2. Circumvent the Gatekeepers

“Bad news isn’t wine. It doesn’t improve with age.”

—General Colin Powell

On November 21, 1970, fifty-six American soldiers conducted an audacious raid on the secluded Son Tay prisoner of war (POW) camp, deep in the heart of North Vietnam. The planning of the operation began in May of that year, when reconnaissance imagery showed evidence of soldiers being held captive at Son Tay. One intelligence official noted, “What really grabbed our attention was another pile of rocks that had been laid out in Morse code that said there were at least six men in that prison who were going to die if they didn’t get help fast.”1

Special-operations forces trained rigorously for this mission, rehearsing a remarkable one hundred seventy times in the months leading up to the raid. The rehearsals attempted to mimic the actual conditions at Son Tay, with live-fire exercises conducted at a mock-up of the camp that was constructed at a Florida military base. U.S. Air Force personnel logged more than one thousand hours of flying time in preparation for the mission, which called for dangerous low-altitude flying by MC-130 aircraft under radio silence. Meanwhile, the U.S. Navy prepared exhaustively for an extensive diversion that they created in Haiphong Harbor on the night of the raid.

President Richard Nixon ultimately approved the mission, and the raid took place in November. The special-operations forces executed their plan with remarkable precision. The soldiers landed at the camp in the middle of the night, ready to free the seventy POWs believed to be located there. Despite the danger, no soldiers died during the raid, and only two suffered injuries. In fact, the forces killed more than one hundred enemy troops—actually Russian and Chinese advisors located at a training school adjacent to the camp. However, when the special-operations forces searched the compound, they found no POWs. The North Vietnamese had moved the prisoners prior to the raid. The incident, despite the heroic efforts of the special-operations forces, became an embarrassing example of flawed intelligence leading to faulty decision-making.

Decision-making regarding the Son Tay raid took place at the highest levels of the U.S. government. Brigadier General Donald Blackburn gave the green light for the planning and training to take place. Admiral Thomas Moorer, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird reviewed and approved the plans. By late summer, though, imagery seemed to show decreased activity at the camp. Nevertheless, preparations for the raid continued.

In late September, Laird briefed President Nixon on the mission, who seemed to favor the idea. Laird informed Nixon about recent images that indicated decreased activity at the camp, while noting that experts continued to seek better photographs. As it turned out, many additional attempts to secure reconnaissance images during the autumn months proved unsuccessful. During this time, the planners lamented that they did not have human intelligence about the camp.

After their meeting, Nixon asked Laird to review the plans with National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger, which he did in early October. At that meeting, Kissinger asked about the risks. General Blackburn offered him a “95 to 97 percent assurance of success.”2 In his memoirs, Kissinger points out, “We knew the risk of casualties, but none of the briefings that led to the decision to proceed had ever mentioned the possibility that the camp might be empty.”3

Finally, on November 18, Admiral Moorer and Secretary Laird met with Nixon to secure his final approval. At this meeting, Moorer and Laird did not bring up the evidence of decreased activity in the most recent photographs from late summer. Nixon gave the green light, hoping to free the prisoners and secure a boost in public support for the war and his administration. He also wanted to gain leverage at the negotiating table by showing that the U.S. could stage a successful raid deep in enemy territory. Impressed by the extensive preparations that had been done, Nixon declared, “How could anyone not approve this?”4 When Moorer mentioned that the operation would be canceled at the last minute if any signs indicated that the North Vietnamese had become aware of the operation, the President replied, “Damn, Tom, let’s not let that happen. I want this thing to go.”5

Soon after this fateful meeting, General Blackburn received word that a North Vietnamese human-intelligence source had reported to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) that no prisoners remained at the Son Tay camp. They had been moved to another site. The source, a North Vietnamese bureaucrat, had worked with the U.S. for more than a year and had proven quite reliable. However, the CIA did not disclose this source to General Blackburn and his staff during the many months in which they had been planning the raid. The CIA only asked the bureaucrat about Son Tay in the days just prior to the mission, after they learned that the planners had been unable to secure high-quality imagery of the camp recently.6

When Blackburn received word about the source, he launched into a reassessment of the situation. Over the next twenty-four hours, he conferred with Laird, Moorer, and Lieutenant General Donald Bennett—the head of the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA). Blackburn still wanted to go ahead, but he did not know what to make of the contradictory intelligence. He noted, “One minute they were ‘sure’ the prisoners were gone, the next they were ‘suspicious’ that POWs had been moved back into Son Tay.”7 In a key meeting on November 20, Bennett provided roughly equal amounts of evidence both for and against the conclusion that prisoners remained at Son Tay. In the end, though, Bennett agreed that the mission should go ahead, in part based on Blackburn’s assurances of success. Laird and Moorer decided to proceed as scheduled on November 21. Interestingly, Laird did not notify the White House about the human intelligence that had surfaced and the debates that had ensued among the mission’s planners. An assistant to Moorer commented that Nixon “didn’t want to know” about contradictory information at that point. Laird later said that he did not find the human intelligence credible, so he chose not to pass it along to the president.8

The story of the Son Tay raid highlights a very important challenge for leaders in all organizations. People at various levels in the organizational hierarchy filter information for various reasons. They do not pass along all the data they have received or collected. Instead, they make judgments about what information is required by their leaders to make key decisions. Leaders know that filtering takes place, and to some extent, they welcome it. After all, they do not want to become overwhelmed with data; they want their advisors to synthesize and analyze key information for them. However, leaders should worry that they may be shielded from key problems by this filtering process. Without question, the most extensive filtering tends to take place with regard to bad news, disconcerting information, and data that contradict the senior leaders’ preestablished viewpoints or positions on a particular issue.

Consider the filtering that took place with regard to the Son Tay incident, and the way in which the president’s behavior encouraged that filtering to take place. The CIA chose not to pass along information about its human-intelligence source until the last minute. The agency sat on that information for months. Secretary of Defense Laird chose not to inform the president of the new information from that source indicating that the prisoners had been moved to another camp. That filtering of new information took place despite the fact that, for many weeks, the planners had expressed disappointment at the lack of human intelligence on the camp. The planners finally had the information that they craved for so long, yet they deemed it unreliable and chose not to pass it along to the White House. Through it all, Nixon chose not to probe deeper when given information that some recent imagery showed reduced activity at the camp. He made it very clear that he wanted to move forward with the mission, and he stated quite firmly that he would be disappointed if they had to cancel the operation. In short, Nixon’s enthusiasm for the mission seemed to discourage subordinates from coming forward with the “bad news” regarding the apparent abandonment of the camp. The president certainly never invited his advisors to come forward with any information that would disconfirm their existing view that POWs were being held at that location. He did not tell his advisors to filter out bad news, but he certainly did not create an atmosphere that welcomed discordant information. In sum, the Son Tay incident provides a vivid example of both the dangers of filtering and the leadership behaviors that can encourage the suppression of information about key problems—the bad news that no one seems to want to hear.

Why do people filter information, as Secretary Laird did in the Son Tay case? The reasons range from well-intentioned behaviors meant to help the leader to self-interested behaviors designed to advance one’s own agenda.

First, individuals choose to summarize and package information for senior leaders for the sake of efficiency. They have a limited amount of time to spend with top executives, and they must use that time wisely. Senior leaders have asked for assistance in decision-making; they want to see key data presented, synthesized, and analyzed. In some cases, they want to see the pros and cons of various options. In others, they also want their subordinates to recommend a course of action that should be chosen. Individuals have to make tough choices about what information should be presented in the limited time frame available. “Face time” with senior leaders becomes a precious commodity, and no one wants to squander it by inundating them with information that is not organized and analyzed properly. Neither leaders nor subordinates want to spend time on information that is irrelevant or unreliable. Busy schedules and crowded meeting agendas certainly exacerbate the amount of filtering that takes place. Given the fast pace within most organizations, individuals know that they must get to the point in meetings.9

Individuals also do not know want to waste senior leaders’ time with problems that they believe can and should be solved without executive assistance. Many people fear that they will appear weak or, worse yet, incompetent if they bring a problem to a higher level in the organization. They dread being asked why they could not resolve the issue on their own, or why they are “wasting leadership’s time” on issues that appear to be insignificant.

Individuals also filter information when a group of senior leaders has arrived at an apparent consensus fairly quickly. In those cases, individuals may feel pressure to conform to the majority viewpoint.10 At that point, one may not want to introduce information into the discussion that unsettles or challenges the dominant perspective. Subordinates often do not want to be perceived as rabble-rousers, intent on upsetting the apple cart at the final hour.

Leaders create pressures for conformity whenever they foster the impression that they have already made up their mind. If they stop demonstrating a genuine curiosity and a desire to learn more about a situation, they encourage filtering of discordant information. In the Son Tay case, Nixon signaled very strongly that he would like to proceed with the mission. He did not seem concerned when told that the later images showed decreased activity at the camp. People involved in the White House meetings indicated that he did not seem curious to know why that was the case. Moreover, when Admiral Moorer said that he would recommend canceling the mission if new information arose suggesting that the secrecy of the operation had been compromised, Nixon replied, “Damn, Tom, let’s not let that happen. I want this thing to go.”11 In short, he signaled very strongly that he did not want additional information that might cause reconsideration of the decision to proceed.

When a leader seems to have his or her mind made up, subordinates make a rational calculation with an eye toward future decisions. They want to have an opportunity to influence future choices; they do not want to lose a seat at the table. To preserve access, power, and influence, individuals determine when senior leaders no longer want to hear about additional information pertaining to the decision at hand. At that point, subordinates trade off a possible reduction in quality of the current choice for the maintenance of their role in future decision-making processes.

Filtering sometimes takes place in a rather unconscious manner. Psychologists have shown that human beings tend to process information in a biased manner. We tend to seek out information that confirms our existing views and hypotheses, and we tend to avoid or even discount data that might disconfirm our current positions on particular issues. Psychologists describe this tendency as the confirmation bias.12

We do not always sense that we have assimilated information in a biased manner. Moreover, we enact this bias in a variety of fashions—some more direct than others. Clearly, we may act in a biased manner in our own personal efforts to gather and analyze data. We also might invite certain people to meetings, and not invite others, based on an inclination as to what those people believe. However, the confirmation bias may play out in more subtle ways too. For instance, we may call on people in a certain order in a meeting, such that momentum clearly builds for a particular option through the repeated presentation of data that bolster the preferred alternative. We may even arrange seating in a conference room such that people who are believed to hold disconfirming information do not have the opportunity to sit next to the key decision-maker(s). The lack of physical proximity may send a strong signal about power relationships and thus discourage the bringing forth of information that does not confirm the existing view of the world within that room.

Kissinger apparently recognized that confirmation bias affected the decision-making process in the Son Tay incident. In his memoirs, he wrote, “A President, and even more his National Security Adviser, must take nothing on faith; they must question every assumption and probe every fact. Not everything that is plausible is true, for those who put forward plans for action have a psychological disposition to marshal the facts that support their position.” [emphasis added]13

Filtering naturally may occur for purely self-interested reasons in some cases. Advocates for a particular position may provide information in a manner designed to bolster their recommendation and persuade others to support them.14 At the same time, they may withhold information that highlights the risks and costs of their proposed course of action. To his credit, Lieutenant General Bennett did not do this when offering his intelligence assessment to Blackburn, Moorer, and Laird in that final meeting before the Son Tay mission began. Instead, he offered a balanced view, with apparently equal amounts of data both in support of and against going ahead. However, Blackburn clearly seemed to tilt his presentations throughout the process in favor of moving forward with the mission. Laird, too, became a strong advocate for the operation, rather than an unbiased evaluator of the mission’s benefits and risks. While he had informed Nixon of the evidence of reduced activity at the camp in prior meetings, he did not bring that data forward again when asking the president for final approval to proceed with the operation on November 18. Of course, Laird also did not go back to the president with the human intelligence.

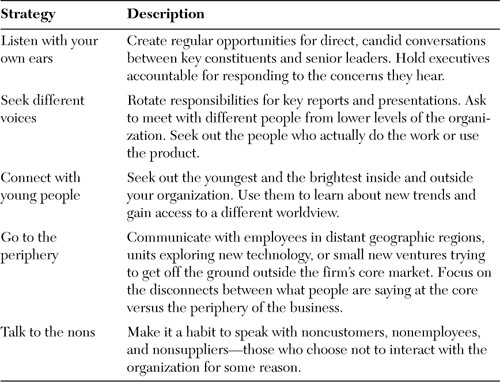

If leaders hope to uncover key problems in their organizations before they mushroom into large-scale failures, they must understand why subordinates may choose to filter out bad news. They must be wary of how their own behavior may cause their advisors to hold back dissonant information. Leaders clearly must create a climate in which people feel comfortable coming forward with new data, even data that might go against the dominant view in the organization. To become effective and proactive problem-finders, though, leaders must go one step further. From time to time, leaders must circumvent the filters by reaching out beyond their direct reports to look at raw data, speaking directly with key constituents, and learning from those with completely different perspectives than their closest advisors. In short, leaders need to occasionally “open the funnel” that typically synthesizes, packages, and constricts the information flow up the hierarchy. They have to reach down and out, beyond the executive suite and even beyond the walls of the organization, to access new data directly. They have to find information that has not been massaged and packaged into a neat, slick Microsoft PowerPoint presentation. To do so, leaders must become adept at five techniques shown in Table 2.1.

These activities may take some time amidst an already very busy schedule for senior executives, but the investment will pay off handsomely if it enables leaders to spot threats, as well as opportunities, at a very early stage.

Anne Mulcahy took over as CEO at Xerox on August 1, 2001. She became CEO at a time when the organization was in deep trouble. Losses had mounted, the sales force seemed dispirited, and the debt burden was overwhelming. A Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) investigation ultimately led to a restatement of earnings going back to 1997. The specter of bankruptcy loomed. Over the past seven years, Mulcahy has engineered a remarkable transformation. She has reconfigured and enhanced the company’s product line, enhanced customer service, and returned the company to a sound financial position.15

Mulcahy has taken some interesting steps to ensure that she and her fellow senior executives receive unfiltered information about customer satisfaction and dissatisfaction. She has chosen to listen directly to them, without a go-between who might alter or muddy the message. Specifically, Mulcahy employs two techniques to circumvent the usual filtering process that shapes the customer-service data that reach senior leaders. Her techniques involve more than simply going out on customer visits, although she does that as well. First, Mulcahy has assigned each of the company’s top five hundred customers to a member of the top management team. Interestingly, she has not assigned accounts only to executives in charge of functions such as sales, marketing, and operations. She explains:

“All our executives are involved—including our Chief Accountant, our General Counsel and our head of Human Resources. Each executive is responsible for communicating with at least one of our customers, understanding their concerns and requirements and making sure the appropriate Xerox resources are marshaled to fix problems, address issues and capture opportunities.”16

Secondly, Mulcahy has created a program whereby each member of the top management team serves as a “Customer Officer of the Day” at corporate headquarters on a monthly basis. She wants to hear the unvarnished comments from customers who may be having problems with the firm’s products. Moreover, Mulcahy wants each member of the top team, including herself, to be personally accountable for addressing customer concerns. She describes the program:

“There are about 20 of us and we rotate responsibility to be ‘Customer Officer of the Day.’ It works out to about a day a month. When you’re in the box, you assume personal responsibility for dealing with any and all customer complaints, that come in to headquarters that day. They are usually from customers who have had a bad experience. They’re angry. They’re frustrated. And they’re calling headquarters as their course of last resort. The Xerox ‘Officer of the Day’ has three responsibilities—listen to the customer, resolve their problem and assume responsibility for fixing the underlying cause. Believe me, it keeps us in touch with the real world. It grounds us. It permeates all our decision making.”17

Mulcahy’s initiatives create direct communication between frontline users of her products and senior executives. She does not simply rely on summaries of statistics about customer service. The conversations with customers become valuable raw data that may provide insights not available in reports compiled from reams of customer survey statistics. Mulcahy has learned that customer questionnaires can be deceiving. People may report that they are “satisfied” with a company on a survey, yet still remain quite likely to switch to another firm’s products. Mulcahy describes this phenomenon:

“There has been a norm around for many years that somewhere around 75 per cent of customers who defect say they were ‘satisfied.’ Our own research bears this out. When our customers tell us they are ‘very satisfied,’ they are six times more likely to continue doing business with us than those who are merely satisfied... If you’re just providing your customers with service that’s good, they’re probably just satisfied. This should set off alarm bells. Take the automotive industry. Satisfaction scores average around 90 per cent. Guess how many people repurchase from the same manufacturer? Only 40 per cent.”18

CVS is another company that has found ways for senior executives to access unfiltered information about customer service. In the past, the company relied on mystery shoppers to evaluate service in each of its store locations. Today, CVS has a program called Triple S, which stands for stock, shop, and service. Are the products that customers want in stock? Are the stores neat, clean, and uncluttered? Are the store associates courteous, helpful, and professional, and are wait times minimized? The company measures the three Ss using a customer questionnaire. People who shop at CVS occasionally receive a receipt for their purchases that contains an invitation to call a toll-free number and respond to a set of survey questions. Customers who respond become eligible for a cash sweepstakes that takes place each month. Today, CVS receives more than one million responses per year from its customers. The company finds that a store’s sales performance is correlated with its Triple S score.

Interestingly, though, CVS does more than simply compile Triple S scores for each of its stores. Executives do not only look at reports filled with analysis of the data. Helena Foulkes, Senior Vice President of Marketing, explains that the calls are recorded, and that executives can listen to actual comments for a particular store that appears to be struggling. Moreover, CVS has enacted a “Customer Comment of the Day” program for its senior leadership team. Each day, the top ten executives at CVS receive an electronic audio file of one phone call received the prior day from a customer. That comment can be either positive or negative. A senior manager typically selects this call to distribute to the top team because it highlights something new or intriguing that they may not have considered or heard previously. Foulkes finds some of these comments to be incredibly thought-provoking. Finally, similar to Xerox, each senior team member takes calls from customers for one hour roughly twice per year. Foulkes points out that these recorded and live phone calls are “deeply personal” experiences. They shed insights in a way that quantitative data sometimes do not. She also points out that they provide a perspective that an executive cannot achieve simply by shopping in or walking the firm’s stores. Foulkes explains that, “The way that you shop as a retailer is quite different than the way that your customers shop.” As a result, executives and customers experience the stores in distinct ways. It proves difficult to see the stores through a customer’s eyes. Foulkes stresses that listening to the Customer Comment of the Day and taking phone calls personally enables executives to hear about problems firsthand, to spot patterns and trends quickly, and to avoid becoming isolated in the executive suite.19

In 2005, David Tacelli became the CEO of LTX Corporation, a producer of semiconductor test equipment located in Norwood, Massachusetts. Tacelli has implemented a rigorous customer review system to review the company’s major accounts on a regular basis. He aims to “surface customer service problems early” through this routine evaluation process. He has learned, though, that the system can become stale if the same senior manager reports on a particular customer at each review meeting. As he says, “They tend to filter. They think that they can fix the problem. Therefore, they do not tell anyone until far too late.”20 Therefore, Tacelli makes sure that everyone involved with a particular client presents over time at these review meetings. He explains:

“I rotate presenters very purposefully. If a problem surfaces at a particular meeting, I will go back to the person that presented at the previous meeting. I ask them if they were aware of the issue at the time of their presentation. If so, then I probe as to why they did not surface the issue sooner. The key is for them to learn from the experience and not make this an exercise to assign blame. I’m trying to teach them to communicate openly about issues so we can solve them more effectively. Of course, I do look for patterns of mistakes from people who present. If someone repeatedly holds back information, then I need to solve a different problem with that individual, because in the end, they need to know that they will be held accountable.”21

Tacelli asks his managers to limit the number of slides they present at these meetings. He says, “I want them to talk with me and one another, not to read off of slides.” He explains that his role is to “play Jeopardy with them...to use the Socratic method to find out what the key issues are, to see what we know about the causes of particular customer complaints.”22

Larry Hayward seeks different voices over time as well. Hayward, a business unit general manager at Ametek Corporation, makes customer visits on a regular basis, as many executives do. However, Hayward makes it a point to speak not only with the people at the client location with whom he normally communicates by phone or email. He seeks out others in the purchasing department with whom he typically does not interact. Much more importantly, he does not restrict himself to the procurement unit. Hayward reserves time to meet with engineers, who use his firm’s products on a daily basis, as well as others in various areas of the client organization. He wants to collect a variety of perspectives on his organization’s products and customer service. Hayward also does not restrict himself to senior managers. He wants to speak with frontline engineers who have firsthand knowledge about the use of his firm’s products.23

Peni Garber serves as a partner at ABRY Partners, a Boston private-equity firm specializing in the media and communication industries. She applies this same logic to her investments in various companies. When Garber visits companies that are in her investment portfolio, she makes it a point to not restrict her conversations to the CEO and other board members. Garber seeks out information from a variety of managers within the portfolio company. She does so for three reasons. First, she wants to assess the talent within the firm. Second, these conversations help her test for organizational alignment. Does everyone understand the strategy? Has senior leadership achieved strong buy-in at all levels? Do people share a common set of values? Finally and perhaps more importantly, she hopes to discover if issues are festering beneath the surface, about which the CEO and board may be unaware, or have chosen not to disclose fully to the investors. In most cases, like Tacelli at LTX, she finds that executives do not mean any harm when they hold back bad news. They believe that they can solve the problem on their own, if only they had a bit more time. They do not want to waste the investors’ time with an issue that they believe can be solved quite readily.24

Young people often have a keen early understanding of important societal trends. They tend to have great familiarity with the latest ideas and products in fields such as technology, fashion, healthy living, and the environment. For that reason, Gary Hamel argues that CEOs should go out of their way to stay connected with the youngest and brightest in their organization. He recommends that CEOs form a “shadow cabinet” of highly capable employees in their twenties and thirties. The CEO should then meet with this cabinet periodically to see how their perspective on key strategic issues differs from what he or she is hearing from the members of the senior management team. Hamel believes that interacting with young people will help CEOs see opportunities and threats that senior leaders may not perceive. Moreover, Hamel recognizes that the perspectives of these young people often are filtered out if left to the normal machinations of the organizational hierarchy.25

General Electric went one step further during the e-commerce revolution of the mid- to late 1990s. One business unit president in London recognized that he did not understand the Internet as well as he should have. He wanted to get up to speed on the business. Therefore, he found the brightest young person under the age of thirty in the organization, and he asked that employee to serve as his mentor on e-commerce issues. The talented young person spent the next several months schooling the head of the business. When Jack Welch heard about this technique, he asked all the general managers at General Electric to find young mentors who could teach them the ins and outs of the web. As Welch said, “we turned the organization upside down. We had the youngest and brightest teaching the oldest.”26

Today we find many business leaders tapping into the perspectives and ideas of young people through technology. A variety of innovations have provided a fast and economical way for senior executives to connect with young people on the front lines of their organizations. Many CEOs have blogs, and some have begun to spend time trying to understand, in a systematic manner, what their employees are writing on their own blogs. At Hewlett-Packard, researchers have created new technology that analyzes what is being written on the blogs of more than ten thousand employees. The technology, termed WaterCooler, aims to identify key issues being discussed in a particular time period, as well as patterns of comments over time. The name for the software came from the notion that it provides an ability to listen in, with permission, on the many virtual water cooler conversations that employees are having in cyberspace.27

Some CEOs have ventured onto Facebook and MySpace to interact with their younger employees. Paul Levy, CEO of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, has created a Facebook page. He has over four hundred friends in a social group that he has created, many of whom are his employees. He comments, “It’s fun, a nice way to communicate with a group of people who might not otherwise interact with me.”28 Similarly, Tom Glocer, CEO of Thomson Reuters, spends time on Facebook. Some in the British press have criticized him for spending his time in such a manner. He offers a rebuttal—on his blog, of course:

“Now it could be argued, I suppose, that imagination and experimentation should be left to more junior or younger staff, and the chief executive should only perform ‘serious’ duties like strategy formulation and ordering people around. I think this is a lousy and disconnected way to lead. I believe that unless one interacts with and plays with the leading technology of the age, it is impossible to dream the big dreams, and difficult to create an environment in which creative individuals will feel at home...I believe it is a very worthy investment of my ‘free’ time to explore the latest interactions of media and technology.”29

Andy Grove, longtime chairman and CEO of Intel, argues that senior executives must reach out to the periphery of the organization if they want to see threats and opportunities at a nascent stage. By the periphery, he means distant geographic regions, units exploring new technology, or small new ventures trying to get off the ground outside the firm’s core market. Grove explains:

“Think of it this way: when spring comes, snow melts first at the periphery, because that’s where it’s most exposed... In the ordinary course of business, I talk with the general manager, with the sales manager, with the manufacturing manager. I learn from them what goes on in the business. But they will give me a perspective from a position that is not terribly far from my own. When I absorb news and information coming from people who are geographically distant or who are several levels below me in the organization, I will triangulate on business issues with their view, which comes from a completely different perspective. This will bring insights that I would not likely get from my ordinary contacts.”30

In his latest research, Joseph Bower argues that chief executives may even find highly capable successors at the periphery of their organizations.31 Bower reconsiders the notion of hiring an insider versus an outsider as the new chief executive. An insider offers the benefit of a wealth of experience in the business and a deep understanding of the firm’s culture and values. However, insiders may be too tightly wedded to a particular mental model of how to do business. That cognitive inflexibility might not serve the firm well if it experiences a major shift in the external environment. Outsiders clearly bring a fresh perspective, but they may not always have the adequate experience or fit the firm’s culture.32 Bower notes that many successful succession processes involve the hiring of an executive who has spent extensive time at the periphery of the organization, working in foreign markets, new ventures, and the like. In so doing, they have developed fresh perspectives and perhaps even come to question some of the central tenets held by those who work at the core of the business. Bower describes these individuals as inside-outside leaders, and he argues that they bring a more objective perspective on the changes needed in the mainstream business when they become chief executive. In so doing, they combine the benefits of being an insider with the divergent perspective of an outsider.

Many executives spend time talking with their current customers, employees, and suppliers. How many speak on occasion with their noncustomers, nonemployees, and nonsuppliers—those who are currently not engaged with their organization in some fashion? Connecting with these groups can provide incredible insight. Clayton Christensen argues, for instance, that spotting disruptive innovation opportunities tends to happen when one speaks with noncustomers as opposed to current users. The latter group often focuses on incremental improvement ideas for your current product line, rather than a truly breakthrough change.33 Likewise, speaking with applicants who have turned down a job offer from your company may tell you a great deal about how and why you can attract and retain talent more effectively. You may even go so far as to talk with university students who have attended an information session held by your firm, but then chose not to submit a job application. What did they hear or learn that caused them to look elsewhere for employment?

Universities spend a great deal of time speaking with those who choose not to become their students, and they learn an immense amount from them. Without question, every college obsesses about its admissions yield—the percentage of accepted students who choose to matriculate at the school. Yield represents a critical measure of a school’s attractiveness. Moreover, poor yield prediction can have pernicious consequences for a university. A lower-than-expected yield leads to empty dorms and the associated drop in revenue, while a higher-than-expected yield causes overcrowding and perhaps subsequent student dissatisfaction. Universities spend time trying to speak with accepted students who chose to enroll elsewhere. They ask many questions. What other schools did they select most often? Why did they choose those schools? What types of students are most likely to not enroll? The systematic analysis of these answers often proves illuminating, and it leads to enhancements both in the admissions process and the university as a whole in the years to come. Like these schools, business leaders can benefit by speaking with those who have rejected their organization. But don’t leave this task to only your customer-service personnel or human-resources managers. Senior leaders need to occasionally hear from these voices directly. They need to hear the unvarnished truth from those who have chosen not to engage with the organization for one reason or another.34

Is finding a way to circumvent the filters truly valuable? Can it really help leaders see the future, to spot problems before they mushroom into catastrophes? To close this chapter, consider for a moment the remarkable career of Winston Churchill. Many people marvel at how prescient he was at key moments in his lifetime. He seemed to see looming threats long before others did. Time after time, he tried to sound the alarm about threats to his beloved Britain, and he recommended preparatory measures. Churchill foretold the threat from rising German militarism in the years prior to World War I. Similarly, he tried to sound alarms about the threat from Hitler during the 1930s, but sadly, his warnings fell on deaf ears for far too long. Finally, he predicted the threat from Soviet expansionism, culminating in his famous Iron Curtain speech in March 1946.

How did Churchill cultivate this ability to spot the threats and problems that loomed ahead? One reason may be that he immersed himself in each job he held in the British government. He did not spend his time huddled in London with only his closest advisors. Churchill always wanted to be in the thick of the action. He traveled relentlessly to speak with people far and wide, from inside and outside government. He demonstrated a remarkable inquisitiveness and curiosity, and he loved speaking with the people on the front lines. Some characterized him as reckless at times; he even wanted to observe the D-day landings firsthand from a naval vessel in June 1944. General Eisenhower and King George VI intervened to keep him from doing so for safety reasons. Nevertheless, Churchill’s desire to see and hear things firsthand served as an asset far more than a liability.

Consider what happened when Churchill became First Lord of the Admiralty in 1911. He set out to understand the scope of German military superiority and to revolutionize the British Navy in preparation for war. During this time, he launched a massive construction campaign and switched the British fleet from coal to oil—momentous decisions that met with a healthy dose of skepticism at the time. He also equipped his ships with 15-inch guns, an innovation that proved critical during the combat that soon unfolded.

Churchill came to these decisions after engrossing himself in all facets of the British Navy. He engaged in a whirlwind of activity:

“With the Admiralty’s yacht, the Enchantress, as his home and office, he mastered every detail of navy tactics and capabilities. He appeared to be everywhere at once, inquiring, badgering, learning. He was interested in everything from gunnery to the morale of his soldiers. He was fascinated with airplanes and immediately understood their utility for warfare. He spent hundreds of hours learning how to fly. He crawled into the cramped quarters of gun turrets and learned how they worked. It became his practice to solicit information and opinions from junior officers and ordinary seamen, often ignoring or arguing with their superiors. The respect he showed them, and the increases in pay he won for them, made him a favorite in the ranks.”35

Churchill could get into trouble at times. His senior naval officers often did not like the fact that he asked sailors to tell him what their superiors were doing wrong. They believed that he was inviting insubordination. Without question, Churchill could have taken more care in how he gathered unfiltered information from the ranks. Nevertheless, his behavior proves instructive for us today. Churchill understood that the constriction of information that takes place in any hierarchy can be stifling—even dangerous. He understood that a leader’s greatest assets sometimes are his own eyes and ears. One’s closest advisors may certainly provide sound counsel in trying times, but they also may insulate a leader from the hard truths, unwelcome news, and lurking dangers that could imperil a business. Sometimes, leaders need to walk outside without an umbrella and feel the raindrops on their skin.

1 Amidon, M. (2005). “Groupthink, Politics, and the Decision to Attempt the Son Tay Rescue.” Parameters: U.S. Army War College Quarterly. 35(3): 119–131. For more information on the Son Tay raid, see Schemmer, B. F. (2002). The Raid: The Son Tay Prison Rescue Mission. New York: Ballantine Books.

2 Amidon, M. (2005).

3 Kissinger, H. (1979). White House Years. Boston: Little Brown. p. 982.

4 Amidon, M. (2005).

5 Amidon, M. (2005).

6 The failure to share information freely among agencies of the federal government represents a recurring issue in American history. As noted in Chapter 1, a lack of information-sharing contributed to the government’s failure to prevent the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. We will explore the circumstances surrounding those attacks in much more depth in Chapter 5. Of course, one should note that many organizations, in both the public and private sector, have “silos” that do not collaborate effectively with one another. The problem may be particularly acute in our intelligence community, but it certainly is not exclusive to those organizations.

7 Amidon, M. (2005).

8 For more on President Richard Nixon’s leadership style, see the following books: Ambrose, S. E. (1987). Nixon. New York: Simon and Schuster; Reeves, R. (2002). President Nixon: Alone in the White House. New York: Simon and Schuster.

9 Heike Bruch and Sumantral Ghoshal wrote an interesting article on the crowded schedules of many managers based on a decade of research on how managers spend their time. They discovered that nine out of ten managers use their time very ineffectively. Only 10% of managers “spend their time in a committed, purposeful, and reflective manner.” They offer strategies for helping managers gain control of their schedules so as to be more efficient and effective. See Bruch, H. and S. Ghoshal. (2002). “Beware the Busy Manager.” Harvard Business Review. February: 62–68.

10 An expansive literature describes social pressures for conformity that arise in groups and organizations. Psychologist Solomon Asch conducted one of the earliest studies that had a major influence on future scholars. See Asch, S. E. (1951). “Effects of group pressure upon the modification and distortion of judgment.” In H. Guetzkow (ed.). Groups, Leadership and Men. (pp. 177–190). Pittsburgh: Carnegie Press. Social psychologist Irving Janis produced a classic study on the pressures for conformity within groups, based on his analysis of presidential decision-making. See Janis, I. (1982). Victims of Groupthink. 2nd edition. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. For some more recent work on conformity pressures, see Epley, N. and T. Gilovich. (1999). “Just going along: Nonconscious priming and conformity to social pressure.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 35: 578–589.

11 Amidon, M. (2005).

12 Peter Wason was one of the pioneers in research on the confirmation bias. For instance, see Wason, P. (1960). “On the failure to eliminate hypotheses in a conceptual task.” Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 12: 129–140. A Stanford study in the late 1970s argued that confirmation bias may explain why people might examine the very same set of mixed evidence on a matter, yet come away with attitudes that are more polarized than at the outset. The authors examined people’s attitudes regarding the death penalty. They found that individuals became even more entrenched in their opinions after examining a mixed set of evidence. They argued that people tended to focus on the information that confirmed their existing attitudes and beliefs, and they dismissed the data that challenged their preexisting beliefs. Thus, attitudes became more polarized. For more on this study, see Lord, C., L. Ross, and M. Lepper. (1979). “Biased assimilation and attitude polarization: The effects of prior theories on subsequently considered evidence.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 37(11): 2098–2109. For a thorough review of research on the confirmation bias, see Nickerson, R. (1998). “Confirmation bias: An ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises.” Review of General Psychology. 2(2): 175–220.

13 Kissinger, H. (2003). Ending the Vietnam War. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 185.

14 David Garvin and I have written an article about dysfunctional advocacy in group decision-making. See Garvin, D. and M. Roberto. (2001). “What you don’t know about making decisions.” Harvard Business Review. September: 108–119.

15 For more on Mulcahy’s turnaround at Xerox, see Kharif, O. “Anne Mulcahy Has Xerox by the Horns.” Business Week Online. May 29, 2003. To read the entire article, see the following URL: http://www.businessweek.com/technology/content/may2003/tc20030529_1642_tc111.htm.

16 Anne Mulcahy. “The Customer Connection: Strategies for Winning and Keeping Customers.” Speech to the Empire Club of Canada. June 10, 2004. For a complete text of the speech, see the following URL: http://www.empireclubfoundation.com/details.asp?SpeechID=3000&FT=yes.

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid.

19 Interview with Helena Foulkes, Senior Vice President of Marketing and Operations Services, CVS Caremark Corporation.

20 Interview with David Tacelli, President and Chief Executive Officer, LTX Corporation.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid.

23 Interview with Larry Hayward, Vice President and General Manager, AMETEK Chemical Products.

24 Interview with Peni Garber, Partner, ABRY Partners, LLC.

25 Hamel, G. (2003). “The quest for resilience.” Harvard Business Review. September: 52–58.

26 Bartlett, C. (2000). “GE Compilation: Jack Welch—1981–99.” Harvard Business School Video No. 300-512.

27 McGregor, J. (2008). “Mining the office chatter.” Business Week. May 19, 2008.

28 Diaz, J. “Facebook’s squirmy chapter.” Boston Globe. April 16, 2008. For more information on Paul Levy’s leadership at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, see the multimedia case study I coauthored with Professor David Garvin. The case provides a detailed account of Levy’s turnaround of the medical center, which was on the verge of collapse when he took over in January 2002. The case proves unique because we collected data on the turnaround in real time by conducting video interviews with Mr. Levy every three weeks or so during the first six months of the turnaround. Those interviews began after only one week of his tenure at the hospital. We also collected hundreds of email communications and tracked press coverage of the turnaround; the case includes many of these documents as well. See Garvin, D. and M. Roberto. (2003). “Paul Levy: Taking Charge of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (A).” Harvard Business School Case No. 9-303-008. In addition, we have written an article about the leadership lessons from this turnaround. Garvin, D. and M. Roberto (2005). “Change through persuasion.” Harvard Business Review. February: 104–112.

29 Reed, S. “Media giant or media muddle.” Business Week. May 1, 2008. For direct access to Glocer’s blog, go to the following URL: http://tomglocer.com/.

30 Grove, A. (1999). Only the Paranoid Survive. New York: Currency/Doubleday. p. 110.

31 Bower, J. (2007). The CEO Within: Why Inside Outsiders Are the Key to Succession Planning. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

32 An extensive literature has debated the merits of hiring insiders versus outsiders as CEOs, and much empirical work has been done. For example, see the following academic studies: Behn, B., D. Dawley, R. Riley, and Y. Yang. (2006). “Deaths of CEOs: Are Delays in Naming Successors and Insider/Outsider Succession Associated with Subsequent Firm Performance?” Journal of Managerial Issues. 18(1): 32–47; Chen, W. and A. Cannella. (2002). “Power dynamics within top management teams and their impact on CEO dismissal following insider succession.” Academy of Management Journal. 45: 1195–2007; Chung, K., R. Rogers, M. Lubatkin, and J. Owens. (1987). “Do Insiders Make Better CEOs Than Outsiders?” Academy of Management Executive. 1(4): 325–331.

33 Christensen, C. (2000). The Innovator’s Dilemma. New York: Harper Collins.

34 This section on university admissions draws upon knowledge gathered from conversations over the years with Michelle Beauregard, Director of Admission at Bryant University, and Kim Clark, former Dean of the Harvard Business School.

35 McCain, J. “Extraordinary foresight made Winston Churchill great.” The Daily Telegraph. March 20, 2008. This article in the London newspaper was an excerpt from a book by John McCain and Mark Salter. See McCain, J. and M. Salter. (2007). Hard Call: The Art of Great Decisions. New York: Twelve Publishing. For more details on Churchill’s leadership style, you may refer to one of the many excellent biographies that have been written. I particularly enjoyed the biography authored by British politician and writer Roy Jenkins several years ago. See Jenkins, R. (2001). Churchill: A Biography. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.