CHAPTER 3: IMPLEMENTATION – A HOW-TO GUIDE

Once an organization has committed to implement a QMS based on ISO 9001, often the question arises: How? From what’s been described in earlier chapters, it should be clear that implementation of a QMS in compliance with the requirements of ISO 9001 isn’t simply ‘say what you do, do what you say’ or documenting a set of manuals, procedures, and work instructions to suit the requirements of the Standard.

Commonly asked questions voiced by those new to ISO 9001 implementation include, “How long does it take?,” “What does it cost?,” and “We’ve been in business for a long time, what else have we got to do to meet ISO?”

If we look at a tried and trusted methodology and describe the typical activities as well as key milestones involved to the point where the organization is ready to become certified, it will help any organization to answer – or at least estimate – what its particular implementation needs would be. If we take an analogy from the new product development process – the processes in which an organization launches a new product into the marketplace – we find that there are distinct similarities.

The phases and key action items and milestones can be represented diagrammatically, as shown on the following pages:

NEEDS ASSESSMENT (ALSO KNOWN AS A GAP ANALYSIS)

PLANNING AND PREPARATION

SYSTEM DESIGN AND DOCUMENTATION

SYSTEM IMPLEMENTATION AND AUDIT

SYSTEM REVIEW AND IMPROVEMENT

(The third-party certification process is covered in the following chapter.)

PHASE 5 – SYSTEM REVIEW AND IMPROVEMENT

Management review

Corrective action and improvement plans

Revised risks and opportunities

PHASE 4 – SYSTEM IMPLEMENTATION AND AUDIT

Process implementation

Product and process measurement and monitoring

Customer feedback

Results analysis

Internal audit

PHASE 3 – SYSTEM DESIGN AND DOCUMENTATION

QMS scope established

Process of the QMS identified, inputs, outputs, controls, criteria, etc.

Sequence and interaction established

Documented information identified – ‘maintained’ and ‘retained’ types

PHASE 2 – PLANNING AND PREPARATION

Competency/training requirements defined

Process ownership established

Detailed action list/timeline for implementation

Responsibilities and authorities defined

Quality policy and quality objectives established

Communications plan created

Budget and resource plan

SWOT analysis (context and interested parties)

PHASE 1 – GAP ANALYSIS

Three types of gap identified

Management commitment

ISO debriefing/overview session

Draft quality policy, quality objectives

Phase 1 – Gap analysis

Those organizations that decide to implement a QMS in compliance with ISO 9001 often have many of the requirements of the Standard in place – in some way, shape, or form simply through the needs of doing business and the innate ability of people to create processes, controls and documentation – for many reasons.

This fact, plus the commonly held belief (myth) that implementing ISO 9001 means “say (document) what you do, do what you say” (document), can lead organizations down the wrong path, leading to too much documentation being created, often in a format that is a bureaucracy to use and maintain.

Similarly, a ‘desk analysis’ may be performed, comparing what the organization has, in terms of ‘paperwork’ – only – against the ISO 9001 requirements. This can also give an incorrect view of the gap between what is required by the Standard and the organization’s current situation, since it doesn’t take into consideration actual practice and is, therefore, only a two-dimensional view of the QMS.

A fully effective gap analysis looks at the currently implemented practices of an organization in terms of:

• Something ISO 9001 requires that the organization practices, but may not be formal or fully compliant with the requirement

• Something ISO 9001 requires, and the organization isn’t practicing the requirement

• Something ISO 9001 requires and, whether the organization has formally defined a process or not, the implementation is not fully effective

To determine the type and extent of these gaps, an audit may be undertaken by someone fully competent in understanding ISO 9001 and effective auditing techniques. This second aspect of competency is of vital importance, since the auditor will be evaluating undocumented processes, etc.

Frequently, organizations choose to contract a qualified consultant to perform the gap analysis, since they often possess the necessary skills and experience to carry out the audit, provide the report, and debrief management in the nature and extent of the gaps, as a prelude to the next phase, which involves planning for implementation. It is not uncommon for management to have a (brief) overview of ISO 9000, including the background of its development, ISO 9001 requirements, and the certification process, given by the consultant after the gap analysis audit is performed.

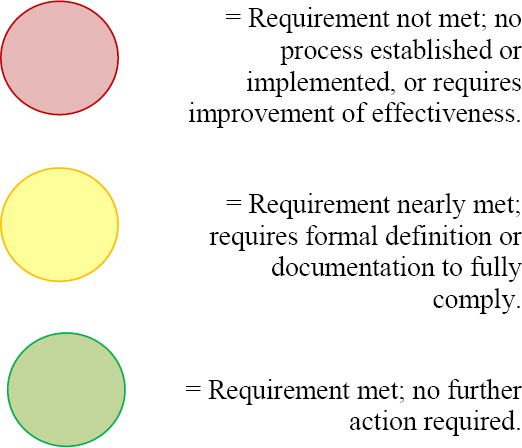

Throughout the management overview session, the findings from the gap analysis can be used as discussion points to better describe and explain what is required by the Standard and, if appropriate, to begin the creation of a detailed action plan. Some form of visual metaphor or graphic can be used to help effectively convey the state of compliance with ISO 9001, giving the organization’s management a clear picture, for example:

By way of a caution, it has been known to engage the services of an ISO 9000 certification body to perform this gap analysis, for many reasons. Its auditors should, after all, be familiar with the requirements of ISO 9001. Experience shows that this is not the most effective path to take, since the rules of accreditation restrict the certification body from consulting – including the delivery of on-site or in-house training at a client organization.

If the gap analysis is performed by someone different to the person who leads the management overview training event, the gap analysis report contents may be difficult to interpret. This, in turn, may result in discussions not being based on the fullest understanding of the actual practices.

Furthermore, since an IAF-accredited certification body cannot provide consultation services, the organization may not get the fullest benefit from its understanding of the ISO 9001 requirements, in the context of its processes, etc., during the debriefing. Being told where there are non-compliances with the Standard’s requirements is only part of the information the organization’s personnel need to know. They also need to know how to effectively close the gaps and what options they have, in terms of tools, techniques, and other resources. In short, the certification body auditor can only tell an organization whether it complies.

While undertaking an ISO 9001 management overview course, it would be appropriate to develop a clear action plan of activities, timing, and responsibilities to close the gaps. By whatever means this initial phase is accomplished, there should be several key deliverables:

• The commitment of top management to the implementation of the organization’s QMS – including the commitment to budget, timing, and personnel resources to support implementation

• A communications plan – what this means to the organization, the roles people will be playing, the time frame, descriptions of what is going to be new/different and how it affects people, for example internal audits, the purpose of ISO 9001 certification, and the process (if electing to become certified)

Phase 2 – Planning and preparation

The successful implementation of a QMS will require a detailed project plan of tasks, deliverables, responsibilities, and duration/timing. For each of the subsequent phases, the organization must ensure that all gaps previously identified are broken down into assignable activities with a clear result. By constructing a clear plan, there is a greater likelihood of management being able to set clear expectations, monitor progress, and address roadblocks. Furthermore, a better understanding of the duration and total resources required can be identified, which may translate to accurate budgeting and associated expenditure controls. In this phase, it is advisable for top management to be ascribed to ‘process ownership.’ Although the terminology isn’t found in ISO 9001:2015, the “Leadership” section can be seen to describe the role of “process owners” and, indeed, it is often a default situation for an organization to have a member of personnel hold responsibility in practice.

A simple project plan can be created as an Excel or Smartsheets file or similar, which can be an effective tool.

Whatever format is chosen, the plan for the creation and implementation of the QMS should clearly define:

• The person(s) responsible for accomplishing the task(s)

• The duration of the task(s)

• The deliverable(s) associated with the task(s)

• The timing of the task(s) relative to others

• A clear indication of the task(s) that are related (feed) or result from others, in a logical sequence

As each task is completed (or not), progress can be tracked, using traffic light (R/Y/G) status indicators. Those that fall into yellow (behind schedule) or red (stalled) status can be brought to the attention of management for understanding and resolution.

Frequent reviews should be undertaken by the personnel involved in the implementation to ensure the plan is kept updated and that any unforeseen activities are added, with the appropriate assignments, etc. As progress is made, the reviews will morph as each phase is undertaken.

Furthermore, it is possible to eventually transition the implementation project reviews into a platform for the management reviews required by ISO 9001.

On completion of the plan, approval should be gained from top management to proceed.

Phase 3 – System design and documentation

This phase is remarkably like the design and development phase for a product. The design of the QMS documentation is, in many ways, like a product. ISO 9001:2015 has almost no requirements in this regard and leaves it to the organization to determine what “maintained documented information” is required. This may include a consideration of the interested parties identified in the Context of the Organization section and the need to retain organizational knowledge, which is required in section 7.

The QMS documentation must be planned and have competent people to create it, and consideration must be given to how requirements that are applicable are going to be incorporated. Once designed, the documentation must be produced and assembled.

Good product design is also generally accepted to be something that is handed over to the people who are tasked with making it in a seamless manner. The design outputs are understood, well defined, and meet any applicable regulatory requirements, and, most importantly, can be implemented – or made – without causing problems. It is therefore important to involve the people who make the product to ensure requirements are defined in a way that makes life easy for them, by soliciting their input.

Rarely, and unfortunately, this comparison is never fully made, with the result that documentation causes problems for the people who have to use it. It has been stated, previously, that more attention is given to tiers or levels of documentation, or to the format, and to laying out things by ISO clause, than to the veracity of the information contained in the document.

It is of vital importance that the people who do the work contribute to the creation of whatever documents are really needed to perform work. It is often the case that having created a document describing how some work is to be carried out, it is ‘thrown over the wall’ to the supervisor to ensure training is carried out.

In creating documentation for the QMS, a good starting point is to inventory all and every existing document. Because these are documents that people find useful – even if not perfect – they can be used when completing another important step.

Mapping the processes of the organization is a very revealing part of the creation of the QMS and its documentation. Process mapping should be performed by those members of staff who are involved with each individual process, including the process owner, internal ‘supplier,’ and ‘customer’, facilitated by an impartial person. This person is primarily there to ensure that no one person takes a lead in describing the process, to ensure that the existing process is captured, warts and all. Capturing the process ‘as is’ is significant because opportunities to improve what happens often become obvious, particularly if care is taken to identify waste.

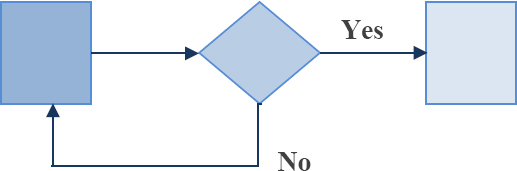

It is tempting to ‘flow chart’ a process, using the type of flow diagram used in determining the logic behind early computer programming. Apart from anything else, such a technique captures only what the ‘logic’ is, not what actually happens.

As discussed previously regarding the format of documentation, more effort may be wasted on the shape of the elements of the flow chart and their relative meaning, rather than gathering information on the actual process, possibly to the overall detriment of the result.

Capturing each process in its rough form can be best achieved by papering a wall of a meeting room, and having a team draw free form, using markers, sticky notes, postcards, etc.

Using examples of the existing documents that have been inventoried, the process maps can be populated. As issues are detected, consideration may be given to the contribution of any documents. For example, if a purchasing requisition form is used, but it is not clear how much information is needed – as a minimum – the buyer who receives it may have to halt the process, causing delays, etc. This should become apparent and a change made to the form design or a clear instruction given on what the minimum criteria are to be.

Once captured in rough form, consideration can be given to the final format for documents. With networked computers and applications such as Word, Adobe Acrobat and Microsoft Visio, the creation and structuring of the QMS documentation can be logically defined. Care should be taken, however, to ensure a convention for the naming of files and folders. When public access drives are used for QMS documentation, controls should be put in place to limit dumping of miscellaneous files, etc.

Furthermore, the controls necessary to allow access to read, without unauthorized editing, are also relatively straightforward to accomplish. One consideration is that unless all personnel who participate in the QMS have access to a computer/tablet to the documentation, some form of hard copy documentation may still be required by those people.

At some point in the development of the documented QMS, it will be important to put down the pens and begin the fourth phase.

Phase 4 – System implementation and audit

For a proportion of the processes, it will be business as usual, since the creation of the QMS has merely formalized what was already in place and working well.

For those other aspects of the QMS that are new or even substantially changed – reference back to the gap analysis results – it may be necessary to identify new or additional competencies. As has been stated previously, it isn’t absolutely necessary to train people on everything new or different. What should be established is whether anyone involved in performing a process – or part of it – is required to possess any additional/different competencies.

An example of a knee-jerk conclusion being drawn – which results in training – is when identifying candidates to become internal quality system auditors. While it may be obvious to suggest that most organizations have no one who possesses the necessary skills and experience as an internal auditor, sending a handful of people on a two-, three-, or even five-day auditor training course may not result in all the appropriate competencies being developed. At best, such training permits only a very basic level of audit skills.

Consideration must be given to some other basic or entry-level criteria for auditor candidates, onto which the auditor skills may be built. Even fundamental communications skills are often overlooked, as are interpersonal or soft skills, and even knowledge of the purpose and operation of other functions of the organization. The Standard on auditing, ISO 19011, gives excellent descriptions of characteristics auditors should possess.

When the processes of the QMS are demonstrating results, it will be necessary to perform internal audits.

As has been established, there are many and varied myths surrounding establishing and implementing an internal audit program. When faced with determining what and when to audit the organization’s newly minted QMS, there is a clue in the requirements of the ISO 9001 standard, 9.2.2. This states, in part, “that an audit programme (a number of audits) be planned, taking into consideration the importance of the processes…” Substituting ‘performance’ for ‘importance,’ we can develop an understanding of where and what to audit as a priority. In the context of the QMS, we can take risk as being higher with a process that doesn’t perform as planned and that makes it important if there is an impact on customers, regulatory compliance, or the cost of scrap, rework, etc. In the run-up to a certification audit, it would be entirely appropriate to select those processes/areas/activities of the QMS that are new to the organization, have been changed, and have a potential impact on customer satisfaction.

Phase 5 – System review and improvement

Following the period of implementation and auditing of the QMS, a point is reached when there is sufficient data regarding the performance of the processes. The next key milestone is to prepare and perform a review by the organization’s management.

From the performance data of the processes, it will be necessary to analyze this for trends, etc. This should be performed by the process owners, including the identification of corrective and improvement actions.

Despite ISO 9001 not requiring a meeting to perform a review by management of the QMS, experience has shown that this method brings a number of benefits. In many situations, the results of the internal audit process are not well understood as a review item. Since the internal audit process, for example, is new to the organization, it is common for the review to go through a detailed analysis of the findings, etc. without looking at what they really mean.

By looking at the following matrix, we can see that internal audit results can be viewed as validation of the QMS being effective in producing process results. Although a clear set of review topics is defined in ISO 9001, what is often missing is a ‘30,000-feet view’ of the QMS as a management tool to deliver results.

Table 1: Management Review in a Nutshell

PROCESS PERFORMANCE | INTERNAL AUDIT RESULTS | ACTIONS REQUIRED |

Meets or exceeds targets set | QMS being followed | Improvement of QMS? |

Meets or exceeds targets set | QMS NOT being followed | Improve QMS in line with practice |

Below targets set | QMS being followed | Corrective action required on process |

Below targets set | QMS NOT being followed | Corrective action on QMS |

Each process owner brings their analysis of their process performance, objectives, and action items to present and discuss with the other process owners.

From the review, opportunities to improve some aspect of the QMS should be weighed and the appropriate resources identified and assignments made to roll out the approved actions.

One of the outcomes of holding a review of the QMS is to confirm the readiness to undertake the certification audit. When all process owners can confirm they know their process performance, and have taken actions to correct and improve some aspect of the QMS, and that (importantly) the internal audits have validated the use of the QMS in controlling the processes to achieve results, the organization is substantially ready to undergo the stage 1 certification audit.

Once certified, the review of the QMS will be substantially similar, but part of the review will take into consideration the preparation for and results from subsequent certification body audits.

Once an organization achieves certification of its QMS, the focus should be turned from the basic implementation needs and toward maintenance and improvement. By referring back to the PDCA cycle diagram, we can see that the organization can employ key activities of the QMS in directing the maintenance and improvements required.

As stated previously, management review of the QMS is the cornerstone of the maintenance and improvement.