CHAPTER 1

Business Organization

- Sole Proprietorships

- Partnerships and Limited Liability Companies

- S Corporations and Their Shareholder-Employees

- C Corporations and Their Shareholder-Employees

- Employees

- Factors in Choosing Your Form of Business Organization

- Forms of Business Organization Compared

- Changing Your Form of Business

- Tax Identification Number

If you have a great idea for a product or a business and are eager to get started, do not let your enthusiasm be the reason you get off on the wrong foot. Take a while to consider how you will organize your business. The form of organization your business takes controls how income and deductions are reported to the government on a tax return. Sometimes you have a choice of the type of business organization; other times circumstances limit your choice. If you have not yet set up your business and do have a choice, this discussion will influence your decision on business organization. If you have already set up your business, you may want to consider changing to another form of organization.

According to the Tax Foundation, 94% of all businesses in the United States are organized as sole proprietorships, partnerships, limited liability companies (LLCs), or S corporations, all of which are “pass-through” entities. This means that the owners, rather than the businesses, pay tax on business income. Nearly 50% of the private sector workforce is employed by these pass-through entities. The way in which you set up your business impacts the effective tax rate you pay on your profits (after factoring income taxes and employment taxes). Taxes, however, are only one factor in deciding what type of entity to use for your business.

As you organize your business, consider which type of entity to use after factoring in taxes (federal and state) and other consequences. Also consider whether to change from your current form of business entity to a new one and what it means from a tax perspective. Finally, be sure to obtain your business's federal tax identity number (or a new one when making certain entity changes).

For a further discussion on worker classification, see IRS Publication 15-A, Employer's Supplemental Tax Guide.

Sole Proprietorships

If you go into business for yourself and do not have any partners (with the exception of a spouse, as explained shortly), you are considered a sole proprietor, and your business is called a sole proprietorship. You may think that the term proprietor connotes a storekeeper. For purposes of tax treatment, however, proprietor means any unincorporated business owned entirely by one person. Thus, the category includes individuals in professional practice, such as doctors, lawyers, accountants, and architects. Those who are experts in an area, such as engineering, public relations, or computers, may set up their own consulting businesses and fall under the category of sole proprietor. The designation also applies to independent contractors. Other terms used for sole proprietors include freelancers, solopreneurs, and consultants. And it includes “dependent contractors”: self-employed individuals who provide all (or substantially all) of their services for one company (often someone laid off from a corporate job who is then engaged to provide non-employee services for the same corporation). Further, it includes those working in the “gig economy” for such companies as Uber, Lyft, and TaskRabbit.

Sole proprietorships are the most common form of business. The IRS reports that one in 6 Form 1040s contains a Schedule C or C-EZ (the forms used by sole proprietorships). Most sideline businesses are run as sole proprietorships, and many start-ups commence in this business form.

There are no formalities required to become a sole proprietor; you simply conduct business. You may have to register your business with your city, town, or county government by filing a simple form stating that you are doing business as the “Quality Dry Cleaners” or some other business name other than your own (a fictitious business name, or FBN). This is sometimes referred to as a DBA, which stands for “doing business as.”

From a legal standpoint, as a sole proprietor, you are personally liable for any debts your business incurs. For example, if you borrow money and default on a loan, the lender can look not only to your business equipment and other business property but also to your personal stocks, bonds, and other property. Some states may give your house homestead protection; state or federal law may protect your pensions and even Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs). Your only protection for your personal assets is adequate insurance against accidents for your business and other liabilities and paying your debts in full.

Simplicity is the advantage to this form of business. This form of business is commonly used for sideline ventures, as evidenced by the fact that half of all sole proprietors earn salaries and wages along with their business income. For 2013 (the most recent year for statistics), more than 24.1 million taxpayers filed returns as sole proprietors.

Independent Contractors

One type of sole proprietor is the independent contractor. To illustrate, suppose you used to work for Corporation X. You have retired, but X gives you a consulting contract under which you provide occasional services to X. In your retirement, you decide to provide consulting services not only to X, but to other customers as well. You are now a consultant. You are an independent contractor to each of the companies for which you provide services. Similarly, you have a full-time job but earn extra money by performing chores for customers through TaskRabbit. Here too you are an independent contractor.

More precisely, an independent contractor is an individual who provides services to others outside an employment context. The providing of services becomes a business, an independent calling. In terms of claiming business deductions, classification as an independent contractor is generally more favorable than classification as an employee. (See “Tax Treatment of Income and Deductions in General,” later in this chapter.) Therefore, many individuals whose employment status is not clear may wish to claim independent contractor status. Also, from the employer's perspective, hiring independent contractors is more favorable because the employer is not liable for employment taxes and need not provide employee benefits. (It costs about 30% more for an employee than an independent contractor after factoring in employment taxes, insurance, and benefits.) Federal employment taxes include Social Security and Medicare taxes under the Federal Insurance Contribution Act (FICA) as well as unemployment taxes under the Federal Unemployment Tax Act (FUTA).

You should be aware that the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) aggressively tries to reclassify workers as employees in order to collect employment taxes from employers. A discussion about worker classification can be found in Chapter 7.

There is a distinction that needs to be made between the classification of a worker for income tax purposes and the classification of a worker for employment tax purposes. By statute, certain employees are treated as independent contractors for employment taxes even though they continue to be treated as employees for income taxes. Other employees are treated as employees for employment taxes even though they are independent contractors for income taxes.

There are 2 categories of employees that are, by statute, treated as non-employees for purposes of federal employment taxes. These 2 categories are real estate salespersons and direct sellers of consumer goods. These employees are considered independent contractors (the ramifications of which are discussed later in this chapter). Such workers are deemed independent contractors if at least 90% of the employees’ compensation is determined by their output. In other words, they are independent contractors if they are paid by commission and not a fixed salary. They must also perform their services under a written contract that specifies they will not be treated as employees for federal employment tax purposes.

Statutory Employees

Some individuals who consider themselves to be in business for themselves—reporting their income and expenses as sole proprietors—may still be treated as employees for purposes of employment taxes. As such, Social Security and Medicare taxes are withheld from their compensation. These individuals include:

Corporate officers

Agent-drivers or commission-drivers engaged in the distribution of meat products, bakery products, produce, beverages other than milk, laundry, or dry-cleaning services

Full-time life insurance salespersons

Homeworkers who personally perform services according to specifications provided by the service recipient

Traveling or city salespersons engaged on a full-time basis in the solicitation of orders from wholesalers, retailers, contractors, or operators of hotels, restaurants, or other similar businesses

Full-time life insurance salespersons, homeworkers, and traveling or city salespersons are exempt from FICA if they have made a substantial investment in the facilities used in connection with the performance of services.

Day Traders

Traders in securities may be viewed as being engaged in a trade or business in securities if they seek profit from daily market movements in the prices of securities (rather than from dividends, interest, and long-term appreciation) and these activities are substantial, continuous, and regular. Calling yourself a day trader does not make it so; your activities must speak for themselves.

Being a trader means you report your trading expenses on Schedule C, such as subscriptions to publications and online services used in this securities business. Investment interest can be reported on Schedule C (it is not subject to the net investment income limitation that otherwise applies to individuals).

Being a trader means income is reported in a unique way—income from trading is not reported on Schedule C. Gains and losses are reported on Schedule D unless you make a mark-to-market election. If so, then income and losses are reported on Form 4797. The mark-to-market election is explained in Chapter 2.

Gains and losses from trading activities are not subject to self-employment tax (with or without the mark-to-market election).

Husband-Wife Joint Ventures

Usually when 2 or more people co-own a business, they are in partnership. However, spouses who co-own a business and file jointly and conduct a joint venture can opt not to be treated as a partnership, which requires filing a partnership return (Form 1065) and reporting 2 Schedule K-1s (as explained later in this chapter). Instead, these “couplepreneurs” each report their share of income on Schedule C of Form 1040. To qualify for this election, each must materially participate in the business (neither can be a silent partner), and there can be no other co-owners. Making this election simplifies reporting while ensuring that each spouse receives credit for paying Social Security and Medicare taxes.

One-Member Limited Liability Companies

Every state allows a single owner to form a limited liability company (LLC) under state law. From a legal standpoint, an LLC gives the owner protection from personal liability (only business assets are at risk from the claims of creditors) as explained later in this chapter. But from a tax standpoint, a single-member LLC is treated as a “disregarded entity.” (The owner can elect to have the LLC taxed as a corporation, but this is not typical. An election may be made to be taxed as a corporation, followed by an S election, so that the owner can easily make tax payments through wage withholding rather than making estimated tax payments, as well as minimize Social Security and Medicare taxes.) If the owner is an individual (and not a corporation), all of the income and expenses of the LLC are reported on Schedule C of the owner's Form 1040. In other words, for federal income tax purposes, the LLC is treated just like a sole proprietorship.

Tax Treatment of Income and Deductions in General

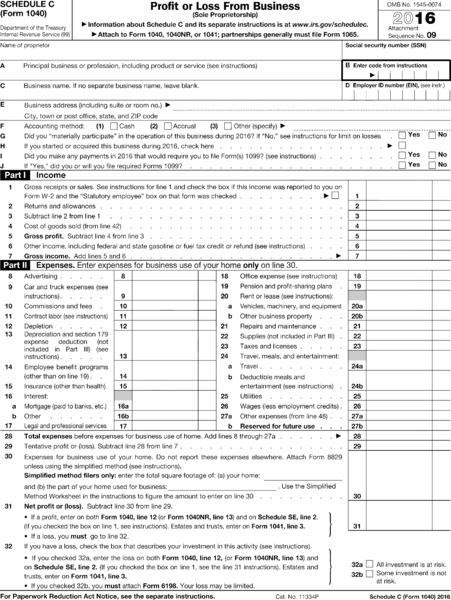

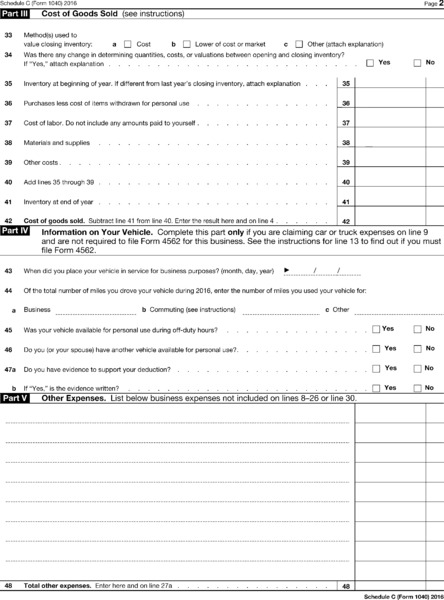

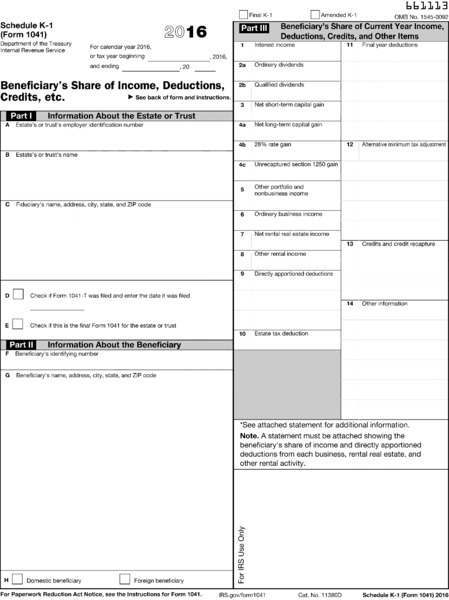

Sole proprietors, including independent contractors and statutory employees, report their income and deductions on Schedule C, see Profit or Loss From Business (Figure 1.1). The net amount (profit or loss after offsetting income with deductions) is then reported as part of the income section on page 1 of your Form 1040. Such individuals may be able to use a simplified form for reporting business income and deductions: Schedule C-EZ, Net Profit From Business (see Figure 1.2). Individuals engaged in farming activities report business income and deductions on Schedule F, the net amount of which is then reported in the income section on page 1 of Form 1040. Individuals who are considered employees cannot use Schedule C to report their income and claim deductions. See page 28 for the tax treatment of income and deductions by employees.

Figure 1.1 Schedule C, Profit or Loss From Business

Figure 1.2 Schedule C-EZ, Net Profit From Business

Partnerships and Limited Liability Companies

If you go into business with others, then you cannot be a sole proprietor (with the exception of a husband-wife joint venture, explained earlier). You are automatically in a partnership if you join together with one or more people to share the profits of the business and take no formal action. Owners of a partnership are called partners.

There are 2 types of partnerships: general partnerships and limited partnerships. In general partnerships, all of the partners are personally liable for the debts of the business. Creditors can go after the personal assets of any and all of the partners to satisfy partnership debts. In limited partnerships (LPs), only the general partners are personally liable for the debts of the business. Limited partners are liable only to the extent of their investments in the business plus their share of recourse debts and obligations to make future investments. Some states allow LPs to become limited liability limited partnerships (LLLPs) to give general partners personal liability protection with respect to the debts of the partnership.

General partners are jointly and severally liable for the business's debts. A creditor can go after any one partner for the full amount of the debt. That partner can seek to recoup a proportional share of the debt from other partner(s).

Partnerships can be informal agreements to share profits and losses of a business venture. More typically, however, they are organized with formal partnership agreements. These agreements detail how income, deductions, gains, losses, and credits are to be split (if there are any special allocations to be made) and what happens on the retirement, disability, bankruptcy, or death of a partner. A limited partnership must have a partnership agreement that complies with state law requirements.

Another form of organization that can be used by those joining together for business is a limited liability company (LLC). This type of business organization is formed under state law in which all owners are given limited liability. Owners of LLCs are called members. These companies are relatively new but have attracted great interest across the country. Every state now has LLC statutes to permit the formation of an LLC within its boundaries. Most states also permit limited liability partnerships (LLPs)—LLCs for accountants, attorneys, doctors, and other professionals—which are easily established by existing partnerships filing an LLP election with the state. A partner in an LLP has personal liability protection with respect to the firm's debts, but remains personally liable for his or her professional actions.

Alabama, Delaware, District of Columbia, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, and Wisconsin (to a limited extent) permit multiple LLCs to operate under a single LLC umbrella called a “series LLC” (each LLC is called a “cell”). The rules are not uniform in all of these states. If you are in a state that does not have a law for series LLC, in most but not all states you can form the series in Delaware, for example, and then register to do business in your state. The debts and liabilities of each LLC remain separate from those of the other LLCs, something that is ideal for those owning several pieces of real estate—each can be owned by a separate LLC under the master LLC as long as each LLC maintains separate bank accounts and financial records. At present, state law is evolving to determine the treatment of LLCs formed in one state but doing business in another.

As the name suggests, the creditors of LLCs can look only to the assets of the company to satisfy debts; creditors cannot go after members and hope to recover their personal assets.

Tax Treatment of Income and Deductions in General

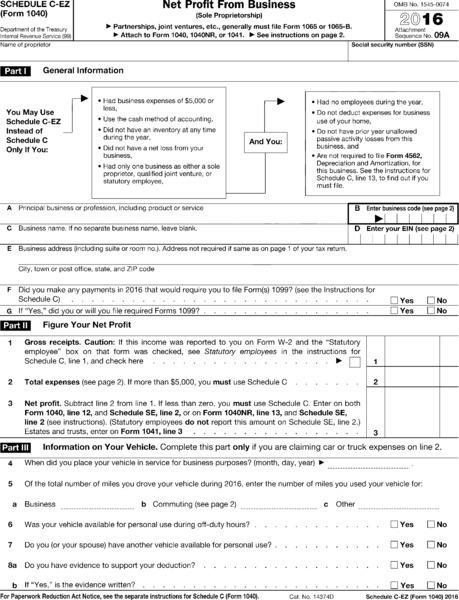

Partnerships are pass-through entities. They are not separate taxpaying entities; instead, they pass income, deductions, gains, losses, and tax credits through to their owners. More than 27 million partners file more than 3 million partnership returns each year. Of these, 66% are limited liability companies, representing the most prevalent type of entity filing a partnership return; more common than general partnerships or limited partnerships. The owners report these amounts on their individual returns. While the entity does not pay taxes, it must file an information return with IRS Form 1065, U.S. Return of Partnership Income, to report the total pass-through amounts. Even though the return is called a partnership return, it is the same return filed by LLCs with 2 or more owners who do not elect to be taxed as a corporation. The entity also completes Schedule K-1 of Form 1065 (Figure 1.3), a copy of which is given to each owner. The K-1 tells the owner his or her allocable share of partnership/LLC amounts. Like W-2 forms used by the IRS to match employees’ reporting of their compensation, the IRS employs computer matching of Schedules K-1 to ensure that owners are properly reporting their share of their business's income.

Figure 1.3 Schedule K-1, Partner's Share of Income, Deductions, Credits, etc.

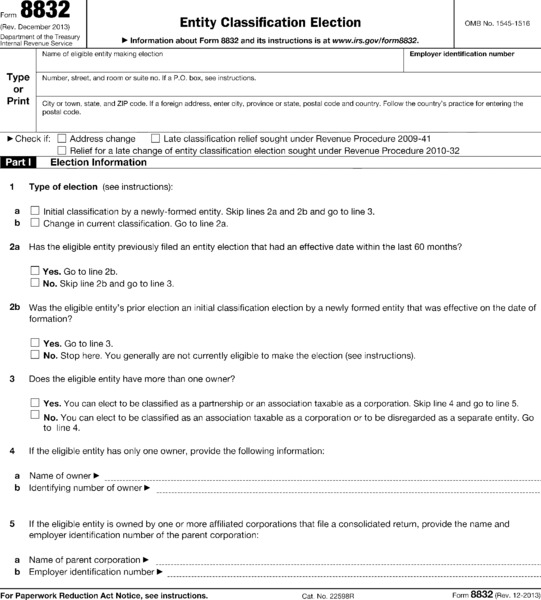

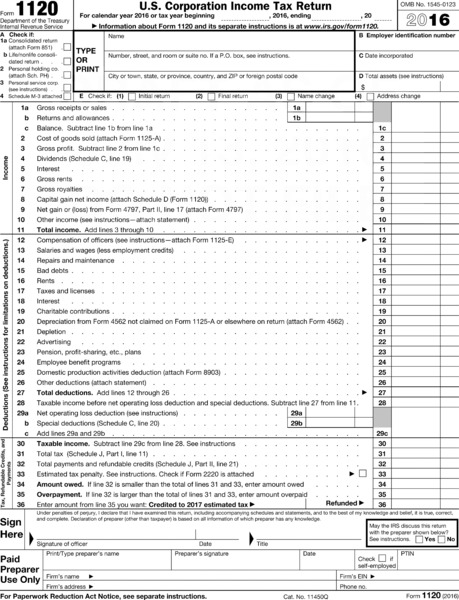

For federal income tax purposes, LLCs are treated like partnerships unless the members elect to have the LLCs taxed as corporations. This is done on IRS Form 8832, Entity Classification Election. See Figure 1.4. For purposes of our discussion throughout the book, it will be assumed that LLCs have not chosen corporate tax treatment and so are taxed the same way as partnerships. A single-member LLC is treated for tax purposes like a sole proprietor if it is owned by an individual who reports the company's income and expenses on his or her Schedule C. Under proposed regulations, for federal tax purposes a series LLC is treated as an entity formed under local law, whether or not local law treats the series as a separate legal entity. The tax treatment of the series is then governed by the check-the-box rules.

Figure 1.4 Form 8832, Entity Classification Election

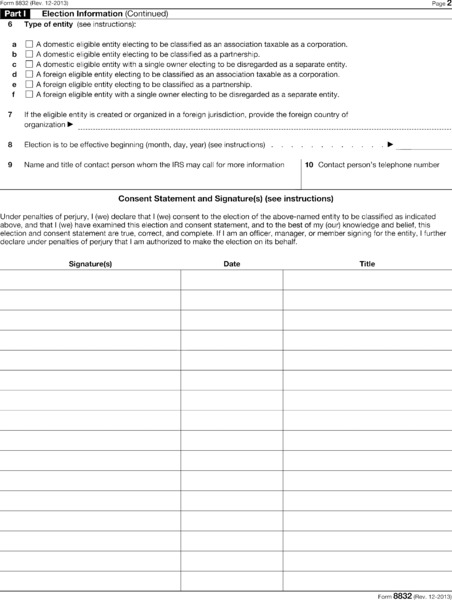

Figure 1.5 Schedule E, Part II, Income or Loss From Partnerships and S Corporations

There are 2 types of items that pass through to an owner: trade or business income or loss and separately stated items. A partner's or member's share is called the distributive share. Trade or business income or loss takes into account most ordinary deductions of the business—compensation, rent, taxes, interest, and so forth. Guaranteed payments to an owner are also taken into account when determining ordinary income or loss. From an owner's perspective, deductions net out against income from the business, and the owner's allocable share of the net amount is then reported on the owner's Schedule E of Form 1040. Figure 1.5 shows a sample portion of Schedule E on which a partner's or member's distributive share is reported.

Separately stated items are stand-alone items that pass through to owners apart from the net amount of trade or business income. These are items that are subject to limitations on an individual's tax return and must be segregated from the net amount of trade or business income. They are reported along with similar items on the owner's own tax return.

Other items that pass through separately to owners include capital gains and losses, Section 179 (first-year expensing) deductions, investment interest deductions, and tax credits.

When a partnership or LLC has substantial expenses that exceed its operating income, a loss is passed through to the owner. A number of different rules operate to limit a loss deduction. The owner may not be able to claim the entire loss. The loss is limited by the owner's basis, or the amount of cash and property contributed to the partnership, in the interest in the partnership.

There may be additional limits on your write-offs from partnerships and LLCs. If you are a passive investor—a silent partner—in these businesses, your loss deduction is further limited by the passive activity loss rules. In general, these rules limit a current deduction for losses from passive activities to the extent of income from passive activities. Additionally, losses are limited by the individual's economic risk in the business. This limit is called the at-risk rule. The passive activity loss and at-risk rules are discussed in Chapter 4. For a further discussion of the passive activity loss rules, see IRS Publication 925, Passive Activity and At-Risk Rules.

S Corporations and Their Shareholder-Employees

There were more than 4.7 million S corporations in the government's 2015 fiscal year, making these entities the most prevalent type of corporation. About 68% of all corporations file a Form 1120S, the return for S corporations. About 78% of S corporations have only 1, 2, or 3 shareholders.

S corporations are like regular corporations (called C corporations) for business law purposes. They are separate entities in the eyes of the law and exist independently from their owners. For example, if an owner dies, the S corporation's existence continues. S corporations are formed under state law in the same way as other corporations. The only difference between S corporations and other corporations is their tax treatment for federal income tax purposes.

For the most part, S corporations are treated as pass-through entities for federal income tax purposes. This means that, as with partnerships and LLCs, the income and loss pass through to owners, and their allocable share is reported by S corporation shareholders on their individual income tax returns. The tax treatment of S corporations is discussed more fully later in this chapter.

S corporation status is not automatic. A corporation must elect S status in a timely manner. This election is made on Form 2553, Election by Small Business Corporations to Tax Corporate Income Directly to Shareholders. It must be filed with the IRS no later than the fifteenth day of the third month of the corporation's tax year.

If an S election is filed after the deadline, it is automatically effective for the following year. A corporation can simply decide to make a prospective election by filing at any time during the year prior to that for which the election is to be effective. However, if you want the election to be effective now but missed the deadline, you may qualify for relief under Rev. Proc. 2013–30 (see the instructions to Form 2553 for making a late election).

To be eligible for an S election, the corporation must meet certain shareholder requirements. There can be no more than 100 shareholders. For this purpose, all family members (up to 6 generations) are treated as a single shareholder. Only certain types of trusts are permitted to be shareholders. There can be no nonresident alien shareholders.

An election cannot be made before the corporation is formed. The board of directors of the corporation must agree to the election and should indicate this assent in the minutes of a board of directors meeting.

Remember, if state law also allows S status, a separate election may have to be filed with the state. Check with all state law requirements.

Tax Treatment of Income and Deductions in General

For the most part, S corporations, like partnerships and LLCs, are pass-through entities. They are generally not separate taxpaying entities. Instead, they pass through to their shareholders’ income, deductions, gains, losses, and tax credits. The shareholders report these amounts on their individual returns. The S corporation files a return with the IRS—Form 1120S, U.S. Income Tax Return for an S Corporation—to report the total pass-through amounts. The S corporation also completes Schedule K-1 of Form 1120S, a copy of which is given to each shareholder. The K-1 tells the shareholder his or her allocable share of S corporation amounts. The K-1 for S corporation shareholders is similar to the K-1 for partners and LLC members.

Unlike partnerships and LLCs, however, S corporations may become taxpayers if they have certain types of income. There are only 3 types of income that result in a tax on the S corporation. These 3 items cannot be reduced by any deductions:

Built-in gains. These are gains related to appreciation of assets held by a C corporation that converts to S status. Thus, if a corporation is formed and immediately elects S status, there will never be any built-in gains to worry about. The built-in gains tax ends once the S corporation has held the appreciated assets for more than 5 years.

Passive investment income. This is income of a corporation that has earnings and profits from a time when it was a C corporation. A tax on the S corporation results only when this passive investment income exceeds 25% of gross receipts. Again, if a corporation is formed and immediately elects S status, or if a corporation that converted to S status does not have any earnings and profits at the time of conversion, then there will never be any tax from this source.

LIFO recapture. When a C corporation using last-in, first-out or LIFO to report inventory converts to S status, there may be recapture income that is taken into account partly on the C corporation's final return, but also on the S corporation's return. Again, if a corporation is formed and immediately elects S status, there will not be any recapture income on which the S corporation must pay tax.

To sum up, if a corporation is formed and immediately elects S status, the corporation will always be solely a pass-through entity and there will never be any tax at the corporate level. If the S corporation was, at one time, a C corporation, there may be some tax at the corporate level.

C Corporations and Their Shareholder-Employees

A C corporation is an entity separate and apart from its owners; it has its own legal existence. Though formed under state law, it need not be formed in the state in which the business operates. Many corporations, for example, are formed in Delaware or Nevada because the laws in these states favor the corporation, as opposed to the investors (shareholders). However, state law for the state in which the business operates may still require the corporation to make some formal notification of doing business in the state. The corporation may also be subject to tax on income generated in that state.

According to IRS data, there are about 2.2 million C corporations, more than 98% of which are small or midsize companies (with assets of $10 million or less).

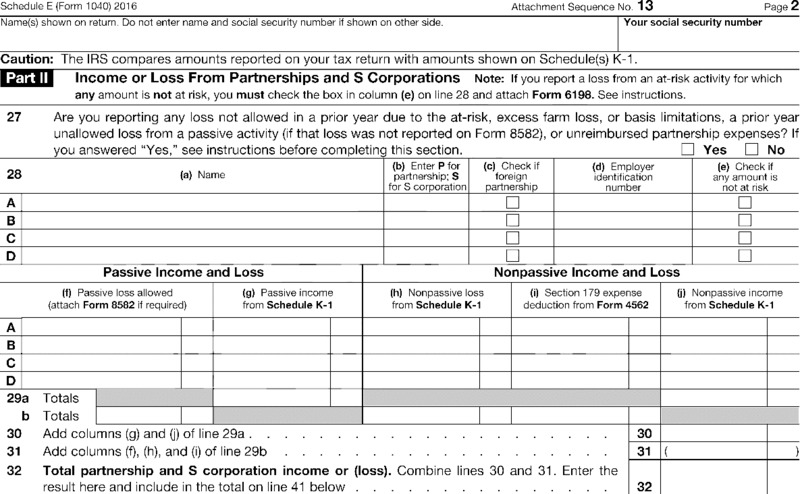

For federal tax purposes, a C corporation is a separate taxpaying entity. It files its own return (Form 1120, U.S. Corporation Income Tax Return) to report its income or losses. Shareholders do not report their share of the corporation's income. The tax treatment of C corporations is explained more fully later in this chapter.

Personal Service Corporations

Professionals who incorporate their practices are a special type of C corporation called personal service corporations (PSCs).

Personal service corporations are subject to special rules in the tax law. Some of these rules are beneficial; others are not. Personal service corporations:

Cannot use graduated corporate tax rates; they are subject to a flat tax rate of 35%.

Are generally required to use the same tax year as that of their owners. Typically, individuals report their income on a calendar year basis (explained more fully in Chapter 2), so their PSCs must also use a calendar year. However, there is a special election that can be made to use a fiscal year.

Can use the cash method of accounting. Other C corporations cannot use the cash method and instead must use the accrual method (explained more fully in Chapter 2).

Are subject to the passive loss limitation rules (explained in Chapter 4).

Can have their income and deductions reallocated by the IRS between the corporation and the shareholders if it more correctly reflects the economics of the situation.

Have a smaller exemption from the accumulated earnings penalty than other C corporations. This penalty imposes an additional tax on corporations that accumulate their income above and beyond the reasonable needs of the business instead of distributing income to shareholders.

Tax Treatment of Income and Deductions in General

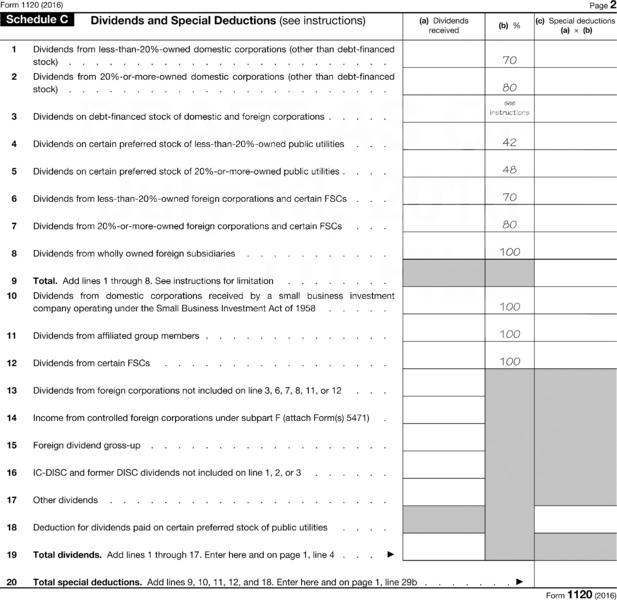

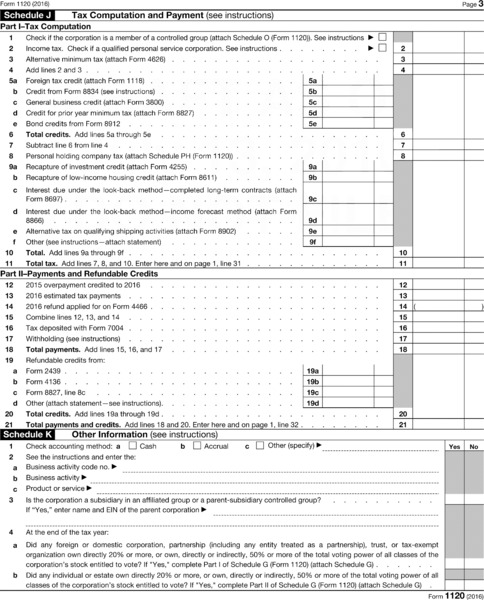

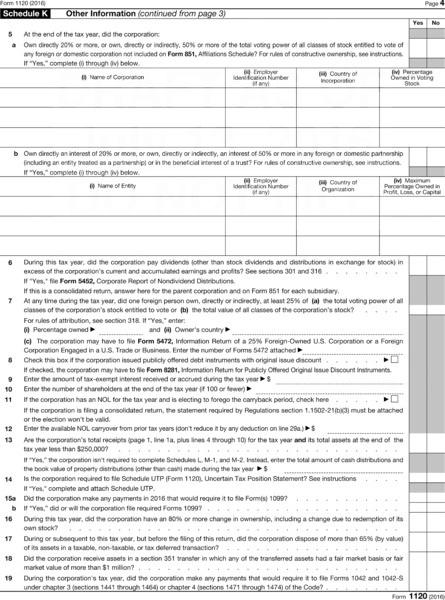

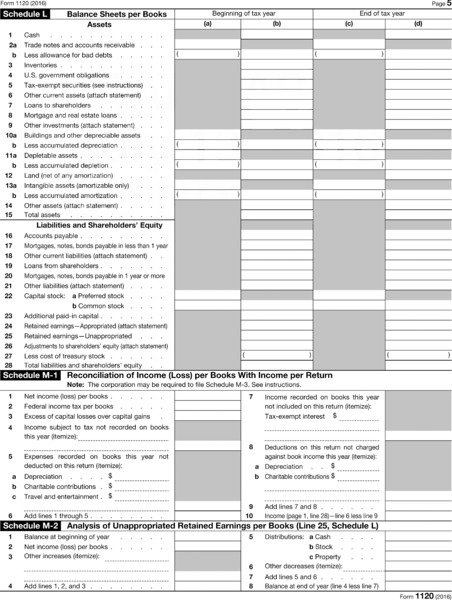

The C corporation reports its own income and claims its own deductions on Form 1120, U.S. Corporation Income Tax Return. Shareholders in C corporations do not have to report any income of the corporation (and cannot claim any deductions of the corporation). Figure 1.6 shows a sample copy of page 1 of Form 1120.

C corporations pay taxes according to corporate tax rates that run from 15% on taxable income up to $50,000, to 35% on taxable income over $15 million (with very large corporations subject to a higher marginal rate that has the effect of eliminating the graduated rates so that they are eventually taxed at a flat 35%) (see Table 1.1). These brackets are not adjusted annually for inflation as are the tax brackets for individuals.

Table 1.1 Federal Corporate Tax Rate Schedule

| If taxable income is: | |||

| Over | But Not Over | Tax Is | Of the Amount Over |

$ 0 |

$ 50,000 |

15% |

$ 0 |

50,000 |

75,000 |

$ 7,500 + 25% |

50,000 |

75,000 |

100,000 |

$ 13,750 + 34% |

75,000 |

100,000 |

335,000 |

$ 22,250 + 39% |

100,000 |

335,000 |

10,000,000 |

$ 113,900 + 34% |

335,000 |

10,000,000 |

15,000,000 |

$ 3,400,000 + 35% |

10,000,000 |

15,000,000 |

18,333,333 |

$ 5,150,000 + 38% |

15,000,000 |

18,333,333 |

35% |

0 |

|

There has been sentiment in Congress to reduce significantly the top corporate rate in order to make U.S. corporations more competitive with foreign corporations. For example, in Singapore the rate is 17%, in South Korea, 24%, in Canada 26%, and in Germany, 30%. Japan reduced its rate from 40% (the highest in industrialized countries) to 38%, leaving the United States with the highest rate (an effective rate of 40% after averaging in state corporate tax rates).

Distributions from the C corporation to its shareholders are personal items for the shareholders. For example, if a shareholder works for his or her C corporation and receives a salary, the corporation deducts that salary against corporate income. The shareholder reports the salary as income on his or her individual income tax return. If the corporation distributes a dividend to the shareholder, again, the shareholder reports the dividend as income on his or her individual income tax return. In the case of dividends, however, the corporation cannot claim a deduction. This, then, creates a 2-tier tax system, commonly referred to as double taxation. First, earnings are taxed at the corporate level. Then, when they are distributed to shareholders as dividends, they are taxed again, this time at the shareholder level. There has been sentiment in Congress over the years to eliminate the double taxation, but as of yet there has been no legislation to accomplish this end other than the relief provided by capping the rate on dividends (zero for individuals in the 10% or 15% tax bracket; 15% for those in the 25%, 28%, 33%, or 35% brackets; 20% for those in the 39.6% bracket).

Figure 1.6 Form 1120, U.S. Corporation Income Tax Return

Other Tax Issues for C Corporations

In view of the favorable corporate rate tax structure (compared with the individual tax rates), certain tax penalties prevent businesses from using this form of business organization to optimum advantage.

Personal holding company penalty. Corporations that function as a shareholder investment portfolio rather than as an operating company may fall subject to the personal holding corporation (PHC) penalty tax of 20% on certain undistributed corporate income. The tax rules strictly define a PHC according to stock ownership and adjusted gross income. The penalty may be avoided by not triggering the definition of PHC or by paying out certain dividends.

Accumulated earnings tax. Corporations may seek to keep money in corporate accounts rather than distribute it as dividends to shareholders with the view that an eventual sale of the business will enable shareholders to extract those funds at capital gain rates. Unfortunately, the tax law imposes a penalty on excess accumulations at 20%. Excess accumulations are those above an exemption amount ($250,000 for most businesses, but only $150,000 for PSCs) plus amounts for the reasonable needs of the business. Thus, for example, amounts retained to finance planned construction costs, to pay for a possible legal liability, or to buy out a retiring owner are reasonable needs not subject to penalty regardless of amount.

Employees

If you do not own any interest in a business but are employed by one, you may still have to account for business expenses. Your salary or other compensation is reported as wages in the income section as seen on page 1 of your Form 1040. Your deductions (with a few exceptions), however, can be claimed only as miscellaneous itemized deductions on Schedule A. These deductions are subject to 2 limitations. The total is deductible only if it exceeds 2% of adjusted gross income and, if your income exceeds a threshold amount that depends on your filing status, the otherwise deductible portion of miscellaneous itemized deductions reduced by a phase-out. For 2016, the threshold amount at which itemized deductions (including miscellaneous itemized deductions) begins to phase out is $259,400 for singles; $285,350 for heads of households; $311,300 for joint filers; and $155,650 for married persons filing separately.

Under the 2% rule, only the portion of total miscellaneous deductions in excess of 2% of adjusted gross income is deductible on Schedule A. Adjusted gross income is the tax term for your total income subject to tax (gross income) minus business expenses (other than employee business expenses), capital losses, and certain other expenses that are deductible even if you do not claim itemized deductions, such as qualifying IRA contributions or alimony. You arrive at your adjusted gross income by completing the Income and Adjusted Gross Income sections on page 1 of Form 1040.

If you fall into a special category of employees called statutory employees, you can deduct your business expenses on Schedule C instead of Schedule A. Statutory employees were discussed earlier in this chapter.

Factors in Choosing Your Form of Business Organization

Throughout this chapter, the differences of how income and deductions are reported have been explained for different entities, but these differences are not the only reasons for choosing a form of business organization. When you are deciding on which form of business organization to choose, tax, financial, and many other factors come into play, including:

Personal liability

Access to capital

Lack of profitability

Fringe benefits

Nature and number of owners

Tax rates

Social Security and Medicare taxes

Restrictions on accounting periods and account methods

Owner's payment of company expenses

Multistate operations

Audit chances

Filing deadlines and extensions

Exit strategy

Each of these factors is discussed below.

Personal Liability

If your business owes money to another party, are your personal assets—home, car, investment—at risk? The answer depends on your form of business organization. You have personal liability—your personal assets are at risk—if you are a sole proprietor or a general partner in a partnership. In all other cases, you do not have personal liability. Thus, for example, if you are a shareholder in an S corporation, you do not have personal liability for the debts of your corporation.

Of course, you can protect yourself against personal liability for some types of occurrences by having adequate insurance coverage. For example, if you are a sole proprietor who runs a store, be sure that you have adequate liability coverage in the event someone is injured on your premises and sues you.

Even if your form of business organization provides personal liability protection, you can become personally liable if you agree to it in a contract. For example, some banks may not be willing to lend money to a small corporation unless you, as a principal shareholder, agree to guarantee the corporation's debt. For example, SBA loans usually require the personal guarantee of any owner with a 20% or more ownership interest in the business. In this case, you are personally liable to the extent of the loan to the corporation. If the corporation does not or cannot repay the loan, then the bank can look to you, and your personal assets, for repayment.

There is another instance in which corporate or LLC status will not provide you with personal protection. Even if you have a corporation or LLC, you can be personally liable for failing to withhold and deposit payroll taxes, which are called trust fund taxes (employees’ income tax withholding and their share of FICA taxes, which are held in trust for them) to the IRS. This liability is explained in Chapter 29.

Access to Capital

Most small businesses start up using an owner's personal resources or by turning to family and friends. However, some businesses need outside capital—equity and/or debt—to get started properly. A C corporation may make it easier to raise money, especially now. For example, access to equity crowdfunding, which allows businesses to raise small amounts from numerous investors, is effectively limited to C corporations (S corporations cannot have more than 100 investors; partnerships and LLCs would have difficulty in divvying up ownership among an ever-changing number of owners). Equity crowdfunding for accredited investors (net worth more than $1 million excluding a principal residence or income exceeding $300,000) obviously works best for C corporations.

For non-accredited investors (those who do not qualify as accredited investors because they don't have annual income of $200,000, or $300,000 with a spouse), equity crowdfunding investments are capped at up to 10% of annual income for those with income over $100,000, or up to $2,000 or 5% of annual income, whichever is greater, for investors with annual income under $100,000.

Lack of Profitability

All businesses hope to make money. But many sustain losses, especially in the start-up years and during tough economic times. The way in which a business is organized affects how losses are treated.

Pass-through entities allow owners to deduct their share of the company's losses on their personal returns (subject to limits discussed in Chapter 4). If a business is set up as a C corporation, only the corporation can deduct losses. Thus, when losses are anticipated, for example in the start-up phase, a pass-through entity generally is a preferable form of business organization. However, once the business becomes profitable, the tables turn. In that situation, C corporations can offer more tax opportunities, such as fringe benefits. Companies that suffer severe losses may be forced into bankruptcy. The bankruptcy rules for corporations (C or S) are very different from the rules for other entities (see Chapter 25).

Fringe Benefits

The tax law gives employees of corporations the opportunity to enjoy special fringe benefits on a tax-free basis. They can receive employer-provided group term life insurance up to $50,000, health insurance coverage, dependent care assistance up to $5,000, education assistance up to $5,250, adoption assistance, and more. They can also be covered by medical reimbursement plans. This same opportunity is not extended to sole proprietors. Remember that sole proprietors are not employees, so they cannot get the benefits given only to employees. Similarly, partners, LLC members, and even S corporation shareholders who own more than 2% of the stock in their corporations are not considered employees and thus not eligible for fringe benefits.

If the business can afford to provide these benefits, the form of business becomes important. All forms of business can offer tax-favored retirement plans. Corporations make it possible to give ownership opportunities to employees. Corporations—both C and S—can offer employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs) in which employees receive ownership interests through a plan that is much like a qualified retirement plan (see Chapter 16). Certain C corporations can offer employees an income tax exclusion opportunity for stock they buy or receive as compensation. For 2016, 50%, 75%, or 100% of the gain on the sale of qualified small business stock (explained in Chapter 7) is excludable from gross income, depending on when the stock was acquired, as long as the stock has been held for more than five years. C corporations can also offer incentive stock option (ISO) plans and nonqualified stock option (NSO) plans (see Chapter 7). The tax law does not bar S corporations from offering stock option plans, but because of the 100-shareholder limit (discussed earlier in this chapter), it becomes difficult to do so.

Nature and Number of Owners

With whom you go into business affects your choice of business organization. For example, if you have any foreign investors, you cannot use an S corporation, because foreign individuals are not permitted to own S corporation stock directly (resident aliens are permitted to own S corporation stock). An S corporation also cannot be used if investors are partnerships or corporations. In other words, in order to use an S corporation, all shareholders must be individuals who are not nonresident aliens (there are exceptions for estates, certain trusts, and certain exempt organizations).

The number of owners also presents limits on your choice of business organization. If you are the only owner, then your choices are limited to a sole proprietorship or a corporation (either C or S). All states allow single-member LLCs. If you have more than one owner, you can set up the business in just about any way you choose. S corporations cannot have more than 100 shareholders, but this number provides great leeway for small businesses.

If you have a business already formed as a C corporation and want to start another corporation, you must take into consideration the impact of special tax rules for multiple corporations. These rules apply regardless of the size of the business, the number of employees you have, and the profit the businesses make. Multiple corporations are corporations under common control, meaning they are essentially owned by the same parties. The tax law limits the number of tax breaks in the case of multiple corporations. Instead of each corporation enjoying a full tax benefit, the benefit must be shared among all of the corporations in the group. For example, the tax brackets for corporations are graduated. In the case of certain multiple corporations, however, the benefit of the graduated rates must be shared. In effect, each corporation pays a slightly higher tax because it is part of a group of multiple corporations. If you want to avoid restrictions on multiple corporations, you may want to look to LLCs or some other form of business organization.

Tax Rates

Both individuals and C corporations (other than PSCs) can enjoy graduated income tax rates. The top tax rate paid by sole proprietors and owners of other pass-through businesses is 39.6%. The top corporate tax rate imposed on C corporations is 35%. (There is some political support for reducing the top corporate tax rate.) Personal service corporations are subject to a flat tax rate of 35%. (The domestic production activities deduction in Chapter 21 effectively lowers the top rate to less than 32% for corporations that are eligible to claim it.) But remember, even though the C corporation has a lower top tax rate, there is a 2-tier tax structure with which to contend if earnings are paid out to you as dividends—tax at the corporate level and again at the shareholder level.

While the so-called double taxation for C corporations has been eased by lowering the tax rate on dividends, there is still some double tax because dividends remain nondeductible at the corporate level. The rate on qualified dividends for most taxpayers is 15% (zero for taxpayers who are in the 10% or 15% tax bracket; 20% for those in the 39.6% tax bracket).

The tax rates on capital gains also differ between C corporations and other taxpayers. This is because capital gains of C corporations are not subject to special tax rates (they are taxed the same as ordinary business income), while owners of other types of businesses may pay tax on the business's capital gains at no more than 15% (zero if they are in the 10% or 15% tax bracket; 20% if they are in the 39.6% tax bracket). Of course, tax rates alone should not be the determining factor in selecting your form of business organization.

Social Security and Medicare Taxes

Owners of businesses organized any way other than as a corporation (C or S) are not employees of their businesses. As such, they are personally responsible for paying Social Security and Medicare taxes (called self-employment taxes for owners of unincorporated businesses). This tax is made up of the employer and employee shares of Social Security and Medicare taxes. The deduction for one-half of self-employment taxes is explained in Chapter 13.

However, owners of corporations have these taxes applied only against their salary and taxable benefits. Owners of unincorporated businesses pay self-employment tax on net earnings from self-employment. This essentially means profits, whether they are distributed to the owners or reinvested in the business. The result: Owners of unincorporated businesses can wind up paying higher Social Security and Medicare taxes than comparable owners who work for their corporations. On the other hand, in unprofitable businesses, owners of unincorporated businesses may not be able to earn any Social Security credits, while corporate owners can have salary paid to them on which Social Security credits can be generated.

There have been proposals to treat certain S corporation owner-employees like partners for purposes of self-employment tax. To date, these proposals have failed, but could be revived in the future.

The additional Medicare surtaxes on earned income and net investment income (NII) are yet another factor to consider. The 0.9% surtax on earned income applies to taxable compensation (e.g., wages, bonuses, commissions, and taxable fringe benefits) of shareholders in S or C corporations; it applies to all net earnings from self-employment for sole proprietors, partners, and limited liability company members. The 3.8% NII tax applies to business income passed through from an entity in which the owner does not materially participate (i.e., one in which the owner is effectively a silent investor).

Restrictions on Accounting Periods and Accounting Methods

As you will see in Chapter 2, the tax law limits the use of fiscal years and the cash method of accounting for certain types of business organizations. For example, partnerships and S corporations in general are required to use a calendar year to report income.

Also, C corporations generally are required to use the accrual method of accounting to report income. There are exceptions to both of these rules. However, as you can see, accounting periods and accounting methods are important considerations in choosing your form of business organization.

Owner's Payment of Company Expenses

In small businesses it is common practice for owners to pay certain business expenses out of their own pockets—either as a matter of convenience or because the company is short of cash. The type of entity dictates where owners can deduct these payments.

A partner who is not reimbursed for paying partnership expenses can deduct his or her payments of these expenses as an above-the-line deduction (on a separate line on Schedule E of the partner's Form 1040, which should be marked as “UPE”), as long as the partnership agreement requires the partner to pay specified expenses personally and includes language that no reimbursement will be made.

A shareholder in a corporation (S or C) is an employee, so that unreimbursed expenses paid on behalf of the corporation are treated as unreimbursed employee business expenses reported on Form 2106 and deducted as a miscellaneous itemized deduction on Schedule A of the shareholder's Form 1040. Only total miscellaneous itemized deductions in excess of 2% of the shareholder's adjusted gross income are allowable; if the shareholder is subject to the alternative minimum tax, the benefit from this deduction is lost.

However, shareholders can avoid this deduction problem by having the corporation adopt an accountable plan to reimburse their out-of-pocket expenses. An accountable plan allows the corporation to deduct the expenses, while the shareholders do not report income from the reimbursement (see Chapter 8).

Multistate Operations

Each state has its own way of taxing businesses subject to its jurisdiction. The way in which a business is organized for federal income tax purposes may not necessarily control for state income tax purposes. For example, some states do not recognize S corporation elections and tax such entities as regular corporations.

A company must file a return in each state in which it does business and pay income tax on the portion of its profits earned in that state. Income tax liability is based on having a nexus, or connection, to a state. This is not always an easy matter to settle. Where there is a physical presence—for example, a company maintains an office—then there is a clear nexus. But when a company merely makes sales to customers within a state or offers goods for sale from a website, there is generally no nexus. (However, a growing number of states are liberalizing the definition of nexus in order to get more businesses to pay state taxes so they can increase revenue; some states are moving toward “a significant economic presence,” meaning taking advantage of a state's economy to produce income, as a basis for taxation.)

Assuming that a company does conduct multistate business, then its form of organization becomes important. Most multistate businesses are C corporations because only one corporate income tax return needs to be filed in each state where they do business. Doing business as a pass-through entity means that each owner would have to file a tax return in each state the company does business.

Audit Chances

Each year the IRS publishes statistics on the number and type of audits it conducts. The rates for the government's fiscal year 2015, the most recent year for which statistics are available, show a very low overall audit activity of business returns.

The chances of being audited vary with the type of business organization, the amount of income generated by the business, and the geographic location of the business. While the chance of an audit is not a significant reason for choosing one form of business organization over another, it is helpful to keep these statistics in mind.

Table 1.2 sheds some light on your chances of being audited, based on the most recently available statistics.

Table 1.2 Percentage of Returns Audited

| FY 2014* | FY 2015* | |

| Sole proprietors (Schedule C) (based on gross receipts) | ||

| Under $25,000 | 1.0% | 0.9% |

| $25,000 to under $100,000 | 1.9 | 2.4 |

| $100,000 to under $200,000 | 2.4 | 2.5 |

| $200,000 or more | 2.1 | 2.0 |

| Farming (Schedule F) (based on gross receipts) | ||

| All farm returns | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| Partnerships | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| S corporations | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| C corporations (based on assets) | ||

| Under $250,000 | 0.9 | 0.8 |

| $250,000 to under $1 million | 1.2 | 1.3 |

| $1 million to under $5 million | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| $5 million to under $10 million | 1.9 | 1.5 |

*Fiscal year from October 1 to September 30.

Source: IRS Data Book.

Many tax experts agree that your location can impact your audit changes. Some IRS offices are better staffed than others. There have been no recent statistics identifying these high-audit locations.

Past audit rates are no guarantee of the likelihood of future IRS examinations. The $458 billion tax gap for 2008–2010 (the most recent statistics), which represents the spread between what the government is owed and what it collects, has been blamed in large part on those sole proprietors/independent contractors who underreport income or overstate deductions. While the IRS has indicated that it would increase audits of certain sole proprietors and other small businesses, due to budgetary constraints, the number of audits is on the decline.

Filing Deadlines and Extensions

How your business is organized dictates when its tax return must be filed, the form to use, and the additional time that can be obtained for filing the return. In the past, calendar-year S corporations had to file their income tax returns by March 15 and could obtain a 6-month filing extension to September 15. In contrast, calendar-year limited liability companies were required to file their income tax returns by April 15 but could only obtain a 5-month filing extension to September 15. Now, however, some of the filing and extension deadlines have changed; the changes affect 2016 returns filed in 2017. The filing deadline for partnerships has been moved up to March 15, but they now have a 6-month filing extension. The deadline for C corporations has been pushed back to April 15 (the same deadline for individuals, including Schedule C filers); they currently have only a 5-month extension to September 15 (but will be 6 months, to October 15, starting in 2026). The September 15 extended due date gives S corporations, limited liability companies, and partnerships time to provide Schedule K-1 to owners so they can file their personal returns by their extended due date of October 15.

Table 1.3 lists the filing deadlines for calendar-year businesses, the available automatic extensions, and the forms to use in filing the return or requesting a filing extension. Note that these dates are extended to the next business day when a deadline falls on a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday.

Table 1.3 Filing Deadlines, Extensions, and Forms for 2016 Returns

| Form to | ||||

| Automatic | Request | |||

| Type of | Return | Income Tax | Filing | Filing |

| Entity | Due Date | Return | Extension | Extension |

| Sole proprietorship | April 15* | Schedule C of Form 1040 | October 15** | Form 4868 |

| Partnership/LLC | March 15 | Form 1065 | September 15 | Form 7004 |

| S corporation | March 15 | Form 1120S | September 15 | Form 7004 |

| C corporation | April 15 | Form 1120 | September 15 | Form 7004 |

*The scheduled due date is April 18, 2017.

**The scheduled due date is October 16, 2017, because October 15 falls on a Sunday.

Exit Strategy

The tax treatment on the termination of a business is another factor to consider. While the choice of entity is made when the business starts out, you cannot ignore the tax consequences that this choice will have when the business terminates, is sold, or goes public. The liquidation of a C corporation usually produces a double tax—at the entity and owner levels. The liquidation of an S corporation produces a double tax only if there is a built-in gains tax issue—created by having appreciated assets in the business when an S election is made. However, the built-in gains tax problem disappears a certain number of years after the S election, so termination after that time does not result in a double tax.

If you plan to sell the business some time in the future, again your choice of entity may have an impact on the tax consequences of the sale. The sale of a sole proprietorship is viewed as a sale of the underlying assets of the business; some may produce ordinary income while others trigger capital gains. In contrast, the sale of qualified small business stock, which is stock in a C corporation, may result in tax-free treatment under certain conditions. Sales of business interests are discussed in Chapter 5.

If the termination of the business results in a loss, different tax rules come into play. Losses from partnerships and LLCs are treated as capital losses (explained in Chapter 5). A shareholder's losses from the termination of a C or S corporation may qualify as a Section 1244 loss—treated as an ordinary loss within limits (explained in Chapter 5).

If the business goes bankrupt, the entity type influences the type of bankruptcy filing to be used and whether the owners can escape personal liability for the debts of the business. Bankruptcy is discussed in Chapter 25.

Forms of Business Organization Compared

So far, you have learned about the various forms of business organization. Which form is right for your business? The answer is really a judgment call based on all the factors previously discussed. You can, of course, use different forms of business organization for your different business activities. For example, you may have a C corporation and personally own the building in which it operates— directly or through an LLC. Or you may be in partnership for your professional activities, while running a sideline business as an S corporation.

Table 1.4 summarizes 2 important considerations: how the type of business organization is formed and what effect the form of business organization has on where income and deductions are reported.

Table 1.4 Comparison of Forms of Business Organization

| Type of Business | How It Is Formed | Where Income and Deductions Are Reported |

| Sole proprietorship | No special requirements | On owner's Schedule C or C-EZ (Schedule F for farming) |

| Partnership | No special requirements | Some items taken into account in figuring trade or business income directly on Form 1065 (allocable amount claimed on partner's Schedule E); separately stated items are passed through to partners and claimed in various places on partner's tax return. |

| Limited special partnership | Some items taken into account in figuring partnership under state law | Trade or business income directly on Form 1065 (allocable amount claimed on partner's Schedule E); separately stated items passed through to partners and claimed in various places on partner's tax return |

| Limited liability company | Organized as such under state law | Some items taken into account in figuring trade or business income directly on Form 1065 (allocable amount claimed on member's Schedule E); separately stated items passed through to members and claimed in various places on member's tax return |

| Limited liability partnership | Organized as such under state law | Some items taken into account in figuring trade or business income directly on Form 1065 (allocable amount claimed on member's Schedule E); separately stated items passed through to members and claimed in various places on member's tax return |

| S corporation | Formed as corporation under state law; tax status elected by filing with IRS | Some items taken into account in figuring trade or business income directly on Form 1120S (allocable amount claimed on shareholder's Schedule E); separately stated items passed through to shareholders and claimed in various places on shareholder's tax return |

| C corporation | Formed under state law | Claimed by corporation in figuring its trade or business income on Form 1120 |

| Employee | No ownership interest | Income reported as wages; deductions as itemized deductions on Schedule A (certain expenses first figured on Form 2106) |

| Independent contractor | No ownership interest in a business | Claimed on individual's Schedule C |

Changing Your Form of Business

Suppose you have a business that you have been running as a sole proprietorship. Now you want to make a change. Your new choice of business organization is dictated by the reason for the change. If you are taking in a partner, you would consider these alternatives: partnership, LLC, S corporation, or C corporation. If you are not taking in a partner, but want to obtain limited personal liability, you would consider an LLC (if your state permits a one-person LLC), an S corporation, or a C corporation. If you are looking to take advantage of certain fringe benefits, such as medical reimbursement plans, you would consider only a C corporation.

Whatever your reason, changing from a sole proprietorship to another type of business organization generally does not entail tax costs on making the changeover. You can set up a partnership or corporation, transfer your business assets to it, obtain an ownership interest in the new entity, and do all this on a tax-free basis. You may, however, have some tax consequences if you transfer your business liabilities to the new entity.

But what if you now have a corporation or partnership and want to change your form of business organization? This change may not be so simple. Suppose you have an S corporation or a C corporation. If you liquidate the corporation to change to another form of business organization, you may have to report gains on the liquidation. In fact, gains may have to be reported both by the business and by you as owner.

Partnerships can become corporations and elect S corporation status for their first taxable year without having any intervening short taxable year as a C corporation if corporate formation is made under a state law formless conversion statute or under the check-the-box regulations mentioned earlier in this chapter.

Before changing your form of business organization it is important to review your particular situation with a tax professional. In making any change in business, consider the legal and accounting costs involved.

Tax Identification Number

For individuals on personal returns, the federal tax identification number is the taxpayer's Social Security number. For businesses, the federal tax identification number is the employer identification number (EIN). The EIN is a 9-digit number assigned to each business. Usually, the federal EIN is used for state income tax purposes. Depending on the state, there may be a separate state tax identification number.

If you are just starting your business and do not have an EIN, you can obtain one instantaneously online using an interview-style application at www.irs.gov (search “EIN online”) or by filing Form SS-4, Application for Employer Identification Number, with the IRS service center in the area in which your business is located. Application by mail takes several weeks. An SS-4 can be obtained from the IRS website at www.irs.gov or by calling a special business phone number (1-800-829-4933) or the special Tele-TIN phone number. The number for your service center is listed in the instructions to Form SS-4. If you call for a number, it is assigned immediately, after which you must send or fax a signed SS-4 within 24 hours.

If you change your business entity (e.g., from a sole proprietorship to an S corporation), you usually need to obtain a new EIN. You can determine whether you need a new EIN at www.irs.gov (search “do you need a new EIN?”).

Special Rules for Sole Proprietors

Because sole proprietors report their business income and expenses on their personal returns, they may not be required to use an EIN. Instead, they simply use their Social Security number for federal income tax reporting.

A sole proprietor must use an EIN if the business has any employees or maintains a qualified retirement plan. A sole proprietor may need an EIN to open a business bank account (it depends on the institution). An EIN can also be used in place of a Social Security number by an independent contractor for purposes of Form 1099-MISC reporting (a consideration today with concerns about identity theft). A sole proprietor should use an EIN as a way in which to build a business credit profile in order to qualify for credit without relying entirely on the owner's credit history and personal guarantee.

A single-member limited liability company, which is a disregarded entity taxed as a sole proprietorship (unless an election is made to be taxed as a corporation) for income tax purposes, must obtain an employer identification number and use the number issued to the entity (and not the EIN issued to the owner's name).