Chapter 9. The Art of War (Martial Art: Self-Control)

Those who win every battle are not really skillful…those who render others’ armies helpless without fighting are the best of all.

General Sun Tzu The Art of War [9.1]

The martial arts are called “arts” and not “sciences” because success or failure depends more on artful application than on any formula or equation. The central application of these arts is to the battle itself. It is with good reason that General Sun Tzu’s 2,500 year-old book is found on the shelves of many modern businesses today. Here in the twenty-first century, its ideas have become a treatise for combat in business, if not a primer for any conflict in life. But the good General did not originate the idea of winning without fighting. The concept goes all the way back to the Old Testament, “He that is slow to anger is better than the mighty” (Proverbs 16:32).

Fighting is synonymous with the contentious, evasive, and defensive behavior that you saw exhibited respectively by Ross Perot, Trent Lott, and Bob Newhart. Each of them demonstrated negative behavior that produced negative perceptions in their audiences, and none of them won his battle.

Contentiousness is the most damaging of these behaviors because it represents loss of control, the opposite of the desired objective of Effective Management. To achieve this positive subliminal perception, you must never react to tough questions with anger; instead always respond with firm, but calm resolve...which brings us full circle back to the Introduction where we set out with a one-word summary of all the techniques in this book: control.

Al Gore won his battle with Ross Perot without fighting. His interruptions caused Perot to lose control and become belligerent. Gore then rendered his opponent helpless by smiling…by using agility to counter force.

The Art of Agility

Agility requires artistry to succeed. Too strong a touch can overshoot the mark; too light can fall short. Martial art masters, athletes, and dancers, all of whom quest for physical agility, understand this all too well. They experience performances of sheer perfection and others of abject failure. The same can be true of verbal agility in the line of fire of tough questions.

Al Gore is a case study in point that ranges from his campaign and election in 1992, through his campaign and reelection in 1996, and all the way to his own run for the presidency in 2000. The progression of his performances in his mission-critical debates provides an object lesson that all the experience, all the knowledge, all the disciplined preparation and all the science in the world will be for naught without the artful application of agility, without self-control.

Force: 1992

A year before his masterful triumph over Ross Perot in the NAFTA debate, Al Gore used force against force instead of agility. In his first run for national office, Gore met Dan Quayle in a vice presidential debate on October 13, 1992, in Atlanta, Georgia. Quayle, who had been burnt four years earlier by the memorable Topspin of Lloyd Bentsen you saw in Chapter 7, “Topspin in Action,” was determined to not to allow history to repeat itself.

Quayle and his team decided to reverse the classic football maxim, the best offense is a good defense, by vigorously taking the offensive to Gore. Quayle prepared for the contest in extensive practice sessions with a formidable stand-in for Gore, then-New Hampshire Senator Warren Rudman, an aggressive gadfly whose subsequent autobiography was appropriately titled, Combat. Practice with Rudman made Quayle highly combative.

About a third of the way into the debate, Gore spoke of a talk he had had with some citizens who had lost their jobs. Then, he turned toward Quayle and asked:

Do you seriously believe that we ought to continue the same policies that have created the worst economy since the Great Depression?

Rather than answer Gore’s question, Quayle launched into an attack.

I hope that when you talked to those people you said: “And the first thing that Bill Clinton and I are going to do is to raise $150 billion in new taxes.”

Gore objected.

You got that wrong, too!

Ignoring the challenge, Quayle continued his attack.

And the first…that is part of your plan.

Gore objected again, shaking his head.

No, it’s not!

Raising his voice, Quayle repeated his charge, wagging his finger at Gore (Figure 9.1).

Figure 9.1. Dan Quayle wags his finger at Al Gore.

A hundred and fifty billion dollars in new taxes.

Quayle threw out his arms and shrugged his shoulders.

Well, you’re going to disavow your plan.

Gore tried to explain.

Listen, what we’re proposing…

Quayle stepped up the intensity.

You know what you’re doing, you know what you’re doing? You’re pulling a Clinton.

Several people in the audience hooted with laughter, as Quayle explained his terminology.

And you know what a Clinton is? And you know what Clinton is? A Clinton is, is what he says…he says one thing one day and another thing the next day…you try to have both sides of the issues. The fact of the matter is that you are proposing $150 billion in new taxes.

Shaking his head again, Gore objected to Quayle’s third statement of his charge.

No!

Quayle continued his assault.

And I hope that you talk to the people in Tennessee…

Gore fought back vainly.

No, we’re not!

Undeterred, Quayle pressed forward, speaking to Gore as if he was a schoolchild.

…and told them that…

Smiling wanly, Gore protested.

You can say it all you want but it doesn’t make it true.

On a roll, Quayle unleashed a crescendo of further accusations.

…[they were] going to have new taxes. I hope you talked to them about the fact that you were going to increase spending to $220 billion. I’m sure what you didn’t talk to them about…

Now Quayle turned away from Gore and looked straight into the camera to address the national television audience.

…was about how we’re going to reform the health care system, like the president wants to do.

Quayle culminated his tirade against Gore and Clinton with a strong Topspin to his own Point B.

He wants to go out and to reform the health care system…

For good measure, Quayle added one more layer of Topspin, to a WIIFY for the electorate.

…so that every American will have available to them affordable health insurance. [9.2]

Although Quayle won the exchange, he did not win the war. He could not slow the two powerful forces of George H. Bush’s inability to address the nation’s economic difficulties and Bill Clinton’s charisma that swept the Clinton-Gore team into the White House.

However, Gore could have done better in the debate. He could have employed the agility he would bring into play against Perot a year later. Instead, Gore met Quayle’s force with force by shouting back at his accuser’s charges, “You got that wrong!,” “No!,” “No, it’s not!,” and “It doesn’t make it true.”

Imagine if instead, when Quayle accused the Clinton-Gore ticket of planning to raise $150 billion in new taxes, Gore had neutralized Quayle’s charge with a Buffer of the Roman Column of their tax plan by saying,

Let’s compare our tax plan to yours.

Then, with the playing field leveled, imagine if Gore had answered,

Remember Dan, it was George Bush who said, “Read my lips… no new taxes,” and then raised them.

At that point, Gore could have even gone on to add Topspin with both a Point B and a WIIFY by concluding with,

The Clinton-Gore tax plan provides incentives for investment in job-creating activities…to get our economy going again.

In the end, however, it was the electorate, rather than Al Gore, that provided the ultimate Topspin.

Agility: 1996

Just as Quayle was able to reverse field, so did Al Gore when he and Bill Clinton campaigned for reelection four years later. Their opponents were two formidable politicians: Bob Dole, the veteran senate majority leader, was the Republican presidential candidate and Jack Kemp, the vice presidential candidate. Gore was to engage in a one-on-one debate with Kemp on October 9, 1996, in St. Petersburg, Florida.

Kemp would be a much more formidable opponent than the callow Quayle or the cantankerous Perot. Kemp had served nine terms in the House of Representatives and four years as Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, but his greatest claim to fame was as a professional football quarterback. He had played with the San Diego Chargers and the Buffalo Bills and led the latter to two American Football League championships. In all his public appearances, Kemp played the football hero image to the hilt, sporting an enormous, jewel-bedecked championship ring on his right hand for all the world to see. Moreover, he had developed a public persona as a charming, garrulous speaker.

Although Gore’s victory over Perot three years earlier had earned him new respect as a debater, he still carried the stigma, repeated ad infinitum by the late-night television comedians, of a stiff public speaker.

Once again, Gore and his team treated the debate as a major challenge and assembled at an offsite in Florida they called a “debate camp.” One of the strategies to emerge from their sessions was to level the playing field with Kemp by defusing the preconceived images of the football hero versus the wooden statue.

In his opening statement of the debate, Gore said,

I’d like to start by offering you a deal, Jack. If you won’t use any football stories…

Kemp took the bait. Seen in a television split screen, Kemp chuckled at the remark and then obliged even further by lifting his hand to pantomime throwing a football. His championship ring sparkled as he did. Meanwhile Gore struck an exaggerated deadpan expression (Figure 9.2).

Figure 9.2. Jack Kemp and Al Gore debate.

Then, Gore concluded his offer.

…I won’t tell any of my warm and humorous stories about chlorofluorocarbon abatement.

The self-deprecating humor produced not only a laugh from the audience, but agreement and capitulation from Kemp.

It’s a deal.

As the audience laughed louder, Gore broke into a big grin, and Kemp capitulated again.

I can’t even pronounce it. [9.3]

After this running head start, Gore went on to combat Kemp on both style and substance. Kemp, known for his verbosity, had three instances in which he lost track of the time, while Gore’s well-rehearsed answers were crisp and succinct.

Immediately after the end of the debate, CNN/USA Today/Gallup conducted a poll with a focus group of registered voters who had watched the debate. The first question they were asked was, “Regardless of which candidate you happen to support, who do you think did the better job in the debate, Al Gore or Jack Kemp?” The results: Gore 57%, Kemp: 28%. [9.4]

Once again, the Gore debate strategy, preparation, and execution, paid off. His double advantage over Kemp in the poll, combined with Clinton’s charismatic advantage over Dole, gave the incumbents the momentum to sweep to victory on Election Day. The die was cast. With his decisive conquests of Jack Kemp and, a year later, Ross Perot, Gore was now a debater to be reckoned with and, as a virtual incumbent, the Democratic candidate for president in the next election.

Agility and Force: 2000

In 2000, Gore’s opponent was then Texas Governor George W. Bush, a candidate saddled with the image of a man challenged by the English language. Despite Gore’s successes in the debate arena and his two terms in office, he could not shake the wooden label. The media and the late-night comics had a field day lampooning both candidates.

Notwithstanding the satire, Gore had the edge. By every estimate, he was expected to dominate the debates. In fact, the issue of The Atlantic Monthly that contained the James Fallows article in the previous chapter had on its cover a caricature of Gore baring feral fangs.

In their first debate, at the University of Massachusetts in Boston, Massachusetts, on October 3, 2000, Al Gore forsook the agility that had served him so well in the past and came out roaring like a lion. Fueled by his disciplined preparation (and very likely, a strong dose of overconfidence), Gore applied all his rhetorical strengths and accumulated knowledge against George W. Bush. Gore’s statements and rebuttals were filled with aggressive and divisive words like “wrong,” “not,” “differences,” “mistake,” and “opposite.” [9.5]

His manner was also combative, continually punctuated by condescending sighs, derisive head-shaking, scornful frowns, and disdainful eye-rolling (Figure 9.3).

Figure 9.3. Al Gore sighs at George W. Bush.

This arrogant behavior immediately boomeranged. The television broadcasters had a camera isolated on Gore for reaction shots. Their news directors took the output of this camera and edited all his disdainful expressions into a rapid-cut sequence. They ran the montage repeatedly in their local and national broadcasts.*

* You can see our version of this montage on the companion DVD, available at www.powerltd.com.

Public and professional criticism rained down on the vice president, implicating not only his haughty attitude, but the accuracy of his statements.

In response, Gore made a sharp about face and came out like a lamb in the second debate held on October 11, 2000, at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. During the 90 minutes, Gore expressed agreement with his opponent seven times on major issues, undershooting his intended mark by a country mile. Humbly, at the end of the broadcast, Gore even offered an apology for his exaggerations in the earlier debate:

I got some of the details wrong last week in some of the examples that I used, Jim, and I’m sorry about that. [9.6]

The most telling reaction to Gore’s docile performance came from a CNN analyst:

Whatever happened to Al the Barbarian? The man who knows better than anybody how to destroy an opponent with his mastery of the facts? Where was the clever repartee? Why did he let George Bush get away with so much without going in for the kill? Al Gore was emasculated by his handlers. He sat there as if he were embarrassed to be on the same stage and ashamed of taking up so much time. He let pass countless openings to unmask Bush as uninformed. He was so damned nice, he ended up drowning in his own honey. [9.7]

In reaction to reams of criticism like this, Gore reversed field again and swung back to his aggressive ways. In the third debate on October 17, 2000, at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, Gore went on the offensive. Remember that this is the very same town-hall format debate you read about in Chapter 7 when George W. Bush, left to his own devices in an answer to Lisa Kee, wandered off track and fizzled. In the following section, which occurred earlier in the debate, you’ll see Gore’s most pronounced attack and, more important, how Bush handled it.

The moderator, Jim Lehrer of the PBS News Hour asked:

Would you agree that you two agree on a national patient’s bill of rights?

A revved-up Al Gore replied emphatically, “Absolutely not,” and then went on to discuss a proposal pending in Congress called The Dingle-Norwood Bill, which would provide legislation on HMOs. Gore then went on to say:

And I specifically would like to know whether Governor Bush will support the Dingle-Norwood bill, which is the main one pending.

Lehrer said:

Governor Bush, you may answer that if you’d like. But also I’d like to know how you see the differences between the two of you, and we need to move on.

The Governor rose from his seat and began to address his answer to the town-hall audience.

Well, the difference is that I can get it done. That I can get something positive done on behalf of the people. That’s what the question in this campaign is about…

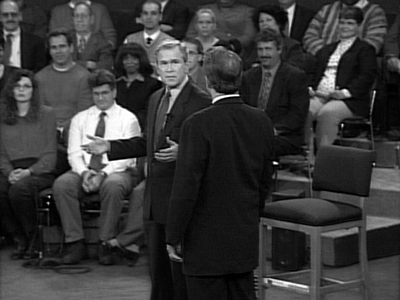

As Bush continued his answer, Gore stood up, and started to walk across the stage, directly toward his opponent, almost menacingly. Unaware of Gore’s move, Bush continued:

…It’s not only what’s your philosophy and what’s your position on issues, but can you get things done?

In the middle of his statement, Bush turned to see Gore approaching (Figure 9.4).

Figure 9.4. Al Gore approaches George W. Bush.

Bush paused for a beat, then nodded at Gore and smiled, evoking titters from the audience. Then, Bush turned back to the audience and said:

And I believe I can.

The audience titters gave way to laughter. Gore stopped in front of Bush and forced a broad smile that stood in sharp contrast to his rigid body language and insisted:

What about the Dingle-Norwood bill?

Lehrer interceded.

All right. We’re going to go now to another…

Bush said:

I’m not quite through. Let me finish.

Lehrer acceded.

All right. Go…

Bush went on:

I talked about the principles and the issues that I think are important in a patients’ bill of rights. It’s kind of [a] Washington, D.C. focus. Well, it’s in this committee or it’s got this sponsor. If I’m the president, we’re going to have emergency room care, we’ll have gag orders, we’ll have direct access to OB/GYN. People will be able to take their HMO insurance company to court. That’s what I’ve done in Texas and that’s the kind of leadership style I’ll bring to Washington. [9.8]

George W. Bush did to Al Gore what Al Gore had done to Ross Perot: He countered hostility with agility and neutralized his opponent. To add insult to Gore’s injury, Bush, with a virtual free pass from the moderator, concluded his exchange with strong Topspin; an advantage he neglected to take later in that same debate in his exchange with Lisa Kee.

A The Wall Street Journal/NBC News poll about the effects of the debate on public opinion gave George W. Bush a seven point advantage over Al Gore. [9.9]

How did this upset occur? How was the underdog able to give the favorite a run for his money? The answer lies in a dynamic that often occurs in a contest of mismatched opponents: lower expectations. All the underdog has to do is show up and not foul up. All George W. Bush had to do was avoid mistakes; anything less than a total thrashing by Gore would be a success for Bush. In fact, the Bush team, intentionally or not, presaged its debate strategy by naming its 2000 campaign jet airplane, “Great Expectations.”

The debates were Al Gore’s to lose and, given his previous successes and his own great expectations…he did. Of course, George W. Bush did become the president in an election so tight the Supreme Court had to decide the disputed vote in the swing state of Florida, but imagine if Al Gore had dominated the debates as he was expected to?

In the first debate, Gore abandoned agility and became the assailant. In the second, he over-compensated the opposite way into passivity. By the third, in trying to reassert his power, he overshot his mark, lost his touch…and control.

Gore beat his two previous opponents with the agility of a judo master. He made Ross Perot the assailant by provoking his volatile temperament with interruptions, and he threw Jack Kemp off balance by puncturing his jock charm with self-deprecating humor. When Gore made his forceful “in-your-face” move on George W. Bush, Gore became the attacker. When Bush smiled at Gore’s menacing approach, he turned Gore’s own former weapon against him; the weapon you would do well to learn…agility counters force.

Agility and Force: 2004

By the time President George W. Bush and Senator John F. Kerry met for the first of their three scheduled debates, each of them had staked out a reputation as a formidable debater. The president by virtue of his victory over Al Gore four years earlier; and the senator, a champion debater since his student days at St. Paul’s prep school and Yale University, had honed his skills on floor of the U.S. Senate for 20 years. The two men were, by most rhetorical standards, considered equals.

Moreover, the grueling political campaign of that summer…one of the most polarized in the history of presidential elections…had etched their diametrically divergent platforms indelibly. Both of them had sharpened their positions on key issues and had delivered them many times over. Both of them were also highly skilled at Topspin: repeatedly making calls to action by asking for the vote, their Point B, and repeatedly pointing out how that vote would bring security, tax relief, health care, and the like, to the electorate, their WIIFYs. However, there were several other factors in play in their debates, having to do with agility and force.

After nearly half a century, the accumulated intelligence about televised political debates had grown to a canon of enormous proportions. The respective Bush and Kerry committees, determined to learn from history and avoid mistakes, negotiated for months to establish a set of intricate guidelines. They finally came to terms in a Memorandum of Understanding that ran 32 pages and covered everything from the sublime, the rules of engagement, to the ridiculous, their notepaper, pens, and pencils.

Echoes of history reverberated behind every stipulation: control of the studio temperature to avoid a repeat of the perspiration that betrayed Richard Nixon; control of the town-hall audience microphones to avoid a follow-on question like that of Marisa Hall; a system of warning lights (green at 30 seconds, yellow at 15 seconds, red at 5 and flashing red to stop) installed on each lectern to avoid the difficulties Jack Kemp had with time; and a ban on television-camera reaction shots to avoid images of a candidate looking at his wristwatch as did George H. Bush or showing disdain for his opponent’s remarks as did Al Gore. Every aspect of the debates was covered in excruciating detail, right down to the exact positions and heights (50 inches) of the podiums.

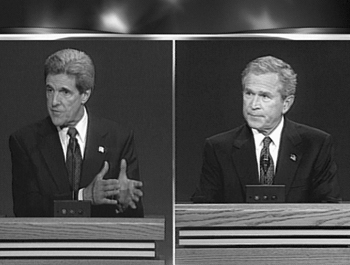

This latter specification was to boomerang against George W. Bush in the first debate on September 30, 2004, at the University of Miami in Coral Gables, Florida. The podiums were to be of equal heights, but the candidates were not. John Kerry is 6′4", and George W. Bush is 5′11", which caused the incumbent to hunch over his lectern, while the tall senator stood erect and free of his. The presenter behavior/audience perception dynamic reared its forceful head and struck George W. Bush between the shoulder blades: The President looked challenged, and the challenger looked presidential (Figure 9.5).

Figure 9.5. John Kerry debates George W. Bush.

The timing system also worked against the incumbent and for the challenger. With the warning lights in constant view of the 62.5 million people in the television audience, the president, on several occasions, ran out of things to say while the yellow light was on, leaving 15 precious seconds unused, during which he might have added a supporting point. Worse still, when he stopped speaking, his voice hung in midair, making him appear uncertain.

The most glaring of these instances came late in the debate, in his response to a question about his relationship with Vladimir Putin, the Russian president. The American president started his answer briskly, but half way through, he began to slow down and to punctuate his words with long pauses and repeated “Uhs.”

I’ve got a good relation with Vladimir. And it’s important that we do have a good relation, because that enables me to better…uh…comment to him, and to better to discuss with him, some of the decisions he makes. I found that, in this world, that…uh…that it’s important to establish good personal relationships with people so that when you have disagreements, you’re able to disagree in a way that…uh…is effective. And so I’ve told him my opinion.

I look forward to discussing it more with him, as time goes on…uh…Russia is a country in transition… uh…Vladimir is…uh…going to have to make some hard choices. And I think it’s very important for the American president, as well as other Western leaders, to remind him of the great benefits of democracy, that democracy… uh…will best…uh…help the people realize their hopes and aspirations and dreams. And…uh…I will continue working with him over the next four years.

When the president concluded, the yellow light was still lit.

Conversely, the senator, who had developed a reputation as being long-winded, was able to control the length of his statements with the timing lights, a skill he had sharpened in four full 90-minute practice sessions just prior to the debate. As part of his practice, he also learned to punctuate his statements by finishing them succinctly, often with Topspin, just as the red light lit.

John Kerry also used Topspin to punctuate…and puncture…one of his opponent’s primary rhetorical themes. Throughout the campaign, Bush had disparaged Kerry’s record of shifting policies and repeatedly labeled them “flip-flopping.” In that first debate, the president hammered home this theme at least eight times, accusing the senator of “changing positions,” “inconsistency,” “mixed signals,” or “mixed messages,” culminating in one forceful fusillade:

You cannot lead if you send mixed messages. Mixed messages send the wrong signals to our troops. Mixed messages send the wrong signals to our allies. Mixed messages send the wrong signals to the Iraqi citizens.

One of John Kerry’s primary slogans, repeated many times over on the campaign trail, was that the “W” in George W. Bush’s name “stands for wrong. Wrong choices, wrong direction for America.” When the senator’s turn came to reply to his opponent’s fusillade, he countered it with a swift burst of Topspin:

It’s one thing to be certain, but you can be certain and be wrong.

At another point in the debate, Kerry used Topspin again to counteract the flip-flopping label. He did it during an exchange that began when the president seized the opportunity to once again remind the 62.5 million viewers about the senator’s bete noir that you read about in Chapter 7.

He voted against the $87-billion supplemental to provide equipment for our troops, and then said he actually did vote for it before he voted against it. Not what a commander in chief does when you’re trying to lead troops.

The moderator, Jim Lehrer, gave the floor back to John Kerry,

Senator Kerry, 30 seconds.

Kerry began his rebuttal by taking responsibility.

Well, you know, when I talked about the $87 billion, I made a mistake in how I talk about the war…

Then he concluded with Topspin,

…But the president made a mistake in invading Iraq. Which is worse?

The Topspin worked: The statement was played and replayed as a sound bite on the television news programs. Unfortunately, in another exchange just a few moments later, the senator reverted to form when Jim Lehrer asked him:

Are Americans now dying in Iraq for a mistake?

No.

By contradicting himself, in effect, he admitted to his tragic flaw, and shot himself in the foot. [9.10]

George W. Bush almost shot himself in the foot with the recurrence of the specter of the dreaded reaction shot. The television broadcasters…including Fox News, the openly pro-Bush cable channel, that provided the pool cameras for all the networks…got around the campaign committees’ prohibition on such shots by using a split screen. For most of the debate, all the channels showed both candidates, so that, while one was speaking, the other’s reactions were clearly visible.

These split screens proved to be George W. Bush’s own bete noir. In an eerie echo of his own debate with Al Gore four years earlier, it was now the president who repeatedly expressed displeasure while his opponent was speaking. This time, it was with disdainful scowls, impatient frowns, and angry grimaces (Figure 9.6).

Figure 9.6. George W. Bush scowls at John Kerry.

In an equally eerie echo, the television cameras captured Bush’s scorn, but this time, it was the Democratic party that leapt to the fore: Within 24 hours after the debate, it posted on its website a page called “Faces of Frustration,” which linked to a 43-second video sequence of 14 rapidly cut shots of George W. Bush’s peevish looks.*

* You can see our version of this sequence on the companion DVD, available at www.powerltd.com.

The public reaction to the president’s behavior was instant and dramatic. According to a Gallup Poll taken immediately after the debate, Kerry won by 53% to Bush’s 37%. [9.11] Four days later, Gallup reported that Kerry, who had fallen behind Bush in the national preference polls since the Republican National Convention in early September, had pulled even at 49% to 49%. [9.12]

According to virtually every knowledgeable political opinion, Bush’s negative behavior had damaged his own cause. One political analyst said, “The Bush Scowl is destined to take its place with the Gore Sigh and the Dean Scream.” [9.13] The latter reference to Howard Dean’s impassioned concession speech following his loss in the 2004 Iowa Caucuses that was widely attributed to be the cause of the subsequent failure of his candidacy. The Scowl, The Sigh, and The Scream are all counter to the biblical advice to be slow to anger.

It was the very office he was seeking to renew that tripped up George W. Bush. As the son of a president and the grandson of a senator, he managed his first term as a political aristocrat. During the 2004 campaign, a flood of books hit the market with insider accounts of the Bush Oval office. Many of them depicted him as a man living in an insulated capsule, constantly surrounded by phalanxes of protective aides who reverently called him “Sir,” and rarely disagreed with him. Those who did were met with his disdain or wrath. In a way, he had been functioning as an omnipotent CEO of the nation, in much the same manner as Ross Perot had functioned in his business.

Furthermore, George W. Bush had held fewer press conferences than any other president in history, thereby minimizing his exposure to tough questions from the press. Finally, all his appearances in his campaign for reelection were to pre-screened by audiences who were already ardent supporters. By the time he stepped into the arena with John Kerry, George W. Bush was a man unaccustomed to being challenged. Therefore, when Kerry took him to task in front of a huge television audience, much as Al Gore had taken Ross Perot to task, Bush, like Perot, met force with force.

For the second debate, George W. Bush turned back to agility for damage control. On October 8, 2004, he met his opponent at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri. One of the questions was about nuclear proliferation. Senator Kerry, who answered first, was critical of the president’s policies.

…the president is moving to the creation of our own bunker-busting nuclear weapon. It’s very hard to get other countries to give up their weapons when you’re busy developing a new one. I’m going to lead the world in the greatest counterproliferation effort. And if we have to get tough with Iran, believe me, we will get tough.

When President Bush’s turn came, in an attempt to lighten matters, he said:

That answer almost made me want to scowl. [9.14]

President Bush turned to agility again in their third and final match on October 13, 2004, at Arizona State University in Tempe, Arizona. The moderator, Bob Schieffer of CBS, asked both candidates a question about their wives.

What is the most important thing you’ve learned from these strong women?

George W. Bush responded:

To listen to them.

The audience laughed. Then, the president used the laughter to defuse the still-lingering after-effect of his peevish performance in the first debate by adding,

To stand up straight and not scowl. [9.15]

However, that second debate in St. Louis produced yet another eerie echo of history. This time, the resonance was with Al Gore’s notorious “in-your-face” move during the town hall format four years earlier. In the 2004 version of the same format, one of the citizens in the audience, Daniel Farley, asked both candidates a question about reinstituting the draft. The president answered first, and then the Senator took his turn. Mr. Kerry concluded his answer with the following words:

We’re going to build alliances. We’re not going to go unilaterally. We’re not going to go alone like this president did.

The moderator, Charles Gibson of ABC News, said:

Mr. President, let’s extend for a minute…

Suddenly, George W. Bush jumped from his seat, thrust his forefinger into the air, and started striding toward Gibson, saying,

Let me just—I’ve got to answer this.

Gibson, trying to set up a rebuttal, said:

Exactly. And with Reservists being held on duty…

Overriding Gibson’s words, Bush continued his aggressive stride. As he did, he thrust out his left arm and gestured toward Kerry.

Let me answer what he just said, about around the world.

At that moment, the television image cut to a reverse angle to show a startled Gibson (and equally startled audience members behind him) with Bush’s agitated hand waving up and down in the foreground (Figure 9.7).

Figure 9.7. George W. Bush approaches Charles Gibson.

Trying to assert control of the debate, Gibson said,

Well, I want to get into the issue of the back-door draft…

Overriding Gibson’s words again and gathering momentum, Bush abruptly turned his back on the moderator and swung around to address the town-hall audience, his voice ringing with scorn.

You tell Tony Blair we’re going alone. Tell Tony Blair we’re going alone. Tell Silvio Berlusconi we’re going alone. Tell Aleksander Kwasniewski of Poland we’re going alone. There are 30 countries there. It denigrates an alliance to say we’re going alone. [9.16]

To add insult to injury, the very next night, Saturday Night Live, the NBC television comedy series, reinforced the incident. In its satirical version of the debate, the actor portraying Bush excitedly jumped off his stool and rudely interrupted the actor portraying Gibson.

Saturday Night Live, however, is an equal opportunity satire provider. The comedians also gave John Kerry a dose of their barbed wit. In that second debate, the senator used the phrase “I have a plan…” 13 times, and so in that same program, the actor portraying Kerry used the phrase repeatedly, too.

However, the actual George W. Bush had only that one forceful outburst during that second engagement. The rest of the time, he contained his aggressiveness and petulance. In fact, he was a man transformed from the first debate. Every time he spoke, he did so more with animation than antagonism, and every time the reaction camera showed him listening to his opponent, George W. Bush was attentive but impassive…no frowns, no scowls.

The strategy worked. The Gallup Poll taken immediately after the second debate showed Bush did better in the match…but Kerry did better still with 47% to Bush’s 45%. [9.17] Four days later, Gallup reported that Kerry still maintained a slight edge in the preference polls with 49% to Bush’s 48%. [9.18]

In their third and final debate, the two candidates returned to stand up…straight this time…behind their lecterns, at a precise distance (10 feet) from each other. The separation was stipulated in the prearranged Memorandum of Understanding so that there would be no more “in-your-face” moves on each other. (Apparently, Charles Gibson was exempted as fair game.)

To further reduce the potential for conflict, the agreement also stipulated that the candidates could not question each other directly, but that did not inhibit them in the least. With this one last chance to win in the rubber match, the two men debated toe-to-toe, sharply attacking each other’s policies, past performances, and even personalities. They bounced their attacks and counterattacks at each other via the moderator, Bob Schieffer, via the studio audience at Washington University, via the television audience of 51.2 million viewers, and even out into the ether.

Throughout the debate, they hurled bitter names, labels, and charges at each other with fierce intensity. Bush accused Kerry of “exaggeration,” being “dangerous,” making “outrageous claims,” and of being “a liberal senator from Massachusetts.” Kerry accused Bush of “failure,” being “wrong,” “misleading,” a “problem,” and of being “the first president in 72 years to preside over an economy in America that has lost jobs.”

However, all the hostility was in their words alone. John Kerry, ever the polished debater, maintained the same calm, cool, poise and sturdy confidence he had exhibited in the first two debates. George W. Bush repeated his controlled demeanor of the second debate by being animated physically without being antagonistic. In fact, on several occasions, he added smiles to his repertory. One of them, while he was attacking his opponent’s health care plan:

I want to remind people listening tonight that a plan is not a litany of complaints, and a plan is not to lay out programs that you can’t pay for.

He just said he wants everybody to be able to buy in to the same plan that senators and congressmen get. That costs the government $7,700 per family. If every family in America signed up, like the senator suggested, if would cost us $5 trillion over 10 years. It’s an empty promise. It’s called bait and switch.

He smiled when he said “bait and switch,” and then broke into a big grin when, in response to a time prompt from moderator, he added:

Thank you. [9.19]

The impression that George W. Bush had made in the first debate lingered all the way through the third. A Gallup poll taken immediately after the end of the rubber match gave John Kerry another victory by 52% to Bush’s 39%. [9.20]

In the next morning’s edition of The New York Times, an analysis of all the televised debates succinctly captured and reinforced the impressions each debater made.

In a crucible where voters measure the self-confidence, authority, and steadiness of the candidates, Mr. Kerry delivered a consistent set of assertive, collected performances. Mr. Bush appeared in three guises: impatient, even rattled at times during the first debate, angry and aggressive in the second, [and] sunny and optimistic last night. [9.21]

The audience perception of their widely different behaviors is clearly visible in the public opinion polls. From the very earliest moments of the 2004 campaign, armies of research organizations took the temperature of the electorate almost every day in every imaginable way. Despite slight differences in the results from the diverse organizations in one direction or another, the consensus was a dead heat. For most of that summer, each man’s percentage hovered around the high 40s, unable to break into a clear majority lead. The standard polling error of plus or minus three points was rarely exceeded, in effect, confirming that the race was too close to call. Most telling were the results in Figure 9.8, redrawn from the final Gallup poll before Election Day. (Note: The results for Ralph Nader, the third-party candidate, were insignificant and therefore omitted for clarity.)

Figure 9.8. Gallup Poll [9.22]

From early May 2004, all the way through the summer, and right up to Labor Day, Bush and Kerry ran neck and neck in nearly parallel trend lines that crisscrossed like a tight pigtail. The Democratic National Convention (DNC), which took place from July 26 to the 29, in John Kerry’s hometown, Boston, finally nudged Kerry just above 50%, but it was one of the smallest “bounces” any candidate ever got from so much media exposure. One political cartoonist lampooned Kerry’s poor performance with a sketch showing a man looking at Kerry’s poll results with a magnifying glass.

On the other hand, the media exposure of the Republican National Convention (RNC) in New York from August 30 to September 2 gave George W. Bush a big bounce. He surged to 54% over Kerry’s 40%, a lead he held until that eventful first debate on October 3. His poor performance in that contest dropped him right back into a virtual tie with Kerry. The trend lines converged again…and then stayed very close throughout the next two debates, right up to Election Day, November 2.

In the end, however, George W. Bush won by more than 3.5 million votes. The major factor in his victory goes back to Chapter 7: his loud, clear and consistent Topspin all throughout the campaign. The president was relentless in his focus on several key messages to his key constituents, while the senator all too often shifted focus and sometimes even contradicted himself. The evidence of their differential is best seen in the election results on the national map: the blue states that went for Kerry were at the periphery of the country on the coasts and along the top, but the solid block of red states in the center…the majority…went for Bush. It was the mainstream in the heartland, responding to George W. Bush’s repeated appeal to and promise of moral responsibility that awarded him his second term.

The Critical Impact of Debates

George W. Bush also succeeded in duplicating a feat that only his father, George H. Bush had accomplished…winning the election despite losing the debates. In the entire history of presidential campaigns, all the candidates (except the Bushes) who succeeded in their televised debates won their elections:

• 1960: John F. Kennedy defeated Richard Nixon in the election after he bested him in the seminal debate that set the pattern for all other debates to follow.

• 1976: Jimmy Carter defeated President Gerald Ford after the incumbent self-destructed in the second of their three debates during the Cold War when he said, “There is no Soviet domination of Eastern Europe and there never will be under a Ford administration.”

• 1980: Ronald Reagan defeated Jimmy Carter after their single debate when he notably responded to Carter’s position on Medicare by remarking, “There you go again!” Then, even more notably when, in his closing statement, Reagan looked into the camera and asked the nation, “Are you better off than you were four years ago?,” one of the most subtle and yet powerful, and subsequently often-copied political Topspins.

• 1984: Ronald Reagan defeated Walter Mondale in a landslide after essentially breaking even in their two debates, but skewering Mondale in the second debate with his classic Topspin, “I will not make age an issue of this campaign. I am not going to exploit for political purposes my opponent’s youth and inexperience.”

• 1988: George H. Bush defeated Michael Dukakis in the election after losing to him in their two debates.

• 1992: Bill Clinton defeated George H. Bush and Ross Perot with his famous charisma and George H. Bush’s infamous wristwatch blunder in the second of their three debates.

• 1996: Bill Clinton defeated Bob Dole with uncontested charisma not only in their two debates, but throughout the campaign.

• 2000: George W. Bush defeated Al Gore after their three debates in which he surpassed lower expectations while Gore overshot and undershot his higher expectations.

• 2004: Echoing his father’s accomplishment 16 years earlier, George W. Bush defeated John F. Kerry in the election despite losing in all three of their debates. [9.23, 9.24]

Lessons Learned

The lesson here is that George W. Bush’s poor performance in the first debate made a tight race out of what might have been a clear coast to victory. But the incumbent had other factors in his favor: an opponent whose frequent lapses into obscurity stood in sharp contrast to his own diligent trumpeting of his clarion call to arms, his Topspin.

The lesson for you: When you step into the line of fire, rely less on your competitor’s or challenger’s weakness and more on your own strengths. Take charge. Use Topspin and the many other techniques you’ve learned in this book to control your own destiny. In the next chapter, we’ll culminate all the techniques with a positive role model from a most unlikely source, but an expert in the art of war, a military general.