Chapter 4

Standard forms of professional appointment

This chapter:

- reviews in detail the RIBA Standard Professional Services Contract 2018

- contains hints and tips for negotiation with clients

- contains an overview of the main alternative standard forms of appointment.

4.1 RIBA Standard Professional Services Contract 2018

4.1.1 Form and content of the RIBA Standard Professional Services Contract 2018

The RIBA Standard Professional Services Contract 2018 (RIBA Standard PSC or PSC 2018) contains four elements: the Agreement (essentially the signing block); the Contract Details, setting out all the key commercial terms and project-specific information – site address, description of the brief, basis of the fee and so on; the Contract Conditions – the terms and conditions of appointment themselves; and the Schedule of Services.

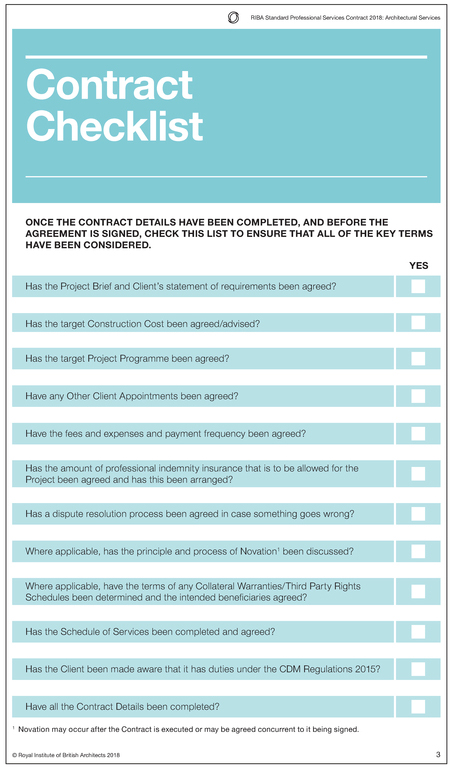

The RIBA Standard PSC also comes with an extremely helpful schedule of Guidance Notes, and a Contract Checklist setting out all of the details that need to be considered before the appointment can be agreed – for example, has the brief been agreed; and has the level of professional indemnity insurance been settled and the cover arranged? In this way an architect can check through the list to ensure that all of the key terms have been considered before the agreement is signed.

It is strongly recommended that a standard form, ideally the RIBA Standard PSC, is used by an architect as the basis for any appointment. However, commercial clients might not want to accept, in whole or in part, the RIBA Standard PSC. In contrast, there has in the past been almost universal acceptance of the RIBA Plan of Work Stages as setting out a generic outline plan of work for any project. The Schedule of Services contained in the RIBA Standard PSC follows the RIBA Stages. The RIBA Job Book (2013, RIBA Publishing) expands on and explains the services required of the architect to adequately complete each stage. A good rule of thumb is that if you are not using the standard RIBA Schedule of Services then the more specific you can be about the services you are providing, the better.

4.1.2 Client's responsibilities (Clause 2 RIBA Standard PSC)

Under the RIBA Standard PSC, the architect’s work is to an exten collaborative and the client cannot, by appointing an architect, excuse themselves from all responsibility for those areas of a project covered by the appointment. The client’s obligations set out in clause 2 are extensive, more so than many commercial clients would want.

Clauses 2.1.1, 2.1.2 and 2.1.3 in particular require the client to provide certain information, decisions and approvals in order for the architect to be able to perform the services effectively and meet any programme requirements. Under clause 2.1.1 it is for the client to advise the architect of the client’s brief, the construction cost, the timetable and the services

Figure 5 RIBA Standard Professional Services Contract 2018 Checklist

required, and any subsequent changes required. It is explicit that the architect is reliant on the input received from the client, and this may in practice be a useful way for an architect to defend themselves against a claim for negligent performance. Most clients would presumably wish to be able to rely on the architect’s input into these documents, or at least for the process of their creation to be more collaborative. This provision could also be read as a way of tying the client into a definitive approval of these elements, limiting the client’s scope to claim later that any input from the architect was negligent. This could provide significant protection for the architect.

Clauses 2.1.2 and 2.1.3 are also, as a client would see it, potentially onerous. Clause 2.1.2 requires the client to effectively assess what information (obtainable by it or in its possession) is necessary for the ‘proper and timely’ performance of the architect’s services – there is no scope for the client to rely on the architect’s expertise in requesting information that the architect considers relevant; the client has to make this judgment. Clause 2.1.3 obliges the client to give decisions and approvals necessary for the proper and timely performance of the services; what these decisions and approvals might be is not expressed, but the obligation could be widely drawn on the basis of the wording used.

Clauses 2.1.5 and 2.1.6 are effectively net contribution clauses relating to other consultants appointed by the client, and the contractor. The clauses oblige the client to hold such other consultants or the contractor (and not the architect) responsible respectively for their services and works in compliance with the relevant professional appointment or building contract. These are further useful limitations on the potential scope of the architect’s liability, as it may often be the case that there is an overlap in design responsibility between the architect and another professional consultant, or that both the contractor’s workmanship and the architect’s design could be the cause of the same problem. These clauses would seem to make it incumbent on the client to only claim against the architect for their part in any fault.

A significant danger for an architect appointed as contract administrator is the possibility of direct client dealings with the contractor. This can become a particular issue on some projects, for example domestic projects where the family continues to live in or visit the site regularly. In this case, the temptation to directly instruct additions or changes to the work carried out by the contractor can be hard to resist. Such interference can make it very difficult for the architect to carry out their contract administration role. Clause 2.1.7 makes clear that any such direct dealing by the client would constitute a breach of contract.

Clause 2.3.1 is another limitation on the scope of the architect’s liability, this time providing that the architect does not ‘warrant’ (here meaning an explicit commitment to achieve a particular outcome) the granting of planning permission, other third party approvals or their timing, Further, under clause 2.3.2 the architect does not warrant compliance with the client’s stated construction cost or timetable. For some clients, these concessions may be hard to accept.

Clause 2.3.3 limits the architect’s liability by providing that the client acknowledges the architect does not warrant the competence, performance, work, services or solvency of any other contractor or consultant appointed by the client. Although not expressed explicitly, the practical effect of this clause may be to limit the architect’s liability to their own defaults only – effectively a net contribution clause. Net contribution is dealt with below in the context of clause 7.3 (see section 4.1.7), but put simply a net contribution clause reverses the common law position of ‘joint and several’ liability. It would prevent a client from pursuing the architect for the whole of their losses in cases where one or more other parties are also arguably responsible.

4.1.3 Architect/Consultant's responsibilities (Clause 3 RIBA Standard PSC)

This clause sets out generally the obligations and authority (to use the phrase from the previous version of the RIBA standard appointment) of the architect. PSC 2018 uses the wording ‘Architect/Consultant throughout, as it is intended to be appropriate not only for use by those registered with the ARB under the Architects Act 1997, but also those design professionals who are not registered and are unable to describe themselves as ‘architects’.

In the absence of the contractual standard of care set out in clause 3.1, the architect’s fundamental duty would be to exercise reasonable skill and care in accordance with the normal standards of the architect’s profession. This standard of care is the one which would be implied at common law; the case of Bolam v Friern Hospital Management Committee established this as the standard. A term to the effect that the architect will carry out their services with reasonable skill and care is also implied, where the architect is supplying services in the course of their business, by Part 2, section 13 of the Supply of Goods and Services Act 1982, and by the Consumer Rights Act 2015 for contracts entered into after 1 October 2015.

An experienced client will often seek an enhanced standard of care referring to the architect’s specific expertise – there is a detailed discussion of this issue in section 5.2.6 – and clause 3.1 of PSC 2018 provides for this with a standard that is more onerous than that contained in previous RIBA standard forms. The standard is expressed as an obligation to exercise the reasonable skill, care and diligence to be expected from an architect ‘experienced in the provision of such services for projects of similar size, nature and complexity to the Project’. Even though this duty is more onerous than before, the architect’s liability is not absolute and, as discussed in section 2.3.4, if a loss is suffered by the client as a result of the acts or omissions of the architect, the architect will not necessarily be liable. It must be shown by the claimant that the architect’s performance fell below the required standard of care.

Clause 3.1 provides that, the standard of care applies both to the performance of the services and to all of the architect’s other duties and obligations under the agreement, and that nothing contained in the agreement shall be construed as imposing any greater duty of care.

4.1.4 Assignment, Sub-contracting, Other Client Appointments and Novation (Clause 4 RIBA Standard PSC)

Clause 4.1 prevents assignment of the benefit of the appointment by either party without the prior written consent of the other. This is important because unless there is something in a contract preventing or restricting assignment, the benefit is generally freely assignable. What is the benefit of the appointment? For the architect it is the right to payment of fees; for the client it is the right to receive the services contracted for. A commercial client will often want to have the ability to assign the benefit of the appointment, for example to a funder or another group company, and may be unwilling to accept that it must seek the architect’s written consent.

In an important concession to the commercial realities of high-value, complex projects involving third party funding, clause 4.4 of the Standard PSC 2018 contemplates the architect executing collateral warranties or granting third party rights. This may occur in the context of novation to a design and build contractor, where the original client will inevitably want a collateral warranty or the granting of third party rights from the architect in order to protect its ongoing interests. But interested third parties such as funders, or a purchaser or tenant of the project, may also want the benefit of a direct contractual relationship with the architect in order to protect their interests, and this option is provided by the wording of clause 4.4 and item (M) of the contract details to be completed by the parties.

The main issue for an architect is whether the job in question is sufficiently important for it to be appropriate to consider extending the scope of their contractual liability out to third parties. If it is, the form of collateral warranty or schedule of third party rights is key; an agreed form should be attached to the appointment to avoid the architect or client being asked to provide something different, and potentially more onerous, at a later stage. It is also important for the client to attach the desired form of collateral warranty, because a contractual obligation to provide a collateral warranty in a form ‘to be agreed’ is unlikely to be enforceable at all. It is not generally possible as a matter of contract law to enforce an agreement to agree something later. Collateral warranties and third party rights are discussed in detail in Chapter 6.

Clauses 4.5 to 4.8 inclusive set out a mechanism for the ‘burden’ (the obligations) under the appointment to be transferred. Legally, this is not as simple as an assignment of the benefit. The burden of a contract can be transferred to a third party, but only by agreement between the original parties and the incoming party accepting the burden. This is known as novation, which is discussed in more detail in Chapter 6.

4.1.5 Fees and expenses (Clause 5 RIBA Standard PSC)

The basic payment structure

Setting the correct fee for a project, be it a percentage of the construction cost, a resource-based lump sum, or on the basis of time charges (all of which are options under clause 5) is crucial for an architect, as is cash flow, governed by the timing of fee payments. The basic fee, calculated in accordance with clause 5.2, relates to the performance of the services; under any appointment there should always be scope for payment of additional sums for expenses and disbursements and, importantly, ‘additional’ services.

The RIBA PSC terms go further than this and allow for adjustment and additions to the basic fee in a number of circumstances. Clause 5.4.1 allows for adjustment, including the allowance of loss and expense, in the event of material changes to the brief, the construction cost or the timetable (unless such changes arise because of the architect’s breach of contract), or if the services are varied by agreement. Clause 5.5 allows additional fees if the architect does extra work or otherwise incurs loss and expense, for reasons beyond their reasonable control. Reasons given may include the architect being required to vary work, provide a new design or develop an approved design, or the performance of the services being delayed, disrupted or prolonged.

Clause 5.20 prevents the client from exercising rights it would generally have at common law to ‘set off’ sums against the fees claimed by the architect. Knowledgeable clients will be aware of the potential benefit of being able to say ‘I would be obliged to pay you, but because I have a counterclaim against you for defective or incomplete work I am entitled to hold onto a sum equivalent in value and set this off against your claim.’ Such clients will be reluctant to give up their rights to set off.

Clause 5.21 allows the architect to issue an account for payment for work carried out to date in the event of suspension or termination of performance under the appointment, even if as a result of the architect’s default. Again, a sophisticated commercial client might be unwilling to agree to payment in such circumstances until completion of the services. The client may consider that they are owed money in the final outcome if they have been put to the trouble of engaging a different architect to complete the services, and consequently their costs have gone up. Similarly, a commercial client might resist the principle of paying loss and damages resultant on the termination or suspension, in any circumstances, and is also likely to resist the principle of paying loss of profit.

Clause 5.22 is another useful tool for the architect, obliging any client who is late in making payment of a sum due under the appointment to pay interest on the outstanding sum at 8% per year above the Bank of England base rate at the time. This is the rate required by order under the Late Payment of Commercial Debts (Interest) Act 1998 (Interest Act 1998), but many commercial clients would try to reduce this rate while still complying with the Act – often to as low as 2% over base. Clients who are ‘consumers’ would not ordinarily be subject to the Interest Act. Special care is required if an architect wishes to include such a provision in their appointment with a non-business client.

Payment and pay less notices (Clauses 5.10 to 5.19 inclusive of RIBA Standard PSC)

These clauses set out the provisions on timing and withholding of payment necessary to comply with the 1996 Construction Act as amended by the 2009 Construction Act (the Construction Acts).

The process begins under clause 5.10 as payment becomes due to the architect on the date of issue of their account, which counts as the architect’s ‘payment notice’. So if you have done the work, issue your invoice. Clause 5.10 provides for the architect to issue payment notices (their invoices) at the intervals specified in item (I) of the contract details at the beginning of PSC 2018; this will typically provide for invoicing at least once every month, although there is the option to agree different intervals, for example based on the achievement of ‘milestones’ or as set out in a bespoke payment schedule. This is a judgment to be made on a project-by-project basis. It can be useful to break the fee up into particular percentages for each stage of work – this limits the scope for the client to dispute that a sum is payable. But in any case, submitting a monthly fee account, based on a schedule of fee instalments (included in the appointment, describing the percentage due at each fee stage) and a detailed record of work carried out, is a useful habit to get into.

Chase up any invoice persistently if it is not paid on time. The final date for payment of the sum due to the architect is 14 days from the date of issue of the account in question. The amount of the payment notice will be the ‘notified sum’ as described in the 2009 Construction Act.

Clause 5.16 sets out the mechanism, required by the Construction Acts, by which the client must give notices of the amount they will pay and the amount they propose to withhold, in response to the architect’s application for payment. Under clause 5.16, if the client intends to pay less than the notified sum they must give a written notice to the architect not later than 5 days before the final date for payment (which is 14 days after the date on which the architect issues their account), specifying the amount that the client considers to be due on the date the notice is served, the basis on which such sum is calculated, and if any sum is intended to be withheld, the ground for doing so or, if there is more than one ground, each ground and the amount attributable to it.

If no such notice of intention to pay less is given, the amount due to the architect shall be the amount stated as due in the architect’s account and the client shall not delay payment of any undisputed part of the architect’s account.

Failure to serve a withholding notice leaves the client liable to pay the full amount contained in the architect’s application by the final date for payment. If no notice of intention to pay less is served and payment is not made by the final date, the architect has a statutory right under the Construction Acts to suspend performance of the services on giving 7 days’ notice to the client; this right cannot be contracted out of, and is repeated in clause 5.11.2 and clause 9 of the RIBA PSC. Suspension is a powerful tool; many architects would, if faced with a continuing failure to pay, chase payment informally at first in order to preserve good relations with the client. However, the threat of suspension and the ability to serve a formal notice of intention to suspend performance are available from the moment the final date for payment is missed. Beyond suspension, the ultimate sanction would be to instigate the formal dispute resolution procedures under the appointment to recover the outstanding sums, either before or after exercising any contractual right to terminate the appointment. Consulting a solicitor before taking such measures is strongly recommended.

Bearing in mind the consequences for the client if they fail to comply with the pay less notice procedure, is it incumbent on the architect to explain how the mechanism works – to tell the client how to properly withhold the architect’s fees? The answer must be yes, although the degree of explanation required will depend on the nature of the client. As will be discussed in section 4.1.12, the architect has particular obligations in relation to clients who are in the position of a ‘consumer’, as defined by the Consumer Rights Act 2015.

4.1.6 Copyright licence (Clause 6 RIBA Standard PSC)

The common law position on copyright is restated in clause 6.1 – the architect owns the copyright in the original work produced in the performance of the services. This encompasses any designs and the drawings representing them; all other things being equal, the architect is free to reproduce their design on another project, and free to sue the client or anyone else if they attempt to do the same without permission. This is fair; an architect’s designs are a fundamental part of their business.

The client is granted, by clause 6.3, a licence to copy and use the drawings and other material produced by the architect, and the designs contained in them, for the purposes only of the project in question. Clause 11, relating to information formats, provides the client with a similar licence in relation to electronic drawings, data and documents. Use of the designs for any part of any extension of the project, or on any other project that the client might be involved in, is forbidden without the consent of the architect. In practice, such consent may be subject to the payment by the client of an additional fee.

Clause 6.3 links the copyright licence to the payment of all fees and other amounts properly due to the architect. If the client is in default, the architect may suspend further use of the licence on giving 7 days’ notice of their intention to suspend as set out in clause 6.7. This right to suspend the licence may be of limited value for the architect against a client who is habitually late in paying. In the event of a more fundamental breakdown in the client/architect relationship, however, it can help to concentrate the client’s mind if, as well as a claim for outstanding fees, there is also a claim for breach of copyright.

Clients, particularly commercial clients, regularly reject in principle the linking of the copyright licence with the ongoing payment of fees. Many clients are wary of the possibility of an injunction to prevent work continuing, reasoning that the potential liability for breach of copyright if the licence is suspended could lead to the project being held up each time there is a payment dispute with the architect. However, no court would grant an injunction to halt a project halfway through in response to a breach of copyright claim. An injunction is a remedy that is available to prevent a breach of copyright and is by definition only available before the breach has taken place. So what is really at stake is the potential for the architect to sue to recover the amount they should reasonably have been paid for the licence to use the copyrighted material – another monetary claim.

One client, presumably thinking about the prospect of an injunction bringing their project to a standstill, described the fee/licence link during negotiations as ‘being held to ransom’, which somewhat misses the point that the client can avoid any copyright licence issues, even under the RIBA wording, by paying the architect’s fees on time.

In what format should documents be provided? (Clause 6.4 RIBA Standard PSC)

When it comes to providing copies of the architect’s drawings and designs, clients regularly expect to receive the documents in an amendable format. However, clause 6.4 makes clear that although they may be produced in CAD, BIM or some other proprietary software, drawings and documents ‘shall be provided to the Client in PDF format only, unless an alternative format has been agreed and set out in item L of the Contract Details’. This reflects the position at common law; even under a bespoke professional appointment, unless the architect has expressly agreed something different, the client has no right to demand that the material to which the copyright licence relates is provided in the format which the client finds most useful. Architects should not feel compelled – unless they have agreed otherwise and been paid for doing so – to provide drawings in a format that would allow the designs to be amended and developed by other consultants.

From an architect’s perspective, there is an additional risk in its designs being developed by other consultants without the architect’s continuing involvement. It is not unreasonable for an architect to require that the client should pay a premium for this additional risk, if the architect is willing in principle to provide the documents in the client’s preferred format.

4.1.7 Architect/Consultant's liability (Clause 7 RIBA Standard PSC)

Time limit on actions (Clause 7.1 RIBA Standard PSC)

A time limit on actions in connection with the failure of the architect to ‘keep to the contract’ (presumably drafted in this way to allow the possibility of covering claims in negligence as well as breach of contract) is provided by clause 7.1. The limit is expressly dependent on how the appointment is executed, so will be 6 years for a simple contract or 12 years for a deed. Two alternatives are given for the date when the period starts to run, those being the date of the last service performed by the architect under the appointment, or the date of practical completion under the building contract for the project, whichever is earlier.

This clause may protect an architect against claims in negligence for latent defects, where you will recall from Chapter 2 that the limitation period can be longer than 12 years, but of course the appointment terms only bind the architect and the client, and would not prevent third parties from bringing claims in negligence (if they can overcome the legal difficulties involved in establishing the necessary duty of care) after the agreed period has expired.

Limit on liability to the level of insurance (Clause 7.2 RIBA Standard PSC)

Clause 7.2 contains an even more significant limitation on the architect’s liability. It provides that the architect’s liability for loss or damage shall not exceed the amount of the architect’s professional indemnity insurance (PII) required for the project, as set out by the parties in item (J) of the contract details. This may of course be an amount less than the architect’s actual total PII cover. This is an absolute cap on the architect’s potential liability for any individual claim by the client, and if it is agreed in the appointment the architect can be certain of the potential extent of their exposure in the event of a claim by the client.

Clients are not always receptive to such limits, reasoning that there is no such artificial limit on their own potential losses if something goes drastically wrong. However, there is something appealingly pragmatic about a claim-by-claim overall cap on liability set at the level of PI maintained by the architect. The cap provides certainty for the client as well as the architect. The client could not realistically hope to recover more from the architect than the level of their insurance anyway, without time-consuming and costly litigation to get at the assets of the firm clause 7.2.2 operates to prevent claims against individual employees or agents (directors or partners) within the architect firm, so there is no scope for the client to try and pursue such individuals for their houses or other possessions.

Although a sensible provision, clause 7.2.1 does not provide absolute protection for the architect. First, the architect must actually have maintained the level of PII agreed and included in the project data. Second, the clause refers simply to the level of PII, not to the amount which the architect may actually recover from their insurer in relation to any claim. If the insurance covers only part of a claim (for example because the amount claimed exceeds the headline level of PII cover), the architect is left to bear the shortfall from their own assets. Finally, the cap is only effective in relation to claims from the client, as only the client and the architect are ordinarily bound by the terms of their appointment. So if a claim is received from a third party in negligence or under a collateral warranty, and the PII pot has been used up, the architect will again be left with a gap in their cover. Third party claims might not be a particularly remote possibility on a large project. An architect may have been required to provide numerous collateral warranties in favour of purchasers, tenants and funders, who may all suffer a loss as a result of the same default. A single ‘claim’ as defined by the architect’s PII policy may include any individual action resulting from the same negligent cause – in such circumstances the single limit of indemnity could be exhausted very quickly.

Net contribution (Clause 7.3 RIBA Standard PSC)

Clause 7.3 contains a potentially controversial limitation on liability. The clause provides that the architect’s liability shall not exceed such sum as would be apportioned to the architect by a court if the architect paid only up to the extent of their share of the fault. The calculation of what share of the fault would be apportioned to the architect is based on the assumption that all other consultants and contractors providing work and services for the project have paid to the client their fair share of the client’s losses, along with the assumptions that all those parties owe similar contractual undertakings to the client and there are no limitations or exclusions of liability or joint insurance provisions between any of those parties and the client.

In other words, in the event of a claim, thanks to clause 7.3, the architect can only ever be liable for their fair share of the losses incurred.

A net contribution clause like this reverses the common law presumption of joint and several liability. If the client suffers a loss as a result of a default caused by more than one party, they are ordinarily entitled to sue any one of those parties to recover the whole of their loss. The unfortunate culpable party is then left to seek contributions from anyone else who may arguably have been responsible for the client’s loss; a cause of action is available to the culpable party, who has had to bear the brunt of the client’s claim, under the Civil Liability (Contribution) Act 1978 (the 1978 Contribution Act).

The principle of joint and several liability is very useful for clients, and sophisticated clients who are aware of the advantage that the common law position gives them will often be very reluctant to give it up. In situations where more than one party is arguably liable for their loss, the client can simply sue the culpable party with the deepest pockets and avoid expensive multiparty litigation (adjudication, the quickest and most cost-effective form of adversarial dispute resolution, is not suitable for pursuing multiple parties), and the expense of obtaining expert evidence to prove which party was liable for which part of the loss. Joint and several liability also means that the client does not bear the risk of one of the culpable parties becoming insolvent. If the contractor and the architect are both partly responsible for the loss, and the contractor has become insolvent, the client is free to recover 100% of their losses from the architect. After the contractor’s insolvency, the architect in this example may have no other avenues for recovering contributions towards the damages they have had to pay. If the architect had included a net contribution clause in their appointment, it would be for the client to bear the insolvency risk.

Is it reasonable for an architect to have a net contribution clause in their appointment?

The common law position may seem counterintuitive. How can it be right for an architect to foot the bill for losses that were caused by other parties; for the law to allow an architect to be 100% liable for the damages, even though their share of the blame might be 10% or lower? But many clients will take a different view. The project, and hence the work for the architect, would not exist without them. Why should the client bear the risk in the culpable parties becoming insolvent, and the risk of paying potentially huge legal costs to sue multiple parties, when the client has done nothing wrong? Clients are particularly wary of including design and build contractors in the net contribution equation; if the contractor is responsible for the whole of the design and build of a project, what is the architect’s fair and reasonable share of any loss? Arguably, nothing at all.

The balance of power between commercial clients and architects is such that it remains unusual for a net contribution clause to be agreed in a professional appointment, although clients are often more relaxed about agreeing net contribution in collateral warranties, particularly for tenants and purchasers, if not for funders. Failure to obtain a net contribution clause in a professional appointment leaves the architect facing a number of risks. Their ability to obtain contributions from other culpable parties can be undermined by various factors, including the insolvency problem outlined above. Under the 1978 Contribution Act, the party from whom a contribution is sought (in our example, by the architect) must be liable to the client for the same loss or damage as the architect. This may not be the case if, for example, there is no contract between the client and that other party; or if the other party has a contract with the client, but liability for the loss or damage in question is excluded under the terms of the contract.

4.1.8 Professional liability insurance (Clause 8 RIBA Standard PSC)

Clause 8.1 sets out the architect’s obligation to maintain a PII policy. It is extremely important that the obligation mirrors precisely the key terms of cover of the policy the architect actually maintains, and the headline level of cover must be no greater than the level of cover actually maintained.

The architect can include appropriate wording in item (J) of the contract details to ensure that the obligation matches the reality, not just in terms of the headline level of cover, but also any aggregate or reduced aggregate limits, or even exclusions, their policy may contain. Aggregate limits and exclusions often apply to claims in relation to pollution, contamination or asbestos.

The obligation to maintain PII is subject to such insurance being available to the architect on commercially reasonable terms; so, in the RIBA PSC at least, this is not an absolute obligation. The ARB’s Architects Code is more strict; Standard 8 of the code requires that architects have ‘adequate and appropriate professional indemnity insurance cover’, adequate to meet a claim whenever it may be made.

The wording of clause 8.1 is nevertheless advantageous for the architect. Because the obligation is subject to insurance being available to the architect on commercially reasonable terms it does not matter whether other architects might be able to obtain such cover. In this way, the RIBA PSC allows the architect’s own claims record, which may be the reason why they cannot obtain insurance at a reasonable premium, to be used as a reason for not maintaining insurance. How much of an issue this is in practice is questionable – no sensible client would engage an uninsured architect, and no sensible architect would continue to practise without PII cover, high premium or not. Some clients do not like this subjectivity, and will insist on an insurance obligation that allows derogation only if such insurance is not available to the market generally on commercially reasonable terms. It can be hard to argue against this, although an architect might justifiably say that the position of the market in general is irrelevant; if PII is not available to me, personally, I cannot enter into an obligation to obtain it.

4.1.9 Suspension or termination (Clause 9 RIBA Standard PSC)

Not every client is happy to give an express right for the architect to terminate their appointment, even for material breaches of contract by the client. The market norm seems to be that both the architect and the client have the right to terminate the appointment, but these rights are asymmetrical; the circumstances in which the architect may exercise their right to terminate are more restricted than those in which the client may terminate. This is not reflected in clause 9 of the RIBA PSC. Commercial clients may often want the right to terminate the architect’s appointment on notice, without any fault on the part of the architect. This may seem unfair, but if funding for the project falls through, or the project is no longer wanted, it would be unreasonable to tie the client in to an appointment with an architect to provide services that the client cannot afford or does not want. The flipside of this is that most commercial clients would be unwilling to accept an appointment that would allow the architect to simply walk away from the project on notice without any fault on the part of the client. Finding a replacement could be costly and the process could delay the project. Clauses 9.1 and 9.2 gives the parties rights to terminate the appointment on notice, stating the reasons for doing so. Although the architect’s rights as set out in clause 9.2 appear to require breach or default on the part of the client as a ground for termination, the wording is ambiguous, and arguably an architect could give notice to terminate on the grounds that it had won a more profitable job elsewhere; it seems unlikely that commercial clients would accept such ambiguity.

Clause 9.2 enhances the architect’s statutory right to suspend performance for non-payment of fees, conferred by the Construction Acts. Clause 9.2.3 allows the architect to suspend performance if prevented from or impeded in performing the services for reasons beyond their reasonable control or (clause 9.2.5) a ‘force majeure’ event. Force majeure means literally ‘greater force’, implying the intervention of some higher power, and is typically understood to include events such as flood, earthquake or volcanic eruption. Such clauses, especially clause 9.2.3, are again generally not popular with commercial clients. An event that to an architect is ‘beyond its control’ may look to a client more like a failure to anticipate an event that was reasonably foreseeable.

4.1.10 Dispute resolution (Clause 10 RIBA Standard PSC)

A number of procedures are contemplated by this clause. It is for the parties to set out in item (K) of the contract details whether they agree to mediation as an option and whether arbitration or litigation apply Adjudication is noted as an option, but not a default option; architects should bear in mind that statutory adjudication under the Construction Acts is not generally available in a dispute with a residential occupier Although the parties are free to expressly agree to its application in their contract, architects will need to explain the disadvantages of adjudication to consumer clients.

4.1.11 Consumer clients and the RIBA Standard PSC 2018

PSC Standard 2018 makes no concessions to the position of ‘consumer’ clients. A consumer is defined by the Consumer Rights Act 2015 section 2(3) as an individual (not a company, partnership, club or society) who, in making a contract, is acting for purposes that are wholly or mainly outside that individual’s trade, business, craft or profession. PSC 2018, in its Guidance Notes, states explicitly that it is not a suitable agreement for non-commercial work undertaken for a consumer client, ‘such as work done to the client’s home, including renovations, extensions, maintenance and new buildings’. The old RIBA standard form clause 10, which provided protection for consumers by allowing them to cancel the appointment on notice for any reason within 7 days starting from the date when the contract was made, has been removed.

4.1.12 The RIBA Domestic Professional Services Contract 2018

The RIBA produces a separate Domestic Professional Services Contract 2018 (Domestic PSC). The Guidance Notes to this form expressly state that the Domestic PSC has been devised as an agreement between an architect and a consumer client relating to work on the client’s own home, and the terms include a right to cancel in similar terms to the wording that formerly appeared in the main RIBA standard form of appointment.

Architects must exercise particular caution when entering into an appointment with a consumer client. There is a risk that certain terms of the RIBA Standard PSC suite, even the Domestic PSC, will be invalidated and ineffective against a consumer client if the architect has proposed the form of agreement and its terms have not been individually negotiated. The same risk applies equally to any other standard terms and conditions of agreement, including industry standard forms such as the International Federation of Consulting Engineers (FIDIC) and NEC4 appointments, as well as any architect’s own ‘standard’ terms and conditions. According to the Consumer Rights Act 2015 (CRA 2015), ‘an unfair term of a consumer contract is not binding on the consumer’ and a contractual term will not be upheld by a court against a consumer if it is unfair.

Section 62(4) of the CRA 2015 provides that a term is unfair ‘if, contrary to the requirement of good faith, it causes significant imbalance in the parties’ rights and obligations under the contract to the detriment of the consumer’. Good faith in this context means simply that the parties making the contract should not deceive each other. Fairness is determined by reference to the nature and subject matter of the contract, as well as by reference to all the circumstances existing when the terms was agreed.

Under the old Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations 1999 which used to apply in such circumstances, there was no ambiguity – a term was unfair which caused a significant imbalance of risk to the consumer’s detriment, and had not been ‘individually negotiated’. A term would always be regarded as not having been individually negotiated where it was drafted in advance of agreement and the consumer was as a result unable to exert any influence over its substance.

Ideally with a consumer client the architect should go through each potentially onerous term in turn in the context of the consumer’s rights and record in writing that this explanation process has taken place The Guidance Notes to the Domestic PSC do briefly provide advice on negotiating terms with consumers. Provisions relating to payment and payment notices, limitation of liability, professional indemnity insurance and dispute resolution may all ‘need careful explanation’, if the architect wishes subsequently to be able to rely on them. An architect is not necessarily going to be able to discharge their duty to explain terms to a consumer client by simply providing the Guidance Notes for the client to read without giving any further input.

If you know that a consumer client has taken no legal advice and you propose terms of appointment that contain significant limitations on your liability, such as the RIBA Domestic PSC 2018, without explaining to the client how these terms may prevent them from recovering the full extent of their losses in the event of a claim, then you are perceived in law to be taking an unfair advantage.

The risk of behaving in this way is that you would not in practice be allowed to rely on such limitations on your liability. This is a genuine risk, as the RIBA Guidance Notes suggest; it is surprising how often consumer clients maintain in the event of a claim that the full implications of a contractual provision were not explained to them, to their disadvantage.

The CRA 2015 helpfully, in its Schedule 2 (Part 1) provides an indicative (but not exhaustive) list of the types of term that may be considered unfair. They are not automatically unfair – it is for the consumer to prove that the application of a particular term is unfair – but an architect should be wary of proceeding to enter into the RIBA Domestic PSC with a consumer client without explaining the full implications of the following clauses in particular:

- the contractual embodiment of statutory provisions that would not ordinarily apply to consumers: clauses 5.10–5.24 inclusive (payment mechanics including payment and pay less notices under the 2009 Construction Act), 5.22 (charging interest under the 1998 Late Payment of Commercial Debts (Interest) Act), 5.11 and 9.2.1 (suspension under the 1996 and 2009 Construction Acts), and clause 10 (dispute resolution options – generally a consumer has a right to refer any dispute to the courts and need not be concerned with adjudication)

- provisions limiting sums that may be recovered: clause 7.2 (cap on liability)

- provisions potentially increasing costs liability, such as clause 5.20

- exclusions of liability: clause 7.1 (limit on actions in time) and clause 7.3 (net contribution).

Unless a project is unusually large or complex, it would be sensible for any architect taking on a project for a consumer client to consider using the RIBA Domestic PSC 2018 as the basis for its appointment.

4.1.13 Will my client agree to use the RIBA Standard PSC 2018?

Inexperienced domestic consumer clients will often be happy to use an RIBA standard form without amendments, such as the RIBA Domestic PSC. Very many projects every year use an RIBA standard form; not every project involves a major international developer and funders investing millions of pounds. The RIBA 2018 PSC suite of contracts may have evolved but the forms have the benefit of familiarity and, if not always drafted in language a layperson can easily understand, they are comprehensive, come with helpful notes and have the right ‘feel’ for many clients; it often just seems appropriate to use an RIBA document. Clients of this nature tend to be wary of the time and legal costs that are likely to result from trying to negotiate something bespoke, but they know they should get something formal in place. If the architect has something like the RIBA Standard PSC that they can propose to get the ball rolling, all the better.

Commercial clients may agree to use the RIBA Standard PSC, but it is likely to remain unusual for a commercial client, with the benefit of legal advice, to agree to use an unamended standard form, RIBA or otherwise, unless they are particularly hassle-averse. Like domestic clients, some commercial clients may be swayed by the convenience of agreeing the RIBA Standard PSC if the client either does not have its own bespoke form of appointment or does not want to pay a lawyer to draft one. They may in addition be unwilling to spend legal fees negotiating amendments, or may be unhappy with the possible increased fee an architect might seek in order to cover the additional risk of signing up to a bespoke appointment. The RIBA Standard PSC also has the advantage of being, and being known to be, insurable by architects’ PII providers.

Sometimes an architect could begin work with a limited scope and fee on the basis of an RIBA standard form; the work may later expand, but the issue of a new appointment to fit the additional risks to the client may never be addressed. If an architect has the opportunity to take the initiative and propose a form of appointment, the RIBA PSC suite is a safe option.

4.2 NEC4 Professional Services Contract

This standard form of consultant’s appointment is being used more and more, and increasingly on high-profile projects. As well as being the preferred form of appointment used by the Olympic Delivery Authority for work in relation to the 2012 Games, NEC forms have been widely used by influential clients in the Middle East, and by major clients in the utilities, energy, transport and education sectors in this country. Its popularity with major clients may be the result of its inherent flexibility; in a sense, the NEC4 Professional Services Contract (NEC4) is not really an industry standard form at all.

NEC4 consists of a number of core clauses, which are read in conjunction with selected ‘optional’ clauses, ready drafted, to cater for issues such as the provision of collateral warranties and an overall limitation on the consultant’s liability. Inherent in this scheme is that the client and the consultant may also agree to include additional conditions of contract – ‘Z clauses’ – which are bespoke, generally client-led, amendments to the standard clauses. This entails more than simply completing the project-specific contract data, as in the RIBA Standard PSC, as these bespoke additional terms and conditions may alter the balance of liability under the appointment. NEC4 is unique as a standard form in the way it, if not encourages, realistically accepts that clients will wish to use additional bespoke clauses to shift the burden of liability under the appointment further towards the consultant.

At its heart, NEC4 contains a duty to use the ‘skill and care normally used by professionals’ providing similar services. However, PII policies normally cover only ‘reasonable’ skill and care. This is just one example of a core clause within NEC4 that appears unnecessarily onerous or, if it is meant to mean ‘reasonable skill and care’, unclear. In any case, none of the major clients who use NEC4 do so without incorporating a schedule of bespoke Z clauses. For this reason, detailed analysis of the standard core and optional clauses is somewhat redundant. An architect is unlikely to be presented with the plain NEC4 as a proposed basis for an appointment; the real interest will usually be in the Z clauses, and they may significantly change the picture.

Also at its heart, NEC4 is really a sophisticated project management tool. It requires a sophisticated and experienced client to get the best out of it, and an experienced consultant to manage their side of the bargain. A party can suffer if they are not used to keeping the paper trail going. For example, core clause 61.3 imposes a condition precedent such that if the consultant wants to claim for additional fees or time as a result of a ‘compensation event’ (one of a list of possible events beyond the consultant’s control, such as the client giving an instruction changing the scope), then it has to notify the client that it wishes to make a claim within 8 weeks of becoming aware of the event. Without notification before the deadline, there is no entitlement.

Architects presented with NEC4 should proceed with caution and take legal advice, irrespective of whether the proposed appointment contains a significant number of Z clauses. There is much that an architect could find objectionable, in addition to the basic failure to subject the duty of skill and care to the usual reasonableness standard.

4.3 FIDIC Client/Consultant Model Services Agreement, Fifth Edition 2017

The International Federation of Consulting Engineers (FIDIC) professional services agreement is widely used on international projects in Europe, the Middle East and Asia. The basic duty of care required by the FIDIC standard form is reasonable and insurable, being simply ‘the reasonable skill, care and diligence to be expected from a consultant experienced in the provision of such services for projects of similar size, nature and complexity’. The wording of clause 3.3.1 makes clear that the consultant shall have no other responsibility than to exercise such skill and care whether in relation to its services or any of its other obligations under the appointment.

The consultant also has the benefit of an overall limit on its liability (clause 8.3.1), a limit on recoverable losses to those which were the direct result of a consultant breach (clause 8.1.3(a)) and a net contribution clause (clause 8.1.3(c)).

This sounds good in theory, but the FIDIC form is almost never used for consultant appointments on UK-based projects. Where it is used, primarily in the Middle East, it is rarely used unamended and is almost always subject to the law of a foreign jurisdiction required by the client.

Chapter summary

- The RIBA produces a suite of standard form professional appointment documents to suit different project requirements, including the RIBA Standard PSC 2018, the RIBA Concise PSC 2018 and the RIBA Domestic PSC 2018.

- PSC 2018 imposes certain obligations on the client and provides for significant limitations on the liability of the architect.

- The balance of risk in industry standard form appointments such as PSC 2018 is perceived by some clients as overly favourable to the architect.

- Alternative standard forms of professional appointment which an architect may be asked to agree include NEC4 and the FIDIC Fifth Edition.

- When contracting on the basis of an industry standard form such as PSC 2018, the architect needs to be able to explain the meaning and effect of the terms to the client as they may reasonably require.