4. Hunt for Patterns

“To understand is to perceive patterns.”

—Isaiah Berlin, political philosopher

In our research on Rapid Response Teams, we spoke with many nurses. We asked them to explain how they recognized the early warning signs of a patient headed for distress. In short, we wanted to know how they became effective problem-finders. Did it simply involve continuous monitoring of vital signs, with calls for assistance initiated when key metrics moved outside acceptable ranges? Time and time again, we heard that highly experienced nurses spotted trouble before the patient’s vital signs became abnormal. In one hospital, we heard that more than 20% of recent Rapid Response Team calls originated with a nurse who requested assistance because “something just did not feel right.” In contrast, novices often did not notice a problem until the quantitative measures moved outside the acceptable range. By then, a patient’s condition might be quite serious.

We probed to find how the experienced nurses often recognized trouble unfolding at its early stages. What caused them to become concerned? One nurse said to us, “You just have a sense...I can’t tell you exactly how that happens, but you somehow put two and two together. You look at the lab values and the patient, and you get a picture of what is going on. Sometimes it’s just a sixth sense. I can’t explain it!” Another nurse commented, “I’ve been a nurse for twenty-two years. You develop instincts about patient behavior and appearance. You can just look at an individual and say ‘Uh-oh!’ It might be their skin tone, or the way someone is talking. Ninety percent of the time, our gut is right. Sometimes, you can’t quite put a finger on it, but you know the patient is crashing.” We heard similar comments from nurses on countless occasions during our study.

Did this mean that novices could not become superb problem-finders until they had accumulated decades of experience? No, we discovered that the Rapid Response Team process could accelerate the inexperienced nurses’ ability to spot trouble brewing in its infancy. Nurses kept telling us that calling a Rapid Response Team for assistance not only helped the patient, but it also sharpened their instincts. They learned from watching how and why their more experienced peers decided to call an RRT even when they lacked concrete data to support their concerns. Moreover, they learned by observing and interacting with the experts on the Rapid Response Teams. The novices watched how the RRT members assessed patients. What tests did they conduct? What questions did they ask? How did they draw conclusions based on limited data? How did they make links back to past cases?

The RRT members viewed each call as a “teaching moment” in which they could assist the patient and mentor the inexperienced nurses. The RRT members often asked the inexperienced nurses a series of questions about the patient’s behavior and appearance over the previous few hours. They commented on signs of trouble that the novice might have missed. They “thought out loud” as they assessed the patient so that the novices could understand their thinking. Over time, the novices became more adept at noticing subtle signals of oncoming patient distress. As one RRT member said, “the program helps develop a new nurse’s sixth sense.” In short, intuition seemed to be a key problem-finding capability at these hospitals. However, good instincts were not purely an accident of birth. One could not conclude that some individuals simply were more fortunate, or more intelligent, and thus had better instincts than others. In fact, it appeared quite possible for experts to help others hone their intuition, thereby enabling them to become better problem-finders.

A sixth sense, gut instinct, intuition...We all have experienced this phenomenon, but what precisely does it mean? How does the intuitive process work? Can we actually harness and enhance our intuition so as to become better problem-finders?

In 1985 psychologist Gary Klein set out to study how firefighters made life-or-death decisions.1 In the process, he learned (unexpectedly) about the intuitive process. In his very first interview, Klein asked a fire commander to describe a very challenging incident in which he had been involved. The commander insisted that “ESP” had been a critical factor in making a good decision. Extrasensory perception? Was the commander kidding? The commander explained how he had once arrived at the scene of a seemingly small and straightforward kitchen fire. His men began spraying water at the fire from the living room, but “the fire just roared back at them.”2 After a few repeated attempts, the commander was puzzled. Why wasn’t the water effective in fighting the fire? Then, his “sixth sense” kicked in, and he became very concerned. He ordered his men out of the house, despite not knowing precisely why the alarm bells had gone off in his head. Soon thereafter, the living room floor collapsed. If the firefighters had remained in the house, they could have been seriously injured or killed.

As Klein asked probing questions, the commander described what he was thinking at the time of the fire. He recalled being surprised that the water had virtually no impact on the fire. He remembered being puzzled by how hot it was in the living room. A small kitchen fire should not have emitted that much heat. Meanwhile, he heard very little noise when he was standing in the living room. That seemed odd, given that a hot fire such as this one should have been rather noisy. As it turned out, the floor collapsed because the main fire was located in the basement, directly beneath where he had been standing. That explained the ineffectiveness of the water, the extreme heat, and the low noise level. The commander did not know that at the time, but he knew that the situation didn’t feel quite right. His intuition had helped him detect a serious problem. Klein explained his interpretation of the commander’s thought process:

“The whole pattern did not fit right. His expectations were violated, and he realized that he did not quite know what was going on. That was why he ordered his men out of the building...The commander’s experience had provided him with a firm set of patterns. He was accustomed to sizing up a situation by having it match one of those patterns. He may not have been able to articulate the patterns or describe their features, but he was relying on the pattern-matching process to let him feel comfortable that he had the situation scoped out.”3

Over time, Klein studied the decision-making of a variety of experts in other fields, including pilots, military leaders, and nurses. He concluded that intuition plays a powerful role in how experts size up a situation and make decisions. According to Klein, intuition is fundamentally a pattern-recognition process. When individuals encounter a situation, they try to determine whether it fits (or does not fit) the patterns of their past experience. That pattern-recognition process often involves drawing analogies between the current situation and past situations. The pattern-recognition activity then triggers a set of “action scripts” that enable individuals to decide and act without going through an elaborate comparison of multiple alternatives. Instead, they consider a potential plan of action, and they mentally simulate whether that plan might be effective. If so, they act. If not, they consider a different scenario/option.4

Klein argues that intuition gradually develops as someone develops deep expertise in a specific field. As an individual encounters more and more situations, he or she develops a more sophisticated ability to identify and match patterns. In other words, although we are not always aware of it, the mind hunts for patterns in all the situations that we encounter, and it uses pattern-matching to spot problems. Going back to the commander in our example, we see that he could not match the kitchen fire with the patterns from his past experience. He had seen many kitchen fires, and based on that experience, he expected to see certain patterns in terms of the noise level, the heat, and how water affected the fire. However, in this case, the cues that he observed did not match those patterns. Thus, his intuition told him that he was not experiencing a simple contained kitchen fire. He could not rely on the actions that he would have automatically and instinctively embarked upon if the situation matched the pattern of past kitchen fires. The lack of a pattern match led him to conclude that he might be facing a much more serious problem than he first envisioned.5

As you learned from the firefighting example, the intuitive process rests firmly on our ability to draw appropriate analogies. Our minds appear to constantly ask the question: To what past circumstance is this current situation analogous? As it turns out, we use analogies to make decisions all the time. Sometimes, we do so unconsciously, and in other cases, we draw an analogy to a past situation in a much more open and deliberate fashion. Unfortunately, we sometimes draw inappropriate analogies, or we arrive at erroneous conclusions based on the analogies we make. Our search for patterns leads us astray. As a result, we do a poor job of detecting problems. We overestimate some and miss others.

Richard Neustadt and Ernest May have conducted groundbreaking research on the misuse of analogies.6 They studied the American presidency and discovered a number of examples of faulty reasoning by analogy. Take, for example, the 1976 “swine flu” incident. In that situation, President Gerald Ford and his advisors drew an erroneous analogy to the infamous flu epidemic of 1918. The faulty analogy led them to dramatically overestimate the seriousness of the problem they faced. As a result, they embarked on a very expensive and unnecessary immunization program. Roughly five hundred people experienced a serious side effect that was linked to the immunizations, and twenty-five people died. The settlements cost the federal government millions of dollars. More people died from the immunizations than from the flu itself. The credibility of public-health authorities, as well as the Ford administration, took a major hit.

The incident began with a report that a soldier at Fort Dix had died from the flu, and several other soldiers became ill. The virus appeared to be chemically related to one that commonly affected pigs but that had not afflicted humans since the 1930s. However, experts believed that the 1930s virus represented a weaker version of a virus that caused a massive epidemic in 1918. In that year, a powerful and virulent influenza killed 500,000 Americans and roughly twenty million people around the globe. Many young adults in their prime died suddenly from this flu, apparently within a day or two of being diagnosed.

When the soldier died at Fort Dix, people drew an analogy to the 1918 epidemic. In part, they did so because of the biological link to the virus that caused so many deaths back then. Experts did not believe that the current virus that had killed the soldier at Fort Dix was as dangerous, but they could not be sure. Given the uncertainty, people made judgments based on their vivid memories of the stories they had heard from their parents about the horrendous epidemic of 1918. As Neustadt and May write, “it seems that almost everyone at higher levels of the federal government in 1976 had a parent, uncle, aunt, cousin, or at least a family friend who had told lurid tales of personal experience with the 1918 flu.”7

Added pressure arose because Centers for Disease Control (CDC) officials did not want to repeat the experiences of 1957 and 1968. In those years, flu epidemics (unrelated to the 1918 virus) had caught the federal government off guard. Experts had come to believe that major shifts in influenza viruses took place roughly every decade; they worried that the death of this soldier might indicate the onset of another dangerous shift. Officials at the CDC wanted to demonstrate that they could move proactively to head off another epidemic; they wanted to show the country that they could do better than they had in 1968.

Over the course of ten weeks, forty million people received immunizations. However, a number of delays and public-relations blunders took place. Moreover, not a single person died anywhere in the world from swine flu, unless they had been in close contact with pigs. Meanwhile, roughly five hundred people contracted Guillain-Barré syndrome, apparently due to the vaccine. The disease can cause paralysis, and in the case of twenty-five individuals, it led to death due to respiratory problems. Because no one had contracted swine flu since the soldiers at Fort Dix had become ill, the government suspended the vaccination program. The initiative cost the government $137 million, plus millions more to settle cases brought by the families of those afflicted with Guillain-Barré syndrome. Newspapers at the time described the immunization program as a “fiasco” and a “debacle.”8

Neustadt and May concluded that the Ford administration and the CDC had fallen victim to a captivating analogy rooted in folk memories of a horrible tragedy nearly sixty years earlier. The scholars explain:

“Literally, the analogy was not ‘irresistible.’ Its relevance was limited, its application arguable, and its guidance dubious on what to do. It served better as a warning light than as a beacon. Yet it precipitated action on the basis, solely, of ‘worst-case’ analysis without preparing to accommodate the likely case. Captivated, the decision-makers failed to hedge by light of the uncertainty.”9

What lies at the heart of faulty reasoning by analogy? Neustadt and May argue that we tend to dwell on and overestimate the similarities between two situations that we deem analogous, and we ignore many of the fundamental differences. The Ford administration certainly did both.

When we reason by analogy, we make a number of assumptions. For instance, officials assumed that no serious side effects existed, and that one dose of the vaccine would suffice. Both assumptions proved incorrect. In fact, government officials committed three types of errors with regard to the assumptions they made. They failed to surface all their implicit assumptions, they confused facts with assumptions, and they failed to test and probe their assumptions carefully. We all exhibit these errors at times. Neustadt and May argue that government officials made at least seven key implicit assumptions during the swine flu incident, and every one of those assumptions “would turn out wrong in practice.”10 In sum, the Ford administration “found” a problem that did not truly exist, because they engaged in faulty reasoning by analogy. They hunted for a pattern, but they made the wrong match.11

Companies, too, draw poor analogies to their past experiences. Scholars Giovanni Gavetti and Jan Rivkin argue that business executives get in particular trouble when they start with “a solution seeking a problem.”12 In typical analogical reasoning, we search our past experience for analogies to a current situation we are trying to address. However, in some cases, executives begin with a solution they adore, perhaps a business model that has been successful for them. Then, they search for new problems to which they can apply that solution. They have a hammer in search of a nail. This type of problem-finding can be highly problematic.

Take Zoots, the dry cleaning business founded in 1998 by Staples CEO Tom Stemberg and Todd Krasnow, Staples’ head of sales and marketing. It began with a great deal of promise, but it burned through a lot of cash and struggled to turn a profit. The company ultimately dissolved in early 2008, with the sale of stores and delivery routes to rivals. Two former managers acquired some of the firm’s locations and the rights to the brand name.13

What happened? The strategy began with the founders drawing a number of analogies between the office supply business and the dry cleaning industry. Stemberg and Krasnow saw an opportunity to consolidate a highly fragmented industry, as they had done with tremendous success in office supplies. Witnessing the thousands of mom-and-pop operations around the country, they believed they could exploit economies of scale relative to these tiny independents. In office supplies, they had built their own distribution centers to serve stores in a hub-and-spoke logistics network. This turned out to be much more efficient than direct store delivery by multitudes of vendors, or distribution through independent wholesalers. It gave Staples a huge advantage over independent office supply stores. In dry cleaning, Stemberg and Krasnow envisioned a hub-and-spoke network with centralized cleaning facilities serving an array of stores in a geographic area. They believed they could achieve a cost advantage over the independent cleaners, while providing an array of more innovative services.14

As it turned out, the dry cleaning industry exhibited a number of profound differences compared to office supplies. As Zoots tried to grow, it encountered numerous operational problems. Efforts to operate centralized cleaning facilities led to quality problems, burdensome fixed costs, and difficulties dealing with wild swings in volume from day to day. At the heart of it, standardization and scale provided Staples with a competitive advantage in office supplies. Dry cleaning remained a business that was fundamentally about customization at the local level; thus, it was far less amenable to the exploitation of scale economies.15 Bill Fisher, chief executive of the Drycleaning & Laundry Institute, explained the challenge for large chains in this industry: “Unlike fast-food chains that standardize all the food and cooking techniques, dry cleaners deal with thousands of different garments with unique issues on a daily basis.”16

Other companies also have struggled with strategies born from the misuse of analogies. In the beer industry, Pete Slosberg achieved great success with the founding of his microbrewery brand—Pete’s Wicked Ale. After selling his company, he searched for another industry to which he could apply the business model that had worked so well in craft brewing. Slosberg founded Cocoa Pete’s Chocolate Adventures—a manufacturer of gourmet chocolates—in the spring of 2002. A Stanford case study explains how Slosberg ended up drawing an analogy between beer and chocolate:

“To Slosberg and his advisors, the domestic chocolate industry seemed to represent a near-identical match to the beer industry of the 1980s in market dynamics and composition. When they compared the different brands of chocolate by price per pound, their research indicated that the domestic market was dominated by three companies (Hershey, Mars, and Nestle) producing less flavorful, mass-market products, just like the beer industry’s three domestic players (Anheuser Busch, Coors, and Miller) produced mass-market, less flavorful beer. Their analysis pointed to a gap in the domestic market of higher quality gourmet chocolate where they could move in, just as Pete’s Brewing Company targeted the gap in domestic super premium beer. Additionally, many chocolate makers, such as Guittard, had excess production capacity at their plants and would happily produce private label chocolates, much like the many breweries with excess capacity Pete’s Brewing Company could have used to produce Pete’s Wicked Ale in the mid-1980s.”17

Of course, key differences existed between beer and chocolate. For instance, the target market for craft brews such as Pete’s Wicked Ale consisted of males aged eighteen to thirty-four; the target market for premium chocolate tended to be wealthier, more educated females. Moreover, outsourcing production to chocolate makers with excess capacity proved to be very challenging. Chocolate manufacturing and product packaging, in general, turned out to be much more complex than craft brewing.18 Now six years since its founding, Cocoa Pete’s has not approached the success achieved by Pete’s Brewing.

Finally, we have the infamous case of Enron. In the early 1990s, Jeffrey Skilling built a lucrative business trading natural gas. People became very excited about the potential of this concept. Gradually, Enron began to look for other markets to which it could apply the same business model. Ultimately, the firm tried to build trading businesses in industries as diverse as electric power, pulp and paper, trucking, and broadband.19

How did Enron choose to enter these disparate markets? It drew analogies between these industries and the natural gas market of the late 1980s. In fact, the company identified a list of key characteristics of the natural gas market. Executives described these attributes as “the template.” They believed that they could apply their natural gas trading model to any industry that exhibited these characteristics; in other words, they could just transfer the template. Here are some examples of the attributes they considered: Was the product a fungible commodity that could be divided into indistinguishable units? Did it have a complex and unique logistics system? Were there many buyers and sellers who lacked market power? Could one create standard contracts and product offerings? Could the product be purchased and sold for varying periods of time? Could Enron create financial instruments to hedge risk associated with these commodities? Managers used this template to search for new business opportunities. At its heyday, Enron had hundreds of bright young people searching madly for the next business to which they could apply the natural gas model. Each talented young person sought the opportunity to pitch his or her idea to senior executives.20

What went wrong with this approach to new business creation? It encouraged managers at Enron to focus on the similarities between the natural gas market and these other industries as they drew analogies. However, it did not cause them to attend to the fundamental differences between markets. Many industries exhibited a majority of the attributes listed on Enron’s “template.” However, most industries also exhibited key differences that made establishing a profitable trading model quite difficult, particularly for an energy company without experience in that particular market. Going through the template did not require managers to think about those differences. It simply asked them to consider whether the similarities were present.

These examples—Zoots, Cocoa Pete’s, and Enron—all demonstrate how vulnerable business leaders can be to faulty reasoning by analogy. Executives appear to be especially vulnerable when they have had great past success, like Krasnow at Staples, Slosberg at Pete’s Brewing, and Skilling with the Enron gas trading business. We sometimes find ourselves starting with solutions in search of problems. As a result, we become even more likely to dwell on the similarities and discount the differences inherent in the analogy we have chosen. The lesson is simple: We can and should hunt for patterns all the time, but beware—we do not always make the right matches. Sometimes, we force matches where a pattern does not fit because we have a hammer in search of a nail.

Let’s turn now to how leaders can refine and enhance their pattern-recognition capabilities. We focus on how to reason more effectively by analogy, mentor inexperienced employees to help them spot problems sooner, and employ systematic analysis to spot patterns across your organization.

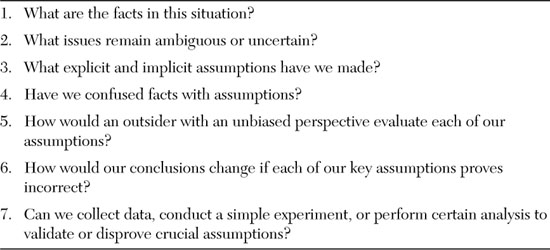

Neustadt and May have proposed a simple methodology for enhancing our pattern-matching capabilities. They argue that leaders should begin by closely examining the current situation they face and then distinguishing what is Known, Unclear, and Assumed. Leaders cannot identify a useful analogy, or use it properly, if they do not have a clear grasp of the situation at hand. The exercise forces people to surface implicit assumptions and to separate assumption from fact. Seven questions can help you scrutinize your assumptions effectively (see Table 4.1).

Neustadt and May also suggest that leaders scrutinize their analogies closely, by drawing up two lists, before they try to determine how to act in the current situation. These lists should identify all the Likenesses and Differences between the current situation and the analogous one. Making people focus explicitly on the differences helps protect against becoming captivated by analogies that appear to match beautifully at first glance.

Leaders should try to write down these lists, “even if only on the back of an envelope.”21 The exercise of writing things down adds discipline and rigor to a leader’s thought process. Moreover, it provides others an opportunity to offer more thoughtful criticism, after considerable reflection upon what they have read, rather than asking them to react quickly to statements bandied about in formal or informal meetings. Neustadt and May cite former Chrysler CEO Lee Iacocca’s advice in this regard: “In conversation, you can get away with all kinds of vagueness and nonsense, often without realizing it. But there’s something about putting your thoughts on paper that forces you to get down to specifics. That way, it’s harder to deceive yourself—or anybody else.”22

Neustadt and May explain how this methodology could have helped President Truman when he chose to go to war in Korea. At the time, Truman and his advisors relied on an analogy to the 1930s, when appeasement encouraged further aggression and ultimately led to World War II. The analogy has been used time and time again over the years, sometimes quite inappropriately. Truman explained his thinking about Korea in his memoirs:

“I recalled some earlier instances: Manchuria, Ethiopia, Austria. I remembered how each time that the democracies failed to act it had encouraged the aggressors to keep going ahead. Communism was acting in Korea just as Hitler, Mussolini, and the Japanese had acted ten, fifteen, and twenty years earlier.”23

Neustadt and May defend Truman’s decision to come to the aid of South Korea. However, they point out that a disciplined examination of the 1930s analogy might have prevented one crucial error during the war—namely, the decision to allow General Douglas McArthur to push into North Korea in hopes of reunifying the nation after his initial success at driving the Communist troops out of the south. That decision, of course, ultimately led to the introduction of Chinese troops into the war. McArthur’s troops were driven back, and the war’s popularity at home plummeted.

Neustadt and May explain how a more careful analysis of the 1930s analogy might have prevented Truman from trying to reunify Korea. They argue that a comparison of Likenesses and Differences would have highlighted that “the President’s chief concern was not Korea.”24 Instead, Truman wanted to deter further Soviet aggression and maintain the new postwar system of collective security. Careful examination of the analogies to the 1930s would have revealed that Truman wanted to use force to repel the aggressors, but not to “punish” or “seek retribution” against them for invading South Korea. After all, Truman and his advisors did not believe that the Allied forces should have “solved the Rhineland crisis by themselves occupying some portions of Germany” during the 1930s.25 However, because the Truman administration did not fully vet the analogy, they allowed their original objective to drift from repelling the aggressors to reunifying the Korean peninsula. They discounted the possibility of Chinese entry into the war, because that dynamic was fundamentally different from anything they remembered from the 1930s.26

We can hone our pattern-recognition capability through interacting with experts in various fields, by digging in to understand their thought processes. How do they size up situations? How do they recognize problems and trends? What subtle signals serve as warnings to them? We also can foster mentoring relationships, whereby our internal experts can hone the pattern-recognition capacity of the less experienced members of our organizations.

The hospitals in our study coached the experts to mentor the novice nurses. As one hospital leader told us, “We wanted to mentor the more inexperienced nurses, and we wanted to help them develop their instincts, their ability to see when a patient might be deteriorating, even if the vitals looked OK.” How did that mentoring take place? One hospital leader explained, “Often, the Rapid Response Team members will ask leading questions, sort of like the Socratic method. The idea is to take the floor nurse through a thought process... The mentoring, of course, comes later if the situation is a true crisis. Just act, and do the talking through the thought process later.”

The experts pointed out that they sometimes needed to show restraint in order to share their intuition with less experienced colleagues. One nurse commented that, “It’s straightforward for me to just act automatically. Sometimes, though, I do talk out loud about it as I’m doing something... Learning then is by osmosis.” Experts feel tempted to just take over in many situations, but then the less experienced colleague may not understand how an expert arrived at certain conclusions. Communication of an expert’s thought process becomes critical. One expert explained, “You just talk through your thought process at times, or the new nurse asks: ‘How did you know?’ Then, you can try to explain what you saw when you assessed the patient.” Sometimes, that “talking out loud” occurs in real time; in other situations, it happens during a debriefing session after a situation has been resolved.

To help this learning take place, the hospitals find that it helps for the experts to show empathy for their inexperienced peers. They need to show the novices that they once walked in their shoes. They did not always possess the intuition to spot problems quickly and proactively. It took time to develop those instincts. One hospital leader explained:

“We encourage the RRT to share a past experience, to show empathy with the floor nurse... ‘I was scared when I first encountered this type of situation too...let me tell you about it.’ We also want the RRT to share what they did in that past experience, what they thought it was, and how they might not have perceived a situation correctly when they first encountered it. In other words, show that they too were a novice once, and were surprised by something being different than they expected and unfamiliar to them.”

Mentoring, then, requires astute observation and active listening on the part of the inexperienced, as well as empathy and communication skills on the part of the expert.27 Most of all, learning simply occurs “by osmosis.” As you talk through situations with others, and watch them handle those circumstances, you should keep asking yourself: What are they seeing that I am not seeing? How have they fit this situation into a pattern of their past experience? What cues are they attending in the current situation? As a leader, you can hone your own pattern-recognition capabilities, as well as encourage the experts in your organization to serve as mentors. The organization will benefit if everyone becomes better at recognizing patterns and spotting problems before they blossom into catastrophes.

As small problems occur in your organization, consider how you catalog those incidents. Keeping careful track enables you to go back later and mine the data for patterns. Have we seen this type of problem repeatedly in various parts of the organization? What do these incidents have in common? Do we have a pattern here, suggesting a larger, more systemic problem?

At the hospitals, people track all the RRT calls. At one hospital, we observed a number of weekly review meetings that took place. A team of people sorted the data in many different ways. They asked questions such as: Does a particular unit seem to have a disproportionate number of incidents? Do we have a rash of calls associated with one particular “trigger” such as low oxygen saturation? Do the patients who require assistance have anything in common? At one weekly meeting, the team came to an important conclusion: Patients recovering from knee replacement surgery seemed to be experiencing a disproportionate number of RRT calls. Further analysis identified several factors contributing to this problem, and the team put in place several remedies to reduce the risk to these patients. In another hospital, similar review meetings revealed that the hospital had an over-sedation problem. Frequent RRT calls seemed to be occurring because patients experienced respiratory distress, as sometimes occurs with the use of sedatives. The hospital revised its policies for administering sedatives and monitoring those patients afterward so as to address the problem.

Other businesses can certainly mine data to hunt for patterns that reveal potentially serious problems within the organization. However, one can find patterns across multiple minor problems or incidents only if the data exist. In other words, transparency proves essential to pattern recognition. If the hospital did not know about the patients whose oxygen saturation had dropped unexpectedly, it would not have discovered its over-sedation problem. To see the patterns, people need to be willing to share their knowledge of situations that may not be transpiring as expected. They cannot fear the consequences of an organizational blame game.28

At PayPal, the highly profitable online payments unit of eBay, a unique process helps leaders spot patterns and identify problems before they mushroom. PayPal manager Mario Shiliashki described to me how each team within the company sends out a “PPP” (Progress, Problems, and Plans) report on a weekly basis.29 The report identifies the team’s progress on current initiatives, the problems it currently faces, and its plans to rectify those issues. The concise PPP report goes to a number of peer units, as well as to superiors within the organization. Shiliashki spends time each week reviewing the roughly ten to fifteen PPPs he receives. The transparency proves crucial to the company’s continuous-improvement efforts. By examining a range of PPPs, each manager can see patterns across multiple units at PayPal. Are similar problems occurring in multiple units? Can teams collaborate to solve problems that they all face? Shiliashki explained that the PPP process “helps us get ahead of problems.” In so doing, he finds that the process helps avoid the “blame game,” because fewer “bad news surprises” occur. People hear about issues early, and they work collaboratively to solve them.

Let’s close this chapter with a thorny question: What precisely do individuals learn at business school, whether in MBA classrooms or Executive Education programs? Students surely ask themselves this question when they hand over hefty amounts of money for tuition each year. Well, faculty members certainly teach a number of conceptual frameworks, and they expect the students to master them. Frequently, professors use case studies to help the students apply those frameworks to real managerial situations. Business education, though, involves far more than the learning of certain analytical techniques.

Beyond the frameworks, the case method of business education ultimately helps to hone an individual’s pattern-recognition ability. Over the course of an MBA program, students see hundreds of scenarios through case studies. Clearly, the cases do not serve as pure substitutes for the real experience that experts achieve in the field. However, as students immerse themselves in these case situations, and compare and contrast them over time, they begin to recognize patterns. They draw analogies to past case studies. Thoughtful students begin to develop the capacity to discern when a situation fits patterns that they have seen repeatedly, and when it does not match prior patterns. In short, business education and leadership development programs offer the opportunity for leaders to become more adept at hunting for and spotting patterns.30

The promise of such learning experiences often falls short, though. Why? In part, too many case studies deprive students of the opportunity to work on their problem-finding skills. As former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara (a Harvard Business School professor in the 1940s) once told me, case studies too often define the problem for the student.31 They need only apply the right analytical technique to solve the problem. The best case studies make the students assess a situation, search for patterns, and try to discern the problem for themselves. Those types of cases provide enduring value, because they help build leaders’ problem-finding capabilities—something they will desperately need in the “very messy” real world.

1 Gary Klein has described his work in two excellent books. Klein, G. (1999). Sources of Power: How People Make Decisions. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; Klein, G. (2004). The Power of Intuition: How to Use Your Gut Feelings to Make Better Decisions at Work. New York: Doubleday.

2 Klein, (1999). p. 32.

3 Ibid

4 Daniel Isenberg has also done some excellent research on intuition—in particular, on how managers combine intuition and rational analysis. See Isenberg, D. (1984). “How senior managers think.” Harvard Business Review. 62(6): 80–91.

5 I have written several case studies that focus, in part, on the intuitive decision-making process. See Roberto, M. and G. Carioggia. (2004). “Electronic Arts: The Blockbuster Strategy.” Harvard Business School Case Study No. 9-304-013; Roberto, M. and E. Ferlins (2004). “Fire at Mann Gulch.” Harvard Business School Case Study No. 9-304-037; Roberto, M. and E. Ferlins (2005). “Storm King Mountain.” Harvard Business School Case Study No. 9-304-046. In addition, Bryant University student Taryn Beaudoin recently completed her senior honors thesis under my supervision. She and I conducted extensive field research at GameWright, an award-winning games company located in Newton, Massachusetts. Her thesis is a case study of the firm. It focuses extensively on how managers at the firm employ intuition to make critical choices about which games to develop and produce. See Beaudoin, T. (2008). “Creativity, intuition, and product development: A case study of GameWright, Inc.” Unpublished thesis. Smithfield, RI: Bryant University.

6 Neustadt, R. and E. May. (1986). Thinking in Time: The Uses of History for Decision-Makers. New York: Free Press.

7 Ibid, p. 49.

8 For more on the swine flu incident, see Warner, J. “The Sky is Falling: An Analysis of the Swine Flu Affair of 1976.” http://www.haverford.edu/biology/edwards/disease/viral_essays/warnervirus.htm.

9 Neustadt, R. and E. May. (1986). p. 56.

10 Neustadt, R. and E. May. (1986). p. 54.

11 For faculty members interested in teaching a case study about the swine flu incident, see Neustadt, R. (1993). “Swine Flu Scare in America (A).” Harvard University John F. Kennedy School of Government Case Study No. KSG1053.0. Professor Neustadt and others have produced a number of other case studies about the swine flu incident as well.

12 Gavetti, G., and Jan Rivkin. (2005). “How Strategists Really Think: Tapping the Power of Analogy.” Harvard Business Review. April: 54–63. Gavetti and Rivkin had published a stream of work on how firms use analogies to formulate competitive strategy. For instance, see the following articles: Gavetti, G., D. Levinthal, and J. Rivkin. (2005). “Strategy-Making in Novel and Complex Worlds: The Power of Analogy.” Strategic Management Journal. 26(8): 691–712; Gavetti, G. and J. Rivkin. (2004). “Teaching Students How to Reason Well by Analogy.” Journal of Strategic Management Education. 1(2).

13 Abelson, J. “High-concept cleaners in tatters.” Boston Globe. May 15, 2008.

14 For an interesting history of how Staples was created, see Stemberg, T. (1996). Staples for Success: From Business Plan to Billion-Dollar Business in Just a Decade. Santa Monica, CA: Knowledge Exchange.

15 Interview with T. Krasnow, founder and former chief executive officer of Zoots. Krasnow and I worked at Staples together at the same time, although I was only a project manager working on acquisition integration efforts while Krasnow served as executive vice president of marketing. When I was teaching at the Harvard Business School, Krasnow was kind enough to come back and speak with some of my students about his professional experiences at Staples and Zoots. He also granted me an interview to talk about Zoots soon after he stepped down as chief executive officer.

16 Abelson, J. (2008).

17 Carroll, G. and G. Powell. (2003). “Cocoa Pete’s Chocolate Adventures.” Stanford Business School Case Study No. E153.

18 Ibid.

19 For a superb scholarly examination of the Enron collapse, see Salter, M. (2008). Innovation Corrupted: The Origins and Legacy of Enron’s Collapse. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Mal Salter also has produced a case study that instructors might want to use when teaching about the Enron collapse. See Salter, M. (2003). “Innovation corrupted: The rise and fall of Enron (A) and (B).” Harvard Business School Case Study No. 904-036.

20 This section is based on interviews I conducted at Enron with David Garvin, Joseph Bower, and Lynne Levesque of Harvard Business School in 2001 before the firm entered bankruptcy.

21 Neustadt, R. and E. May. (1986). p. 39.

22 Ibid.

23 Neustadt, R. and E. May. (1986). p. 36. See also Truman, H. (1955–1956). Memoirs. Volume II. New York: Doubleday. pp. 332–333.

24 Neustadt, R. and E. May. (1986). p. 43.

25 Neustadt, R. and E. May. (1986). p. 44.

26 For more on Truman’s decision-making with regard to the Korean War, see McCullough, D. (1992). Truman. New York: Simon and Schuster. I also learned a great deal about President Truman’s leadership and decision-making style when David McCullough came to Bryant University to deliver a speech about the American presidency on April 24, 2008.

27 For more on active listening, with a particular emphasis on health care applications, see Robertson, K. (2005). “Active listening: More than just paying attention.” Australian Family Physician. 34(12):1053–1055. In addition, see the following articles: Phelan, T. (1994). 1-2-3 Magic: Effective Discipline for Children 2–12. Glen Ellyn, Illinois: Child Management Inc.; Korsgaard, M., D. Schweiger, and H. Sapienza. (1995). “Building commitment, attachment, and trust in strategic decision-making teams: The role of procedural justice.” Academy of Management Journal. 38(1): p. 60–84.

28 For an article on how to deal with blame effectively, see Baldwin, D. (2001). “How to win the blame game.” Harvard Business Review. July/August: 55–60.

29 Interview with Mario Shiliashki, Director of Finance, PayPal. Note that PayPal is a subsidiary of eBay, where I learned about another interesting story of pattern recognition. Nearly a decade ago, I had the opportunity to have breakfast with eBay CEO Meg Whitman, along with a few of my faculty colleagues. Whitman recounted an interesting story of pattern recognition to me at that time. She described how the firm tried to identify patterns in the buying and selling of goods on the site. She told us of a young manager who had noticed that a small market for used cars seemed to be emerging on the auction site in 1999. That manager also recognized the constraints that limited the potential of this market. For instance, most buyers wanted some sort of third-party endorsement of the quality and safety of the vehicle. Thus, the manager arranged inspection services to help reassure prospective buyers. This service and others like it helped create a much more viable market, and eBay’s automobile sales took off. As it turns out, this manager was Simon Rothman, a classmate of mine from Harvard Business School who sat next to me for the second half of my first year in the MBA program!

30 These thoughts on the case method benefit greatly from my conversations with many students over the years at Bryant University, New York University’s Stern School of Business, and Harvard Business School.

31 Former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara shared these thoughts with me when he visited my class at the Harvard Business School in the spring of 2005.