CHAPTER 20

Moving Smoothly into Action

Even if you’re on the right track, you’ll get run over if you just sit there.

—WILL ROGERS

Leaders take decisive and effective action themselves, and cultivate that ability in their people.

Bruce, the CEO of a government services firm, tendered his resignation when a charge (which was later dropped) was leveled against his $800 million company by a federal agency. This intense crisis could have forced the company into bankruptcy within weeks, and employees easily could have blamed Bruce. He chose to settle the matter by offering his resignation in order to save the company. Many companies turn on their CEOs amid scandal. However, because of the atmosphere of teamwork Bruce created and the results they had produced together, employees chose to praise Bruce in hundreds of unsolicited letters and emails:

Bruce’s leadership counted for more than just the success the company had achieved. More important, he left a bias for action as his legacy to the company.

Three themes occur repeatedly in these emails: the connection people felt with Bruce, how that connection motivated their actions, and how they link their success to his leadership. After you have built effective relationships, developed your people, and made great decisions, there is no limit to the power of the actions you and your people take. If you left your organization today under difficult circumstances, what feedback would you receive from your people? What actions would they take in your absence?

What Motivates Leaders?

When Bruce stared into the abyss of losing his position as CEO, his sense of responsibility for those he led, not money, was a motivator. In this pivotal moment, he chose to take decisive action to save the company. He resigned to preserve his people’s jobs and deferred the clearing of his name to a later time. He explained to us, “For me, leaving was not even a choice. We hadn’t done anything wrong, yet they insisted on having a sacrificial lamb. I was sad to leave; but it was an action I had to take, so I took it without hesitation. I knew that I’d get past this event professionally; but if the company had closed, thousands of people would not have fared as well, and that would have weighed heavily on me. Now I’m the CEO of an exciting new venture, so taking the right action has been rewarded.”

In your career, you probably have seen that leaders who are motivated by power, wealth, and perks produce stress in their people. In contrast, leaders who have a selfless vision of the future motivate their people to action and usually produce superior results. Bruce is one of those leaders whose vision was to achieve great things with his people. He created a special place for them to work and grow while they produced results for the company. As a result, they worked harder and longer than they would have if he had pushed them to meet purely financial goals—and they attained high levels of personal satisfaction too. They stayed when the going got tough. Respecting people as individuals and building relationships based on that attitude create connections that motivate effective actions and achieve personal and organizational goals.

Action or Inaction—It’s a Choice

Actions take place every day in your organization. How well do your people perform? What is your role in their actions? Do you set direction as a leader or get things done as a manager? Each action you take—or do not take—is a choice. Action and inaction are two sides of the same coin, and both are appropriate at times. You can take action to move your people ahead rapidly, or let the latent energy build while you wait to see which idea will triumph. Some actions are proactive; others are just a reaction to what your competitors, your customers, or your stakeholders have done. Your actions may deal with accomplishing objectives (management mindset) or pondering what else is possible (leadership mindset), or you may toggle between the two frequently.

Conversations about opportunities and issues usually focus on what, if any, action to take—the underlying assumption being that the action will be initiated as soon as possible. But it is equally important to take action at the optimal time. When you discuss start dates, ask your high potentials what they expect to achieve by their choice of date and why they favor that timing. Ask them to consider what other actions their people will be taking during that period, what timing would work best for their customers and their personal schedule, and how timing will affect the odds of a successful outcome—balancing all three is critical. Ensure that each new action will build rather than disrupt momentum. Bottom line: timing is equally as important for success as the technical feasibility and financial impacts of any new actions you consider.

No matter whether you are in planning mode or action mode, getting people to act in alignment and with passion and commitment is the essence of leadership. Motivating people to achieve seemingly impossible things time after time is what separates great leaders from also-rans. Organizations cannot accomplish the impossible—but people can and do. The ability of your organization to act will depend on the people you select, the relationships you build with and among them, how well you develop their skills and attitudes, and the decisions you make in concert with them. The effectiveness of all four of those leadership activities depends on the quality of your conversations.

The Context for Action

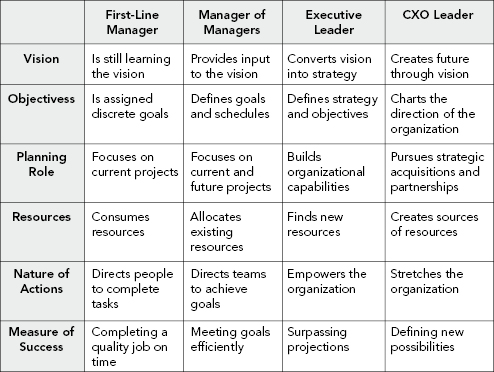

Figure 20.1 shows the different contexts within which managers and leaders operate relative to their roles in taking action. In general, managers deal with the known and tangible, whereas leaders deal with the future, create the vision and strategy, and provide the resources to implement the strategy. Efficient managers measure results quantitatively; transformational leaders look at qualitative measures.

FIGURE 20.1. The Context for Action.

Managers and leaders have different contexts for the goals they set, the actions they take, and the results they seek to produce.

Organizations are operating in a management mindset when they (1) incrementally improve yesterday’s actions; (2) work substantially within existing markets, boundaries, and resources; (3) focus on tasks and numbers; and (4) are satisfied with their current level of success. Conversely, organizations are in a leadership mindset when they (1) enter new markets, (2) create and market innovative products and services, (3) engage in transformational thinking, and (4) unleash their people’s strengths by providing coaching and mentoring. Obviously, both mindsets are needed to produce both short- and long-term success. By holding conversations that stretch boundaries and tap new resources, the leadership mindset creates the new rather than incrementally improving the old. Then the management mindset efficiently implements the plan that supports the short- and long-term strategy.

An All-Star Team Isn’t Enough

Among Major League Baseball’s thirty teams, the New York Yankees annually have the highest payroll. It generally exceeds $200 million for the twenty-five-man roster—most starters earn over $10 million a year. There is a current or former all-star at almost every position and several on the bench as reserves. Yet in the ten-year period from 2002 to 2011, the Yankees won the World Series only in 2009. Even high-potential all-stars must perform as a team to realize their full potential. Aligned actions are as critical to success as the skills that each high potential possesses. Hiring the most talented people does not guarantee teamwork or success—leadership and aligned actions do.

Many executives use precise metrics to measure individual and team performance. When it falls below targets, they try to upgrade the team by focusing on the weakest department or weakest people. They try to improve their performance or replace them with superstars. The underlying assumption is that if you hire experts, the results will take care of themselves. As the Yankees’ record demonstrates, that assumption is false. A team needs leadership and vision in addition to talent, especially when it must face fierce competition, market shifts, and new technologies. Two core measures of a championship team are (1) how well the team members align with the team’s goals and each other and (2) how much they believe and trust in each other. How often does someone on your team act independently despite your best effort to create alignment? How could you harness that independence to support the team’s success and achieve its goals?

Teamwork is essential for success. When you hear complaints that executives feel as though they are “herding cats,” that agreement is difficult to forge, that communications are muddled, or that high potentials are stagnating, you are hearing telltale signs that teamwork is missing. Leaders work in concert with each other and with their high potentials to align everyone’s actions with the mission. When teamwork is missing, then silos compete for resources, and consensus takes a backseat to the struggle for power and control. Conversely, when all segments of an organization are aligned, then healthy conversations help everyone produce extraordinary results.

The Plan-Results Gap

Late one afternoon, we met with a government executive, George, in his corner office. He looked tired when he confessed, “I’m frustrated. It’s been a year since we held that strategic planning off-site, and there is still a huge gap between our target and actual results.”

The off-site was held in an ideal setting and had included stakeholders from all divisions of the enterprise. The meeting’s agenda clearly addressed the agency’s core challenge: to cut costs and invest in the future. George was at a loss to explain why the strategic initiative had stalled. Everyone understood the urgent need for change and embraced the strategic plan. He lamented, “Our top leaders were there—our best and brightest. They were empowered to take action. We aligned our incentives and resources with change. Commitment was high. But a year has gone by, and we aren’t even close to our goals.” His question was, “What did I miss?”

Unfortunately, we have heard similar frustrations from other capable, experienced, and committed leaders who understand the difficulty of change and seemingly have done all the right things. Even with a superb staff and a clear vision of the future, they fail to achieve the desired results. When the shortfall becomes common knowledge, their credibility inside and outside the organization evaporates, and people become cynical about change. Of course, what they are missing is effective conversations about converting decisions into action.

The business world is littered with programs that failed despite huge investments. They are launched with optimism and fanfare—then fall to the wayside. The bottom line is that, without effective conversations, the organization wastes time, money, and focus. It would have been further ahead if it had not attempted the change in the first place. Leaders must own these initiatives, ensure that they are designed properly, and hold regular conversations about them to inspire others to take action.

Executives often spend too much time developing a brilliant strategy and too little time planning how they will implement it and measure progress. These executives participate in well-planned strategic workshops and leave in agreement on the steps to be taken. Yet fundamental change rarely takes place. Lack of committed action is the root cause of this pattern every time. Action is more than a plan, a schedule, and accountability and control mechanisms—although those elements are essential. Action is a discipline embedded in the culture that aligns and drives people to do what is required to achieve specific, agreed-on goals.