How to Lead During a Crisis: Lessons From the Rescue of the Chilean Miners

When 33 Chilean miners were rescued after being trapped underground for 69 days, the world cheered. Here’s what your company can learn from key leadership decisions made during the mine cave-in crisis.

The smart phone of Chile’s minister of mining, Laurence Golborne, came to life at 11 p.m. on Aug. 5, 2010, with a text message made even more chilling by its brevity and lack of detail: “Mine cave-in Copiapó; 33 victims.” Sixty-nine days later, standing by the mine, Golborne — along with an estimated 1 billion television viewers — watched as the cave-in victims emerged unscathed. A rescue crew had worked literally around the clock for more than two months to retrieve the 33 miners below, but direct responsibility for their recovery ultimately resided in just one individual — Golborne. The decisions he and his hand-picked team made during the length of the crisis contain instructive implications for all who face catastrophic risks or disasters.

Leadership Decisions in Crisis

Those who study catastrophic events — whether earthquakes, financial storms or mine collapses — often divide attention among three phases of the calamity, each calling for distinct forms of preparation or response: (1) the conditions leading up to a catastrophic event, (2) the immediate crisis brought on by the disaster, and (3) the recovery from it. For example, in the case of the BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico caused by an oil rig explosion in April 2010, attention was separately directed at the conditions that led to the blowout, the decisions of those responsible in the immediate aftermath of the explosion and the steps the company later followed to prevent recurrence.1

Research indicates that the influence of organizational leadership is greatest when an enterprise is facing uncertain and changing circumstances, and those conditions are arguably most acutely felt during the immediate crisis in the wake of a disaster.2 Leadership decisions during the second phase can be particularly fateful for the welfare of others and even survival of the enterprise itself.

But those decisions are also notably challenging because catastrophic risks are by definition high-impact but low-probability events. It is unlikely that those called to take responsibility for resolving a crisis have faced such decisions before. In the wake of the 9.0 earthquake and tsunami in Japan on March 11, 2011, for instance, government and company officials faced unprecedented decisions when nuclear materials overheated at several reactors.

Close study of leadership decisions made during a crisis promises to offer fresh insight into how individuals handle major challenges not previously experienced. In an era of unprecedented disasters ranging from terrorist attacks and financial crises to oil spills and nuclear threats, developing leadership increasingly depends upon being ready for the unthinkable.

About the Research

We have drawn on the extensive media coverage of the rescue and personal interviews with members of the rescue’s top team: René Aguilar, head of safety, El Teniente mine, Codelco, and deputy chief on rescue site, conducted Dec. 22, 2010; Cristián Barra, cabinet chief, Ministry of the Interior, Republic of Chile, Jan. 5, 2010; Laurence Golborne, minister of mining, Republic of Chile, Nov. 1, 2010, and June 22, 2011; Luz Granier, chief of staff to minister of mining, Nov. 1, 2010; and André Sougarret, manager, El Teniente mine, Codelco, and chief engineer on rescue site, Jan. 5, 2010.

Making Private Leadership Decisions Public

We define leadership decisions as those moments when an individual with organizational responsibility faces a discrete, tangible and realistic opportunity to commit resources to one course or another on behalf of the enterprise’s objectives. Making quality decisions has been well recognized by academic investigators as one defining aspect of leadership. Researcher Gary Yukl, for instance, has identified it as one of several core capacities required of all leaders.3

Yet detailed study of leaders in the act of making decisions has often proven unusually challenging. Organizational leaders communicate in public but decide in private. As a consequence, in the words of one inside observer, “most executive decisions produce no direct evidence of themselves.”4 The executive decisions of Laurence Golborne during the rescue of the 33 miners thus offers an unusual opportunity, since he and his top team members agreed in interviews to describe the decisions they made during the rescue. (See “About the Research.”) We supplemented those interviews by drawing both on the extensive media coverage (more than 1,400 journalists reported from the disaster site) and our prior study of leadership decisions.5

We focus on the person who led the rescue effort, Golborne. Two others also played critical roles: Chilean president Sebastian Piñera and crew foreman Luis Urzúa. Piñera insisted on searching for the miners at all costs, provided consistent support to Golborne and closely supervised the rescue efforts. Trapped with the miners, Urzúa helped form them into a microsociety to ration food, preserve morale and prepare for rescue. Though their decisions are also very instructive, they are beyond our space and scope here.6

Instead, our approach is to concentrate on the highest impact leadership decisions made by Golborne, where impact is defined as having influence on the course and outcome of the crisis moment. Given the scale and complexity of the miner crisis, we divide his leadership decisions into three stages: (1) taking overall responsibility for resolving the crisis, (2) creating and leading a team to solve specific issues in the crisis, and (3) choosing among the options for ending the crisis. Each stage required a distinctive blend of decision-making skills, and each decision had particular implications.

Taking Responsibility for Resolution of the Crisis

Within minutes of reading the disturbing text message that began this article, Golborne decided to travel to the disaster site. That travel decision triggered a chain of subsequent decisions that in time led to his taking full responsibility for resolving the crisis. Chile’s Ministry of Mining has regulatory power but not operating control over privately owned enterprises like the San Jose mine. But once Golborne arrived at the site, given that the miners’ lives and the country’s reputation were at stake, he found that he would likely be expected by many stakeholders to take responsibility for the rescue. It would have proven difficult for him to do otherwise. With “Mining” in his title and state resources at his disposal, he was arguably the person best positioned to affect a rescue. “Mining is my subject in the government,” Golborne explained. “Although I do not come from the mining world and was questioning myself what I could do in the mine — how I could help in the rescue given the magnitude of the problem — I understood I had to be there.”

Nonetheless, Golborne’s decision to travel to the mine and his inclination to take responsibility posed significant political risks, to both him and his government. His chief of staff, Luz Granier, a close advisor, initially challenged Golborne’s decision to rush to the mine. Her research showed no mining minister had ever visited the site of an ongoing crisis.

Golborne also understood that the mining disaster would become the government’s disaster if he took charge but failed to manage the crisis extremely well. “We were not part of the problem” at the start of the rescue, he recalled, but once he arrived at the mine, the government would become “the responsible party.”

There was another key reason for not going. As Golborne alluded above, in many ways he was not well prepared to lead the rescue. While he had majored in civil engineering at one of the nation’s premier universities, he was a businessman, who had studied management at Northwestern and Stanford universities after earning his engineering degree. Before joining the government he had been chief executive of Cencosud, Chile’s largest retail chain. When Golborne stepped down as CEO in 2009, Cencosud employed more than 100,000 people and reported revenue of more than $10 billion. Impressive to be sure, but running a company made up of department and home improvement stores as well as supermarkets is a far cry from heading a mining disaster. Golborne had been tapped just months before the cave-in to serve as mining minister by Chile’s newly elected president Sebastián Piñera, who was looking for someone with a proven management record to serve in his cabinet. “When I accepted the government’s invitation” to become the minister of mining, said Golborne, “I had a talk with my family and said, ‘this is where I can contribute with my management skills.’”

With the mining crisis now at hand, Golborne cautioned himself to keep in mind what he did not understand, and he delegated decisions that were well outside his field of expertise. At the same time, he was ready to apply his administrative and leadership skills. “I am not knowledgeable in mining,” he confessed. “I had visited two mines before this. I do not have technical knowledge.” But “what I do know is how to manage challenging projects, lead people, build teams and provide the necessary resources.”

When he arrived at the mine, Golborne joined a meeting with top representatives of the mine’s owner, the rescue team, the local police and the national government. The discussion was marked by confusion, including uncertainty over such fundamental facts as the number of miners trapped (the counts ranged from 34 to 37). Golborne decided to take control of the meeting, and in doing so, he moved another step along the path to accepting ultimate responsibility for the entire rescue.

Initial hopes of reaching the stranded miners were dashed at 3 p.m. on Aug. 7, the day of Golborne’s arrival, when a rescue crew found that a fresh cave-in had blocked any direct access to the miners. The rescuers also reported that signs of more instability made it unsafe for rescuers to reenter the mine at all. “They must be dead,” one of the crew members told Golborne privately, and “if they are not dead, they will die.”

Though in a state of shock, Golborne immediately decided to fully inform the miners’ relatives of the problems the rescuers were facing. Holding a megaphone, “I started telling them the bad news, but then I saw in front of me, two of the daughters of Franklin Lobos, the ex-footballer, who was in the mine. They had started to silently cry. I broke down. I could not continue speaking. But one of the relatives shouted, ‘Minister, you cannot break down. You have to give us strength!’” This moment, Golborne recalled, became “a turning point,” and he resolved to take full charge of the effort through its final outcome, whatever that might be.

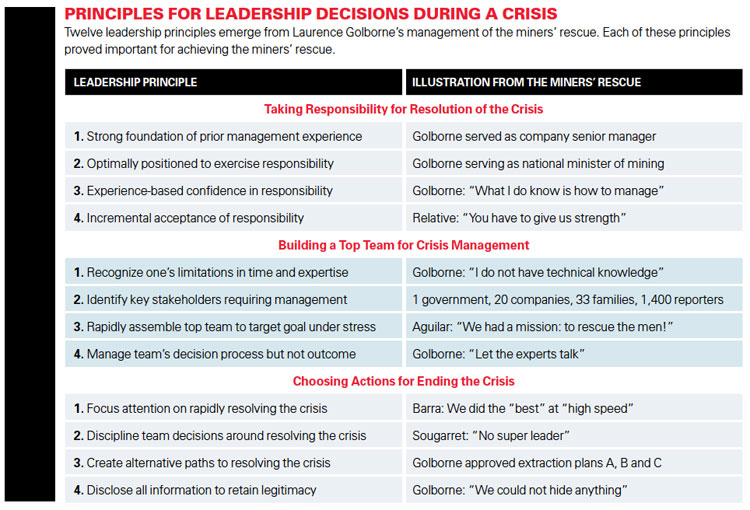

Principles for Leadership Decisions During a Crisis

Golborne’s decisions up until this moment suggest several implications for managers facing a crisis. First, a willingness to take responsibility depends on a strong foundation of prior management experience. Second, it is contingent on whether one is well or even optimally positioned by virtue of organizational location to exercise that responsibility. And third, it depends upon an experience-based confidence that one has the ability to orchestrate the work that will be essential for resolving the crisis — even if the leader is not steeped in the technical issues or functional areas that must be overseen.

Described differently, a willingness to take charge can be important for leading through a crisis. Emergency responders have long followed a protocol of assigning one individual to serve as “incident commander.” Though emergency responders have an established procedure for identifying who will serve as incident commander, crises like the one under discussion here usually do not, and the situation may remain rudderless until an individual is willing and able to step into the leadership vacuum. Despite neither technical knowledge about mining nor prior experience with a rescue, Golborne decided that organizationally he was best positioned to resolve the crisis and also that he possessed the management experience to oversee the major decisions even in areas where his expertise was limited.

Judging from Golborne’s personal experience, however, a fourth implication emerges as well. The act of taking charge in a crisis with no predesignated leader is not likely to be a quantum leap, as it is in the incident-command tradition. It instead may be more the culmination of a series of incremental steps, each experience moving the individual closer to accepting full responsibility. And among the more salient steps is a decision to engage directly with those most personally affected by the crisis.7

Building a Top Team for Crisis Leadership

Having committed to taking full charge of the rescue on behalf of the national government, Golborne now faced the challenge of executing a rapid retrieval, given the trapped miners’ limited time for survival. Knowing nothing of their medical condition or subsistence resources, or even if all had survived, Golborne decided that he would have to immediately build a crisis team that could create and execute a plan for swiftly reaching the miners trapped more than 2,000 feet below the surface without access to pre-existing shafts or tunnels.

The immediate impetus for forming the top management team emerged from an early discussion of how to reach the miners. After learning of a proposal to drill 5-inch boreholes to try to locate the miners and then winch down supplies, Golborne decided that that should be the immediate next step, but he also concluded that he needed a mining expert to take charge of the effort. “I realized that in the technical issues we did not have the needed leadership. Although I am an engineer,” he confessed, “I do not have any technical knowledge about mining.”

Making the need for an expert as part of the team even more pressing were the other engineering solutions being offered by a host of parties flooding onto the site, with some 20 companies soon volunteering their equipment, personnel and expertise. “There were too many voices,” Golborne said, and nobody at the site seemed to have the expertise to choose wisely among them. He decided that a senior manager from Codelco, the powerful state-owned copper mining company, would bring the necessary experience and authority onto his top team. Codelco assigned the drilling oversight to senior engineer André Sougarret, and when he arrived at the San Jose mine, Golborne was direct with Sougarret about the engineering tasks ahead: “You have to take charge!”

It was not, however, as if Golborne abandoned the technical discussions about what would be the best way to quickly and safely reach and extract the miners. He believed that he must move cautiously for fear of forcing the wrong technical decisions — but also for fear of attracting public blame to his government if the rescue failed. Golborne warned himself that if he became too deeply involved in the early technical decisions, outsiders could later ask, “What do you know?” And then, if the next steps failed or put rescuers at risk, he feared that some would question his decisions: “Why did you get in the middle if you knew nothing?”

Drawing on his business experience, Golborne thus sought to shape the dialogue so that his top team members could largely decide on the engineering issues on their own. “As a minister,” he said, “I did what I normally do,” that is, to “let the experts talk.” He would work to ensure — by probing and asking questions — that the engineers had sound technical rationale for each of the major steps they would be taking, and he also opted to serve as the final arbiter of all otherwise unresolved issues.

A Different Set of Management Challenges

The miners’ families presented a separate set of management challenges. The sister of one of the trapped miners, who had emerged as the relatives’ spokesperson, declared, “We’re not going to abandon this camp until we go out with the last miner left.” As Golborne recalled, “the pressure from the relatives was tough. They were very upset” and “they did not believe what we were telling them.”

Codelco had also sent the safety director of one of its mines, psychologist René Aguilar, and Golborne assigned him responsibility for working with the miners’ relatives and managing the many subcontractors. To Cristián Barra, cabinet chief for the Ministry of the Interior, Golborne gave the task of managing the rescue team’s relations with the national government. Implicitly drawing on Jim Collins’s leadership prescription in his book Good to Great to get the “right people” on the “bus” and the wrong off, Golborne also removed the mine’s chief executive from any role in the top team.8

The top team members found themselves performing under the spotlight and stress of the moment, as René Aguilar recalled in working with the miners’ families: “There was a lot of sorrow with the relatives. I had to manage myself. I felt anguish every night as we did not know whether the men were alive. Every night, when leaving the mine, I had to walk through the camp, I would see the banners saying: ‘Daddy, we are waiting for you.’ ‘Son, we are here.’”

Keeping an eye on the ultimate objective helped Golborne’s inner circle retain its equanimity despite profound anxieties about the outcome. “If you are not conscious of why you have to stand the pressure, it is difficult,” said Aguilar. “We had a mission: to rescue the men!” With that defining objective repeatedly reinforced by their daily personal contact with the miners’ relatives, Golborne and his top team found it easier to find alignment and avoid distractions.

Open collaboration defined the team’s decision-making process. “There was no super leader who had all the answers,” recalled André Sougarret. “I liked the honesty with which we were working. … I could feel we were playing with our cards open on the table.” Much of the credit for that transparency and urgency goes to the senior team members who willingly embraced them, but much of it also derived from the mind-set created by their team leader.

Drawing on Golborne’s team experience, several implications for exercising leadership during a crisis become evident. First, a readiness to recognize the specific limitations of one’s own time and expertise provides a platform for building out a top management team. Second, identifying all the critical stakeholders — in this case miners, drillers, relatives, subcontractors and government — points to the kinds of individuals who should be included on the team. Third, rapid assemblage of the top team and disciplining it to work under stress is essential. And fourth, given the need for both general and technical management, the self-defined role of the crisis manager is to lead the team’s decision process but not micromanage its technical considerations.9

Choosing Actions for Ending the Crisis

In the aftermath of his decisions to take charge and to create the top team, Golborne turned his attention to the final goal of locating and then extracting the lost miners. Here he adopted a practice of redundancy, pursuing two or more simultaneous strategies so that if one faltered or failed, time would not have been lost in developing the other options. This is a practice found in other fast-moving management environments.10

For locating the miners, Golborne created two drilling teams. One would seek to drill a hole down to a ventilation shaft not too far above the miners’ location. The second would work to drill an opening all the way to where the miners were trapped. Even by pursuing the two-pronged strategy, Golborne believed that the likelihood of either succeeding was not large. In the case of the second strategy, for instance, the team would be drilling a 5-inch shaft down more than 2,000 feet, and just a degree or two of deviation from perfect alignment could easily cause the shaft to miss the small cavity that rescuers believed contained the miners. Still, he concluded these two plans were the best options.

With both gains and setbacks anticipated, Golborne embraced a policy of fully disclosing not only the drillings’ successes but also their failures. On the premise that openness must be complete and consistent for his own leadership to be credible with the key stakeholders, every time a drilling problem emerged, Golborne made a point of candidly informing the relatives and the media. “The decision of transparency was a conscious decision made early on. There were too many people, we could not hide anything,” he explained. “If we did, we would lose their confidence.”

At 6 a.m. on Aug. 22, when a drill reached a depth of 2,191 feet, rescue workers heard faint tapping on the drill. When the drill head was retracted to the surface, it carried a message scrawled in red letters: “Estamos bien en el refugio, los 33” — “We are fine in the shelter, the 33.”

Reading that message proved stunning, a defining moment for many on the rescue team. René Aguilar recalled, “It was the happiest day in my life. More than happy, total jubilation!” For Golborne, the rescue’s mastermind, “I call that day the epiphany.” It “was a magical moment,” something “extraordinary, fantastic.”

Soon after the breakthrough, the rescuers lowered a video camera down the narrow borehole, and the live images, broadcast around the world, revealed a group of miners in far better condition than most had feared. Amidst the elation on the surface, Golborne’s attention immediately shifted to the challenge of extracting the miners. Not surprisingly, a range of options — 10, to be exact — were already in various stages of development. Three schemes emerged as favorites, each with a different approach and equipment.

Plan A would entail drilling a new shaft with a 31-ton drill; Plan B involved widening the initial 5-inch boreholes to 27 inches with the same equipment already in use, making it the lowest-cost option; and Plan C involved bringing in a petroleum drilling rig that required a large area to operate, the fastest but also the most costly of the three. Though Golborne was not familiar with the plans’ technologies, he delved into the technical merits of each proposal. Again hedging his bets, Golborne approved simultaneous implementation of all three plans.

On Oct. 9, after 33 days of drilling under Plan B, Golborne announced just after 8 a.m. that its newly created rescue shaft had reached the miners. At that moment, Plan A’s drilling had reached a depth of 1,960 feet, and Plan C just 1,220 feet. Three days later, Golborne and his team commenced extraction of the miners via the Plan B shaft in a specially designed capsule.

At 8:55 p.m. on Oct. 13, the last of the miners, Luis Urzúa, the shift foreman, reached the surface, declaring, “I’ve delivered to you this shift of workers, as we agreed I would.” A group of rescuers still in the refuge after the last miner had ascended displayed a sign, “Misión cumplida Chile,” or “Mission accomplished Chile.”

In reflecting on the team that had directed the rescue, Interior Ministry official Cristián Barra offered, “We met, the four of us. Each one said what he would do.” And in the weeks ahead, he, René Aguilar, Laurence Golborne and André Sougarret followed their script. None sought the spotlight more than others, Barra recalled, and each executed his responsibilities in collaboration with the others. They had to do “the best and at high speed,” he concluded.

Drawing on Golborne’s choice of actions to end the crisis, several final implications for crisis leadership become evident. First, an unequivocal focus on the objective of resolving the crisis serves to energize and motivate the team. Second, disciplining the team’s decisions around achieving that goal can be vital when there is little room for error. Third, given the press of time and uncertainties of outcome, creating multiple alternative paths for resolution of the crisis optimizes the likelihood that one will ultimately succeed. And fourth, the full and timely disclosure of all vital information serves to help ensure that the crisis leader retains legitimacy in the minds of all stakeholders.

In Golborne’s experience, we witness a set of actions that point toward a set of leadership principles for leading during a crisis. Drawing on the concept of the “checklist manifesto” developed by the surgeon and writer Atul Gawande, we summarize the 12 leadership principles that emerge from Golborne’s management of the miners’ rescue. (See “Principles for Leadership Decisions During a Crisis.”) As in the case of an aircraft pilot’s checklist, each of the principles proved important for achieving the miners’ rescue, and we believe that most or all were required together to produce the outcome.11

Close study of other leaders during a crisis is likely to yield crisis leaders’ checklists with modestly different blends of principles, but we expect that many or most of the principles seen here are likely to be viewed as important in a range of other settings. If so, from witnessing Laurence Golborne’s experience in successfully leading the rescue of the 33 miners trapped below, we have acquired an experience-tested set of leadership principles for crisis management.

Michael Useem is professor of management and director of the Center for Leadership and Change at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Rodrigo Jordán is adjunct professor of leadership and innovation and Matko Koljatic is professor of strategic management at the School of Business Administration at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile in Santiago.

References

1. H. Kunreuther and M. Useem, “Learning from Catastrophes” (Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2010); BP, “Deepwater Horizon Accident Investigation Report,” Sept. 8, 2010; and National Commission on the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill and Offshore Drilling, “Deep Water: The Gulf Oil Disaster and the Future of Offshore Drilling” (Washington, D.C.: GPO, 2010).

2. D.A. Waldman, G.G. Ramírez, R.J. House and P. Puranan, “Does Leadership Matter?: CEO Leadership Attributes and Profitability Under Conditions of Perceived Environmental Uncertainty,” Academy of Management Journal 44, no. 1 (February 2001): 134-143.

3. G. Yukl, “Managerial Leadership: A Review of Theory and Research,” Journal of Management 15, no. 2 (1989): 251-289.

4. C.I. Barnard, “The Functions of the Executive” (1938; repr., Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1968), 193.

5. R. Jordan and M. Garay, “Liderazgo real: De los fundamentos a la práctica” [Real Leadership: From Theory to Practice] (Santiago, Chile: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2009); and M. Useem, J. Cook and L. Sutton, “Developing Leaders for Decision Making Under Stress: Wildland Firefighters in the South Canyon Fire and Its Aftermath,” Academy of Management Learning and Education 4, no. 4 (December 2005): 461-485.

6. J. Franklin, “33 Men: Inside the Miraculous Survival and Dramatic Rescue of the Chilean Miners” (New York: Putnam, 2011); and M. Pino Toro, “Buried Alive: The True Story of the Chilean Mining Disaster and the Extraordinary Rescue at Camp Hope” (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011).

7. L.A. Hill and K.L. Lineback, “Being the Boss: The 3 Imperatives for Becoming a Great Leader” (Boston: Harvard Business Press, 2011).

8. J. Collins, “Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap ... and Others Don’t” (New York: HarperBusiness, 2001).

9. T.J. Neff and J. M. Citrin, “You’re in Charge — Now What?: The 8 Point Plan” (New York: Crown Business, 2007).

10. K.M. Eisenhardt, “Speed and Strategic Choice: How Managers Accelerate Decision Making,” California Management Review 32, no. 3 (1990): 39-54.

11. A. Gawande, “The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right” (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2009).

Reprint 53106.

For ordering information, visit our FAQ page. Copyright © Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2011. All rights reserved.