8

Rapid Prototyping

Ability to create quick early versions of innovations, with the expectation that later success will require early failures.

When we change the way we communicate, we change society.

CLAY SHIRKY

IN ORDER TO MAKE THE FUTURE, you have to prototype it first. The resources for rapid prototyping will be magnified and amplified incredibly over the next decade, as Clay Shirky’s work points out convincingly:

This linking together in turn lets us tap our cognitive surplus, the trillion hours a year of free time the educated population of the planet has to spend doing things they care about. In the 20th century, the bulk of that time was spent watching television, but our cognitive surplus is so enormous that diverting even a tiny fraction of time from consumption to participation can create enormous positive effects.1

Prototyping is not new, but the art of rapid prototyping will be changed in profound ways by cloud-served supercomputing.

When I took my first computer programming class in 1970 at Northwestern, the professor noted that the two best programmers he had ever seen had extremely different strategies. One great programmer would carefully write out and mentally test his program before submitting it. (These were the days of batch processing where you brought your card deck to a large central computer.) The other great programmer would do a quick and dirty version and submit it right away to get the diagnosis of what did not work. The latter approach, I have now come to appreciate, was an early version of what we now call rapid prototyping.

Rapid prototyping enables us to learn from failure quickly, again and again. It is the trial-and-error method that has always been important for innovators, but on a faster cycle. The motto of rapid prototyping is to fail early, fail often, and fail cheaply as you make a better future.

Rapid prototyping is a perfect leadership strategy for the VUCA World—where truth emerges from engagement, trial, and error—because it allows leaders to try out their own ideas quickly, as well as tap into the maker instincts of a wide array of potential collaborators.

Few leaders get it right the first time, and it will get even harder in the future. Early failure will be key to later success. The failures of “computer conferencing” in the 1970s contributed to the eventual success of social media, for example. This lesson from failure took a very long time, however. In the future, leaders need to speed up the process. They should expect to go through multiple iterations of everything. As Alan Kay was known for saying when he was at Xerox PARC, “The purpose of research is to fail, but to fail in an interesting way.” Rapid prototyping is all about failing cheaply, in interesting ways.

Rapid Prototyping Defined

Rapid prototyping is quick cycles of try, learn, and try again—in an ongoing sequence. Making sense in the VUCA World requires immersion in that world with a learn-as-you-go style. Prototypes typically have lifetimes measured in hours or days, not months. They are different from pilot or demonstration projects, which often take much longer to conduct.

Rapid prototyping is the Maker Instinct applied to innovation. While the concept of do-it-yourself will still be important, the next generation of innovation will be driven by “do-it-ourselves” leaders who don’t get stuck on the idea of ownership since in this process people’s ideas get mixed quickly and it is often impossible to sort out who thought of what.

Leaders can learn from people’s pains, and innovation can help to relieve those pains. In rapid prototyping, the emphasis is not on abstract thought about possibilities or plans; it begins with real people, with the end users out in the field, and as early as possible in the innovation cycle. It begins with listening.

Companies can learn a lot from watching what people do with their products. Users are a remarkable source of new ideas for improving upon and reinventing products and services. The people who actually use a product can be a source of insight if companies are willing to learn along with them. Manufacturers create products, but no longer own them once they are purchased. The users may change them or use products in new ways. The innovation cycle is not necessarily over when the product is sold. The innovation cycle can keep going if the users continue to improve and the manufacturers learn along with them.

Leadership through rapid prototyping

• Is characterized by a trial-and-error mentality with an interest in starting quickly and learning continuously

• Emphasizes experience in the field, rather than advance planning

• Puts priority on extreme speed in learning

Traditional leadership has put a premium on thinking things through before acting. With rapid prototyping, leaders must expect to fail early in the process so they can succeed later.

In military conflicts, as I understand it, the rule of thumb is typically “one third, two thirds,” where one third of the time is spent planning a mission, and the other two thirds is used for preparation in the field. It is tempting, even in battle, to spend more time planning and less time preparing. Rapid prototyping goes the other way: leaders should minimize planning, but maximize preparing in low-risk settings and learning in the field. The rule of thumb for rapid prototyping is less planning, more learn-as-you-go action. Of course, going into battle when your life depends on it may require more advance thought.

At IFTF, our former president Roy Amara often employed what he called the “jump to the end” strategy as we began a new project. For a six-month project, for example, Roy would say something like: “Let’s do the entire project in a day. Then, we’ll come back and fill in the holes and decide what to do next.” It was an outrageous suggestion: do a six-month project in a day. But when we tried, we learned things about the project that we never could have imagined until we dove in. Rapid prototyping is learning by doing, but it is also doing by learning. It is a messy process, but it is also invigorating. The holes in logic become immediately apparent when you try to jump to the end.

Often the best way to do rapid prototyping is through the use of simulation or gaming to create realistic but low-risk learning environments. Rapid prototyping fits very well with the future leadership skill called immersive learning ability, which was described in Chapter 4. Leaders with immersive learning ability will find it much easier to do rapid prototyping. When faced with a new challenge, they could game out their possible responses before deciding what to do.

When I played basketball at the University of Illinois, we prepared for the next week’s game by creating a “scout team” in practice. The scout team’s job would be to simulate our opponents and run their plays. Scout team members would model their play on specific players from the other team. Our team would scrimmage against the scout team as a way of preparing our strategies and tactics of attack for the game—true rapid prototyping in action. Great practice teams usually do well during games because they have already prototyped and practiced in a realistic situation. Teams that spend too much time in the locker room planning and not enough time out on the court are at a disadvantage. The real learning happens on the court as the starting five prototypes ways of succeeding against the scout team. If the scout team does a great job, the starting five is more ready for the real game. You could also view this as a form of immersive learning, which links closely to rapid prototpying.

Dilemmas in the Future

Rapid prototyping is the first step in making the future. When I began my career in the early 1970s, much of the leading-edge innovation conducted at universities was funded by ARPA (Advanced Research Projects Agency, the research arm of the Department of Defense). The best ideas started with the military and gradually spread to consumer goods. Innovation tended to be top-down, driven and guided by central government policy. Leadership tended to be centralized and hierarchical. Now, just forty or so years later, it’s become much more decentralized. Innovation tends to happen bottom-up, fueled by consumer electronics, gaming, and the maker instincts of many. Now, the best ideas start in gaming and gradually spread back to the military and government.

Leaders have to learn how to fail, and then try again—all with an expectation of much iteration. Of course, simulations and immersive environments can help leaders try and fail in low-risk ways, but try and fail we must—in order to ultimately succeed in the VUCA World.

Rapid prototyping allows us to scale up and find solutions to international dilemmas. Scholars, designers, and decision makers around the world grapple daily with the dilemma of providing clean and safe drinking water to one of every six people on this planet. A research team led by Ernest “Chip” R. Blatchley III at Purdue University has been designing and prototyping solutions for twenty years.2 The team’s most recent breakthrough is an inexpensive system that renders waterborne pathogens inactive through the creative use of the sun’s ultraviolet rays. Blatchley’s team successfully tested the product as part of Purdue’s Global Engineering Program, with about two thousand systems currently in use in Kenya. The only way to succeed is to prototype your way to success.

PROTOTYPING IN DIASPORAS

Rapid prototyping works well within a diaspora because ideas spread more rapidly across a community of shared values and trusted relationships. News of the performance of a new beauty product, for example, will spread much more quickly among diaspora members who find the product beneficial. Testing a new idea is easier within a diaspora because it will circulate at a faster rate and reach a greater number of people—all in the same circle of trust. Diasporas are innovation breeding grounds if the innovations are a good fit with their values, priorities, financial resources, and availability of time.

Within a diaspora, rapid prototyping can begin with a small number of people but swiftly spread to many more. A diaspora is an army of potential prototypers—if the match is right. Active diasporas often make aggressive use of networked media. Offshore Chinese or Indian people, for example, are separated geographically from their homeland, but once they are joined electronically, word spreads in a flash.

PROTOTYPING CAN BE DANGEROUS

Innovation in the world of finance can be dangerous to everyone’s health. The mortgage crisis of 2008, for example, was fueled by financial innovation gone amok. Personal home mortgages were intended as long-term financial agreements between a homebuyer and a bank giving the loan. As financial “innovation” accelerated, however, these long-term two-party agreements were packaged and sold to others, creating a growing chain of debt instruments that could be traded on a short-term basis. When the system started to break down, it was hard to know where to turn, since the original long-term instruments had been packaged and repackaged for market trading that benefitted only the traders along the way until things fell apart. To fuel the system, people were encouraged to buy homes they could not afford. The home mortgage market started to look a lot like gambling. The Wall Street culture has gotten very good at attracting people who are very good at creating and playing zero sum games where in order to win, someone has to lose. These complex mortgage instruments were certainly creative and innovative attempts to game the system, but they created many more losers than winners.

In public settings, it is tempting to borrow ahead rather than pay taxes today—even though the costs to future generations will be high. The current taboo on tax increases makes it more likely that financial “innovation” will grow to help improve infrastructure without revenue generation that is perceived as increasing taxes. The danger is that such innovation will hide new risk, just as it did with the mortgage crisis.

Rapid prototyping could help financial institutions, but caution is appropriate because the risks are so high. Often, prototyping in the world of finance happens in the market, where the definition of what works is who makes money. I am not a financial expert, but my instinct is that rapid prototyping logic may not apply to the financial sector in the way it does in other parts of the economy. I also have my doubts about its value in public policy making.

In the United States, compelling anecdotes often drive policy making. When a bridge collapses, there is a great public outcry and an immediate discussion of who is to blame and what can be done to prevent further collapses in the future. Unfortunately, however, it is very difficult to sustain the sense of urgency long enough to pass legislation to support the rebuilding and upkeep for infrastructure—until the next disaster happens. When demands increase but taxes don’t, something else must be done to finance new infrastructure, and that something is not likely to play out well in the long run. The idea of rapid prototyping will often work better in business or research than in public policy. Public scrutiny and fear of failure sometimes discourage the practice of rapid prototyping.

Pilot and demonstration projects are often very useful to explore new policy ideas; rapid prototyping, however, moves much more quickly. New policies will be worked out in the field and rapid prototyping will be an important way to test out new ideas.

OPEN-SOURCE WARFARE

Terrorist groups, unfortunately, really get the concept of rapid prototyping. Insurgent warfare is focused on surprise and soft targets. Insurgent warriors try lots of tactics, and if one works, the new tactic spreads rapidly. If the terrorist group is a diaspora, the prototype results circulate even faster.

In the world of open-source asymmetrical warfare, the tactics will come from everywhere. Weapons will not just be traditional military-designed tools of war. Consumer electronics, games, and cell phones are the current weapon platforms of choice for many insurgent groups. In future warfare, rapid prototyping will be common terrorist strategy—which means that citizens and peacekeeping forces will need readiness training to prepare for surprise from many different directions.

Branches of the U.S. military and many other public service agencies, including police and fire departments, use a formal method called “After Action Reviews” (AARs) as a discipline for learning from everyday experiences.3 AARs fit very well with rapid prototyping, since they focus on learning from failures. Unlike performance reviews, AARs are focused only on what can be learned and what can be improved. AARs explicitly avoid the subject of blame. The army does keep a central database of lessons from AARs over the years, but the real value of AARs is not the database but the discipline.

As best I can tell, many army personnel participate in several AARs every day, one for every significant experience, it seems; or there is at least informal learning that takes place. AARs can be used very effectively as the feedback loop in the rapid prototyping process. Indeed, this discipline fits in well with learning from the early failures and applying those lessons to achieve later success. In the world of warfare, AARs mean that the lessons from insurgent attacks can be quickly learned and reapplied in the field.

AAR discipline works well in the military, police, and fire services, but I’ve never seen a private corporation practice it broadly—other than a few successful pockets. Why? Most corporations are not able to separate learning from evaluation. They may have policies stating that it is important to learn from failures, but in reality employees know that if they fall short they will be punished. Failure is accepted in theory, but in practice it is almost universally unrecognized. The only exceptions I’ve seen are Silicon Valley companies, where failure is often seen as a badge of courage. If you haven’t failed in Silicon Valley, it means you haven’t taken enough risks. The AAR approach, however, would be too structured for many Silicon Valley companies.

ORGANIZATIONS DESIGNED FOR PROTOTYPING

Some organizations within large corporations are now designed to do rapid prototyping. P&G FutureWorks (futureworks.pg.com), for example, is a corporate group focused on potential new products and service innovations that P&G might consider beyond its current categories. The leader of this group, Nathan Estruth, comes from a background in political science and political campaigns. By nature, Nathan is an organizer with a keen interest in new ideas, working in the context of a very large corporation. FutureWorks makes the future.

Rapid prototyping is basic to FutureWorks. I remember in the early days of their work (when P&G was still active in food), they were deciding whether or not to go into the energy bar market. At that point, they wanted to learn as much as they could about energy bars. The idea was to try out lots of options, and they fully expected to fail “early, often, and cheaply,” as was a motto in those days. They set up a room in their very flexible space that was dedicated to energy bars. Since I use them myself when I travel, I was very interested. When I went into the room, I saw more energy bars than I knew were in existence. Everyone on the FutureWorks team was using energy bars as part of their lifestyle, just to try out the concept. In parallel, they created a series of prototype energy bars that they tried out themselves, while also testing them with a variety of their target end users.

The first step in rapid prototyping is immersion in the world of end users with the aim of understanding their pains and their hopes. The second step is to begin prototyping. P&G FutureWorks decided not to pursue energy bars because it was impossible to isolate the benefits of the bar from the behavior of the person. The best of the bars contributed to weight loss, but only if the consumer developed an exercise program as well. Getting people to exercise is a lot harder than getting them to eat a tasty healthy bar.

Rapid prototyping should begin and stay as close as possible to the end consumers. For example (and this is an extreme example), when Nathan Estruth and his team created a new gravy dog food for the Iams brand, they literally ate dog food themselves as they developed the prototypes—as well as feeding the new food to dogs. In this case, prototypers really did eat their own dog food.

Rapid prototyping requires leaders to amplify their teams as much as possible—to immerse themselves in the future worlds they are trying to create. The best way to learn about these potential innovations is to try them out among the potential end users.

VISUAL PROTOTYPING

Rapid prototyping will benefit greatly from the tremendous improvements in our tools for visualization that will happen over the next decade. Visualization is a form of rapid prototyping in your mind and in virtual space. Pioneering work in this field is being done by The Grove Consultants International, founded by organization consultant and information designer David Sibbet.4 This organization teaches people to use visualization to imagine future possibilities and bring them to life. The Grove provides leaders with a method to rapidly prototype their own thinking and evolve their own stories about how things work in their world—similar to the way a design firm would prototype a new product. Conceptual prototyping can be just as effective as product prototyping, for many of the same reasons. Along the way, The Grove has developed graphic templates that help people imagine new strategies and make them practical.

Stimulated by new visual tools, leaders will be able to improve their visual literacy—the ability to understand and communicate in pictures, drawings, and other forms of imagery. Visualization, like other pervasive computing tools, will be available in much more decentralized ways and at far less cost. The new visual tools will allow much more realistic forms of rapid prototyping in virtual and enhanced worlds. Visual computing will also allow many things to be visible that were invisible before.

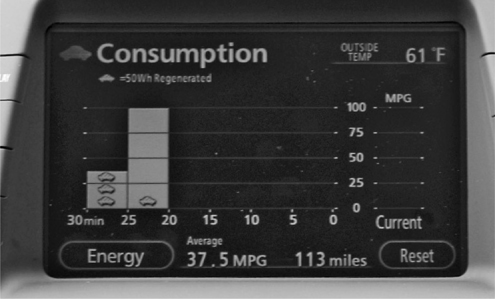

FIGURE 21. Dashboard of a Toyota Prius showing gasoline consumption. Source: Used with permission of Toyota.

An example is the dashboard of the Toyota Prius, Figure 21, which shows a real-time display of gasoline consumption while you drive. Behavior change happens best when it is influenced by immediate feedback, which is exactly what the Prius dashboard gives to a driver. In fact, it is sometimes difficult to concentrate while driving a Prius because it is so tempting to look over at the display and try to influence it with your driving. My guess is that that dashboard has saved a lot of fuel, but has caused a few accidents because the display is so engaging to watch. The Ford Focus hybrid uses the same principle, but the display—instead of a histogram—shows a leaf that wilts when a person is wasting gas, but looks healthy when the person is driving well.

Imagine a Prius-like or Focus-like dashboard that visualizes the measures that are most important for the organization you lead. Leaders could use this tool to test changes that you might make. In a virtual visual world, you could reap the benefits of rapid prototyping without the risk of actually making those changes out in the real world. Of course, there is the challenge of designing virtual world measures that accurately reflect the real world. It will not be as easy as measuring gasoline consumption.

A Rapid Prototyping Leader

Institute for the Future is located about two blocks from IDEO—arguably the world’s leading design firm—in downtown Palo Alto, California. IDEO is a model for rapid prototyping. “IDEO University” teaches rapid prototyping as a way of engaging people in the design and innovation process.

IDEO’s workspaces are unique. Founder David Kelley believes that design groups should be no bigger than about thirty people and that each studio should be designed in a way that adds to the creativity of the group. One design group used their office furnishings budget to purchase the tailpiece from an old DC-3 aircraft. Another purchased heavy curtains from a theater that was going out of business. My favorite studio at IDEO is a gutted Volkswagen bus rebuilt as a work environment, created as a joke on a designer while he was on vacation. This combination of good design and playfulness is stimulating and very helpful for rapid prototyping.

Rapid prototyping shows up in all the products that IDEO has designed. About a hundred versions of the Palm Pilot are on display at the Palo Alto office, from a crude foam cutout to a machine shop prototype to a commercial product. Seeing all of them together, one gets a sense of the evolution from first idea to final product. The failures along the way reveal lessons that get built into the next generation of the prototype.

IFTF has worked together with IDEO on several different projects. Thinking ten years ahead, we provide the foresight, which IDEO incorporates into their prototyping process. Essentially, we are looking for waves of social change that can be ridden by the product. David Kelley once commented to me that he likes working with futurists because, in the past, IDEO was sometimes called in so late in an industrial design process that they built great products that never should have been built in the first place. Now, IDEO is reaching upstream from industrial design to innovation. A ten-year futures perspective provides context for ethnographic studies of real people in their native habitat—the environment in which the new product will be used.

One project we worked on involved the creation of healthy, portable, and inexpensive food. First IDEO looked at current products. Cheerios with nonfat milk scored pretty well on the nutrition and price scales, for example—but they are not very portable. IDEO then combined consumer insight with foresight to help generate new ideas. From the first day of the project, they were roughing out prototypes, using any material that could be easily formed and reformed. Each studio has a tech box that contains materials that their designers have collected from all over the world to use in creating new prototypes.

IDEO has institutionalized rapid prototyping, though their designers have avoided over-standardizing it. This learn-as-you-go spirit lets the process of creativity happen without trying to control it.

Rapid Prototyping Summary

Rapid prototyping is a practical way to tap into the maker instinct. Leaders with maker instinct will get the idea of rapid prototyping easily and use it to succeed. The big challenge will be for them to accept failures as important ingredients of success and learn from them. Many leaders do not like failure of any kind, but in the future, they will have to change their expectations and learn to play through them.

Leadership in the future will be about high-speed, perpetual prototyping. The best leaders will be those who embrace the process and develop the ability to discern the patterns across the prototypes, the ideas that really do work. As Winston Churchill said, “Success is the ability to go from failure to failure with no loss of enthusiasm.”5

Rapid prototyping accepts failure as critical to success. Rapid prototyping requires enthusiasm to fuel the energy of innovation. Enthusiasm breeds innovation. Winston Churchill’s struggles with depression may have prepared him to survive failures with enthusiasm.