2 A Model for Workforce Planning

U.S. Agency for International Development

Carolyn Kurowski

John Salamone

Ashley Agerter Raitor

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) has developed and refined a comprehensive strategic workforce planning model that it applies annually to understand its staffing requirements across the entire agency—in its regional and country offices overseas as well as its domestic headquarters. The model is web-based and is accessible to all USAID managers. It draws on critical strategic data within the agency, including budget plans and priorities, country characteristics, and programmatic requirements, to develop targeted staffing levels for the agency and its components, including workforce segments. The model also includes “what-if” features that allow managers to determine the impact of different strategic assumptions on staffing. USAID has been using the model for over ten years and has steadily refined it so that it is now an ingrained management tool. Both the U.S. Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and the U.S. Office of Personnel Management (OPM) have lauded the model and the useful way it informs staffing discussions.

Perhaps the biggest and highest impact change USAID has achieved is a shift to data-based discussions of staffing. Far too often, staffing discussions become internal political battles— contests over whose function or organization is perceived as more important or more in favor—with limited critical assessment of the bottom-line staffing requirements necessary to achieve important strategic results. At USAID, the tenor of staffing discussions has shifted 180 degrees. The real questions are about the agency’s strategic requirements. Aided by the model, staffing flows directly out of that strategic understanding in a highly objective, neutral way, facilitating agreement and acceptance among internal managers.

The design and ongoing refinement of USAID’s model offer clear best practices that other agencies could leverage. Although extensive analysis would be required to adapt the tool to the specific strategic environment of another agency, the architecture of the model is easily transportable. As with many best practices, the important lessons to be learned are less in the final product than in the journey the organization took to get there.

About USAID

Following the success of the Marshall Plan and the Truman administration’s Point Four Program, President John F. Kennedy signed the Foreign Assistance Act in 1961, creating the United States Agency for International Development. Since its inception, USAID has been the leading U.S. agency for providing assistance to countries recovering from natural disasters, trying to escape poverty, and engaging in democratic reforms. By diminishing these underlying conditions, which are often linked to instability and terrorism, USAID plays a vital role in achieving and maintaining national security.

The agency comprises a large, diverse, and distributed workforce. USAID administers foreign aid through a decentralized and relatively complex staffing structure. Employing over 10,000 staff, the agency is headquartered in Washington, DC, and operates in approximately 100 countries across sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, the Middle East, Latin America, and the Caribbean, as well as Europe and Eurasia. From health officers fighting malaria in sub-Saharan Africa to democracy officers promoting free and fair elections in Egypt and Tunisia, USAID’s success depends on its ability to assess, manage, and leverage its unique, dedicated, and highly skilled workforce effectively and strategically.

Setting the Context

In August 2003, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) released a report to Congress that identified human capital management as a high-risk area at USAID, given the agency’s primarily ad hoc approach to workforce planning. At the time of GAO’s study, USAID was in a period of transition, having evolved from “an agency of U.S. direct-hires that largely provided direct, hands-on implementation of development projects to one that manages and oversees the activities of contractors and grantees…. this trend has affected USAID’s ability to implement its foreign assistance program as the number of U.S. direct-hire foreign service officers declined and much of USAID’s direct-hire workforce was replaced by foreign national personal services contractors.” (GAO-03-946, 6) In fact, the number of USAID direct-hires decreased by over 60 percent from 1962 (8,600 direct-hires) to 1990 (3, 162 direct-hires). This period was followed by a reduction in force and hiring freeze in the mid-1990s, which further depleted the agency’s cadre of direct-hire staff, creating a heavy reliance on contractor support.

GAO further reported that several human capital vulnerabilities resulted from USAID’s not having a strategic workforce planning system in place during this period to help manage the transition and anticipate future requirements. For example, “increased attrition of U.S. direct-hires since the reduction in force in the mid-1990s led to the loss of the most experienced foreign service officers, while the hiring freeze stopped the pipeline of new hires at the junior level. The shortage of junior and mid-level officers to staff frontline jobs and a number of unfilled positions have created difficulties….” (GAO-03-946, 14) In addition, GAO reported that USAID lacked the necessary surge capacity, which is imperative for an agency that responds to unpredictable events and changing political environments.

To address these vulnerabilities, GAO challenged USAID to develop and implement a strategic workforce planning process that would mitigate human capital risks and plan for the future of the agency. The question is: How does an organization implement an effective workforce planning process for an interdisciplinary, globally dispersed workforce, ensuring that it is equipped to respond to political upheaval, natural disasters, and economic meltdowns in an ever-changing international landscape?

USAID’s Consolidated Workforce Planning Model

In response to GAO’s report, USAID’s Policy, Planning, and Information Management (PPIM) division initiated a comprehensive workforce planning effort, with the goal of putting the right people in the right place at the right time. PPIM quickly realized that to achieve that goal, a consistent model was needed to help it make institution-wide decisions regarding staffing. USAID developed the consolidated workforce planning model (CWPM), a web-based strategic management tool that uses assumptions based on strategic direction, subject matter expert ratings of diplomatic importance and development potential, funding data, and a variety of additional data-driven assumptions to predict the agency’s staffing requirements. While the tool has changed dramatically during its nearly 10-year existence, it remains guided by three critical design precepts:

1. Build for the future. The CWPM is a future-oriented tool that projects staffing needs and offers flexibility in response to changing circumstances. The model can be adjusted to reflect a variety of organizational, business, and staffing scenarios. For instance, the number and type of program funding can be adjusted up or down and the model will project the corresponding staffing requirements across different functions. This flexibility has enabled USAID’s leaders to consider the workforce implications of changes in both the internal and external environments.

2. Consider the entire workforce. As its name conveys, the consolidated workforce planning model encompasses USAID’s entire, globally dispersed workforce. The tool includes a robust set of assumptions that project foreign service officers (FSOs), general schedule (GS) employees, foreign service nationals (FSNs), those on personal service contracts (PSCs) with the U.S. government, and other types of employees. The model takes into account USAID’s use of a variety of employment mechanisms to meet its various staffing needs; a core assumption is that the different employment categories present a unique set of staffing requirements. For instance, direct-hire employees should ideally be performing the long-term work of the organization while PSCs and other special employment mechanisms should be used to meet highly technical or specialized needs over a limited period of time.

3. Begin with the baseline. At its core, the model is a complex set of premises and assumptions about USAID’s workload. The starting point was existing data and information such as appropriated funds, ratios of staff to program dollars, and external measures of country concerns. Those assumptions are continually being refined to reflect USAID’s evolving future state. This involves gathering information from subject matter experts (SMEs), translating the agency’s strategic goals into workforce expectations, and vetting the data with agency leadership.

Example CWPM Workload Drivers and Assumptions

Base staffing: The CWPM assumes that certain functions and roles (e.g., senior managers, administrative staff) are common across all organizational units, regardless of the technical work performed by the unit. These functions are projected using standardized staffing ratios (e.g., one senior manager for every X staff managed).

Technical staffing: The CWPM contains dozens of unique assumptions and formulae that project workload for functions and roles that are unique to a particular organizational unit. For example, the workload for procurement staff in USAID’s Office of Acquisition and Assistance is driven by the number, type, and size of contracts managed, while key drivers for USAID’s regional bureaus (which design, implement, and evaluate regional and country strategies and programs) are the number and size of overseas missions they support.

Staff type distribution: In addition to projecting quantity, the CWPM contains a number of assumptions regarding staffing mix. For example, the CWPM projects a larger proportion of U.S. direct-hire staff in USAID’s Africa region compared to the Europe and Eurasia regions, where in-country staffing support is more readily available.

Workforce Analysis

Since the purpose of the tool is to forecast staffing requirements, USAID first needed to understand and identify the primary factors that impact workload. PPIM initiated a comprehensive workforce analysis to predict workload and staffing demands for the future, identify current workforce gaps, and develop solutions to address those gaps. To execute this study, the team conducted interviews and focus groups with various staff, developed and analyzed workload surveys, and bench-marked staffing levels for comparable work functions across the federal government to determine ideal staffing ratios and identify workload trends (Table 2-1).

Beta Model

The project team compiled the results of the workforce analysis and input them into the initial version of the model. The beta run revealed a number of apparent workforce gaps, particularly in the FSO employment category. For example, overages were identified in the PSC category based on the assumption that long-term work should be performed by direct-hire staff versus contractors. The gaps in these areas were indicative of broader workforce issues, including the need to ensure that USAID has sufficient direct-hire staff to serve as effective stewards of the public trust, the need for better training and career opportunities, and the need to transition individuals who are performing long-term responsibilities out of PSC employment categories into more permanent positions.

Table 2-1. Common Workload Analysis Questions and Implications

| Common Workload Analysis Questions | Implications |

| How much variability in time spent on key functions is there among the departments? | If all departments are spending a significant amount of time on the same types of tasks, there may be opportunities to reconfigure staff in order to streamline processes. |

| Are functions that employees view as most important consistent with management views? | Discrepancies between what employees and managers view as important may indicate a lack of communication or understanding regarding the alignment between job duties and overall mission. |

| What types of employees are spending time on specific functions? | Discrepancies between career level and functions can suggest a need to realign functions. For example, if higher-level employees are spending too much time on administrative functions, this work may need to be reassigned. |

| Do employees feel that their workload has increased, decreased, or remained constant? | If respondents indicate that they have experienced an increase in their workload, it may suggest that employees feel stretched and pressured. If employees continue to perceive their workload as increasing for the long term, they may become disengaged and experience burnout. This can affect the organization’s ability to retain high-performing staff. |

Following the model’s inaugural run, it became clear that the agency had developed an innovative tool that could be used to better understand USAID’s complex workforce and evolving staffing needs. However, the beta model was limited in terms of its functionality and the precision of information it produced. In addition, the involvement of senior leadership in framing the tool’s underlying assumptions—and institutionalizing the tool into broader workforce planning processes—needed increased emphasis.

Enhancements and Modifications

Given the data imperfections and lack of strong buy-in from senior leaders, PPIM kept a relatively close hold on the CWPM and its projections for the first several iterations. Recognizing that both of these aspects were key ingredients in establishing the tool’s credibility across the agency, PPIM instituted several important changes to refine the tool’s underlying assumptions and increase the engagement of senior leaders and other key players.

In 2008, a paradigm shift in several of the model’s core assumptions occurred. In an effort to coordinate USAID’s strategy with the national security strategy, PPIM partnered with the Department of Defense to develop new strategic drivers to ensure that the agency had the right number of personnel in countries that were important to the United States’ developmental, diplomatic, and security interests, regardless of program funding. As a result, the CWPM began to consider a number of country factors in determining staffing requirements, including economic growth and political stability. The algorithms that underlie these strategic factors leverage data from reputable external sources, including the World Bank Institute, the World Health Organization, and the International Finance Corporation. This new approach was aimed at establishing the tool’s credibility with agency leadership and other stakeholders.

In addition to addressing data quality and strategic alignment, PPIM began to recognize that the CWPM’s Microsoft Excel-based operating environment posed significant hurdles. At that time, the model existed as a set of interrelated Excel worksheets, which were tied together through complex formulae and references. As the CWPM increased in scope and complexity, it became increasingly difficult to identify and trace formulaic errors. In addition, the file-based design of the original tool limited the model’s accessibility to other USAID staff and key stakeholders. This lack of transparency contributed to misperceptions about the tool’s underlying data and its intended uses. PPIM routinely received feedback that other USAID staff perceived the CWPM as a “black box.” These usability and transparency issues posed significant risks for implementing the tool into broader workforce planning and resource allocation processes across the agency.

Ultimately, USAID required a new tool to mitigate these risks. In 2009, PPIM expanded the team to include more advanced IT skills with the goal of designing and developing a web-enabled solution. The stability, accuracy, and accessibility provided by the online application were key ingredients in the model’s successful implementation, allowing PPIM to focus its efforts on leadership buy-in, communication, and training, with the ultimate goal of increasing awareness and acceptance of the tool across the agency.

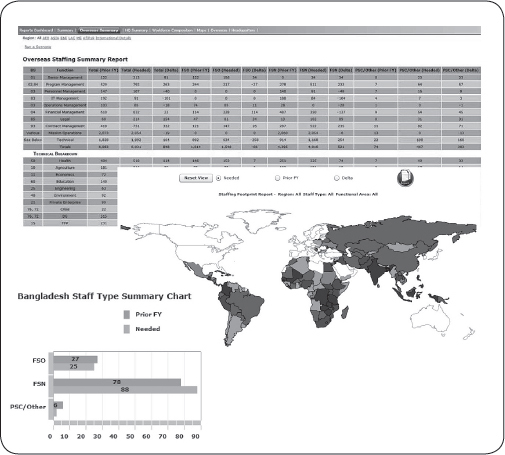

With its automated maps and charts, sound effects, and other “bells and whistles,” the new web-enabled tool was more visually impressive than its Excel-based predecessor (Figure 2-1). However, to ensure that the numbers projected by this flashy new tool were accepted by a wider, non-HR audience, PPIM needed to identify and establish champions who would advocate for the tool, align its assumptions with the agency’s strategic vision, and position its results in a meaningful way.

In 2010, PPIM established the CWPM steering committee. This committee comprises key leadership from HR and other areas of the agency, including the Office of the Administrator. The committee meets regularly to “ground-truth” the model’s results, review and authorize major updates to the assumptions and workload drivers, and ensure that the tool reflects current policies, statutes, and strategic direction.

FIGURE 2-1 Screenshot of the Web-based CWPM

Backed by the steering committee, PPIM officially launched the CWPM to users outside HR in November 2010. In support of this effort, PPIM partnered with HR to develop a robust suite of supplemental communication and training materials, including a workforce planning homepage on HR’s intranet, user guides, a set of frequently asked questions, and several computer-based training modules. The CWPM currently has more than 200 users from across the agency, the Department of State, and OPM.

Impact

The CWPM has become a valuable source of input into USAID’s planning and budgeting processes. By rationalizing and reallocating staffing based on stated workload drivers, the model has allowed decision-makers to understand and project the potential impacts of resource, organizational, and environmental changes on staffing requirements at headquarters and in the field.

For example, the Republic of South Sudan became an independent nation on July 9, 2011, effectively putting an end to Africa’s longest running civil war. When the country voted for secession, agency staff looked to the CWPM for guidance in workforce planning. After adjusting a few basic assumptions to reflect projected funding increases and the difficulty of conducting business in post-conflict states, the CWPM produced a detailed report that estimated the staffing support required to operate a mission in this newly formed nation.

USAID’s Development Leadership Initiative (DLI) provides another example of how the CWPM has truly become a cornerstone of the agency’s hiring and resource allocation process. USAID’s FY05 human capital strategic planning process and workforce analysis identified a “lack of depth in critical core areas such as education, health, and agriculture, concluding that this was severely constraining the agency’s ability to ‘surge’ staff in support of pre- and post-conflict programs in Iraq, other critical priority countries around the world, and other foreign policy priorities. These factors, coupled with a high percentage of USAID’s workforce nearing retirement, underscored the acute need for both increased hiring and better succession planning.”1

Backed by bipartisan support and supplemental funding, the agency launched the DLI program to address these issues, with the ultimate goal of increasing its cadre of FSO staff by 1,200 positions, effectively doubling the FSO workforce. The CWPM’s results have been used to guide the recruitment, hiring, and deployment of new FSOs under this large-scale effort. Specifically, USAID has targeted its hiring toward specific occupational categories (i.e., “backstops”) based on the CWPM’s staffing projections to achieve the right number of staff and the optimal skill mix.

In addition to recruitment and hiring, the model serves as a valuable deployment and resource allocation tool for the agency, which is imperative in a tight budget environment. A February 2012 report to Congress indicated that USAID is at approximately 75 percent of the staffing level projected by the CWPM, indicating that USAID is not fully staffed to meet its current workload requirements. Therefore, the agency has leveraged the model to institute a “fair allocation” methodology for mission-level staffing requests and deployment determinations. For example, the deputy assistant administrator of HR tasked the agency’s regional bureaus with incorporating the model’s projections into their official staffing requests by doing a country-by-country allocation to the CWPM’s bottom-line numbers for their respective regions. Recognizing that there weren’t enough resources to staff to 100 percent of the projected workload requirement, the goal of this exercise was to “structure the market” to match supply and demand more closely.

The reality is that missions in USAID’s Europe and Eurasia (E&E) region are often more attractive than Africa missions, but the staffing needs in Africa dramatically outweigh those of E&E. HR then worked with the bureaus to arrange region-by-region briefings with the State Department, which plays a key role in approving staff overseas. Ultimately, USAID used the model’s projections to help justify additional positions in mission-critical countries to State.

Overall, the agency has come to view the CWPM’s results as a general guideline for staffing requirements. In many cases, actual staffing requests differ from the model’s projections, due to budget limitations, space considerations, security concerns, and other practical realities that every organization faces. However, over the last 10 years, USAID has successfully leveraged this strategic staffing model to develop and institute a data-driven workforce planning process, which has helped the agency accomplish the following:

Align workforce requirements to the agency’s strategic goals

Develop a comprehensive picture of where gaps exist and identify and implement gap reduction strategies

Make strategic decisions about organizational structure and staff deployment

Justify staffing requests to Congress and other stakeholders, which is particularly critical in a difficult budget environment.

Why It Worked

Although USAID is a unique agency that requires a highly specialized workforce planning tool, many of the issues the agency faced in developing and institutionalizing the CWPM are similar to those that any organization would face. Similarly, the key ingredients to USAID’s success apply to any organization looking to develop a data-driven workforce planning process. Four key factors contributed directly to the agency’s success:

1. Engage senior leadership. USAID quickly recognized the importance of engaging senior leadership to establish agencywide buy-in and ensure that the CWPM’s assumptions and projections remain credible. For USAID, the process of updating the model’s data and interpreting its results has become an increasingly coordinated effort, as PPIM must frequently gather dozens of data points from across the agency. With support and guidance from the CWPM steering committee, PPIM has been able to create and sustain relationships with key individuals to ensure these critical data updates are received. The steering committee has also been crucial in establishing and maintaining the CWPM’s credibility. By routinely communicating key changes in strategic direction and reviewing and authorizing major changes to assumptions and formulae, the committee helps ensure that the tool remains relevant and aligned with overarching agency priorities.

2. Be clear about what a staffing model isn’t. From the beginning, USAID had a clear understanding of what the CWPM was and, equally important, what it wasn’t. A common mistake in workforce modeling is treating a model’s projections as “the answer.” By its very nature, a model is inaccurate because it’s precisely that—a model. A staffing model’s value is that it alters the starting point for the discussion. Rather than beginning a conversation by looking to current or historical configurations, the discussion begins with the allocations suggested by the forward-looking model. Managers still need to weigh the results and make staffing decisions based on other considerations; the staffing model helps frame that discussion in a clear, rational, and data-driven context that managers can understand and accept. USAID has come to view and communicate the model’s results as a general guideline for where the agency should be. A staffing model does not provide the right answer; instead, it offers a reasonable starting point based on data-driven assumptions.

3. Be transparent and flexible. To institutionalize the tool into broader agency planning and resource allocation processes, PPIM needed to shake the “black box” stereotype by increasing transparency and making the tool accessible to a broad, non-HR audience. This would not have been possible without transitioning from the cumbersome, Excel-based tool to a more intuitive and user-friendly web-based application. The stability and accuracy provided by the online application has allowed users to understand the CWPM’s assumptions more easily, navigate its robust suite of planning and scenario-building capabilities, and interpret its results more effectively.

USAID also understood that its optimal staffing profile is a moving target because workload ebbs and flows as policies, priorities, and processes change. PPIM had the foresight to build a high level of flexibility into the web-based application. With the click of a button, users can change staffing ratios, test the impacts of various funding levels, or adjust the relative distribution of certain staff types and functions.

4. Leverage external data sources. A key component of the CWPM’s credibility, both internal and external to the agency, is its reliance on unbiased, external data sources. Along with many other organizations across the federal government, USAID currently relies on a legacy human resource information system (HRIS) that is imperfect at best. It is cumbersome to navigate and error-prone, and extracting data is difficult. In contrast, the CWPM’s projections are tied to external predictors of workload, such as the relative ease or difficulty of doing business within a country (measured by factors such as the burden of customs procedures, investor protection indices, and the average time required to start a business); the impact of infrastructure on workload (measured by factors such as surface area, value lost due to electrical outages, and registered air transport); and the capacity for USAID’s overseas programs to augment FSO staffing by hiring employees from the local workforce (measured by factors such as literacy rate, mean years of schooling, and education expenditures).

Using a Workforce Planning Model to Address Current Government Requirements

To date, USAID has leveraged the CWPM primarily to identify and address workforce gaps and allocate staffing resources rationally and effectively. However, agencies can use workforce models for a variety of purposes. For example, managers can use a model to understand and weigh the risks and benefits associated with staffing reductions, which is particularly critical in a tight budget environment. A model that ties staffing to expected outcomes and production can help managers assess the impact of staff cuts on the organization’s ability to continue meeting mission requirements, offering data-driven insight into key questions such as: Can we do more with less? Do the fiscal benefits of a staffing reduction outweigh the costs due to production loss?

In addition to risk assessment, an effective model can be used to identify and implement process improvements and efficiencies. Workforce planning is an iterative process; workload and staffing ratios aren’t static. Instead, they must be continually updated and refined to reflect the changing nature of how an organization operates, improving over time as additional process efficiencies are introduced. Workforce planners, who routinely study and quantify the impact of these efficiencies, are thus well-positioned to help identify and institute these process improvements across the organization.

Finally, not only do workforce planning models help managers forecast workload and staffing in terms of quantity, but they are also valuable tools for identifying and understanding staffing profiles in terms of staffing mix. Specifically, models can tie staffing to cost and other sourcing considerations (e.g., the inherently governmental nature of the work, the variability of the work, whether there is a long-term need for the function), allowing managers to evaluate various sourcing scenarios and optimize the organization’s mix of contractor and direct-hire staff. In this way, a workforce planning model can help organizations answer the administration’s charge to better understand and manage the inherent complexity of the federal government’s multisector workforce.

Whether it’s in the public or private sector, workforce planning is a critical element of success for any organization. The CWPM has helped USAID transform its human capital management from a high-risk area to one that that demonstrates that data-driven planning tools can ensure that workforce requirements align with an agency’s strategic goals and budget parameters. The ability to leverage this planning tool to inform recruitment, staff placement, and agency budget planning has better positioned the agency to achieve the primary goal outlined in its human capital strategic plan: “Getting the right people in the right place, doing the right work, at the right time (with knowledge, skills and experience) to pursue U.S. national interests abroad.”

NOTE

1 USAID (2012), Report to Congress on the Development Leadership Initiative, February 2012. Washington, DC.