5 Service strategy, governance, architecture and ITSM implementation strategies

The purpose of this chapter is to explore various aspects of service strategy as they relate to the business, and the overall implementation of IT service management (ITSM). Specifically, it will provide an overview of corporate governance of IT, a service management system, the relationship between ITSM and enterprise architecture and the relationship between ITSM and application development.

Chapters 3 and 4 cover the concepts and processes of service strategy in detail, but they do not explain an ITSM implementation strategy – or how to go about implementing the ITSM processes described in the core ITIL publications. This chapter will provide an overview of what such an implementation strategy could look like.

5.1 GOVERNANCE

Governance is the single overarching area that ties IT and the business together, and services are one way of ensuring that the organization is able to execute that governance. Governance is what defines the common directions, policies and rules that both the business and IT use to conduct business.

Many IT service management strategies fail because they try to build a structure or processes according to how they would like the organization to work instead of working within the existing governance structures.

Changing the organization to meet evolving business requirements is a positive move, but project sponsors have to ensure that governance of the organizations recognizes and accepts these changes. Failure to do this will result in a break between the organization’s governance policies and its actual processes and structure. This results in a dysfunctional organization, and a solution that will ultimately fail.

5.1.1 What is governance?

Corporate governance refers to the rules, policies and processes (and in some cases, laws) by which businesses are operated, regulated and controlled. These are often defined by a board of directors or shareholders, or the constitution of the organization; but they can also be defined by legislation, regulation, standards bodies or consumer groups.

Governance is important in the context of service strategy, since the strategy of the organization forms a foundation for how that organization is governed and managed.

The standard for corporate governance of IT is ISO/IEC 38500. This publication references the concepts of this standard and how it has been applied.

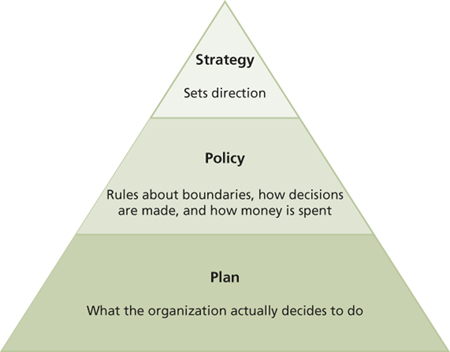

Governance is expressed in a set of strategies, policies and plans, as illustrated in Figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1 Strategy, policy and plan

Figure 5.1 shows how governance works to apply a consistently managed approach at all levels of the organization – firstly by ensuring a clear strategy is set, then by defining the policies whereby the strategy will be achieved. The policies also define boundaries, or what the organization may not do as part of its operations. For example, stating that IT services will be delivered to internal business units only, and will not be sold externally as an outsourcing company would. The policies also clearly identify the authority structures of the organization. This is indicated in how decisions are made, and what the limits of decision-making will be for each level of management. The plans ensure that the strategy can be achieved within the boundaries of the policies.

It should be noted here that, while plans are ultimately part of governance, governors themselves do not define or produce the plans themselves. Rather, managers will use governance to define plans that are consistent with, and approved by, the executive and governors. However, governors will review the progress and implementation of plans.

5.1.1.1 Setting the strategy, policies and plans

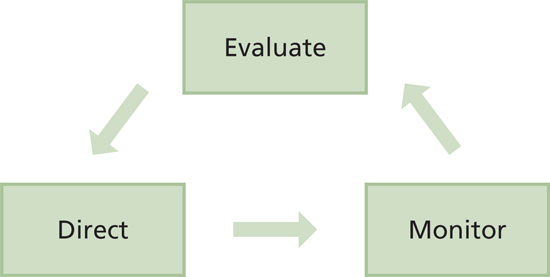

Defining strategy, policies and plans is a rigorous process, and consists of three main activities: evaluation, directing and monitoring. Although the governance process itself is out of the scope of this publication, it is helpful to provide an overview, and to demonstrate the links between service strategy and governance. Figure 5.2 highlights the main activities of governance.

Figure 5.2 Governance activities

Governance needs to be able to evaluate, direct and monitor the strategy, policies and plans. These activities can be summarized as follows.

5.1.1.2 Evaluate

This refers to the ongoing evaluation of the organization’s performance and its environment. This evaluation will include an intimate knowledge of the industry, its trends, regulatory environment and the markets the organization serves. The strategic assessment (section 4.1.5.1) is typical of the type of input that is used in this evaluation.

Items that are used to evaluate the organization include:

![]() Financial performance

Financial performance

![]() Service and project portfolios

Service and project portfolios

![]() Ongoing operations

Ongoing operations

![]() Escalations

Escalations

![]() Opportunities and threats

Opportunities and threats

![]() Proposals from managers, shareholders, customers etc.

Proposals from managers, shareholders, customers etc.

![]() Contracts

Contracts

![]() Feedback from users, customers and partners.

Feedback from users, customers and partners.

5.1.1.3 Direct

This activity relates to communicating the strategy, policies and plans to, and through, management. It also ensures that management is given the appropriate guidelines to be able to comply with governance.

This activity includes:

![]() Delegation of authority and responsibility

Delegation of authority and responsibility

![]() Steering committees to communicate with management, and to discuss feedback (also used during ‘evaluate’)

Steering committees to communicate with management, and to discuss feedback (also used during ‘evaluate’)

![]() Vision, strategies and policies are communicated to managers, who are expected to communicate and comply with them

Vision, strategies and policies are communicated to managers, who are expected to communicate and comply with them

![]() Decisions that have been escalated to management, or where governance is not clear.

Decisions that have been escalated to management, or where governance is not clear.

5.1.1.4 Monitor

In this activity, the governors of the organization are able to determine whether governance is being fulfilled effectively, and whether there are any exceptions. This enables them to take action to rectify the situation, and also provides input to further evaluate the effectiveness of current governance measures.

Monitoring requires the following areas to be established:

![]() A measurement system, often a balanced scorecard

A measurement system, often a balanced scorecard

![]() Key performance indicators

Key performance indicators

![]() Risk assessment

Risk assessment

![]() Compliance audit

Compliance audit

![]() Capability analysis, which will ensure that management has what they need to comply with governance.

Capability analysis, which will ensure that management has what they need to comply with governance.

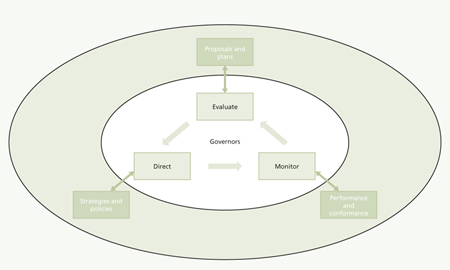

5.1.2 Who governs?

In this section the term ‘governor’ refers to any person or group that is responsible for the governance of an organization. In some organizations this could be a board of directors, appointed by the shareholders or members of the organization specifically to ensure that the organization fulfils its mission. In government organizations these might be senior officials (e.g. cabinet ministers or secretaries), or a legislative or executive body (e.g. Congress, Houses of Parliament, Department of Public Administration etc.).

‘The executive’ refers to the group of senior managers of the organization that is responsible for the day-to-day governance of the organization on behalf of the governors. The executive, generally led by the chief executive officer (CEO), provides the link between the governors and the managers of the organization. Members of the executive have both a governance and management role, and are an overlap or an intersection of the two, specifically so that the terms of governance can be translated into what needs to be done to fulfil and comply with governance.

5.1.3 What is the difference between governance and management?

Governance is performed by governors. Governors are concerned with ensuring that the organization adheres to rules and policies; but even more, that the desired end results are being achieved in doing so.

Management is performed by executives and people who report to them. Their job is to execute the rules, processes and operations of the organization according to the governance policies, and to achieve the strategies defined by the governors. Managers coordinate and control the work that is required to meet the strategy, within the defined policies and rules. The executive ensures that governance and management are aligned and that management is executing the right activities in the right way, as required by governance.

Governors (those who create and ensure governance) are often not managers in the same organization. Governance and accountability are created by the governors. Management is the execution of the rules and authority granted by governance. This enables a system of checks and balances to be maintained and thus maximizes the integrity of the organization. Exceptions include situations where the chairperson (governor) of the board is also the chief executive officer or managing director (manager).

Figure 5.3 shows the role of managers relative to the activities of governance.

Figure 5.3 Governance and management activities

The governance of IT service management will generally be determined by people with management responsibility in the organization. For example, it is important to determine how processes and functions are managed, and how they relate to one another, especially in terms of who is accountable and responsible for each area. However, it is important to remember that service strategies, and strategies for organizing service management, should be a subset of the overall strategies, policies and plans defined above.

5.1.4 The governance framework

A governance framework is a categorized and structured set of documents that clearly articulate the strategy, policies and plans of the organization. ISO/IEC 38500 outlines the following six principles that are used to define domains of governance (or areas that need to be governed):

![]() Establish responsibilities

Establish responsibilities

![]() Strategy to set and meet the organization’s objectives

Strategy to set and meet the organization’s objectives

![]() Acquire for valid reasons

Acquire for valid reasons

![]() Ensure performance when required

Ensure performance when required

![]() Ensure conformance with rules

Ensure conformance with rules

![]() Ensure respect for human factors.

Ensure respect for human factors.

Each of these domains will have high-level policies that form part of the framework, and which will be used by managers to build procedures, services and operations that meet the organization’s objectives.

5.1.5 What is IT governance?

IT governance does not exist as a separate area. Since IT is part of the organization, it cannot be governed in a different way from the rest of the organization. ISO/IEC 38500 refers to ‘corporate governance of IT’ and not IT governance. This implies that IT complies with and fulfils the policies and rules of the organization, and does not create a separate set for itself.

As mentioned several times in this publication, IT and the other business units share the same objectives and corporate identity and are required to follow the same governance rules.

What is normally called IT governance is usually a matter of the CIO, or senior IT manager, enforcing corporate governance through a set of applied strategies, policies and plans. Nevertheless, as a member of the executive, the CIO participates in how governance is defined and translated for management.

5.1.6 How is corporate governance of IT defined, fulfilled and enforced?

Although IT governance is not separate from corporate governance, it is important that IT executives have input into how corporate governance will specify how IT is governed. This is usually done through an IT steering committee, which also defines IT strategy and is involved in all major decisions regarding IT and its role in the organization.

As a member of the executive of directors, the CIO will ensure that the corporate strategies, policies, rules and plans include a high-level overview of how IT will be governed. If the CIO is not a member of the board of directors, it is the responsibility of the member who is responsible for IT to ensure that the CIO is consulted on what needs to be included.

In most cases, the governors will need assistance in defining governance for IT. This can be provided by management consultants or by engagement with senior IT leaders in the organization. In many organizations, the IT department will be heavily involved in defining governance and may even have a dedicated group to work on defining, enforcing and monitoring governance for IT. It is important to note, however, that the final decision about the strategy, policies, rules and plans and how they are enforced is made by the governors, since they are accountable for governance. This accountability may not be delegated to managers, who are required to comply with governance.

Governance is fulfilled by the leadership of each business unit, including IT. Therefore the CIO is responsible for ensuring that IT operates according to the strategy, policies, rules and plans defined in corporate governance. Since IT is an integral part of each business unit, however, it is important that the leaders of other business units are also engaged in defining how governance of IT will be fulfilled and enforced.

This is usually achieved by establishing an IT steering committee, also called an IT steering group. The purpose of the steering committee is to establish how IT will comply with and fulfil corporate governance. In addition it also represents how IT works with other business units to help them comply with corporate governance.

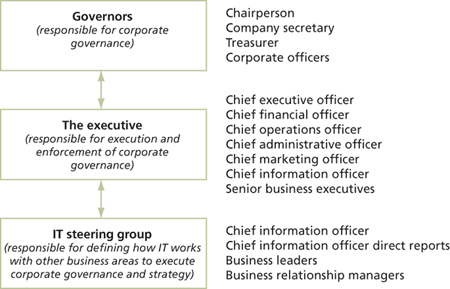

An example of the IT steering group in relation to other governance bodies is shown in Figure 5.4. The names and specific roles of each of these groups may differ from organization to organization.

Figure 5.4 Governance bodies

The composition of the IT steering committee makes it an ideal platform to discuss and agree a number of other areas too. These include:

![]() The discussion and recommendation of the IT strategy, and IT strategy-planning documents, to the governors

The discussion and recommendation of the IT strategy, and IT strategy-planning documents, to the governors

![]() Clarification of strategic requirements from other business units

Clarification of strategic requirements from other business units

![]() Ensuring the contents and consequences of the IT strategy are clearly understood by other business leaders

Ensuring the contents and consequences of the IT strategy are clearly understood by other business leaders

![]() Major decisions requiring funding from other business units

Major decisions requiring funding from other business units

![]() Settling disputes about IT service priorities

Settling disputes about IT service priorities

![]() Reaching agreement about the minimum level of service for shared services (usually when one business unit wants a much higher level of service, but cannot afford to cover the costs themselves, and requires the agreement of all other business units to move to the higher level)

Reaching agreement about the minimum level of service for shared services (usually when one business unit wants a much higher level of service, but cannot afford to cover the costs themselves, and requires the agreement of all other business units to move to the higher level)

![]() Discussing IT service issues that require senior management intervention

Discussing IT service issues that require senior management intervention

![]() Negotiating changes to policies in other business units that impede IT’s ability to meet its objectives (for example, an IT organization is asked to reduce costs, but users insist on the most expensive solution).

Negotiating changes to policies in other business units that impede IT’s ability to meet its objectives (for example, an IT organization is asked to reduce costs, but users insist on the most expensive solution).

5.1.7 How does service strategy relate to governance?

From sections 5.1.1 to 5.1.5 it appears that all strategy is strictly contained within the role of the governors. This is not the case. Instead, the governors are responsible for the strategy of the organization, and for ensuring that all parts of the organization are aligned to that strategy. Every part of the organization must, however, produce its own strategy that enables it to fulfil the overall corporate strategy. Each strategy must be grounded in the corporate strategy and must be approved by the governors.

Section 4.1 covers the process of strategy management for IT services. That section discussed two levels of strategy – service strategy in general, and service strategy for IT as an internal service provider (section 4.1.5.20). In general strategy management is the responsibility of the board of directors. In larger organizations this is performed by a dedicated department reporting to the CEO or managing director – often called the strategy and planning department or something similar.

Strategy management for an internal IT service provider will be overseen by the CIO and the IT steering committee. Again in larger organizations, this might be a dedicated function reporting to the CIO.

The service portfolio is also an integral part of fulfilling governance, since the nature of services, their content and the required investment are directly related to whether the strategy is achievable. The current and planned services in the service portfolio are an important part of strategy analysis and execution.

Financial management for IT services is also a critical element of evaluating what investment is required to execute service strategies, ensuring that strategies are executed within the appropriate costs, and then measuring whether the strategy was achieved within the defined limits.

Demand management provides a mechanism for identifying tolerance levels for effective strategy execution. Each strategy approved by the governors must include the boundaries within which that strategy will be effective. Demand management assists in defining these boundaries in terms of business activity and service performance.

Business relationship management is instrumental in defining the requirements and performance of services to customers. This makes it possible for those customers to comply with corporate governance in their organizations.

5.2 ESTABLISHING AND MAINTAINING A SERVICE MANAGEMENT SYSTEM

Governance works to apply a consistently managed approach at all levels of the organization. Areas of specialization and processes within the organization are managed by management systems.

Definition: management system (taken from ISO 9001)

A system to establish policy and objectives and to achieve those objectives.

A system can be further defined as a set of processes, technology and people working cohesively to achieve a set of common goals. Note that the management system of an organization can include different management systems, such as a quality management system, a financial management system or an environmental management system.

A service management system (SMS) is used to direct and control the service management activities to enable effective implementation and management of the services. Processes are established and continually improved to support delivery of service management.

The SMS includes all service management strategies, policies, objectives, plans, processes, documentation and resources required to deliver services to customers. It also identifies the organizational structure, authorities, roles and responsibilities associated with the oversight of service management processes. For service providers that are aiming to achieve and maintain certification to ISO/IEC 20000, the SMS meets the requirements of ISO/IEC 20000-1. Coordinated integration and implementation of an SMS provides ongoing control, greater effectiveness, efficiency and opportunities for continual improvement.

The adoption of a SMS should be a strategic decision for an organization. The SMS, its processes and the relationships between the processes are implemented in a different way by different service providers. The design and implementation of the SMS will be influenced by the service provider’s needs and objectives, requirements, processes and the size and structure of the organization. The SMS should be scalable. For example, a service provider may start with a simple situation that requires a simple SMS solution. Over time, the service provider may grow and require changes to the SMS, perhaps to cope with different market spaces, the different nature of relationships with customers, organizational changes, new suppliers or changes in technology.

As referenced in Chapter 2, an organization may implement several management systems such as:

![]() A quality management system (ISO 9001)

A quality management system (ISO 9001)

![]() An environmental management system (ISO 14000)

An environmental management system (ISO 14000)

![]() A service management system (ISO/IEC 20000-1)

A service management system (ISO/IEC 20000-1)

![]() An information security management system (ISO/IEC 27001).

An information security management system (ISO/IEC 27001).

As there are common elements between management systems, many organizations manage these systems in an integrated way rather than having separate management systems. To meet the requirements of a specific management system standard an organization needs to analyse the requirements of the relevant management standard in detail; and compare them with those that have already been incorporated in the existing integrated management system.

5.3 IT SERVICE STRATEGY AND THE BUSINESS

This section has been covered to some extent in Chapters 3 and 4, but the components have been summarized and repeated here for ease of reference.

Aligning the IT service strategy with the business is an important exercise that involves both parties. Successful strategies are typically anchored top to bottom in the business vision, mission and core values. The overarching IT service strategy and underpinning service provider strategies should be examined and validated with the business to ensure that they serve the desired business outcome.

When it comes to the overarching business strategy, IT organizations typically are in general alignment with the rest of the business. As the overarching strategy is translated into strategies for individual business units, however, it becomes more difficult to achieve alignment, especially if the business units themselves are fairly autonomous. The level for business unit strategies will vary from organization to organization but it is best to avoid assumptions when it comes to defining these underpinning strategies.

IT service strategy – a strategy within a strategy

An organization may have an IT strategy for service operations, which includes the service desk function. Considering that the service desk is the front-end to service operations, it is vitally important that the strategy clearly articulates what the expectations and desired outcomes of the service desk are. If superior customer service, accountability or customer advocacy are important differentiators for the business, the service desk should be designed, resourced and empowered to make one or more of those a reality.

Examining the IT service strategies at a more detailed level allows for the organization to be ‘fit for purpose’ and ‘fit for use’, which ultimately translates to value in the form of business outcomes.

5.3.1 Using service strategy to achieve balance

Building an overarching IT service strategy that is underpinned by a set of more targeted service strategies can require some careful consideration and planning. It often includes objectively considering a service’s current state, future state, competition, opportunity, risk and, most importantly, talking with the business.

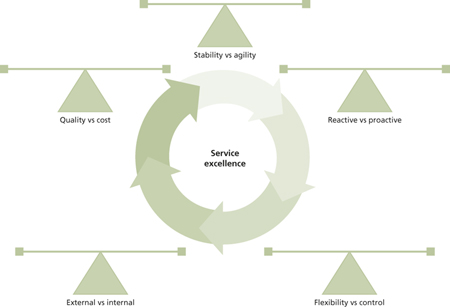

A good assessment of the effectiveness of a given service in supporting the overall business outcome and strategy is to evaluate how it impacts the balance of the organization. These are discussed in detail in ITIL Service Operation (see also Figure 5.5).

This might include a review of current investments, successes, failures, volumes, trends, costs, values etc. Achieving a perfect balance here is not only unlikely; it may be unbalanced by design. For example, the leadership team in a start-up organization may have greater appetite for risk than that of the market leader. Therefore, adjusting the balances should be done intentionally and be fully supported by the business. The service providers cannot lose sight of the overarching IT strategy, their position as an integrated business partner or their role of supporting the overall business vision/mission.

Figure 5.5 Using strategy to achieve balance

5.3.2 Integrated partners

Alignment of IT strategies with the business is something that should be done with the business leaders. IT leadership can contribute intelligence about technology trends, open market services, opportunities, risks and threats but, in the end, the IT strategies should represent the business they serve, and should be understood and agreed to by the business.

One method for creating and evolving these strategies is to create an IT steering committee with representation from the business, IT, enterprise architecture and governance. Examining the business value of IT services and aligning IT strategies helps IT begin to think about services in the context of value creation rather than components, technology and organization. Now IT service providers can begin to retool and think about all of the potential service options rather than just the ones built or provided internally.

IT can begin to transition away from specific technology discussions with the customers to value-based discussions anchored with the desired business outcome. When IT becomes an integrated strategic business partner, it starts to seek out the best possible solution for the business even if that means recommending a service provider other than itself.

5.4 IT SERVICE STRATEGY AND ENTERPRISE ARCHITECTURE

Enterprise architecture refers to the description of an organization’s enterprise and associated components. It describes the organizational relationship with systems, sub-systems and external environments along with the interdependencies that exist between them. Enterprise architecture also describes the relationship with enterprise goals, business functions, business processes, roles, organizational structures, business information, software applications and computer systems – and how each of these interoperate to ensure the viability and growth of the organization.

Service strategy and enterprise architecture are complementary while both serving different purposes in the organization. When examined from a pure framework perspective, there can sometimes appear to be overlapping elements and/or activities. Part of developing a sound strategy is to examine the relevant industry frameworks and fabricate a model that is most likely to position the organization for the greatest degree of success. This isn’t an exercise of choosing one framework over another but it is a case for selecting the components, activities or solutions that best serve the desired outcome. In the end, an organization is likely to be leveraging several industry frameworks, rather than adopting a single specific framework in its entirety.

Put another way, enterprise architecture identifies how to achieve separation of concerns (thus achieving a set of checks and balances), and how to define architectural patterns (or the rules of how systems communicate with one another). See section 5.3.8 in ITIL Service Design for more information on separation of concerns (SoC).

Enterprise architecture injects valuable intelligence into service strategy with clear definitions around business processes and solid engineering design principles. Enterprise architecture also plays a key role in the creation, use, maintenance and modelling of a reusable set of architectures for the organization. These architecture domains might include business architecture, information architecture, technology architecture, governance architecture and others. IT and service strategy development/maintenance should include representation from enterprise architecture to ensure seamless integration and alignment across an organization’s enterprise and associated components. Development and maintenance of this is typically done by the IT steering committee.

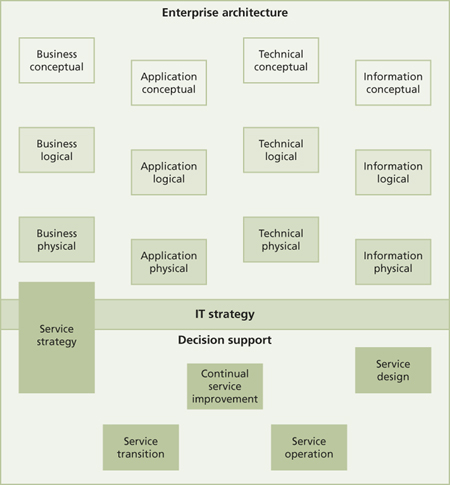

The enterprise architecture team should have established models and criteria for designing services, processes and functions within the enterprise. IT process and function design may require additional detail but there should be a sense of alignment with the overall enterprise. These models are typically designed to be extensible so that new business processes and functions can easily be added, extended or discontinued. The IT service management team can subsequently create a service management implementation model that snaps into the broader enterprise architecture model in the form of decision support.

Figure 5.6 represents a generic open source architecture model that includes four primary architecture layers (business, application, technical, information), which are linked to the underlying decision support elements via the IT strategy. This model may be slightly different depending on the organization’s preferred enterprise architecture framework but the concepts are applicable. Each architecture layer has three different perspectives that represent a conceptual, logical and physical view. The conceptual view represents the ‘What’ or the high-level capabilities of the corresponding architecture layer. The logical view represents ‘How’ the ‘What’ will be achieved, while the physical view represents the specific elements that will enable the ‘How’ and ‘What’ from an architecture perspective. The next layer of the model is the IT strategy, which should underpin the enterprise architecture layers. The IT strategy should fully support the enterprise architecture principles so that IT is effectively acting as a fully integrated business partner. In this model, the ITSM elements act as decision support system for the IT strategy to ensure service decisions, whether they be ‘service portfolio’ or ‘change management’, are fully aligned with the high-level capabilities as defined by the enterprise architecture. In summary, the enterprise architecture, IT strategy and decision support need to be fully integrated to ensure that the desired business outcomes are realized and the associated enterprise architecture systems and sub-systems are optimized. The ITSM processes that make up decision support can serve as a check and balance to minimize drift from the desired business outcome.

Figure 5.6 Enterprise architecture, strategy and service management

The extensibility of this model should include support for both internal and external service providers’ need to develop elementary processes within a given IT function or process. There are many functions that are simply not defined in a single industry framework. Therefore, establishing an extensible model that enables service providers to integrate seamlessly is important and will minimize the number of orphaned processes and functions in the organization. Failure to address this can result in inconsistencies, attempts to fit everything into a single framework and overlapping processes in the organization.

Examples of enterprise architecture frameworks include:

![]() TOGAF The Open Group Architecture Framework, which defines a framework for the design, planning, implementation and governance of an enterprise. TOGAF defines the structure of components in the organization, their relationships with one another and the principles and guidelines governing their design and evolution.

TOGAF The Open Group Architecture Framework, which defines a framework for the design, planning, implementation and governance of an enterprise. TOGAF defines the structure of components in the organization, their relationships with one another and the principles and guidelines governing their design and evolution.

![]() The Zachman Framework This is a two-dimensional matrix that can be used to view and define an enterprise. It is a taxonomy for organizing architectural artefacts (e.g. documents and models) that takes into account both whom the artefact targets and what particular issue is being addressed.

The Zachman Framework This is a two-dimensional matrix that can be used to view and define an enterprise. It is a taxonomy for organizing architectural artefacts (e.g. documents and models) that takes into account both whom the artefact targets and what particular issue is being addressed.

5.5 IT SERVICE STRATEGY AND APPLICATION DEVELOPMENT

IT strategy and service strategy are both directly linked with application development in a number of different areas. The IT strategy combined with the underpinning service strategy lifecycle will serve as a primary feed into governance and application development. Decisions such as build vs. buy can also be influenced by IT strategy and the service strategy lifecycle. One of the main activities within the service strategy lifecycle is the classification of service assets. A well-defined service strategy combined with service asset classifications can empower business and IT leaders to make informed decisions without being intimately familiar with every aspect of a given service.

Application development teams should maintain alignment with service strategy by incorporating it into individual product line strategies and internal development efforts. While service strategy is created to drive the fulfilment of the desired business objectives, application development plans should be aligned to support service and IT strategy. In a sense, the application development strategy will have its own 4 Ps of strategy (perspective, position, plans and patterns) but it derives the overall direction from the service and IT strategy. This can also play a key role in helping the organization achieve the appropriate balance of innovation vs. operations.

Like other IT service providers, the application development providers should examine and validate their strategy (4 Ps of service strategy) within the context of the overarching IT strategy. If ‘time to market’ with new offerings is a primary objective or strategy, then the application development team can begin to align or position itself for that strategy from a people, process and technology perspective.

The service and IT strategy combined with the results from continual service improvement (CSI) can also play an important role in the design of upstream application development processes, the software development lifecycle and the associated service delivery tracks. For example, if the IT service strategy includes moving the organization to a certain mix of ‘commercial off the shelf’ (COTS) solutions, there may be incentives or mandates built into the decision support processes that begin to lean the organization that way.

5.6 CREATING A STRATEGY FOR IMPLEMENTING SERVICE MANAGEMENT PROCESSES

This publication has focused primarily on how a service provider defines a service strategy, and how it defines strategies for services themselves. However, the way in which services are managed is also a critical success factor for the service provider.

This section therefore focuses on how to define a strategy for implementing service management processes. It is very important that organizations should not simply try to ‘implement service management’ as an entire framework in a single project or programme. The objectives of the organization must be clearly defined and then the components of service management that will support those objectives carefully scoped and implemented.

In addition, it is important to note that this section is a guide, not a mandatory set of techniques and methods. Many organizations will have their own approaches to conducting activities like defining a mission and vision, and for identifying risk. If these are in place in the reader’s organization, section 5.6 might not be as relevant as it is to those readers who do not have formally established approaches for implementing this type of initiative.

ITIL will identify the major dependencies and linkages between processes, so that the organization can define how the processes they are implementing today will evolve and interface with processes that may be implemented in the future.

The implementation strategy for implementing service management processes will be defined and executed using the same lifecycle as the services, i.e. strategy, design, transition, operation and continual improvement. The tools and approaches defined in each stage will also be helpful in defining and executing an implementation strategy for service management processes, especially the seven-step improvement process of continual service improvement.

It must also be emphasized that simply implementing a set of processes and tools will not automatically be successful. There are a number of areas that need to be addressed, including:

![]() Clearly defining the business needs and objectives, which will determine the strategy. Without these, it will be difficult to sustain the implementation of the processes and tools through their lifecycle.

Clearly defining the business needs and objectives, which will determine the strategy. Without these, it will be difficult to sustain the implementation of the processes and tools through their lifecycle.

![]() Only those processes and tools that support these business needs and objectives should be implemented, rather than an indiscriminate implementation of processes, simply because they exist in ITIL.

Only those processes and tools that support these business needs and objectives should be implemented, rather than an indiscriminate implementation of processes, simply because they exist in ITIL.

![]() The implementation itself will be executed using formal project and programme management methodologies and tools. Thus the strategy will identify the projects that will be initiated and how they will be managed, and will also identify an overall project or programme manager (depending on the size and scope of implementation).

The implementation itself will be executed using formal project and programme management methodologies and tools. Thus the strategy will identify the projects that will be initiated and how they will be managed, and will also identify an overall project or programme manager (depending on the size and scope of implementation).

![]() A service management programme will change the culture and politics (and possibly the structure) of the organization. Management should be aware of this, and should be prepared to support, and sometimes enforce, these changes. Every implementation strategy should therefore include a clear strategy on how these changes will be managed.

A service management programme will change the culture and politics (and possibly the structure) of the organization. Management should be aware of this, and should be prepared to support, and sometimes enforce, these changes. Every implementation strategy should therefore include a clear strategy on how these changes will be managed.

![]() Simply implementing processes and assigning owners to these will not guarantee successful implementation or ongoing operation of the processes. A successful service management strategy will need a formal service management system – which identifies all the interrelationships between the processes, resources and tools, and which ensures that controls are properly defined and enforced.

Simply implementing processes and assigning owners to these will not guarantee successful implementation or ongoing operation of the processes. A successful service management strategy will need a formal service management system – which identifies all the interrelationships between the processes, resources and tools, and which ensures that controls are properly defined and enforced.

The difference between an organizational strategy and an implementation strategy

It is important to note that an implementation strategy for ITSM processes does not follow the same steps as the strategy management process in section 4.1. This is because it forms part of the execution of the corporate and IT strategies. In the larger organizational context this implementation strategy is a tactical project or programme plan, and not a strategy in and of itself – even if it is considered strategic by the IT organization staff.

5.6.1 Types of service management implementation

There are almost as many strategies for service management as there are organizations that have implemented it. However, they typically conform to one of four patterns, based on the current situation of the organization. This section is based on ideas from Strategic Selling (Miller et al., 1995).

5.6.1.1 Even keel mode

‘Even keel’ is a sailing term used to describe a sailing boat that is in calm weather and does not need any special techniques or tactics to move forward. Winds are favourable and sailing is straightforward.

Decision makers feel that their organizations are well managed and on track to meet their organizational objectives. Although there may be some minor difficulties within IT, these are not significant enough to initiate any projects aimed at changing the way IT is managed.

In many cases their position is correct. If IT is a component of the organization’s strategy and has drafted and executed plans that meet the organization’s requirements, it is unlikely that they will need to make any fundamental changes to their current practices. It is also very likely that they are using basic IT service management practices to a greater or lesser degree.

The appropriate service management strategy in these cases is to continue to focus on CSI and ensure that the organization continues to grow good service management practices over time.

The appropriate strategy for service management is the same as the performance projected by the organization’s leaders, in other words, IT should continue to do exactly what is in the existing plans.

In other cases, decision makers in IT may feel that everything is fine, whereas they are actually out of touch with the business, and are not part of the overall business strategy. Unfortunately, this is a very difficult situation in which to introduce IT service management. Decision makers often feel threatened by any attempts to change the current situation or challenge their perceptions – which is why they are in this situation in the first place.

In these cases the person wishing to introduce service management to resolve the situation has limited options, including:

![]() Being promoted into a leadership position and initiating a comprehensive assessment of the current situation, effectively moving the organization into trouble or growth mode.

Being promoted into a leadership position and initiating a comprehensive assessment of the current situation, effectively moving the organization into trouble or growth mode.

![]() Convincing the current leaders that an assessment is necessary. Experience shows that this option is not very effective, unless the person requesting the assessment is very influential. In most cases the assessment will result in further denial by the decision makers and make them more entrenched in the existing practices. This could also result in the person requesting the assessment losing their position.

Convincing the current leaders that an assessment is necessary. Experience shows that this option is not very effective, unless the person requesting the assessment is very influential. In most cases the assessment will result in further denial by the decision makers and make them more entrenched in the existing practices. This could also result in the person requesting the assessment losing their position.

![]() Maintaining silence, monitoring the situation and waiting for a significant failure to introduce IT service management. This could also have negative consequences – decision makers could blame the individual for having had the solution and withholding it. In addition, it may take a long time for an appropriate situation to arise, which is frustrating and demotivating for the individual.

Maintaining silence, monitoring the situation and waiting for a significant failure to introduce IT service management. This could also have negative consequences – decision makers could blame the individual for having had the solution and withholding it. In addition, it may take a long time for an appropriate situation to arise, which is frustrating and demotivating for the individual.

![]() Resigning and joining an organization more suited to their enthusiasm and skills, especially if they are passionate about IT service management.

Resigning and joining an organization more suited to their enthusiasm and skills, especially if they are passionate about IT service management.

5.6.1.2 Trouble mode

These organizations have recognized that there is a significant weakness or problem with the way in which IT is managed. This is usually seen in repeated outages, unreliable changes, customer dissatisfaction, capacity shortages, uncontrolled spending etc. Whatever the symptom, decision makers understand that they need to take significant action. Initially they might have invested in some short-term fix that has not been successful, and now recognize the need for a more comprehensive management approach.

This is a good situation to initiate a service management programme, since the decision makers recognize the need for it, and the business will often only find a rigorous, proven approach to be credible. In addition, there is usually a greater willingness to spend money to resolve the situation.

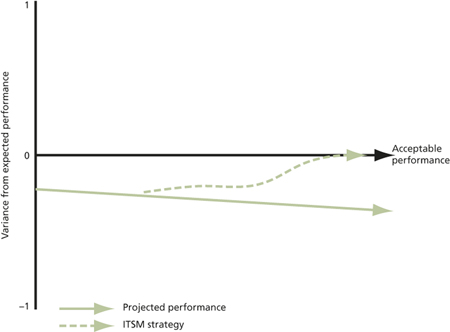

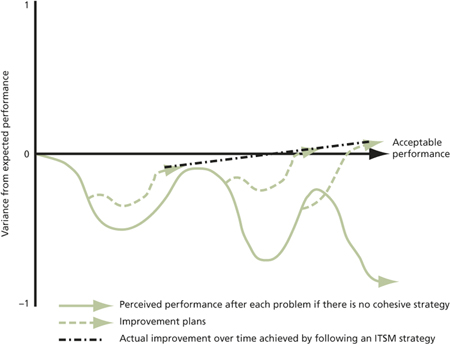

Figure 5.7 illustrates the appropriate strategy for organizations in trouble mode. This diagram shows the IT service management strategy will focus on building a solution that solves the immediate problem and moves the organization out of trouble. For example, if the problem is unreliable changes, the project will focus on building a centralized change management process, configuring and implementing the appropriate tools, and ensuring that all IT personnel are trained to use the new processes and tools.

In this type of situation, it is often not helpful to talk about ITIL or proprietary frameworks. The decision makers know that they are vulnerable, and that some vendors may attempt to exploit the situation by tying them into a large, complex solution that goes far beyond their immediate needs. All the decision makers want to see is that they have resolved the problem, and have restored stability and their credibility. The project team should therefore focus on the specific service management actions needed to resolve the problem, rather than try to ‘sell’ the decision makers on ITIL. Although the team should be open and mention that their approach is based on industry standards and best practices, they should emphasize the nature of the solution.

Figure 5.7 Strategy for organizations in trouble

However, there are dangers to the approach of using service management to move an organization out of trouble. Fixing the immediate problem may provide stability in the short term, but it might highlight (or even create) additional problems later. For example introducing change management solves one set of problems, but it is unlikely that poorly controlled changes are the only problem, since poor change management is only a symptom of a broader lack of control and service management. Continued performance problems or repeated incidents will result in even greater levels of dissatisfaction from users and customers who thought that these were a thing of the past.

Figure 5.8 Dealing with repeated trouble

The result is a pattern of repeated trouble. Figure 5.8 illustrates this pattern. Over time, IT reacts to a series of problems, using service management to fix each one. The overall impression of the organization (represented by the solid coloured line – perceived performance) is that IT service management does not address all their requirements and in fact has been making the organization progressively worse. In addition, IT loses credibility at an increasing rate.

Of course, this is not true, since failure to take any action in the first place would have resulted in even more catastrophic outcomes – but perception is very powerful, and invariably IT service management, ITIL and the project team will get the blame for the situation.

To prevent this situation Figure 5.8 illustrates a series of actions aimed at dealing with each progressive problem, while over time increasing the level of control and service quality. The key to success is to define an overall ITSM strategy that uses ITIL techniques to identify each subsequent trouble area before it develops and implement the solution before the problem manifests itself. The strategy follows an incremental implementation cycle, where each initiative builds on the previous, and each initiative results in continual growth of the IT organization’s performance.

After the first few problem situations are resolved (usually no more than three), the organization will revert to either even keel (see section 5.6.1.1) or growth mode.

Where to start when dealing with trouble

The starting point will be different in every organization, depending on the initial problem being experienced. Most organizations tend to start with incident and problem management, since the ability to deal with outages tends to be one of the first challenges that presents itself – no matter what is wrong behind the scenes.

The next most common starting point is change management, since problems are often a reflection of siloed groups being unable to coordinate their activities effectively. This is most visible when changes are deployed.

The most important guideline is to start in the area that is causing the most pain to the organization. While working on a solution to that problem, the team should already be assessing the situation to identify the next problem that will emerge. For example, starting with incident management will almost always result in detailed work on improving communication between the technical management, application management and operations management functions. This will almost always result in defining better change management processes, which will almost always result in the need for a more cohesive approach to configuration management.

Projects in this type of organization tend to be more ‘bottom up’ and tend to focus first on the areas contained in ITIL Service Operation and ITIL Service Transition.

Importantly, no matter which area is implemented first, they will all require a basic understanding of what services are delivered by IT. This means that most projects include the definition of a basic service catalogue as an integral component.

5.6.1.3 Growth mode

Organizations in growth mode have made a strategic decision to improve or change the organization significantly over the planning period. For example, they might be expanding into new markets, establishing new lines of business or improving the performance of the organization as a whole.

The organization’s strategy recognizes that IT is part of the solution to achieving this level of growth. Decision makers will look for a comprehensive, strategic approach, such as IT service management, to achieve this growth.

In these situations it is appropriate to talk about IT service management as a framework and to articulate each of the components and how they will enable the overall strategy. The implementation strategy for service management processes will be to implement the whole of the framework over time.

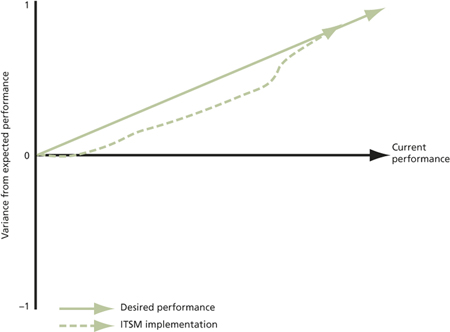

Figure 5.9 illustrates an organization in growth mode. The organization’s strategy requires a significant improvement in IT’s performance (the coloured line). The IT service management project team needs to define an approach in which all service management processes and functions are deployed to the appropriate levels over time. Figure 5.9 shows that there is a time lapse between the definition of the organization’s strategy and the IT service management implementation. This is because it will take a significant amount of time to conduct the ITSM assessment, set the strategy, prepare resources etc.

Unlike trouble mode, it is important to stress the fact that IT’s strategy is based on a comprehensive framework, based on best practices like ITIL or standards such as ISO/IEC 20000. This will reassure the organization’s executives that IT’s plan is more likely to address the overall organizational strategy and that IT has a good chance of succeeding. In other words, emphasizing the framework reduces the organization’s perception of IT risk.

Figure 5.9 Strategy for organizations in growth mode

Where to start to achieve growth

Growth-based projects generally tend to start with a comprehensive assessment of all aspects of their organization, ranging from existing processes, tools and technology, to the culture and structure of the organization. This is then compared to the growth strategy and the most significant gaps or adjustments are addressed first. There is no correct approach to this, but the early stages of the project will include cataloguing every aspect of the organization and marking those that will need to change, and how they will need to change.

These projects generally have a ‘top-down’ approach that focuses on structural and architectural changes first. Any ITSM processes or functions that are necessary to achieve this are implemented first. This implies that the processes in ITIL Service Strategy and ITIL Service Design tend to be the first processes that will be changed or implemented.

5.6.1.4 Radical change mode

These are organizations that are going through a fundamental change as an organization – for example, they might be outsourcing IT or going through a merger or acquisition.

These projects are similar to those for organizations in growth mode, with two major differences:

![]() The first phases of the project (assessment, planning, designing and implementing the solution) all need to happen very quickly. This is followed by a long and intensive programme of entrenching the new practices into the new organization.

The first phases of the project (assessment, planning, designing and implementing the solution) all need to happen very quickly. This is followed by a long and intensive programme of entrenching the new practices into the new organization.

![]() The project is managed by a small group of people who may not disclose the details of the project until an appropriate time, usually around the implementation phase. This demands a less participative implementation style and makes it difficult to ensure that the requirements are comprehensive and accurate at operational levels.

The project is managed by a small group of people who may not disclose the details of the project until an appropriate time, usually around the implementation phase. This demands a less participative implementation style and makes it difficult to ensure that the requirements are comprehensive and accurate at operational levels.

These two differences usually mean that the project is structured as an overall programme with a comprehensive strategy, and several projects – each aimed at building a different aspect of the new organization. It also requires that the project is driven more directly by senior managers since the plans need to be changed when unforeseen situations arise – and this is very likely to happen. For a short time during the transition, the overall programme becomes the governance of the changing organization.

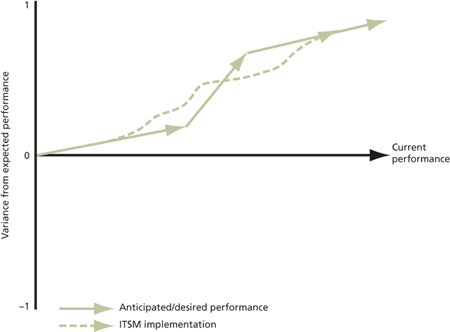

Figure 5.10 illustrates the type of strategy required for organizations in radical change mode. The actual change is preceded by a significant amount of preparation activity. This often goes beyond planning and includes the actual implementation of key processes (such as service portfolio management and business relationship management) and functions (such as a new financial management function for restructured organization and services). The project will also focus on preparing for new standard operating procedures for vital business functions, and new documentation and reporting standards.

When the actual change occurs, there is a period when the rest of the organization is educated about the new processes and functions and how they will work in future. At that time, the project team will no longer be restricted by confidentiality requirements, and will begin working on the more detailed operational processes, such as change, incident and problem management.

Figure 5.10 Strategy for organizations planning radical change

5.6.2 Defining a vision and mission for the service management implementation

Once the planning team understands the overall strategy of the organization, and what business or IT management issues they need to address, they should define a vision and mission. This is the ‘perspective’ in the 4 Ps of service strategy.

A clear vision enables the implementation project team and all of its stakeholders to understand the strategic value initiative and thus achieve greater support. A good vision statement has four main purposes:

![]() To clarify the direction of an initiative

To clarify the direction of an initiative

![]() To motivate people to take action that moves the organization to make the vision reality

To motivate people to take action that moves the organization to make the vision reality

![]() To coordinate the actions of different people or groups

To coordinate the actions of different people or groups

![]() To represent the view of senior management as they direct the organization towards its overall objectives.

To represent the view of senior management as they direct the organization towards its overall objectives.

5.6.2.1 Defining the vision and mission

The planning team should be very careful to take the organizational vision and strategy into account as they develop the vision and mission for the service management process implementation. This section deals with the vision and mission for the service management process implementation, not for the entire organization. It may well be that the vision of the organization will change if the project is successful, but that is something that needs to be handled by the organizational executives as part of a separate exercise.

One of the most common ways of developing a vision and mission is to conduct a workshop with key stakeholders. The outcome of the workshop is to have a vision statement that each individual is prepared to support and that they can explain convincingly.

This seems to be fairly simple, but in reality this is probably one of the most difficult things to achieve. Every person in the workshop has their own opinion about what is wrong and how to solve the problem. In the beginning stages of the workshop it is not uncommon to find that every person there believes that the other people are the ones with a problem, and he or she has just been asked to attend to give the rest of the group the benefit of their experience!

In addition, each person has their own set of objectives and aspirations, which are sometimes in conflict with those of other people in the meeting.

It is common for the group to argue about single words in the statement that, to an outsider, seem to be insignificant. This is not because the word is wrong, but is an attempt by the participant to negotiate the terms whereby they will accept the vision statement.

A good facilitator will be sensitive to the need of each of the people involved, but will also drive them towards a negotiated settlement. In a sense the actual statement that is documented is less important than the fact that everyone in the room is prepared to work together on achieving the same objective.

It is therefore not always crucial to achieve consensus – just moving someone from being opposed to where they are prepared to live with the outcome is a win.

The nature of individual agendas and the negotiation that occurs in these workshops introduces a whole range of group dynamics, which a facilitator should ideally be able to see face to face. These dynamics could include:

![]() An individual verbally stating that they agree with the vision, but their body language indicating otherwise. If they leave the meeting without this being resolved they will work to undermine the project

An individual verbally stating that they agree with the vision, but their body language indicating otherwise. If they leave the meeting without this being resolved they will work to undermine the project

![]() An individual being a little emotional about the direction the meeting is taking because it threatens their sense of security or conflicts with their personal aspirations

An individual being a little emotional about the direction the meeting is taking because it threatens their sense of security or conflicts with their personal aspirations

![]() The group feeling bullied by a person with strong views or a power base that is not immediately obvious

The group feeling bullied by a person with strong views or a power base that is not immediately obvious

![]() Some individuals in the group needing to be drawn out before they contribute

Some individuals in the group needing to be drawn out before they contribute

![]() A lack of focus in some individuals distracting the group.

A lack of focus in some individuals distracting the group.

The very nature of the workshop makes it difficult to run virtually, unless the participants know each other well. Most workshops take two to three days, and it is recommended that all participants meet in the same physical location. It is also advisable to run the workshop off-site to ensure minimal disruption to the participants.

Step 1 – Where have we come from?

Vision and mission statements do not occur in isolation. There has to be a reason for the team getting together to discuss the need for IT service management. The first phase of defining a vision and mission is to understand the events and dynamics that have led us to this point.

This part of the workshop documents the factors that have led to this meeting. These could include:

![]() Significant events

Significant events

![]() Key people, actions and decisions

Key people, actions and decisions

![]() Environmental factors

Environmental factors

![]() Locations (e.g. is this relevant to a specific site or does it relate to multiple sites?)

Locations (e.g. is this relevant to a specific site or does it relate to multiple sites?)

![]() Previous objectives and projects and their success or failure.

Previous objectives and projects and their success or failure.

Note: Some of these factors may have been negative. The facilitator should ensure that these are documented, but that the meeting is not side-tracked into a detailed discussion about the effects, personalities or assigning of blame.

Step 2 – Assessing the context

In this section of the workshop the team will attempt to capture all relevant environmental factors that could influence what the vision and mission will be. Ideally, the assessment should have been conducted and will have identified most of these areas; however, it is still necessary for the team to consider these areas when defining the vision and mission.

Whereas the previous section focused on what happened in the past, this section focuses on what could affect the future. These factors could include:

![]() External environment:

External environment:

![]() Technology

Technology

![]() Economic

Economic

![]() Political

Political

![]() Legislation

Legislation

![]() Internal environment:

Internal environment:

![]() Business plans and objectives

Business plans and objectives

![]() Political

Political

![]() Financial

Financial

![]() Requirements expressed by any stakeholders or potential stakeholders.

Requirements expressed by any stakeholders or potential stakeholders.

This part of the workshop is best done using brainstorming techniques where participants are able to contribute items freely. What may seem to be irrelevant at first may turn out to be significant at one of the later stages of the workshop.

Step 3 – Situational analysis

This part of the workshop is an extension of the previous one, except that here the team will review what other organizations have done in the area being considered. Potential inputs to this discussion are:

![]() Projects undertaken by a competitor

Projects undertaken by a competitor

![]() Case studies (the itSMF conferences have a wealth of case study presentations)

Case studies (the itSMF conferences have a wealth of case study presentations)

![]() White papers

White papers

![]() Industry research (e.g. benchmark reports).

Industry research (e.g. benchmark reports).

This part of the workshop will document any relevant factors about what these organizations have done including:

![]() Any environmental factors that influenced the organization

Any environmental factors that influenced the organization

![]() Which vendor organizations were involved

Which vendor organizations were involved

![]() What tools or technologies were used

What tools or technologies were used

![]() What alternatives were considered and why they were rejected

What alternatives were considered and why they were rejected

![]() What mistakes were made

What mistakes were made

![]() Key outcomes.

Key outcomes.

In this part of the workshop the facilitator should ensure that relevant factors are documented, but should prevent the workshop from becoming a detailed discussion about competitive technologies, vendors or companies. The aim is to understand what influenced the other organization’s vision, not to debate the merits of various approaches.

At this stage, the team should take into account any SWOT analysis outputs. If this was not done during the assessment, it should be done here. To recap, a SWOT analysis analyses the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats currently facing the team. It is also a helpful tool for the facilitator to summarize Steps 2 and 3 on one page.

Key things to remember in SWOT analysis are:

![]() Strengths can be built upon

Strengths can be built upon

![]() Weaknesses need to be dealt with or turned into strengths

Weaknesses need to be dealt with or turned into strengths

![]() Opportunities should be exploited

Opportunities should be exploited

![]() Threats need to be minimized.

Threats need to be minimized.

These items will assist in articulating the vision and mission and ensuring that they are more realistic.

Step 4 – Define the possibilities

Now that the analysis has been completed the workshop becomes creative. In this step, the team is asked to imagine a future state in which the issues in the previous three steps have all been dealt with.

This part of the workshop is likely to result in all kinds of ideas and suggestions, often uncoordinated and in no particular order. It is important to note that that this is not the step where the vision and mission are defined. This is where the team has free rein to imagine what could be possible. This provides the raw materials from which the vision and mission will eventually be built.

It is important not be too restrictive, but at the same time to maintain some sort of structure to the responses so that they do not get lost or minimized. A number of techniques can be helpful here, but one that combines many of those techniques is the newspaper technique.

Here participants work as individuals or small groups and create a newspaper front page to describe the outcome of the project. Each front page should contain:

![]() One or more articles

One or more articles

![]() At least one headline

At least one headline

![]() At least one article describing the successful outcome of the project

At least one article describing the successful outcome of the project

![]() A picture illustrating the article (this is important to capture symbolism that may not be easy to express in words)

A picture illustrating the article (this is important to capture symbolism that may not be easy to express in words)

![]() Some of the more creative groups will also create adverts and ‘related stories’ to fill up their front page.

Some of the more creative groups will also create adverts and ‘related stories’ to fill up their front page.

Note: This stage also provides input to the awareness campaign.

Step 5 – Restating values, policies and guiding principles

After Step 4 the team will be fairly excited about the vision that is emerging. One of two things can happen at this point:

![]() The team could get carried away by their enthusiasm and start creating a vision that is not feasible or practical.

The team could get carried away by their enthusiasm and start creating a vision that is not feasible or practical.

![]() Some members of the team, realizing this, may start to negate the visions of other members, resulting in a kind of team despondency – and a vision that is not ambitious enough.

Some members of the team, realizing this, may start to negate the visions of other members, resulting in a kind of team despondency – and a vision that is not ambitious enough.

A skilled facilitator deals with this by revisiting the objective of the meeting and getting the team to restate any values or guiding principles of the organization that may be relevant to this project. Please note that this may relate to the organization as a whole, or just to a single department or group within the organization.

The values, policies and guiding principles provide input to creating the vision, but they are also the basis for the mission statement, which will also need to be articulated at this stage.

This part of the workshop should not take too long and the facilitator should be careful not to labour the point too much. All they really need to determine is whether their thinking is consistent with the purpose and culture of the organization.

Step 6 – Stating the vision and mission (getting agreement)

The facilitator will now work with the group to define the vision and mission statements. This is normally done in two steps:

![]() Summarize the vision and mission themes. The individuals or small groups in Step 4 will have created a number of different views of the vision and mission. However, there will be common themes running through each of these. These themes should be summarized by the facilitator, although the wording should be agreed by the team.

Summarize the vision and mission themes. The individuals or small groups in Step 4 will have created a number of different views of the vision and mission. However, there will be common themes running through each of these. These themes should be summarized by the facilitator, although the wording should be agreed by the team.

![]() Merge the themes into vision and mission statements. Again, this will be done by the facilitator with the team agreeing to the final wording.

Merge the themes into vision and mission statements. Again, this will be done by the facilitator with the team agreeing to the final wording.

Having the facilitator summarize the themes into vision and mission statements externalizes them from the team and ensures that they think of it as a team effort. This is important in ensuring that each of the team members feels equally responsible for the vision and willing to take ownership of it.

It is important that the group then obtains buy-in from senior management to demonstrate their commitment to the vision and mission. If they do not achieve this senior management buy-in then the risk of project failure will be increased.

Vision killers

The National Association of School Boards (NASB), on its website, encourages facilitators to watch out for the following factors which could derail the visioning process:

![]() Tradition

Tradition

![]() Fear of ridicule

Fear of ridicule

![]() Stereotypes of people, conditions, roles and governing councils

Stereotypes of people, conditions, roles and governing councils

![]() Complacency of some stakeholders

Complacency of some stakeholders

![]() Fatigued leaders

Fatigued leaders

![]() Short-term thinking

Short-term thinking

![]() ‘Naysayers’ (people who disagree with all ideas from the team, even when they have none of their own).

‘Naysayers’ (people who disagree with all ideas from the team, even when they have none of their own).

Confirming the direction

Although the visioning workshop should have taken into account the business objectives and strategy, it is always possible that the team created elements of the vision that may be in conflict with the strategy and direction of the rest of the organization.

If the senior managers who determined the strategy of the organization do not support the changes required to meet the ITSM vision, then it will not succeed.

The team should confirm that the vision and mission are in line with the organization’s strategies by discussing it with the appropriate level of management, as well as by consulting any documents related to the organization’s strategy.

5.6.3 Service management assessment

Once the organization knows what type of strategy it needs to follow, it is necessary to do an assessment to confirm the strategic approach and define a more detailed service management implementation strategy. An assessment will confirm the current situation, identify strengths and weaknesses and propose an approach for service management implementation. Many organizations prefer to define the mission and vision for service management (as part of the service strategy) before conducting the assessment.

Please note that, while the assessment will mirror the strategic assessment performed in strategy management, it is a different assessment. The strategic assessment focuses on the overall strategy of the organization, and how that relates to services. The service management assessment is a tactical assessment focused specifically on what elements of service management are required to meet a specific set of business issues and IT management challenges. A service management assessment forms part of the execution of the overall service strategy.

Although the subject of assessments is covered in ITIL Continual Service Improvement, this section contains a brief overview of assessments for the sake of completeness.

The assessment will identify areas of strengths (that can be built upon) and weaknesses (that need to be addressed) specifically related to the challenges that the organization is attempting to solve. The output of the assessment will be a report which will be submitted to the team defining the strategy. They will use it as an input to defining the strategy, and will use extracts or summaries to raise stakeholder awareness. Trying to define a strategy without an assessment would be like trying to run a race without knowing where the starting line is.

Another reason for conducting the assessment is to establish a baseline for the measurement of improvements. When implementing a service management process, there may be a temporary loss incurred during the implementation of a new process or change to a process. Once overcome, this temporary loss should be replaced with measurable improvement.

A good assessment will enable the team defining the implementation strategy for service management processes to understand the variables that can make or break the success of the project. These variables form the basis for the rest of this section and can be summarized as follows:

![]() External reference An ITSM project or programme will usually refer to an external reference as a guideline – in the same way as a driver would refer to a map to ensure that they are on the correct road. Most assessments are tied to a specific standard, framework, reference model or methodology. Understanding that no assessment is objective is an important step in a successful ITSM implementation. Even ITIL-based assessments tend to vary in how best practice is interpreted.

External reference An ITSM project or programme will usually refer to an external reference as a guideline – in the same way as a driver would refer to a map to ensure that they are on the correct road. Most assessments are tied to a specific standard, framework, reference model or methodology. Understanding that no assessment is objective is an important step in a successful ITSM implementation. Even ITIL-based assessments tend to vary in how best practice is interpreted.