CHAPTER 1: ISO 9001 REQUIREMENTS, MYTHS, AND GUIDANCE

In this chapter, we look in-depth at the requirements of ISO 9001:2015, including some of the more common myths associated with each requirement and guidance based on more than 6 years of implementation in more than 50 organizations. A copy of the ISO 9000, and ISO/TS 9002 standards should be obtained to gain the best understanding of ISO 9001.

At the time of writing, ISO 9004 is being considered for updating as a requirements document to complement ISO 9001, so comments regarding that guidance are not included. Readers may wish to visit the ISO website for the latest details. More on these guidance documents later.

Some of the myths may have originated around the earlier versions and are commonly applied to the 2015 version of ISO 9001, so have been included here for those readers coming to ISO implementation for the first time.

ISO 9001 has five key sections:

1. Introduction

2. Scope

3. Normative References

4. Terms and Definitions

5. Quality Management Systems – Requirements

Rarely are all the texts of this 27-page document ever fully read and completely understood. Instead, most readers tend to focus on the section 4 requirements, mainly because that is where the requirements for a QMS are specified. It is these requirements, plus the desire by an organization to be certified, which draw attention away from key information found in sections 1 through 3! Sadly, this is a little like children being taught to recite multiplication tables without knowing the mathematical purpose.

History has shown us that, typically, quality management activities in an organization were frequently performed to meet customer requirements – often through compliance with a contractual obligation. Customers flow down their supplier quality assurance requirements or require a supplier to be ISO 9001:2015 certified as a basis of doing business with them. No doubt many readers will be seeking information on ISO 9001 for that very purpose. This is still true today, however, if we adopt the popular maxim of Dr. Deming: “Quality is everyone’s responsibility.” Clearly the quality system should be embedded in the organization’s everyday operations and functions, and not seen as an ‘appendage’ to the core of that organization.

It was only with ISO 9001:2000 that any thought was really given to providing, in the document itself, a description of how all the requirements of the Standard were supposed to come together – as the basis of the organization’s QMS.

This situation, where users simply refer to only the section 4 requirements, exists despite volumes of guidance being published by the ISO technical committees and a significant number of books on implementing and auditing ISO 9001! Not spending time to grasp the whole document may delay the fullest understanding of its application. Following a major online survey of users in 2014, the technical committees responsible for the creation of the ISO 9000 standards have attempted to make the requirements align better with the needs of an organization to help make the QMS integral to the organization’s business processes.

Now entering the sixth year of publication and with another user survey being closed in December 2020, it has been decided that there will be no revisions to the 2015 requirements – this should see users through to 2025 without any changes being necessary to their QMSs.

Top tip

Obtain copies of ISO 9000, ISO 9001, and ISO/TS 9002 to study. Along with the guidance here, you’ll be off to a good start.

Introduction

The introduction to ISO 9001 talks about the adoption of a QMS as being a strategic decision and to help improve overall performance and as a basis for sustainable development initiatives. It lists the potential benefits of implementing a QMS based on the requirements of the Standard:

• Consistently supplying products and services that meet applicable requirements (customer, regulatory, etc.)

• Opportunities to enhance customer satisfaction

• Addressing risks and opportunities associated with the organization’s context and objectives

• Demonstrating conformity (this would include third-party certification)

• It further states that the Standard doesn’t imply any type of formal approach to risk management

It is interesting to note that the word ‘risk’ is introduced – but then mentioned only a few times in the requirements sections 4 through 10. Perhaps controversially, many quality professionals will offer opinions that the concept of risk was always embedded in the application of ISO 9001 – now it is clearly stated.

Quality management principles are described in section 0.2 of the Introduction, including:

• Customer focus

• Leadership

• Engagement of people

• Process approach

• Improvement

• Evidence-based decision making

• Relationship management

Despite being mentioned in the Introduction and throughout the various requirements sections, the description refers the reader to ISO 9000 2.3 for further explanations of each.

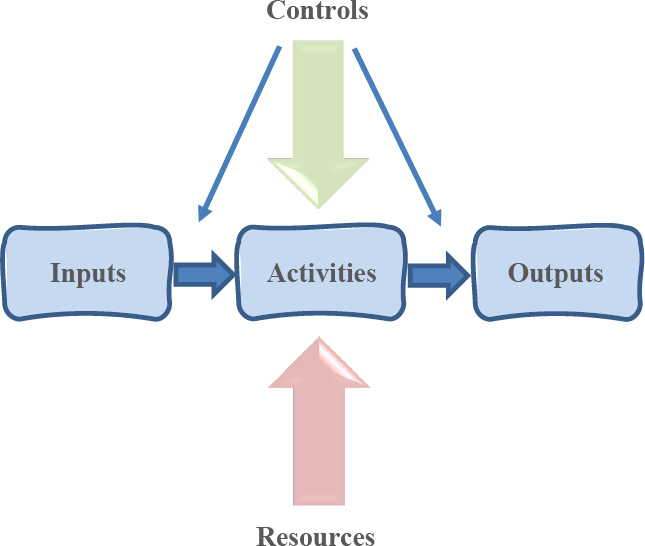

The “Process Approach” is section 0.3 of the Introduction, which describes several concepts that are supposed to be incorporated in the organization’s approach to quality management – a system of interlinked and interacting processes. A diagram, on page viii of ISO 9001 (figure 1), shows elements of a single process in terms of:

• Sources of inputs (predecessor processes)

• Inputs (energy, matter, information)

• Outputs (energy, matter, information)

• Receivers of inputs (subsequent processes)

Also shown are possible control points for measurement and monitoring (specifically at input and output).

Figure 1: Elements of a process

It is worth remembering that some key features which should have caused the conventional wisdoms of previous versions of ISO 9001 to be laid to rest have, instead, created more mythology.

These include the following:

• There is no required quality manual. Only the scope of the QMS, quality objectives, and quality policy are required to be documented.

• There is no requirement for a formal approach to risk management – it even states this in Annex A.4 “Risk-based thinking”.

• There is no requirement to have objectives for all the QMS processes.

• There is no requirement for any of the processes of the QMS to be documented.

• There is no requirement for internal audits to be process-based.

• There is no requirement to have a process for preventive action.

It would be easy for users to fall into the trap of believing these because the Standard doesn’t mandate any types of manuals, procedures, or other types of documentation; the organization could simply write the documents that are specifically mandated by ISO 9001 and leave it at that. Nothing could be further from the truth, however, if we consider the requirements stated in section 4, “Context of the Organization”; in meeting the “needs and expectations of interested parties,” it is likely that the organization would identify a need to document certain things for:

• Training purposes

• Knowledge retention

• Governance or similar policy

• Meeting customers’ expectations/requirements, or regulatory agencies’ requirements

Indeed, it is difficult to conceive that improvements may be made to any process or related aspect without formally defining and documenting those things, so that improvements can be a) identified and b) implemented.

It is, as most readily understand, difficult to hit a moving target, and writing things down is a universally accepted place to start the improvement journey.

Another consideration of interested parties, especially customers and (if applicable) regulatory agencies, is that they may require the organization to document many of the plans, processes, responsibilities, authorities, controls, and actions necessary to assure the products had a good chance of being correct to the specification.

Top tips

Consider all the reasons the organization would create documentation of its QMS process, responsibilities, results, etc., and let that determine why and what forms the documentation. Engage all functions in the decision and the creation of documentation. People ‘own’ what they create.

Don’t be overly concerned about what hierarchy of documentation is needed. Find a placeholder in relation to the processes: input, control, resource, or output.

Don’t structure your organization’s QMS around the requirements of ISO 9001.

QMSs: Requirements

Scope (1)

Before anyone leaps into implementing a QMS based upon the ISO 9001 requirements, it’s highly recommended to read through the Scope at the very beginning – something which is often overlooked. The Scope section defines the conditions when an organization considers implementing a QMS, when it:

• Needs to demonstrate its ability to consistently provide products and services that meet customer and applicable regulatory requirements

• Aims to enhance customer satisfaction through the effective application of the system, including processes for improvement of the system and the assurance of conformity to customer and applicable statutory and regulatory requirements

It goes on to state that the requirements are generic and are intended to be applicable to any organization, regardless of its type or size, or the products and services it provides.

Myth Alert!

“My organization is too small to implement ISO 9001.”

Myth Busted!

As can be seen from the scope, ISO 9001:2015 is intended to be implemented by all types of organizations, no matter how big or small. It can be a challenge for many “micro-organizations”, (perhaps one, two, three or four people) to ensure some of the requirements of ISO 9001 are adequately implemented over time, especially aspects such as internal audits.

Top tip

Consider using an experienced, qualified professional on a part-time basis, to take care of some of the implementation aspects of ISO 9001. Tasks can include managing and reporting on the supplier relationships, internal audits, management reviews, liaison with external bodies such as calibration labs, certification bodies and their auditors and managing corrective actions and improvement opportunities.

Normative References (2)

Since the ISO 9001 standard is written to have the same meaning in many languages, it is important that words which represent key concepts on which a QMS are built have common definitions. Without a clear understanding of these key words, designing, implementing, and improving a QMS are not going to be as effective.

Discussions on Internet forums will quickly reveal how important it is to have a common understanding of terminology. One example, which we will explore in a later section, is defining competence. Online dictionaries show several definitions that may not fully address the intent, in the context of ISO 9001. This key definition isn’t found in the Standard itself, however, but in ISO 9000, which is the “Normative Reference.” It contains the terms and definitions necessary to guide the reader through the ISO 9001 requirements.

Competence, which is the subject of section 7.2 of ISO 9001, is defined in the vocabulary document – ISO 9000 (3.10.4) – as the “ability to apply knowledge and skills to achieve intended results.”

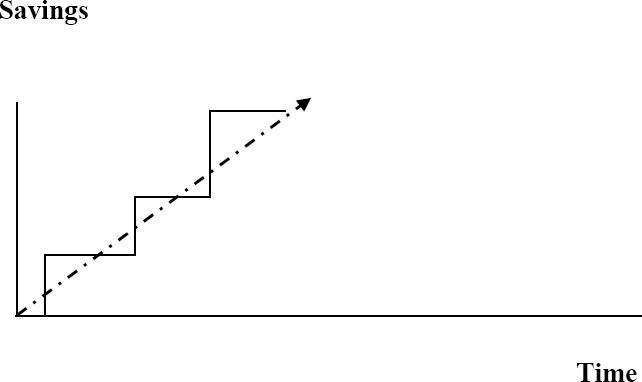

In considering the requirements specified, it is easier to see that once competencies have been defined (and demonstrated), some actions may be necessary, including training, to address any shortfalls identified. Such a process will, now a better understanding has been gained, lead to time and money being saved, compared to conventional training programs in which a number of hours of training are required, regardless of any need being identified for an individual employee.

Top tips

Ensure that everyone involved in the creation of the QMS fully understands the terminology applicable to their process.

For example:

• Training isn’t competency

• Calibration and verification aren’t the same thing

• Inspection and audit are not synonymous

• Nonconformities don’t require root-cause corrective action

• Calibration isn’t a simple check of a gauge against another

Terms and Definitions (3)

ISO 9001 has employed the terminology of “product” as the resulting output from the QMS. The background to the development of ISO 9001 was, after all, the military hardware-oriented Defence Standards. From user feedback since 1987, it became obvious that organizations which provided services (often alongside their product) had struggled to implement the requirements of ISO 9001, although having a formal QMS was found to be useful and often a customer requirement. The need for less product-oriented terminology was called for.

Under this heading, a clear statement is made that where “product” is mentioned, users may substitute “service” if this is applicable to their needs. Also, a reference is made here to the use of ISO 9000 – the vocabulary document – for other definitions and how the terms used are linked. This is particularly useful to demystify some relationships, for example the roles of controlling non-conformance and the need for corrective actions, which are frequently lumped together with (financially) disastrous results! Oddly, many organizations balk at spending the US$250 or so, when that cost can easily be avoided by using the direction the vocabulary provides. Compare that to the cost of responding to a certification body audit report that identifies major nonconformities!

The Context of the Organization (4)

The inclusion of this requirement was intended by the technical committee to provide an ‘anchor’ or connection from the issues of running an organization to the development and implementation of a QMS. Historically, quality and management systems have been perceived as something that is additional or extra to the actual business of managing an organization. Indeed, the word ‘quality’ often means the responsibility for its management is offloaded onto a designated individual, usually a quality manager. Part of the Annex SL or high-level structure adopted across many of the management systems-related ISO standards (ISO 14001, ISO 27001, et al), the Clause 4 requirements are intended to direct the organization to look to the future – a sort of strategic planning, without calling it that.

For the first time in traditional QMS requirements, there has been an attempt to align the organization’s quality system with its business operations in a manner that makes the resulting goals, processes, controls, measurements, and actions assist the overall success!

Sub-clause 4.1, “Understanding the organization and its context,” includes the need to “determine the external and internal issues that are relevant to its purpose and its strategic direction and that affect its ability to achieve the intended results of its Quality Management System.”

Reference is also made to the need to “monitor and review information” related to these issues.

Myth alert!

“These internal and external issues need to be addressed in a procedure.”

Internal and external issues can be simply addressed by an organization through the use of business analysis tools, such as SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats) or PEST (Political, Economic, Social, and Technological). These are macro views of the organization and give an indication of issues affecting an organization. Using SWOT will help identify internal (strengths and weaknesses) and external (opportunities and threats) issues.

For example, at the time of writing, in the western industrial marketplace, a SWOT would confirm that a key strength of many organizations is their people, in the following terms:

• Experienced

• Tenured

• Knowledgeable

• Skilled

• Flexible

• Etc.

However, as with many strengths, they can also be viewed as a weakness. In this case, many of these experienced and skilled employees are facing retirement. This ‘silver tsunami’ will result in the potential loss of a significant amount of organizational knowledge. Due to a variety of factors, education systems and employers have not prepared people to enter the workplace with even basic skills that are transferable to the workplace. The ‘risk’ becomes how the organization will address this weakness since it will, inevitably, adversely affect the ability to deliver a quality product.

The question becomes, within the scope of the QMS, what to do about this risk?

The ISO 9001 requirement doesn’t make it clear what is supposed to be done with this information. However, when considering the input to management review, it is clear that this information is the source of what would be reviewed and the results of addressing the weaknesses and threats, for example. More on this later, in section 6, “Planning”.

Once the SWOT is performed, it makes sense to keep a watchful eye on its content because changes, over time, will affect the analysis.

The Standard goes on, in sub-clause 4.2, to require the organization to “Understand the needs and expectations of interested parties.” Referencing ISO 9000, we can see that interested parties simply means stakeholders, i.e. the organization’s owners, customers, employees, and suppliers, and, as applicable, regulatory agencies. It is a requirement for the organization to determine:

• “The interested parties that are relevant to the Quality Management System and

• The requirements of these interested parties that are relevant to the Quality Management System.”

Once again, the need to monitor and review information about this is required.

One drawback of ISO 9001:2015 that can affect users is grasping how the requirements are intended to interrelate to form a true system. As we read through the sections, there are backwards references to previously stated requirements as a nod to their connectedness. Unfortunately, there are few (one?) forward-looking references and experience shows that the context of the organization requirements can be related to a key feature of an effective QMS – the “Management Review” requirement (9.3). As we will discuss later, there is no guidance within the Standard that points out this interrelationship to help readers understand how this system should function. Instead, they would have to purchase yet another ISO publication, in this case ISO/TS 9002 (which is a technical specification providing implementation guidance for ISO 9001), to obtain any information on such connectedness between clauses.

Top tips

A simple SWOT analysis is a good way to determine the internal and external issues. The organization’s leadership should conduct this analysis and use the ‘vital few’ issues to create a strategic plan of action.

Unless it’s not very obvious to the organization’s leadership, there is no need to rank the risks, even in a simple manner such as ‘high,’ ‘medium,’ or ‘low.’

The last part of the clause on the context of the organization deals with determining the scope of the QMS (4.3). As the word ‘scope’ suggests, an organization has some degree of flexibility to select what functions and activities, products and services fall within the ‘focus’ or the boundaries of the QMS – with some exceptions: If conformity to the ISO 9001 requirements is going to be claimed – let’s say for the purpose of being certified by a third-party conformity assessment body (a registrar) – then the requirements cannot be claimed to be not applicable if they affect the organization’s ability or responsibility to ensure conformity of products and services and customer satisfaction. In simple terms, if the organization creates new product design work, it cannot avoid compliance of the QMS with the 8.3 requirements – for any reason.

For example, if Apple were seeking ISO 9001 certification, it would not be able to claim that product design was inapplicable. Similarly, it cannot claim to manufacture, since – at the time of writing – manufacturing Apple products such as the iPhone, iPad and Apple Watch are carried out by contractors such as Foxconn Technology (the trading name of Taiwanese business Hon Hai Precision Industry Co., Ltd.). This may seem obvious at first sight, but the application of scope to a QMS is fraught with nuance and many rules.

In considering what is in and out of the scope of the QMS, the organization needs to consider the requirements above, relating to 4.1 Understanding the context and 4.2 Understanding the needs and expectations of interested parties.

The scope is required to be maintained as “documented information” – the first time this somewhat obtuse reference to any form of documentation is made. This terminology is referenced and discussed later. Typically, a scope statement might describe the products and services the organization offers to the marketplace, locations, and justification why some ISO 9001 requirements are not applicable – not performing product design is a classic example.

Examples include:

• “The design and manufacture of…”

• “The manufacture, maintenance, and servicing of…”

• “The distribution of…”

• “The management of technical engineering staff to…”

• “The installation, commissioning, service, and repair of…”

The product(s)/services are usually described, including other descriptions of specific industries served, materials used in the product, process types employed, etc., to give details to prospective buyers of the capabilities of the organization.

Turning to the final sub-clause of the first major requirement of ISO 9001, we see it relates to the QMS (4.4) and the processes that are included within it.

Myth alert!

“We’ll use the diagram in the ISO standard as it shows how the QMS interacts.”

Myth busted!

Although it might seem a very tempting proposition to fast-track the creation of a QMS by using the Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA)-based diagram (figure 2) on page viii of the ISO 9001 standard, it’s not a model to describe the organization’s QMS. What’s shown is how the QMS is supposed to operate in support of the business, not how the business operates. For example, in organizations that design innovative products, it is this process that precedes any customer demand, through sales, etc. In another case, a business may contract with a customer to perform design.

The key is that the organization’s leadership should determine how it wants the processes to operate in coordination to be most effective. Using what the ISO 9001 standard refers to as “The Process Approach,” the organization can focus its efforts on understanding how product and information should flow from one function to another (see figure 1 on page viii of ISO 9001).

Top tips

Create a large-scale (high-level) process map that demonstrates how requirements are processed from the inputs to the resulting outputs.

Use existing documentation – in whatever format and media it exists – to populate the processes as inputs, controls, etc.

Show who does work involved in the processes, who has responsibility, and, most importantly, who has authority. Create what else may be needed to fill gaps. Document processes. Experience shows that a process can be described adequately in approximately nine steps. Identify where measurements and/or monitoring of product or information is required and what is needed for that.

Be careful NOT to create a system of documentation, instead of a documented system. Ensure that the inputs and outputs align – specifically those that occur internally. Experience shows it is these internal interfaces that do not allow information to flow through the organization. It shouldn’t become an exercise in papering over the cracks that exist within the organization.

Section 4.4 (f) of ISO 9001 also mentions – for the first time in an ISO standard on quality management – the terms “risk and opportunity.” It is this and a sprinkling of those words in other places in the Standard that have set people off to create a mountain out of what really should be viewed in simple terms.

Myth alert!

“We’ll use a failure modes and effects analysis (FMEA) to document our risks.”

“We need a risk register and to rank risks as high, medium, or low.”

“We need to evaluate each process of the QMS for risks.”

Myth busted!

The use of the quality tool FMEA is an obvious choice for inclusion as a way to show compliance with this section of ISO 9001. The correct terminology for the tool is Potential Failure Modes, Effects and Criticality Analysis (PFMECA) and has been around since the 1980s, being widely adopted – with mixed results – by the automotive industry.

FMEA is used within the overall new product development process (often called Advanced Product Quality Planning), which may be applied to the product design (DFMEA) and product manufacturing process(es) (PFMEA). A cross-functional team analyzes (in this case) process and identifies potential failures (modes) and then applies ranking criteria such as the severity (S) of the failure, the occurrence (O), and the ability to detect (D) the failure, should it occur. The product of these rankings, S x O x D = the risk priority number (RPN), which is where the connection to risk occurs. It appears that people immediately rush to the conclusion that the tool should be used to evaluate the QMS processes.

This would entail a considerable amount of work – and is not what the ISO TC 176 committees imagined would be necessary, hence the commentary in the Annex A4 texts “Risk-based thinking” clarifying that a formal risk management process is not a requirement.

This non-prescriptive approach eschews the need for the organization to document even the risks it has identified, let alone assigning a ranking method, or any form of risk treatment. Annex B of the ISO 9001 standard – which is an informative reference – lists the other ISO standards that may be of use to QMS implementers in setting up or improving that system. No reference is made to any guidelines pertaining to risk. In fact, it’s the bibliography, tucked away on the last page (28), that includes ISO 31000 – the guidance on risk management and principles. None of the notes within ISO 9001 clauses refer to ISO 31000, so any thoughts about specific tools, lists, rankings, or applications of specific risk-based tools are NOT what is required.

Top tips

• Make a list of the interested parties and their needs/expectations. Record these in the management review records (9.3).

• Adopt a simple quality manual (see section 7.5) as a means to define a) the process, and their sequence and interaction as well as b) the scope of the QMS.

• Don’t overcomplicate the analysis of risk by ranking the results of the SWOT, etc.

• Consider the use of process FMEA if, and only if, you want better control over your (manufacturing) processes.

Leadership (5)

Leadership and commitment are key to any initiative undertaken by the organization, if it is to be successful. The implementation of an ISO-based QMS is no different in that respect. Commitment comes, for the most part, from the leadership’s active participation in the planning, creation, implementation, performance, and improvement of the QMS.

While it is – or should be – widely recognized that no implementation project is going to be successful without the active participation of the organization’s leadership, including setting aside the necessary budgets, progress reviews, and so on, it is perhaps paradoxical that few myths exist around this role – that of leadership. Few nonconformities are found and reported relating to much, other than the failure of personnel to adequately respond to the audit question: “How do you affect the quality policy?” or “What is the quality policy, in your own words?” or some variation of this line of inquiry.

Myth alert!

“Signing the quality policy is a demonstration of the commitment to ISO by the leadership.”

Myth busted!

Clearly, leadership is far more than putting a signature on some ‘executive order.’ We see world leaders do this regularly, yet totally fail at leading their respective countries through all manner of privation. The reasons are manifold.

Top tips

The leadership should be assigned roles as process owners, which involves the following:

• Know the requirements – including customer, regulatory/statutory (if applicable), and ISO 9001-related requirements

• Know the process – including the inputs, controls, resources (people’s roles, responsibilities, etc.), and outputs

• Know the performance – including the goals/objectives of the process, what is measured and what is monitored, and the current results

• Know the improvements – including what needs corrective action and improving

Use the above as the basis of meeting the requirements of “Management Review” (9.3) and focus on the third and fourth items relating to the management review agenda, as applicable to the specific process – presented by the process owner. Reference can be made to the results of the internal audits as validation of the details (the ‘story’) behind the process owner’s reporting.

The sub-clause of “Customer Focus” (5.1.2) is an interesting one, especially when viewed from a commercial perspective – or to put it another way: “It’s not quality at any cost.” If the aim of any organization is to satisfy a customer’s needs, then establishing those needs is predominantly the role of the sales and marketing functions. Prices and delivery are usually part of establishing needs and expectations, along with product/service specifications. Agreement usually comes in the form of a contract. The product or service is delivered and some attempt may be made to ‘survey’ the customer as to their level of satisfaction – with varying degrees of success or accuracy. But did the organization make any money? What was the cost of goods sold? The margin or mark-up? 25%? What is eroding that margin? The supplier rejects because the procurement/purchasing policy is to buy at lowest cost? The number of design engineering changes processed due to manufacturability/testability issues? The unrecorded costs of the processing associated with scrap, rework, and repaired product? Any warranty and recall costs? All these, and others, determine the actual revenue associated with doing business. Who is paying for that? To be truly customer focused, an organization needs to get these costs identified, accurately measured, under control, and improved – for survival.

Planning (6)

The first sub-clause of this section of the Standard is entitled “Actions to address risk and opportunities.” (6.1)

This requirement is intended to direct the organization to take those issues identified in considering the context of the organization – the (prioritized) results of a SWOT analysis plus the understanding of the needs and expectations of those interested parties – and put them into a plan that includes integration of the actions into the processes.

As previously discussed, the prevailing ‘silver tsunami’ of retiring, skilled, and competent workers is likely to put an organization’s ability to deliver good quality at risk. The organization should, therefore, plan to address this risk and identify what is to be done to mitigate the effects. Clearly, this is a risk that affects many organizations, so simply hiring replacement skilled workers isn’t a viable option. What to do?

Once commonplace, apprenticeships were a way of developing the next generation of skilled workers, but those programs had slipped into obscurity. Simply put, most organizations employ workers who might have been apprentices, but the training processes have not been maintained. Add to this secondary schools and many community colleges have cut back on those educational programs that prepared younger people for work and the organization cannot sit on its hands hoping someone else will step in. Furthermore, many organizations’ training processes typically only deal with the basics of onboarding and on-the-job training specific to the narrow focus of product/process tasks.

What’s needed is for the organization to develop a process, within the QMS, that will create the skilled workforce it will need in the future. Fortunately, experience shows that, because many others are in a similar boat, further education colleges and schools also are developing and offering the supporting educational programs in the much-needed development of skills.

This section of the Standard also contains a couple of guidance notes regarding risk treatment, including options for addressing risks, such as avoidance, elimination of sources of risk, changing the likelihood or consequences, sharing the risk, or retaining the risk by informed decision or even pursuing an opportunity through taking a risk. Opportunities are detailed as something an organization may identify as ‘new’: a process, product, technology, et’. It’s not clear that ‘new’ and ‘risk’ are often viewed as going hand in glove.

Quality Objectives (section 6.2) are required to be established at relevant functions, levels, and processes. This gives a great deal of latitude for the organization to think about the link to the quality policy (which itself is linked to the context of the organization) to establish the goals for the QMS. Before setting objectives, it is worth noting that they should be:

• Measurable

• Take into account applicable requirements

• Be relevant to product conformity and enhance customer satisfaction

• Be monitored

• Be communicated

• Be updated as appropriate

The quality objectives are also required to be maintained as documented information (but the Standard doesn’t say where they are to be documented or how).

Myth alert!

“We’ll set KPIs for all our processes and departments.”

Myth busted!

Defining KPIs in and of themselves is not likely to be most effective. It’s not unusual to have functions and departments select their own KPIs without consideration of the impacts on other areas of the organization or even the relevance of such KPIs.

By considering the basic tenets of quality management that relate to the era of total quality, and embrace the principles of product and process being done ‘On Time’ and ‘In Specification’, we get OTIS as a place to start flowing down objectives to the processes of the QMS. It is understood that in many cases, 100% is a nice idea but impractical – hence setting some level that is attainable and provides room for improvement:

On-time delivery of product as a goal might realistically become 95%.

First pass yield from a process might reasonably become 97%.

Having established these across the (core) processes, it follows that there may be an opportunity to set objectives at an individual level.

Top tip

When setting objectives, make them SMART. A (technical) member of staff might set the following:

• S = Specific:

“We want you to write technical blog articles to support our marketing on social media.”

“About 300 words for each article.”

• A = Achievable:

“Do you think you can do that in the coming year?”

• R = Relevant:

“The articles should cover topics such as A, B, C, and D.”

• T = Time based:

“We’d like one article every three months.”

Be selective on which processes have OTIS applied to them. It is easy to overwhelm people with multiple objectives. It might be tempting to set objectives for the document or records control processes, but these are hardly likely to directly affect the achievement of customer satisfaction.

The last requirement in Planning is devoted to planning of changes to the QMS, when the organization determines they are needed. There is a reference back to 4.4 and that changes need to be carried out in a planned manner. These should be viewed as changes identified at a strategic level, not the day-to-day changes that are covered within other clauses of the Standard, such as changes to customers’ requirements, product designs, and process controls.

It is well established that changes can be the source of problems without a robust plan. The requirements list the considerations the organization should make in its planning:

• The purpose of the change and consequences

• The availability of resources

• The allocation or reallocation of responsibilities and authorities

Support (7)

This requirement of the Standard deals with those parts of the QMS that support or are in place to enable the other processes to function more effectively. It includes:

Resources (7.1.1)

An organization must be selective at what it takes on, in the name of satisfying customers’ needs and expectations. People can move heaven and earth, but you have to give them time, tools, and a budget as a minimum. The resources are necessary for the whole of the QMS implementation and for process operation and control. These include the following:

People (7.1.2)

Despite the saying, “The factory of the future will be run by a man and a dog. The man is there to feed the dog and the dog is there to keep the man away from the machinery,” most organizations need people to do work to satisfy their customers’ demands and for the effective operation of the QMS. Oddly, having mentioned People, there is no reference to the other sub-clauses (7.1.6, 7.2, 7.3, 7.4) that go on to develop more on the theme of People…

Infrastructure (7.1.3)

Try as we might, it is a practical impossibility to produce a good-quality product, even with all the necessary people, without the appropriate equipment, power, computers, information, and so on. The infrastructure requirements to ensure product conformity should be identified and provided by the organization, including such items as process equipment, buildings, utilities, workspace, and services.

Environment for the Operation of Processes (7.1.4)

In step with the above, the work environment can also have an effect on product conformity. There is a note underneath the ISO 9001 requirement that defines typical environmental factors, such as noise, humidity, lighting, or weather. Others might include temperature, air quality, dust, etc. These factors must be managed.

Monitoring & Measuring Resources (7.1.5)

This requirement of ISO 9001 is possibly one of the most confused and abused, being open to interpretation, especially by those with minimal understanding of the topic. Commonly called ‘calibration’ and applied to equipment used to measure product characteristics and/or process parameters, the section starts by simply stating that measuring resources are provided to ensure valid and reliable results. It goes on to state that the resources provided are suitable for the measuring and monitoring activities and are maintained to ensure fitness for purpose. It doesn’t even mention calibration or verification! Interesting, isn’t it?

A sub-section called “Measurement traceability” points out that it may be a requirement (Customer? Regulatory?) or if the organization considers it essential to provide confidence in the validity of measuring, results can be calibrated, verified, or both.

Myth alert!

“All measuring equipment has to have a ‘calibration’ sticker on it to show the date calibrated, recall date, etc.”

Myth busted!

The problem with stickers is they do not stick, especially in some work environments. It is usual to have an identification number or similar on the device and use that to trace the record of calibration/verification.

Myth alert!

“Calibration must occur annually.”

Myth busted!

Calibration is really a function of use, for most common forms of gauges. Selecting and then sticking to a time-based calibration frequency can cause big (cost) issues that come from not calibrating frequently enough or too frequently. Use the data from periodic verifications to determine the calibration frequency.

“All measuring equipment must be calibrated.”

Myth busted!

There are three classes of measuring equipment:

1. Calibration/verification not required (for example, an engineer’s six-inch steel rule)

2. Verification before use (for example, a machine operator’s micrometer)

3. Calibration (for example, the equipment used to ‘master’ verification or perform measurements where confidence in results is paramount)

Myth alert!

“Calibration includes adjustment to correct the reading.”

Myth busted!

The act of calibration simply provides details of how the measuring equipment is performing compared to a known standard. If it is found to be performing out of specification/tolerance, then it may be a) still usable and b) incapable of being adjusted or c) replaced.

Myth alert!

“Uncalibrated equipment should be labeled ‘for reference only’.”

Myth busted!

Using such a label is not control! It is abdicating control. People need to know, if they use measuring equipment, whether they can have confidence in the results – especially if it helps them to determine the quality of the product they are processing.

Myth alert!

“Only equipment used for final inspection needs calibration.”

Depending upon the cost/value of the product to the organization, added to it through processing, it might be disastrous to discover that decisions made earlier about items tested and inspected may be out of specification at a final check. Relying only on final checks using calibrated devices can be expensive compared to intermediate checks with – as a minimum – verified devices.

Myth alert!

“Calibration is expensive.”

Myth busted!

Yes, indeed, it can be. However, not knowing the condition of the devices used for measuring and testing – especially if they are used to avoid rejection of product by customers or to suppliers – can cost a lot more.

Top tips

Don’t overcomplicate the control of measuring equipment by calibrating everything – it is wasteful and unnecessary.

In practical terms, the organization should simply consider this question: “If we make a measurement and can argue about the results (possibly rejections and associated unplanned costs) affecting customers, a regulatory body, or a supplier, then having our equipment calibrated is a good option – to ensure traceability to a known ‘master’ that is used nationally or even internationally. Internally, equipment may be verified using a known ‘master’ device to confirm it is working correctly. A simple record should be maintained, too.

The terms ‘calibration’ and ‘verification’ are often used interchangeably when describing how measuring equipment is controlled and maintained as fit for use. Calibration is the science of understanding how far from a true value the result from measuring a characteristic (product, process, etc.) is likely to be. The true value is correctly known as the ‘measurand’ and the process of measurement of a characteristic will be influenced in some manner by factors affecting the measuring results.

The calibration results of the device(s) used when measuring do affect the result and should be known before deciding if the characteristic meets the specification.

It is tempting to simply contract with a supplier of calibration services, such as a laboratory that is accredited to ISO/IEC 17025, and place a purchase order stating “calibrate to manufacturers’ specifications,” but this may not be sufficient. Carefully review the services offered – most labs provide a menu of services – to determine the one that is most (cost) effective.

Organizational Knowledge (7.1.6)

How does an organization know what it knows about how to satisfy customers’ needs and expectations for products and services? Clearly, it isn’t about specific technologies, processes, equipment, people, suppliers, etc. It must be a combination of all these and more. Reference to the notes at the foot of the page shows that ISO recognizes it is experience and based on sources that are both internal and external.

The Standard is pretty clear: Maintain the knowledge (it doesn’t say it needs to be in any form of documentation) and make it available.

Top tips

Many organizations have ways to capture what is learned during production of products. Operators make marginal notes on job cards/shop travelers or other documentation that accompanies the materials around the processes, as it is transformed. Similarly, if we consider those organizations that depend heavily upon the skills of their workforce, having some kind of mentoring program (see also section 6 comments) would be a way to ensure continuity of knowledge and also consider some form of succession planning.

With the advent of ‘Industry 4.0’ (or Fourth Industrial Revolution), which depends on nine interlacing technologies, clearly no organization is going to possess the relevant knowledge of these in the early days of adoption. It is likely, therefore, that external sources will need to be engaged, including manufacturers and suppliers of technology equipment, places of higher education, and government-sponsored entities, if the endeavor is to be successful.

Whatever course of action is taken, the intent is to minimize the risk of reinventing the wheel or doing the same thing and expecting a different result, which can befall such implementations.

There aren’t too many myths associated with this requirement, other than perhaps to attempt to document everything that isn’t likely to be a) simple or b) effective.

Use the QMS to manage any improvement opportunities, through management review and the change control requirements, and the next section of ISO 9001.

Competence (7.2)

With a strong link to the Operation requirements (section 8), specifically 8.3 and 8.5, the need for competent personnel is much more than simply training people. Training makes people dangerous!

Myth alert!

“Everyone needs training on ISO.”

Myth busted!

Few people need training – or indeed competency – in the ISO 9001 requirements. What’s most important is to understand the roles, responsibilities, and authorities of a job, know the process required, and know what to do in the event that everything doesn’t go to plan – how to deal with the process and any results that do not conform.

Myth alert!

“We ‘grandfathered’ people into their jobs.”

Things change and our grandparents didn’t keep up!

Myth alert!

“We have training certificates for everyone.”

Myth busted!

Training is just one of the options to help people become competent. A certificate doesn’t mean the person can apply what they learned, and some training just isn’t effective – so the certificate is meaningless.

Myth alert!

“We have new starters sign off with their supervisor that they understand their job.”

Myth busted!

It’s not a bad place to start, but without defining what the required competencies are and then demonstrating them, what’s the point of the signatures?

Competency is defined in the vocabulary document ISO 9000 as:

“ability to apply knowledge and skills to achieve intended results.” (3.10.4)

Why can’t the grandfathering card be played? After all, some people have been working at their jobs a long time.

Answer: There is a need to determine and demonstrate competency for personnel who perform work that affects quality. Although there are many theories surrounding how adults become competent, there are generally accepted phases1 that describe the progression:

1. Unconscious incompetence

2. Conscious incompetence

3. Conscious competence

4. Unconscious competence

It would be easy to assume that an experienced person is someone who has reached unconscious competence, and could be grandfathered into their job. That would be potentially a missed opportunity, partly because these are not concrete phases.

An article in a British motorcycle enthusiasts’ magazine discussed the background to why significant numbers of British motorcyclists were being killed in crashes on the roads. There were some shocking statistics, including that no one else was involved, just the bike and its rider. Another was the average age of the victims, which was 50 years. These were very experienced bikers, with many years of motorcycling informing their riding skills in addition to any tests they may have taken to receive a license.

What was causing these riders to get into these lethal situations? Analyzing the facts associated with each crash revealed that changes had occurred, which had affected the riders’ abilities, such as eyesight acuity, speed of reactions, and the power and capabilities of the motorcycles being ridden. All have an effect on the riders’ competencies, compared to their early years of riding. The final analysis of these events showed that just because someone attains phase 4 – unconscious competency – doesn’t mean they stay there!

Top tips

Awareness (7.3)

It might be obvious to many, but awareness isn’t the same as training or education. In today’s industrial environments, it is common practice to employ people to do specific tasks or activities that are part of a much more complex and complicated process. The scale of the production processes – take, for example, the UK’s Cross rail construction project, or building a car or ship. Large numbers of people with a narrow focus on specific work activities, which are all interlinked and can have significant impact on each other. Being aware of (quality) policies, the (quality) objectives, how their work affects the overall performance (quality) of the product, and the implications of not conforming to the QMS requirements are intended to provide greater ownership by individuals.

Communications (7.4)

Although it may be seemingly important that the organization communicates that it is using ISO 9001 to develop a formalized approach to its process controls, too much reference to ISO can be counterproductive.

In an effective implementation, most of the emphasis goes on ensuring people are aware of the fundamentals of the organization’s QMS, and why these are important to them in getting their work done, for regulatory compliance, to ensure customers’ needs are met, etc.

As with an organization that sets SMART objectives for its people, the communication of progress toward meeting those objectives, the ‘wins,’ the ‘losses,’ are all important to be known throughout.

Management should not treat performance like a game of Texas Hold ’Em poker. Everyone has a stake in the results, after all.

There are many ways that communication may take place of the reasons for an organization to use ISO 9001, including why the organization has chosen to formally define and implement a QMS, and ultimately become certified by a third party. This isn’t really “training” and 99% of personnel don’t need to know much of the “back story”. Far better to describe these through the use of ‘brown bag’ lunch meetings, newsletters, staff meetings, and other events – and no records are required!

Top tips

Communication is a two-way street. Tell people what is going on. Success breeds success. People rally to make improvements when given half a chance. Allow them to tell management what is important to them to know. Have them contribute gains, best practices, etc. Reward participation in events such as problem solving (using the ‘8D’ – 8 Disciplines – method. It is the eighth ‘D’: Reward the team).

Documented Information (7.5)

The requirement for the organization to include documented information as part of its approach to developing a QMS is in two distinct parts:

1. That documented information which is required by ISO 9001:2015, including:

• The scope of the QMS

• Quality objectives

• Quality policy

2. That documented information which is required by the organization to be included within its QMS.

This is to support the operation of the processes of the QMS. Once again, the Standard does not make it clear that there are other clauses that should be considered when attempting to determine what is required, in practical terms, to be documented. If we consider the Introduction, there are several reasons listed that provide background on which to base the consideration for creating and maintaining documentation.

Furthermore, if the “Needs and expectations of interested parties” are also understood, it should be seen that documentation may be required by customers, regulatory agencies (if applicable), and the personnel of the organization – to help them achieve objectives, as a training aid for people new to a job, to ensure control or processes, and to maintain knowledge of how work is accomplished. A lot of (good) reasons!

Myth alert!

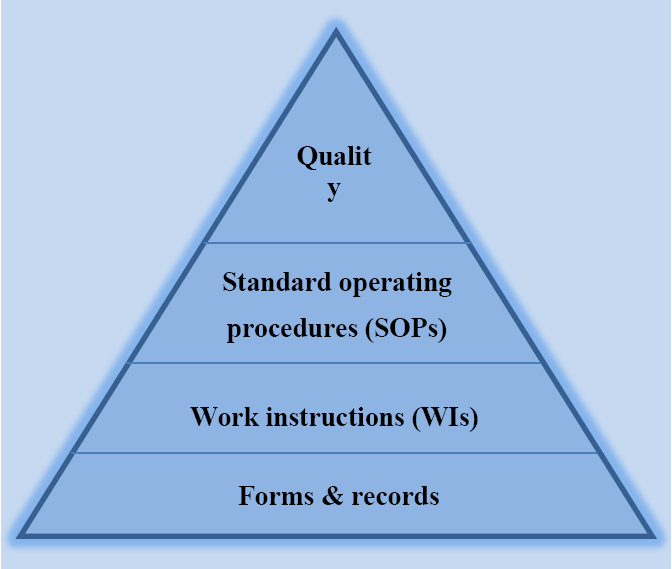

“We will structure our documentation like this diagram:”

Figure 2: Documentation structure

Myth busted!

In previous version of ISO 9001, it was only ever implied that a QMS had layers or levels of documentation. The 2015 edition allows an organization to create whatever documentation it sees fit and simply control it.

Myth alert!

“You should document your process so that if no one turns up for work, anyone can do the job.”

If, as the Standard suggests, we apply risk-based thinking to such a situation, it is unlikely that any organization will encounter this situation. The COVID-19 pandemic may have put a severe strain on the availability of people to a) work and b) be experienced in one or more of the basic processes of an organization. Hence, the need to write a sales or design engineering process down for inexperienced people is such a low risk as to be ignored. Write processes for your methods of operation, considering competent people are doing them.

Previous versions of ISO 9001, especially the very earliest editions from 1987 – 2000, referred to a variety of documentation types, specifically quality manuals, documented procedures, and, in relation to manufacturing processes, the provision of documented work instructions as a means to control processes. With the additional requirements to generate records, it was easy to see how the pyramid structure became the default interpretation – justified by an explanation that the standard operating procedures represented the ‘what’ had to be done and the work instructions represented the ‘how.’ This oversimplification of the requirements and need for documentation as a key component of the organization’s QMS became one of the biggest and long-lasting myths. It also served to drive away many smaller organizations that often saw the whole thing as a mountain of documents of dubious benefit.

The design of documentation can achieve a lot of features without creating a bureaucracy. The ‘smart design’ of documents for processes can include both instructions and a record that the process was completed – within the same document. Consider the place of technology. While paperwork may be cumbersome, technology solutions such as tablets, smartphones, and HDMI smart TVs bring their own challenges including opening up the organization to the risks of cybersecurity breaches and the associated costs.

Putting your drawings, specification, instructions, process descriptions, ERP, CRM, and countless data records in the Cloud can be fraught with complications if there is no one on the team who understands. ISO 9001 references “documented information” some 38 times. Consider how that documented information should also become “secured, documented information” and it can be seen that it is an extensive task. Much, if not all, of that documentation can be classified by the following:

• C – confidentiality

• I – integrity

• A – availability

These are the CIA triad of information security – a topic that we read about daily as adversely affecting large organizations. What is not always reported is the significant number of small/medium-sized organizations that also fall foul of cyber attacks – even those perpetrated by teenagers who did nothing but wipe all the calibration data off a hard drive.

Operation (8)

Operational Planning and Control (8.1)

In section 6 we reviewed the strategic planning required of the organization. In this requirement, the focus is on the planning at a tactical level.

Myth alert!

“Our processes are simple, we don’t need to plan.”

“We don’t have time to plan our processes.”

Myth busted!

It is the organization’s responsibility to determine the processes needed for the QMS and their sequence and interaction. In smaller organizations, this almost becomes the plan for the way that customer inputs are turned into deliverable products. Other organizations – often those that perform multiple, often more complex operations – use a ‘shop traveler’ or ‘operations sheet’ or similar, which defines each step or operation, in sequence, transforming the raw material into a completed product. It is also common for the quality control checks required to verify the product is correct to specification to be included on the plan.

More complex products, or where required by a contractual arrangement with a customer, sometimes dictate a more detailed document, which may be called a quality plan.

Requirements for Products and Services (8.2)

Myth alert!

“We call this ‘contract review’.”

“Our customer only gave us verbal instructions, there is no contract.”

“This is just about having a process for customer orders.”

Myth busted!

Quality, in all respects, begins with determining what the product being offered (for sale) is and what the customer wants, with the intent of coming to some form of agreement to supply! These requirements fit the convention of quoting, order processing, and change orders, in whatever form these take.

Customer Communication (8.2.1)

To avoid misunderstandings, and hence create opportunities for customer dissatisfaction, there must be control over communications, whether that’s regarding the organization’s website and claims for products, performance, availability, and so on. Similarly, how customer inquiries, quotes, ordering, and changes to these are handled must, as with any process, be controlled, avoiding errors.

Handling feedback to elicit the most accurate and useful information takes a special relationship and understanding – and is probably best handled by a few individuals. Of course, once the feedback is obtained, it is likely that the organization’s customers will expect to see the results of some action.

Although not prescribed by ISO 9001, providing plan B to take care of customers in the event that plan A didn’t work out is key to maintaining good, if not perfect, customer relationships.

Determination of Requirements for Products and Services (8.2.2)

The requirement touches on four basic factors:

1. Determining customer requirements

2. Determining requirements not stated by the customer but still necessary for use, where known

3. Statutory and regulatory requirements

4. Anything else thought necessary by the organization

Often, with innovative product designs, these factors are determined during development through market/customer research, some time before sales or agreement to supply the customer occurs. Indeed, a note indicates that the review may be of product catalogs or advertising materials.

Review of Requirements Related to the Product (8.2.2)

Before any commitment is made to supply customers, a review must be undertaken. Once again, the review isn’t simply a case of checking a customer order for the stated requirements – although that is important – but on receipt of a customer request for quote (RFQ/RFP), on receipt of an order, and when change orders are received by the organization.

The purpose of the review is to ensure that:

1. The product requirements are defined

2. The order and any previous offer (proposal, for example) are compared and differences resolved

3. The organization has the ability to meet the stated requirements

4. Records of the reviews and actions that arise are maintained

There are situations where organizations that take orders from customers verbally (telesales), and without any documents being used, cannot reasonably perform a review. In such cases, confirmation of the customer’s requirements is necessary. This can take the form of an order confirmation (email, fax, etc.) or by verbally confirming with the customer (which often is recorded). Design & Development of products and services (8.3)

Product design and development is where a lot of problems in manufacturing, with suppliers, and in the marketplace can be avoided with an effective process and relevant controls, responsibilities, authorities, etc.

Myth alert!

“The product design and development process cannot be measured.”

Myth busted!

The three key measurements of the NPD process are:

Quality, time, and cost

Myth alert!

“Design engineers need the freedom to be creative.”

While it is true that creativity and innovation are to be encouraged, these should still meet the three key measurements and also ensure that design for manufacturability, design for testability, etc. criteria are still met.

Myth alert!

“Following ISO will slow down the process.”

Myth busted!

The time spent in a well-developed new product more than makes up for the time/cost and aggravation associated with the inevitable post-release changes, warranty and customer dissatisfaction.

Time to market often is a huge part of driving new product developments and their introduction. The needs to wow the market, beat competitors, etc. are powerful factors. No one wants an underdeveloped product that, once released, takes unplanned resources (time/money) to resolve manufacturability issues, warranty costs, and potentially loss of market share through unsatisfied customer experiences – all of which should be added to the original development schedules/budgets for a true picture.

The product design and development process requirements of ISO 9001 are fairly simple and intended to ensure that the organization only designs products that can be produced, installed, and serviced without problems and that are safe for use – and customers get what they really want!

Often known as the new product development cycle (NPD or similar), the ISO 9001 requirements form a basic framework for controls that should enable not reduce creativity. The ISO 9001 8.3 requirements cover:

• Design Development Planning

• Design and Development Inputs

• Design and Development Outputs

• Design and Development Reviews

• Design and Development Verification

• Design and Development Validation

• Control of Design and Development Changes

Experience shows that there are a few key indications of how effective the design and development process is, and they are easily identified and measured:

• The number of post-release design changes (not resulting from customer inputs)

• The ‘on time’ and ‘on budget’ performance

• The retention of engineering staff

The last point is directly linked to the first; however, it is rarely seen in this light. Similarly, where parts of the new product under development include aspects that must be obtained from suppliers – particularly those working to specifications developed by the organization – early supplier selection is critical as it is proven that their input to the design is invaluable. Not only are changes avoided but also the high costs of supply disruptions from rejections, etc.

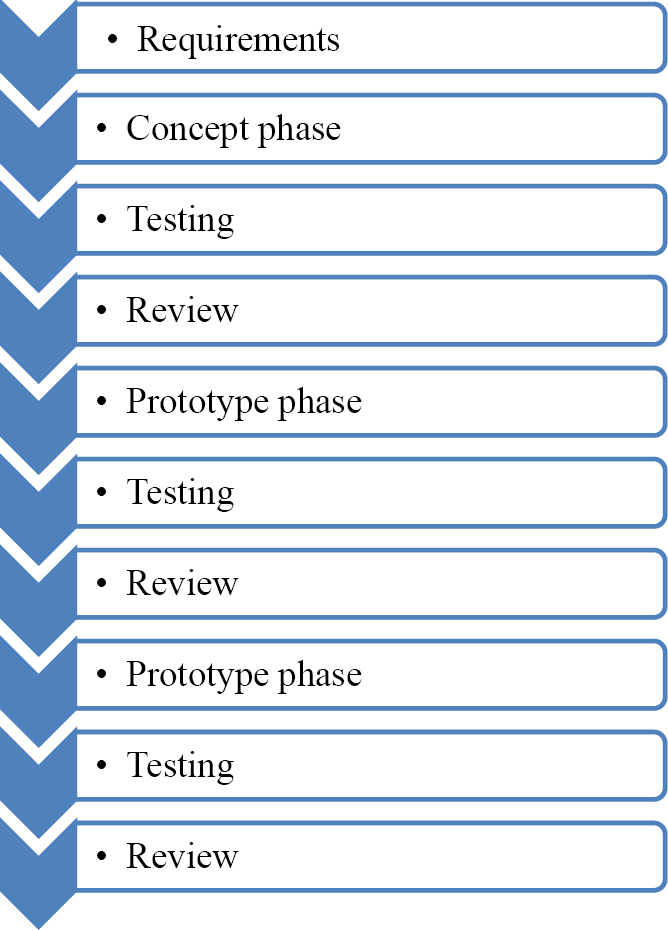

Let’s take a look at a typical new product design engineering process to understand the indicators of an ineffective process:

Figure 3: New product design engineering process

A robust product design and development process should release a set of product specifications to manufacturing and (as applicable) servicing organizations (whether those activities are performed internally by the organization or by its suppliers) that can be produced within the capabilities of those manufacturing and service processes. The product of the design engineering process is not unlike the product of the manufacturing process(es) in that it should not be necessary to ‘touch it twice’ to make it correctly (to specification) and it must be delivered on time and at the planned cost. Therefore, three key indicators of the effectiveness of the new product design and development process are:

1. Delivery to schedule

2. Development cost on budget

3. Post-release changes

This last point has been well studied because the cost of changing a product design, after release to production, is a significant factor. It is suggested that a fault found in the design phases might cost X to rectify, would cost ten times that value (10X) if detected in production, and 100 times more (100X) if found while in customers’ hands.

Often, it is necessary to process product design changes once the product has been released to be produced, either by the organization’s own manufacturing function or by its suppliers. Often, such changes are given to those design engineers who have recently qualified and been recruited, much to their chagrin.

Newly qualified product design engineers are probably under the impression that once they take a position in industry, designing new products is exciting and they will get to use their expertise, bringing innovative and creative ideas to light. In reality, they may be assigned (initially) to work on existing product design changes. This presents two challenges for these engineers:

1. It is often very difficult to re-engineer a product

2. They are often not sufficiently experienced to re-engineer products and this can be demotivating

A study of major Japanese new product introductions showed that the majority of changes to product designs occurred before release into the marketplace, and that few changes were undertaken after that. The results? Improved customer perception, lower warranty costs, happier service staff, and improved market image, to name a few.

Control of Externally Provided Processes, Products and Services (8.4)

Myth alert!

“An approved supplier list is required.”

Myth busted!

Most of us who are responsible for buying food, cars, services, and the things to make our lives tolerable have a way to evaluate suppliers of those things. We use criteria such as cost, product availability, service level, location, and so on. We rarely create even a mental list. ISO 9001 expects a similar, if more formal, process – and records of those evaluations against the criteria. But certainly no list, per se. For some organizations, a list of preferred suppliers might be useful, of course.

“Suppliers need to be audited.”

Myth busted!

For certain types of suppliers, an organization may wish to perform pre-award audits or even audits of any corrective actions undertaken after experiencing deliveries of a non-conforming product. However, ISO 9001 certainly doesn’t require such audits.

Myth alert!

“All suppliers should be ISO certified.”

Myth busted!

‘Let the buyer beware’ continues to apply in the supply chain regarding the use of suppliers with ISO certification. Care should be taken to ensure that the certificate is a) current, b) has a scope that covers the product/services being procured, and c) was issued by a certification body that is accredited by an IAF-member accreditation body. Details can be found at www.iaf.nu.

Care should still be exercised by the organization when considering suppliers with an ISO 9001 certificate, since it is not unknown for certificates to be issued that a) have inaccurate scopes (often including ‘design’ when no such work is undertaken) and b) the QMS isn’t compliant with the current version of ISO 9001! Bizarre but true in a small number of cases.

When selecting key suppliers, care should always be taken to assure that any certification is accurate and that the supplier organization is implementing a QMS that delivers product quality, as planned. An annual audit by a third party is too infrequent to detect changes in performance that can seriously affect the organization’s confidence in the supply chain. Certainly, process controls should be in place at even a basic level, which should prevent the added costs of the purchasers expending resources on supplier development.

Production and Service Provision (8.5)

Control of Production and Service Provision (8.5.1)

For an organization to produce a quality product (or service), it is generally held that the product-related processes must be carried out such that they are controlled. Although the requirements are seemingly simple, what is often missed is the concept behind controlling the production and service processes, which is to have ‘standard work.’ That is, each activity can be replicated over and over again, without variation, which may lead to a non-conforming product or process. A well-known example is a famous fast food restaurant chain, which has produced the same basic hamburger, serving billions by following the same process and methods, in every location, by thousands of people. Process control comes from one or more of the following:

• “Availability of documented information defining:

o Product characteristics, services provided, or activities

o Results to be achieved

o The availability and use of measuring and monitoring resources

• Implementing measuring and monitoring activities at appropriate stages to verify that process control or output criteria are met and acceptance criteria for products and services have also been met

• Use of suitable infrastructure and environment for process operation

• Appointment of competent personnel

• Validation and periodic revalidation of the ability to achieve planned results or the processes, where the results cannot be verified by subsequent measurement and monitoring

• Implementation of actions to prevent human error”2 (also known as mistake proofing and poka-yoke)

It is important to note that any one requirement should not be considered without reference to at least one other. This requirement of ISO 9001 specifically requires consideration of a significant number of others. Take the requirement for the “availability of documented information,” for example. The addition of the words “as applicable” might be considered ‘weasel words’ as they allow us to weasel out of having to comply! So, is it justifiable to not make some kind of documentation available to people performing product-related activities? A clue is in understanding the relationship to other ISO 9001 requirements that have influence on 8.5:

As noted previously, the people who are responsible for the control of a process may be assigned based upon competence (7.2). This may obviate the need for a document. However, we must not overlook the requirements from much earlier – the needs and expectations of interested parties. Surely there may be situations where:

• Customers will require some form of documentation to be used in production of what they are going to receive

• Regulatory agencies may require the organization to define documentation for control of processes

• Employees may benefit from having the process controls being documented to ensure effective training, for reference, for consistency, etc.

Furthermore, the use of documentation regarding production processes is a way of maintaining the contemporary knowledge of how the process is being operated – often called best practice.

Myth alert!

“All processes need work instructions.”

Myth busted!

Some form of work instruction is an option for controlling processes, but by no means a specific requirement. Customers may make it a requirement to gain confidence in the way their product is made. The organization also may decide – for many reasons including knowledge preservation, training, etc. – but work instructions are just one means of process control. A balance may need to be struck with the competency of the persons performing the work.

Myth alert!

“We test the first and last part to tell us if the others meet the specification.”

Myth busted!

Typically, where there is some (significant) volume of products being provided, the validity of taking a ‘first off’ and ‘last off’ is not an effective way to ensure all other products are to specification. Despite the Standard not clearly addressing the topic, if a process is to be operated and “in control”, concepts such as the causes of variation (common and special) must be understood and used to inform a suitable plan of inspections and tests.

Myth alert!

“Once we set the process up, as long as we are checking a few in production, we are good! There’s not much variation.”

Myth busted!

As with the previous myth, it is well established that even in control, processes vary over time and that this inexorable ‘drift’ needs to be studied. Knowing the three phases of installation quality, operational quality, and performance quality (IQ, OQ, PQ) is important in avoiding unforeseen quality issues and the attendant increased costs.

For some processes, the quality of the resulting output cannot be reasonably (economically or practically) tested or inspected. This requirement of ISO 9001 defines what the organization must do to ensure that an acceptable product is produced. For many, determining what processes fall into this category can be a challenge. In previous versions of ISO 9001, these processes were known as “special processes,” but even this didn’t adequately describe them – for such processes are quite common for organizations that perform them and not, therefore, considered special!

Which processes fall into the category of needing validation/revalidation? Some typical examples include:

• Gluing and bonding

• Welding, brazing and soldering

• Heat treatment and sterilization

• Plating, painting, and coating

• Torquing screw fasteners

As anyone who has attempted to repair a broken item at home (let’s say a vase) knows, following the instructions on the glue packaging is of vital importance to a good result. We are told to clean the mating parts, often with some proprietary degreaser/spirits/cleaner. The mating surfaces being joined might be roughened with sandpaper to provide a key for the adhesive. Of course, the temperature may also need to be between some values that represent a typical summer’s day.

Having prepared the surfaces, it may be necessary to coat the mating parts with the adhesive and allow it to cure (at least partially, when it is less tacky and dry to the touch). At this point, the mating parts may be required to be brought together and held, often under some pressure for a defined time. We also know it is tempting to test our newly created join in the precious vase to see if it is fixed! We might try to break the joint! How quickly our surprise turns to frustration when the joint does break and we have to start over! Oh, the temptation to check the joint once more…

Performing a test or similar on a sample from the process is a way to reduce the risk of failure in the other products being processed. This is still fraught with potential problems and can be wasteful too. We are left with imponderable questions about how representative the sample is. How is that validated? By the time steps have been taken to check that, the requirements for process validation have been met, so there is now no point in sacrificing a sample!

It is also worth considering that processes are subject to variation. Despite the fact that the ISO requirements do not mention it, for most organizations that produce any appreciable volume of products, their processes – particularly equipment – are subject to an amount of variation that can take the product out of specification.

Top tips

The idea of a quality (product) result that comes from gaining control over the inputs, resources, process parameters, and measurements, such that the output will be as planned and meets specification, isn’t an alien concept. Fast food providers do it daily – some really famous restaurants have been doing this millions and millions of times. No inspection after the fact! No one would buy a 1/4lb burger with teeth marks in it and a chunk missing.

The organization should strive to emphasize the control over processing to minimize the amount and type of ‘after the fact’ inspection because it is often too late in the process and, hence, the associated costs are higher than the already high cost of inspection. This previous list of examples are the usual suspects for this type of process control treatment, when – in all seriousness – all processes should be planned to be treated this way.

Identification and Traceability (8.5.2)

Myth alert!

“It is obvious what the product is from looking at it.”

Myth busted!

While it might be clear to most what type of product is being processed in terms of size, shape, weight, or other unique characteristic, identification also includes its status of activities like inspection and testing.

Myth alert!

“Our products have to be traceable to the raw materials.”

Myth busted!

This is a requirement of ISO 9001 that employs the ‘weasel words’ of ‘when it is necessary!’ This leaves the organization some latitude to decide when it deems necessary. It should be clear that – especially when products look similar – some form of identification may be necessary to prevent problems caused by mixing them. The methods used for identification can be diverse: identification on the part, location, container labeling are common options. It is not required when there is sufficient difference that there is no confusion about which product is which and people do not have to keep asking supervision!