Chapter 3

Laddering Defined

A lot of people in our industry haven’t had very diverse experiences. So they don’t have enough dots to connect, and they end up with very linear solutions without a broad perspective on the problem. The broader one’s understanding of the human experience, the better design we will have.

—Steve Jobs

LIKE MANY PEOPLE, one of my passions is cooking. I love to spend a Sunday afternoon tackling a complex recipe, and my favorites are those you find in magazines such as Cook’s Illustrated. This is because I know that the writers and editors at Cook’s Illustrated have spent countless hours trying every conceivable combination of a recipe to come up with one that works just right. The standard, “proven” techniques that other recipes or cooks advocate are often disproved in the Cook’s Illustrated kitchen. This publication and the people who work for it often take a counterintuitive approach to common thinking. Some of my best, and simplest, recipes come from understanding how they have approached the science of cooking differently—the fact that they have taken a broader stroke and determined how to approach individual components of the entire meal, instead of focusing only on the end goal.

The same is true in regard to the concept of laddering. This approach advocates that we take a different approach than the ones we’ve followed before to truly succeed in the space of marketing and product development.

Before I begin my discussion about laddering’s application in detail, I think it’s important to know how this technique has been discussed previously.

The concept of laddering was originally developed during a time that all products were mass-produced. Prior work in the area of laddering concentrated on what features and functions a product had. We then moved the user out from that “feature, function” list to determine what was most important to the consumer when making the decision to buy the product—and to determine what messages or approach brands should use to sell the product to the consumer.

Remember that mass production assumes that you are building a product—a clock radio, watch, toy, or phone, for example—for the masses as cheaply as possible. Therefore, an item’s features and functions are very important in this environment, because they’re really the only things that distinguish one product or service from another. So to decide whether a consumer would buy or not, it was important to ask, “Are the features and functions the right ones for that specific individual?” The earlier concept of laddering focused on creating the right messaging, not necessarily the right product. The message had to be compelling to make the product as enticing as possible.

Thomas J. Reynolds, a consumer researcher and professor, and Jonathan Gutman, a marketer and professor, developed and introduced laddering in 1988, based on Gutman’s Means-End Theory of 1982. Their approach states that product attributes lead to consequences that generate personal meaning (values) for users. In other words, they worked from the starting point of features to determine which functional and emotional benefits resonate with the consumer.

Consumers who were presented with a set of features and benefits prior to mass customization would opt for the product that best satisfied their emotions and beliefs. They would rationalize the purchase by focusing on the features and functional benefits. These consumers didn’t have the number of choices or the amount of knowledge we have when making a buying decision today.

The process involved in this type of laddering work went something like this:

First, the marketer would ask: “Which feature do you like best about this product?”

The marketer would listen to the answer and then ask about functional benefit. “What does the feature do?”

After getting this response, the marketer would then ask about the higher benefit of the functional benefit; that is, “How does that feature benefit you?”

Finally, the marketer would ask about the higher benefit’s emotional benefit: “How does the feature benefit make you feel?”

Once a feature had been exhausted, marketers would ask the consumer about his or her next favorite feature and its functional, higher, and emotional benefits. The order in which these elements are listed became the hierarchy by which the brand promoted it to the consumer.

To put this into context, think about purchasing a stereo system for your home. A consumer buying this kind of item would consider the features and put them in order of priority. After doing so, the consumer would determine which feature was most important to him or her. In this example, we will assume the CD changer is the highest-valued feature of the stereo system:

| Question | Answer |

| What feature do you like best? | I like the CD changer. |

| What does the feature do? | It allows me to play multiple CDs. |

| How does the feature benefit you? | It means that I don’t have to constantly change out CDs. |

| What does the benefit do for you? | The CDs can just play in the background while I cook dinner or host a party. |

The process is then repeated for the rest of the stereo system’s features and functions based on the consumer’s priority until all are exhausted.

This approach was appropriate once upon a time, when it was crucial to start the process by focusing on features or functions and understanding their place of priority. Sellers essentially said: “I start with what I can do for consumers, what can I mass-produce to meet their needs, and understand what their higher-order needs are in order to sell them the product.”

This worked well for Edward Bernays’s work (see Chapter 1), specifically, to understand how to make a consumer want what vendors could make. And because the seller also controlled the message, advertisers could create this sense of wanting by understanding how to speak to consumers’ higher-order desires. “Want to be cool at your next party? Our stereo system lets you concentrate on your friends and entertaining them while the music you select plays in the background.”

Laddering in a User-Centered World

However, we’ve now moved from a world of mass production to one of mass customization. Our current environment has made the consumer the complicated part of the equation. It’s therefore crucial to understand them and what they want, because their selection of features and functions are numerous—and require very low switching costs.

This is a good opportunity to discuss two fairly well-known quotes about the value of qualitative research techniques such as laddering that are actually misunderstood.

The first comes from Henry Ford, who is credited as having said the following about the creation of the automobile: “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.”

The other is attributed to Steve Jobs about the invention of new products, and it basically says the same thing in a simpler way: “People can’t tell you what they want.”

Although it’s true that both of these statements were uttered by the men noted, their meaning has been somewhat twisted and misinterpreted over the years. I often see these quotes on the signature lines of marketers, designers, or product managers as justification for creating in a vacuum using only their own instincts.

What Henry Ford and Steve Jobs were saying is that the average person doesn’t know how to build a product. This is true, and I agree with both of them on that point. That’s why we have product designers.

We can find good analogy for understanding what you should do in the profession of architecture. When you commission an architect to design a house for you, you tell him or her what you want and then trust that professional to interpret your desires into the drawings of the house. Good architects would meet you in your current space and have you walk through what you like, what you would change, and how you want to use the space differently. From this context, they can interpret what to recommend to you in a new space.

Once the architect creates the plans, he or she would walk you through the newly conceived space. At that point, you can provide a solid reaction to what you like or don’t like about how the plan has been laid out.

What Steve Jobs and Henry Ford were saying is that product designers and marketers must become architects of what consumers want to buy and how they already perceive brands or products. As it was with cars and iPods, consumers may not be able to tell you what to build or precisely how to design a product. However, they can certainly express met and unmet needs (the need to go faster or to have their music more conveniently accessible, for instance). And as both Ford and Jobs knew, the future in product development and innovation will always be in understanding where these unmet needs lead—the white space between the consumer and what technology, products, or services currently do or do not do for them.

To start addressing these unmet needs, you must understand your end consumers on a base level. The only way to do this is to get in front of them and engage them in discussions in the context or environment where they will use your product or consider your brand.

Laddering Understands the Consumer’s Context

We all put on masks and present ourselves in a certain way when we go out into public. But if you opened the drawers in our houses, looked in our pockets, or examined our closets, you would find a very different person—with very different motivation.

This is why I interview people one on one, where they live, work, and play, whenever possible. I “go native” with the consumer to truly understand who that person is and how he or she lives. I have been around the world to spend time with end users in manufacturing plants, grain elevators, high-rise apartments, trailer parks, dairy farms, country clubs, and everywhere in between to make certain I could really get to the core of what a user was telling me.

By getting into the consumers’ space, I can go beyond the needs that they express overtly through spoken words. It’s actually rare that a consumer will say, “I really wish this product would do this.” The best and most effective way to understand your consumers is to experience them in their own environments and using their own technology or devices to survive and navigate their own worlds.

When you begin observing them in their natural environments, you realize that consumers build workarounds to make the tools and products in their lives work more effectively. I have seen sticky notes around computer screens, passwords written in notebooks, chemicals stored dangerously close to each other because they are sorted by task and the dangers are not obvious, and technology devices with added features that make the consumer’s life easier but would definitely void the manufacturer’s warranty.

Consumers create their own elaborate systems to survive and thrive in their daily environments. If the password for a website is too long or difficult to remember, many will just write it down on a sticky note and attach it on the side of the monitor. Other consumers who view this approach as unsafe would never consider doing this; instead, they might write it down in a notebook and keep it in a locked drawer. This tiny difference in keeping up with a hard-to-remember password is a gaping window into the core of each type of person. More important, these workarounds become talking points for analysis and follow-up with the consumer about unmet needs.

I also identify patterns in the core of who people are by viewing them in the context of where they spend their lives. For example, someone may claim to be a neat person and appear as such in public. Yet when you see piles of paper stacked on that same person’s desk and pouring out of their file cabinets, you learn so much more.

The truth is that consumers lie—every single one of us. We don’t do it on purpose; it’s simply part of our human nature to present the best sides of ourselves, even if those portrayals aren’t completely accurate. But understanding the lie and its intent, getting beneath it to uncover the truth, is what helps you truly understand differences in groups of individuals. There are patterns in these lies that marketers can use to hone their messaging and develop the most desirable products. It’s essential to not only speak to who a consumer wants to be but also understand who that person really is.

A prime example of this is couponing and coupon use. We conducted one particular study during the time that Extreme Couponing was popular both as a television show and as a trend. We kept hearing from a group of people who were planning to extreme coupon at some point. Of course, this was merely an aspiration. We ended up calling this group casual couponers—people who would participate in coupons only if they happened upon them. We could tell that they weren’t as serious about couponing based on other contextual cues: how they kept their houses and how they approached other life goals such as weight loss or saving money. All these goals were something this cluster aspired to do, but they just didn’t have the motivation (and more important, the encouragement) to accomplish them. They didn’t have the core DNA necessary to be true extreme couponers.

The same study exposed us to a group of people who had a highly systematic approach to using coupons. They clipped coupons regularly and used them effectively—and this organized approach extended to areas of their life beyond coupon use. But they wouldn’t engage in extreme couponing, because they saw it for what it was: organized hoarding.

The Inadequacy of Focus Groups

I often encounter companies trying to use focus groups or similar methods to get to an underlying understanding of their consumers and determine what products or messages to build for them. Despite their widespread use, focus groups are fraught with issues, for many reasons. They are an overused and, quite frankly, lazy technique to get to the type of information that is necessary for product development and messaging in the new world.

Many companies assume that they’ve recruited a group of “like” people in a focus group, but how do you truly know how alike they are? Just because a certain group shares a demographic characteristic or segmentation, or even if they have bought or might likely buy similar items in the future, isn’t a guarantee that their motivation and core drivers are similar in any way.

Another big danger with focus groups is that many companies skimp on recruiting the right number of groups to ensure accurate patterns. If something happens to your only focus group or even one of the three focus groups you are conducting, you lose all of the data from that group. But if something happens in an individual interview, you lose only the data from that one individual. And no matter how skilled or experienced a focus group moderator is, there are things that can and do happen during focus groups that affect the outcome. You can have an unruly participant, or the moderator may ask a question the wrong way or out of order. Once something like this occurs, you have a much larger problem than the loss of a single interview.

Other limitations are that these groups don’t allow for individual discovery with the participants. You can’t get to the heart of what a participant’s words truly mean, because it’s difficult and awkward to probe them on the root issue in front of others.

The list of drawbacks goes on. There are time limits; it’s an artificial environment; and there is groupthink, dominance issues, and a social pecking order. The very format of a focus group defeats its primary purpose: to get a deep understanding of the individuals in the room. To do that, you need to spend time with each one of them. But if you divide the amount of time spent in a focus group (on average 1½ hours) by the number of participants, you really only “hear” from each participant for about 12 minutes total.

I do believe that focus groups have a place; however, it comes after you’ve completed the proper work to truly understand who the consumer groups are. Once you know that, you can identify these individuals predictably through behavioral and motivational questions that get to their core. Then you can recruit a group of truly like people to help with ideation or evaluation of product concepts and marketing messages.

It is far better to hear six individuals describe something individually than listen to a group of six in a room. When individuals describe the same problem or express the same need while you speak with them one on one—without influence from others in a room—you know that you’ve found a pattern. And when you can predict what a person is going to say, either by contextual cues or because of prior responses, you know that it’s a pattern that you can capitalize on.

I avoid the “warm body to fill a seat” approach that many firms use to recruit participants. Instead, I use recruiting techniques that focus on consumers’ behaviors, attitudes, and context. I use standard demographics such as income, age range, or gender to map to our client’s segmentation to satisfy the marketers in the room—and to prove to them that demographics just don’t matter. An ideal participant is someone who has “never participated in anything like this before.”

You Cannot Use Online Surveys to Conduct True Laddering

If focus groups are not the best approach to laddering, then online surveys certainly aren’t either. They present their own set of problems for conducting research overall. For instance, how do you know the right person is even taking the survey? How do you know the question is the right question? Even the best survey writer can craft a confusing or misinterpreted question, and the online survey environment doesn’t allow for follow-up. You should use this research technique only when you’re confirming what you already know. Never ever use it for exploratory research.

I have talked with many people who admit to flying through the survey to get the $5 at the end to use for shopping at their favorite merchant. These participants have no vested interest in providing thoughtful responses; they simply see it as a “time is money” proposition and often complete the surveys while engaging in other tasks. They know how to answer the questions to get into the database and participate in as many surveys as possible, and they’re much more interested in quantity than quality. Do you really want to base the future of your brand on the responses of someone who is willing to complete a 20-minute survey for $5?

If discussing this compensation in the context of demographics, does this even fit with what your demographic or segmentation studies tell you your consumers earn for the same amount of time?

I uncover further evidence against using online surveys in the laddering processes itself. You will learn while laddering your consumers that there are groups that will never participate in an online survey. And they may very well be a part of the consumer group that you need to reach most, maybe even your biggest opportunity. How can you continue to create products and services if you’re ignoring the most critical group’s primary avenue for sharing feedback and desires?

I can get these very people to participate in a conversation when I take the time to establish a relationship with them. In fact, relationship is what drives these groups and keeps them from participating in surveys. By taking the time to connect with these groups in the manner and environment they wish, I am able to hear all the voices, not just those willing to participate in anonymous surveys. I want and need to talk to these people to get a complete picture of what will and will not work when conducting a proper laddering study.

As we move even further into a relationship-based society, we have to consider the following: Why would consumers think you care if you are not willing to sit down with them in their environments and truly understand who they are and what they want? Compare this with the process of buying a present for someone for his or her birthday or a holiday. The best gifts always come from a true understanding of what’s important, dear, and core to the receiver. The consumer who is spending money with your company deserves and expects the same level of respect and understanding.

Start with What You Already Know

Understand that I am not proposing that you throw out everything you have ever done when undertaking a laddering project. You should most definitely use existing knowledge about your customer base as a starting point. You have been successful making sales to groups of people over a given period of time, so you know your approach is not completely wrong. It’s just not enough to survive long term or to make significant strides in product innovation and marketing strategy.

I go into every laddering project using the information a company can already tell me about its consumers. I use demographics, life stage, or other segmentation information that’s been derived from the company’s big data sources as a starting point or a hypothesis. I just don’t assume that this knowledge is important or the hypothesis is accurate to the consumer’s decision-making process until I hear the consumer tell me so or I understand it from the patterns I uncover in the consumer’s behavior.

Starting with existing knowledge allows you to begin to uncover what works or what doesn’t. It provides a common language, a bridge between existing knowledge about the consumer and what is learned during the laddering process.

In the next chapter, I will discuss the discrete steps you must take to properly perform laddering from the right perspective: that of your consumer, not your product, service, company, or brand.

- Thomas J. Reynolds and Jonathan Gutman introduced laddering based on Means-End Theory. Their approach states that product attributes lead to consequences that generate personal meaning (values) for users.

- When mass production was the common approach, brands performed laddering on their products to understand key features. The marketer started with the product and worked to understand how to make the consumer buy the product by appealing to a higher-order need such as fitting in or being seen as cool by others.

- To build products for your consumers today, you need to understand what they want. Only by understanding their core drivers can you become an architect of a product, service, or experience that will resonate with your end consumers.

- Consumers need a concrete idea or concept to react to, much like the architectural plans for a house. They will not be able to ideate for you, but they can react to what you show them.

- Focus groups and online surveys are not a proper shortcut to understanding your consumers. They do not allow you to get to the core of each individual who is participating in the research, and the very nature of the techniques introduce bias.

- Laddering doesn’t require you to begin completely from scratch. You can start with what you already know about consumers from the work you’ve already done with them. Just don’t analyze the results with these patterns until you confirm their validity with the actual source: the consumers themselves.

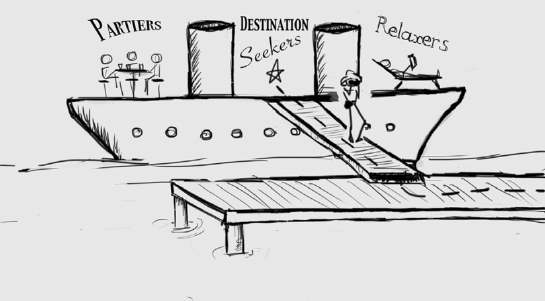

Figure 3.1 There Are Three Major Factors in Deciding to Take a Cruise Vacation: Destination, Party and Leisure