CHAPTER 4: QUALITY – JUST WHAT IS IT?

It is appropriate to understand some basics that underpin the reason for the Standard being in existence. Since ISO 9000 has in its title the word “Quality,” defining ‘quality’ is important to understanding the context of a QMS. It is a word that can be a slippery concept to grasp.

There are all manner of definitions or descriptions of ‘quality’ – some conceptual, some esoteric, and some reasonably accurate. Definitions include “Doing it right first time” and “Selling products that don’t come back, to customers who do,” but for the purposes of understanding the Standard, we should look to the definition that is found in the “normative reference” for ISO 9001: the vocabulary document known as ISO 9000:

“degree to which a set of inherent characteristics fulfils requirements”

This definition is a classical one, but may be less than helpful to those who are new to the concept. Therefore, for the purposes of understanding this book, and the application of ISO 9001 to an organization, ‘quality’ is considered as:

“Doing what your customer tells you they want.”

No surprises, changes, or late or early deliveries: What they want, delivered on time. Simple, really!

Furthermore, it is going to be very necessary that the organization’s management has a clear and consistent understanding of this definition, because, without it, the rest of the implementation of the ISO 9001 requirements will be fundamentally flawed. The reasons will become clear later.

Furthermore, it is also important that key concepts which hinge on the use of the word ‘quality’ are also fully understood as distinct and separate – as well as being somewhat interrelated.

Those key concepts are:

• Quality control

• Quality assurance

• Quality management

• Total quality

Quality control – or “You can’t inspect quality into products!”

How ‘quality’ is achieved by an organization has been gradually changing since the Second World War, particularly with the trend to mass production techniques. It was traditional, in western manufacturing organizations, for quality control personnel – sometimes dressed in white lab coats – to inspect, check, and test products to see if they met the specification. Often, the most talented people from the manufacturing line were recruited to the quality control department, since they knew nearly everything about the manufacturing process; they also knew the problems that were manifest in the products. They were, simply, the best at finding the faults. This approach was costly and time consuming, and frustrated the people on the manufacturing line and their supervision. In some situations, the manufacturing departments would play games with the quality control people to meet production schedules and delivery dates, when products had been suspected of being rejects.

Worst of all, the quality control effort directed at the product wasn’t very effective in preventing defects getting to customers. A common assertion is that even 100% inspection (by people) is only 80% effective, at best.

To demonstrate this ineffectiveness, a simple test of the power of observation is used, where the reader has to count the number of times the letter ‘F’ appears in the following sentence:

“FINISHED FILES ARE THE RESULT OF YEARS OF SCIENTIFIC STUDY COMBINED WITH THE EXPERIENCE OF YEARS...” (Answer: 6)

Those who were alive during this era can often tell stories about their (or families’) experiences of the defects that afflicted consumer products!

Quality control is still an aspect of ISO 9001, albeit not performed the way as previously described. All processes need control(s), which may include measurement of process parameters and/or product characteristics and prove conformity to a specification or ‘quality.’

Quality assurance – Because assumptions are a poor choice!

Previously described in the Introduction, major purchasing organizations (mainly government entities such as departments of defense or food and drugs agencies) required suppliers to implement quality assurance programs. The requirements for these quality assurance programs were published in contractually binding documents that became the predecessors of ISO 9001.

The quality assurance program requirements emphasized that suppliers had to operate the basics for assuring the quality of the products they manufactured. These basics included having the supplier create and maintain:

• A quality assurance manual

• Documented procedures/work instructions

• Approved suppliers (list)

• Measuring equipment calibration

• Controls for a non-conforming product

• Training for personnel

• A quality manager/representative

• Inspection records

• Etc.

As the use of supplier quality assurance requirements (as they were known) became widespread, the top-level suppliers (tier 1, or primes) also started to pass them down through their supply chains. As a result, these lower-level suppliers were frequently required to implement and maintain a variety of quality assurance programs to meet each of their major customers’ requirements. Frustratingly, although there was substantial similarity across these customer quality assurance requirements, the supplier organizations had to maintain separate programs and documentation! Indeed, as mentioned previously, one supplier in the UK familiar to the author created and maintained 14 distinct quality assurance manuals to satisfy this demand, despite the fact that the product was a proprietary design!

Quality management – Quality doesn’t just happen!

In the closing years of the 20th century, there has been a gradual move toward the recognition that the achievement of ‘quality’ and customer satisfaction is one of the core purposes of any organization – whether that organization is for profit or not. With this recognition has come the understanding that management and control of the organization’s processes is what delivers that quality, from the process of developing and offering a new product into a market, taking an order from a customer, through to the delivery of that product and any post-sales services that also may be offered. What was required of a supplier organization as quality assurance has been enhanced and expanded to include not only the processes and activities thar are closely associated with making a product but also those that support and enable those product-related processes. This approach to quality is known today as quality management.

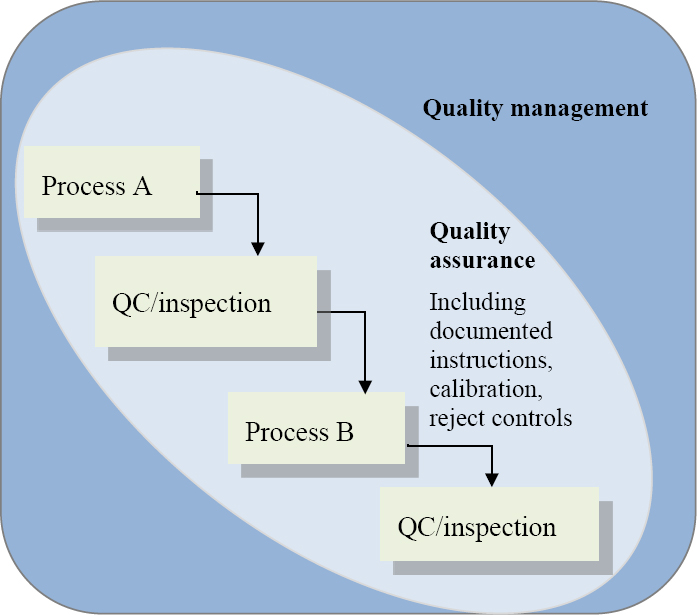

We can consider the relative scopes of the three ‘quality’ practices in the following manner:

Figure 6: The three ‘quality’ practices

We can see that quality control activities have a very specific application, often to inspect the output from a process before the next process is carried out. Quality assurance often focuses on the elements that can also go to make the quality control work more effective, for example calibration of equipment and inspection instructions, similarly with the relationship between quality assurance and quality management.

The ‘total quality’ movement

Between 1950 and 1980, a number of quality ‘gurus’ came to prominence. Their work was based on the principles that inspecting quality into product isn’t effective. These people shaped much of today’s approaches to quality and what has become known as ‘total quality management”:

• Phillip Crosby

• Dr. W Edwards Deming

• Dr. Armand Feigenbaum

• Dr. Walter Shewhart

• Phillip Crosby, known in part for his Quality Is Free book, formulated the “Four Absolutes of Quality”:

1. Conformance to Requirements

2. Right First Time

3. Price of Non-conformance

4. Prevention not Detection

Known as the father of modern quality, Dr. W Edwards Deming established many of the principles and practices of the contemporary approach to managing the (business) processes of an organization to produce a quality product. Deming is widely credited with leading the Japanese manufacturers in rebuilding their capabilities in the years after the Second World War. The adoption of Deming’s management principles by notables such as Toyota, Honda, Sony, etc. has been credited as the reason they dominate their markets with high-quality products.

Often thought of as being the granddaddy of the total quality movement, Dr. Armand Feigenbaum conceived the idea of ‘total quality control’ (TQM). In addition to identifying the costs associated with getting quality wrong (as did Crosby), Feigenbaum also highlighted the “hidden factory” – the name he gave to the extra work done in correcting quality problems.

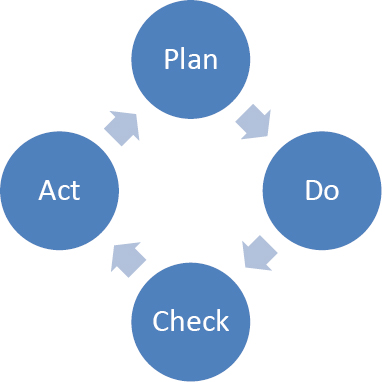

Dr. Walter Shewhart’s focus was on the use of statistics to control manufacturing processes. His understanding of process variations and the ability to use data was inspirational to Deming, who used this to formulate the widely used PDCA cycle, also known as the Shewhart Cycle. It is this PDCA cycle that forms the basis of the implementation diagram developed for ISO 9001:2015:

It is often suggested that none of these thought leaders in total quality management would have supported the implementation of the original ISO 9000 requirements to assure a quality product. The current version may, however, not be so anathema to them, since in the years leading up to the release of the 2000 version, the ISO Technical Committee members did much to consider and formulate how total quality management concepts might be incorporated. Moving from quality assurance toward quality management made it necessary to adopt a more encompassing description of how quality and customer satisfaction are systematically and effectively achieved.

For example, the ISO 9001 standard encourages organizations to consider seven quality management principles (found in 0.2 of the Introduction) when implementing their QMS.

These principles are:

1. Customer Focus

2. Leadership

3. Engagement of People

4. Process Approach

5. Improvement

6. Evidence-based Decision Making

7. Relationship Management

If we look at Deming’s 14 Principles, we’ll see that those at the foundation of ISO 9000 are surprisingly similar:

1. “Create constancy of purpose toward improvement of product and service, with the aim to become competitive and to stay in business, and to provide jobs.

2. Adopt the new philosophy. We are in a new economic age. Western management must awaken to the challenge, must learn their responsibilities, and take on leadership for change.

3. Cease dependence on inspection to achieve quality. Eliminate the need for inspection on a mass basis by building quality into the product in the first place.

4. End the practice of awarding business on the basis of price tag. Instead, minimize total cost. Move toward a single supplier for any one item, on a long-term relationship of loyalty and trust.

5. Improve constantly and forever the system of production and service, to improve quality and productivity, and thus constantly decrease costs.

6. Institute training on the job.

7. Institute leadership. The aim of supervision should be to help people and machines and gadgets to do a better job. Supervision of management is in need of overhaul, as well as supervision of production workers.

8. Drive out fear, so that everyone may work effectively for the company.

9. Break down barriers between departments. People in research, design, sales, and production must work as a team, to foresee problems of production and in use that may be encountered with the product or service.

10. Eliminate slogans, exhortations, and targets for the work force asking for zero defects and new levels of productivity. Such exhortations only create adversarial relationships, as the bulk of the causes of low quality and low productivity belong to the system and thus lie beyond the power of the workforce.

11a. Eliminate work standards (quotas) on the factory floor. Substitute leadership.

11b. Eliminate management by objective. Eliminate management by numbers, numerical goals. Substitute leadership.

12a. Remove barriers that rob the hourly worker of his right to pride of workmanship. The responsibility of supervisors must be changed from sheer numbers to quality.

12b. Remove barriers that rob people in management and in engineering of their right to pride of workmanship. This means, inter alia, abolishment of the annual or merit rating and of management by objective.

13. Institute a vigorous program of education and self-improvement.

14. Put everybody in the company to work to accomplish the transformation. The transformation is everybody's job.”4

Clearly, not all of Deming’s principles were adopted! ISO 9001 still maintains objectives (12) for the QMS, but many of the seven quality management principles mentioned in ISO 9001 can be seen to be aligned with Deming’s.

4 https://deming.org/explore/fourteen-points/.