CHAPTER 2

THE CUSTOMER JOURNEY

2 The customer journey

The customer journey is relevant not only for the service consumer. The service provider must also identify, understand, and master the customer journey. The most successful organizations take this further, endeavouring to put themselves in the place of their customers and experience the end-to-end journey for themselves. Mastering the customer journey helps to maximize stakeholder value through co-creation, focusing on both outcomes and experience. Table 2.1 explains this further.

Table 2.1 The purposes of identifying, understanding, and mastering the customer journey

For the service consumer |

For the service provider | |

Facilitate outcome and experience |

To gain optimal service value and experience from the service relationship To understand what the service consumer needs and desires, not just what the customer states |

To identify and support specific service consumer behaviours and outcomes To optimize and improve products, services, and customer journeys for future value realization |

Optimize risk and compliance |

To ensure key service consumer risks have been identified and addressed |

To focus on the customer satisfaction issues and key areas with the highest pay-outs related to costs |

Optimize resources and minimize costs |

To work together with the service provider to commit and optimize the use of resources during the service lifecycle |

To work together with the service consumer to commit and optimize the use of resources during the service lifecycle To be fair and transparent regarding costs |

The ITIL story: The customer journey

|

Solmaz: As Axle’s business transformation manager, I will help Mariana to create her car share service. We will map and design the customer journey to make sure we are co-creating value with our stakeholders, and building a service that is beneficial to Axle, our users, consumers, and customers. |

|

Mariana: As part of my PhD, I have already been researching how students and staff currently travel and what their experience is like. I have held extensive conversations with people who use car-pooling and car-sharing. I also tested out car-pooling myself as a customer. |

2.1 Stakeholder aspirations

It is important to understand stakeholder value, which requires exploring the functional, social, and emotional dimensions that explain why stakeholders make certain choices, in order to understand why stakeholders need certain products and services.

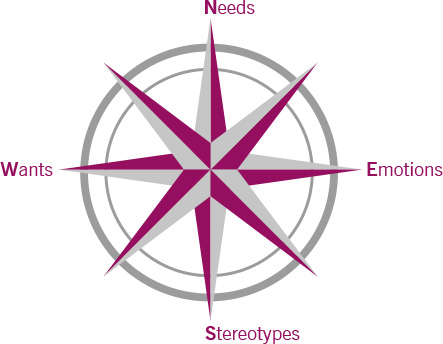

The Disney Institute compass model

The Disney Institute compass model,3 shown in Figure 2.1, may be a helpful tool in identifying the needs, desires, and emotional mindsets of stakeholders.

Figure 2.1 The Disney Institute compass model

The Disney Institute compass model includes four considerations:

• Needs The basic reasons causing the stakeholder to begin the journey. Needs define the outcomes that are relevant to a stakeholder.

• Wants Less definitive than needs, these are the things that stakeholders would prefer to have or that would improve their experiences. Needs are requirements, but fulfilling wants is how service providers exceed expectations.

• Stereotypes The preconceived notions, positive or negative, that stakeholders have about the experience. It is important to consider aspects such as history and culture when designing the journey.

• Emotions Emotional intelligence and behavioural psychology are keys to understanding and mastering the emotional aspect of the journey. A stakeholder’s emotional state will fundamentally affect their experience.

When the drivers are understood and a stakeholder experience aspiration has been defined, the next stage is to identify, understand, and master the end-to-end experience of the customer journey by defining personas, scenarios, journey maps, and service blueprints. Figure 2.2 shows the stages involved in designing end-to-end customer journeys and experiences.

Figure 2.2 The stages involved in designing end-to-end customer journeys and experiences

The ITIL story: Stakeholder aspirations

|

Mariana: From my PhD research, I already know that students and staff aspire to the kind of flexibility and freedom that car ownership provides, but without the costs. Their aspirations are based on: • needing a way to get to and from the campus in São Paulo • wanting a convenient, affordable, and reliable commute, as well as the freedom to travel at different times, or by different routes • stereotypical views that car hire is expensive, and rental periods are inflexible • wanting to make a positive contribution to environmental sustainability by using electric cars instead of traditional cars. |

|

Tomas: For the other stakeholders (primarily Axle and the university), their aspirations are centred on: • using environmentally responsible services • helping students to maximize their time • providing students with equal opportunities to reach campus, regardless of location or socio-economic status • developing a campus community. |

2.2 Touchpoints and service interactions

Every customer journey involves several touchpoints and service interactions between the service provider, service consumer, and other stakeholders.

Definitions

• Touchpoint Any event where a service consumer or potential service consumer has an encounter with the service provider and/or its products and resources.

• Service interaction A reciprocal action between a service provider and a service consumer that co-creates value.

Service interactions include:

• transfer of goods

• provision of access to resources

• interaction with service provider resources (such as a laptop or an Internet of Things [IoT] device)

• joint service actions.

Touchpoints and service interactions are not necessarily the same. A user may be in contact with a service provider resource, such as a working space, a television commercial, or a poster, without interacting with the service provider. In another scenario, a customer may enter into an interaction with a service provider through a third party without being in direct contact with the service provider. Both situations are part of the customer journey and may influence the service experience and outcome.

The customer journey rarely follows a pre-defined path between touchpoints and service interactions. Some journeys may follow a simple, well-defined, and logical path, but most journeys are more complicated and develop from prior situations and transitions, or follow a complex pattern and emerge dynamically along the way. Nevertheless, identifying, understanding, and managing potential touchpoints and service interactions is key to understanding consumer experiences.

Identifying touchpoints and service interactions can be done by listing all of the places and times that the service consumer may encounter the service provider, its products, or its brand. However, individual touchpoints may perform well even if the overall experience is poor. Customers perceive the end-to-end experience, not the individual touchpoints. Hence, to facilitate service consumer satisfaction, each touchpoint must lead to a good experience and the journey as a whole must meet the service consumers’ expectations.

The ITIL story: Touchpoints and service interactions

|

Mariana: Examples of service interactions for eCampus Car Share include customers making a booking, using a vehicle for a journey, and receiving roadside assistance if their vehicle breaks down. |

|

Tomas: All of these interactions represent touchpoints with customers, but Mariana must also be aware that the service has other touchpoints that do not involve a service interaction. An example of this would be a customer seeing an advertisement for the service. |

|

Mariana: Axle and eCampus Car Share do not provide roadside assistance directly, but if it is needed it becomes an important interaction from the perspective of the customer. |

|

Tomas: Even though roadside assistance is provided by Axle’s partner, it is a part of the service offered by eCampus Car Share and it is important that it is included in the user journey map. |

2.3 Mapping the customer journey

A journey is a specific, discrete experience in a service consumer lifecycle. For example, the act of subscribing to a virtual server from a public cloud service provider is a touchpoint within a customer’s journey. Researching and then subscribing to the service, integrating it, and getting it up and running in the service consumer’s organization would constitute the full journey as the service consumer sees it.

Commonly, service providers receive high touchpoint satisfaction scores and low end-to-end journey scores. This is because the individuals and teams managing touchpoints and service interactions can lose sight of the service consumer’s needs and desires. This is most common in multi-channel environments. The numerous customer interaction points across channels, devices, applications, and more, mean that facilitating consistent services and experiences across channels is difficult. This problem can be mitigated if the journey is managed as a whole, rather than through isolated touchpoints.

Touchpoint and service interaction management and thinking should not be abandoned; the expertise, efficiencies, and insights that individual roles and teams contribute are important, and touchpoints and service interactions represent invaluable sources of insights. Instead, in addition to identifying, understanding, and improving individual touchpoints and service interactions, the entire customer journey and service experience should be mapped and analysed.

A customer journey map visualizes the service consumer’s experience. It communicates the journey and the customer’s experiences at every stage. It identifies key service interactions and, for each of these, motivations and questions.

A customer journey map’s objective is teaching organizations about their stakeholders. When mapping a customer journey, it is important to consider the organization’s stakeholders, the journey’s timeframe, channels (telephone, email, portals, service catalogues, in-app messages, social media, forums, and recommendations), and actions that happen before, during, and after the experience of a product or service.

Each end-to-end experience that a customer has with one or more service providers represents a separate customer journey. Mapping individual customer journeys is unfeasible. Therefore, customer journey maps normally represent a generic flow for a group of stakeholders to allow the service provider to focus its efforts on widespread improvements.

Personas4 are often used to represent a group of customers. Personas summarize key characteristics for one or more individuals who exhibit similar attitudes, goals, and behaviours in relation to a service and a service provider. When discussing broad categories of service consumers, ranges must be used in order to summarize attributes of the entire group. These statistics are often too impersonal and difficult to remember when designing the customer journey. In contrast, a persona is a singular user derived from the data range to highlight specific details and important features of the group.

Definition: Persona

A fictitious yet realistic description of a typical or target customer or user of a service or product.

Although personas are archetypes, not actual people, they should be described as if they were real. They are snapshots of relevant and shared characteristics in a customer group, based on user research. To avoid creating bias, it is important to focus on developing generic attributes and relevant characteristics that are related to the use of the service.

It is important to note that customers and users may not be humans. For example, machine-to-machine services may be used by microservices or cognitive technologies. In these cases, the feeling and motivation aspects of the customer journey have little or no relevance.

The ITIL story: Personas – meet Katrina

|

Mariana: We developed several personas. We looked at our existing data and then we trained a small team of researchers to conduct interviews with potential customers and identify trends. |

|

Tomas: Our personas revealed that potential customers are very tech-savvy and have access to mobile devices and data connections at home, while commuting, and on campus. Our first persona is Katrina. |

|

Katrina: I am an international student from Australia, studying for my Masters in languages, in Brazil. I need an affordable way to travel, relax, meet new friends, and be inspired. The following is a brief summary of who I am, what I do, and what is important to me: • Responsibilities I attend classes and supervisor meetings, conduct research, work part-time at a coffee shop, and play team sport. • Goals To successfully complete my Masters; network with students and faculty in my chosen field; explore Brazil’s culture and natural beauty. • Needs To spend class time and face-to-face time with fellow students and faculty; get to campus and the coffee shop on time; reduce unproductive time spent commuting. • Family I have no dependants. My family is back home in Australia, and I am the youngest in a family of six. • Typical day’s activities I wake up early to go to the gym, then head to campus every weekday. I spend most of my day researching, before heading home to study. I work in the coffee shop at weekends. • Difficulties Getting around São Paulo. I do not own a vehicle, and I rely heavily on public transport, which can be time-consuming. Time spent in traffic congestion could be better spent studying. • Touchpoints I know someone in a nearby suburb I can call for a lift. • Constraints There is a limited number of people I can call to car-pool. I am never sure of driver availability, and it is not close to convenient public transport. • Communication Phone, email, text messaging, social media. • Online behaviour My lifeline is social media. I am tech-savvy and quickly adapt to new applications and solutions. I am interested in trying new and exciting digital services. • What I am looking for New experiences or adventures. Travel experience, including music and sporting festivals. • What influences me Friends and colleagues; online blogs, articles, and marketing. • Hopes and dreams To travel the world, and to have flexibility to pack up and go where I please without having to worry about finances. |

Scenarios are short stories about personas trying to achieve their goals by using the service or product in their contexts. Therefore, customer scenarios are specific to customer segments and contexts.

Good scenarios are concise and answer the following questions:

• Who is the user?

• Why does the service consumer want the service?

• What goals does the service consumer have?

• How can the service consumer achieve its goals?

A typical customer journey map standardizes different customer segments. Using a scenario-based approach, it is possible to identify ideal experiences for the scenarios that are most important to the different customer segments. Then the different experiences can be combined to create a high-level customer journey map that is applicable to all.

The ITIL story: Scenarios

|

Tomas: We will use our customer personas to identify scenarios which show how the car share service will help people achieve their goals. Mariana and I collaborated with Solmaz and Radhika from Axle Car Hire to come up with some likely scenarios for our personas. |

|

Mariana: We decided to use Katrina, our international student who enjoys music festivals. We created a setting where Katrina has taken a weekend off work, and offers to drive some friends to a music festival in São Paulo to see her favourite band. Her first goal is to book a car to get to the festival, so that became our first scenario. Later scenarios include collecting the car, researching the locations of public charging stations, parking the car at the festival, and returning the car at the end of the weekend. |

|

Radhika: In the first scenario, our Katrina persona represents a customer segment that includes students who want to travel outside the city on weekends. |

|

Mariana: Katrina logs into the Axle booking app to identify an available car on campus. She selects a van that can accommodate enough people and makes a booking for the weekend. |

|

Tomas: These scenarios, and the experiences they involve, can be combined to create a customer journey map. |

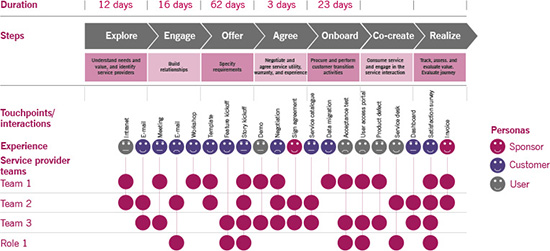

There are many ways to visualize the customer journey. Simple maps typically include the steps of the journey, duration, touchpoints and service interactions, personas, service experience, and service provider teams and roles who interact with the service consumer. Figure 2.3 shows an example of a customer journey map.

Figure 2.3 Example of a customer journey map

Attributes such as service consumer goals, service provider goals, products and product features, channels, environmental properties, data sources (analytics, tracking data, customer relationship management [CRM] data), moments of truth, and prior improvements, may be added to the map for each step depending on the purpose, complexity, and nature of the customer journey. If necessary, some attributes can be categorized into sub-attributes. For example, it is common to map experience by tracking emotions, thoughts, and reactions.

Several techniques and models can be leveraged when mapping customer journeys. A simple but useful example is the Customer Journey Canvas.5 Furthermore, there are many software tools available to visualize personas, stakeholder maps, scenarios, and customer journey maps, including storyboards, emotional journeys, service blueprints, and many more.

The ITIL story: Customer journey maps

|

Mariana: Our first customer journey map will visualize the customer experience from the decision to book a car through to returning the car to campus for recharging after successful completion of the car hire. Customer journey maps generally include seven steps: explore, engage, offer, agree, onboard, co-create, and realize. |

2.3.4 Understanding the customer experience

The customer journey map is a good starting point when attempting to understand the customer experience. However, customer experience is shaped not only by the contact between the service provider and the service consumer, but also by factors that are partly or completely outside the service provider’s influence. Aspects such as organizational branding and the environment (including the digital environment) also influence the customer experience. Additionally, customer experience is affected by periods with no interaction between the customer and the service provider.

One way to gain a greater understanding of the customer experience is to run customer feedback surveys at major touchpoints or utilize customer experience management software. Feedback should reflect the individual customer journey touchpoints and service interactions and also examine brand touchpoints and environmental conditions, including their impact on comfort, ease, and speed.

The following questions should be asked when examining customer experience:

• What is the customer doing during each step?

• What encourages or discourages the customer from moving to the next step?

• What emotions do each of the steps trigger?

• Does the customer have questions that are difficult to find answers to?

• In which contexts does the customer get anxious?

• Could uncertainties cause the customer to give up and find a different service provider?

• What kind of obstacles does the customer confront in each stage?

• What are the cost and risk factors?

The service provider cannot understand the customer experience without involving the service consumer in its analysis.

If we apply the Johari window, which was proposed by psychologists Joseph Luft and Harrington Ingham (Luft and Ingham, 1955) and is shown in Figure 2.4, to the service relationship, it becomes evident that some areas are unknown to the service provider but known to the service consumer. Therefore, the service provider must seek feedback on behaviour in the invisible areas of the service relationship. Likewise, there are areas that are known only to the service provider, but that would benefit the customer experience if the service consumer was aware of them. These areas should be disclosed to the service consumer by the service provider.

Figure 2.4 The Johari window

Adapted with permission from Luft (1969), used by permission of MindTools

The customer journey map is about listening to what the customers are saying, understanding their motives, and, when applicable, systematically measuring their opinions and actions and integrating this information into continuous feedback.

The ITIL story: Mapping the customer journey

|

Mariana: Our customer journey map will visualize the end-to-end touchpoints and service interactions. These will range from how our customers find us, through to booking, collection, use, and return of the car, and collection of customer satisfaction feedback. |

2.4 Designing the customer journey

The overall objective for the customer journey should be to plan and design customer journeys that support optimal value co-creation and lead to outstanding customer experiences.

Customer journey design is part of service design. However, customer journeys may span multiple services or products, and single services or products may support multiple customer journeys. More about service and product design can be found in Chapter 5 and in the service design practice guide.

‘Service design helps to innovate (create new) or improve (existing) services to make them more useful, usable, desirable for clients and efficient as well as effective for organizations. It is a holistic, multi-disciplinary, integrative field (Moritz, 2005).’

Before designing the actual customer journey, the desired outcome and customer and user experience should be defined. The expected value from the journey and how each stage can contribute to the co-creation of value should be considered as part of this definition. As was outlined in Chapter 1, the value definition includes:

• outcome

• experience (how the journey, services, products, brand, and environment are perceived and make the customer or user feel)

• utility

• warranty (including availability, performance, capacity, information security, continuity, accessibility, and usability)

• risk and compliance

• cost and resources.

The desired value should be defined for each major stakeholder in the customer journey. Techniques for defining, measuring, optimizing, and communicating value are described in the following chapters.6

Design thinking is a method that puts the user at the centre of the design process. It addresses how designers should think in order to create innovative solutions that fit user needs. For good innovation to occur, designers need to engage with real users to truly understand their problems and explore different ideas for a resolution. The main idea of the method is to explore and gather feedback from real users.

At a high level, Marc Stickdorn’s five principles of service design thinking may be adopted to guide the design process (Schneider and Stickdorn, 2012):

• User-centred The customers and users need to be put at the centre of the design process. This requires a genuine understanding of the customers and users beyond statistical descriptions and empirical analyses of their needs.

• Co-creative Facilitating co-creation in groups representative of the stakeholders is a vital aspect of design thinking and a fundamental part of service design. All stakeholders should be included in the design process.

• Sequencing Service design thinking deconstructs customer journeys into single touchpoints and service interactions. These, when combined, create service moments. Touchpoints and service interactions take place human-to-human, human-to-machine, and even machine-to-machine, but also occur indirectly through third-party feedback, such as online reviews. Every customer journey follows a three-step transition of pre-service period (getting in touch with a service), the actual service period (when the service consumers experience a service), and the post-service period. The customer journey should be visualized as a sequence of interrelated actions.

• Evidencing Physical evidence or artefacts, such as souvenirs, can trigger the memory of positive service moments. Therefore, through emotional association, they can continue to enhance a customer’s experience. Service evidence can prolong service experiences beyond the actual service period far into the post-service period. Also, service evidencing can help reveal inconspicuous backstage services. Intangible services should therefore be visualized in terms of physical artefacts.

• Holistic We see, hear, smell, touch, taste, and emotionally feel the physical manifestation of services. The entire environment of a customer journey, service, or product should be considered, as should alternative customer journeys.

At a more practical level, customer journey design does not differ much from other design processes. Although design processes are non-linear, it is possible to articulate an outline structure. It is important to understand that this structure is iterative in its approach. A typical customer journey design process may include the stages proposed by the Hasso Plattner Institute of Design at Stanford, which are:

• Empathize Learn about the stakeholders that you are designing for. Understand the human needs involved. Define and test personas and scenarios. Set aside your own assumptions about the world in order to gain insight into the stakeholders and their needs.

• Define Construct a point of view that is based on user needs and insights. Re-frame and define the problem in human-centric ways. Map the existing customer journey, if any, and map stakeholder experiences to identify any problems in the customer journey. Define and plan for the desired outcome, experience, and value. Set goals and define metrics.

• Ideate Brainstorm and come up with creative solutions. Create many ideas in ideation sessions to think of improvements to the customer journey. By the end of this phase, the team should have several problem-solving ideas.

• Prototype Build a representation of one or more of your ideas to show to others. Adopt a hands-on approach in prototyping. Design customer journey maps and service blueprints.

Design for the stakeholders’ mental models by asking them to structure the journey or products for you. Consider frequency, sequence, and importance. Frequency means that things the customers do most frequently should have a prominent position in the sequence. Sequence means that activities that occur in sequence should be presented in sequence. Importance means that important pieces of information need to be given clearly and at the right time. Understanding the customers’ mental model and applying the frequency, sequence, and importance rule will solve most of the stakeholders’ usability needs. Verify that the design helps deliver the planned outcome, experience, and value.

• Test Return to the original stakeholder group and test your ideas for feedback. Do not avoid mistakes but explore as many mistakes as possible. Perform usability testing, role plays, and A/B testing. Track usage, build in feedback loops, review metrics, and role play to test that the design helps to deliver the planned outcome, experience, and value.

The customer journey design process involves knowledge and capabilities from different fields of expertise, including product design, graphic design, interaction design, social design, and design ethnography. Representatives from these fields may be involved in designing and planning customer journeys.

Additionally, there is a variety of tools and techniques available for customer journey design, including stakeholder maps, contextual interviews, five whys, day in the life, expectation maps, personas, storyboards, prototyping, A/B testing, storytelling, service blueprints, and operating model canvas. (For a good introduction to most of the listed tools, see Schneider and Stickdorn, 2012.)

2.4.2 Leveraging behavioural psychology

Humans are often rational beings, but can behave irrationally. However, we are predictably irrational (Ariely, 2008). Therefore, the design of customer journeys involving humans should cater for logical or rational behaviour and incorporate knowledge of cognitive biases and intuitive behaviour. Emotional intelligence and behavioural psychology are the keys to understanding and mastering the emotional aspect of the journey.

A cognitive bias is a systematic pattern of deviating from rationality when making a judgement. An evolving list of cognitive biases has been identified over decades of research in cognitive science, social psychology, and behavioural economics. Examples of well-established cognitive biases are:

• Peak-end bias The tendency that we do not seem to perceive experience as a whole, but the average of how it was at its peak. So, after using a product or service, we tend to disproportionately recall the high and low points of the customer journey and not all the individual aspects of it. In particular, unpleasant endings have a strong negative impact.

• Availability bias The tendency to base our judgements on events that are most available in our memory, despite the fact that the availability of a memory is often influenced by unique and emotional factors. For example, the distribution and frequency of positive and negative points of interaction during the customer journey affects our service perception.

• Loss aversion The pain of giving up something is greater than the utility associated with obtaining it. We want to be in control of our journey as well as other immediate aspects of our life affected by the customer journey.

By understanding these cognitive biases, it is possible not only to consider them, but also to take advantage of them in the design of the customer journey (Bhattacharjee et al., 2016), including by:

• working through bad experiences early so that service consumers remember the more positive elements of the interaction

• segmenting pleasure and combining pain for the service consumers so that the pleasant parts of the journey form a stronger part of consumers’ recollections

• finishing on a strong, positive note, as the service consumers’ final interactions will have a disproportionate impact on their memory of the service

• providing service consumers with choices to give them a sense of control

• preventing surprises to increase service consumer satisfaction with the services received.

Redesigning the entire journey to incorporate the principles of behavioural psychology has the potential to yield sustained improvements in service consumer satisfaction. (Kahneman, 2011 gives a good introduction to biases and behavioural design.)

2.4.3 Design for different cultures

Definitions

• Mental model An explanation of someone’s understanding of how something works in the surrounding world.

• Culture A set of values that is shared by a group of people, including expectations about how people should behave and their ideas, beliefs, and practices.

‘Mental models help an individual’s orientation in the world; they are the abstract and reductive mental representation of the complexity all of us face in everyday life – the schemas by which all of us understand the world around ourselves (Schneider and Stickdorn, 2012).’

Stereotypes are part of the mental model. Geert Hofstede says that culture is the collective mental programming of the human mind which distinguishes one group of people from another. Therefore, culture is part of the mental model and should be considered when designing customer journeys for different cultural groups or personas. Some examples are:

• users from different countries

• customers from different industries

• users from different teams in an organization

• users from different professions

• sponsors from public organizations.

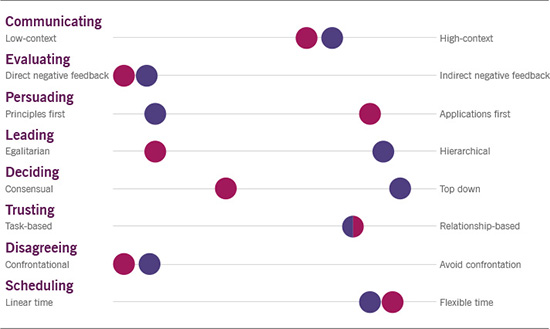

Culture maps are tools which map cultures to decode the influences of intercultural collaboration. They are useful for analysing and designing service consumer scenarios as a basis for customer journey design. Figure 2.5 shows the culture of two user groups mapped to eight dimensions to identify similarities and differences. In this figure, each dimension is represented as a scale or spectrum of opposite extremes (Meyer, 2014).

Figure 2.5 The eight dimensions of culture

The ITIL story: Designing the customer journey

|

Tomas: Visualizing the customer journey enables Mariana to create an exceptional customer experience for students and staff, not only providing value for them, but ensuring that value is created for Axle Car Hire. |

|

Radhika: At Axle, we want to expand our service, develop brand recognition in the marketplace, and make enough revenue to re-invest in community initiatives. |

|

Mariana: Without design thinking philosophy and processes, it is possible to miss things that could impact the customer experience. For example, most of our customers are not frequent drivers, so they can be nervous about driving in city areas, especially if they are driving a vehicle they are not familiar with. |

|

Tomas: Because our campus is in the city, we can enhance the customer journey by providing access to instructional videos on city routes and up-to-date information about traffic flow and congestion. |

|

Mariana: A bad traffic experience can negatively bias our customers against using our car share service, even though Axle and eCampus Car Share have no control over traffic conditions. |

|

Solmaz: When designing the customer journey, we returned to our research for an understanding of the different cultures on campus. We know that the university has a large population of local and international students and staff, and that they also differ in their age ranges and socio-economic backgrounds. |

|

Radhika: Our research in São Paulo has discovered that older people regard car ownership as being more prestigious than younger people do. Many staff members on campus are part of this older generation, so when we design our customer journey, we will include ways to target this group to make car-sharing more desirable. |

2.5 Measuring and improving the customer journey

Customer satisfaction is a moving target. To continually improve, it is important to measure customer experience and feedback and gather analytics about stakeholder behaviour both across the journey and at individual touchpoints and service interactions.

Additionally, indirect measures, such as service quality, product quality, and the quality of the enabling value streams, practices, and resources can highlight customer experience and satisfaction.

It is best practice to start at the top, with a metric to measure the customer experience, and then cascade downwards into their key customer journeys and indirect performance and output indicators.

There are always more opportunities for improvement than there are resources. Therefore, the focus should be on quality and customer experience opportunities with the best chance of a high return on investment (ROI). Gaps in the journey and opportunities to improve it should be prioritized. Although eliminating pain points for customers is important, it is equally critical to identify areas that can differentiate an organization from competitors as customer expectations change.

Problem management techniques should be used to isolate the causes of gaps and identify improvements to all levels of the service stack: customer journey, service and product design, underpinning value streams, practices, and resources that enable the value streams and services.

The ITIL story: Measuring and improving the customer journey

|

Mariana: Before we launch the eCampus Car Share service, we will develop feedback forms that we can send to customers after key touchpoints. We will use these to learn about their experience of the booking, collection, and return of the cars, as well as their experience of the charging stations and other service offerings, such as the instructional videos and traffic updates. We will use these findings and insights to measure and continually improve the customer journey. |

|

Tomas: Mariana should not wait until the end of the customer journey to collect feedback. She needs to understand what the customer is experiencing as they are experiencing it. For example, booking a vehicle might be an arduous process, but returning it might be simpler. A single survey at the end of the customer journey might not pick up on the earlier touchpoint, and the customer might forget to communicate about the pain point upfront. Without that insight, Mariana will not know how to improve the booking process. |

2.6 Summary

Each service consumer is different and should be treated differently. Personas summarize key characteristics for customer and user archetypes and help the service provider to understand their needs and aspirations. By following the personas on their journey from touchpoint to touchpoint towards service outcome, a service provider can understand the customer experience. Leveraging this insight, combined with design thinking, behavioural psychology, and cultural insight, the service provider will be able to design and master customer journeys that lead to unique customer outcomes and experiences.

The ITIL story: Summary

|

Mariana: Now that we have a deep understanding of the customer experience, we feel ready to launch our eCampus Car Share service for students and staff. |