CHAPTER 21

Domestic Production Activities Deduction

How often does Uncle Sam reward taxpayers for simply doing a good job? There is a special deduction designed to encourage domestic production activities. Also referred to as the “manufacturer's deduction,” this write-off effectively slashes the tax rate applied to such activities and does not require any additional cash outlay to qualify.

There have been suggestions to eliminate this deduction entirely, as part of overall tax reform. To date, there have been no formal proposals, but stay alert for possible developments.

Background

In the past, there were 2 special tax regimes designed to assist U.S. companies doing business abroad: the domestic international sales corporation (DISC) and the Extraterritorial Income Exclusion Act. The World Trade Organization viewed these regimes as discriminatory in favor of U.S. companies, and the European Union was authorized to impose sanctions on U.S. goods. In response, these regimes have been replaced by a deduction for domestic production activities. The deduction does not require any foreign distribution of goods or services; it is based on producing things within the United States.

Qualified Producers

Only “qualified producers” can claim the deduction. The term is not limited to traditional manufacturers in the United States. It applies to a business that engages in any of the following activities:

Selling, leasing, or licensing items manufactured, produced, grown, or extracted in the United States in whole or significant part (see safe harbor discussed later). One district court said that creating gift baskets by putting together candy, cheese, wine, crackers, and such made by others was a qualified activity for which sales could be taken into account in figuring the domestic production activities deduction.

Selling, leasing, or licensing films (other than sexually explicit productions) produced in the United States (50% or more of compensation relating to production relates to services of actors, directors, producers, and service personnel performed in the United States). Gross receipts from the distribution of multiple channels of video programming are not domestic production gross receipts.

Construction in the United States includes both erection and substantial renovation of residential and commercial buildings. While there is no IRS guidance on what constitutes a substantial renovation, it can be assumed to be any cost that would be required to be capitalized (as opposed to a currently deductible repair).

Engineering and architectural services relating to a construction project performed in the United States.

Software developed in the United States, regardless of whether it is purchased off-the-shelf or downloaded from the Internet. The term “software” includes video games. But, with some de minimis exceptions, the term does not include fees for online use of software, fees for customer support, and fees for playing computer games online. The IRS says that an app that allows customers to download a fee schedule is online software that is not being disposed of (i.e., does not qualify for the domestic production activities deduction).

While it could be argued that every business produces something, not every business is treated as a qualified producer. Businesses engaged in the following activities are specifically not qualified producers:

Cosmetic activities related to construction, such as painting.

Leasing or licensing to a related party.

The sale of food or beverages prepared at a retail establishment. However, if a business both manufactures food and sells it at a restaurant or take-out store, income and expenses can be allocated so that those related to manufacturing and wholesale distribution qualify for the deduction. Thus, in the so-called Starbucks situation, roasting and packaging coffee beans could qualify, but selling the beans or brewed coffee at stores would not.

Safe Harbor

The deduction is limited to activities that are in whole or “in significant part” in the United States. Under a safe harbor, labor and overhead costs incurred in the United States for the manufacture, production, growth, and extraction of the property are at least 20% of the total cost of goods sold of the property.

Even if you fail to meet this safe harbor, you can still demonstrate that the activity is “in significant part” a U.S. activity based on all the facts and circumstances.

Figuring the Deduction

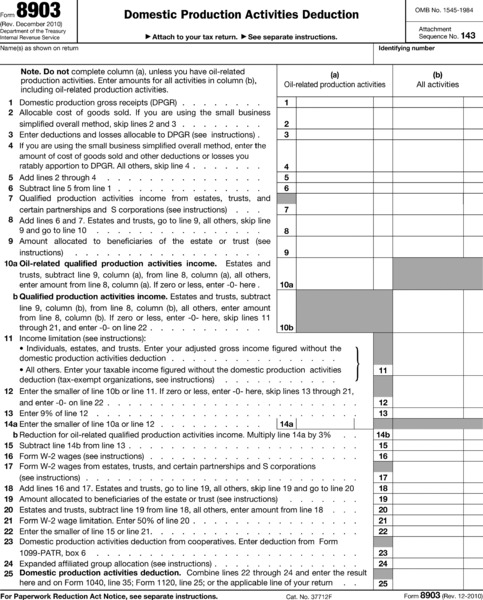

The deduction is 9% of income from domestic production activities and is figured on Form 8903, Domestic Production Activities Deduction (Figure 21.1). This results in an effective top tax rate on corporations of 32% (instead of the maximum 35% rate). “Income” means gross receipts reduced by certain expenses. Note that special computation rules come into play for short tax years and when a company acquires or disposes of a major portion of the business (including a unit of the business) during the year (explained in temporary and proposed regulations issued on August 27, 2015).

Figure 21.1 Form 8903, Domestic Production Activities Deduction

Allocable Gross Receipts

Start with gross receipts from qualified domestic production activities, called domestic production gross receipts (DPGR). If your business is entirely domestic, then all gross receipts are taken into account. If you have both domestic and foreign activities, use any reasonable method to allocate gross receipts to qualified domestic activities.

Proposed regulations clarify the meaning of DPGR. Previously, the IRS had used a benefits and burdens of ownership test to identify whether a taxpayer could claim the deduction for contracted manufacturing activities; this test is not used in the proposed regulations.

Under a de minimis rule, if less than 5% of total gross receipts are derived from nonqualified domestic production activities, you do not have to make any allocation; all gross receipts are treated as attributable to qualified domestic production activities.

If there is a service element in the activity, allocate gross receipts between the qualified activity and the services. However, no allocation is required if the gross receipts relate to a qualified warranty and other gross receipts from these services are 5% or less of the gross receipts from the property.

Qualified production activity income (QPAI) is determined on an item-by-item basis. An “item” is something offered for sale to customers; it produces income from the lease, rental, license, sale, exchange, or other disposition of property manufactured, produced, grown, or extracted in whole or significant part in the United States. Also qualifying are domestic films, construction, and engineering and architectural services.

QPAI is taken into account for purposes of this computation under your usual method of accounting (e.g., cash or accrual basis).

Allocable Cost of Goods Sold and Related Expenses

Next, reduce these gross receipts by the cost of goods sold and related expenses. Related expenses include direct costs of production, plus a portion of indirect expenses. The allocation is based on your books and records if possible, or if not, on any reasonable method.

There are three ways to allocate expenses to domestic production gross receipts:

Small business simplified overall method. Total cost of goods sold and other deductions are apportioned ratably between DPGR and non-DPGR based on relative gross receipts. This method is the easiest to compute, although it may not produce the most favorable allocation. This method can be used only if average annual gross receipts are no more than $5 million, or the taxpayer is eligible to use the cash method of accounting.

Design and development costs, including packaging, labeling, and minor assembly operations, are not taken into account in determining manufacturing or production activities.

The deduction applies for both regular and alternative minimum tax purposes, so claiming it will not trigger or increase AMT liability.

Limitations on the Deduction

The deduction is subject to 2 limitations:

It cannot exceed taxable income (for C corporations) or adjusted gross income for sole proprietors and owners of partnerships, limited liability companies, or S corporations. Thus, it cannot be used to create a net operating loss.

It cannot exceed 50% of W-2 wages. W-2 wages include both taxable compensation and elective deferrals (e.g., employee contributions to 401(k) plans).

All W-2 wages used to determine the wage limitation on the domestic production activities deduction must be allocated to the business's DPGR. Temporary regulations provide guidance on figuring the amount of wages taken into account for a short taxable year. A short taxable year may occur, for example, when a business is acquired or disposed of.

For pass-through entities, allocated W-2 wages are no longer limited to a percentage of the business's allocated QPAI. Thus, the wage limitation is 50% of the wages that the business deducts in figuring its QPAI. There are 3 methods provided for determining W-2 income, called “(e)(1) wages” under Treasury regulations. One method looks to the lesser of Box 1 or Box 5 of Form W-2, while the other alternatives are more complex.

W-2 wages do not include payments to independent contractors, self-employment income, or guaranteed payments to partners.

For exporters, there is another limitation related to the phase-out of the tax rate on extraterritorial income (ETI). But some businesses that are exporters may be able to qualify for both benefits.

This deduction cannot be used to create or increase a net operating loss.

Pass-Through Entities

The deduction is applied at the owner (not entity) level. This means that the business must allocate gross receipts, cost of goods sold, and related expenses from qualified production activities to the owners so they can claim the deduction on their personal returns.

A special allocation rule applies for purposes of the limitation to 50% of W-2 wages. The allocation of this amount is the lower of the owner's allocable share of wages or 2 times 9% of production activities income for 2016.

Self-Employed

The domestic production activities deduction is figured on Form 8903, Domestic Production Activities Deduction.

The deduction is then entered in the “Adjusted Gross Income” section of Form 1040. It is not a business deduction reported on Schedule C.

Partnerships and LLCs

The domestic production activities deduction is figured on Form 8903, Domestic Production Activities Deduction. However, the partnership or LLC does not claim the deduction; it is a pass-through item.

The information necessary to enable owners to figure their shares of this deduction is reported to them on line 13 of Schedule K-1 (Codes “T,” “U,” and “V”). Owners then figure the deduction, applying their own adjusted gross income limitation, and enter the deduction in the “Adjusted Gross Income” section of Form 1040.

S Corporations

The domestic production activities deduction is figured on Form 8903, Domestic Production Activities Deduction. However, the corporation does not claim the deduction; it is a pass-through item.

The information necessary to enable owners to figure their share of this deduction is reported to them on line 12 of Schedule K-1 (Codes “P,” “Q,” and “R”). Owners then figure the deduction, applying their own adjusted gross income limitation, and enter the deduction in the “Adjusted Gross Income” section of Form 1040.

C Corporations

The domestic production activities deduction is figured on Form 8903, Domestic Production Activities Deduction, and entered on Form 1120.