6

The Quantified Self and Mobile Health Applications: From Information and Communication Sciences to Social Innovation by Design

6.1. Introduction

Connected objects and portable screens are being integrated into our everyday lives little by little. They are becoming smaller, increasingly ergonomic and less and less perceptible when worn on the human body. They can collect physiological, behavioral and geo-localized data. As a result, a culture of a body that is more equipped with technological objects that make it possible to collect, store and visualize personal information about the self is developing. To that extent, we have entered into “the culture of the Quantified Self” [LAM 14], based on the self-measurement of personal parameters and interconnection between portable screens, connected objects and social networks. Numerous objects with increasingly elaborate devices accompany athletes or simple citizens who want to gather data on themselves. Chris Dancy is a striking example of this practice. This North American resident collects large quantities of data about himself day and night. Between 2010 and 2013 he lost a large amount of weight as a result of the impact of biofeedback, which allowed him to use information technologies linked to each other via the Internet of Things. His physical transformation was displayed on the multiple platforms that make up his digital identity in such a way that it constitutes a paradigmatic example of the possibility of modifying the body using the Quantified Self. His daily use of connected objects synthesizes both the promises and the concerns of connected health, home automation, and enhanced reality used for the purposes of prevention or even behavioral prediction. This unique experiment is interesting to analyze in order to grasp what the integration of information technologies into our daily lives entails. The analysis of Chris Dancy’s use of objects is aimed at answering the following questions: how do connected objects transform the relationship between the individual, his body and its representation, how do they move the human-machine relationship toward more online social interactions and lead to a form of spectacularizating communication of his own data? To understand the multiple issues that this problem raises, an interdisciplinary approach combining the analytic tools of semiotics, design and the anthropology of communication is proposed.

The qualitative analysis involves a corpus made up of data collected from the multiple platforms that make up Chris Dancy’s digital identity. Although our observation phase stretches over three months (February–May 2015), the data collected falls within a longer period of time (2010–2015) in order to analyze Chris Dancy’s physical transformation. The corpus is made up of different types of supports: photos and texts published on socio-digital networks (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter), visual data from two applications used by Chris Dancy (FitBit and Existence), the discourse on his relation to connected objects published on his two web sites (www.servicesphere.com and www.chrisdancy.com) as well as in interviews (in particular those done for the magazine Mashable) and slideshows of his conferences about his information technology experiments on his Slideshare channel. Within the framework of this study, it was necessary to make choices about the large corpus of data collected. The selection was made using criteria salient to the problem by choosing in particular the data that demonstrates the factitive dimension of the objects used by Chris Dancy and the specific relationship that he was with them.

With regard to the methodology, the analysis of the corpus is done in three levels. The first concerns the study of the staging of his physical transformation on socio-digital networks and the social interactions that generate this staging. The second deals with the aesthetic dimension of the representation of data on “health” applications from a semiotic perspective, to characterize the information design of applications, the factitive dimension of connected objects used by Chris Dancy, as well as the value system at the heart of interfaces. This analysis is completed by an intermedial approach that puts information design and data visualization into historical perspective. Finally, there is a look at Chris Dancy’s vision of interaction design aimed at understanding how this paradigmatic example crystallizes a particular relationship to information technologies and is part of a trajectory of technologies that should be interrogated critically.

The study is broken down into four parts. First, it involves revisiting the definition of certain terms related to the Quantified Self and m-health in order to characterize the information technologies used by Chris Dancy. The second part presents the results of the selective analysis, emphasizing Chris Dancy’s transformation. The third part concerns the factitive dimension of the devices used by Chris Dancy, in particular the value system at the heart of his relationship with his portable technologies and his vision of interaction design. From an anthropological perspective, it also involves placing this phenomenon within the conception of information technologies and embedded computing. The fourth part provides a critical perspective built around this particular case. It opens up to a more global reflection on the bioethical, institutional and socio-economic challenges raised by connected objects used in the healthcare sector. It also looks at how the development of connected objects and ubimedicine transforms the triadic relationship between patients, doctors and public and private health institutions. Finally, the article proposes other paths to consider [GRA 13] for m-health technologies based on the anthropology of communication and social innovation by design.

6.2. The evolution of interfaces and connected objects toward anthropotechnics

6.2.1. From e-health to the “Quantified Self”

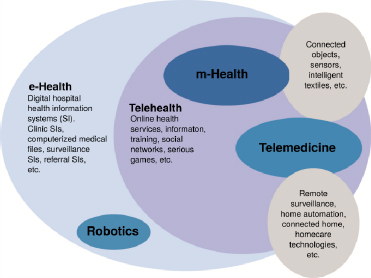

First of all, it seems necessary to define and distinguish between the terms often associated with the promotional discourse accompanying the development of self-measurement devices and mobile applications in the field of health and well-being. E-health, m-health and the Quantified Self are often used together, which contributes to the confusion for users, even though they cover very different data processing processes and practices, as depicted in Figure 6.1.

According to the European Commission, the term e-health (or e-Health) “refers to all of the technologies and services for medical care based on ICT” [COM 09]. It includes a variety of diverse practices, from telemedicine to information systems for healthcare professionals. The use of the term has been trivialized to the point where it just refers to “everything that contributes to the digital transformation of the healthcare system” [CON 15]. M-health (or m-Health) is an extension of e-health focused on mobility using portable information technologies and devices connected to a mobile network. It simultaneously includes medical practices and public health supported by mobile devices as well as monitoring and surveillance of patients via communicating measuring devices. Finally, the measurement of the self (or Quantified Self) “refers to a group of varied practices which all have the common characteristic of measuring and comparing variables relating to someone’s way of life” [CNI 14]. The development of the Quantified Self is related to the development of the Internet of Things. The Quantified Self movement has been growing at such a high rate since 2011 that it gives the impression of being innovative and unprecedented. However, self-measurement has been a common practice since the introduction of home scales and thermometers in the 19th Century. The novelty of the Quantified Self is not the act of measuring the self but rather that the data collected is being shared via the Internet of Things. Consequently there is a major difference between m-health and the Quantified Self in terms of the collection and access to data. Indeed, in m-health, it is the healthcare professionals who ask patients to collect the data, which remains between them and their patients. With the Quantified Self, it is the individual who takes the initiative to measure his or her personal data and communicate it to others, in particular via socio-digital networks.

Figure 6.1. Distinction between Telehealth, e-health, m-health and Telemedicine (Connected health. Livre blanc du Conseil national de l’ordre des médecins, 2015, p. 9)

At his point, we can ask ourselves if the daily use of multiple portable sensors also falls within the domain of health. For the OMS, health encompasses a “state of physical, mental and social well-being.” We can therefore decide that Chris Dancy’s use of information technologies, which cannot be reduced to the monitoring of his physiological data, falls outside the healthcare field. It seems more pertinent to consider his use of portable information technologies as relevant to “anthropotechnics” which are defined as: “the art or technique of extra-medical transformation of the human being through intervention on his own body” [GOF 06].

6.2.2. Anthropotechnics and the information ecosystem of Chris Dancy

The illustrations below make it possible to visualize the different devices worn: connected bracelet, armband and glasses, camera and portable camera, physiological sensors and connected portable screens that record his movements and geo-localize him.

Figure 6.2. The devices1 worn every day by Chris Dancy. Photograph published in Paris Match, July 2014. http://www.parismatch.com/Vivre/High-Tech/L-homme-le-plus-connecte-du-monde-577862

In addition to these portable devices, other technologies are integrated into Chris Dancy’s domestic space2 which refer back to the field of home automation. For example, to measure his sleep, he combines a sensor next to his bed with the bracelets that he wears on his wrist. He also uses heat and movement sensors in the room. The lights and music are programmable remotely for creating a particular mood, especially when he returns home after a business trip. In this way, Chris Dancy deploys an entire complex information and communication ecosystem made up of both the connected objects that he wears and the sensors integrated into his household furnishings. He performs the daily recording of his physiological and biometric data in order to analyze and visualize it on the three computer screens that he uses in his office. All of the devices are interconnected via Wi-Fi and the data circulates from one interface to another (in particular from smartphone screens to computer screens).

His office is a very distinctive space. Several types of object coexist: three flat screens and multiple sensors (a cube sensor for example) are mixed with books (in particular ones by Warhol) and decorative objects. His wall is covered with wood panels on which he has created a collage of press clippings, photos, phrases for meditation and multiple objects. There are also statues next to the digital devices. He uses two different seats: an ergonomic chair for working on these three screens, and a wooden chair decorated with feathers and multiple sculptures, which recalls those of the great Native American chiefs.

Figure 6.3. Chris Dancy in his office: cultural and technological hybridization. Photograph published on the website of the magazine Mashable in August 2014, http://mashable.com/2014/08/21/most-connected-man/#0TM6VmdLGkq1

Thus, this piece illustrates the fetishistic relationship that Chris Dancy maintains with his information technologies: it is a sort of datacenter from which he controls his data. This space makes up the cornerstone of his self-monitoring system and is characterized by a strong cultural and technological hybridization.

Another room attached to the office is reserved for recharging all of the devices that he uses every day. It is equipped with a USB hub with more than 30 ports to recharge the hundreds of connected objects that he uses.

6.2.3. Connected objects as the heirs of ubiquitous computing

Although the development of connected objects seems new, it’s necessary to place it within the history of information technologies. Chris Dancy’s connected objects are communicating objects, characterized by “their capacity to mutually recognize one another” (LCN, 2002). The development of communicating objects follows “a general trend of the spreading and burying of technologies” [DEM 02]. It is based on two major changes: “the digital convergence of information technologies and the common “mobilification” of these objects [PRI 02]. By melting into the domestic environment, communicating objects tend to disappear into the environment to create ambient communication, building a symbiotic relationship between Chris Dancy and his surroundings. This particular interaction has already been considered in works on “ubiquitous” computing and “the attentive environment” [WEI 91]. It leads to a transformation of the relationship between the user and the interfaces, since the multiple interconnected objects make up a diffuse interface, “submerged transparently in the environment” [PRI 02].

From a middle perspective, we can observe a competition and synergy between computer screens and smartphones around which Chris Dancy’s communicating objects gravitate. Connected objects give the smartphone a central role because designers of connected objects and mobile applications prefer its screen, which is adapted for mobility. There is also a complementarity between the telephone and computer screens, if you consider synchronization between these two screens, and the circulation of mobile media [CAT 12] from connected objects to the smartphone then to the computer. On the other hand, the portable screens that accompany Chris Dancy daily (such as his smartphones or his connected bracelets) behave like personal digital assistants that recall the PDAs that appeared at the end of the 1980s.

From a semiotic and socio-cultural point of view, Chris Dancy’s screens are simultaneously “action” and “contact” screens [LAN 10]. His portable screens also belong to the category of “intimate screens” [TRE 14], whose principle characteristics are mobility and experience. Chris Dancy himself divides his data into “little data” and “experiential data” highlighting the passage of Big Data to the individual scale. The paradox of these intimate screens lies in the fact that they are interconnected with the public sphere, via the network of the web: in this way, they mediate Chris Dancy’s personal data and share it well beyond his intimate sphere. All of this leads to questions about the role of screens and connected objects in his relationship to others and to his own body.

6.3. Factitive dimension and value system at the heart of Chris Dancy’s relationship with his information technology

We can consider Chris Dancy’s connected objects as “factitive objects” [DEN 05] and analyze the way in which they shape his behaviors and social interactions. By offering him recommendations based on the data collected, they have participated in the modification of his body and his social life. The factitive dimension of his connected objects rests in their capacity to provide biofeedback in real time, which leads him to modify his behavior. This quantification of his daily life is then transformed into individu-data [MER 13].

6.3.1. The progressive development of the figure of the enhanced human in socio-digital networks

Three photographs posted on Facebook play a part in the dramatization of Chris Dancy’s physical metamorphosis from 2010 to 2013. This display constitutes a spectacularization of his body, as part of a storytelling approach [SAL 08]. Beyond the transformation of Chris Dancy’s face, resulting from his weight loss, it is interesting to observe the evolution of the attributes of his persona. Starting in 2011, he wore glasses with very visible black contours. Then, in 2013, he acquired a Google Glass that he wears for all his media appearances, to the point that it has become central to his “enhanced” human persona.

The value of Chris Dancy’s metamorphosis as a result of his anthropotechnics appears in the comments of his “friends” on the 2013 photo: they describe him as “handsome” or even “looking great.” The change therefore involves his relationship to others and himself, with a self-improvement approach.

Figure 6.4. Dramatization of Chris Dancy’s metamorphosis on Facebook (profile photo)

6.3.2. Information design and data-visualization: the case of Fitbit and Existence

We can then analyze the mobile applications used by Chris Dancy by exploring both information design and data-visualization. This second level of analysis involves a double dimension: aesthetic and semiotic. In the application Fitbit, the data collected is visualized in the form of daily graphics: bar graphs for the step counter, line graphs for heart rate, donut charts to evaluate sleep quality. The application also measures the calories burned by the user. In the application Existence, the user can explore his or her timeline to analyze his or her daily activity via donut charts, and optimize his time, at the same time that he gets feedback on the same daily activity. The application appears to be designed with an “ethic of compassion” in the vein of contemplative computing3 [SOO 11].

These two interfaces are nomadic, since the data can be consulted on a smartphone and a computer via the Internet. They seem to represent two information design trends in the Quantified Self: the first is created from a design centered on performance, while the second claims to be contemplative design, meant to distinguish it from disruptive computing. In the two applications, we can see the recurring use of donut charts, which are the dominant representation in many applications based on data-visualization. If we place the information design of these applications into a historical perspective, we observe that graphics are just a re-actualization of the principles of graphic semiology [BER 67] adapted to contemporary visual culture. What is new, however, is that these are personal messages addressed to the user by the computer system to congratulate or encourage him. This significant detail is an important feature for users of these objects that have been transformed into a kind of life coach.

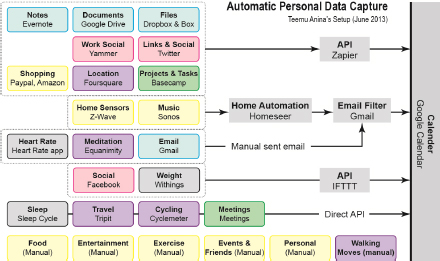

The data that Chris Dancy collects on himself is partly processed and visualized by health/well-being applications, as well as also through manual processing and data visualization with different software programs (in particular Evernote, Spreadsheets and Google Calendar). These systems are familiar to him because he was for more than twenty-five years in the information technology sector, working for businesses. The illustration below makes it possible to visualize the complexity of the information systems that he deploys.

Figure 6.5. “Diagram of the workflow” created by Teemu Arina for Chris Dancy’s blog. http://www.servicesphere.com/blog/2013/12/5/explaining-my-quantified-self-or-coming-out-of-my-data-close.html

We can observe that a part of the data collection is carried out automatically by the different software programs to which they are connected. Another part of the data, concerning food, entertainment, physical exercise and social life, is entered by Chris Dancy himself every day.

6.3.3. Animism and anthropomorphism: a particular relationship to connected objects

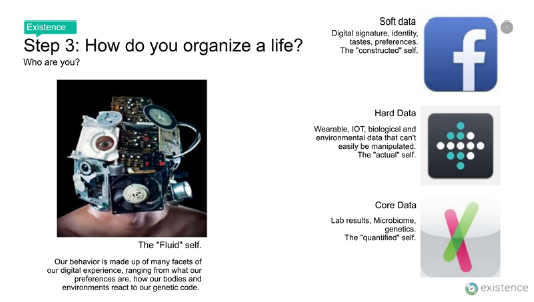

We can finally look at Chris Dancy’s discourse on the intimate relationship he maintains with his self-measurement information technologies. On his website and blog, he presents himself as “the most connected human in the world” and a “mindful cyborg”. His stated goal is to map his existence, with the help of the hundreds of sensors, devices, applications and services that he uses every day. The goal of his approach appears clearly in the slideshows that he shares on his Slideshare4 channel, especially in “Existence: the human information system.”

Figure 6.6. The concept of “fluid self.” Screen capture of a slideshow by Chris Dancy on Slideshare. http://fr.slideshare.net/chrisdancy/the-human-information-system-byod-wearable-computing-and-imperceptible-electronics

Chris Dancy distinguishes three types of data that make up the “self” called the fluid self: soft data, hard data and core data. Thus, for him, our behavior is made up of the multiple facets of our digital experience: an isotopy emerges from the terminology used to describe the data at the scale of the “self” and that of the computing language including the image of a networked body, pictured as a complex and transparent information system. On socio-digital networks, Chris Dancy claims that his connected objects help him to be “a better human being” and allow him to better understand himself. Moreover, he states on Twitter, “It’s not about your data, it’s about your identity”. His discourse is aimed at convincing others that the Quantified Self used for the purposes of benevolent self-monitoring is accomplishing the Socratic quest for self-knowledge.

In the interviews and images that he publishes on Facebook, he creates the image of a hybrid body that references those of science fiction, by intermingling spirituality, embodied technology and invisibilization of digital interfaces in the environment. Moreover, he declares that having multiple pieces of information on the environment surrounding him, thanks to his connected classes is “like being the Terminator!”. Likewise, a Facebook profile image (Figure 6.7) is a photomontage in which Chris Dancy’s face appears with a fluorescent necklace around his neck, a computer component embedded in his cheek. A “friend” commented on this image by comparing Chris Dancy to Captain Kirk from the film Star Trek.

Figure 6.7. “The mindful cyborg”: the hybrid body and science-fiction imagery. Screen capture of a post by Chris Dancy on Facebook

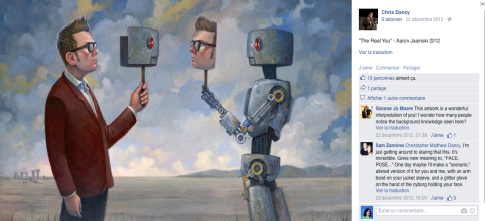

Another profile image is a portrait created by Aaron Jasinski in 2012, in which Chris Dancy is shown in profile, facing a robot (Figure 6.8). He holds a robot mask in his hand while the robot holds a mask with his face. The portrait is titled “The Real You”, which stresses the fact that Chris Dancy represents himself as being half-human and half-robot. It is also interesting to note that a comment posted by a close friend who seems to know him well refers to “this cyborg wearing your face.” The comment seems to signify that Chris Dancy feels closer to a robot than a human, and has constructed a hybrid identity of an “enhanced” human.

Figure 6.8. “The real you”: portrait created by Aaron Jasinski. Screen capture of a post by Chris Dancy on Facebook

All of these elements are disseminated on the multiple platforms which make up his fragmented digital identity, contributing to the promotion of an image of the interaction between humans, information systems and the environment. Chris Dancy moreover proposes the term “Innernet” for picturing a possible future in which the individual interacts with the environment through feedback which the connected objects on and around him send back to him. In this vision of interaction design, the body and the environment become interfaces, and identity is defined by information.

Chris Dancy also specifies the orientation of his approach to self-measurement by distinguishing between Big Brother and Big Mother. According to him, the former system accumulates data about individuals in order to control them, while in the latter system, the collection of data on oneself is done for the purposes of taking control of the data by and for himself. The use of the expression “Big Mother” is a strategy aimed at reinforcing the benevolent dimension of this self-monitoring, as it brings to mind imagery linked to maternity.

A comment published by Chris Dancy on Instagram regarding an image from the application Existence emphasizes the emotional relationship that he maintains with his information technologies. There is a dog peaceably lying down with the following phrase “Are you feeling better today? You weren’t yourself recently.” Chris Dancy comments: “It knows me”. Attributing a human capacity for knowledge, comprehension and compassion to the application underlines the emotional link that he has with this application, characterized by emotional design [NOR 12] focused on both the behavioral and reflexive levels. This user-friendly interface can only reinforce the burying of technologies and the machine’s different layers of calculation, at the same time that it creates one with the user. In addition, the touch screens with which Chris Dancy interacts every day are constructed on “a progressive analogy between human sensoriality and mechanical sensibility, bringing machines closer and closer to bodies” [MPO 13].

Thus, the analysis of these several texts and images published online by Chris Dancy make it possible to understand his relationship with his connected objects, his vision of interaction design and the value system at the heart of this relationship with his devices: physical performance, self-esteem, hybridization (cultural, technological, physical), incorporation and invisiblization of portable information technologies are its main axes. Chris Dancy’s experience constitutes a paradigmatic example of the ideology of transhumanism, whose relationship to technology is made up of a mixture of animism5, anthropomorphism and refers to science fiction imagery.

Chris Dancy’s vision of interaction design oriented toward contemplative computing, calm technology and the attentive environment falls within the continuum of Mark Weiser’s ubiquitous computing project. Chris Dancy’s experience seems to crystallize an emerging trend in our contemporary era, in which the relationship to a world mediated by interfaces is generalized, while the interfaces invisibilize into the environment.

Chris Dancy’s work on the dialectic of the values of connected objects allows an updating of “an axiology and an alignment with social values” [BEY 12]. We can thus picture the way in which connected objects embody the contemporary zeitgeist by offering a relationship to the world mediated by interfaces. The use of Big Data at the individual scale seems to realize the original dream of information technologies and to communicate and accomplish the biopolitical project of cybernetics on the scale of the human body.

From a socio-cultural point of view, Chris Dancy’s portable information technologies transform him into an “interfaced man” centered on a logic of “auto-reading-writing between brain and screen, and auto-regulation of the body” [REN 14a, REN 14b]. The Quantified Self is part of the fantasy of the “datafication of life itself” [CUK 14] and constitutes an ideology that is widely publicized to the point of becoming dominant in the doxa. However, this orientation of personal information technologies is only one possible path [GRA 13] for Big Data that needs to be interrogated.

In the case of Chris Dancy, it is also necessary to mention the ambiguity in his discourse between the promotion of the tools he uses (by incorporating the slogans of the applications in his slideshows presented in his conferences and on Slideshare) and his user experience, knowing that he is an expert in information technologies. Confusion arises about the genre of the discourse (reflective, advertising) and in the roles that he incarnates (consultant, witness, user) which come close to conflicts of interest. This confusion is part of the experiential marketing movement, in which consumers turn into spokespeople for brands (applications in this case).

6.4. Critical perspective and avenues for reflection for reconsidering the use of connected objects and mobile applications in the field of health

At the end of this analysis, it seems apt to go beyond the particular case of Chris Dancy in order to develop reflections on the ethical, institutional and socio-economic challenges related to the use of connected objects and Big Data in the healthcare field. If Chris Dancy’s case is still exceptional today, connected objects are used more and more widely by citizens. To respond to this growing demand, a market in information technologies specializing in health is developing exponentially to the point of becoming a challenge for society which involves not only both the community of researchers in information and communication sciences, engineers and designers, and doctors, but also all citizens more generally. This final part therefore has the goal of critically considering connected objects and applications available on the market, but also envisaging other possible technologies and the way in which they could be created within an ethical and sustainable dynamic, based on a logic of human-centered design.

6.4.1. Ethical and social issues related to data governance

“It always comes with a price…” this saying from the series “Once upon a time” seems appropriate for thinking about the passage from spectacularization of data to the problem of data governance. From an ethical point of view, a tacit contract is created – without it being spelled out – between the citizen and manufacturers of information technologies.

As Dominique Cardon emphasizes in his most recent work, “the subject’s confrontation with the quantification of his behaviors is promoted as an instrument for constructing identity, a personal benchmark” [CAR 05]. In the case of Chris Dancy, his use of Big Data is linked to the three steps of his self-improvement project: lose weight, stay in shape, and most recently be “Zen”. The use of information technologies then falls within the utopia of transparency that the digital permits, one which maintains the idea that “cross referencing of data done by the user himself” allows him to be “administrator of his own data” by becoming a “collector-interpretor” [CAR 05, p. 78]. The user thus becomes master of his data in the face of “state surveillance” and “the instrumentalization of the market.” However, this vision is illusory since, “when individuals take control of their data, they do it in a context of asymmetry of information and the absence of alternatives” [CAR 05, p. 79]. Thus, personal information technologies and Big Data at the individual scale offer many opportunities, but they also pose questions beyond the governance of data. This problem exists in front of a judicial void since there is currently no law that regulates circulation and cross-referencing of data. Furthermore, the digitization and cross-referencing of health data leads to the anonymization of patients, whose data is accessible on the network [MIC 15]. It is at this level that the problem of data regulation by public and legal institutions that protect citizens is raised. “Quantification practices in the health field favor individual micro-management of health to the detriment of a more collective understanding. They make individuals into entrepreneurs of themselves who are responsible for their good or bad health habits, and can distract attention from the environmental and socioeconomic causes of public health problems” [ROU 14].

This system of self-monitoring raises the problem of the digital traceability of personal data. Connected objects call into question the interpretation and use of data from a bioethical, political and socio-economic point of view. Recording physical performances according to the norms and standards defined by manufacturers in connected “health” raises the question of the role of mediation by public institutions and healthcare actors (especially doctors) to frame the use of data and prevent the commercialization of health. This problem entails “algorithmic” [ROU 13] thinking. While the development of Big Data draws on a concept of transparency supposed to empower the individual, data collection techniques in fact threaten the empowerment of citizens. Big Data is initiating a new regime of visibility presented as a neutral goal, while it removes the collectively negotiable neutral perspective for the benefit of mechanical representation, producing norms with which it is impossible to negotiate.

This is why the exponential development of connected objects, much like that of nano- and biotechnologies, involves “the redefinition of the relationships between civil and technological society” [JAR 14, p. 327]. A reflection on the future of human and individual identity in the world of Big Data seems necessary, at a step in the development of biotechnologies where it is still possible to question them. Used only for commercial purposes, these technologies could end with a society of control, via technologies integrated into the privacy of the body. Within the context of privatization of health insurance, connected objects could lead to a commodification of biological and medical formulas, which would be harmful to the less performing of us.

The development of Big Data is also becoming a challenge in terms of marketing, since it permits traceability of consumption on the web and the possibility of predicting the behavior of consumers. This situation is a blessing for the large industrial technology groups: it can lead to a new form of voluntary subjugation, in which the individual becomes the tool of individualized marketing.

The ethical and social questions raised by the massive use of connected objects in the field of health are many. It is first necessary to consider the development of “ubimedicine” – a term suggested by Dr. Nicolas Postel-Vinay (Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou, Paris) to refer to “what could be a medical practice based on the reception and analysis of health data collected voluntarily by the user in multiple times and places”6. This neologism reinforces the fact that this practice was developed outside of the traditional institutional frameworks (such as the consulting room or the hospital room) and follows in the footsteps of ubiquitous computing. We cannot deny that the development of “connected health” is the result of a triple evolution: sociological, technological and politico-economic, made manifest by the lightning-fast expansion of the market of connected objects oriented toward health or well-being. However, this development cannot only remain in the hands of the sector’s manufacturers. It needs to be supervised by doctors, guarantors of the protection of medical confidentiality, and public institutions for the regulation of patient data, as well as the patients themselves; all these must be considered in this digital transformation of the health sector that involves the area of public policy. The White Paper published by the Conseil national de l’ordre des médecins (CNOM), raises two major questions. Doctors insist on the necessity of asking: “to what extent can they [applications] be considered medical devices? Do we have to stipulate specific rules for the protection of the data collected?”7. We can complete this line of questioning by also asking who will be guarantors of data protection. Who can access it and for what purpose? This questioning refers to the problem of regulating the circulation of patient data that involves all healthcare actors (doctors, patients, public and private institutions) who participate in the patient’s course of care. This therefore involves rethinking the French social solidarity model, by considering the way in which the doctor/patient relationship is transformed by the use of connected objects and mobile health applications.

6.4.2. The doctor-patient relationship transformed by connected objects and mobile health applications

With connected objects and mobile health applications, doctor-patient communication is mediated by digital interfaces and the patient data is communicated beyond the medical sphere, especially in the case of the digitized medical file and sharing over a network. Patients become consumers of information services, which profoundly transforms their relationship with healthcare professionals, but also the way in which data related to health is produced.

As we saw in the beginning of this study, it is necessary to distinguish medical devices from anthropotechnics. The pattern of consultation for these two types of technology is radically different. In the first case, a patient has consulted a doctor who performs a diagnostic and proposes treatment including the collection of certain data using digital and non-digital tools. In the second, it’s the consumer who initiates both the diagnosis and treatment since he self-evaluates using anthropotechnics and information services to transform his body by himself. The goals are not the same because medicine relies on a code of ethics that falls within a legislative framework. The Big Data used in health thus calls into question two pillars of medicine: medical confidentiality and “the search for the best benefit/risk balance for health in keeping with the patient’s autonomy” [GOF 13, p. 101]. This is how the doctor-patient relationship is evolving toward a “professional-client relationship” or even a “service delivery relationship” [GOF 13, p. 96].

In addition, the positivism that is exacerbated by technologies that are more and more user-friendly also maintains the illusion of the possibility of making a medical diagnosis which does not require any human mediation, or even that is more performing than a healthcare professional. This therefore questions the role of scientific mediation, and also brings up the problem of legal responsibility for the interpretation of health data by a third party that does not belong to medical professionals. When it comes to information and communication with the patient, promotional discourse maintains confusion about the medical goal of “health” applications, with a generalized trend with manufacturers in the information technology sector toward medicalization of connected objects, or at least the claim of a health benefit. There is thus a problem with the deficit of information about m-health, even though consumers, lost in the jungle of connected objects available on the market, are waiting for advice and recommendations from healthcare professionals. This problem of misinformation resembles the arrival in the market in the agro-food industry of nutraceuticals, which were marketed as food having properties similar to medications that provided providing health benefits.

The use of digital devices in the field of health “could be an effective resource for cooperation between the person and his or her doctor, more generally with the healthcare professionals that oversee care” [CON 15, p. 33]. Nevertheless, it is more necessary than ever for doctors to participate in the conception and setting up of digital medical devices, as well as in the reflection on the regulation of health data, in dialogue with public and private institutions, and in the social interest of the patient. This also entails offering a digital education for doctors and patients, which returns society more generally to the problem of digital literacy and digital humanities. On the one hand, doctors need to be trained, within the framework of their curriculum, in the use of digital medical devices (comprising connected objects and mobile health applications). “The training must deal not with the tool but with its integration of ethics and professional standards into the medical practice itself, for the benefit of the patient.” On the other hand, this digital education also involves patients, who must be encouraged to “promote use respectful of rights and freedoms, confidentiality and the protection of personal data” [CON 15, p. 34].

Thus, connected objects and mobile health applications could constitute a socially useful complement to consultation in many cases, involving the “monitoring of a metabolic disruption such as diabetes, a diet designed for weight loss, assistance with therapeutic education, support or maintenance of autonomy or monitoring of physical and athletic activity” [CON 15, p. 34]. It is nevertheless necessary to define “between the doctor and the patient, a framework of “appropriate use” of the application or connected object during its integration into the field of care and treatment” [CON 15, p. 34]. This is why doctors and more generally healthcare professionals need to address the problem of connected health in order to offer solutions adapted to their needs and to those of their patients. This social project imagines “the realization of a double evaluation, combining value-in-use and medico-economic value” [CON 15, p. 33]. Although the mediation of doctor/patient communication is increasing with the development of the use of communicating objects and digital interfaces, it is nevertheless necessary for digital mediation to be framed by human mediation, by placing the healthcare professionals at the heart of the debate over the use of these new devices.

6.4.3. The necessity of considering the point of view of doctors and healthcare professionals

Several reports and investigations published at the national8 and international9 scale attest to a growing preoccupation with the development of connected and mobile health on the part of healthcare professionals. These dialogues have given way to analysis of the use of digital devices within the community of doctors and patients, some of which have led to concrete propositions that seem to us important to consider. To develop reflections on the use of connected objects and health applications serving the needs of patients and doctors it is indispensable to listen to these propositions of healthcare professionals. Among the available professional literature, the propositions of the CNOM are particularly interesting, because they synthetically present workable solutions to accompany the surge of connected objects within the framework of the doctor/patient relationship, in particular within the context of office visits.

At the moment, there is no certification in France concerning the use of applications and connected objects that are not recognized as medical devices. In addition, the principal goal of CNOM’s propositions is to better inform patients about the functions and conditions of use of these devices. To provide the means of carrying out this project of education in the use of digital devices, CNOM has developed six propositions [CON 15, pp. 6–7]. The first proposition is aimed at “defining proper use of mobile health in the service of doctor-patient relationships” which entails defining an ethical framework for integrating m-health devices into medical care. From this perspective, another proposition reinforces the necessity of “watching over the ethical use of connected health technologies” by attracting attention to economic models based on the valorization of patient data and risk threatening national solidarity. When it comes to the designers and manufacturers of connected health, CNOM advises “promoting appropriate, progressive and European regulation” and to “pursue scientific evaluation” by experts independent of the sector’s manufacturers. It seems important to point out the importance of the necessity for applications and connected objects to meet a certain number of standards in order to be recognized as medical devices, which entails both the challenges of regulation but also interoperability between devices. For patients, the major challenge of m-health is to “develop digital literacy” especially concerning the mastery of the advanced functions of digital devices in terms of confidentiality and the protection of personal data. Finally, it also involves initiating a “national e-health strategy”, and now m-health, which involves French and European political decision-makers in the healthcare field to clarify the governance of health data and respect the confidentiality of citizens’ personal data and the necessity of their consent for their use. This last proposition asks us to consider digital devices “not as an end but as a group of methods making it possible to improve access to care, the quality of treatment, the autonomy of patients”. It clearly emphasizes the necessity of initiating a debate between actors in public policy, doctors and patients, who must participate in the deliberations over the use of their health data.

Taking users into account (doctors and patients especially) then encourages a move toward a qualitative approach and a form of research making it possible to offer solutions adapted to the needs of each of the stakeholders of an m-health project.

6.4.4. Envisaging other paths for m-health technologies based on the anthropology of communication and social innovation by design

Interaction design’s anthropological approach can contribute to the development of a critical reflection on the dominant models of interaction design only focused on technological or economic innovation. This approach constitutes a constructive “techno-critique” [JAR 14] for offering alternative models of digital technologies in the field of health. Digital technologies and their identification as “new” technologies must be analyzed as sociotechnical and political devices. From this perspective, the works of anthropologist Lucy Suchman constitutes an enlightening avenue for research for highlighting the necessity of an approach that takes the quality of the interaction between human, digital interfaces and the environment into account. In an article dedicated to the links between anthropology and digital design, Lucy Suchman insists on the need to develop a “critical anthropology of design that contributes to the emergence of a critical practical technique” [SUC 11, p. 16]. From this perspective, it is pertinent to analyze connected objects and health applications not only as “intelligent machines” to which humans delegate a part of their social practice, but also as an “embodied form of social practice” [SUC 11, p. 8]. This approach makes it possible to take into account the interaction that takes place between users and their material goods and social environments, by considering the environment as a situational mediation that plays a role as important as technological mediation, in the experience offered to the user.

The analysis of human-machine interaction by the anthropology of communication and design can thus contribute to the reflection on “human ecology” understood as the sum of interactions that take place between humans and their environments, both natural and artificial at the same time [FIN 15] and to the development of concepts, methods and tools in the field of social and digital innovation. To develop the analysis of the interaction between digital devices, users and their environment, it is necessary to take into account the fact that connected objects, like computers, are “physically incarnated and incorporated in a context in such a way that their capacities and their limits depend on a physical substratum, an environmental situation” [SUC 11, p. 7]. Works coming from the anthropology of communication are interesting for the design of digital health technologies, and in particular the possibility of returning to the works of Erving Goffman in Rites d’interaction, which have been considerably transformed by digital technology in the case of connected health. The concept of frame proposed by this researcher is pertinent for rethinking the doctor/patient relationship, the relationship of the patient with his or her own health data, or the communication between patients and health institutions. This deep qualitative analysis of the rite of interaction that is the consultation would make it possible to offer new forms of design in the space of a medical office, more adapted to communication mediated by digital interfaces, and the imperatives of therapeutic education of patients in the use of digital medical devices.

It would therefore seem wise to develop, based on a critical approach to the dominant digital devices in the m-health sector, a form of interdisciplinary research capable of contributing to the reflection and the conception of innovative digital technologies from a social and environmental point of view which is rooted in the problem of informational ecology. Researchers in humanities and social sciences need to be involved in this reflection, by the side of specialists in medical disciplines, in order to participate in the emergence of other models of digital technologies and interaction design in the field of m-health.

The criticisms and fears related to the current path of technology can be seen as the “symptom of a crisis of confidence requiring the setting up of structures of dialogue between businesses, publics and profane powers” [JAR 14]. Design understood as a discipline of the project, is a pertinent approach that is complementary to critical theories of information and communication sciences. Human-centered approaches (human-centered design) are particularly interesting for organizing a dialogue on a major topical issue that concerns every citizen. Human-centered design is not limited to design centered on the user, even if taking use into account plays an important role. Human-centered design is “research on what can support and reinforce the dignity of human beings and the way in which they live in diverse social, economic, political and cultural circumstances” [BUC 01, p. 35]. In that respect, “the quality of the design is distinguished not just by technical skill of execution or the aesthetic vision, but above all by the moral and intellectual goal toward which technical and artistic skill is directed” [BUC 01, p. 26]. In this respect, co-design with stakeholders (doctors, patients, public and private health institutions) would make it possible to offer solutions adapted to specific cultural features (both local and national) and to the needs of the users by taking into account social, economic and ethical imperatives. This approach to technologies through design and the anthropology of communication thus makes possible the movement from a logic of technological innovation toward a logic of social innovation.

Social innovation is a concept that is reappearing today in the scientific debate, notably in the field of design. This dimension is not really new, insofar as the central problem of design is to explore ways in which to improve the world’s livability. It reconnects rather with the essence of design, understood as a discipline of the project, in particular in as the works of Bauhaus, Victor Papanek, or Alain Findeli show. Several definitions of social innovation exist and, as much as the field has been under debate since the beginning of the 2000s, we can nevertheless note three characteristics common to social innovations [VIA 15]. They are not primarily commercial and are located on the side of the common good because their beneficiaries are collective. They are created with the goal of responding to social needs. And they rely on new forms of governance in which the beneficiaries are involved in a participative way, which transforms social relationships. In this respect, social innovation includes a sociopolitical dimension through the recognition of the power of individuals and communities to plan and act. It entails rethinking traditional project management methods by involving new actors, beyond the industrial and economic sectors, particularly as a result of co-design methods.

The return of the social in design seems above all to signal the desire of certain researchers and designers to break from industrial design and be part of a logic of social innovation, anchored in the problems of contemporary society. Indeed, reflection on social innovation by design is connected to that of sustainable development and falls within the context of the current transition that we are living in our hypermodern societies. As Ezio Manzini [MAN 07] emphasizes, the mission of design is to support the way in which individuals redefine their existence in individual self-directed or collective projects. The role of the designer is therefore to create conditions favorable to collaborative work in order to support the process of social and societal change.

Social innovation by design is thus clearly distinguished from technological innovation by putting the concerns of the individual and his or her aspirations at the center and by relying on a dynamic of horizontal, transversal and participative research. This form of research is located on the border of observational and interventional research, by simultaneously offering a close observation of the uses of an existing device and a new proposition for conception of a device adapted to the needs of the stakeholders in a project. Alain Findeli has notably proposed a model of design research called “project research” [FIN 15], in which the research is conducted within the framework of a design project that constitutes the field of research. Project research in design is particularly interesting for contributing to the reflection on alternate forms of digital technologies in the service of the needs of doctors and patients in the field of m-health. At the crossroads of humanities and social sciences, design moreover makes it possible to imagine transformations that are not only technological, but also social, cultural and communicational brought about by the digital.

Project research in social and digital innovation and by design can thus contribute to the criticism of the dominant models of digital design centered only on technological or economic innovation, and above all the emergence of other paths [GRA 13] of digital technologies and interaction design, in the service of the common good. Social and digital innovation thus appears as “a type of collaborative innovation in which innovators, users and communities collaborate with the help of digital technologies in order to co-create knowledge and solutions that respond to a wide range of social needs”10. Thus, social and digital innovation is an apt approach for rethinking informational ecology through design in the field of health.

From this perspective, we can envisage the development of an interdisciplinary research program, at the intersection of humanities and social sciences, medical science, engineering sciences and design sciences to contribute to the field of reflection and conception of m-health. The goal of this program would be double: on the one hand it would involve studying the use (and misuse) of connected objects and specialized applications in the field of m-health and, on the other hand, to use project research to contribute to the development of digital devices that integrate an ethical and social dimension from their conception. Starting from a logic of co-design between the different stakeholders in the sector, it would involve initiating a collaborative design process between doctors, patients, public and private institutions. The problem of digital design joins that of public policy design once the devices studied and produced come from a public health policy that needs to be questioned in order to be updated. On the part of users, this program would also allow the development of therapeutic education for patients through digital and human mediation, on the one hand by observing how digital interfaces and connected objects transform the doctor/patient relationship, and on the other by offering new digital tools, based on a logic of human-centered design. As a complement to the observational study on the use of connected objects and digital interfaces in the field of health, the interventional study would have the goal of testing a digital device to serve the needs of stakeholders, which are the doctors and patients, which could contribute to the search for solutions. The research program would include three phases of research (qualitative research, conception, implementation), by articulating theory and empirical data, effective conception and production of a digital device by and for the beneficiaries of the m-health project. This type of project research would finally make it possible to place the role of digital medical devices within a more global system of education and prevention, by replacing the human at the center of its concerns.

6.5. Conclusion

To conclude, there is an ambiguity maintained by promotional discourse between m-health and Quantified Self. Portable information technologies used in the Quantified Self fall within the continuity of this history of information technologies and incorporate anthropotechnics. To respond to the problem, we can say that connected objects and the applications of the Quantified Self transform the relationship to body and to its representation. The body becomes in effect quantified and quantifiable, transparent and readable. Thus, the Quantified Self and the Internet of Things transform the body into a networked resource. From a critical perspective, we can ask if the body and all of existence can be reduced to a sum of data and “information behaviors” [PUC 14].

Analysis of Chris Dancy’s use of communicating objects has made it possible to comprehend the dominant ideology in the field of information technologies and interaction design. This ideology draws on an image of technologies oriented toward transhumanism and emotional interaction design. It is also part of the legacy of the ubiquitous computing project developed by the beginning of the 1990s in the United States. It also anticipates the incorporation of technologies by drawing on an imagery tinged with animism and anthropomorphism, and a symbiotic relationship between interfaces, humans and their environment.

This immersion in our private lives through our behavioral and computer data must be placed within the “full vision” [WAJ 10] created by the multiplication of screens, symptomatic of our era’s zeitgeist. We can critically consider the future of Big Data in this quest for total transparency: “do we consider this technological path as a social evolution? Is it the dream of every citizen to transform his body into a connected object, into a statistical body, network resource available as open-data, or even into an API?” The extreme experience of controlling his own data recently led Chris Dancy to have a real identity crisis: he has been “devoured by his own data” [RIC 16] as he explained it in his recent interviews.

Furthermore, beyond analysis of Chris Dancy’s case, we have raised, in the last part of the article, the ethical and social challenges related to the governance of data. This entails rethinking m-health considering social support, a distinctive feature of the French healthcare system.

We have also sought to explain the necessity of developing, by completing a critical analysis of dominant technologies in the m-health sector, a form of participative research, falling along the lines of project research [FIN 15]. It would make it possible to address the current problems of doctors and patients, whose relationship is transformed by the surge in connected objects, in order to offer alternative solutions.

Other paths [GRA 13] remain to be imagined in the field of portable information technologies specializing in health. An interesting pathway to explore would be that of “clearing desirable paths for transforming “humanitude” and the mechanisms of action that would lead there (political, social, educational)” [GOF 13]. Rethinking mobile applications and connected objects in a design logic centered on the human and oriented toward social innovation seems to be a pertinent direction for research. Research in humanities and social sciences can thus contribute to the development of socially innovative digital devices, by taking into account the needs of users, considered to be stakeholders in a public health project. From a socio-political point of view, project research in design and m-health is a participative research method that allows citizens to get involved in the current public debate about the management of personal health data, in order to contemplate solutions centered on patient interests and in dialogue with healthcare professionals.

6.6. Bibliography

[BER 67] BERTIN J., Sémiologie graphique: diagrammes, réseaux, cartes, Mouton, Paris, 1967.

[BEY 12] BEYAERT-GESLIN A., Sémiotique du design, PUF, Paris, 2012.

[BON 15] BONENFANT M., PERRATON C., Identité et multiplicité en ligne, Presses Universitaires du Québec, Montreal, 2015.

[BOU 02] BOULLIER D., “Objets communicants, avez-vous donc une âme?”, Les Cahiers du numérique, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 45–60, 2002.

[BUC 01] BUCHANAN R., “Human Dignity and Human Rights: Thoughts on the Principles of Human-Centered Design”, Design Issues, vol. 15, no. 3, p. 35, 2001.

[CAR 05] CARDON D., A quoi rêvent les algorithmes?, Le Seuil, Paris, 2005.

[CAT 16] CATOIR-BRISSON M.-J., CACCAMO E., “Métamorphoses des écrans: invisibilisations”, Interfaces numériques, vol. 5, no. June 2, 2016.

[CAT 12] CATOIR M.-J., LANCIEN T., “Multiplication des écrans et relations aux médias: de l’écran d’ordinateur à celui du smartphone”, MEI, no. 34, pp. 53–65, 2012.

[CEN 14] CENTRE D’ETUDES SUR LES SUPPORTS DE L’INFORMATION MEDICALE, Baromètre annuel sur les usages digitaux des professionnels de santé, CESSIM-Ipsos, 2014.

[CLA 14] CLAVERIE B., “De la cybernétique aux NBIC: l’information et les machines vers le dépassement de l’human”, Hermès La Revue, no. 68, pp. 95–101, 2014.

[COM 09] COMYN G., “La e-santé: une solution pour les systèmes de santé européens?”, Les dossiers européens, no. 17, May–June 2009.

[COU 15] COUTANT A., STENGER T. (eds.), Identités numériques, L’Harmattan, Paris, 2015.

[CNI 14] CNIL, “Quantified-Self, m-santé: le corps est-il un nouvel connecté?”, CNIL, available at: http://www.cnil.fr/linstitution/actualite/article/article/quantified-self-m-sante-le-corps-est-il-un-nouvel-objects-connecte/, 2014.

[CON 15] CONSEIL NATIONAL DE L’ORDRE DES MEDECINS, Santé connectée: de la e-santé à la santé conectée, CNOM White Paper, January 2015.

[CUK 14] CUKIER K., MAYER-SCHÖNBERGER V., Big data: la revolution des données est en marche, Robert Laffont, Paris, 2014.

[DEM 02] DEMASSIEUX N., “Au-delà de la 3G, les communicating objects”, Les Cahiers du numérique, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 15–22, 2002.

[DEN 05] DENI M., “Les objects factitifs”, in FONTANILE J., ZINA A. (eds), Les objects au quotidien, Presses Universitaires des Limoges, 2005.

[FIN 15] FINDELI A., “La recherche-projet en design and la question de recherche: essai de clarification conceptuelle”, Sciences du Design, no. 1, pp. 43–55, 2015.

[FLO 90] FLOCH J.-M., Sémiotique, marketing and communication, PUF, Paris, 1990.

[GAU 00] GAUDREAULT A., MARION P., “Un média naît toujours deux fois…”, Sociétés et Representations, no. 9, pp. 21–36, 2000.

[GOF 13] GOFFETTE J., “De l’humain à l’humain augmenté: naissance de l’anthopotechnics”, in KLEINPETER E. (ed.), L’humain augmenté, CNRS Editions, Paris, 2013.

[GOF 06] GOFFETTE J., Naissance de l’anthopotechnie: De la biomédecine au modelage de l’human, Vrin, Paris, 2006.

[GRA 13] GRAS A., Les imaginaires de l’innovation technique, Manucius, Paris, 2013.

[JAR 14] JARRIGE F., Technocritiques: du refus des machines à la contestation des technosciences, La Découverte, Paris, 2014.

[LAM 14] LAMONTAGNE D., “La culture du moi quantifié – le corps comme source de données”, ThotCursus, available at: http://cursus.edu/article/22099/culture-moi-quantifie-corps-comme-source/#.U_dcR0sQ4b8, 2014.

[LAN 10] LANCIEN T., “Multiplication des écrans, images et postures spectatorielles”, in BEYLOT P., LE CORFF I., MARIE M. (eds), Les images en question, Cinéma, télévision, nouvelles images, PUB, Bordeaux, 2010.

[MAN 07] MANZINI E., “Design Research for Sustainable Social Innovation”, in MICHEL R. (ed.), Design Research Now: Essays and Selected Projects, Birkhäuser, Basel, 2007.

[MAN 15] MANZINI E., Design, When Everybody Designs, an Introduction to Design for Social Innovation, MIT Press, Cambridge, 2015.

[MER 13] MERZEAU L., “L’intelligence des traces”, Intellectica, no. 59, pp. 115–135, 2013.

[MIC 15] MICHAL-TEITELBAUM C., “Big Data et Big Brother. Données et secret médical, vente de dossiers médicaux aux sociétés privés et médecine personnalisée”, available at: http://docteurdu16.blogspot.fr/2015/04/Bigdata-et-big-brother-donnees-et.html, 2015.

[MOR 62] MORIN E., L’esprit du temps, Grasset-Fasquelle, Paris, 1962.

[MPO 13] M’PONDO DICKA P., “Sémiotique, numérique et communication”, RFSIC, no. 3, 2013.

[NOR 12] NORMAN D., Design émotionnel, De Boeck, Brussels, 2012.

[OMS 11] ORGANIZATION MONDIALE DE LA SANTÉ, “Health New Horizons for Health Through Mobile Technologies”, Global Observatory for eHealth series, vol. 3, 2011.

[OMS 46] ORGANIZATION MONDIALE DE LA SANTE, “Définition de la santé, Préambule à la constitution de l’OMS” Conférence internationale sur la Santé, New York, United States, June 19–22, 1946.

[PAP 85] PAPANEK V., Design for the Real World: Human Ecology and Social Change, Academy Chicago Publishers, Chicago, 1985.

[PIN 02] PINTE J.-P., “Introduction”, Les Cahiers du numérique, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 9–14, 2002.

[PRI 02] PRIVAT G., “Des objets communicants à la communication ambiante”, Les Cahiers du numérique, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 23–44, 2002.

[PUC 14] PUCHEU D., “L’altérité à l’épreuve de l’ubiquité informationnelle”, Hermès La revue, no. 68, pp. 115–122, 2014.

[REN 14a] RENUCCI F., “L’homme interfacé, entre continuité et discontinuité”, Hermès La revue, no. 68, pp. 203–211, 2014.

[REN 14b] RENUCCI F., LE BLANC B., LEPASTIER S., “L’autre n’est pas une donnée. Altérités, corps and artefacts”, Hermès La revue, no. 68, 2014.

[RIC 16] RICHARD C., “L’homme le plus connecté du monde s’est fait dévorer par ses données”, L’Obs-Rue 89, http://rue89.nouvelobs.com/2016/06/17/lhomme-plus-connecte-monde-sest-fait-devorer-donnees-264377, June 17, 2016.

[ROU 14] ROUVROY A., “Avant-Propos - Du Quantified-Self à la m-santé: les new territoires de la mise en données du monde”, Cahiers IP de la CNIL: Le corps, nouvel object connecté, no. 2, pp. 4–5, 2014.

[ROU 13] ROUVROY A., BERS T., “Gouvernementalité algorithmique et perspective d’émancipation”, Réseaux, no. 177, 2013.

[SAL 08] SALMON C., Storytelling, la machine à fabriquer des histoires et à formater les esprits, La Découverte, Paris, 2008.

[SOO 11] SOOJUNG-KIM P., “Contemplative Computing”, Conférence du Microsoft Research, available at: https://www.academia.edu/635387/Contemplative_Computing, Cambridge, United States, 2011.

[SUC 11] SUCHMAN L., “Anthropological Relocations and the Limits of Design”, Annual Review of Anthropology, no. 40, pp. 1–18, 2011.

[TRE 14] TRELEANI M., “Bientôt la fin de l’écran”, INA Global, no. 1, pp. 64–70, 2014.

[VIA 15] VIAL S., Le design, PUF, Paris, 2015.

[VID 13] OBSERVATOIRE VIDAL, Usages numériques en santé, Deuxième baromètre sur les médécins utilisareurs de smartphone en France, May 2013.

[WAJ 10] WAJCMAN G., L’œil absolu, Denoël, Paris, 2010.

[WEI 91] WEISER M., “The Computer for the 21st Century”, Scientific American, vol. 265, no. 3, pp. 66–75, 1991.

Chapter written by Marie-Julie CATOIR-BRISSON.