Chapter 3

How Investment Bankers Sell Companies

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Digging into the specific tasks investment banks undertake when selling a company

Digging into the specific tasks investment banks undertake when selling a company

![]() Finding out what’s included in an IPO prospectus

Finding out what’s included in an IPO prospectus

![]() Identifying the keys to a successful IPO

Identifying the keys to a successful IPO

![]() Understanding how sell-side research aids in the process of selling a stock

Understanding how sell-side research aids in the process of selling a stock

![]() Determining who sell-side research analysts serve

Determining who sell-side research analysts serve

![]() Diving into a sample sell-side research report to understand its purpose

Diving into a sample sell-side research report to understand its purpose

Investment banking isn’t exactly a glamorous business. When was the last time you heard a 6-year-old say she wants to be an investment banker when she grows up? Much of what investment bankers do is lucrative, but it’s behind the scenes and tucked in the back rooms of the financial system.

If there’s an area where investment bankers really shine, it’s in the process of selling a company to the public for the first time in an initial public offering (IPO). The IPO is one of the few times when the general public has a chance to see and interact with investment banks and the financial products they’re selling and see the role investment bankers play in the economic machine.

We introduce the importance of the IPO in Chapter 2. In this chapter, we delve more deeply into the IPO process, taking a look at what investment banks look for when selling a company in the public markets. One of the key jobs of investment banks in bringing a company to the public markets is assisting in creating a document that spells out the details of an offering, called the prospectus. Here, we explore the prospectus in detail, along with the ways investment bankers can make sure an IPO goes off smoothly.

Closely linked to the IPO process is the sell-side analysis function of many investment banks. These operations help complete the process of selling the company that investment banks are often tasked with.

Also in this chapter, you get an understanding of the types of research that go into a research report. We dissect and analyze a sample report to illustrate how investment banks dig into a company’s financials and prospects so they can either recommend a security or advise against it.

Getting Companies Ready for Sale on Public Markets

There comes a time in a company’s life when going public is often the best option. When a company gets big enough, and a broad enough audience of investors is lined up to buy a piece of a company, it’s time to strongly consider an IPO.

When a company goes public, it carves itself into pieces that investors in the general public can buy. Just about every stock you can invest in, at one point, first sold its stock in an IPO.

Companies often turn to IPOs when

- Bank loans are too expensive. When a company gets bigger, borrowing from the bank becomes a relatively costly form of raising money.

- Venture capitalists are too onerous. Venture-capital firms are great sources for young companies that don’t have many options. But these investors insist on big ownership stakes, stripping the entrepreneur’s ownership in the companies. Venture-capital funds are pools of money from private investors who are looking to hit it big.

- Venture capitalists or other private investors want to cash out. Venture capitalists often buy companies with the idea that they’ll sell them once they get big enough to attract public investors. The IPO is a way for venture capitalists to cash in on their investment, so they can put that money into another small company. Private investors, such as private-equity firms, also urge companies to sell shares to the public so they can cash in.

- Bonds are too expensive. Young companies can sell bonds to raise money. But bond investors are a nervous lot, and they tend to demand high rates of return on companies that don’t have a long-term, proven track record. Borrowing this way, especially for relatively unproven companies, can often be prohibitively expensive. Also, bonds must be repaid with interest. A young company may be reluctant to sign up for a deal that requires it to make routine interest payments when its cash flow may be uncertain.

After companies exhaust their normal avenues for raising money, that’s when IPOs come into play. IPOs are a way for companies to get investment capital from investors, who want to be owners. These owners are happy to get a piece of the company and don’t even require a routine payment of cash.

Meeting the requirements to make an IPO happen

Investment bankers can concoct just about any financial product out of thin air. And some of these products indeed make investors’ money go poof (as you find out in Chapter 19). But IPOs aren’t created out of nothing. An IPO at its core requires a willing company that’s looking to raise money by selling part of itself to willing investors.

And for an IPO to be successful — in that it attracts ample investors to pay a healthy price for the stock — the bar is even higher. A few characteristics of a company that is often a prime candidate for a successful IPO includes being in the following:

-

An industry investors are interested in: IPO investors often get infatuated with certain investment themes. When an industry catches the attention of investors, there’s usually ample appetite for several key players to go public as investors lap up the shares like hungry wolves.

The best example of an industry that IPO investors couldn’t get enough of was the Internet. During the late 1990s and early 2000s, just about any company with an e before its name or a dot-com after it was able to sell stock to the public and get a huge valuation. Table 3-1 shows how Internet companies ruled the IPO market in 1998 through 2000.

The best example of an industry that IPO investors couldn’t get enough of was the Internet. During the late 1990s and early 2000s, just about any company with an e before its name or a dot-com after it was able to sell stock to the public and get a huge valuation. Table 3-1 shows how Internet companies ruled the IPO market in 1998 through 2000.TABLE 3-1 When Internet IPOs Ruled the Market

Year

Total Number of IPOs

Number of Internet IPOs

Percentage of IPOs That Were Internet Companies

1998

322

40

12.4%

1999

504

272

54.0%

2000

397

149

37.5%

Source: Jay Ritter, University of Florida (

http://bear.warrington.ufl.edu/ritter/ipodata.htm) -

A fast-growth period of its lifecycle: Companies often love IPOs because they can raise money without actually agreeing to ever give that money back or even pay interest on it. IPOs can be a great deal for the company compared with other ways of raising money, which require interest payments. That said, investors are a fickle bunch. If they’re not going to get paid a predictable return, they generally want the promise of something else. And that something else is usually a piece of a company with explosive growth. Investors routinely examine a company’s growth rate to make sure it’s expanding faster than the average company to see if it’s worth investing in.

Hopes for rapid growth was one of the keys of the May 17, 2012, IPO of Internet sensation Facebook. The online social-networking company raised more than $16 billion from investors, making it the fourth largest U.S. IPO of all time and the biggest technology IPO ever at the time, according to Renaissance Capital. Facebook was certainly putting up huge growth. The company posted 154 percent revenue growth in 2010 and 88 percent revenue growth in 2011. Those massive rates of growth were more than enough to get the attention of investors. But sometimes companies go public when they’re peaking so they can sell their shares at a rich price. More than a year after its IPO, shares of Facebook were still below the $38-a-share price they fetched when they were initially sold to initial investors. But once the company proved to investors it indeed could grow at breakneck speed, shares took off. As of late 2019, Facebook shares topped $185 each, making the company worth more than $530 billion.

Hopes for rapid growth was one of the keys of the May 17, 2012, IPO of Internet sensation Facebook. The online social-networking company raised more than $16 billion from investors, making it the fourth largest U.S. IPO of all time and the biggest technology IPO ever at the time, according to Renaissance Capital. Facebook was certainly putting up huge growth. The company posted 154 percent revenue growth in 2010 and 88 percent revenue growth in 2011. Those massive rates of growth were more than enough to get the attention of investors. But sometimes companies go public when they’re peaking so they can sell their shares at a rich price. More than a year after its IPO, shares of Facebook were still below the $38-a-share price they fetched when they were initially sold to initial investors. But once the company proved to investors it indeed could grow at breakneck speed, shares took off. As of late 2019, Facebook shares topped $185 each, making the company worth more than $530 billion. -

Strong competitive advantage: If investors are going to take a risk on shares of a newly established public company, they want to make sure they’re protected a bit. One way investors can feel good about their investment is betting on a company that has scarce competitors and very high barriers to entry (meaning, it would be costly for a competitor to take on the company in the product marketplace).

Many massive IPOs fit this category. Visa and UPS are the no. 1 and no. 11 largest U.S. IPOs ever, having raised $17.9 billion and $5.5 billion, respectively. Both of these companies really only have a handful of serious competitors and are protected by the fact that massive investments in equipment would be needed for anyone to even dream about taking them on.

Many massive IPOs fit this category. Visa and UPS are the no. 1 and no. 11 largest U.S. IPOs ever, having raised $17.9 billion and $5.5 billion, respectively. Both of these companies really only have a handful of serious competitors and are protected by the fact that massive investments in equipment would be needed for anyone to even dream about taking them on.

Writing the prospectus

The most important document the company and the investment bankers must produce to make an IPO happen is the prospectus. The prospectus is the massive document that lists all the opportunities, risks, and financial details about the company that’s selling stock to the public. It’s available to investors, regulators, and other interested parties.

For most IPOs, the prospectus can be an immense document that spans hundreds if not thousands of pages. Creating the document is one of the major tasks that investment bankers are paid to do when bringing an IPO to market. The prospectus typically contains a wealth of information that falls into several key sections, which we outline in this section.

Summary

At the top of a prospectus, the investment bankers lay out the main details an investor should be concerned with. Here, in the summary section, investors learn about the company’s intentions from the deal. Of most interest to investors — and investment bankers — is how many shares the company plans to sell and at what price.

In this part of the prospectus, investment bankers also try to demonstrate why the company is looking to sell stock. It’s pretty typical for the investor to get a taste of the size of the company’s target market. The summary is also a common place for the company’s management team to lay out their broad objectives for the company.

Risk factors

If there is a “cover yourself” section of a prospectus, it’s the risk factors area. In this part of the prospectus, the company and its investment bankers warn investors of all the possible things that could go wrong and cause the value of the new stock to crumble. Investment bankers may not list the risk of a zombie invasion, but they list just about everything else.

Here, companies are practically preparing their “I told you so” defense in case the stock doesn’t work out. You’ll find references to just about anything that could possibly happen in this section, along with loads of canned, boilerplate warnings that appear to be cut-and-pasted from filings.

Industry data and other metrics

Just as a rising tide lifts all boats, investors know that companies are often only as good as the industries they’re in. If you invest in a grocery store company, investors know to expect relatively thin profit margins (meaning, the company will likely only retain a small slice of its total revenue as profit, because that’s how the industry works).

And because the performance of the industry has such a large bearing on how well a company does, it’s a critical aspect of the prospectus. Investors will find a description of the financial measures that are most important in the industry, as well as an outline of how the company going public stacks up.

Use of proceeds

When a company goes public, it can raise hundreds of millions if not billions of dollars overnight. Literally. Isn’t capitalism wonderful? But hopefully the money isn’t being raised so the CEO can throw a heck of a party or buy a billion black hoodies. The money being generated by the IPO is for some sort of corporate purpose, and it’s in this section of the prospectus that this purpose is revealed to investors.

Normally, a young company going public is raising money because it needs cash to expand and grow. But there are other reasons why a company may go public, including to pay off part of its debt, to purchase another company, or to allow its employees to sell their shares and raise money. Whatever the reason, it must be outlined in detail here.

Capitalization

The capitalization structure of a company is critical to IPO investors. The capitalization structure is a description of the types of financing that were used by the company to raise money. The typical company has a blend of forms of financing ranging from bank loans to outstanding bond debt and perhaps preferred stock (a special type of stock that typically pays a supersized dividend and has greater claims to the company than the regular, common stock that’s issued by companies).

Financial data

Some hard-core financial types skip past many of the sections of the prospectus listed earlier and go straight for this part. Here’s where you find the company’s financial statements (detailed financial records that show how much the company made in profit and revenue, as well as everything it owns and owes). You can find more information about these financial statements, including the income statement and balance sheet, in Chapter 7.

Management’s discussion and analysis of financial condition

Wow, that’s a mouthful. But that’s the section’s official name. Most investment bankers refer to this important section of the prospectus by its acronym, MD&A. It’s in this section of the prospectus that the company’s management team, with the help of the investment bank, steps through the financial statements, almost line-by-line, with full description. Any numbers that are a little offbeat or unusually large or small should be detailed in this section.

Business

If investors are seriously considering forking over money to buy a piece of a company, they’d better know at least what the company does. The business section of the prospectus is the place where the company explains its reason for being. The company often explains the products it makes or the services it provides and why customers deem them worthy to be bought.

Management

A company is only as good as the people running the place. And that’s not a detail missed by IPO investors. The management team of a young company is critical. Decisions made by the top brass will largely determine if the company is able to head off the inevitable challenges. In the management section of the prospectus, you find a listing of all the top management team members — usually the chief executive officer (CEO), chief operating officer (COO), chief financial officer (CFO), and the members of the board of directors (the group of experts who are supposed to look out for the interests of investors and oversee the management). In the management portion of the prospectus, you also find a short biography on all the top people at the company, including their ages. Want to feel old? Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg was just 27 according to the company’s prospectus when the company was going public.

Executive pay

The CEO and other members of the management team aren’t running the company you’re looking to invest in out of the goodness of their hearts. The managers of top companies are paid, usually huge sums of money, for taking on the job. In this section of the prospectus, investors find out exactly how much these people are being paid.

Related-party transactions

Double-dealing may be typical in mystery novels, but that’s exactly the kind of thing you don’t want going on at a company you’re looking to invest in. The trouble with IPOs, though, is that many of these companies trace their roots to being practically family business. Many young companies, even after going public, may have complicated business relationships between founders, their families or friends. All these tangled dealings must be highlighted and explained as related-party transactions.

Principal and selling shareholders

When you buy shares of an IPO, you’re buying those shares from someone. If a company is private, it doesn’t have to tell anyone who its investors are. But when a company seeks to raise money from the public, in an IPO, the rules of disclosure get really strict. As an investor, you have the right to know who is selling. Most of the time, the shares of a company are being issued by the company itself. But in some cases, you’ll see selling by early investors — often venture capitalists — who want to cash out of the investment. If you see lots of insiders selling, that generally isn’t a good sign.

Underwriting

When you’re in school, you want to see your name on the perfect attendance list or maybe the dean’s list. But when you’re an investment banker, the goal is to be part of the underwriting list on as many IPOs as possible. When a company goes public, it must list all the investment banks and advisors that helped bring the shares to market. For big IPOs, the list can be a long one and is often a who’s who of investment banks.

Legal matters

If you want to get sued, one of the best ways to make it happen is to start a business. Companies of all sizes are constant targets of lawsuits, and young companies looking to go public are no exception. Most of these suits are nuisances or minor, but periodically outstanding litigation can be significant, especially if it pertains to the product or service being sold. This section of the prospectus must outline any pending suits against the company. The company itself usually gives a little bit of commentary on how significant it thinks the litigation is.

Supporting the IPO: Making success last

When IPOs fail, it makes investment bankers look bad. If shares of an IPO can’t stay above the offering price (the price at which the shares are sold to initial investors) it reflects poorly on the investment bankers. After all, if the shares were priced too high, that meant that the investors overpaid or the investment banker didn’t understand the business well enough. When a stock starts to trade on an exchange, such as the New York Stock Exchange, following the IPO that’s called aftermarket trading. If the price of the IPO, in aftermarket trading, falls below the offering price, it’s called a broken deal. Not good for investment bankers or investors.

And that’s why keeping a company on the right track, even after its IPO, is viewed as part of the responsibility of the investment banker. To be clear, the investment banker can’t do anything to change the way the company is being run — that’s up to the management team of the company. Still, there are levers that the investment bankers can pull to keep the IPO working for all parties, at least in the very short term.

Holding the insiders hostage with lockups

Just about the last thing IPO investors want to see is all sorts of selling by officers and directors the second after a company goes public. Think of it this way: Stock prices are set by supply and demand. If after a company goes public, employees and officers start dumping their stock, the market will be swamped with a supply of stock and push down the price of the shares. This unleashing of supply could create an avalanche of selling, not to mention spook investors by the strong negative signal it sends.

To prevent this downward spiral, investment bankers help companies create a lockup period (a set period of time during which the officers and directors are prohibited from selling shares). Lockup periods come in all types and can be customized by the company and its investment bankers.

Quiet periods

Regulators get a bit touchy when companies start looking to sell stock to the public for the first time. Securities regulations are in place to curb any activities that will fool investors into buying investments where the sellers know they’re a bust. Regulators and investment bankers work together to control the information that a company and its officers parse out to investors prior to an IPO and right after it’s done.

A company is prohibited from engaging in promotional activity to push up the value of its IPO, usually prior to the IPO and up to three months afterward. Investment bankers, too, must watch what they say and stick to the facts and not use promotion. It’s a fine line, for sure. After all, part of the IPO process includes roadshows (visits with potential investors). Talking about the IPO or the company is not illegal. In fact, it’s essential — full disclosure is the point of the IPO process. But the key is that the company and investment bankers can’t get promotional and make misleading promises about the company’s prospects.

Follow-on and secondary offerings

Raising money from the capital market can be like plastic surgery in Hollywood: Once someone gets started, it can be hard to stop. Similarly, once a company raises money from investors by selling stock to the public, that’s usually not the end of the process.

Companies, with the help of their investment bankers, can come back another time to raise money with a follow-on offering. During a follow-on offering, companies can sell additional shares to the public. These offerings can generate more capital for the company, which may help it turbocharge its growth. But in the process, the company is also creating new shares and selling them. And when the additional shares hit the market, they dilute the value of the existing shares, or make them worth less because the company is carved into more pieces. The underwriter is closely involved in these follow-on offerings.

Another time additional shares may go to market is in a secondary offering. Secondary offerings allow significant current investors to sell their shares in an organized fashion, after the IPO. Secondary offerings are not dilutive because no new shares are created. The shares existed before — they were just held by insiders. Insiders are simply selling shares they had before.

What are unicorns?

Some companies resist or put off selling shares to the public as long as possible. They might postpone an IPO because they don’t need the money, as they have patient investors not in a hurry to cash in. Some companies might prefer to stay private so they don’t have to worry about the requirements of being a public company. But for whatever reasons some companies stay private for a long time, a small few get very large. These companies, which generally see their valuations balloon to $1 billion or more, are so rare that they’re called unicorns. Just as you’re not likely to see a unicorn grazing in the fields, private companies able to hit valuations of $1 billion are rare, too. Yet, in 2019 investors spotted two unicorns: ride-sharing company Uber Technologies and corporate collaboration Slack. By the time they became public companies, Uber and Slack were worth $8.1 billion and $7.4 billion, respectively.

Seeing What Sell-Side Analysts Do

When companies decide to go public, there’s no shortage of investment bankers who are lining up to get the job. The fees associated with underwriting an IPO can be significant, so just about every investment banking firm would be happy to get the piece of the deal.

Because of the intense competition for deals to bring companies public, investment bankers often have to sweeten the pot and pitch all the support they can provide to the deal.

One way investment bankers allay this concern is by offering aftermarket research support. Most large investment banking operations employ teams of sell-side analysts who research companies, including many of the ones that the investment bank brought public, and produce reports to tell investors if the stock is worth a look.

The goals of the sell-side analyst

The sell-side analyst at a firm that does investment banking has a somewhat complicated job. Their primary job is to use fundamental analysis (the ability to determine the value of a company examining the details of the business) to help investors decide whether to invest. But here’s where things get complicated. Sell-side analysts are writing about companies that just so happen to be some of the investment bank’s best clients and generate large fee income from IPOs, mergers, or follow-on offerings.

Given the conflicts that sell-side analysts face, it’s important to understand the roles that these professionals serve, including the following:

-

Protecting new stocks from being lost and forgotten: When a company goes public, it’s suddenly in competition with thousands of other publicly traded companies. There are massive companies with huge market values, like Microsoft and Exxon Mobil, in addition to small and midsize companies. Investors have no shortage of choices when it comes to finding stocks to buy.

Reminding investors to take a look at a newly public company is one role of the sell-side analyst. By providing research coverage on a newly public company, the sell-side analyst is drawing attention to that stock. And having analyst coverage from a major Wall Street firm is a way for a company to avoid being an orphan (forgotten stock) with investors.

- Performing surveillance for investors: Pity the poor mutual fund manager. These buy-side investors need to scour Wall Street for the very best investments that will help them beat the market and justify the fees they charge their investors. But even for large mutual funds, with sizeable teams of analysts, doing in-depth research on every stock out there is virtually impossible. That’s why buy-side investors often look to the sell-side analysts for help. The sell-side analysts are laser focused on a somewhat limited universe of stocks. This specialization helps them establish an expertise in certain industries. Their research summarizes the risks and opportunities of a certain company, saving the buy-side investors lots of time and potential mistakes. Reports from sell-side analysts may highlight stocks that buy-side investors weren’t even following or aware of. Buy-side analysts rely mostly on their own research, but sell-side research might be something they would consider, too.

- Highlighting anomalies: Because sell-side analysts are so focused on certain companies, they’re able to pinpoint stocks that may be attractive, but overlooked, because other investors aren’t paying attention to the full story. Sell-side analysts can afford the time to really dig into a company and see, for instance, that revenue may have fallen not due to a problem with the business, but because it sold off a business unit.

What investors look to sell-side analysts for

Sell-side analysts are the line into the company for some investors. Sell-side analysts take the time to read the reports companies put out and listen into all the earnings conference calls, where the management teams discuss the performance of their company during the previous three months.

And for that reason, investors have some pretty high demands of their sell-side analysts, including the following:

- Research reports: The primary product from sell-side analysts is the research report. These reports (covered in more detail in the “Examining a Sample Research Report” section, later in this chapter) are where sell-side analysts spell out everything they know about the company and communicate their findings to investors.

- Instant updates: Following any big news from a company, investors expect sell-side analysts to be on top of the development. Instant updates are rapid dispatches from the sell-side analysts explaining what the takeaway from the new development is and whether it changes their opinion on the stock.

- Industry analysis: Although sell-side analysts primarily concern themselves with individual companies, most recognize the importance of industry factors. Many top sell-side analysts produce an industry analysis where they look at the larger forces at play in the industry and how they could affect companies within the industry.

Spreading the word: Disseminating sell-side research

Research doesn’t do anyone any good if it’s just sitting on an investor’s shelf. Getting the word out, and sharing research ideas, are how sell-side analysts get noticed. When sell-side analysts make a name for themselves, they often draw attention to their firms. Sometimes a sell-side analyst gets so well known in an industry that companies looking to go public look to the firm as an underwriter. It’s much how real-estate agents who focus on specific neighborhoods often win many of the listings in that area.

Investment banks get out the research from their sell-side analysts in a number of ways, including through the following:

- The broker network: Most of the large firms with investment banking operations — the Bank of Americas and Morgan Stanleys of the world — employ armies of brokers around the globe. These brokers provide investment help and guidance to clients. The brokers often refer to the research of sell-side analysts when making investment recommendations.

- Buy-side connections: Big mutual funds and other institutions tend to have ongoing relationships with certain large investment banks. It’s a tangled relationship with the buy-side investors looking to the investment banks as a source of all sorts of services, including trading and research. Big investment banks typically forward all their research to these large customers.

- Electronic distribution: As more individual investors try their hand at picking stocks themselves, there’s been increased demand for them to obtain sell-side research. Most of the large online brokerage firms, including TD Ameritrade and Charles Schwab, provide research reports from some of the big investment banking operations.

Examining a Sample Research Report

Research reports aren’t exactly the kinds of things you start reading and can’t put down. J. K. Rowling probably doesn’t worry much about competing with the latest research report on IBM from a major investment bank. That said, oodles of important information about a company can be stuffed into a research report. And knowing how to read research reports has elements of both art and science.

What to look for in the document

Research reports don’t have to follow a specific formula. Analysts at different investment banks have some latitude in determining the look and feel of their reports. But more often than not, research reports follow a certain protocol of what investors expect them to look like.

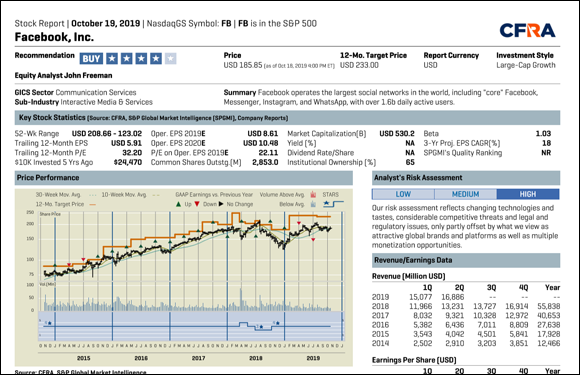

Many of the research reports from major research organizations follow somewhat of a pattern that contain key elements, making them easy for investors to find information they need. Figure 3-1 is a reprint of the first page of a research report from CFRA.

Courtesy of S&P Capital IQ

FIGURE 3-1: A page of a research report from CFRA.

The main sections of a research report

Investors are busy people. They don’t have the time to read through a research report that buries the findings and disguises the analysts’ decisions. Research reports are designed to be highly functional and percolate to the top the information that’s most important so investors can find it quickly.

Again, there’s no standard or required format for research reports to follow. But most of the time, they contain a number of key elements, including the following:

-

Recommendation: Analysts don’t hide how they feel about stocks. Right at the top of most research reports is the recommendation, typically a phrase that tells investors what the analysts think about buying the investment. Most analysts use one of the following terms: “strong buy,” “buy,” “hold,” “sell,” or “strong sell.”

Many beginning investors tend to place too much emphasis on the recommendation. Sure, it’s easy to just see if the analyst rates the stock a “strong buy” and then run out and buy it. But savvy investors know that most of the value of the research report is in the analysis of the company and the industry, and they don’t blindly follow the recommendation.

Many beginning investors tend to place too much emphasis on the recommendation. Sure, it’s easy to just see if the analyst rates the stock a “strong buy” and then run out and buy it. But savvy investors know that most of the value of the research report is in the analysis of the company and the industry, and they don’t blindly follow the recommendation. - Price target: If you visit a research analyst’s office, you may expect to find a crystal ball. Most analysts make a bold prediction of where they think the stock could be trading in the future, usually 12 months from the time of the report. The price target is usually derived using different techniques, some of which are covered later in this book, including discount cash-flow analysis.

- Key statistics: Buy-side analysts use research reports to save them time. Many investors are looking for quick, at-a-glance information to help them get a feel for a company’s future. The key statistics portion of a research report typically gives investors a summary of all the numerical data points that matter, ranging from the stock price to financial ratios such as price-to-earnings ratios. In this area of the report, you’ll also find the analyst’s forecast of the company’s future earnings, a key part of creating a price target.

- Highlights/summary: Research reports can get lengthy, sometimes spanning ten pages or even more if it contains in-depth information about the industry. The highlights or summary area attempts to boil all this information down to the bare essentials.

- Investment opinion: In the investment opinion area, the analyst gets some room to expound a bit on the rationale behind the recommendation. If the stock is a strong buy, the analyst makes a case for that recommendation in the investment opinion section.

- Business summary: Believe it or not, some investors just know companies by the trading symbol. In this part of the report, analysts usually show investors that the investment is backed by a company that generates profits and earnings. The business is summarized in this portion of the report so investors can understand the key drivers of the company.

- Ratio analysis and financials: One of the best ways for investors to really dig into a company to see if it’s a good investment is by using ratio analysis. Dozens of critical financial ratios help investors assess the value and trajectory of a company. You can find out how to calculate these ratios yourself in Chapter 8. But you can save yourself some trouble, too, because most analysts calculate many of the key ratios for you in this section.

- Industry outlook: One of the influences on the profitability of a company is the industry that it’s in. Stocks in the grocery-store industry, for instance, typically keep a small portion of revenue as profit, while technology companies that make software and Internet services tend to keep a much higher percentage of their revenue. This part of the research report explains the industry and goes into what bearing that line of business has for the company.

Ways to look beyond the “buy” or “sell”

Sell-side analysts working at firms that do investment banking sometimes get looked at somewhat suspiciously. There’s a concern, sometimes warranted, that the sell-side research analysts are being overly bullish on companies because they’re clients of the firm. And in the past, such wrongdoing has been found.

But ignoring the work of sell-side analysts, simply because of a risk of conflict is a mistake. Remember: Sell-side analysts have the time to really dig into a company. Most sell-side analysts also follow several companies in the industry so they can spot broad trends that have ramifications on short-term movements of the stocks.

-

Focusing on everything but the recommendation: Sure, it’s easy to just look at the front page of a report and scan for the buy or sell. But doing so leaves out much of the most valuable information sell-side analysts provide. Look at how the price target is arrived at. What assumptions is the analyst making? The thinking behind the recommendation is more valuable than the recommendation itself.

Sell-side analysts are often criticized for never meeting a company they didn’t like and have a “buy” rating on seemingly every company in existence. And it’s true that sell-side analysts traditionally rank many more companies as strong buys than strong sells. That’s just a natural bias of the industry that anyone working with the investment banking industry needs to keep in mind. Also, remember that sell-side analysts rarely call stocks a “sell.” With many analysts, hold is actually the euphemistic term for “sell.”

Sell-side analysts are often criticized for never meeting a company they didn’t like and have a “buy” rating on seemingly every company in existence. And it’s true that sell-side analysts traditionally rank many more companies as strong buys than strong sells. That’s just a natural bias of the industry that anyone working with the investment banking industry needs to keep in mind. Also, remember that sell-side analysts rarely call stocks a “sell.” With many analysts, hold is actually the euphemistic term for “sell.” - Not overlooking independent research: Although large Wall Street firms with giant investment banking operations dominate research, they’re not alone. There are firms, like CFRA and Morningstar, that generate research that aren’t connected with any investment banking. Compare the opinions of independent analysts with those of sell-side analysts to see where they differ.

- Concentrating on larger industry analysis reports: Many leading sell-side analysts periodically (sometimes once a year) put out monstrous reviews of an industry. These reports are usually the best work many analysts put out. Because the reports are broad, the analysts don’t have to be as mindful about potentially upsetting companies that happen to be big clients of the firm. These reports also give the analysts more freedom to share their insights about the business. And don’t overlook the research from boutique investment banking firms, which typically focus on a narrow number of industries. These firms can share profound insights about an industry you don’t want to miss.

One thing nobody wants to happen, and that includes companies and investment bankers, is for the IPO to break, or fall below the offering price. Companies worry that if they become just one of the thousands of stocks available for trading, they may get lost in the Wall Street shuffle.

One thing nobody wants to happen, and that includes companies and investment bankers, is for the IPO to break, or fall below the offering price. Companies worry that if they become just one of the thousands of stocks available for trading, they may get lost in the Wall Street shuffle.