3. Global Connectivity and Socioeconomic Leveling

Whether you are a top-level executive or an undergraduate business student, chances are you have heard the term BRIC. The acronym stands for Brazil, Russia, India, and China. These countries are grouped not only because of their landmass and population size, but also because they share similar economic development characteristics and occupy comparable positions in the industrialization process. These nations do not yet occupy the same economic status as the United States, Germany, Japan, and other highly developed industrialized nations. However, the BRIC countries are poised for steep productivity growth—especially when you consider the rapidly accelerating conditions fostering local consumerism.

Consider Brazil, the country described by the acronym’s first letter. With 192 million citizens, Brazil is the world’s fifth-largest country in terms of population, behind only China, India, the United States, and Indonesia. Brazil is developing as an economic power because its massive population has become a vital consumer base for the world’s goods and services. Its citizens’ willingness to consume was tacitly recognized when the nation was named host of the world’s two largest athletics competitions: the 2014 FIFA World Cup and the 2016 Summer Olympics. That makes it the first South American country ever to host both events, let alone having them back-to-back. Viewing FIFA’s and the International Olympic Committee’s historical choices, South American countries have in recent times been a relatively unpopular destination for the games. Yet Brazil’s staggering economic growth has certainly changed their minds, and it’s likely that soon, sports won’t be the only thing feeling the country’s commercial influence.

Economic thinkers dating as far back as Aristotle suggest that the leveling of a population’s economic status is key to sustaining a healthy economy. Leveling represents the narrowing of a nation’s monetary distribution such that more people have significant consumption power. Generally, this means that the state in question has a large, burgeoning, economically viable middle class. That’s because, when customers enter their country’s middle class, they tend to consume high-status goods at increased rates. To say that contemporary Brazil’s middle class meets all of those criteria would be an understatement. In late 2011, the Brazilian government reported that its middle class had expanded to 95 million people. That’s half of its entire population. Much of that growth occurred from 1999 to 2009, when 31 million people entered its middle class. Economists anticipate that, by 2014, just five years later, another 20 million Brazilians will achieve the same financial power.1

1 Tarrisse, Isabel. (2010). “Brazilian Middle Class Reaches 95 Million, Represents Over Half of Population.” Brasil.gov Press Releases. Secretariat of Strategic Affairs of the Presidency of Brazil (SAE). “Brazil’s middle class in numbers.” (2010). Brasil.gov Press Releases.

Brazil’s middle class isn’t just large—it’s economically powerful. The Brazilian middle class controls an astonishing 46.24% of the national population’s purchasing power. This statistic alone poses a slew of supply chain management issues as companies around the world are rushing to meet the nascent market’s demands. The middle class also possesses 70% of the country’s credit cards, and with credit so widely available, the demand for more statured goods is bound to grow. We also cannot ignore that, of all Brazilian Internet users, the middle class accounts for 80% of them, and many are shopping online. Just as American automakers of the last decade learned that they could not survive without competing in China, the online Brazilian market could emerge as the next consumer frontier. Companies that want to serve it need to understand its game-changing potential.

Brazil is just one example of global economic leveling happening today. Its middle-class income bracket alone is larger than most countries’ entire populations. With more discretionary income at their disposal, more credit at their fingertips, and widespread Internet accessibility, it is inevitable that consumption will continue to surge. But Brazil is not the only nation where economic leveling is happening. Internet proliferation is yielding worldwide access to product and service information. Whereas many international markets traditionally have been characterized by localized production and consumption, this kind of accessibility gives us reason to believe that their future counterparts will be much more globalized. If they do, globalized markets and growing populations will begin to unravel the assumptions that underpin our current supply chain systems. These forces will geographically scatter demand around the globe and thereby require longer, more sophisticated supply chains to balance supply and demand.

However, not everyone agrees that the world economies are, or will be, as globalized as some predict. Before we begin to address the supply chain challenges of the future, we need to understand the two most prominent perspectives of the globalization argument.

Is Globalization Real?

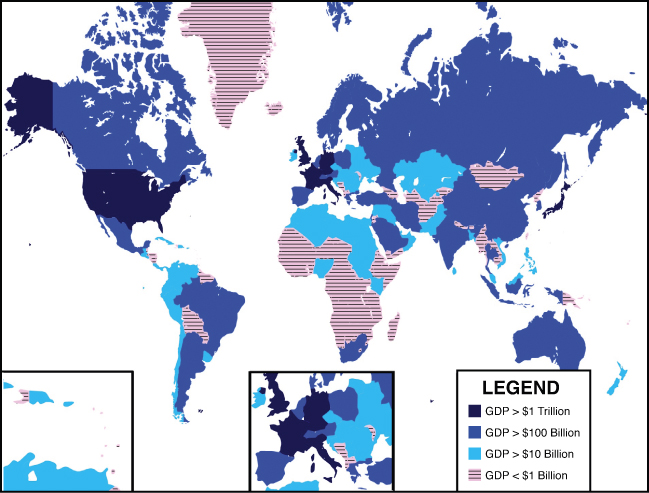

Since the United States’ Industrial Revolution and then throughout much of the 1900s, the global economy was structured as somewhat of an oligarchy. A small number of nations produced the bulk of the world’s goods and services, consumed the most finished products, expended the most natural resources, and held the most significant wealth. This was the world economy as most of our parents and grandparents knew it, and it was stable in this form for nearly a century. The preponderance of global commercial activity revolved around North America and a few European countries, with Japan bursting onto the scene in the latter part of the 20th century. Lesser economic presences were also emerging in South America and the Middle East’s more developed nations, and Australia was also showing signs of life in international commerce. Even at the end of the 1900s, as shown in Figure 3.1, a very small percentage of the world’s 200-plus nations represented almost all of its consumption and demand. In most cases, markets were still localized, and although global trade had always played a role (albeit limited), the vast majority of the world’s commercial activity could be described as domestic.

Figure 3.1. Global GDP, 1995–2000 means

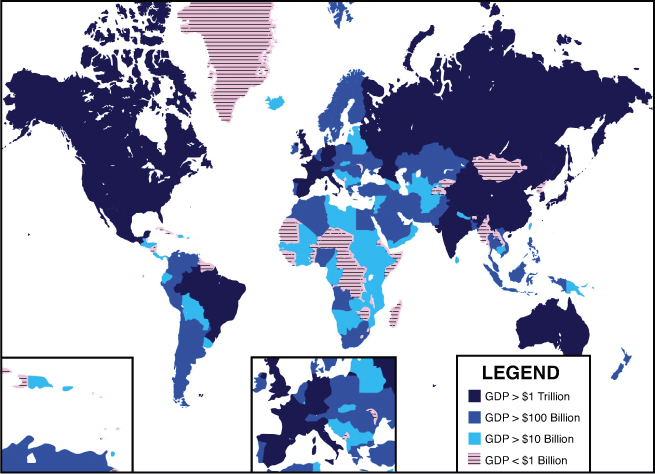

Just before the turn of the 21st century, though, a number of extraneous forces converged to revolutionize global commerce. First, as described in Chapter 2, “Global Population Growth and Migration,” many nations’ populations began to grow nonlinearly and nonuniformly, with some nations rapidly outgrowing others due to organic growth, migratory growth, or both. At the same time, significant geopolitical barriers were falling, buyers and sellers were being granted greater market access via the Internet and global connectivity, and services were being outsourced—first to other companies and then to other countries. Suddenly, as shown in Figure 3.2, many more nations established global economic presence where it hadn’t existed before, the BRIC countries among them.

Figure 3.2. Global GDP, 2011

Interestingly, these forces affected different nations in different ways. India suddenly became prosperous because of its population’s connection with Western business ideals (often learned in Western business schools), as well as its citizens’ willingness to work for wages much lower than those overseas. Eastern Europe became a viable commercial node after the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, and despite its lower-educated workforce, the region thrived because of its cost advantages. Technology made outsourcing to low-cost nations possible because workers could communicate in real time with their overseas employers. Outsourcing to these regions thus became a viable business strategy, but the work outsourced from one place to another would differ based on the labor pool’s educational attainment. (Some nations could perform more socially sophisticated customer service management tasks, whereas others would be hired to perform labor-intensive manufacturing.)

Thomas Friedman’s 2000s books, The World Is Flat and Hot, Flat, and Crowded, fueled much public discussion about the forces that brought about these aspects of business globalization. In the books, which were highly touted by business leaders and regular readers alike, Friedman made several seemingly uncontroversial claims related to the world’s rapidly increasing interconnectedness. In a nutshell, he associated Internet-enabled technologies like file sharing, weblogs, workflow software, Voice over Internet, and “Googling” with the aforementioned outsourcing and geopolitical smoothing trends. He concluded that these forces were responsible for radically decreasing the previous century’s economic isolationism barriers. Friedman admitted that his writings’ purpose had little to do with how to conduct global business activity per se. But many of the world’s economists agreed with his basic premise: As technology diffused around the world and leveled the playing field, economic prosperity would soon follow in the nations and regions that best harnessed it.

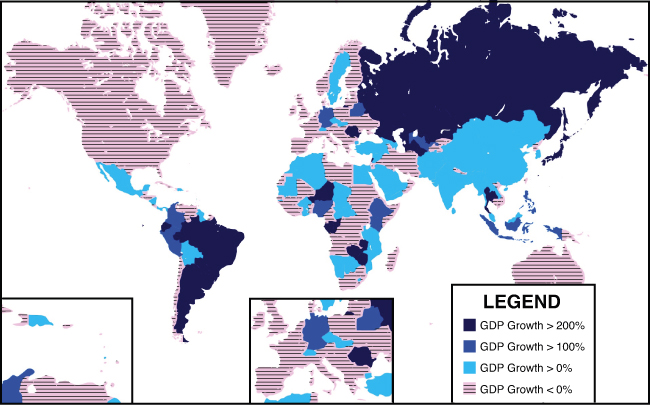

Does evidence support Friedman’s position? In the early 2000s, did the world suddenly become “hot,” “flat,” and/or “crowded”? At first glance, it would certainly seem so; we have already conceded the “crowded” aspect, and Chapter 4, “The Changing Physical Environment,” has plenty to say about the Earth’s being “hot.” When we study Figure 3.3, we can see that, over the past two decades or so, GDP changes have been greatest in the areas encompassing BRIC nations, as well as some areas of sub-Saharan Africa. We could conclude that the world’s economies were—and still are—rapidly leveling. The nations that were formerly economically powerful (those with the darkest shading in Figure 3.1) appear to be stagnating rather than growing at (remarkably) the same time as the new economic powers are taking flight. It only makes sense, then, that Friedman’s lexicon is mostly true, and that the world could indeed become “flat” if it is not already. Right?

Figure 3.3. Change in GDP, 1995–2010

We generally agree with Friedman’s underlying promises, but alas, his work has not escaped criticism. Several authors opposed to his ideals soon joined the literary fray, armed with the one weapon they claimed Friedman lacked: hard data. Almost immediately following the 2005 publication of The World Is Flat, magazine columnist and George Mason University professor Richard Florida, along with some of his geographic science colleagues, illustrated the fallacies that can arise when conducting economic analyses of globalization using growth percentages instead of absolute numbers. Florida and his colleagues published an article in The Atlantic magazine. They pointed out that although populations are growing and technology is spreading to new parts of the world (especially those within Figure 3.3’s darker shaded areas), these types of growth were not actually yielding much economic production or consumption. Nor did these areas produce noticeable patent or scientific citation growth, two of the leading indicators of economic development. In fact, the analysis performed by Florida et al. showed plainly that although economic activity was beginning to accelerate in developing nations, these countries had started off far behind their predecessors in terms of rote productivity and consumption. Their implication was that even quick and sizable growth would do little to meaningfully close the gap between the traditional powers and developing economies, at least in the near future. The authors were convinced that Friedman’s globalization idea was essentially an anecdotally driven myth, but they did suggest that it was useful to consider as more meaningful development continued to occur.

Subsequent reviews of the Friedman school of thought arrived at similar conclusions. His two books became the focal point of scholarly circles’ harsh criticism, which culminated when Harvard business professor Pankaj Ghemawat published World 3.0 in 2011. In this book, Ghemawat proposed that the business world is not as globalized as many contemporary thinkers would like to believe. Citing data drawn from a variety of public sources, Ghemawat develops a compelling argument that positions the globalization conversation spurred by the Friedman books (and their advocates in the punditry) as nothing more than media hype. In so arguing, Ghemawat noted that only 17% to 18% of Internet traffic crosses international borders, that the world economy’s export-to-GDP ratio is but 20%, and only about 20% of all equity investment is international. These statistics are far below what a Friedman proponent might expect. As a result, Ghemawat contended that the 2009 world could best be construed as “semiglobalized.” Therefore, business entities needed to consider strategies that leveraged both national homogeneity and international differences to prosper abroad.

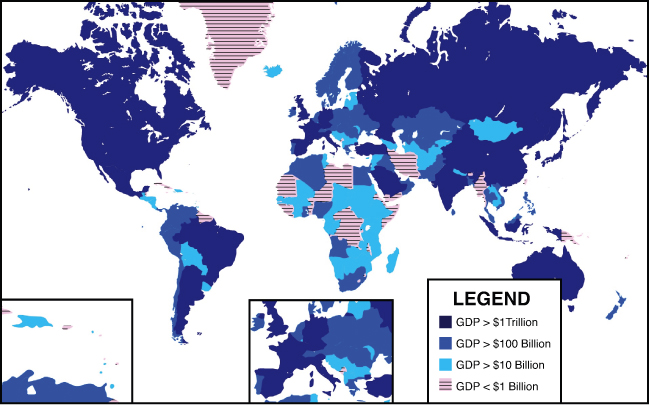

As authors of a book about managing the supply chains of the future, we are most interested in the current status and future trajectory of global demand and supply. The evidence presented by Friedman’s detractors—Florida, Ghemawat, and numerous others—distills to a compelling argument against the current existence of a fully globalized world. But it is also entirely possible that history may judge Friedman as being more right than wrong, with the lone delinquent factor simply being the amount of time it will take for the world to achieve true global integration. With our interest piqued by this possibility, we conducted one more analysis, the results of which are shown in Figure 3.4. Here, we extended the most recent 15-year growth curve another 15 years into the future. That is, we took 2010’s absolute GDP (the same data used to compose Figure 3.2) and applied the most recent population and GDP growth data available to see what might happen if the current state of affairs continued in straight-line fashion.

Figure 3.4. Global GDP, 2025 (projected)

The results, and their implications for future supply chain managers, are quite interesting. Several modern international powers—like the United States and Canada, Europe, and the BRIC countries—could be expected to sustain their growth or stagnate, with China overtaking the United States as having the world’s highest GDP. Many countries that surround these areas also see impressive gains. Take a look at the islands between the Pacific and Indian Oceans. While many of these had a GDP above $100 billion in 2011, by 2025 our projections show them to have surpassed the $1 trillion mark. The Middle East, South America, and Africa are also expected to sustain their impressive numbers.

Though the 2012 edition of planet Earth should not be construed as fully globalized by any stretch of the imagination, the forces Friedman described do seem to be having at least a marginal impact on global commerce, only a few years after his books’ emergence. Furthermore, based on our own, very conservative forecasts, it appears that incremental increases over the next 15 years could reveal a “new world order” in terms of economic activity. Children in nations formerly disregarded as economic also-rans are witnessing consumerism as the Information Age provides worldwide consumers access to all kinds of product and service information. Like Friedman, we are speaking anecdotally, but consider that in some places in Africa, kids are introduced to cellular devices before their village even has physical infrastructure. Since there’s also no electricity, they walk miles to charging stations and pay to recharge their phones.2 In these parts of the world, technology is outpacing many other modern developments, and intermediate developments are being leapfrogged as the most advanced technologies show up in the most remote villages. Therefore, a new consumer generation is growing up around the world with perspectives toward consumption that businesses never would have dreamed possible before the turn of the century.

2 Steele, Chandra. (11 May 2012). “How the Mobile Phone Is Evolving in Developing Countries.” PCMag.com.

Of course, any change in global economic power that will influence global demand patterns will also increase the strains on the world’s natural resources and process inventories—things that are already under great pressure. In China, consumer beef eating has made water more scarce than usual, because beef takes a great deal more water to produce than rice and vegetables. Despite the fact that China has constructed over 85,000 reservoirs in the last 60 years, nearly 400 of its 600 largest cities suffer from water shortages. This trend can only continue as China’s growing middle class demands more beef, more produce, and more of other natural resources. Therefore, these products must be produced in and/or moved from places with production excesses to places where shortages commonly occur. As a result of its problems, China has turned to high-quality beef exports from the South American country of Uruguay to sate its demand.3 McDonald’s has set a goal of having 2,000 restaurants in China by 2013 (as of 2011, it had 1,356). The fast food giant will look to Australian suppliers—not U.S.-based ones—to get beef for its Chinese restaurants.4

3 Peters, Mike. (25 June 2012). “China’s appetite grows for meat from Uruguay.” China Daily: USA.

4 “Australian beef farmers set to benefit from McDonald plans to expand in China.” (17 August 2011). MercoPress: South Atlantic News Agency.

We see one big question—and it’s one of our prevailing themes. What if one day every child in every developing country grows up wanting cheeseburgers, flat-screen TVs, and other production outputs their parents and grandparents never had access to and maybe never even dreamed of owning? What will this mean for the companies charged with delivering those goods in the right form, at the right place, and at the right time via their global supply chains?

We need look no further than the Middle Eastern country of Pakistan for a hint of the future. As of 2011, the Pakistani middle class accounted for 35% of the nation’s population, or approximately 63 million people. Fascinatingly, the Pakistani median age is 21.1 years, which is far younger than the world median of about 28 years. Given this expanding and surprisingly youthful middle class, we would expect a different kind of Pakistani consumer to emerge—one who will have the most disposable income in his or her national history. When considered in aggregate, these new consumers would represent a suddenly viable market segment possessing wealth not unlike that of modern-day Netherlands or the Czech Republic. As exuberant new consumers, the Pakistani middle class is starting to consume goods that reflect their youthful demand. In 2011, Pakistan saw sales volume and import increases in TVs (+28.6%), automobiles (+14.6%), and fast-moving consumer goods (+9.3%) versus its previous three-year period.5

5 Ahsan, Afnan. (May 2011). “Business and the Middle Class in Pakistan.” Planning Commission: Government of Pakistan. “Pakistan: Framework for Economic Growth.” Planning Commission: Government of Pakistan.

In Nigeria, Ethiopia, and Egypt, African nations already among the world’s top 15 most populous, converging GDP and population factors are slowly developing them into global consumer forces to be reckoned with. African incomes have yet to catch up to those of other developing countries, but many of today’s Africans do have dispensable income—and, as with Pakistan, they are becoming experts at spending it. As of 2012, nearly 343 million Africans were considered middle class. Only four short years ago, they spent $830 billion on consumer goods alone, and that rate continues to grow. The International Monetary Fund predicts that, by 2030, these highly populated African countries will spend $2.2 trillion dollars a year.6 Yet few global companies are ready and able to serve customers in these places. And the anecdotal evidence we collected from managerial interviews in preparing for this book suggests that the leaders of companies headquartered in developed nations are struggling to consider—even deigning to believe—that markets such as Pakistan, Egypt, Ethiopia, Nigeria, and even Paraguay will always present economically viable opportunities, even when more fertile masses of potential customers are nearby.

6 Hatch, Grant, Pieter Becker, and Michelle van Zyl. (2011). “The Dynamic African Consumer Market: Exploring Growth Opportunities in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Accenture.

We believe that modern global firms ignore such nations at their own peril, and that the way to succeed in these kinds of markets is through adequate forethought related to supply chain design. Although the world is not yet flat, it is flattening, and modern companies need to start developing plans to serve an ever-broadening customer base if they want to remain prosperous.

The forecasted interconnectedness of the world’s commercial systems presents a multitude of challenges for managers seeking to deliver products optimized for efficiency and effectiveness. Many factors are affecting demand in previously infertile markets due to two forces in concert with the aforementioned population changes: Internet proliferation in places where it was previously largely inaccessible, and disposable income influxes to these same places as a result of increased GDP.

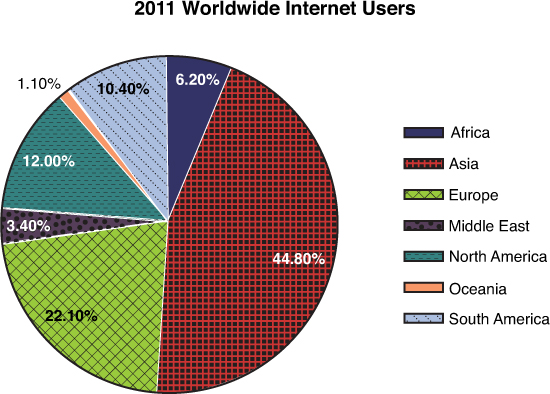

While Internet commerce and dot-com companies were exploding onto the international scene in the 2000s, Africa was only just receiving the technology that would make access to the World Wide Web possible. It wasn’t until 2009 that African-owned Seacom installed an undersea fiber-optic cable that connected East Africa to Europe and parts of Asia.7 Meanwhile, in southern Africa, the broadband market is woefully underserviced but still expects to haul in $19.08 billion by 2017,8 a 405% increase from 2010.9 In fact, in the period between 2000 and 2011, the percentage of Africa’s population on the Internet increased by 2,988%. This usage statistic tops all continents, but other areas, like South America and the Middle East (regions with notable growth in Figures 3.1 through 3.4), aren’t far behind. Africa still makes up only 6.2% of the world’s Internet users, as shown in Figure 3.5. Nevertheless, its astronomical growth, combined with GDP and population projections, shows that the Internet will bring wealth to these countries, which will, in turn, encourage the Internet’s further propagation.

7 “East Africa gets high speed web.” (23 July 2009). BBC News.

8 Miniwatts Marketing Group. (2012). “Internet Users in the World.” Internet World Stats.

9 Moyo, Admire. (13 July 2012). “Southern African broadband market to hit $19bn.” ITWeb: Enterprise.

Figure 3.5. Worldwide Internet users, 2011

What will Internet propagation mean for companies seeking to do business over the next quarter century? Many businesses, especially smaller ones, have always been localized and will continue to be. But for the majority of commercial enterprises, the Internet represents the best, and perhaps lone, source of worldwide demand generation. Until the early 2000s, shopping was almost strictly a local phenomenon. But just a decade later, we now search for goods worldwide—and can compare specifications, quality, and prices of offerings located continents apart in seconds. Notwithstanding the extent to which this capability has reduced businesses’ ability to commit consumer arbitrage, these issues have massive implications for global supply chain design. After all, it’s one thing to find buyers for your goods in a faraway country. It’s another thing entirely to develop an economically viable capability to serve them with the accuracy, speed, and service that match their down-the-street retailer.

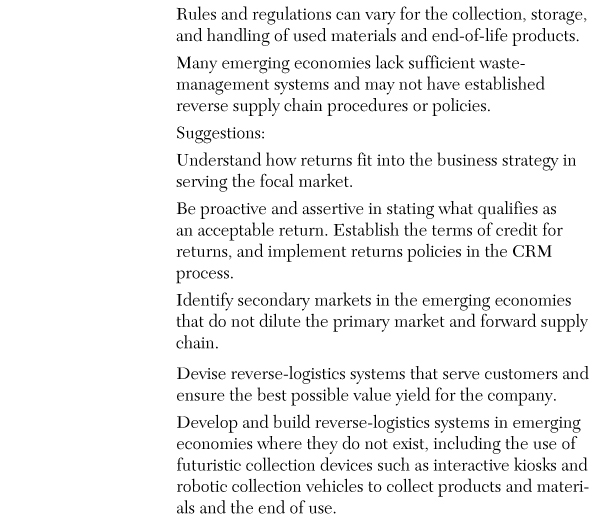

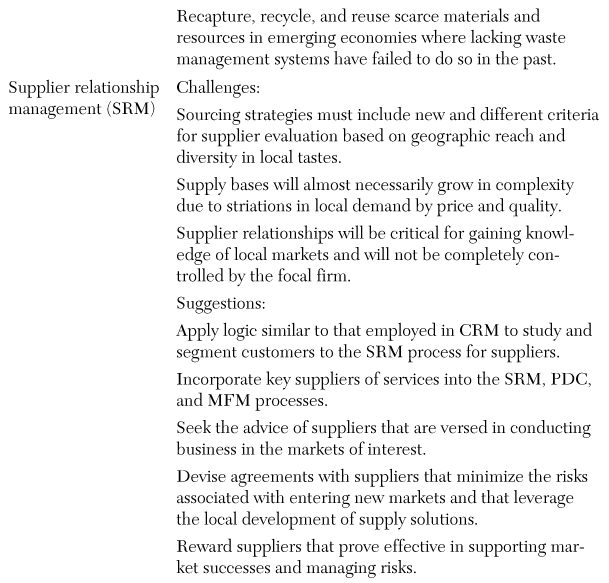

We believe that prominent demand shifts will happen as a function of population growth, Internet access, and the accruing wealth in traditionally dormant markets around the world. Based on these factors, we can deduce that supply and demand are poised to drastically slip out of alignment in the foreseeable future in locations like Brazil, Pakistan, Egypt, Nigeria, and Paraguay, among others. Each of the eight GSCF supply chain processes therefore is susceptible to risks associated with global economic leveling. We will address them in turn.

Economic Leveling and Connectivity Issues for Future Supply Chain Managers

As we have noted, the balancing of supply and demand is both precarious and essential to business success. Populations are growing and migrating, but they are also becoming more interconnected and economically level. Along with the leveling of production and consumption power comes a leveling of consumer expectations for what constitutes quality products and service. We see the following as key issues related to the connectivity and leveling of global demand centers, for consideration in supply chain planning efforts in the forthcoming years:

• Developing a significant online selling presence will be almost mandatory to succeed in mature or highly competitive industries.

• Customers will become more homogenous worldwide in terms of tastes, preferences, and price sensitivity as time goes on. They will be less homogenous within populations, nations, and segments in the short term, therefore requiring greater assortment.

• Many products will become commoditized earlier in the life cycle, so competition based on logistics and supply chain services will serve as a critical differentiator.

• Global visibility of offerings will require the expansion of supply chain networks into places never before considered and will lead to some of the few remaining growth opportunities in goods industries.

We differentiate the issues related specifically to increased global consumerism and connectedness from those that are associated purely with population ecology. Future supply chain managers are advised to consider these issues in supply chain network design and demand planning to better effectuate DSI. Table 3.1 lists each process and describes its potential implications.

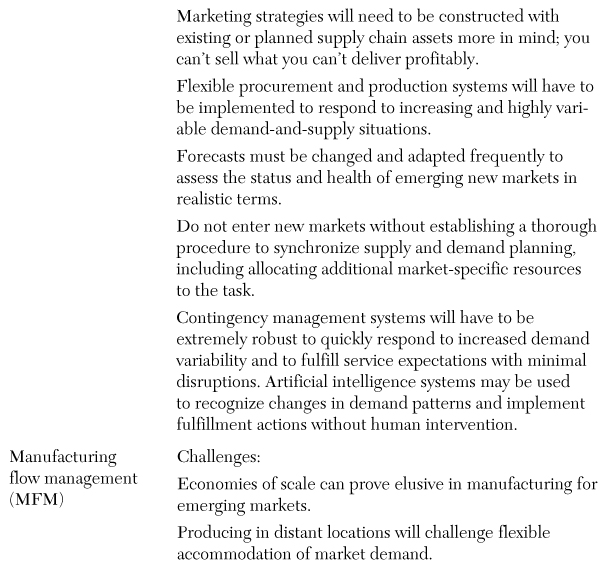

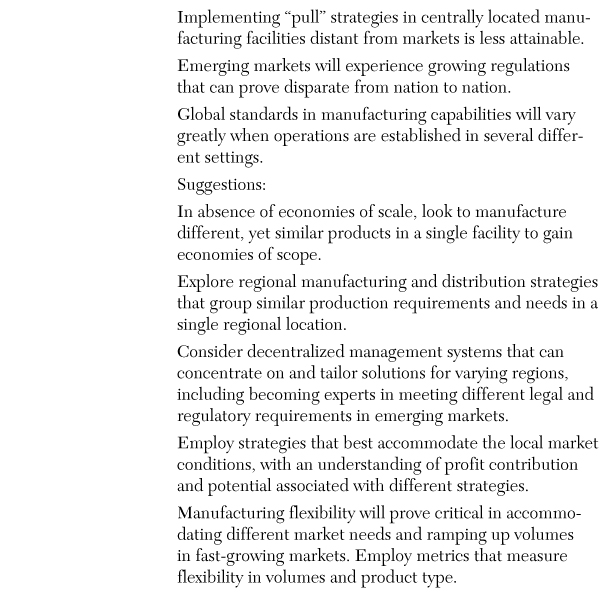

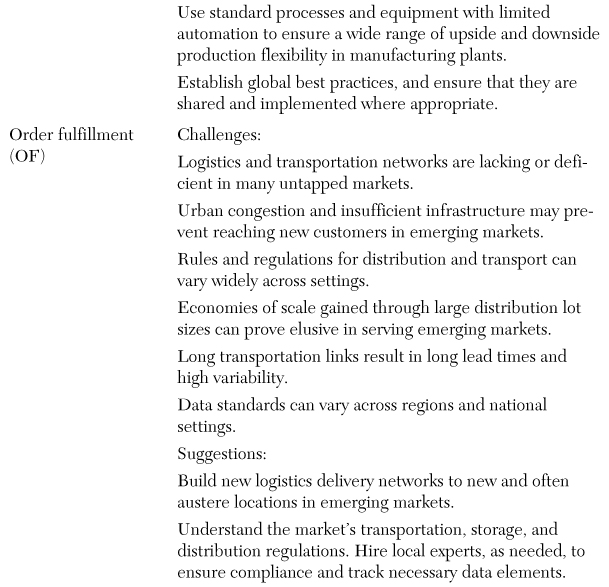

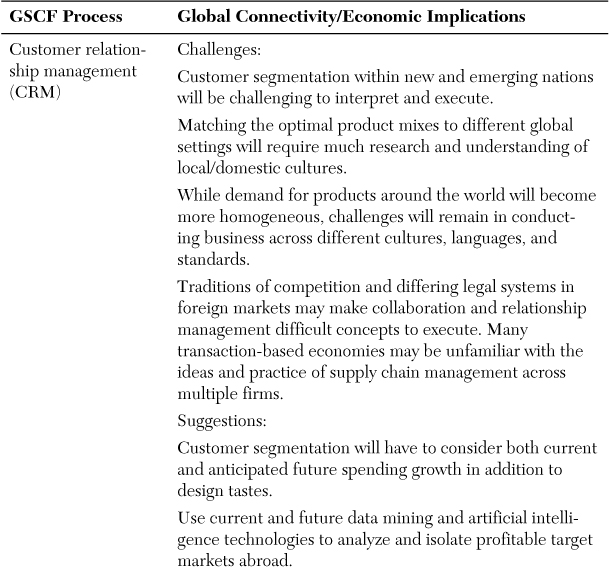

Table 3.1. Global Connectivity and Economic Leveling Implications for SCM

Customer relationship management is at the forefront of addressing globalization and socioeconomic leveling. As supply chain managers learn to conduct business among an emerging set of nations, they will be forced to adapt to new ways of approaching markets and the prospective customers that embody these markets. Western companies cannot expect that their counterparts will embrace the beliefs and practices that are brought to the conversation, nor should the non-Western companies simply roll over; their emergence among the global business elite validates them. Rather, a convergence of values, priorities, understanding, and practices will spell victory for firms trying to navigate a flatter world.

Calculating where to place speculative bets in prospective customer relationships presents the greatest challenge. Companies will face countless such investment opportunities, but knowing with whom to work closely and develop extensive, mutually intensive relationships is key. Rather than relying on historical precedent, supply chain managers will be pressured to identify choice prospects among the masses. Beyond sales and profit potential, however, “choice” customers are those that offer the best competitive position and allure through their influence in the market. They will possess knowledge, technology, and other valuable resources. They will prove compatible as business partners, but they may require considerable development and investment. To wade through these complex determinations, companies must employ advanced methods of data mining and artificial intelligence analytics to isolate the most promising targets for pursuit.

Conducting business with companies in emerging markets will be ripe with uncertainties, however, because the sheer number of unforeseeable circumstances in working with new partners could prove debilitating. The customer service management process will be forced to imagine the realms of possibilities and identify prospective issues in product and service provisions for which no precedent exists. That said, product-service agreements must be entered into with one’s eyes wide open, understanding that close relationships will call for extensive handholding with customers. Beyond the basic provisions, the firm must be prepared to offer knowledge about navigating complex regulations, different languages, currency risks, divergent terms of trade, assorted or nonexistent information systems, and a host of cultural differences.

The more extensive the relationship, the higher the stakes and the more that can go wrong, so the need to act on customer knowledge and appreciate the risks involved is clear. Yet here too, advanced information technologies can aid the cause by providing databases populated with essential customer data that supports responsive, attentive service. Supply chain event management systems should be employed to detect small departures from acceptable service parameters before they result in major problems and complaints. Beyond merely dealing with problems when they occur, however, you can use simulation technologies to conduct scenario planning.

Among the most anticipated scenarios is the imbalance in supply and demand. With consumption on the rise, patience with shortages and stockouts will be minimal. Demand management will place a premium on flexibility, because forecasts will be highly susceptible to error in new markets. Positioning inventory in the emerging market can be costly and, by its mere presence, can discourage a company from gaining intimate knowledge of customer issues and buying habits. Rather than leveraging inventory as an insurance policy, companies are encouraged to collect and disseminate critical demand information. Information technologies can help here, too, but companies are encouraged to develop grassroots understanding of market matters and individual customers. This understanding can be leveraged in improved forecasting techniques. The qualitative inputs of people on the ground and close to the market will prove most adaptive to rapidly changing markets, as opposed to relying on data-driven methods that emphasize historical market developments.

All companies can expect, however, that it will take some time to gain comfort in newly emerged markets. The flexibility espoused by the demand management process will be called on to close the gap of demand management capabilities. Along those lines, flexibility in manufacturing is central to providing supply chain flexibility. Yet manufacturing products in distant locations complicates flexible response to disparate market needs, because variety in products and packs overwhelms most production systems. Manufacturing systems designed for large-volume production and bulk packaging struggle when facing a completely different set of market circumstances. Consider, for instance, North American health and beauty supply manufacturers accustomed to producing shampoo in 23-ounce bottles. This quantity might supply a typical North American consumer for a month or longer. However, the manufacturer finds that consumers in India prefer to buy shampoo in single-use packets, and they are willing to pay only a few pennies. Rigid manufacturing systems designed to produce large lot sizes will struggle to accommodate the Indian market—particularly if production occurs half a world away. The transportation cost alone from a factory any distance from the local market would usurp the expected purchase price. Yet production in the local market is challenged by a lacking production infrastructure, dwindling water resources (as described previously), and frequent power outages. The widespread blackouts that occurred on two consecutive days in July 2012 wiped out power for more than half of India’s 1.2 million-person population.

The question of where to manufacture products to serve emerging markets will continue to challenge companies. Though manufacturing is among the most value-intensive steps in the supply chain, companies over the past two decades have searched far and wide for the lowest-cost location in which to perform these operations. Often they outsource to distant locations. Low-cost locations are defined largely by the cost of labor. U.S. firms sought the skills and favorable economics of Mexican labor in the latter years of the 20th century. More recently, China has become the manufacturing center for everything from whimsical tchotchkes to high-tech consumer electronics like the Apple iPhone. A study conducted by AMR Research indicates, however, that 56% of supply chain executives surveyed indicated that the total landed costs of their products increased markedly as a result of offshore operations.10 This result can be attributed to the increasing cost of doing business in China associated with rising labor costs, higher material costs, and appreciation in the Chinese currency. Along with these direct economic movements, the added complexities involved, and longer and more variable lead times, losses in visibility and control combine to increase inventory holdings and impair service.

10 “How Hybrid Sourcing Can Lower Costs.” (1 March 2011). Materials Handling & Logistics.

The future will hold some fascinating developments that could offset these forces. Expect the formation of regionally tailored manufacturing campuses, designed with excellent manufacturing flexibility, to accommodate different market needs and ramp up volumes in fast-growing markets. Competing campuses will race to see how many days it takes to increase output by 50%, or how many hours it takes to tool for a completely new product. Perhaps most exciting is the development of radical new manufacturing technologies such as 3-D printing to capture maximum production flexibility with a more limited logistics footprint. 3-D printing is a reality today for simple products with limited volume. The question is how long before these radical technologies support more complex items in market volumes at competitive speeds.

Like manufacturing flow, order fulfillment can also be especially challenged by socioeconomic leveling and the exploration of new markets. Economies of scale in order picking evaporate when orders involve small quantities, like cases or “eaches” (individual items), as opposed to pallets. Similarly, economies in transportation in emerging markets means effective utilization of motorbikes, as opposed to large trucks and railroads. Value stream map analyses of distribution operations in emerging markets illustrate that it is in the final stretch of the supply chain (from distribution center to retail) that service implodes and costs explode. Solving this “last mile” problem will only grow in importance in the coming years as the frequency and urgency of the problem increase and the world becomes more urbanized and congested.

Look for the triumphant return of two technologies that have fallen out of favor in recent years. Automated storage and retrieval systems (AS/RS), such as robotic cranes and vertical carousels, gained popularity in the 1980s and 1990s as a way to handle large volumes with minimal human engagement. The application of these technologies faced challenges, however, in accommodating mixed pallet loads, which became increasingly common among large retailers that could demand them of their suppliers. The automated equipment was designed to process full pallet loads and enjoyed limited flexibility. Some companies shuttered the technology despite the sunk investment. Pressures to support urban populations in crowded downtowns will encourage the construction of high-rise facilities that consume a small footprint. The capability of automated facilities to provide flexible order fulfillment will be essential in this development.

Supporting this flexible accommodation will be passive radio frequency identification (RFID) technology. RFID was all the rage in the early 2000s. Supply chain superpowers like Walmart, Metro AG, and the U.S. Department of Defense established aggressive RFID mandates that they later retracted to various degrees. Vendors resisted firmly when they realized that the tags and readers were quite expensive and not achieving perfect read rates. Continued development of the technology and increased scale are helping to improve both the economics and capabilities of RFID. Paired with AS/RS, RFID provides smart and agile order fulfillment.

Logistics networks will adapt to serving emerging markets too. For instance, distribution facilities might be located in unconventional locations, like atop parking structures and multifamily housing units. Delivery modes might also evolve in interesting ways, including using microshipments to reach dense urban areas, parachute airdrops to reach remote rural areas, or solar-powered watercraft to traverse inland waterways.

Innovation is not limited to the production and distribution of goods dedicated to rapidly emerging markets, because the products and their development will call for new approaches. The Internet will continue to expand as a portal for ascertaining market developments and trends. As indicated earlier in this chapter, the Internet more than any other mechanism serves as the great leveler in our global economy. Devising culturally distinct websites will be critical for providing a relevant and meaningful interface with customers for product development in emerging markets.

The 3-D printing technology mentioned earlier will support the rapid development of prototypes before it enters mainstream production service. The proposition of creating a tangible and functional mockup of a product concept in minutes will prove invaluable, especially as product variety grows to serve an increasing array of markets. Perhaps even more radical is the notion of developing product technologies and products that can adapt to different markets characterized by distinct cultures and local tastes. Products that reconfigure easily and operate differently based on the customer’s needs empower the manufacturer and customer to achieve the ultimate in flexibility. The question then becomes at what cost such capabilities are worthwhile.

Another supply chain process that will see the impact of global connectivity and socioeconomic leveling is returns management. Developing markets are often viewed as lacking sustainability awareness, but this is likely to change dramatically in the coming years. This is particularly true as people make the connection between the consumption of materials, energy, and water and the degradation of our physical environment, scarcity in natural resources, and quality of life. Customers in rapidly emerging markets will be quick studies in these dynamics. This will encourage companies to employ life cycle analysis, assuming greater responsibility for materials and goods throughout their life cycle. Companies also will try to have these materials and goods “reenter” the system for multiple life cycles (subsequent use through recycling, refurbishing, and/or repurposing). These firms will build reverse-logistics systems in emerging economies and exploit the benefits and profits of doing so. Since convenience is ordinarily a deciding factor in such systems, collection devices such as interactive kiosks and robotic collection vehicles will collect products and materials at the end of use. Such devices have been used for many years to collect used beverage containers in the United States where deposit systems exist. Their use is expected to expand, as will the ease and functionality of the collection devices.

The final supply chain process that will see the impact of the changing market environment espoused by emerging markets and improved global connectivity is the supplier relationship management process. Like CRM, SRM must race to try to understand the culture of operating in a foreign environment where norms can differ greatly from the home market. Much focus is directed at determining how to win over the hearts and minds of “choice” suppliers that can help the focal company navigate the treacherous waters of emerging market competition. Beyond identifying these select suppliers, we recommend making them a part of the success and rewarding them, in turn, for their contributions. In some cases, this might require formal strategic collaboration and even investing in suppliers that prove most instrumental in navigating emerging markets successfully. As with all the macrotrends presented in this book, we subscribe to the theory that supply chain management is a team effort. Companies that seek the expertise and engagement of the best suppliers and customers, respectively, will outperform firms that believe they can go it alone. This belief is more firmly reinforced in a world that is ever more flat and crowded. Hot? Well, we address that next.