Focus on public speaking

It is a cliché that most of us would rather be the subject of a eulogy than the person giving it. It is not true, but it is true that few people have both a real talent for speaking to an audience and the confidence to do it. Yet those who do appear to have a talent use a range of techniques that anyone can follow, to become confident, capable and influential when speaking in public.

This chapter is for anyone who needs to speak in front of an audience, whether at a sales meeting, a professional business presentation or an after-dinner speech. It will show you the techniques that speakers have honed and used over many centuries to ensure that their audiences listen.

The five parts of speaking

The great Roman orators divided the art of speaking, or rhetoric, into five parts. A properly trained speaker throughout the Roman era and later ages was expected to master all five of these. They have dropped out of formal education over the last couple of hundred years, but are still very much the basis of writing and delivering great speeches and presentations.

- Invention

- Arrangement

- Style

- Memory

- Delivery

Invention

Invention is about creating the story you want to tell: finding the information, thinking about what you want to say, and really getting your ideas clear in your mind. This was, to a large extent, the subject of Chapter 3.

Speaker’s toolkit: defusing the BOMB

Before you even start to write your speech, talk or presentation, defuse the BOMB. If you don’t have good answers to these four elements, you risk getting it wrong.

Benefit

Who will be in your audience and why should they listen to you? If they will give you their time and attention, what will you give your audience in return?

Outcomes

What do you want to get out of your talk or presentation? How do you want to change your audience’s thinking, what do you want them to remember and what do you want them to do as a result of listening to you? Why are you speaking and what would be a great result?

Map

What is the story you need to tell and what are the key messages you want to get across? These will feed into the arrangement phase (below). In Chapter 5, you met the three secrets of persuasive argument: ethos, logos and pathos. How will you use these to make your case?

Background

Do your homework. Who will be in your audience and what will they know? What will their attitudes and expectations be? What information do you need to have at hand to build the detail of your speech or presentation and what additional information will you want to have in reserve to help deal with questions and challenges? There is an old rule: ‘Never present more than 20 per cent of what you know.’ That way, you will always have plenty of depth.

Arrangement

Next, you need to structure your talk or presentation to create maximum effect: to make it compelling, persuasive and powerful. We looked at this extensively in Chapter 5, starting with the classical approach that the Roman orators would have been familiar with: introduction, narration, division, proof, refutation and conclusion. We do not need to revisit this here.

Style

We have not yet spoken of style: the way that great speakers make it a pleasure to listen to them. This may seem like something of a dark art of professional speechwriters and playwrights, but all they have done is learned, practised and perfected the use of some simple, practical rules of language, which you can learn too.

Memory

There are three reasons why memory is important to a speaker:

- So that you can memorise what you are going to say. Speaking without notes narrows the emotional space between you and your audience, it creates more spontaneity and naturalness – and therefore increases your impact.

- So that you have a store of ideas and snippets that you can contribute to your speech to fill it with interesting asides, thoughtful insights and inspiring quotations.

- So that you can make your speech stick in the memories of your audience. We examined this aspect of memory in Chapter 6, but I will offer you an extra technique in this chapter.

Delivery

The last phase is how you deliver your speech, talk or presentation. In classical times, orators would practise each hand gesture, knowing that their audience would recognise a separate, parallel language in particular arm movements. Even today, the manner of your speech and the effect of your gestures and body language will contribute a lot to how people perceive what you are saying and how much they will want to listen to you.

Style

If you can make your speech a pleasure to listen to it will be one of your greatest talents. I have ten tips to offer you, to help make your style compelling, persuasive and powerful. As you start to build these into your speech, it will grow in impact.

Compelling style

1 Simple

Keep your language clear and easy to understand. Brief is better, and avoid unconventional uses of words or phrases that might jar with your audience.

2 Structure

Create a compelling sequence that is easy to follow and leads your audience to want to hear what is next. Signpost what is coming up, to help them to assimilate each section easily.

3 Surprise

A little surprise here and there will rekindle flagging attention and delight your audience. You can create this using misdirection, unexpected information or a dramatic image or metaphor, for example.

4 Suitable

Please don’t over-step propriety in trying to be surprising. Be aware of the occasion and suit your style and content to that. A best man’s speech should be different at the wedding reception from what is said at the stag event; a presentation to customers will differ from an in-house presentation to a sales team; and an informative talk about the environment will be different from a political speech on the same subject.

Persuasive style

5 Solid

You must convey ethos with real examples and evidence that is relevant to your audience and demonstrates your personal credibility.

6 Sound

Your logic must be sound, using reasoned arguments arising from demonstrable facts to create a case that your audience will find plausible.

7 Sentiment

Convey pathos by appealing to sentiment at the right time. Real-life examples and the human implications are the best way, but you can also consider talking honestly about yourself.

Powerful style

8 Stories

Stories don’t just convey pathos through visceral emotion, conjuring empathy and inspiration; they can also hold an audience spellbound, waiting for the next twist. Nothing is more powerful than a good story well told.

9 Shrewd

Offer your audience astute, penetrating and wise insights into your topic, so that they really want to hear your thoughts on your subject.

10 Stylish

Ornament your speech with some of the flowers of rhetoric: the clever ways that speakers have found to create patterns from words that entrance and delight listeners.

Speaker’s toolkit: rhetorical techniques

There are a great number of big academic texts, covering well over 400 rhetorical figures of speech that use language to create a pleasing or intriguing effect for the listener. And this is not the place to add another one. Even a sampling of the more common techniques is a tricky task. So rather than offer an orderly checklist, here are a few personal favourites, grouped under headings that should make it easy to remember the essential ideas behind them.

Making music with words

Rhythm, rhyme and repetition grab our attention, and when the first sound in each word is the same, we call it alliteration. Commonplace sounds are well-represented by words, such as ‘screech’ and ‘moo’. If you can invent new sound-words (called onomatopoeia) you will attract attention.

Patterns of repetition

There are so many patterns to choose from, starting with the most basic: ‘Yes, yes, yes’ (called epizeuxis). My favourites are:

- Starting phrases with the same word or words: ‘This royal throne of kings; this sceptred isle’ (anaphora).

- Ending phrases with the same word or words: ‘When I was a child, I spoke as a child’ (epistrophe).

- Ending one phrase and starting the next with the same word or words: ‘Fear leads to anger; anger leads to hate’ (anadiplosis).

Contradiction and contrast

These are some of the most widely used patterns, from ‘It is better to give than to receive’ to ‘One small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind’. John F. Kennedy – a brilliant speaker – combined this with repetition when he said ‘Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country’.

Amplifying or diminishing

Deliberate understatement – such as describing losing a limb as a flesh wound – or deliberate overstatement – like saying of a scratch ‘I am mortally injured’ – are established ways of drawing attention to something and also highlighting your attitude to it, often in a humorous way.

One thing in terms of another

Poets use metaphor and simile to describe one thing as another, or as being like another, to create a powerfully vivid imaginative effect. When you do it to explain something, this is an analogy. You can also describe things in terms of their components, like when you refer to your car as your ‘wheels’.

Messing with sentence structure

The most widely used deliberate effect is to structure a sentence into three parts: ‘I came, I saw, I conquered.’ Lists of three things have enormous power because of the rhythm they create, and the sense of completion they foster.

Memory

You will recall, I hope, that memory is important to you as a speaker for three reasons: to memorise what you want to say; to remember useful things to put into your talks; and to help you design a presentation that will stick in the minds of your audience.

Remembering your talk

There is a simple method that orators have used to remember speeches for thousands of years. All you need, to make it work for you, is a familiar building or route. Let’s say, for example, that you want to use your kitchen, and your speech has seven key points in it that you want to remember.

Imagine you are standing at the threshold of your kitchen, looking in. Start to your immediate left and sweep your eyes around the room slowly, from left to right, noticing things like windows, the sink, the cooker, the fridge, a table, a kettle, a toaster. Identify seven things that tend to stay where they are, so that you have seven hooks, in a sequence, which you will not forget.

Now start with the first key point in your speech. Perhaps, in your introduction, you want to remember to talk about the impact of last winter’s bad weather on sales. Your first hook is a window, so in your mind conjure up a vivid scene of snow drifts and blizzards through your window. The more powerful the image, the better. As you picture it, let yourself shiver for a moment: engaging multiple senses aids memory.

The next thing you wanted to talk about was the stockpiles of paper in your warehouse. Your next hook is the sink: imagine a pile of paper in your sink. Picture rolls of paper sticking out, loose sheets overflowing and the plug hole blocked. Make the image startling and comical for maximum recall-ability.

Then move on to the next point you want to make: how you have a plan to save this year’s profitability. This will get hooked to your cooker, so picture yourself, the hero, dressed in a superhero costume, saving a crumbling cake from the oven and pulling it out to see it stuffed with £20 notes.

You should now be getting the picture. This is called the Roman room method or, more technically, the method of loci (the word ‘loci’ simply means points). Because you are familiar with your room, or a route you travel frequently, remembering that part, in sequence, takes no effort. Vivid images – particularly if they are comical or rude – are easily recalled. By pegging the images to the landmarks in your room or on your route, you can easily commit a long sequence of memory points to your long-term memory with little effort. Reviewing the sequence a few times will make it easy to mentally scan to the next point and see the vivid image, causing you to recall the next point to make.

Mind maps

Mind maps have been around for centuries, but were popularised (and the term protected commercially) by Tony Buzan in the 1970s. These are a way of mapping out a set of ideas in a graphical way and are useful for speakers both to develop their content and sequence, and then to memorise it. However, the memorisation part works in a very similar way to the Roman room method; using images pegged to places on a map. If you are not familiar with mind maps, they offer a new way of note-taking, creative thinking and assisting memory that will be worth investigating. Buzan’s books are still the best on the subject.

From the laboratory: the science of memory

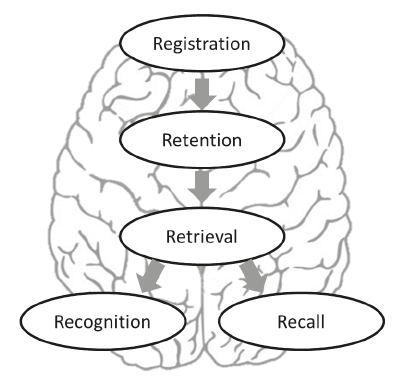

You can think of your memory as working in three stages:

Stage 1: Register the information

Lots of memory goes wrong here – it falls at the first hurdle. Stuff goes ‘in one ear and out the other’. To register it you have to get the information to stop in the middle! So to help you, when you get new information, do something with it: in your mind, comment on it. Make a link between it and something else you know – repeat to yourself.

We have two distinct memory processes: long-term and short-term memory. Your short-term memory can drop an idea in seconds, so remarking on the idea – stopping it on its way back out of your head – gives you the time to move to the next step.

Stage 2: Retain the information

This is the step where you transfer information into your long-term memory. We do it by rehearsing the information: cycling it through our short-term memory enough times to cause the chemical changes necessary to create a long-term memory.

There are two main processes of rehearsal:

- The phonological loop – the repetition of words.

- The visuo-spatial sketch pad – the creation of images and imagined objects, and using sounds, smells and your other senses.

There are two main types of long-term memory:

- Knowing that – called your declarative memory. The two principal forms are semantic (ideas and knowledge) and episodic (things we experience) memory.

- Knowing how – called your procedural memory.

Stage 3: Retrieve the information

There are two primary forms of retrieval: recall and recognition. Could you remember the name of the star of the movie Gladiator?

If you can, that is recall. If you cannot, but remember it as soon as I tell you it was Russell Crowe, that’s recognition. The trick is to move from recognition to recall by using the memory techniques to help you.

HOW MEMORY WORKS

Storing useful information

One way to start a talk is with a pithy quote, or perhaps a reference to an unusual event from the news, or possibly a description of some interesting research you read about in a magazine. But how will you remember these things and have them available when you are writing your talk?

For hundreds of years, people who need to speak publicly have been storing up these useful snippets in notebooks, known as commonplace books. Many famous people have even published theirs, giving us all access to the witty remarks and fascinating snippets recorded by people in public life. You can keep one too, by keeping a simple notebook with you at all times.

And if you are a more high-tech sort of person, why not use one of the many note-taking apps available for smartphones? Some of them easily share information across all your devices, making it straightforward to copy-and-paste the quote from your notes app to your presentation notes.

Helping your audience to remember

We covered this in Chapter 6, but I’d like to offer you one more specific extra technique, which is a great tool for speakers: the memory anchor.

We know that vivid images, smells, sounds and other sensory information are more easily remembered than abstract facts. If you can link a fact, idea or piece of information to some vivid stimulus, you can create a deliberate anchor in the minds of your audience. Whenever they are exposed to that stimulus again, the act of recall will bring back with it the idea that you attached to it.

So, for example, if you want your audience to remember a powerful sales slogan, then exposing them to it alongside a vivid image, with a strong dominant colour and a distinctive tune, will cause them to anchor the slogan to the image and sound. Replaying the sound with the image will trigger recall of the slogan. Making the image easy to recall on its own will bring back the slogan with it.

In case you are wondering if this works, this is precisely how a large number of adverts are designed to work. More hidden persuaders!

Delivery

Delivery is a big topic. So I have divided it into three sections:

- Preparation

- Speaking

- Handling questions and challenges

Preparation

We are nearly ready to think about your big moment: delivering your speech, talk or presentation. But not quite yet: first, you need to prepare. There are three things we need to cover: rehearsal, mental preparation and physical preparation.

Rehearsal

The amount of rehearsal you need to do is a personal matter, but if your talk really matters, then do more than you think you need to. Ironically, the shorter your talk, the more rehearsals you will need to do, to get your comments sharp and pithy.

If you have a presentation that matters a lot and you are not an experienced speaker, then it will be well worth working with a good friend or colleague to act as a rehearsal buddy or coach. If you can, also rehearse with a friendly audience. At least four (ideally seven) run-throughs will prepare you well. Here is a seven-step routine. If you are pressed for time, drop steps 2, 5 and 7.

- Run through your notes, on your own, to start to learn the content. You may need to do this a few times. Improve your recall by testing yourself.

- Run through the talk on your own, with no notes. This will help you to consolidate your memory and spot where you need to focus.

- Run through your speech with an observer or coach. Ask them to give you three points for you to focus on to improve your performance.

- Have another run-through with an observer or coach – working on your three points. Ask them to give you feedback on the changes and to offer three more points.

- Repeat as often as you have time for.

- Have a run-through with a friendly audience to simulate interaction. This ‘dress rehearsal’ should give you confidence. Get comments.

- Final run-through with audience. This is all about confidence. If you must get feedback, ask for one thing only to focus on.

Mental preparation

Mental preparation is about dealing with nerves. Many people get nervous when they think about the prospect of speaking in front of an audience. What you need to distinguish is the difference between:

- friendly nerves, which get your adrenalin pumping and raise your alertness, so you can do a great job;

- crippling nerves, which send your stress levels sky high and leave you panicked and fearful.

An example

Jack and Jill were waiting in the wings to speak at their company’s annual conference. Jack said to Jill: ‘I’m terrified. My heart is racing, I’m sweating all over, my hands are shaking and I just know I am going to make a real mess of this.’ Jill replied: ‘I know what you mean. My heart is beating so hard I can feel it, I am hot and bothered and my legs feel wobbly. I just know that I am pumped up and ready to go on stage.’

Having nerves is not a problem: it is how you interpret them. There are six processes that will calm you and put you in control of those nerves.

Acknowledge and confront your nerves

You are nervous. Pretending otherwise won’t accomplish anything, so acknowledge it. When you do that, it will rob the fear of its power. Notice what a good thing your nerves are: they tell you that this is important and you are taking it seriously.

Believe in yourself

You have invested a lot of time and effort getting to where you are. Mentally check through all the positive things you have done to prepare, from research, thinking and your experiences to date, to the work you did designing your talk and rehearsing it. One trick that works for me is to remind myself that if I miss something out or don’t explain something with the nice turn of phrase I have prepared, then I will know – but no one else will. My audience will judge what I do and say, not what I don’t do or forget to say.

Relax

The simplest way to relax yourself is a few deep breaths. Sit or stand upright with a good posture and take six really deep breaths, exhaling as much air as you can between each. Not only do deep breaths send signals to your brain that damp down the release of stress hormones, but they also put a larger supply of fresh oxygen into your blood. This will help your brain work more effectively, making your responses to your audience more resourceful.

If you have long-term stress or stage-fright problems, try learning and practising a meditation technique, such as transcendental meditation or yoga. This will have huge and lasting relaxation benefits. You can find out more about this in my book Brilliant Stress Management.

Speaker’s toolkit: calming breathing

Stand up and take six deep breaths. Each time, inhale as deeply as you comfortably can and exhale slowly. Make each cycle last longer than the previous one. Each time you breathe out, feel your shoulder muscles relax.

Self-talk

We all talk to ourselves. The question is, what do you say? If you are beating yourself up about gaps in your preparation, worrying about possible pratfalls or reminding yourself about past bad experiences, none of that will help you in any way.

If, on the other hand, you remind yourself about all the preparation you have done, all the past successes you have had and all the ways it can go well, you will help calm your nerves and prepare yourself to succeed. Be your own best friend and coach: talk to yourself as your best friends would talk to you.

Visualisation

Visualisation is an under-used resource. Our minds don’t distinguish well between reality and fantasy. So prepare yourself by visualising yourself going on stage, fully prepared, and delivering a first-class presentation or speech. See it in vivid Technicolor. Notice little details, such as how confident you are feeling and how the people in the front row are smiling and nodding when you make your points. Hear yourself speaking clearly and fluently.

Rehearse like this two or three times and, when you approach the stage for real, your unconscious mind will associate good, positive feelings with the experience, and you will start to feel more confident.

Posture

Although posture might be part of physical preparation, the underlying process is mental. Getting your posture right can come most easily from visualising. Stand upright, lightly on your feet, imagining a puppet string attached to your head, pulling you gently upwards. Relax your shoulders, imagining the muscles of your arms melting like chocolate to drip off your fingers.

Now imagine that there is a bubble around you. Imagine it growing and extending outwards, filled with your energy. Keep your mind on the centre of your body, just below your navel, and imagine it solid and unshakeable. These steps will calm and centre you.

Now to boost your energy and confidence. If you want to feel happier and more enthusiastic, gently look upwards, turning your head to the ceiling. As you do, allow your mouth to widen into a broad smile. Hold this posture for 30 seconds. Then repeat.

If you want to feel more confident and assertive, widen your stance, so your legs are slightly wider than shoulder width apart. Now put your hands on your hips, with your elbows outwards. Pull your shoulders back and allow your jaw to come forward a little bit. Hold this posture for 30 seconds. Then repeat.

From the laboratory: the neuroscience of panic attacks

When your hands shake and you start to feel faint, you may be having a panic attack. Don’t worry: nothing bad will happen – it is just your sympathetic nervous system going into overdrive. Along with a release of 20 to 30 hormones, your amygdala – the fear centre of your brain – is becoming over-active. Other brain areas also kick in – including a part of your mid-brain called the periaqueductal grey. This region prompts reactions such as freezing or running away, two of the most common responses in speakers who fear the stage.

You can calm this by noticing and acknowledging it, describing to yourself how you are feeling, deep breathing, and positive ‘I’m okay’ self-talk.

Physical preparation

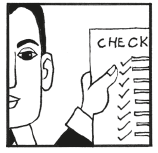

Physical preparation is about making sure everything is ready, so here are some checklists you can use.

Speaker’s checklist: what to pack

- Travel documents: tickets, reservations, ID, maps.

- Equipment: laptop, projector, power leads, timer or watch, music player and music.

- Accessories: remote control, pointer, adaptors for foreign sockets, extension leads, connection cables.

- Stationery: pens, notepaper, pencils, marker pens.

- Personal items: phone (and charger), business cards, purse/wallet, umbrella.

- Materials: your notes, printed materials, reference documents, props.

- Backups: USB or SD drive, login details for cloud backup.

- Vanity items: make-up, tissues, comb, breath mints.

- For emergencies: masking tape, gaffer tape, penknife, sticky notes, plain paper, sticky tac, scissors, painkillers.

You can download a checklist to print and use at www.speaksopeoplelisten.co.uk

Speaker’s checklist: checks to make on arrival

- Visual technology: Does it work? Run through everything. Are laptops running on power? Are screen savers or alerts disabled?

- Audio technology: Test the microphones, check you have spare batteries.

- Sight-lines: Are chairs well placed? Where will you stand? How clear are visual aids?

- Supporting materials: Have participants got all the materials they need?

- Small equipment: Check you have what you need – such as marker pens, pointers, notepaper and pen, watch or timer.

- Comfort: Ensure there is water (not fizzy and not iced if you are speaking) and tissues to hand.

- Distractions: Empty your pockets, remove dangly bracelets, put away unnecessary potential distractions.

You can download a checklist to print and use at www.speaksopeoplelisten.co.uk

One thing not to forget is your appearance. For many people, taking care of their appearance is a part of a routine that helps calm them and make them feel more confident. Dressing well will often boost your sense of self-esteem and presence, so aim to dress a little better than you expect your audience to dress. Make sure that your clothes and shoes are comfortable, so that they do not distract you, and ensure that no aspect of your appearance (typically ties, cufflinks and flies for men, earrings, necklaces and décolletage for women) grabs more attention than your words. My top tip is to pop to the cloakroom just before you are due to start, to make yourself comfortable and to use the mirrors for one last chance to get your clothes straight.

Speaking

pep (noun): energy, high spirits, vitality, vigour

PEP (acronym): passion, energy, poise

Good delivery has PEP. In front of an audience, you need to demonstrate your passion and commitment for your subject, energy and enthusiasm in your delivery, and poise in the way you carry your body and words.

This is vital because your emotional cues don’t just leak out, betraying the way you feel about your story, your audience and your presence in front of them: they gush out. One way or another, consciously or not, this is the message your audience will take from your speaking. PEP ensures they focus on the message you intend.

This section is about how to put PEP into your delivery. If you forget all the guidance that I gave you in Chapter 5, about drafting a compelling, persuasive and powerful talk or presentation, or the six steps of classical speech-building, remember this: every talk has a beginning, a middle and an end.

Beginning: opening

Your opening is where you grab your audience’s attention. Here is where they decide whether to listen to you. If they decide ‘yes’, there is still plenty of scope to lose them later on but, if they decide ‘no’ at this early stage, it is very hard to ever regain their attention.

A punchy opening line can seize the initiative from your audience, but many of them need a little time to settle in and feel comfortable. You have a few minutes during which your audience will make up its mind about you, so it usually pays to start a little more slowly.

You need to ‘play the odds’. Some audience members, the graduals, need to process information slowly, and diving in with a high impact opener and a fast pace will leave them behind, feeling overwhelmed and uncomfortable. Others, the rapids, process information extremely quickly. They like the high velocity, hit-and-run style opening, but they can cope with a bit of slow, as long as it doesn’t go on too long and start to bore them.

Making your platform your own

At the beginning, you need to start to ‘own’ your platform. It is a space and you must dominate it. When you come on, put down any props you have carried in and take charge. A powerful technique to help you do this is to imagine that you and your energy occupy a bubble, like a soap bubble, which surrounds you. As you take your stage, imagine that bubble steadily growing to fill all the space on the platform. Why stop there? Let it expand further to push back and then encompass the first row of your audience, the second … all the way to the back. When you have this sense, people will read it as charisma.

Use what is often called the lighthouse technique, to scan across your audience, catching individuals’ eyes and holding contact for two or three seconds before moving on. This gives audience members the uncanny and intimate sensation that you are talking directly to them.

Speaker’s checklist: openers

Here is a list of 20 alternative ways to open your talk.

- State something familiar – then undermine it.

- Make a bold claim for your talk – which you can deliver on.

- Assert something surprising.

- Make a provocative remark.

- Make a paradoxical statement.

- Offer a prize for something.

- Ask your audience a question.

- Give your audience a short quiz.

- Take a poll (show of hands) of your audience.

- Ask for someone who fits a description – the characteristics will be relevant to your talk.

- Tell a story – real life or allegorical.

- Use state elicitation – get your audience into a mood or emotional state.

- Describe a common experience that your audience will share.

- Describe a scenario and ask a question, such as ‘What would you do?’

- Challenge your audience.

- Recount a current or recent news story – which you will show is relevant.

- Quote a quotation.

- Make a demonstration – call for a volunteer first to really get them on edge.

- Draw an analogy between something familiar and your topic.

- Make a humorous observation – but be very careful with jokes unless you are very accomplished.

Middle: impactful delivery

I am going to assume that you have designed a compelling, persuasive and powerful talk to engage and hold your audience. But how can you deliver it to maximise the impact that it has? You have five assets that can enhance (or undermine) your delivery:

- Verbal delivery – your words.

- Rhetorical delivery – the patterns of your speech.

- Vocal delivery – your voice.

- Physical delivery – your posture, gesture and expression.

- Speakers’ aids – anything you bring with you to add to you and your voice.

Verbal delivery

The words you choose are important – and we spoke a little about them earlier in this chapter, under ‘style’. Choose natural, everyday language where you can, using simple words that everyone in your audience will understand straight away. Also use:

- Sensory language: This is the language of seeing, hearing, touching, feeling, smelling and tasting. It makes it easy for your audience to conjure up powerful mental images and will distinguish you from the bland or confusing speakers who stick to abstract conceptual language and management-speak.

- Positive language: Saying what you mean makes it quicker for your audience to understand you than if you tell them it’s not what it isn’t. And if that sounds a bit confusing … that’s my point. It takes our brains just a little longer to process ‘not unhealthy’ than to process ‘healthy’. That eats into your audience’s comprehension and their eagerness to listen.

- Powerful language: In Chapter 5 (page 84), we saw how some special words have great power. Add people’s names to that list. When you are speaking and interacting with an audience, using audience members’ names can really get people listening. Finally, some of the most powerful language of all is no words at all: silence.

Rhetorical delivery

The section on style earlier in this chapter offered you a brief introduction to the power of rhetoric to build rhythm and timing into your speech, with repetition, contrast and threes. Careful use of linking to build connections back to earlier parts of your talk also serves to underline its coherence and build a larger pattern, which audiences find appealing.

It is perhaps ironic that rhetorical questions have less rhetorical power than real questions, when you pause your delivery to ask a question of your audience, and wait for an answer. Why is this?

When you ask a question, your audience immediately processes it as a need to pay greater attention and search for an answer. Not answering it yourself – as you would with a rhetorical question – adds to the pressure on your audience to pay attention. When you invite someone else to answer, many of your audience will listen hard to compare their own answers to the ones given, heightening attention again. And when you resume speaking, the audience has had a break from your voice and listens to you with renewed alertness.

Vocal delivery

Your voice is like a musician’s instrument or a carpenter’s tools – it is the immediate means by which speakers do their job. Yet how many of us take the time to hone it? Professional voice coaches, whether in acting, singing or voice-over, identify many ways to vary your voice. Putting them together will make your voice a rich and powerful tool.

Speaker’s checklist: voice – ten things you can vary

- Pace or speed: Slow down for emphasis, speed up to convey excitement. Many of us need to slow our day-to-day pace for public speaking. Speaking too quickly will frustrate some listeners and not give you time to vary anything else.

- Volume or loudness: You need to be easy to hear without booming. Lower your voice to draw your audience in and create intimacy. Practise deep breathing so it becomes a habit when you speak. More breath means more air; more air means louder volume.

- Pitch or tone: The lower end of your register carries more weight, and variety keeps you interesting. Tone primarily carries emotional cues.

- Modulation – how pitch varies through a sentence: Go up at the end for a question, down at the end to deliver a powerful point. Flat tone throughout is monotonous and ambiguous.

- Cadence or inflection – how pitch varies through a word: Use inflection to add particular stress and interest to your speech.

- Stress or emphasis of a word or phrase: Pick out the words that carry the burden of your message and emphasise these with pitch, pace and volume. Try repeating the following sentences, changing the word you emphasise each time. Each word can be emphasised to get a different meaning every time: ‘I never said she stole that money’; ‘I was born in London’.

- Rhythm – patterns of speed and emphasis: Rhythm can make listening easy – sometimes too easy, when it becomes hypnotic. So vary it by varying pitch and pace.

- Timbre – the quality of your voice: From nasal, to gravelly, to breathy, to raspy, to mellow, to clear, to crisp, to clipped – we all have a vocal quality, partly dictated by our physiology and partly by how we use it. Breathing and facial expression are the keys to getting this right. Try saying the following sentence when smiling and then when frowning: ‘I had a lovely time at your party.’

- Locus – where you project your voice to: Some people speak loudly yet few hear – the words get trapped in their mouth. Open your lungs and your mouth and project the sound to each corner of the room.

- Accent and pronunciation: These combine many of the other factors to create a distinctive regional and social voice and speech pattern.

One of the simplest ways to introduce power to your voice is to increase your use of pauses. They create tension and give your audience time to consider what you have said. They also slow you down and give the impression of a deeper tone to your voice, thus conveying greater authority. Practise mentally counting ‘one, two’ at the end of each sentence to get a feel for how much to allow at the end of a ‘standard’ sentence. Use a longer pause – or indeed a shorter one – to create a specific effect.

Developing your voice is a whole study in itself and there are many excellent books and courses that can help you. They will give you exercises to address all the ways you can develop your voice.

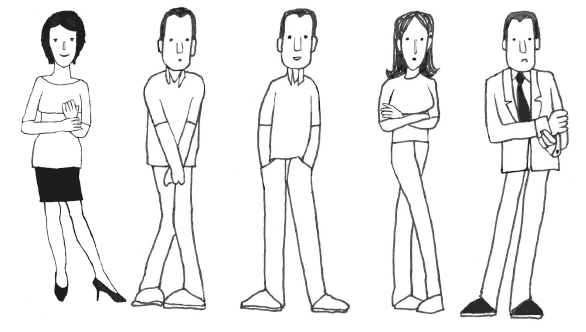

Physical delivery

Your body posture can be a direct give-away of your mental state. We have already considered eye-contact, and you know that smiling will not only portray warmth and confidence but also improve the quality of your voice, but how about the way you stand?

That question, by the way, implies that you are going to stand. That should be your default: it gives you more height, opens out your chest for greater breath volume and portrays confidence and respect.

The best posture is upright, with your back neither arched nor hunched. Stand facing your audience, square on to them. Keep your posture as symmetric as you can, because asymmetry is often read unconsciously as a sign of discomfort or even deception. Here are a few more things to beware of:

- Hand-cuffs: Holding your hands rigidly together to still a fidget is just as distracting as fidgeting.

- Fig leaf: Avoid standing with your hands together in front of your genital area.

- Pockets: Hands in pockets work for some speakers, but not all. If you must do it, empty your pockets first and keep your hands still inside them.

- Crossed feet: Not only does this look precarious (or that you are in a hurry to get to a bathroom); it is unstable. Women do this a lot. Feet hip-width apart is stable and looks good. If you want to come across as more dominant, go for shoulder width.

- Cuffs and collars: Playing with your cuffs or your collar and tie for men, or your bracelet or necklace for women will make you look nervous.

The flip side of this is the use of deliberate gestures to convey emotion and enhance the impact of your words. If you gesture with your arms, make the movements echo your words. For example, spell out a sequence of three points on your fingers, or gesture from right to left to signify the passing of time. Think about that second one: in the West we tend to picture time as moving from left to right. When you gesture right to left, your audience sees left to right. Very few speakers do this, but when they get it right it is very powerful.

POOR SPEAKER POSTURE

Speakers’ aids

This book is called How to Speak so People Listen, so visual aids and demonstrations are pretty much out of its scope. However, I do want to make a few points and give you a few tips.

Firstly, visual aids should be visual aids. Don’t let them dominate, and make sure they help you. And by help you, I mean help you to communicate – use them to support your audience in hearing, understanding and remembering your message. They are not to support you in remembering your speech or the three points you wanted to make at slide six.

If you are using projected images, what I suggest is that you keep the words on your slides to an absolute minimum, and use strong and relevant images that either help understanding (such as diagrams), reinforce memory (such as powerful photographs) or simply entertain (such as cartoons). If your slide contains a lot of information, such as a graph or a long quotation, here is how I would present it:

- Signpost what is coming up, using words only, so that your audience knows what it is going to see.

- Put the slide up.

- Saying nothing, turn to look at the slide. This will direct your audience’s attention to it.

- Continue looking at it for enough time for your audience to assimilate what is on the slide, still saying nothing.

- Turn conspicuously to face your audience. This movement will draw their attention back to you. If you got your timing right, there will be no conflict for them over where to give their attention.

- Now you have their whole attention, make your comments about the slide, offering interpretation, insight, explanation or challenge that adds to what they already learned from it.

Speaker’s toolkit: designing effective visual aids

The two most used tools on the market for professional presentations are Microsoft’s PowerPoint and Apple’s Keynote, but do also consider various cloud-based options, such as Prezi or SlideRocket. Whichever you choose, the key is to use them well. Here are some tips:

- Don’t be cleverer than you need to be to communicate clearly. Fades, transitions and animations, for example, usually just detract from your speaking.

- One idea per view.

- More images; less text.

- Space and emptiness is as powerful on a slide as silence is in speech.

- Use one font (at most two) throughout and keep all text to a large enough size to be read easily from the back of a room (28pt or more). A quick test: stand two to four metres from your computer screen. If you can’t read the text clearly, make it bigger.

- Use contrasting colours for text and background, and keep backgrounds simple to avoid distracting attention.

- The rules of three helps good design: 1. Divide the screen into a three by three grid; use the horizontal or vertical thirds to place objects pleasingly; 2. Never have more than three elements on an image; 3. Three similar objects will look better than two or four.

- Use colour for interest and impact. Adopt a colour theme for text and graphics, using house styles rigorously where you have them. Avoid using red, orange and green to draw distinctions – an inability to distinguish these is the commonest form of colour-blindness.

- Learn how different colours are interpreted. This is culturally determined and varies from country to country. In the UK black = authority, dark blue = trustworthy, yellow = optimism, purple = creative, red = risk and excitement. And learn what colours work well together and which ones clash. Adobe’s Kuler web app (and others like it) is a great asset in creating pleasing colour combinations.

- Simplify charts and diagrams to carry one clear message, and optimise layout, colour and labelling to make your message easy to assimilate.

- Always proofread at least two days after you created your slides – and get someone else to do it too.

End: closing

The end of your speech, talk or presentation gives you the opportunity to achieve three things:

Pathos

Use the power of emotion to strengthen the impact of your message. Tell a brief story, conjure up some consequences of either action or inaction, or use a telling quote, for example.

Summarise

Summarise what you have said, giving the chance to use ‘recency’ to nail memorability one last time.

Now is the time to give a clear, easy-to-remember summary. Can you do it in three points? Can you use a rhetorical technique, like alliteration, rhyme or two things similar then one different, to make them sound good? Can you do it in under a minute? If you can do all these, your summary will stick, and your audience will be ready for your final …

Call to action

Give a short rallying call to tell your audience what they must do next; the simpler and sooner the better.

Speaker’s checklist: closers

I have grouped my examples of closers under the three components mentioned above, but with some creativity, many can be adapted to other purposes.

Pathos

- Tell a story.

- Give a personal anecdote.

- Use a quotation.

- Close a loop – finish a story that you started earlier on and left unfinished. Alternatively, offer the moral of a story you told earlier.

- Summon up an emotional state in your audience.

- Describe what it will feel like when the audience has made the change (which you will reiterate in your call to action).

- Ask a rhetorical question, and answer it with an easy-to-remember answer.

- Do or say something unexpected – then explain the relevance.

Summaries

- Make three simple points.

- List the benefits or valuable applications of what you have said.

- Use counterpoint: this, not that.

- Restate the problem and then your solution.

- State how your points prove your argument.

- Make a clear and definitive statement.

- Link back to your opening.

- Transform your central idea into a simple slogan.

Calls to action

- Make a conditional close: ‘If this; then that.’

- Give instructions – in steps.

- Lay down a challenge to your audience.

All three in one

- Repeat a word or phrase in three consecutive sentences, for example: ‘It’s been a pleasure to speak to you today. It’s been a pleasure to put forward some exciting ideas for you. And I’m certain it will be a pleasure to for us all to see the results next year. Thank you!’

Handling questions and challenges

So it’s over: you have given your speech, made your presentation or done your talk. But oh, one moment, the audience has questions.

Handling questions

Let’s start with a simple four-step approach to handling a question.

Step 1: Listen intently to the question, turning your whole body towards the questioner and approaching them if the space allows. Use good eye-contact and good listening.

Step 2: If you have not got it already, get their name, and thank them for their question.

Step 3: Repeat the question back to check your understanding; first use the same key words and phrases that they used and then restate it in your terms to confirm that you understand what they want to know or the point they have made.

Step 4: SCOPE the question: stop, clarify if you need to, think of options for how to respond, proceed and evaluate your response by observing reactions and asking for feedback.

Handling tough questions

If the question was in the form of a challenge or a disagreement, always start by highlighting where you agree, so narrowing down the scope of the disagreement. Then clarify whether it is the underlying facts, the method of analysis or the interpretation that you disagree on. The rest, you can bank as agreement. The more you agree on, the easier it will be to build rapport.

If you are with a colleague and you need help, flag up your need without dumping them in a hole: say something like ‘Thank you for your question. In a moment I will ask my colleague for her views, but let me give you my thoughts first.’ This will give your colleague a chance to think through their response.

In the absence of a colleague, you might do the same, but throw it open to the rest of the audience. This is especially helpful if you suspect the questioner is making mischief or just not getting it.

You may, by the way, recognise that they are right and you were wrong. In this case, there is only one approach: admit it, thank them and modify your position.

Handling resistance

Sometimes, however, you will be right, and yet an audience member will resist your answer. If this happens, stay calm and listen carefully to what they say. Use this to diagnose the nature of their resistance, and respond appropriately. You will find an analysis of the six principal types of resistance, and how to deal with each one, in my short book The Handling Resistance Pocketbook.

The YES/NO of public speaking

YES

- Give your presentation PEP: passion, energy and poise.

- Prepare mentally and physically, and rehearse often.

- Accept nerves as meaning you are properly excited.

- Make use of pauses and silence.

- Start slowly.

- Vary the pitch, pace and loudness of your voice.

- Close with pathos, summary and a call to action.

NO

- Avoid reading anything, except direct quotations.

- Don’t let your visual aids dominate – they should be an aid to your audience in enjoying, understanding or remembering what you say.

- The same goes for your clothes and accessories – don’t let them be more interesting than your presentation or speech.

- Don’t get fazed by difficult questions. Stay calm and respectful, and SCOPE the question.