8

ESTABLISH

OBJECTIVES

JUST A FEW YEARS ago, there was a lot of buzz in the digital health space, but no one could point to a company actually making profits in the area of health wearables. Companies weren’t sure where the money would be, and they debated whether to go after the really sick patients, the well but worried consumers, or the active fitness enthusiasts. Early companies like BodyMedia took a muddled approach and tried to please everyone. When its business suffered as a result, BodyMedia was eventually acquired by Jawbone, largely for its patent portfolio.

JUST A FEW YEARS ago, there was a lot of buzz in the digital health space, but no one could point to a company actually making profits in the area of health wearables. Companies weren’t sure where the money would be, and they debated whether to go after the really sick patients, the well but worried consumers, or the active fitness enthusiasts. Early companies like BodyMedia took a muddled approach and tried to please everyone. When its business suffered as a result, BodyMedia was eventually acquired by Jawbone, largely for its patent portfolio.

Compare the story of BodyMedia to that of Fitbit. Fitbit created a clear strategy from the outset, focusing on a relatively narrow segment of the consumer market: casual exercisers looking to be more active. Rather than looking to radically change the way patients are cared for or force everyone to become an athlete, Fitbit honed in on a very simple proposition—using your everyday activities to improve your overall health. The company keyed in on one overarching job related to easy fitness and offered just enough of a solution to get consumers what they were looking for. It offered a way to track your existing activity levels—in terms that you could both understand and relate to any diet plans you might want to integrate—as well as to set and reach goals for being just a little bit healthier. Despite a very simple model, Fitbit used its targeted strategy to excel. Since launching its first generation of devices in 2009, Fitbit has sold roughly 30 million fitness devices, and it has a market capitalization of nearly $8 billion.1 Even as the company and its competitors continue to evolve, Fitbit is sticking with a simpler value proposition. In explaining why Fitbit devices continue to outsell other wearables, the company’s CEO, James Park, explained that competing devices (such as the Apple Watch) simply try to do too much. Fitbit sold over a million of its new Blaze smartwatches and over a million of its new Alta fitness trackers in just their first month of availability.2

IN THIS CHAPTER, YOU WILL LEARN:

![]() What questions you need to answer to set a strategic course.

What questions you need to answer to set a strategic course.

![]() How to craft project mandates that help achieve your strategic objectives.

How to craft project mandates that help achieve your strategic objectives.

![]() How to identify uncertainties that your project will need to address.

How to identify uncertainties that your project will need to address.

SETTING A STRATEGIC COURSE

All organizations—from start-ups to established businesses—need a strategy. While it may seem obvious that a new business needs a strategy so that it can get off the ground, the need for a well-defined strategy is even greater for established businesses. They have to consider how they will fend off potential disruptors, how they will stay ahead of existing competitors, and how they will balance optimizing the core business with growing in adjacencies. Deeper than the typical high-level mission statement (“Our goal is to be the market leader. . . .”), your strategy tells you precisely how your organization is going to outperform the competition. Influenced by Procter & Gamble’s A. G. Lafley and the University of Toronto’s Roger Martin, our thinking on how to develop a winning strategy requires making five discrete choices (see Figure 8-1).3 Ultimately, your strategy should be an explanation of how your choices meld together to form a concrete plan of action.

FIVE D’S OF SUCCESSFUL STRATEGY

Figure 8-1

Too often, companies fail to get specific in how they answer these questions, or they agree on the easy answers without pushing themselves to go deeper. Successful strategies are ones that challenge conventional wisdom, allowing you to do things that your competitors haven’t yet thought to do.

A good strategy matters not just for the overall organization but for individual projects too. With a clearly defined strategic objective, teams using the Jobs Roadmap can ensure that their efforts support well-articulated aims. A major virtue of the Jobs approach is that it is expansive and yields a fully rounded view of latent demand; however, that virtue can turn into a danger of boiling the ocean if there isn’t also a way to cleanly prioritize interest areas and determine which insights are most worthy of turning into specific opportunities. Setting strategic objectives, therefore, isn’t just for strategy departments; it is for any team looking to use the Jobs approach to produce innovative ideas.

The first step in creating a strategy is defining what it means to win. Often this is expressed in the form of a quantitative target (e.g., growing revenue from new products by 20 percent over five years), but it can also be qualitative (e.g., developing a self-serve business model that will allow us to fend off new low-cost entrants). As you define what it means to win, you should also be asking yourself why you have come up with that objective. Why are you pursuing the path you chose? What would be different if you chose a different target or a different time frame? Businesses often announce wild aspirations simply because they sound good (20 percent growth by 2020!) without spending significant time thinking about whether they’ve chosen the right goals and how their goals can be achieved. As you answer the questions in our model, revisit your initial definition of a win to better understand whether your objectives are attainable and what resources you will need to devote to achieving your goals. And, by all means, never confuse a goal with a strategy—a goal is useful because it will impact strategic choices, but it tells the organization very little about what to do or how to make difficult trade-off decisions.

DECIDE HOW AND WITH WHOM YOU WILL WIN

DIMENSIONS OF CHOICE

Figure 8-2

The second step in crafting a strategy is deciding how and with whom you will win. Generally this involves making choices along three dimensions (see Figure 8-2). On one axis is your familiarity with the product or service you will be selling. Is this something you’ve made before, or are you launching into a completely new class of products? On the second axis is your familiarity with the customer you’ll be serving. Are you targeting a new customer type or geography, or is the customer similar to ones you’ve served in the past? On the third axis is business model familiarity. Are you rethinking the way you operate, such as by lowering your capital needs, getting closer to customers, or adding an ecosystem of complementary services? These business model imperatives can impact both product and customer selection. As you stray farther from the core along any of these three dimensions, you’re increasing both your growth potential and your risk. Keep in mind, however, that that risk compounds as you move farther from the core along multiple dimensions. There can be great opportunity in those newer fields, but do not presume omniscience as you might in your core business.

Over time, expanding what’s considered core is an essential part of growth. While companies can muddle along for a while by copying their competitors, that’s not a strategy that will result in any kind of long-term success. That’s what Atlas Comics was doing in the 1950s. It tried imitating the concepts that seemed promising from TV and movies at the time, such as Westerns and war dramas. The company failed to launch any breakout hits, but it managed to survive by getting comics out quickly and cheaply. When the organization rebranded as Marvel in the 1960s, it tried a different strategy. Its first step was to take a familiar product—superhero comics—and make them popular again, this time reaching new customers. It then innovated that product; Marvel’s Fantastic Four was one of the first to make real-world struggles and adult issues a part of comic book culture, allowing comics to appeal to new customers—adults as well as the traditional younger readers. Marvel continued to add characters with soaring popularity, such as Spider-Man, Hulk, and Wolverine.

In the decades that followed, Marvel experienced pockets of phenomenal success, but it also faced deep competition from rival DC Comics. In an effort to shrug off its financial troubles and keep heroes relevant, Marvel took its core assets—its tried-and-true stories and characters—and brought them into totally new products. Marvel’s new movies gave the company’s characters mass appeal across customer types. Its 2012 blockbuster The Avengers sits as one of the five highest-grossing films of all time, bringing in over $1.5 billion worldwide; it also helped to expose Marvel to still more customers, such as Chinese audiences who hadn’t grown up with these characters. It also added more leading female characters over time, such as Jessica Jones, to bring comics beyond their traditional male reader domain. Most recently, Marvel has made a push to try new business models as well. Building on the success of its Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. TV series on ABC, for example, Marvel partnered with Netflix to offer Daredevil as exclusive programming for Netflix subscribers. Marvel also experimented with an alternative model for selling comics with its Marvel Digital Unlimited app, which offers readers mobile access to comics on a monthly or yearly subscription basis. While Marvel has seen enormous success by expanding into adjacencies along all three dimensions of growth, it’s important to remember that its success was premised on its ability to leverage its core stories and characters—its most valuable assets.

The third step for honing your strategy is determining your competitive advantages. This involves identifying the strengths that allow you to expand beyond the core, as well as the assets and tactics that you can use to outperform any competitors who are already playing (or may choose to start playing) in your newly chosen arena. In the ideal scenario, the advantages you leverage will also act as signals to potential rivals to stay out of your new markets. Your advantages will help to determine where to focus, so there may be iteration between steps two and three of this process.

The fourth step for creating a strategy is about defeating specific and articulable challenges. It’s folly to assume that just because you set a goal you can achieve it. A good strategy maps out the challenges you are likely to face and the uncertainties you need to resolve, articulating a plan for how risks can be reduced and how obstacles can be overcome. We recently talked to Trang Nguyen, the cofounder of Tipsy Art, which is popularizing painting as an evening social event in Vietnam.4

While she knew that she could satisfy some of the same jobs as a U.S.-based analogue of this business, called Paint Nite, she also recognized that Hanoi and Boston are completely different markets. For example, she discovered early on that alcohol was a much less significant part of the equation in Vietnam. Participants in many of the early sessions often just discarded their free drinks. The Tipsy Art team quickly restructured around coffee shops, which are much more of a focal point in Vietnamese culture. In addition to increasing demand, this also allowed the business to reduce its drink costs. Even now, the team continues to keep a clear vision of the challenges that will need to be addressed as the business grows, including how to build relationships that will be hard for competitors to copy, how to achieve scale in a business that relies so much on relationships and experiences, and how to ensure that the model is sustainable over the long term even if interest in introductory painting workshops begins to wane.

The fifth step in crafting a strategy involves developing growth options and the capabilities to move forward. This step focuses heavily on the “how” of strategy. What competencies do you need to develop in order to gather customer insights, build a culture of innovation, or manage a new business? Your strategy should articulate the institutional capabilities that you will build or strengthen in order to achieve your underlying objectives. At the same time, your strategy should allow for an ability to adapt as uncertainties about the future become clear. This means ensuring early on that the ability to pivot is built into your long-term plans. When a major change or event causes you to shift direction, you should be able to choose a different road, without having to backtrack or blaze an uncharted path through the woods. This is not to be confused with panic! An ability to adapt does not equate to abandoning your chosen course because a new venture proves challenging. Rather, a good strategy allows you to transition to alternative routes when certain predefined circumstances come to pass. You will have already articulated several options and will have a view as to how many of those options remain open to you.

ALIGNING YOUR PROJECT TO YOUR STRATEGY

Once you have a strategy in place, you will need to decide on the scope of the solution space. We often start by making quick yes/maybe/no decisions with some of our initial ideas to sort them into three buckets: the ideal, the imaginable, and the inconceivable.5

While we don’t want to get attached to any solution at this stage—or even consider that we understand the full spectrum of possible solutions—sorting some early ideas can be a helpful way to understand your organization’s boundaries. Are there common characteristics among all of the ideas that are inconceivable? Perhaps they require infrastructure that the organization would never invest in or a change in business model that wouldn’t pass muster with regulators. There might also be similarities among the ideal options. Maybe a good number of them leverage a technology that the company has patented. While you don’t want to focus too heavily on the ideas you’ve already come up with before doing any research, having a general idea of what’s completely out of scope will help you focus your human and financial resources as you move forward. This exercise also allows the passionate advocates of ideas to get them on the table at the outset, so that the concepts don’t keep coming up surreptitiously as you move through the process.

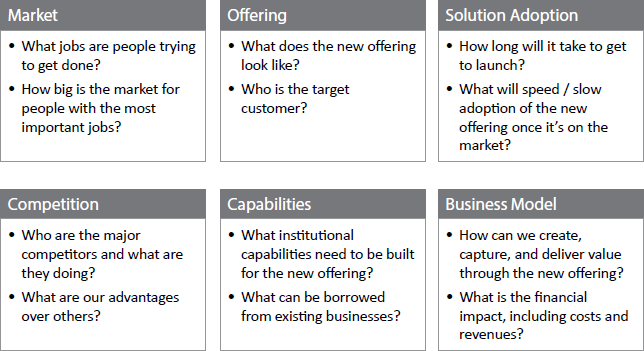

While the next chapter discusses how to construct your research plan in more detail, it’s useful at this stage to start thinking about the questions your project will answer. One option is to create a skeleton business plan without any data or conclusions (see Figure 8-3). That is to say, it can be useful to identify the questions you will need to answer without actually trying to answer them at this stage. This means figuring out all the things you will need to prove to the higher-ups in order to get approval for your new solution. In doing so, you will be able to make preliminary hypotheses about what types of research you will need to conduct, how long it will take to answer the key unknowns, and what level of resources you will need to devote—in terms of time, people, and money—to fill in all of the pieces of your final recommendation.

Figure 8-3

THIS CHAPTER IN PRACTICE—MATCHING PLANNING TO STRATEGY

When we worked with a medical device company a while back, a cross-functional core team had been formed to help advise the company’s leadership team on new business opportunities. With some guidance, the team was able to create a compelling strategy that addressed the Five D’s. With respect to defining what it meant to win, the company wanted to introduce a new service offering that would have positive operating income within two years and would help protect the company as its product lines became commoditized. In terms of deciding where and with whom it would win, the company was going to target U.S.-based medical facilities that were already using its devices to treat a certain class of chronic patients. For its competitive advantages, the company was able to generate a long list of reasons it could succeed, including its deep relationships with procurement personnel at the target facilities and access to proprietary data. The next step was to map the specific challenges the company would need to defeat, such as finding short-term sources of revenue while they put in place the mechanisms to serve their “end game” customers. Finally, the team developed a list of the capabilities they would need to succeed.

With a strategy in place, the team developed a plan for conducting primary and secondary research. The goal was to develop three models, put them through a competency assessment, then choose a single model to build into a full business plan to present to the leadership team. We plotted out the major questions that needed to be answered to reach that goal, including how large the market was for various types of solutions and whether partners could be used to fill in missing competencies. The core team’s early ideas were sorted into three categories, recognizing that there was a distinct advantage in designing a solution around a type of data that the company could access but that would be costly for others to access.

After roughly five months of research and strategizing, we came up with a solution that would help move the company into a hybrid model that would create new service-based revenue streams while opening the door to new pricing models for its products. The solution also created an opportunity to capitalize on several emerging health care trends, such as health insurers paying hospitals for medical outcomes rather than for individual services rendered. By focusing on key tenets around patient empowerment and improving the quality and economics of care, the solution was also easy to market to potential customers.

CHAPTER SUMMARY

Fuzzy objectives and a lack of communication can be major impediments to launching a new offering. The solution starts at the top. Leaders need to create a concrete strategy that answers specific questions—how winning is defined, which markets to target, what strengths can be leveraged, what challenges need to be overcome, and what capabilities need to be built in order to succeed. Once that strategy is in place, the teams charged with creating new solutions can decide which questions will need to be resolved and set boundaries on how broad the solution space can be. By ensuring that each step communicates clear objectives and priorities, project teams can help avoid the failures that result from basic misalignment.

Companies need high-level strategies so that they can organize their activities and prioritize how they spend their resources. Strategic objectives are equally useful at the team level, as they provide guidance on which opportunities are most worth pursuing.

Setting a strategic course requires answering fundamental questions about what counts as a win, which markets will be pursued, what strengths and challenges will affect an ability to win, and what capabilities need to be developed.

Project teams can ensure that their work coincides with the answers they need to give to leadership by creating skeleton business plans that identify major uncertainties. Teams should give some thought to which customer types they will target, what the offering will look like, how fast new solutions might be adopted, who the competition might be, what capabilities they’ll need to develop, and what high-level business model archetypes make the most sense.

Teams can also ensure that they maintain a reasonable project scope by sorting initial ideas into three categories—the ideal, the imaginable, and the inconceivable—and understanding the characteristics that result in an idea being placed in a particular bucket.