42 5. EVALUATING INTERACTIVE IR USER STUDIES OF DIFFERENT TYPES

According to the rst premise, the values of the major facets should be determined according

to the specic research focus and problem(s). e second premise suggests that dierent facets or

dimensions cannot be evaluated in a separate, individual manner. Instead, we should focus on how

dierent facet values interact and “collaborate” in facilitate the investigation of research problems.

e existing works on IR study evaluation mainly focus on data analysis and the statistical result re-

porting practice (e.g., Sakai, 2016) or report a small set of user study components separately without

fully revealing the possible connections among them (e.g., Kelly and Sugimoto, 2013). To address

this issue and to emphasize the role of the connections among dierent facets of user studies, we

employ our faceted framework in evaluating dierent combinations of facet values that represent

dierent decisions and even compromises made in varying problem spaces.

In the following sections, we explain the idea of faceted evaluation in the three types of user

studies respectively (i.e., understanding user behavior and experience, IIR system/interface features

evaluation, meta-evaluation of evaluation metrics). To fully illustrate the connections among facets

and evaluate divergent study design decisions, we apply the faceted framework in evaluating a set

of representative user studies reported in recently published research papers. Given the comprehen-

siveness of our faceted framework, it is safe to say that our approach can be applied in evaluating a

wide range of IIR user studies.

5.1 UNDERSTANDING USER BEHAVIOR AND EXPERIENCE

In faceted evaluation, we rst selected and focused on a series of major facets based on the research

focus and questions, aiming to accurately identify and represent the major decisions and compro-

mises made in study design. Specically, for each examined user study under the corresponding

category (here it is understanding user behavior and experience), we reviewed the values of the sub-

facets (i.e., independent variable, quasi-independent variable, dependent variable) under the facet,

variable, and assessed the implicit connections between them and the values of other relevant facets

and subfacets in our framework. Our core argument behind this approach is that the decision on

and evaluation of one facet value should take into consideration other relevant facet values and their

impacts on the procedure and results of the study.

For instance, in Edwards and Kelly (2017), researchers used both task and SERP quality to

manipulate participants’ emotional states in web search in a within-subjects design study. In this

case, our major facets and subfacets of interest in evaluation include: search task and topic, system

interface elements varied (SERP quality), search behavior and experience. Given the goal of this

research (inferring emotion from behavior in search tasks), researchers assigned evaluate tasks in

the study as these tasks are engaging and complex enough to elicit multi-round, rich interactions

between users and systems in laboratory settings. e task topics were varied so that researchers can

better control the eects of specic topics and observe relatively “clean” task eects. Liu et al. (2019)

43

employed similar strategy (designing dierent topics for the same task types) in order to separate

the behavioral impacts caused by topics and tasks.

Beside the values in individual main facets that are directly associated with the predened

research problem, in the faceted evaluation we also considered the facets and subfacets which were

directly related to the balance between the major facets. Specically, in Edwards and Kelly (2017),

we found that the method of statistical modeling (i.e., hierarchical linear model) should be taken

into account for user study evaluation as it controls the random eects caused by task time, which

can be of help in at least partially controlling the potential negative eect of not controlling search

task completion time (the researchers did not set a time limit for completing the tasks). Under

this circumstance, researchers did a good job in reaching a balance among interrelated facet val-

ues: elicit relatively natural search behavior from the task context with no arbitrary time limit (to

meet the major research goal) and also control the variation caused by this design choice at the

statistical level.

It is worth noting that interventions on system and/or interface components have been used

in both search behavior exploration and IIR evaluation research (e.g., Kelly and Azzopardi, 2015;

Klouche et al., 2015; Ruotsalo et al., 2018; Shah, Pickens, and Golovchinsky, 2010; Turpin, Kelly,

and Arguello, 2016; Umemoto, Yamamoto, and Tanaka, 2016). e major dierence is that in

search behavior research involving human experience or cognition, system and interface features are

usually designed or implemented as tools to manipulate user-side variables at dierent levels (e.g.,

behavior, cognition, experience and engagement), whereas in IIR evaluation studies, system and

interface features themselves are treated as the research focuses and are evaluated from the user’s

perspective. erefore, in user behavior and experience studies, it is critical to evaluate the eective-

ness of the system-based human factor manipulation that serve as the cornerstone for other compo-

nents of user studies. In Edwards and Kelly’s (2017) case, the eectiveness of SERP-quality-based

manipulation of user frustration was veried by a set of survey-based standard ground truth mea-

sures. Hence, the quality of user feature manipulation and search perception measurements as two

separate facets are closely related in this case. Similarly, in another example, Ong et al. (2017) used

SERPs of varying qualities to manipulate information scent level (as a part of information foraging

context) and veried the eectiveness of this manipulation via external assessors’ annotations. ese

designs and reporting practices can facilitate the explanation of researchers’ decisions in “facet engi-

neering” and can help readers and reviewers evaluate the validity of the designed interventions and

manipulations as well as the reliability of the conclusions drawn from the user study.

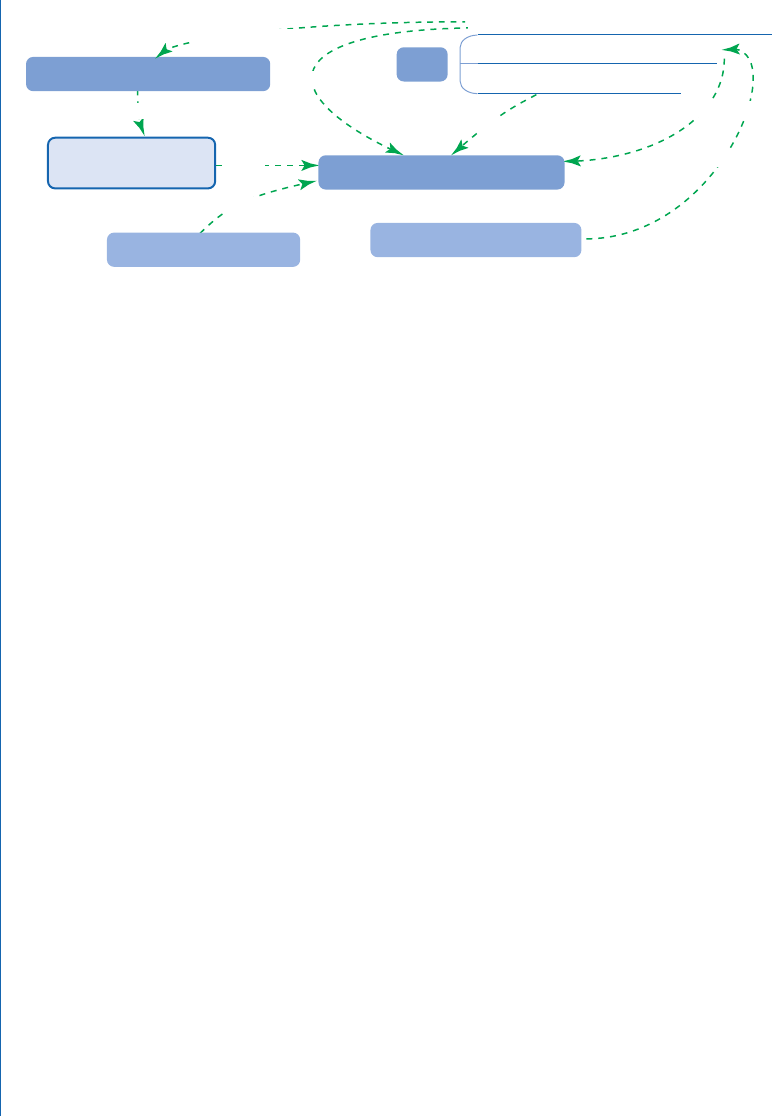

As an illustration and application, we employed our faceted framework in evaluating the user

study reported in Edwards and Kelly (2017) (see the facet map in Figure 5.1).

5.1 UNDERSTANDING USER BEHAVIOR AND EXPERIENCE

44 5. EVALUATING INTERACTIVE IR USER STUDIES OF DIFFERENT TYPES

Topic (select tasks based on users’ ranking)

Task Time: no arbitrary time limit

Control: task type (evaluate)

Task Interest and SERP Quality

Emotional State

Task

Search Behavior and Experience

Hierarchical Linear Model

Within-Subjects Design

elicit natural search behavioral ta

sk variation

obtain rich interactionl learning eect and user fatigue

manipulate

topic variation

control: random eects

obtain rich interaction

manipulate task interest

aect

⊝

Figure 5.1: Faceted evaluation example: a facet map.

Despite the uniqueness of every specic user study, the faceted framework consisting of gen-

eralizable facets and subfacets can still be applied in deconstructing, characterizing, and evaluating a

wide spectrum of IIR research. With this unied faceted framework, researchers can better extract,

summarize, and manage the metadata of user studies.

In general, when evaluating a user study using the faceted framework, one can start with the

core facets (e.g., independent and dependent variables, task features) identied according to the

research focus as they should be the top priority for the study. en, the researchers can gradually

expand the evaluation analysis by incorporating other relevant facets (e.g., recruitment, participants’

motivations and knowledge background, statistical analysis) which are manipulated to keep the

balance among facets, provide additional supports for answering the questions, and compensate for

the limitations of the study design compromises made in other dimensions.

During this process, the researcher should consider and evaluate: (1) the quality and use-

fulness of each individual facet value in the entire study (e.g., the quality of task, the usefulness of

system component(s) in manipulating users’ perceptions); and (2) the role and structure of the con-

nections among dierent facet values. For instance, in the case presented in Figure 5.1, we started

with the research questions and associated variables (emotional states as independent variables,

search behavior and experience as dependent variables) and identied the core balance here: making

decisions and compromises in some of the task aspects to ensure the successful manipulation of

emotional state (which is the top priority and main focus of the user study). On the dependent

variable side, a variety of design decisions were also made for the purpose of obtaining rich search

interaction data (e.g., within-subjects design, no time limit for search session, restrict task type to

evaluate task only). en, with respect to the multi-facet connections and collaborations, we took

into account the techniques and the associated facets involved in controlling the damages or lim-

itations caused by the aforementioned design decisions (e.g., statistical methods, randomize topic

order).

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.