3

CURRENT APPROACHES

AND PAIN POINTS

HOW CUSTOMERS LOOK AT

TODAY’S SOLUTIONS

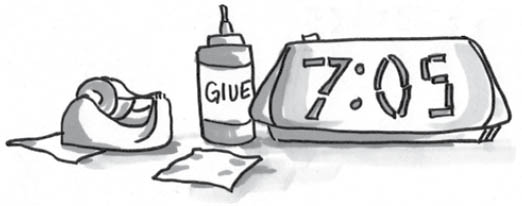

WE ONCE CAME ACROSS an individual who had made an interesting alteration to his alarm clock. He had added a drop of glue to the top of one of the buttons, creating a slight bump. The problem, as he explained, was that all of the buttons felt more or less the same. This was particularly true as he was reaching blindly above his head in the early hours of the morning after being jarred out of his sleep by the sudden onset of loud music. To make matters worse, 14 of the 15 buttons on the alarm clock would not turn off the alarm. One of those 15 buttons would temporarily quiet the alarm, but that would simply cause the fiendish clock to yet again rouse his sleeping wife 9 minutes later, by which point he had already left for the shower. This created an entirely different set of problems. Adding glue to the elusive button was this individual’s way of alleviating this unwanted morning frustration.

WE ONCE CAME ACROSS an individual who had made an interesting alteration to his alarm clock. He had added a drop of glue to the top of one of the buttons, creating a slight bump. The problem, as he explained, was that all of the buttons felt more or less the same. This was particularly true as he was reaching blindly above his head in the early hours of the morning after being jarred out of his sleep by the sudden onset of loud music. To make matters worse, 14 of the 15 buttons on the alarm clock would not turn off the alarm. One of those 15 buttons would temporarily quiet the alarm, but that would simply cause the fiendish clock to yet again rouse his sleeping wife 9 minutes later, by which point he had already left for the shower. This created an entirely different set of problems. Adding glue to the elusive button was this individual’s way of alleviating this unwanted morning frustration.

While the glue on the alarm clock may have slightly marred an otherwise stylish appliance, this workaround was far preferable to the pain point that was otherwise annoying both the clock purchaser and another important stakeholder. If only the clock maker had possessed that insight! Understanding what customers do today and how they respond to various pain points broadens the solution space for both incremental and breakthrough innovations.

IN THIS CHAPTER, YOU WILL LEARN:

![]() How to identify key stakeholders beyond the product purchaser.

How to identify key stakeholders beyond the product purchaser.

![]() When to replace and when to complement existing customer behaviors.

When to replace and when to complement existing customer behaviors.

![]() How to add value by identifying and solving customer pain points.

How to add value by identifying and solving customer pain points.

LOOKING BEYOND WHO BUYS THE PRODUCT

In many markets, such as with B2B purchases or the public sector, the buyer is not the only person who needs to be satisfied. Buyers’ decisions always reflect a careful juggling of the different priorities of multiple stakeholders who will be affected by the decision. It’s not enough, therefore, to blackbox a buyer into a single entity. A thorough understanding of how decisions are made requires an identification of key stakeholders, what they are doing, and what bothers them about the process.

Let’s look at the grocery industry. A few years back we conducted Jobs research for a client who wanted further insight into people’s decision making about what they took home from the store and why. Through the research, we noted that at least three stakeholder types would have distinct requirements in the shelf-to-table flow: the person buying the product, the person preparing the food, and the person eating the food. Certainly, there was often overlap. The person buying the food might also be the one to cook it, for instance, and/or the ultimate diner. But this varied from scenario to scenario. If we had observed only the in-store shopper, we might have assumed that price and fit into established shopping patterns were the most important jobs to satisfy. Had we focused our efforts on the meal preparer, we might have determined that ease of preparation reigned supreme. Had we simply talked to someone who just finished a meal, the level of spiciness might have been the top-of-mind insight. Looking too narrowly would have led to a new product that failed to satisfy important stakeholders.

The easiest way to make sure you are not missing key stakeholders is to create a process map from the customer’s perspective (see Figure 3-1). Throughout your research, make sure you are asking about and/or observing each step of the process and noting the specific approaches taken by the customer, starting from the time the customer begins thinking about a job to when that job is satisfied. This step-by-step approach enables you to identify key stakeholders and understand how they influence the way the customer ultimately defines her jobs.

In building out a process map, being as specific as possible will help you identify pain points. A pain point is an area where a customer experiences frustration, boredom, or inefficiency. Pain points are often fertile ground for innovation and therefore merit special attention. Additionally, process maps must also be created for particular occasions, not the average scenario. Thinking back to the grocery scenario, trying to create a process map for the broad category of “shopping for meals” would be too ambiguous. After all, a Tuesday afternoon lunch at work, a Friday night dinner for two, or a Sunday afternoon lunch with the family all result in a unique combination of levers to be pulled. Not only do the functional and emotional jobs vary in each of these situations, but the stakes, challenges, and requirements for success change as well. Designing a compromise-heavy solution that attempts to meet the needs of all these situations is likely to result in a solution that fails to satisfy anyone.

SAMPLE PROCESS MAP

Example – Dinner Preparation

Figure 3-1

INTEGRATING SOLUTIONS WITH EXISTING BEHAVIOR

Observing current stakeholder behavior affects one of the most crucial decisions you will have to make when designing a new solution—whether to complement current approaches or replace them. If the expectation is that customers will need to alter existing behaviors, it is important to accurately gauge how likely behavior change is and how rapidly it will occur. Consider Kellogg’s Breakfast Mates, which launched in the late 1990s and contained cereal, milk, and a spoon all in one package. The company was trying to alleviate pain points associated with rushed mornings while capitalizing on opportunities in the potentially lucrative breakfast-on-the-go market. Unfortunately, the product required customers to make a choice about how to alter their preconceived notions about breakfast. Were they supposed to refrigerate the product and eat chilled cereal? This ran counter to claims that the milk did not need to be refrigerated, and if they were taking the cereal on the go, the milk would warm up anyway. Did this mean that they were supposed to pour warm milk on their cereal? That also did not seem appealing. In the end, customers opted to take neither approach, and the product was soon pulled from the shelves.1

Current behaviors may seem dysfunctional, but they represent a powerful tide to swim against. Companies often find that even though they’ve identified pain points they can resolve, those pain points aren’t “painful” enough to motivate a change in behavior. Or consumers are so used to shopping on autopilot that they don’t even notice the pain points that the company has deemed important. Those working in the field of international development bump up against the stickiness of established behaviors all the time. Any fieldworker can tell you that getting people to switch the way they do things—even if it radically improves their lives—can be an uphill battle.

Promoting girls’ education in post-Taliban Afghanistan is a prime illustration of the difficulties of swimming against the norm. Afghanistan is widely associated with the Taliban and their draconian policies toward women—burkas, child brides, and no schools for girls. The invasion of Afghanistan by the United States in 2001 and its subsequent nation-building program was geared toward changing some of the more unpalatable practices toward women. The new Afghan government, supported by the United States and other international donors, made girls’ education a priority. Under the Taliban, the enrollment of girls in primary school fell from an already low 32 percent to a paltry 6 percent The goal was to get this number up.

The challenge was not in the large cities, such as Kabul, but in rural areas where attitudes toward girls’ education remained extremely conservative. In these areas, early attempts to rebuild classrooms, hire female teachers, and boost enrollment failed miserably. Foreign NGOs and the military poured millions of dollars into girls’ education and built an untold number of schools, only to find that the buildings were turned into livestock sheds and the girls remained at home. Why didn’t their efforts work?

A major obstacle to uptake was the perception that a girls’ education program was “foreign driven.” Community elders and leaders were consulted only marginally by the international actors hired to improve the Afghan educational system whose efforts—while well meaning—were largely inconsistent with societal norms. In their attempt to “do good,” they did not adequately take into consideration the beliefs, preferences, and attitudes of the people they were looking to help. The result was a roadblock on the route to improvement.

Over time, organizations realized they needed to work harder to include men and boys in their gender initiatives in order to avoid backlash and mitigate concerns that a girls’ education program was undermining their authority or status. These groups also invited elders and other leading community members to take responsibility for the initiative, even contributing land and labor toward building the schools on their own. This approach—swimming with the tide of attitudes and behaviors—was much more successful.

IDENTIFYING PAIN POINTS

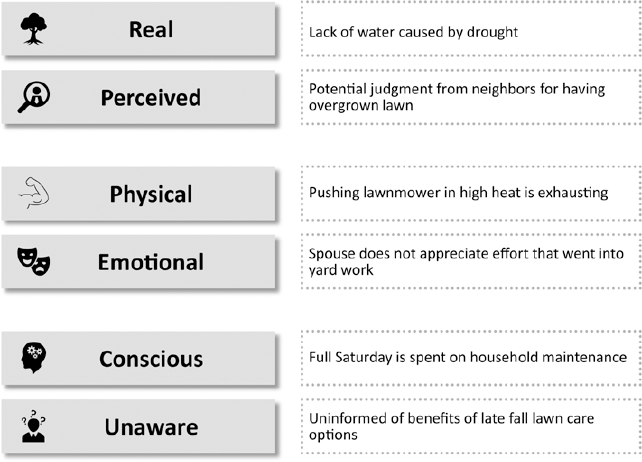

Although customers may be reluctant to part with certain current approaches, they are consistently looking to alleviate pain points. Pain points are problems that inhibit a customer’s ability to get a job done. They are things that customers find inefficient, tedious, boring, or frustrating. Consider some of the pain point pairs in maintaining a lawn (see Figure 3-2).

COMMON TYPES OF PAIN POINTS

Example – Maintaining the Lawn

Figure 3-2

While some pain points are obvious and can be quickly captured through common sense or conversations with customers, others are less apparent and are better captured through journal recordings and observations (e.g., process complexity, points of confusion or indecision, accepted workarounds). This phenomenon occurs even in the most rational-seeming environments. For example, a medical technology company we worked with interviewed dozens of surgeons to understand what was challenging about particular surgical procedures. It then hooked up heart rate monitors to those surgeons during the procedure, and the data told a very different story. Surgeons got frustrated when doing repetitive tasks, when they couldn’t do their job due to having an obstructed view of the surgical site, and in many other situations that they often took for granted as inevitable parts of conducting an operation.

Every pain point creates room for innovation. Kimberly-Clark, a global consumer goods company, observed that a number of adults suffering from incontinence were adopting compensating behaviors—from wads of toilet paper to frequent wardrobe changes—to combat a variety of physical and emotional pain points. It designed its Depend Silhouette and Real Fit Briefs to help alleviate the need for those workarounds while also solving key underlying jobs in a socially palatable way. In doing so, Kimberly-Clark captured substantial sales volume from adults who previously suffered for months or even years before buying an incontinence product.2

SOLVING FOR PAIN POINTS

One of the hardest parts about alleviating pain points is making sure you are solving for real pain points—not your personal dissatisfactions, not pain points of customers in other industries, and not artificial pain points that just happen to be the counterpoints to your product’s newest features. One way to help do this is to quantitatively assess the validity of your identified pain points in a large sample. Even though real customers may have pointed out several pain points, it does not necessarily mean that the larger population shares those same issues. Using a quantitative survey, you can map pain points to particular customer segments, ultimately ensuring that you are solving pain points for customers you actually wish to target.

You can also use such surveys to identify priorities among pain points, potentially through a technique such as conjoint analysis. This approach calls for having customers weigh trade-offs. Would you prefer a laptop that has two hours more battery life or that weighs half a pound less? Would you prefer that its keyboard be more resonant or that it be five millimeters thinner? Making trade-offs concrete helps to get at customers’ true preferences—the ones you will ultimately see reflected in their buying behavior.

THIS CHAPTER IN PRACTICE—ADDRESSING PAIN POINTS WITH THE CUSTOMER IN MIND

A few years back, we worked with a company that happened to be shifting to a new file management system. Objectively, the new system was a million times better than the system being replaced. It offered increased storage capacity, improved search functions, easier file sharing, and a host of other new features. But in bringing in these new benefits, it eliminated the folder-based system that the company’s employees were used to. In fairness, the folder system made certain recurring tasks easier for the employees. And, at the end of the day, the company’s employees simply had more faith that they would be able to find what they were looking for in folders—even if it took some digging—than if the information was somehow sorted by these intangible meta tags that had been described to them. As the transition progressed, some employees moved to the new system, others continued using the old system, and a small subset created folder-based workarounds in the new system. Anyone looking for a file needed to run multiple searches that looked through both systems. As you might imagine, the resulting mess was very costly and time-consuming. One of the company’s senior executives created a weekly meeting called Sharepoint: The Surge—named after a strategy from the war in Iraq—to resolve all of the complications that were arising. Those who were designing the new system could have developed an alternative that kept the familiar folder-based storage mechanisms. Instead, they doubled down on trying to convince the employees that the approach they knew and loved was inferior. That team learned the hard way that having an objectively better product is meaningless if it cannot solve pain points in a way that aligns with popular current approaches.

CHAPTER SUMMARY

Making a “better” product is the easy part of innovation. The hard part is ensuring that your new product is better for the right people in the right ways. New solutions need to account for the needs of multiple stakeholders, each of whom may have different expectations. At the same time, new offerings need to solve pain points in a way that fits with ingrained behaviors. Understand what’s wrong with the status quo, but be wary of engaging in a headlong battle against habit.

The product purchaser may be just one of several stakeholders who will need to be satisfied by your offering. Consider whether other end users or key decision makers will need to be satisfied along the way.

Making a process map—a graphical depiction of each step of the customer’s journey from deciding to buy a product to disposing of it—can help identify additional stakeholders, and it can be a good way to spot pain points that are making customers unhappy.

Customers may be willing to change some behaviors to use your product, but not always. Make sure you understand which current approaches will be leveraged and which will be replaced. If you expect customers to change their behavior, remember that such change often occurs slowly.

Customers are routinely looking for new solutions that help them alleviate pain points—the issues that get in the way of satisfying a job to be done. Look beyond those pain points that are obvious to also consider those that are emotional or about which customers are unaware.

Consider trade-offs. It may not be feasible to solve for all pain points at once, so force customers to state priorities through suggesting clear choices.