasise to me that you were listening and that you ‘got it’ – even if you didn’t. If you need to clarify, only after repeating my own words should you test your own interpretations by rephrasing: ‘When you said you feel “helpless”, do you mean you don’t know what to do next?’ ‘No,’ I might reply, ‘I mean that I know what to do, but I also know it may have no effect at all.’ When you are sure you understand me, you may want to summarise what I have said.

Step 10: Go to the edge

If I am not confident enough to speak about what really matters, you may need to take me to the edge, to make it easier for me to take the leap. Do this by carefully speculating about what I may be feeling. Invite me to assess your interpretation – which is easier than starting from nothing.

From the laboratory: listening can really make a difference

In a 2012 study by Daniel Ames and colleagues Lily Maissen and Joel Brockner, workers rated colleagues on measures of listening skills, verbal skills and influence.* While speaking skills had a significant effect on ratings of influence (63 per cent correlation), which we would expect, listening skills had an effect on its own that was almost as large (54 per cent correlation).

They also found that, for people with good verbal expressiveness, good listening skills had a particularly profound impact on enhancing influence. The researchers suggest this is because listening builds trust. Being good at listening will make you more influential – whether you are good at speaking or not. If you are, its effect is profound.

Silence

‘In the silence is the truth.’

Silence is a magic part of conversation. Most people feel a little uncomfortable with silence. So if you can master it and feel comfortable in its presence, you can increase your authority and control the flow of the conversation more effectively.

Silence after I speak

When I finish speaking, if you can remain silent for three seconds you will indicate that you need to think about what I said. That tells me you respect it and signals that I have said something important. Jumping in with a quick response belittles what I have said by telling me you don’t need to think about it to respond: my point was obvious and your answer was easy.

And if you give me a silence, I may just try and fill it myself. Since I have said what was easiest to say, the next things I speak may be deeper, more personal and more revealing. You can learn a lot when your next question is silence.

Silence after you speak

When you have finished saying what you intended to say, what do you do? Do you stop? That is what you should do.

Too often, we feel the need to add something else, to qualify what we have said, or to check ‘Was that okay?’ When you do that, you are diminishing the power of what you said. It becomes less authoritative and robs me of the chance to really evaluate it.

The bonus that silences offer a speaker is that they slow you down and increase the sense of gravitas and charisma that you broadcast. If you want to speak so people listen, make silence your friend.

Telephone conversations

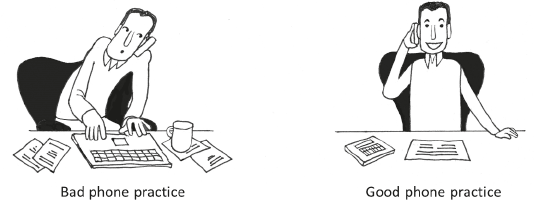

Follow the same advice for a telephone conversation as you would face-to-face. Here are some of my top tips for applying it.

Speaker’s checklist: tips for a telephone conversation

Before making a call

- Plan your call. What is your desired outcome? How will you open the conversation? What will you do if you go through to an answerphone?

- Keep a notebook by your phone. Start each call by writing the date and the name of who you are calling, ready to take notes.

- Turn off your computer or move away from it.

- As you dial, clear your throat. As it is ringing, smile.

Picking up a call

- As the phone rings, stop what you are doing and clear your throat.

- Then answer the incoming call promptly, smiling as you pick up the receiver.

- Offer a cheerful welcome, then identify yourself clearly.

- If you know the caller, tell them you are glad they called.

- Move any food or drink out of reach, to avoid temptation.

- Keep a notebook and pens by your phone. As soon as you know who is calling, write the date and the name of who it is, ready to take notes.

During the call

- If you called, start by checking it is a good time to call and how much time the other person has available.

- Speak slowly and clearly. Be enthusiastic and friendly. Make use of pauses.

- Use the caller’s name.

- Consider standing up. It will give you more energy and enable you to be more focused with your time.

- If you sit, sit upright. It will improve your concentration, your voice, and the subtle impression the other person will form.

- Listen hard – resist temptations to interrupt.

- Make notes.

- Offer to spell difficult words. If necessary, use A-alpha, B-bravo, C-charlie to ensure that the other person gets it right.

- Report back names, numbers and addresses, to check you have them correctly.

- Stay courteous and respectful … which includes not taking other calls!

Ending the call

- Summarise the conversation and any agreements.

- If appropriate, repeat your name, affiliation and contact details.

- Say goodbye as if you have enjoyed the call and look forward to the next one. Thank them for their time.

- Don’t be the first to hang up, unless you have both agreed that there is nothing more to say.

After the call

- Review and clarify your notes. Add anything that is missing.

- Carry out or schedule any follow-up tasks.

GOOD PHONE PRACTICE / BAD PHONE PRACTICE

Speaking with little purpose

Some conversations serve little or no purpose. They make neither party better informed, happier or wiser. They resolve nothing, generate no new ideas, make no progress and do nothing to improve your relationship. They don’t even make a pleasant pastime.

If you spot one of these unproductive conversations, the best thing you can do is back out of it gracefully and get on with something more useful and pleasant. Let us survey four typical examples, so you can recognise them.

Stifling conversations

Have you ever felt that someone was stifling you? Probably with good intent, but they were holding you back by being over-protective, over-caring and over-bearing. At best, they were protecting you from making your own mistakes; creating a sense of dependency upon them. At worst, they were patronising you; making you feel small and possibly even portraying you that way to others. Subtle though it is, this is the exercise of power by one person over another. It may not feel aggressive, but it is certainly not respectful.

Critical conversations

Some people just know what is right – without a doubt in their minds. Ironically, they often do not have the expertise that could justify such certainty. Instead, they are relying on half-remembered rules and yesterday’s experience. But criticising you makes them feel good. At the very best, such critical conversations drive compliance with one person’s expectations, denying others any responsibility. At worst, they may be based on outmoded thinking or be blind to the particular realities of the situation. They deny opportunities for finding creative alternatives. This is another way of exerting power and it too can create long-lasting resentment.

Petulant conversations

Stamping of feet and raging against injustice rarely do more than draw attention to the speaker. Arguing without evidence and taking a contrarian stance – often without taking responsibility to act – is mere petulance: an attempt to exert power without any authority. At best, petulant conversations strive for new ideas and new freedoms, but often to little or no effect. At worst, they create pointless dissension and conflict.

Submissive conversations

In some unproductive conversations, the goal is to avoid taking responsibility by compelling another person to accept it. The very best this could achieve is to satisfy a desire for safety, but this is often more illusory than real. More realistically, it destroys not just the respect that people have for you, but your own self-respect too.

Speaker’s checklist: ways to turn people off from listening to you

- Smothering and gently dominating.

- Criticising, telling and assertively dominating.

- Complaining, ranting and aggressively dominating.

- Shouting, yelling and screaming.

- Whispering, mumbling, using evasive language and avoiding eye-contact.

- Talking too much…

- … especially about one thing …

- … which is often yourself.

- Interrupting and trying to dominate the conversation.

- Moaning and whinging about things you are unprepared to act upon.

Speaking with real purpose

On the other hand, mature conversations have a real impact on the world. They create new thinking, share insights, develop plans and make decisions. They improve relationships, help us to develop, and make people feel good. Mature conversations are characterised by self-respect and mutual respect; respect for facts, evidence and reason; responsibility and willingness for accountability; and by genuine choice in how to respond.

In the last section of this chapter, we will look at three examples of speaking with real purpose:

- Motivation (not its unproductive cousin, manipulation).

- Praise (not its unproductive cousin, flattery).

- Feedback (not its unproductive cousin, criticism).

And in the next chapter, we will focus on some of the hardest conversations of all, complicated conversations, which will get more adversarial as we move through Chapter 8:

- Giving bad news.

- Relaying tough messages.

- Arguing.

- Handling breakdowns in relationships.

- Dealing with conflict.

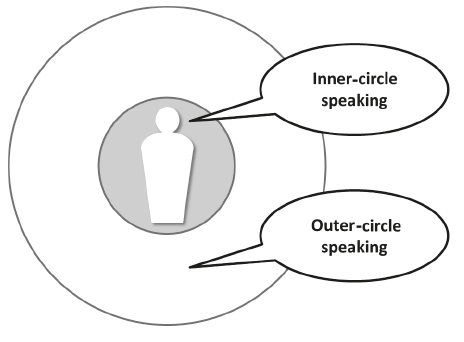

Before we look at some examples of speaking with real purpose, let’s start with a crucial concept. It will serve us well here and in the next chapter, when we look at complicated conversations. I call it inner-circle speaking.

Inner-circle conversations

How we communicate arises in part from having to balance a tension between two needs:

- Independence from other people.

- Involvement with other people.

As a result, we often find ourselves hiding our true message – what we truly observe, think and feel – behind a mask of social conventions. These protect us from what we fear: exposure of our true thoughts and feelings. Our need for independence partially obscures our message.

This is outer-circle speaking. Not only does it mislead listeners and fail to communicate the truth, but it also has a second effect: it undermines our credibility. This is because, superimposed on top of the message that we are putting out deliberately are a whole set of other messages that are leaking out of us, below our conscious awareness. These meta-messages communicate something of our true feelings, and the disparity between them and our deliberate outer-circle speaking.

People notice these differences in our gesture, posture, facial expressions, voice tone and pace, and shifts in pitch and volume, and even through our unconscious choices of words. Examples of this are when we make Freudian slips.

People aren’t interested in listening to the social conventions of speech: they want to listen to you – the real you: your passions, your feelings, your convictions. When your speech is not clouded by conflicting meta-messages that confuse people, people will listen hard. They will also believe you, because you will come across as confident and congruent.

As the Duke of Albany says in Shakespeare’s King Lear:

‘Speak what we feel, not what we ought to say.’

When you say what you are really thinking, and strip away the meta-messages to expose your true self, this is inner-circle speaking. This is the route to making complicated conversations successful, and engaging listeners one hundred per cent.

INNER AND OUTER-CIRCLE SPEAKING

When communicating information is paramount, a conversation can follow four rules, as set out by Paul Grice:*

- Say as much as you need to; no more.

- Be honest.

- Be relevant.

- Be clear.

Often, however, conversation has other, social, purposes. As a result, we must also add courtesy to Grice’s four rules.

From the laboratory: politeness and respect

Politeness and respect are not the same thing. Politeness is a set of meta-messages designed to balance our needs for independence and involvement. Robin Lakoff, a socio-linguist at Harvard University, set out three rules that we can follow, to achieve balance and be polite:

- Don’t impose on others: maintain a social distance to maintain independence.

- Offer options so the other person can make a choice.

- Be friendly, to increase involvement.

Politeness therefore gives us emotional payoffs by creating a defence around ourselves and by building rapport.*

Candour spectrum

Inner-circle speaking creates a challenge for us. We must balance a need for social politeness and all the benefits it confers with a desire for real candour. This creates a spectrum of possible responses between the extremes of being downright blunt and a fear of being honest:

- ‘I say it like it is’: If you are proud of your no-nonsense bluntness and you make no attempt to see other people’s perspectives, this does not recognise the inherent self-centredness of what you are saying.

- ‘No, no – no problem’: If you are afraid of being honest, you will confine all your speech to the outer circle. It reflects nothing of substance and fails to communicate anything you want to say.

True inner-circle speaking is able to respect both yourself and the other person. You are honest, you are open and you speak in a way that respects the other person’s integrity.

Motivation (not manipulation)

What motivates someone is as variable as people themselves, so there are many theories of motivation, each offering its own prescription. When you are able to have an inner-circle conversation with someone, you can gain insights into their deeper levels of understanding: their needs and deeper feelings. Here is where our values reside. This is the route to effective motivation.

If you can understand what is important to me, then you can relate what you want me to do to those values, and so motivate me effectively. What these needs are can vary from day to day and from one situation to another, so you also need to be sensitive to who I am today and not make assumptions that what is important to me now is the same as what would have motivated me yesterday.

Avoiding manipulation is a matter of steering clear of the three manipulator’s tricks:

Asking you to do something you won’t be able to do

If I set you up to fail with a task I know is beyond your capabilities, or if I know you won’t have the resources or cooperation you need, then any motivation I offer will be a deception.

Promising you a reward I won’t deliver

If I motivate you with a promise I cannot or will not deliver – and I know or suspect this in advance – then my promise is nothing but a lie.

Delivering a reward that you won’t value

I may make a promise and deliver, but if I know that the reward has less value to you than the effort you put in, then the bargain was not a fair one: I cheated you.

Praise (not flattery)

Offering sincere praise will not only make you feel good, it will increase your liking of me. So it is vital that I do not try to manipulate you with false flattery, just to win your favour. Most of us find giving sincere praise to be a challenge, so here are my three favourite techniques:

The little stroke

A simple, understated comment of appreciation, applied at the right moment, can remind someone that we value their contribution: ‘Nice work’ or ‘Well done’ or just ‘Thank you’.

The knee-jerk praise

When somebody does something especially good, allow yourself to show your feelings about it spontaneously. This works especially well in cultures where it is unusual to show how you feel: ‘Wow!’ or ‘Fantastic!’ or ‘I am really impressed’.

The particular favourite

When you look at something I have done and select one particular part to praise, I know that you must have reviewed all of it. Chances are you will pick the part I am proudest of, showing me how much care you have taken. And if you pick a part that surprises me, it can have even more impact: ‘I really like …’ or ‘This bit is excellent’ or ‘… impressed me the most’.

Feedback (not criticism)

Good feedback gives me information that will help me to assess what I have done, make changes if I choose and to perform better next time. Criticism, on the other hand, is all about telling me what you think – which may or may not be helpful as feedback. Three things make feedback particularly valuable:

What you observed

Make sure your feedback is based on behaviour that you have observed. Make it as specific as possible, to help me focus my response precisely, and give me examples and evidence that I can evaluate. Avoid personal comments about me, and concentrate on what I did and how it relates to what I was trying to achieve.

Why it matters

To motivate me, I need the ‘because’. So show me the impact of my actions and how that will change if I choose to make changes to how I behave in the future. Also put yourself on the line: why does it matter to you?

Shared responsibility

Feedback needs to be a shared responsibility between me – performing the action – and you – observing it. Therefore the process needs to be an open dialogue, with good-quality listening and questioning from both of us, to help me develop the best possible understanding of the impact of my choices.

The YES/NO of conversations

YES

- Remember the ‘you principle’ and focus your conversation on the person you are speaking with.

- If you want to speak so people listen, learn to listen well yourself …

- … and make silence your friend.

- Phone conversations matter – treat them with as much respect as a face-to-face conversation and learn the secrets of doing them well.

- Use politeness and social conventions to build rapport.

- Remember that inner-circle conversations communicate powerfully.

NO

- Don’t judge what I am saying while I am speaking – just listen.

- Don’t use ‘I say it like it is’ or ‘No, no – no problem’: both are disrespectful – the one of me and the other of yourself.

- Avoid manipulation, flattery and criticism.

- Remember that outer-circle conversations remain superficial.

- Steer clear of unproductive conversations of any sort – stifling, critical, petulant or submissive.

*G. di Pellegrino, L. Fadiga, L. Fogassi, V. Gallese and G. Rizzolatti, ‘Understanding Motor Events: A neurophysiological study’, Experimental Brain Research, 91, 1992.

*Daniel Ames, Lily Maissen and Joel Brockner, ‘The Role of Listening in Interpersonal Influence’, Journal of Research in Personality, 46, 2012.

*Grice’s conversational maxims were first published in 1967. They were reprinted in Syntax and Semantics, Vol. 3, edited by Peter Cole and Jerry Morgan (Academic Press, 1975).

*Robin Lakoff, ‘The Logic of Politeness, or Minding Your P’s and Q’s’, Papers from the Ninth Regional Meeting, Chicago Linguistic Society, 1973.