CHAPTER 6

Engaging in a Joint Venture: The Choices

§ 6.1 INTRODUCTION

p. 490. Insert the following new subsection at the end of this section:

(a) Impact of the 2017 Tax Act (Pub. L. No. 115-97) of Choice of Entity and Partnership Taxation

Although the core infrastructure of Subchapter K was left in place by the 2017 Tax Act (Pub. L. No. 115-97), there are significant implications on the choice of entity for business as well as compensation policy. First, Congress lowered the corporate income tax rate to 21 percent, which is a 40 percent decrease from the 35 percent top rate previously in effect. Accordingly, although the corporate rate is now significantly lower than the highest individual marginal rates that apply to pass-through businesses, there is still remaining a double tax in the corporate structure.

Nevertheless, even with the double tax, it may be an attractive structure if business is willing to leave the earnings in the corporation to compound at the preferential rates by being taxed at 21 percent rather than distribute its earnings to its shareholders (or otherwise compensate them). Other issues arise such as the case where the shareholders also are employed by the company and are to be receiving reasonable compensation; there are also employment tax issues and tax-deferred benefits issues to be considered. In any event, it is important to examine how the new 20 percent deduction of qualified business income (§ 199A) will apply to the particular business strategy.

§ 6.2 LLC

(b) Comparison with Other Business Entities

p. 449. Insert the following new subparagraph at the end of this subsection:

(vi) “Philanthropic” LLCs vs. Public Charities and Private Foundations. The phrase “philanthropic or charitable LLC” is an informal term without a legal definition. It follows the Chan Zuckerberg announcement about their Initiative. See subsection 6.8(c).

Forgoing Tax Exemption. Public charities and private foundations are tax-exempt organizations, whereas LLCs act as pass-through entities (as to profits, losses, gains, etc.) and provide limited liability to their members. While public charities typically fundraise from a broad section of the general public, private foundations are typically funded by a single family or corporation. All private foundation and public charity expenditures must be made for a charitable purpose. This is in contrast to an LLC, whose members may benefit from a charitable contribution deduction only when the LLC contributes to a charity, and not when the members contribute funds to the LLC.

Private foundations, in contrast to public charities and LLCs, are required to make annual distributions of 5 percent of their prior year's average net investment assets, that is, minimum investment return. There are further limits as to the income tax deduction for contributions to private foundations, in addition to a 2 percent tax on its net investment income. An LLC, on the other hand, has no requirement to make a minimum distribution and is not required to publicly disclose information regarding its activities or the compensation of its highest-paid officers. However, private foundations and public charities are required to make such disclosures on their IRS Forms 990-PF and 990, respectively. Finally, one of the major concerns in using an LLC is that the members will be taxed in the event that the LLC generates net income and will only receive a charitable contribution deduction in the year the LLC actually makes the contribution to a charity.

(c) Exempt Organizations Wholly Owning Other Entities

(ii) Wholly Owned S Corporation p. 500. Insert the following at the end of footnote 53:

Income from an S Corporation is per se UBTI. Accordingly, an S corporation should only be considered as an entity in a joint venture structure if the net income would be treated as UBTI to the charity absent such a rule.

(d) Private Foundations as Members of LLCs

p. 505. Insert the following at the end of this subsection:

§ 6.3 USE OF A FOR-PROFIT SUBSIDIARY AS PARTICIPANT IN A JOINT VENTURE (REVISED)

(b) Requirement for Subsidiary to Be a Separate Legal Entity

p. 516. Insert the following new subsections (iv), (v), (vi), and (vii) before paragraph (c):

(iv) In September 2015, National Geographic Society (“NGS”) formed a joint venture with 21st Century Fox called National Geographic Partners, a for-profit media joint venture. In this new venture, Fox has paid $725 million to National Geographic for the contribution of the charity's assets, including its television channels, related digital and social media platforms, as well as travel, location-based entertainment, catalog, licensing, and e-commerce businesses. National Geographic's purpose is to allow it to focus on its fundamental exempt goals of increasing knowledge through science, exploration, and research as to which its endowment will increase to approximately $1 billion. National Geographic received a 27 percent interest in the venture (which will be held by a second-tier, for-profit subsidiary). Fox received a 73 percent interest; in addition to its cash investment, it will provide expertise in global media platforms. There will be an eight-member board of directors, which will have equal representation from the parties; the chair of the board will alternate annually, the initial chair having been chosen by National Geographic. It is understood that the charity obtained opinions of counsel regarding the valuation of the assets that transferred as well as the tax aspects of the underlying transaction.

(v) The IRS issued a favorable ruling112.2 in a case where a § 501(c)(3) private school formed a taxable for-profit subsidiary to hold intellectual property. The subsidiary developed software for online educational programs and granted the free license to the parent but could also license the IP to other schools for a royalty. The key issue was whether there was any attribution of the subsidiary to the parent following the Moline Properties analysis. The IRS concluded that the structure did not jeopardize the parent's § 501(c)(3) status and ruled that the income from the activity was not unrelated business income. The facts indicate that although the parent owned 100 percent of the taxable subsidiary, it did not control the day-to-day affairs of the subsidiary. It respected the corporate formalities. The subsidiary intended to license the software to unrelated schools; accordingly, the subsidiary was respected as separate from the parent. Neither the activities nor the income of the subsidiary was attributed to the parent.

The IRS determined that the subsidiary was not a mere instrumentality of the institution because the majority of its governing board is independent and does not have a relationship with the school. Moreover, the institution did not actively participate in the day-to-day affairs of the for-profit organization. The IRS also based its ruling on basic factors such as separate bank accounts, financial records, facilities, and telephone listings. Thus, the IRS concluded that the tax-exempt status of the school would not be adversely affected by its ownership of the for-profit.

We note that although a discussion of the use of equity-based compensation was not included in the analysis or holding of the ruling, it would not affect the institution since the two organizations were determined to be separate entities for tax purposes, and therefore the for-profit would not be subject to § 4958 of the Code regarding excess benefit transactions, because § 4958 is applicable only to organizations described in §§ 501(c)(3) and (c)(4) of the Code.

The IRS also ruled on the UBIT implications of the school's ownership of the for-profit. The IRS determined that since the for-profit's activities could not be attributed to the institution, the subsidiary's gross income would not be UBIT to the institution under § 512(a)(1) of the Code.112.3

Section 512(b)(13) provides that if a controlling entity receives or accrues a specified payment from another entity it controls, the payment would be included in the UBIT of the parent to the extent it reduces the net unrelated income of the controlled entity. However, dividend income is not a specified payment and therefore is not subject to UBIT. Thus, any dividends paid by the for-profit to the institution would not be subject to UBIT.

(vi) Other Rulings of Note. PLR 201644019. Although the IRS will not issue rulings on joint ventures per se,112.4 it will issue rulings as to whether particular activities are in furtherance of exempt purposes. As the fact pattern of PLR 201644019 demonstrates, counsel can carefully structure a ruling request that does not focus on a joint venture per se, but on other issues, including future charitable activities and use of for-profit subsidiaries to block attribution of for-profit activities to the § 501(c)(3).

In the ruling, a Charity's wholly owned for-profit subsidiary (“Subsidiary”) formed an LLC (Partnership) with an unrelated party (X). Charity sold certain assets to Partnership for cash to use to expand its charitable/educational programs. X also indirectly transferred assets to Partnership in exchange for membership interests held through a for-profit subsidiary of X.

Subsidiary also transferred assets to Partnership through two disregarded entities in exchange for Partnership interests. The Charity and Partnership entered into a trademark license agreement whereby the Partnership would pay royalties for the use of the Charity's trademarks, domain names, and social media handles. Of particular importance was Charity's representation that it would not directly or actively participate in the day-to-day management of Subsidiary or any subsidiary or affiliate of Subsidiary, including the Partnership.112.5

The IRS ruled that:

- Charity's use of proceeds from the asset sale would further its § 501(c)(3) missions and purposes.

- The sale of assets would not generate UBI because the sale was not a business regularly carried on within § 512(a) but rather was a one-time sale.

- Payments by Partnership to Charity under the trademark license agreement constituted royalties under § 512(b)(2).

- Subsidiary would be respected as an entity separate from Charity as it satisfied the business activity requirement of Moline Properties. As a result, Subsidiary's involvement in the Partnership would not be attributed to Charity.112.6

(vii) The IRS recently issued a private letter ruling that raises concerns as to whether the traditional structural model is being reexamined and may be troublesome for the EO community.112.9 In the ruling, a § 501(c)(3) hospital system parent requested rulings that certain political activities, including operating a PAC, conducted by its wholly owned for-profit corporation would not adversely affect the parent's 501(c) status. In addition, the parent requested rulings related to a shared services agreement between the parent and the for-profit corporation, the provision of the parent's employee mailing list to the for-profit, and board and officers' overlaps pertaining to the parent and for-profit with regard to political activities.

The § 501(c)(3) parent also requested the IRS to rule that:112.10

- The operation of a PAC will not constitute participation or intervention in a political campaign by the parent.

- Its provision of services and other resources (facilities and equipment) to the subsidiary and PAC pursuant to a shared services and facilities agreement, in which the parent was reimbursed for costs, will not constitute participation or intervention in a political campaign by the parent.

- The shared services and facilities agreement will not cause the parent to be operated for private benefit or private inurement.

The parent was the sole shareholder of the subsidiary, which owned interests in two joint ventures and was sole member of an LLC that provides management services to the hospital system. The parent may elect all of the subsidiary's directors and may remove any director with or without cause. The parent may elect or appoint the subsidiary's officers and assistant officers or permit the directors of the subsidiary to do so; it is important to note that the subsidiary does not have any employees who are not also employees of the parent.112.11

The parent planned to form a section 527 PAC and select the PAC's board of directors, which, in turn, will select the PAC's officers; the individuals may serve concurrently as officers or directors of the subsidiary or employees of the parent; the PAC will not have its own employees. The subsidiary and PAC will solicit voluntary contributions to the PAC from employees of the parent, the subsidiary, and joint ventures/LLC in the system. In addition, the parent's employees will engage in fundraising services pursuant to the shared services agreement on behalf of the subsidiary. The parent will also provide a mailing list (names, titles, etc.) of its employees to be used by the subsidiary/PAC to comply with federal and state campaign finance laws.

The IRS held that providing the parent employee information to the subsidiary solely to allow the subsidiary/PAC to comply with campaign finance laws so that the PAC may make expenditures to support or oppose candidates for public office is political intervention; reimbursement at fair market value is not enough.

Secondly, the parent's employees are being used to provide services to the subsidiary/PAC. And despite representations and agreement terms, there are no “guardrails or limitations” with respect to services that might be inconsistent with the parent's exempt purposes. Furthermore, there is no demonstration that employees should be treated as employees of the subsidiary rather than the parent for this purpose since the parent's employees will be soliciting contributions to the PAC at the parent's offices during regular business hours, making the activities inseparable from the parent's own operations. Finally, reimbursement at cost or fair market value is not enough to satisfy the separateness standard.

Accordingly, the mailing list and shared services agreement, in this context, result in political intervention and impermissible private benefit to the subsidiary.

- The subsidiary's operation of the PAC will constitute participation or intervention in a political campaign by the § 501(c)(3) parent.

- The parent's provision of services and other resources (facilities and equipment) to the subsidiary and PAC pursuant to the services agreement will constitute participation or intervention in a political campaign by the parent.

- The services and facilities agreement will cause the parent to be operated for the benefit of private interests (and will not further an exemption purpose).112.12

Some leading commentators have argued that this decision is a reversal of prior IRS guidance in the area, at least where IRS has approved an exempt parent creating a (c)(4) subsidiary. The decision may have implications beyond political activities:

- There are similar governance overlap issues without safeguards that may arise and demonstrate that the parent § 501(c)(3) is arguably controlling the potentially nonexempt activities in question; thus, the activities may be attributed to the exempt parent (e.g., lobbying, unrelated trade or business).

- This may be the case even if there is no shared services agreement or mailing list rental.

When using a shared services agreement in any context involving an exempt organization and a related taxable entity, the practitioner needs to look beyond whether the exempt entity is being treated fairly and at fair market value (i.e., review the terms relative to governance overlap and control).

(d) UBIT Implications Applicable to the Use of a Subsidiary

(i) General Rule p. 518. Add the following to the end of footnote 119:

See PLR 20153018 (Oct. 24, 2014), § 6.3(b)(iv), supra.

p. 525. Add the following new subparagraph:

(iv) Use of C Corporation Blocker.151.1 It is often beneficial to use a C corporation as a blocker that can be inserted between an exempt organization and the potentially damaging activity to “block” the attribution of the activity to the exempt organization. This is especially useful for blocking excess UBI, as well as political activity, excess lobbying, or conduct of an activity that would jeopardize exemption if conducted directly by the exempt organization. This is so because under section 512(c) and the partnership flow-through of income (see Chapter 2), a partnership's trade or business regularly carried on would be unrelated trade or business with respect to the exempt organization partner. See in this regard the potential of foreign withholding tax.

The C corporation blocker has been respected in PLR 200405016, PLR 200518081, and PLR 201409009. However, the C corporation blocker has not been respected in PLR 200842050.

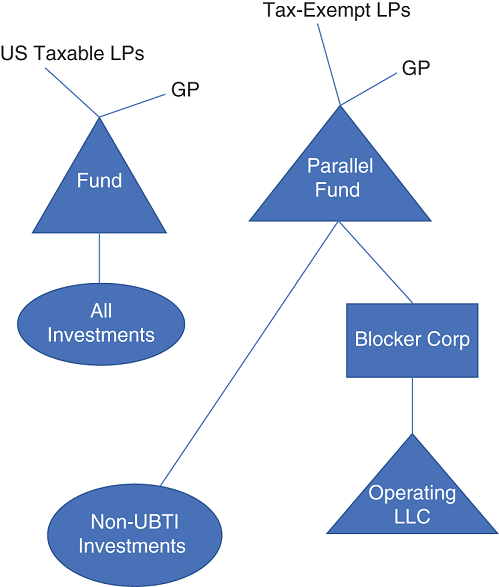

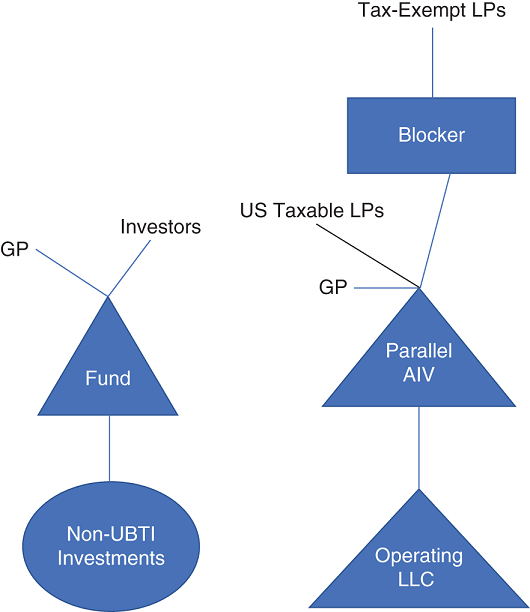

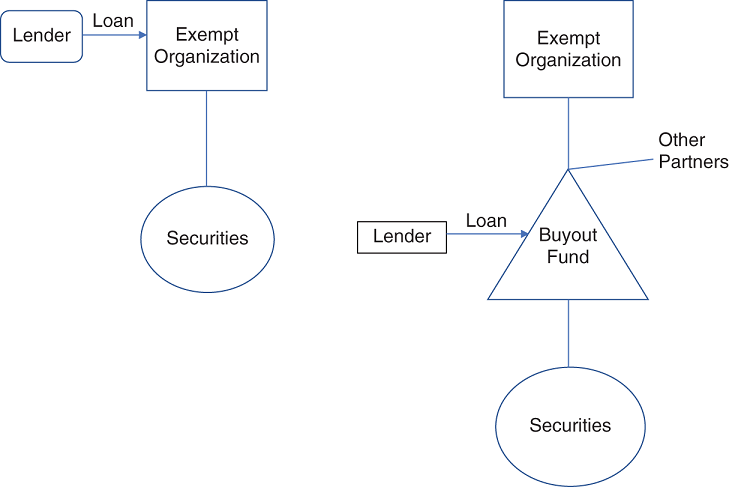

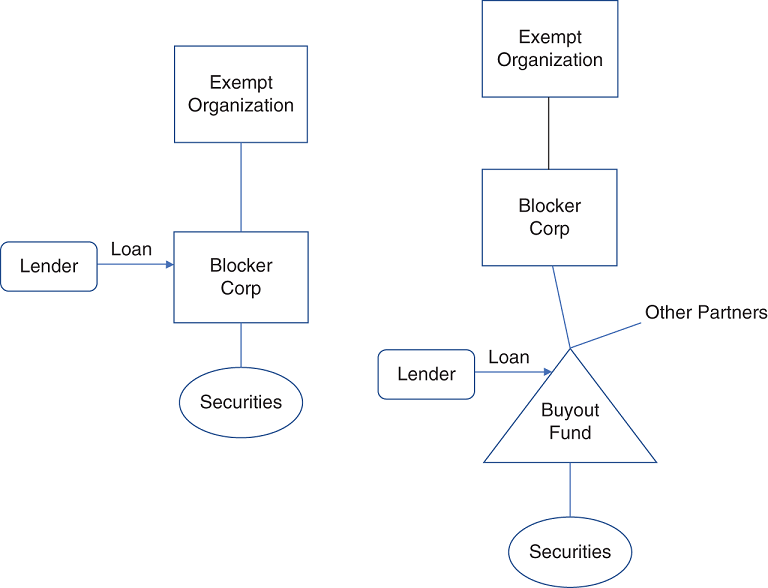

The following five diagrams prepared by Amanda Nussbaum, tax partner at Proskauer, were presented in Georgetown University Law School class, Special Topics in Exempt Organizations (Spring 2021); they illustrate how a C corporation could be beneficial in blocking UBTI. (There is presently a 21 percent tax on net UBIT revenue. See Sections 8.7 and 14.6, Scenario 4.)

Structure One: Basic Investments in Flow-Throughs Basic Structure to Block UBTI

- UBTI flows to Blocker Corp.

- If Blocker Corp is a U.S. entity, Blocker Corp pays corporate tax on all income allocated by Operating LLC.

- Only Blocker Corp has to file a U.S. tax return.

- Unless Fund can sell stock of Blocker Corp, exit triggers 21 percent tax on gains.

- Tax-inefficient for GP and U.S. taxable investors, who would have paid only 20 percent tax.

- Also tax-inefficient for tax-exempt investors because gains on exit (unlike operating income) generally would not have been subject to U.S. tax.

Structure Two

Alternative Structure: Investment Directly and Indirectly Through Blocker Corp

- Eliminates the inefficiency for U.S. taxable investors and the GP.

Structure Three

Alternative Structure: Parallel Fund for Electing Tax-Exempt Investors

- Blocker pays corporate tax on LLC income allocations and files returns.

- Tax-efficient for U.S. taxable investors. May be tax-efficient for the GP if it is able to receive its carried interest through a partnership below the blocker corporation.

- Blocker incurs 21 percent tax on asset sale.

- Tax-inefficient for tax-exempt investors, unless stock of blocker can be sold (which would only be possible if the parallel fund sets up a separate blocker for each operating partnership investment).

- No ability for tax-exempts to elect into blockers on a deal-by-deal basis (unless the parallel fund sets up a separate blocker for each operating partnership investment).

Structure Four

Parallel AIV

- Blocker pays corporate tax on LLC income allocations and files returns.

- Tax-efficient for U.S. taxable investors and GP.

- Blocker incurs 21 percent tax on asset sale.

- Tax-inefficient for tax-exempt investors, unless stock of blocker can be sold.

Structure Five

Unrelated Debt-Financed Income (§ 514(c)(1): “UDFI” – Flow-Through Treatment)

- UDFI flows through partnerships. It doesn't matter how many partnerships there are, whether they are U.S. or non-U.S., or what level the debt is at.151.2

UDFI—Blockers

- Corporations block UDFI.

UDFI—REIT Structures

- REIT structures are often used to block UDFI/UBTI.

- These structures are ineffective for pension trusts that hold 10 percent of a pension-held REIT.

§ 6.5 PRIVATE FOUNDATIONS AND PROGRAM-RELATED INVESTMENTS

(a) Program-Related Investments

p. 536. Insert the following after the first full paragraph on this page:

A private foundation may make an investment that meets the PRI requirements; however, in the event that it takes the form of an equity investment in a functionally related business, such as an LLC with a for-profit member, it may nevertheless need to meet Rev. Rul. 2004-51. Otherwise, the unrelated business income rules could apply to the foundation's share of profits. See p. 380 and Section 10.4. The concern is raised because Rev. Rul. 2004-51 does not provide clarity on these issues. In fact, the IRS may conclude that the for-profit's control over the venture could convert an otherwise related activity into an unrelated activity, causing the exempt partner to be liable for unrelated business income tax.

p. 536. Delete the second full paragraph on this page and replace with the following:

Though the IRS's definition of jeopardizing investments explicitly excludes program-related investments, there is no such exception for mission-related investments (MRIs), which are made to generate a profit and to further a foundation's mission. Because MRIs may offer lower returns than non-MRI investments, many have questioned whether this could cause them to be treated as jeopardizing investments. However, on September 16, 2015, the IRS issued Notice 2015-62, which made clear that foundation managers may consider the relationship between an investment and the foundation's mission in making prudent, profit-driven investments. The Notice also implies that MRIs will not be considered imprudent because they offer an expected return that is less than what could be earned on other investments.198.1

For an investment to qualify as a PRI under § 4944(c), three requirements must be met:

p. 537. Insert the following after the first full paragraph on this page:

In Notice 2015-62,200.1 the IRS addresses questions that have arisen about whether an investment made by a private foundation that furthers its charitable purposes, but is not a PRI because a significant purpose of the investment is the production of income or the appreciation of property, is subject to tax under § 4944.

Although the regulations list some factors that managers generally consider when making investment decisions, the regulations do not provide an exhaustive list of facts and circumstances that may properly be considered. When exercising ordinary business care and prudence in deciding whether to make an investment, foundation managers may consider all relevant facts and circumstances, including the relationship between a particular investment and the foundation's charitable purposes. Foundation managers are not required to select only investments that offer the highest rates of return, the lowest risks, or the greatest liquidity so long as the foundation managers exercise the requisite ordinary business care and prudence under the facts and circumstances prevailing at the time of the investment in making investment decisions that support, and do not jeopardize, the furtherance of the private foundation's charitable purposes.

(b) Proposed Regulations: Additional Examples of PRIs

p. 540. Insert the following after the first full paragraph on this page:

In April 2016 the Treasury responded to comments to the philanthropy community and recognized that the existing regulations do not represent the diversity of investment opportunities available to foundations. New examples now make clear that PRIs are an applicable tool in advancing all charitable purposes. Original regulations that were published decades ago served as a tool to support economic development; however, in the present economy foundations are using them to support programs in science, technology, education, arts, and the environment. The examples further clarify that the PRIs can be used to support for-profit enterprises, individuals, and international recipients. The final regulations track closely to proposed regulations.

The preamble to the publication of the additional examples sets forth the principles that the IRS intends to post on its website:

- An activity conducted in a foreign country furthers an exempt purpose if the same activity would further an exempt purpose if conducted in the United States;

- The exempt purposes served by a PRI are not limited to situations involving economically disadvantaged individuals and deteriorated urban areas;

- The recipients of PRIs need not be within a charitable class if they are the instruments for furthering an exempt purpose;

- A potentially high rate of return does not automatically prevent an investment from qualifying as a PRI;

- PRIs can be achieved through a variety of investments, including loans to individuals, tax-exempt organizations, and for-profit organizations, and equity investments in for-profit organizations;

- A credit enhancement arrangement may qualify as a PRI; and

- A private foundation's acceptance of an equity position in conjunction with making a loan does not necessarily prevent the investment from qualifying as a PRI.

p. 543. Change the current subparagraph (c) to (d) and insert new subparagraph (c) as follows:

(c) Final Regulations: Additional Examples 11–19

Example 11 involved a private foundation's investment in a subsidiary of a drug company for the development of a vaccine to prevent a disease that predominantly affects poor individuals in developing countries. Under the investment agreement, the subsidiary is required to distribute the vaccine to the poor individuals in developing countries at a price that is affordable to the affected population and to promptly publish its research results; the example has been modified to make it clear that the subsidiary can also sell the vaccine to those who can afford it at fair market value prices. This clarification is appropriate given that the example also specifies that Y's primary purpose in making the investment is to fund scientific research in the public interest and no significant purpose of the investment involves the production of income or the appreciation of property.

Example 13 involved a private foundation that accepts common stock in a business enterprise as part of a loan to the business and that plans to liquidate the stock as soon as the business becomes profitable or it is established that the business will never become profitable. The sentence in the example regarding the liquidation of the stock has been removed to clarify that the foundation does not need to sell its stock in a business that becomes profitable for the investment in that stock to be a PRI. It is noted, however, that the establishment, at the outset of an investment, of an exit condition that is tied to the foundation's exempt purpose in making the investment can be an important indication that a foundation's primary purpose in undertaking the investment is the accomplishment of the exempt purpose.

Example 15 involved loans by a private foundation to two poor individuals living in a developing country where a natural disaster has occurred. The final regulations amend Example 15 to eliminate the reference to a natural disaster.

§ 6.6 NONPROFITS AND BONDS

(b) The Social Impact Bond: Impact Investing

p. 546. Add the following to the end of this subsection:

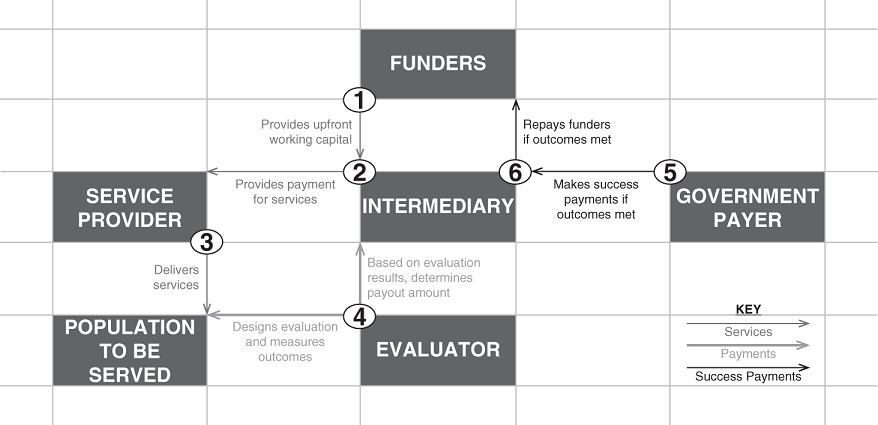

The following two diagrams illustrate the participating parties and flow of funds in these transactions.208.1 The CohnReznick presentation describes social impact bonds as a “pay for success” financing structure; “pay for success” being a category of contracts that looks to “result/outcomes” versus “activity/imputs.”208.2 The first diagram, “Overview of the PFS Process,” identifies the participants and their roles. The second, “PFS Financing: How It Works,” explains how the funds flow from the initial funding, usually by a for-profit, to a service provider through an intermediary, with payment by the government to the initial funder(s) if the evaluator determines that the delineated goals for the “population to be served” (which might in other contexts be identified as the “charitable class”) have been met.

The success of social impact bonds has been mixed and controversial.208.3 The first U.S. social impact bond involving New York City and Goldman Sachs did not achieve the goal of generating a reduced recidivism rate, relieving the government of its obligation to repay the investors. The second program, a “pay for success” program in Utah, provided support to struggling students in prekindergarten years with the expectation that early intervention would reduce the number of students needing special education assistance later on. That program was deemed a success, resulting in repayments to both the for-profit and the nonprofit investors, only to be followed by criticism of the metrics used in determining the program's achievements.208.4 “The concerns about the program are a reminder of how hard it is to properly structure public-private partnerships like social impact bonds, which depend on easily verifiable and commonly agreed-upon methods of measuring success for goals that can be hard to define. Finding such measurements is increasingly important as government programs face cutbacks and public officials look to find private investors willing to address the funding gap.” It remains to be seen whether the inherent challenges in this innovative approach to lessening the burdens of government will ultimately be viable.208.5

In an article entitled “Balancing Public and Private Interests in Pay for Success Programs: Should We Care About the Private Benefit Doctrine?” written by Sean Delany and Jeremy Steckel,208.6 the authors analyze how the private benefit doctrine might affect the structure of PFS programs in the United States and might limit or encourage their expansion in the future. At the time the article was written in Spring 2018 there were at least 13 domestic PFS projects underway in nine states as well as Riker's Island, addressing issues such as incarceration, recidivism, early childhood special education, foster care, homelessness, unemployment, and substance abuse, all of which are outlined in a chart describing the projects' objectives, individuals served, issue area, and initial private investment. The authors argue that the boundaries that tax-exempt organizations must observe when engaging with for-profit entities in the joint venture context to achieve their charitable missions are far from clear, because the private benefit doctrine has evolved in piecemeal fashion without a coherent conceptual framework. As PFS programs continue to develop, the exempt organizations need to ensure that they are not violating the private benefit doctrine. (See Chapter 5.)

§ 6.7 EXPLORING ALTERNATIVE STRUCTURES

(b) A New Legal Entity—the L3C—a Low-Profit LLC

p. 548. Add the following to the end of this subsection:

(c) Benefit and Flexible Purpose Corporation—A Legislative Approach

p. 551. Insert the following at the end of this subsection:

As of 2018, 37 states and the District of Columbia had passed some form of flexible purpose business legislation, and “approximately 7,000 businesses were organized as either L3Cs or benefit corporations.”233.1 These numbers should be analyzed in the context of the 30 million businesses in the United States.233.2 Thus, benefit corporations in their pure form have had good, but minimal, impact. Nevertheless, the limited number of benefit corporations and mere speculation about joint venture possibilities with these triple-bottom-line entities should not minimize the social impact that they promise.

Some scholars have argued that “[i]nstead of providing new sources of finance and protecting board members from liability, they have played a large part in an important conversation on the role of business in our country—namely, shifting the focus from shareholder maximization toward a more holistic and community-minded view of the role of business in society.”233.3

§ 6.8 OTHER APPROACHES (REVISED)

(c) Forgoing Tax Exemption

p. 553. Add the following at the end of this subsection:

The LLC has been used as a vehicle to fulfill charitable objectives for entrepreneurs seeking more flexibility in their philanthropic activity, including investing in and with for-profit partners.248.1 A for-profit LLC is not granted tax exemption and donations to it are not deductible, but there are potential tax benefits, particularly for successful entrepreneurs who own appreciated stock.248.2 This occurs because, as explained in Section 6.2, unless a special election is made, an LLC is a default pass-through entity whereby all financial activity passes through the LLC to the owners.248.3 If an entrepreneur donates appreciated stock to an LLC formed for charitable purposes, upon the sale of the stock by the LLC, any resulting capital gains taxes would flow through to the donor.248.4 On the other hand, if the LLC donated the appreciated shares to a § 501(c)(3) tax-exempt charitable organization, the donor would not only receive a deduction at fair market value of the stock, limited to 30 percent of adjusted gross income, but would also avoid the capital gains tax.248.5

A philanthropist-owner of an LLC can mitigate the financial consequences of sacrificing an immediate tax deduction for contributions made to a philanthropic LLC by having the LLC make an immediate charitable contribution to a qualifying charity.248.6 However, for wealthy philanthropists, such as Mark Zuckerberg, the disadvantage of forgoing an immediate charitable deduction is unlikely to dissuade them from organizing as a philanthropic LLC rather than a private foundation.248.7

A prominent example of forgoing tax exemption is the “Chan Zuckerberg Initiative,” whereby Mark Zuckerberg, founder of Facebook, and his wife, Priscilla Chan, are donating 99 percent of their Facebook shares (valued at approximately $45 billion at the time of the announcement) to advance their numerous charitable objectives, which initially included personalized learning, curing disease, and building strong communities.248.8 While media outlets referred to their investment vehicle as a charitable foundation, the couple created an LLC for the flexibility of being able to make political contributions,248.9 which private foundations are prohibited from doing, and for-profit investments, which are permissible investments for private foundations under defined circumstances.248.10 Mr. Zuckerberg explained that they sought “to pursue our mission by funding nonprofit organizations, making private investments and participating in policy debates.…”248.11

In regard to assertions that the structure would allow avoidance of taxes on the stock, Mr. Zuckerberg explained that he and his wife did not receive the charitable tax deduction allowed upon transfer of the stock to a charity and that they would pay capital gains tax when the LLC sells the stock.

Another example is the “Emerson Collective,” founded by Laurene Powell Jobs, widow of Apple CEO Steve Jobs. The Emerson Collective is also structured as a for-profit LLC. Jobs explains that the LLC structure furthers her personal interest in “deploying capital in the most effective way to create the greatest good that we can.”248.12 Demonstrating the flexibility of operation through an LLC are Emerson Collective's purchase of the majority shares in a magazine, The Atlantic, and airing a political advertisement on television explaining its position in regard to U.S. immigration policy.248.13

Other examples include the Downtown Project, a $350 million privately funded, for-profit LLC dedicated to revitalizing downtown Las Vegas, established by Zappos CEO Tony Hsieh;248.14 and the Omidyar Network, a $1.29 billion charitable for-profit LLC operating with an affiliate § 501(c)(3) foundation, established by eBay CEO Pierre Omidyar and his wife Pamela Kerr Omidyar.248.15 Others have elected to leverage their philanthropic power by combining assets (Warren Buffett248.16) and forgo “branding” their charitable activities.248.17

Social Entrepreneurship and Venture Philanthropy. Other trends in philanthropy include:

- Donors who view themselves as entrepreneurs, combining charitable goals with approaches typically found in the for-profit sector; examples:

- Tony Hsieh (Zappos)—$350 million in LLC to transform downtown Las Vegas.

- Pierre Omidyar (eBay)—uses § 501(c)(3) and LLC to operate Omidyar Network (approximately $1 billion); invests in entrepreneurs and various social missions.

- Gates Foundation—uses private foundations but heavy focus on mission-driven investments.

- Donors elect to leverage their philanthropic power by combining assets (Warren Buffett and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation) and forgo “branding” their charitable activities.

(d) Hybrid Structures

p. 554. Add the following at the end of footnote 253:

After significant lobbying, § 4943 was revised in 2018 to add new § 4943(g), which, as explained in Section 10.2, provides an exemption from the provisions requiring sale of stock in a situation whose circumstances mirror those of Newman's Own Foundation.

p. 555. Add the following to the end of this subsection:

In a recent Supreme Court case, Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc., the Supreme Court cited this page in the book, which described Google.org's advancing its charitable goals while operating as a for-profit corporation. See footnote 24 of the Hobby Lobby decision, 134 S.Ct. 2751 (2014) at p. 24. It recognized that while operating as a for-profit corporation, it is able to invest in for-profit endeavors, lobbying, and tap Google's innovative technology and workforce. The Supreme Court stated that:

In fact, recognizing the inherent compatibility between establishing a for-profit corporation and pursuing nonprofit goals, States have increasingly adopted laws formally recognizing hybrid corporate forms. Over half of the States, for instance, now recognize the “benefit corporation,” a dual-purpose entity that seeks to achieve both a benefit for the public and a profit for its owners. [Internal footnote omitted.]

(f) Cause-Related Marketing

p. 559. Add the following new subsection (g) at the end of this subsection and renumber the current (g) and (h) to (h) and (i), respectively.

(g) Commercial Co-Venture

A commercial co-venturer involves a for-profit person or company who regularly conducts a charitable sales promotion or underwrites, arranges, or sponsors a sale, performance, or event of any kind that is advertised to benefit a charitable organization.

A nonprofit may make an arrangement with a business to receive a percentage of sales; however, in at least 22 states, it is a regulated activity that may require a special registration filing. This activity is sometimes referred to as a “charitable sales promotion” or a “commercial co-venture.” State regulators have an interest in protecting charitable nonprofits from being taken advantage of and protecting consumer's expectations that the money will benefit charitable causes.

The law surrounding charitable sales promotions/cause-related marketing and commercial co-ventures is evolving. The state charitable solicitation registration laws often require nonprofits to file a copy of the contract governing the arrangement before any sales take place. Failure to register can lead to fines and in some states even criminal penalties. If the event is a one-time-only sales event, state law is less likely to require registration than if the sales promotion is ongoing. Furthermore, some states require nonprofits to file written reports on units sold and income received; consequently, the nonprofit may need detailed sales reports from the for-profit/other partner.

It is important to note that commercial co-ventures may also exist if one nonprofit agrees to sell products jointly with another nonprofit and agrees that a percentage of the sales will benefit one or the other of the nonprofits. The transaction may be structured as a license agreement involving royalties.

(h) Impact Investing (as renumbered above)

p. 559. Insert at the end of the subsection:

Impact investing may be defined as investments made in companies, organizations, and funds with the intention of generating measurable “social and economic impact” alongside a financial return. Investments typically target some level of financial return from below-market to risk-adjusted market rate and can be made, of course, in asset classes. It should be noted that impact-oriented investors can have different priorities which may fall either into a (1) “return first,” where the investors prioritize a financial return with an additional focus on impact; or (2) as a market or industry investment strategy, such as renewable industry.

The second priority would be investors that prioritize both financial and impact returns, often accepting a lower rate of return, if and when, impact goals are achieved. In this category companies would be selected that show leadership and innovation in social and/or environmental areas; finally, the third category would be investors that are typically foundations or public charities that prioritize impact returns over any financial return.

1. Impact Investing and the Commercialism Doctrine. In October 2020, the IRS released PLR 202041009, which denied federal tax exemption under §501(c)(3) to a nonprofit organization that structured and managed “double-bottom-line” impact investment funds.

This ruling is a “warning” to charities engaged in developing impact investing opportunities and may discourage foundations who seek to make program related investments (see Section 6.5) that intend to invest in certain impact funds. According to the facts, a nonprofit corporation was formed separately from its tax-exempt “parent” organization. The two entities were operationally integrated; the newly formed nonprofit (“manager”) applied for tax exemption and provided that it was formed exclusively for charitable purposes, intending to deploy capital into projects that perform a social good and need financing in the capital markets. Its focus was on those organizations that develop and operate affordable housing for the economically and physically disadvantaged and community facilities, such as schools and community health centers; businesses providing access to healthy foods; sustainable energy products, among others. In essence, the manager was focusing on enhancing economic opportunities in the low-income and underserved communities.278.1

The organization proposed to charge a substantially-below-market management fee intended primarily to cover its costs. The manager did not take a percentage of profits, that is, a “carried interest” from the funds.

The IRS did not view the fund's investment activity to be sufficiently charitable to overcome the “commercial” aspects of the organization's fund management activities. It concluded that the organization failed the operational test because a substantial portion of its activities consist of managing funds for a fee in order to provide market or near market returns for investors. It cited Rev. Rul. 69-528 that providing investment services for a fee to an unrelated organization is an unrelated trade or business. The IRS focused almost entirely on the organization's expectation of market (or near-market) returns for the investors and did not consider whether the charitable purpose prevailed over the potential rate of return. In effect, the IRS holding turned on the “commerciality” doctrine, concluding that a number of factors demonstrated that the manager was primarily engaged in a noncharitable commercial trade or business, that is, receiving a fee for a substantial purpose of providing market or near-market returns to investors. This was so notwithstanding the fact that the manager's activities were not commercial because its fees were lower than market and it cannot share in profits in contrast to commercial managers who receive a percentage of profits. The IRS was also concerned that the manager did not receive donations, grants, or contributions from the public. Finally, the IRS described the organization as “operationally integrated” with the parent, an existing 501(c)(3) organization. The IRS apparently concluded that using a nonprofit to offset costs and increased returns for investors was not an exempt purpose.

It is understood in the marketplace that the anticipated value of an PRI (a risk-adjusted return) needs to be distinguishable from that of a “return-seeking” investment.

In addition, clarifying that presence of possible market rates of return do not disqualify an investment or grant as an MRI/PRI. While Treasury recently attempted to make this clear, private foundations remain reluctant to find market rate investments as permissible in MRI/PRI decisions even when the primary reason for the decision is not the rate of return.278.2 See PRL 202041009.

NOTES

- 112.1 See subsection 4.5(a).

- 112.2 PLR 201503018 (Oct. 24, 2014).

- 112.3 See subsection 6.3(d)(ii).

- 112.4 Section 3.01(76), Rev. Proc. 2017-3, 2017-1 IRB 130 (12/29/16).

- 112.5 These facts are under a section titled “Representations Regarding Attribution.”

- 112.6 Although there is no discussion of Partnership's programs and activities, it is presumed that those activities would not be charitable/exempt in nature.

- 112.7 2017-1 IRB 1 (12/29/2016).

- 112.8 Transcript of February 24, 2017, remarks of Janine Cook, TE/GE Deputy Associate Chief Counsel, as delivered at the Washington Nonprofit Legal and Tax Conference as reported in EO Tax Journal 2017-68, April 7, 2017.

- 112.9 PLR 202005020 (January 31, 2020).

- 112.10 This subsection is based upon materials prepared by Ronald Schultz for presentation at Georgetown Law Center, Special Topics in Exempt Organizations (2020).

- 112.11 In addition, under the subsidiary's bylaws, the parent has certain reserved powers to:

Approve or reject executive and administrative leadership.

Establish general guiding policies.

Approve or disapprove annual operating and capital budgets.

Direct the placement of funds and capital.

Approve or disapprove salary rates for administrative and department head personnel.

- 112.12 The IRS did not rule on inurement, although it was requested by the parent.

- 151.1 See Section 8.7.

- 151.2 TAM 9651001 finds that sale of partnership with acquisition indebtedness generates UDFI.

- 198.1 IRS Notice 2015-62 (Sept. 16, 2015). Specifically, the IRS Notice provides that an investment made by a private foundation will not be considered to be a jeopardizing investment “if, in making the investment, the foundation managers exercise ordinary business care and prudence (under the circumstances prevailing at the time the investment is made) in providing for the long-term and short-term financial needs of the foundation to carry out its charitable purposes.”

- 200.1 2015-39 IRB 411 (Sept. 15, 2015).

- 208.1 “Social Impact Bonds and Pay for Success—What Is It?,” prepared and presented by CohnReznick at the CohnReznick 5th Annual New Markets Tax Credit Summit, May 2016.

- 208.2 Id.

- 208.3 Kenneth A. Dodge, “Why Social Impact Bonds Still Have Promise,” New York Times, Nov. 13, 2015.

- 208.4 Nathaniel Popper, “Success Metrics Questioned in School Program Funded by Goldman,” New York Times, Nov. 3, 2015.

- 208.5 Id.

- 208.6 See New York University Journal of Law and Business 14, no. 2 (Spring 2018).

- 233.1 The material added in this subsection is based upon research prepared by Michelle Gough, JD, PhD from her graduate tax paper at Georgetown University Law Center, Special Topics in Exempt Organizations, entitled “Benefit Corporations: Are the New State Created Entities Creating Both New C-Corps and New Possibilities in Joint Ventures?” Elizabeth Schmidt, New Legal Structures for Social Enterprises: Designed for One Role but Planning Another, 43 Vt. L. Rev. 675 (2019). In addition to L3Cs and benefit corporations, four states have a social purpose corporation (Washington, California, Florida, and Texas) and three recognize the benefit limited liability company. Id. For other sites that track social enterprise legislation, see State by State Status of Legislation, Benefit Corporation, http://benefitcorp.net/policymakers/state-by-state-status.

- 233.2 Id. Citing “Quick Facts United States,” U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045217 (calculating that in 2016, the United States had 7,757,807 businesses with employees and 24,813,048 without employees).

- 233.3 See Schmidt, Footnote 54.

- 248.1 Garry W. Jenkins, Who's Afraid of Philanthrocapitalism?, 61 Case W. Res. L. Rev. 753, 756 (2011); most LLC statutes permit LLCs to engage in any lawful activity. See Mohsen Manesh, Legal Asymmetry and the End of Corporate Law, 34 Del. J. Corp. L. 465 (2009).

- 248.2 This analysis is based on research prepared by Caroline Koo and is adapted from her graduate tax paper at Georgetown University Law Center, Advanced Topics in Exempt Organizations.

- 248.3 See Section 3.5.

- 248.4 See IRC §§ 1221–1223.

- 248.5 See Section 2.1.

- 248.6 This comment is based upon a paper submitted by Eunice Lim from her graduate tax paper at Georgetown University Law Center, Special Topics in Exempt Organizations.

- 248.7 See Dana Brakman Reiser, Disruptive Philanthropy: Chan-Zuckerberg, the Limited Liability Company, and the Millionaire Next Door, 70 Fla. L. Rev 921, 951 (2018) (“In theory, the percentage limits and lack of a full-market-value deduction for donations to private foundations could enable a transfer of appreciated assets to a philanthropy LLC followed by a speedy donation to a public charity to yield a greater tax benefit than the same transfer to a private foundation.”). Barbara Benware, Donating Appreciated Publicly Traded Securities to Charity, Schwab Charitable, https://www.schwabcharitable.org/public/charitable/nn/noncash_assets/appreciated-public-traded-securities.html.

- 248.8 “A Letter to our Daughter,” Dec. 1, 2015, available at facebook.com.

- 248.9 “Mark Zuckerberg Is Giving Away His Money, but with a Twist,” Dec. 2, 2015, available at fortune.com.

- 248.10 See subsection 6.5(b).

- 248.11 “Mark Zuckerberg Defends Structure of His Philanthropic Outfit,” Dec. 4, 2015, https://mobile.nytimes.com/2015/12/04/technology/zuckerberg-explains-the-details-of-his-philanthropy.html?smprod=nytcore-iphone&smid=nytcore-iphone-share.

- 248.12 Ruth McCambridge, “The Atlantic to be Sold to Jobs' Social Investment LLC,” Nonprofit Quarterly, July 31, 2017, https://nonprofitquarterly.org/2017/07/31/majority-shares-atlantic-sold-jobs-emerson-collective.

- 248.13 Id.; Theodore Schleifer, “Laurene Powell Jobs Is Airing Political Ads in the Wake of Trump's DACA Decision,” CNBC, Sept. 5, 2017, https://www.cnbc.com/2017/09/05/laurene-powell-jobs-airing-ads-after-trump-daca-decision.html.

- 248.14 About Us, DOWNTOWNPROJECT, Mar. 9, 2018, downtownproject.com.

- 248.15 Financials, Omidyar Network, https://www.omidyar.com/financials (last visited May 15, 2018) [hereinafter Omidyar Network].

- 248.16 “In 2006, Buffett pledged most of his fortune to the Gates Foundation and to four charitable trusts created by his family.… His gift to the Gates Foundation of 10 million shares of Berkshire Hathaway stock, to be paid in annual installments, was worth approximately $31 billion in June 2006.” Leadership, Warren Buffett, Trustee, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, https://www.gatesfoundation.org/Who-We-Are/General-Information/Leadership/Executive-Leadership-Team/Warren-Buffett.

- 248.17 See Chapter 8 discussion on Royalties and Branding.

- 274.1 In addition, the corporate sponsorship rules under § 501(i) need be reviewed. See Section 8.4.

- 278.1 The manager registered as a state-registered investment advisor and planned to register with the SEC once they satisfied the eligibility requirements.

- 278.2 See comments of Council on Michigan Foundation to IRS, dated May 28, 2021, with regard to matters to be included in the 2021–2022 Priority Guidance Plan.