Now that you understand how files are transferred across the Web, you’re ready to explore how applets are transferred. On one hand, applets are just more files that are transferred like any other. On the other hand, what an applet can do is closely related to where it came from. This isn’t true of other data types such as HTML and GIF.

When a web browser

sees an applet tag and decides to download and

play the applet, it starts a long chain of events. Let’s say

your browser sees the following applet tag:

<applet codebase="http://metalab.unc.edu/javafaq/classes"

code="Animation.class" width="200" height="100">The web browser sets aside a rectangular area on the page 200 pixels wide and 100 pixels high. In most web browsers, this area has a fixed size and cannot be modified once created. The

appletviewerin the JDK is a notable exception.The browser opens a connection to the server specified in the

codebaseparameter, using port 80 unless another port is specified in thecodebaseURL. If there’s nocodebaseparameter, then the browser connects to the same server that served the HTML page.The browser requests the

.classfile from the web server as it requests any other file. If acodebaseis present, it is prefixed to the requested filename. Otherwise, the document base (the directory that contains the HTML page) is used. For example:GET /javafaq/classes/Animation.class HTTP 1.0

The server responds by sending a MIME header followed by a blank line (

.classfile. A properly configured server sends.classfiles with MIME typeapplication/octet-stream. For example:HTTP 1.0 200 OK Date: Mon, 10 Jun 1999 17:11:43 GMT Server: Apache/1.2.8 Content-type: application/octet-stream Content-length: 2782 Last-modified: Fri, 08 Sep 1998 21:53:55 GMT

Not all web servers are configured to send

.classfiles correctly. Some send them astext/plain,which, though technically incorrect, works in most cases.The web browser receives the data and stores it in a byte array.

The byte code verifier goes over the byte codes that have been received to make sure they don’t do anything forbidden, such as converting an integer into a pointer.

If the byte code verifier is satisfied with the bytes that were downloaded, then the raw data is converted into a Java class using the

defineClass( )andloadClass( )methods of the currentClassLoaderobject.The web browser instantiates the

Animationclass using its noargs constructor.The web browser invokes the

init( )method ofAnimation.The web browser invokes the

start( )method ofAnimation.

If the Animation class references another class,

the Java interpreter first searches for the new class in the

user’s CLASSPATH. If the class is found in

the user’s CLASSPATH, then it is created

from the .class file on the user’s hard

drive. Otherwise the web browser goes back to the site from which

this class came and downloads the .class file

for the new class. The same procedure is followed for the new class

and any other class that is downloaded from the Net. If the new class

cannot be found, a ClassNotFoundException is

thrown.

There is much FUD (fear, uncertainty, and doubt) in the press about what Java applets can and cannot do. This is not a book about Java security, but I will mention a few things that applets loaded from the network are usually prohibited from doing.

Applets cannot access arbitrary addresses in memory. Unlike the other restrictions in the list, which are enforced by the browser’s

SecurityManagerinstance, this restriction is a property of the Java language itself and the byte code verifier.Applets cannot access the local filesystem in any way. They cannot read from or write to the local filesystem nor can they find out any information about files. Therefore, they cannot find out whether a file exists or what its modification date may be.

Applets cannot launch other programs on the client. In other words, they cannot call

System.exec( )orRuntime.exec( ).Applets cannot load native libraries or define native method calls.

Applets are not allowed to use

System.getProperty( )in a way that reveals information about the user or the user’s machine, such as a username or home directory. They may useSystem.getProperty( )to find out what version of Java is in use.Applets may not define any system properties.

In Java 1.1 and later, applets may not create or manipulate any

ThreadorThreadGroupthat is not in the applet’s ownThreadGroup. They may do this in Java 1.0.Applets cannot define or use a new instance of

ClassLoader,SecurityManager,ContentHandlerFactory,SocketImplFactory, orURLStreamHandlerFactory. They must use the ones already in place.

Finally, and most importantly for this book:

An applet can only open network connections to the host from which the applet itself was downloaded.

An applet cannot listen on ports below 1,024. (Internet Explorer 5.0 doesn’t allow applets to listen on any ports.)

Even if an applet can listen on a port, it can accept incoming connections only from the host from which the applet itself was downloaded.

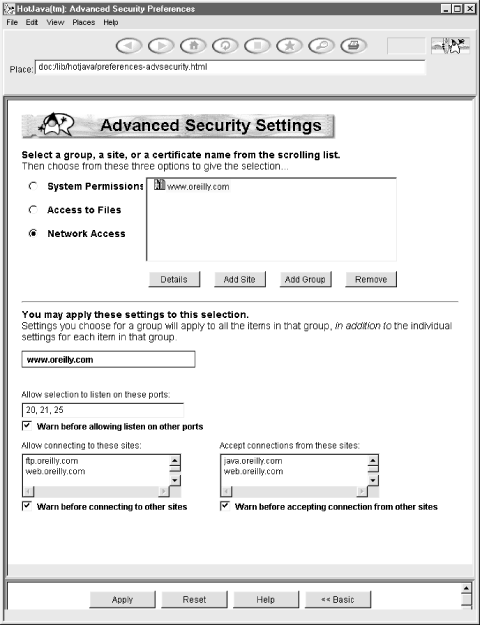

Of these 11, only the second and ninth are serious inconveniences for a significant number of applets. These restrictions can be relaxed for digitally signed applets. Figure 3.4 shows the HotJava advanced applet security preferences window that allows the user to choose exactly which privileges she does and does not want to grant to which applets. Navigator and Internet Explorer 4.0 and later have similar options. Unfortunately, all three browsers have different procedures for allowing applets to ask the user for additional permissions.

However, even if you sign your applet, you should not expect that the user will choose to allow you to open connections to arbitrary hosts. If your program cannot live with these restrictions, it should be an application instead of an applet. Java applications are just like any other sort of application: they aren’t restricted as to what they can do. If you are writing an application that will download and execute classes, you should consider carefully what restrictions you should put in place and design an appropriate security policy to implement those restrictions.