Chapter Four

THE STRANGER

San Bernardino, California

She was a stranger to most people, including her own family. On December 2, 2015, a twenty-something young woman named Tashfeen Malik from Pakistan and her husband, Syed Farook, gunned down fourteen people and wounded others in one of the deadliest mass shootings in America. Masked in black, her face concealed, the girl from Pakistan assaulted my religion.

In the first hour of the attack, I wondered aloud if Malik would be hated less if she sported a painted leather jacket, low-rise jeans, and leather boots. If she had appeared more Western, rather than hidden from the public’s view, she might have been accepted as a Muslim woman. Interviews with Western women confirm that they perceive Muslim women draped in dark garb, including the covering of their eyes, as anonymous or nonexistent. One American woman said to me, “I can’t talk to her if I can’t see her as a person.”

I wanted to believe that Malik’s religion did not matter. Even when it did. I knew that Islam would come under attack again by those who did not understand it because a Muslim woman ruined the lives of innocent Americans and put Islam in the spotlight. Again.

I watched the news in horror. My phone began to ring. Emails poured in from journalists wanting to know: How can a Muslim woman do this? In a cracked voice, I responded, as I had for the past fifteen years, “This is not my religion.” I did not know what the Pakistani-born woman believed she would accomplish by killing Americans in the name of Islam, ISIS, and possibly her gender.

When the names and faces of the victims flashed across the television screen—representing families who had lost a father, mother, brother, sister, child, or friend—I began to wonder if Malik fit into my simple Three Cs model. The first C had to do with context. Were there contextual clues, such as exposure to trauma, violence, or abuse, or did she have feelings of rage, anxiety, or depression that might explain her behavior? We can’t assume that Malik exhibited emotional problems, though she did alienate herself from the community to which she belonged. That no one knew who she really was made her a stranger among friends and family.

The second C focused on culture: the customs, traditions, and religious ideology that affect an individual’s childhood and his or her relations with the family and the community. Was Malik a victim or a champion (or protector or defender) of her culture? I knew from travels to Pakistan that most extremist men do not choose women to kill, but rather, women play a secondary role, which meant the cultural piece did not make sense. The third C explored an individual’s capability, which included the willingness to support or participate in extreme violence. In this case, Malik proved herself capable. But how and when she trained to use a weapon, and by whom, is still a mystery. According to public reports, all we know is that Malik knew how to kill in cold blood and may have had practice with target shooting.

Once again, I was compelled to speak for Islam and against violence in the name of my religion. After Malik’s attack, I received calls from the media. I told MSNBC and the Associated Press that Islam is a religion of mercy, peace, and compassion. That no pious, practicing Muslim would gun down innocent people. That killing is sinful, senseless, and Satanic. That the Quran made it explicitly clear that whoever saves a life saves all of humanity. That the Prophet of Islam once said that the gates of Heaven will be forever closed to one who takes a life in a suicide mission. However, extremists like Malik practiced Islam selectively and referenced religious verse out of context to suit their deadly actions.

In truth, Malik’s case is not as bizarre as it seems. There is a history of women in violent groups. I told MSNBC that what surprised me was that Malik assumed an operational role, which was uncommon for most extremist women. Many radical women are supporters, sympathizers: they help their men evade arrests, they keep their secrets, they feed their accomplices, they raise their children to become extremists, and much more. But so few actually learn how to kill, as Malik did, which raises questions: Where did she receive weapons training? Who trained her? Was there anyone else, aside from her husband, who had radicalized her? When had she become an extremist—before or after she arrived at Los Angeles International Airport?

Days later, security personnel announced on television that Malik had been radicalized for years. “This attack was planned for two years. . . . [Malik came from] a network from Pakistan.” “Yes, that’s plausible,” I told a Canadian reporter, when she asked me about the Islamic school that Malik had attended.

Soon enough, reporters suggested that Malik—like many other radicalized women—had led a normal life before she became a terrorist. This isn’t so unusual, either. No woman (or man) enters extremism without motive. However, in Malik’s case, investigators in December 2016, a year after the attack, were still clueless as to how she had turned violent.

Why now? The simple answer is that it’s complicated and complex. No two terrorists are alike, although there are patterns and trends that can explain, in part, why religious extremism is increasing. And there is a list of likely motivations that terrorism experts use as a guide to understand the reasons why ordinary Muslims are radicalized and commit the most extraordinary attacks. To be fair, religious-based violence is an old phenomenon that dates back to early Islamic history; some scholars cite the killing of Ali, a cousin and son-in-law of Prophet Muhammad, by another Muslim as the first “terror” attack. Other significant deaths of pious Muslims occurred after Muhammad’s death—his two grandsons, Hussein and Hassan, were both brutally slaughtered at the order of a man named Mawiya, who ruled a stretch of land that later became Syria. Rulers justified violence in the name of Islam, though there was no justification for it in the Quran. The leaders were simply motivated by greed and power.

Later that December day, Mama called to express her shock and sorrow. “It’s terrible,” she said. “Can you believe she was from Punjab?”

“Yes, I know; Punjabi women are anything but radical.” A frequent traveler to Pakistan, I know that Punjabi women in cities and major towns are known to be progressive and liberal-minded. They are politicians, peacemakers, playwrights, pilots, police officers, poets, and more. In my own family, I have women who are star-crazed fashion designers, successful entrepreneurs, and award-winning educators.

They are anything but mass murderers.

As a lecturer and researcher, I have learned that the radicalization process is devoid of categories or a step-by-step process. There is no how-to guide or “aha” moment. Nor is there a one-size-fits-all model. Which is why it’s useless and unnecessary to place violent women in classification boxes and create profiles. It doesn’t work. Instead, each woman’s entry into a terrorist group is unique because no two Muslim women are alike.1

The threat of women wishing to die for a cause is real. Decades of female participation on the front lines of terror have proved that women can be deadly. Women are determined and devoted to a cause they volunteer for or have been recruited into by male handlers. These women are young and old, secular and religious, married and single, or widows. Even mothers are motivated by a message of resistance, rebellion, and revenge. These women belong to a larger network of extremists who stress the need for justice, a narrative that resonates for women. According to Dr. Post, women usually radicalize for “altruistic” reasons: they express a desire to fight social injustice, some leave behind their own children to save future generations from real or perceived aggression, and many believe that violence is the only way to save the Muslim world.

Malik was the perfect stranger. She was no different than other Muslim women who slipped by intelligence and law enforcement officers when they entered America. I am reminded of the Pakistani woman Aafia Siddiqui, who made the FBI’s Most Wanted List for her relationship to senior terrorists including Khalid Shaykh Muhammad, who was a high-value target captured in a safe house in Pakistan and indicted on countless terrorism charges.

For years, Aafia Siddiqui did not concern us. When she studied at MIT in Boston, Siddiqui became an ardent supporter of wars in the Islamic world, including Bosnia, Chechnya, and Afghanistan. She rallied for innocent Muslims killed in the line of fire and vocally attacked countries for attacking Muslim lands. Years later, she was captured in Pakistan, where she allegedly disappeared until she suddenly showed up in Afghanistan and was arrested for attacking US military officers. Siddiqui was tried in New York for the alleged crime and then sent to serve her life sentence in Texas.

In Pakistan, thousands of people protested Siddiqui’s arrest and trial in America. For many, she was a heroine of Islam, and her supporters, including her own family, believed that she had been misjudged and mislabeled a terrorist. Pakistanis do not nurture the same feelings for Malik, whose barbaric act shamed the country from which she came.

In truth, Siddiqui was not the first Muslim woman who called on men to defend the rights of Muslims, though her case is highly controversial. Her sympathizers and family members believe that she didn’t join al-Qaeda willingly, and if she did, it was fate. Others insist that Siddiqui is a hardened terrorist and more dangerous than men—that she has the ability to deceive local and foreign authorities and disguise her intention to support and commit acts of violence. To this day, protesters organize outside the prison in Texas where Siddiqui is held and demand her release, according to an American security officer whom I met at a law enforcement event. If there’s one thing I have learned from Siddiqui’s case, it is that Muslim women continue to be perceived as victims of conflict rather than victimizers. Despite Siddiqui’s links with senior al-Qaeda operatives, many consider her to be a martyr—the ultimate sufferer—in the war on terrorism.

However, history offers evidence of women on the front lines of war. During the Afghan jihad, women supported their men with logistics and facilitation. I know this from dozens of articles I collected with my father, a linguist and translator. We surfed through Urdu-language magazine articles, some written by women, many written for women, on their role in jihad. In one editorial, a woman said, “We stand shoulder to shoulder with our men, supporting them, helping them . . . we educate their sons and we prepare ourselves . . . we march in the path of jihad for the sake of Allah, and our goal is Shahada [martyrdom].” Years later, women clad in all-black robes with matching gloves, their faces shielded by cloth, protested with banners on the streets of Islamabad, Pakistan’s capital city, and claimed their right to take over the city with violence. A local newspaper, the Daily Times, reported that the women justified their action against “those who are against Islam” because they were an “oppressed community.”

In Pakistan, male extremists and their leaders often manipulate women to win political attention and public sympathy. Their defiance of and disgust for the United States–led war on terrorism is a win-win: some men use this narrative to appeal to women who have little access to education and opportunities. In a personal interview with a former minister of information and the editor of a major newspaper, I was told that these women “are docile and under the subjugation of men; they are exploited by the maulvis [religious leaders] to challenge authorities [the state] and create fear.”

To be fair, the majority of mosques and religious schools in Pakistan do not incite violence or terrorism. A Muslim country, Pakistan has a history of secular politics—religious parties have never gained the majority of the vote in elections, nor do they have wide support across a moderate Muslim population. However, it is entirely possible that the San Bernardino shooter was radicalized in Pakistan by violent extremist groups before she entered the United States.

During the Malik investigation, I was asked about the Al-Huda University in Islamabad, run by a woman, Farhat Hashmi, who was educated in Scotland and earned her doctoral degree in Islamic studies at the University of Glasgow. When she returned to Pakistan, she founded Al-Huda to teach girls the meaning of the Quran. Her teachings are considered stringent. With nearly seventy schools across Pakistan, Hashmi is spreading a conservative ideology that secularists, liberals, and moderate Muslims perceive to be controversial and a viewpoint that restricts the rights of women and girls in Islam. In an interview with CBC News, I told a reporter, “When you learn about religion from a narrow lens . . . then you tend to have a less tolerant view of the world.” Before she committed mass murder, Malik attended the Al-Huda branch in the city of Multan in Pakistan while she studied pharmacology at a local university, a course she never completed.

The rigid teachings of Islam are all too familiar. Although Malik is the first Pakistani woman to shoot Americans, she represents a wider and more disturbing trend of an uncompromising Islamic scholarship spreading in the Muslim and Western worlds. The students of Al-Huda reminded me of the girls I met years ago at the largest girls’ madrasa, or religious seminary, in Quetta, the home of one-eyed Mullah Omar, the Taliban’s revered founder. There, I sat cross-legged on a rug talking to teachers who had all joined the school at the age of eight. In a short piece published in the travel section of the Washington Post, I wrote, “Behind the iron gates, girls as young as eight memorized the Quran; they also mended clothes and cooked their own food. ‘Don’t you want to see life outside of the school?’ I asked a young teacher. Her response still stings me. ‘Of course we have desires, but we learn to suppress them.’ ”2

My sharpest memory of that place was a young bright-eyed girl who sang religious songs. In ultraconservative Islam, it is forbidden to appear in front of unknown men, much less perform for them. But in the Quetta madrasa, the girl was honored for praising God’s name. Even so, I often wondered how the girls of the school felt about being confined within the walls of the madrasa. Did they want to go shopping? Or eat in a restaurant? Did they want to go to a secular/public school? Or just ride a bicycle outside? I was struck by the girls’ complacency, mistaken for gratitude they felt for their male leader.

One wintry afternoon, as we huddled together on the floor, I tried to teach the girls Islam. I told them the story of the Prophet’s first love, a woman named Khadija, who was fifteen years older, a successful businesswoman, and a widow. I referenced Islamic scripture to show the girls that they had the right to be free, think, and act of their own will.

“We have each other,” a seventeen-year-old teacher said to me in private, referring to the other girls, whom she considered her friends. And then I understood that an ultraconservative teaching of Islam was what allowed the girls to leave their homes. It meant something to them. Until they joined the madrasa, most of the girls had lived in seclusion—they were illiterate and ignorant of faith. As I smiled back at them, I began to understand how easy it is to accept a narrow version of religion as an opening to a new life while being oblivious to Islam’s truth. These girls had no clue that Islam afforded them the right to study, work, go to a movie, sing or dance (with other girls), and fall in love.

Behind the stone-gray walls, the girls looked happy. They had each other. A teacher with rosy cheeks and swan-white skin told me she would rather stay in the madrasa than return home for the holidays. I imagine that if I had been raised in their village and culture, I might have chosen to stay in the madrasa too, and rejoice in the company of friends rather than have to return to a patronizing father.

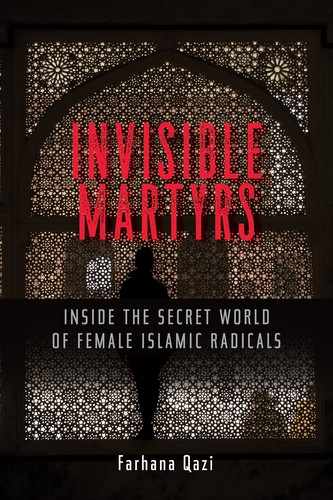

![]()

In the early days of Islam, Muslim women helped their men to victory. They tended to wounded soldiers. They carried messages and money. They called on men to fight to protect Muhammad. They were the mothers of the believers.3 Women were skilled in warfare. They were given swords to use in fighting by the early Muslim men. One of the most celebrated female fighters was Nusybah bint Ka’ab, also known as Umm Umarah (“mother of Umarah”). She fought in Islam’s second Battle of Uhud in 625 CE, lost one arm, and suffered eleven wounds as she protected her Prophet.4 After Muhammad’s death, Muslim women continued to fight. A Bedouin woman, Khawlah bint al-Azwar, dressed like a knight and entered the battlefield with other women. She “slashed the head of the Greek,” a reference to the Byzantines who retreated after Muslims declared victory.5

In the spirit of faith, the first mujahidaat, or female fighters, were elevated by the Prophet as the most noble of women. Only those who sacrificed their lives in defense of their honor, their homes, or Prophet Muhammad would be remembered. These women were entitled to Heaven for their contribution in war. They were celebrated as martyrs of the faith. Under Islamic law, Malik could not qualify as a martyr because she had killed innocent people, for which there is no passage to Paradise.

Despite her narrow lens on the world, Malik didn’t seem out of the ordinary to anyone, although there should have been behavioral clues to alert the community and the police. In Malik’s case, Muslims at the mosque didn’t know her. Her own brother-in-law professed on national television that he had never seen her face. For an American, this seems absurd. I have told reporters that even in strict Islamic households, women let down their hair and show their face to male relatives. How could a woman living in our neighborhoods not socialize with her family members, much less other Americans?

Ultraconservative Islam is not uncommon in the United States. In many Muslim families living in the West, a girl is expected to marry young and start her own family. I am familiar with many girls who lead parallel lives in America; living in ultraconservative families, they struggle to fit in, and few adjust to the values in the dominant culture in which they are raised. I know a sixteen-year-old girl who is not allowed to leave the house without being accompanied by one of her parents or brother. She wears the niqab, a full-length veil that covers her body and her face, everything except her eyes. She is home-schooled, and her parents are looking for a groom as I write this, which means she will probably get married before she is twenty, like her elder sister, who had an arranged marriage. It’s also likely that a teenage girl in Virginia will do exactly as she is told, obeying fixed gender norms set by her parents, who follow one narrow version of Islam. Although this young girl is not an extremist, her restricted life and narrow worldview make her a vulnerable target.

In addition to the crimes she committed, Malik also reinforced the traditional sexual stereotype of a Muslim woman as a home-bound housewife, who is likely oppressed and ostracized from the world. To the American public, she looked like the orthodox Muslim woman devoid of freedom. Nothing could be further from the truth, as Malik proved to be an equal accomplice with her terrorist husband.

Will there be another Malik? My answer is “I hope not,” though I can’t be sure, when extremist women, like men, live among us. Reporting radicals to authorities is an important first step toward keeping America safe. In the fight against violent extremism, numerous American Muslims have reported suspicious activities to law enforcement officers to disrupt attacks against the home-land. Ron Haddad, the chief of police for Dearborn, Michigan— often referred to as the “Arab capital of North America,” with its swelling population of Arab Muslims—acknowledges the help he has received from Muslims.

In an effort to improve community policing and relations with the American Muslim community, the FBI started a program called “Shared Responsibility Committees” in November 2015. The purpose of these committees was to bring together law enforcement officers, mental health professionals, social workers, and imams and other religious leaders to create meaningful and effective intervention strategies. The program was controversial, as such a high level of engagement with local Muslim communities to fight terrorism in the United States is unprecedented. Other efforts by the federal government were also geared toward reducing the number of alienated Muslim youth drawn to ISIS and other terrorist groups through extremist propaganda and offline networks.

In 2016, I met with Hedieh Mirahmadi, a Muslim activist and lawyer based in Montgomery County, Maryland, who supports the FBI’s outreach efforts to engage the Muslim youth before it’s too late. Of Iranian descent, born in Chicago and raised in Los Angeles, Mirahmadi moved to the Washington, DC, area in 1997 and founded WORDE, a nongovernmental organization committed to empowering the community with educational tools and resources to fight against extremists at home and abroad.

I first met Mirahmadi when I was a young government analyst, and we reconnected years later at a conference on radical women, held at the Center for Strategic International Studies. She invited me to her home, a palatial space with a majestic Quran and antique furniture, and talked about her work over tea and a fruit tart.

“I had a series of pivotal events,” she recalled. “I came across what I considered to be nefarious groups that didn’t have the best interests of America at heart, and not the best interests of Muslims at heart. The 1990s was a time when some people had an anti-pluralistic and anti-American approach to Islam that concerned me. It almost led me to leave Islam. So I found a different group of people very much tied to Sufism, but my concern and passion about this issue . . . never went away. I spent countless hours interviewing young Muslims trying to understand what was drawing them to go and fight in faraway lands. So many felt that there was a struggle for the soul of Islam, and it was very pronounced in America.”

Like Mirahmadi, I remember growing up in the 1990s. Conflicts in the Muslim world continued to shape the way American Muslims reacted. The long, drawn-out war in Afghanistan with the Soviet Union had just come to an end, sparking the rise of violent extremists that would spill into Pakistan. We both agreed that the threat, twenty years later, was the same but the dynamics had changed.

“Are you concerned about extremism in America?” I asked her; this was a few months before Tashfeen Malik terrorized the San Bernardino community.

“The recruitment patterns have changed,” she replied. “It’s not in person and not in the mosque. Today, it’s in third spaces, and groups have changed; they are not calling everyone to go to war overseas.”

Which is why ISIS recruits women like Malik. They are looking for local Muslims to conduct local attacks, similar to the sequence of attacks that are taking place in European cities, I thought.

“All those things have changed,” she continued, “but the fundamental issue that remains is how do you build resilience of communities against that? American Muslims need a version of their religion that is not incompatible with being American. The message that terrorism has no place in Islam resonates, and now American Muslims are more courageous to condemn the violence. The message that American Muslims can be loyal citizens to this country and violent extremists are deviants of mainstream Islamic practice is finally being heard, but there is still work to be done.”

Under her guidance, WORDE is creating the space for local communities to become active participants in public safety. Since 2008, the organization has provided training to thousands of community members, including other faith-based leaders and members, to encourage inclusion, tolerance, and awareness of the dangers of violent extremism.

“Our goal is to build awareness by helping the community look at risk factors and potential drivers of violence,” she said. “The key factors are psychological, sociological, economic, and ideological beliefs.”

The matrix sounded familiar. Borrowing from other models, Mirahmadi understands that there are no profiles, but there are factors to help identify at-risk individuals, similar to those used for school shooters and gang members. Community members, including religious leaders, counselors, social workers, educators, and parents, use the matrix to help them engage with potential recruits before calling the police.

But for Malik and the San Bernardino community, there was no intervention and nothing to report, because Malik shielded herself from the mosque and the mainstream community—even when she went to the mosque, she prayed and returned home. People like Malik are an anomaly, a rare radical who attempts an attack and succeeds. To prevent another operative like Malik from attacking the United States, the community will need to be more vigilant. Though the Muslim community cannot keep an operative from entering the United States, which is the responsibility of law enforcement and immigration authorities, it is fair to expect the larger community to know its neighbors. I am reminded of the words of a young imam, who said to me, “We need to clean our own homes and strengthen our families.”

We can no longer live by not knowing the stranger next door.