2

The Learning Environment Design Processes

Learning environment design can be likened to landscaping. Beautiful gardens do not typically spring up fully formed, but instead are carefully planned and cultivated. The flowers themselves are naturally occurring somewhere, but the creation of a flourishing landscape in a particular place that suits the desires of the landowner often takes the talents of landscape architects and gardeners who select the best plants, design a pleasing arrangement, and create a supportive environment in which they can grow.

The same can be said of learning. Human beings learn all the time; it’s a natural process in many ways. But if we want learning to be cultivated, if we want to influence what is being learned, and if we want to nurture learning, then we need to shape the environment in which it occurs. Learning professionals create environments in which learning flourishes.

The learning environment design framework provides would-be learning gardeners with the tools to create rich environments for learning. Just like a gardener follows a process to cultivate a picture-perfect patch of earth, an L&D professional uses a flexible learning environment design process to support deep learning. Some gardening projects are not all that complicated, simply calling for quick purchase and planting. Others are botanical gardens with a large array of plantings and many hands to do the work; these become a transporting experience for those who enter. Learning projects are like that, too. While the same general processes apply, some are down-and-dirty, whereas others are rich and robust.

Learning environment design has five major processes that work together to create and continuously enrich an environment. Developing a learning environment is a lot like improving the landscaping around your home, in that it builds on what is already there. In assembling a learning environment, you are highlighting and shaping the available elements, while adding and juxtaposing additional elements that enrich the space and make it more useful.

At the center of your planning and thinking are the business goals and performance context from which the learning needs arise. It is critical that you first understand what the organization is trying to achieve, and how knowledge and skill will be put to use in day-to-day work. That context drives your purpose, and purpose centers your design efforts.

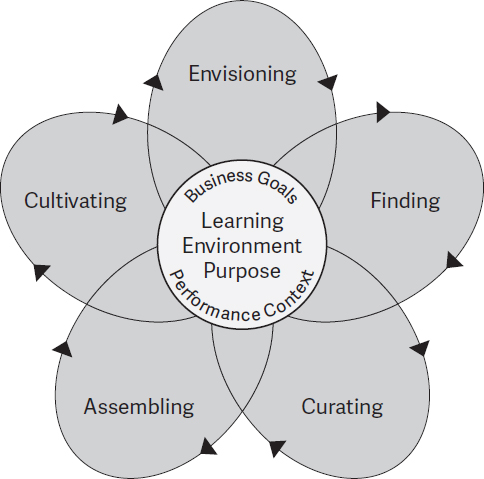

The processes for designing an environment are organic and iterative. The broad learning and performance ecosystem provides plenty of material to incorporate into a deliberately curated environment. The landscaping terminology used in this book and the daisy-shaped design graphic (Figure 2-1) capture the active dynamics of the overall learning environment design processes.

FIGURE 2-1. LEARNING ENVIRONMENT DESIGN PROCESSES

Designing a learning environment involves five overlapping processes, which we will discuss in depth in this chapter:

- Envisioning: Imagining the purpose, context, and components of the learning environment.

- Finding: Locating a range of resources and activities that are on topic.

- Curating: Using expert judgment to recommend the most relevant and useful components for the learning environment’s specific learners and purpose.

- Assembling: Collating and packaging the resources and activities, and making them available to your learners.

- Cultivating: Ensuring that the environment continues to be fresh, enticing, and useful.

Unlike the design of a learning event, a learning environment is never really complete; it is constantly evolving. You assemble a curated set of components for launch, and then continue to grow and shape them as the organization’s goals and the learners’ needs change and expand over time.

DRAFTING A LEARNING ENVIRONMENT BLUEPRINT

While in the process of designing a new learning environment, it is often useful to have a blueprint—a one- or two-page document that illustrates the overall vision for the package of resources you plan to collate. The document helps you to communicate your vision to learners and other stakeholders along the way, and it is easy to revise as you get feedback and suggestions.

In general, a learning environment blueprint contains the following information:

- Identification of the business goals and performance context that are shaping the need for a learning environment (determined in the envisioning process).

- A description of the purpose of the environment—what it is that you are trying to achieve (determined in the envisioning process).

- A description of the learners the environment is intended to support, including characteristics relevant to creating an environment for them—such as the number of learners, geographic dispersion, and access to and familiarity with computers and Internet (uncovered in the envisioning process).

- A description of the topic and scope of the environment—the knowledge or skill being learned and the intended depth of the resources (determined in the envisioning process).

- A list of learning components (put together in the finding and curating processes), organized in ways that make sense to the stakeholders.

- A sketch or prototype of the portal or package that will be used to make the environment available to the learners (a product of the assembling process).

- A plan for evolving and cultivating the environment—including strategies for learner-generated content and ongoing evaluation and maintenance (a starting place for the cultivating process).

When documenting a blueprint, take into consideration the needs of sponsors and stakeholders, crafting a short document that paints a picture that will inspire their imagination and address any concerns you anticipate. The elements of the blueprint should build on each other and serve as a framework for communication. The first four parts—business goals and performance context, purpose, learner description, and topic and scope—succinctly summarize the project so you can recruit people for finding and curating. Adding a list of components and conceptualizing how they need to be organized gives a solid vision to those who you may need to help you assemble or prototype the environment. Adding the sketch or prototype to your documentation puts you in a position to garner support for the additional resources that may be necessary to bring the environment to fruition. To cap off your blueprint, you may want to provide your stakeholders with a plan for ongoing care for the environment, such as recommendations for ownership, community managers, or site maintenance if applicable.

A complete blueprint is usually the product of an initial first run of all the design processes. Your needs assessment leads to envisioning, where you set the overall direction for what you want to achieve; finding and curating will give you a start list of components that you’d like to pull together. Finally, thinking through the assembling and cultivating processes will allow you to sketch your vision and assess the ongoing needs related to keeping the environment fresh. Keep in mind, though, that your blueprint has to remain flexible throughout the process; additional work on the project often leads to adjustments in details that were previously penciled in. See the appendix for three example blueprints.

ENVISIONING

Envisioning is imagining the purpose, context, and components of the learning environment. It is both a design step and an emergent process after the initial environment is launched.

Envisioning encapsulates these activities:

- determining the need for a learning environment

- defining the learning environment purpose and context

- getting to know the learners

- solidifying the topic and scope

- crafting a blueprint.

In one sense, envisioning is creating a complete blueprint for your environment so that you can share it with stakeholders for feedback and appropriate approvals. But at its core, envisioning is the process of defining a purpose for your learning environment; identifying the learners, topic, context, and limiting parameters that will help to shape and scope the environment you create. The core aspects of envisioning set the stage for all the other processes, which then feed the overall vision as the environment comes together.

Before envisioning—indeed, before even deciding that a learning environment is an appropriate strategy for your project—you will need to do some level of needs assessment. Using your toolkit of assessment techniques, you need to learn as much as you can about the project, the learners, and the learner’s needs. (A full discussion of needs assessment techniques is the subject of other books; a few of my favorite resources are referenced in the additional resources section.) If it’s not already part of your up-front assessment process, be sure to gather information about the business and performance goals related to the project. And, in addition to learner demographics and the information you gather to help define needs, you should explore how learners and related experts interact with one another and other facets of the learning culture.

Determining the Need for a Learning Environment

If your needs assessment shows that knowledge and skill development is necessary, you have a huge array of possible responses to address that need. Traditionally, learning professionals have selected one type of response: formal learning, in the form of a course, an e-learning module, or other structured component. But increasingly we have the kinds of complex learning needs that can’t be addressed by one solution. That’s when a learning environment makes the most sense. You need to use your judgment to determine whether the learners will benefit from having learning resources and activities compiled for their use.

How do you know when a curated learning environment would be a valuable way to support learners in developing their capabilities? There are a number of characteristics of learners, their environment, and the nature of the content that point to the need for a learning environment. Indicative characteristics include:

- The learning topic is a complex skill, requiring a deep knowledge base.

- The knowledge and skill is likely best developed over time through on-the-job experience and practice, even if some baseline training is also warranted.

- The knowledge and skill to be learned is more tacit than explicit.

- The knowledge and skill sets are constantly emerging.

- The learners’ needs with regard to the knowledge base or skill set are diverse, or the context in which they apply them varies.

- The learners are self-motivated and capable of managing their own learning.

- The learning culture supports experimentation and peer-to-peer learning.

In addition to asking questions that assess these factors, you might consider asking broad questions up front that can help you determine the degree to which a learning environment already exists for the learners. You could ask some of the following questions to gain information about each of the learning environment component areas:

- Learner Motivation and Self-Direction

o What are learners motivated to learn?

o How is their identity and success tied to ongoing learning?

o What hesitation or resistance to learning (if any) seems to exist?

o What is the cause of that hesitation?

o To what degree do learners manage their own learning?

- Resources

o What information and resources do performers use to support the learning needed to make them competent for performance?

o What is the technical environment for learners (degree of access to computers and the Internet)?

- People

o How are learners connected to one another and to experts in their field?

o What are the characteristics of the interpersonal environment and team environment for learners?

o What tools or processes are available to connect learners to other people who can support their leaning?

- Training and Education

o How do learners learn the foundation for their roles?

o What courses and programs exist to put learners on the right track?

- Development Practices

o What supervisory practices and company programs are in play that support or inhibit learning?

- Experiential Learning Practices

o What is the environment for learning by doing?

o To what degree are mistakes or failure tolerated?

o What practices promote reflection?

Defining Learning Environment Purpose and Context

A clear vision for a learning environment articulates what you want the environment to do to support learning and performance—its driving purpose and context.

Instructional designers are generally urged to write clear and measurable learning objectives for their projects, and to link them to on-the-job performance objectives and business goals. A learning environment, however, works differently from instruction. A learning environment plays a supporting role in helping learners meet self-defined learning objectives. To try to list all of those potential learning objectives as a foundation for learning environment design would be an impossible task.

Learning environment designers don’t specify what learners will know, value, or be able to do as a result of their encounter with the learning environment; the learners do that for themselves. Instead, they assemble a learning environment in anticipation of the emerging learning needs their targeted learners may have related to the given topic.

A few examples might clarify the distinction between instructional goals and learning environment goals, especially for those well-schooled in writing learning objectives for their projects.

Let’s say, for example, that you are designing a learning environment for salespeople, and part of your purpose is to help them to learn about competitor products. Consider how they might use that knowledge: Maybe they need to be able to write a detailed comparison chart for a client with particular priorities. Or, maybe they need to anticipate how products compare in general. If you were going to define learning objectives for training, you would realize that each application requires a different angle and level of detail. With a learning environment solution, you might conceptualize your purpose as connecting your learners to information—in this case, specific areas of competitor websites and industry review articles. You let the learners sort out what they need to learn in order to do their jobs effectively.

What if your project is to support woodworkers in improving their craft? The list of potential knowledge and skills that learners may want to develop is enormous. Some of those needs may be met by formal training in your environment, but the scope of learning support needed is much broader. Your purpose in designing a learning environment is to scaffold the ongoing development of skills and provide support for solving problems.

Or, your project may be to facilitate learning among people who are working in a leading-edge technical area. Learning objectives don’t make sense here because the learners have to learn through active experimentation and rapid iteration. The purpose of your learning environment might be to rapidly advance practice or to build a community of practice, both of which require a more active, learner-driven collection of resources, tools, and activities.

Remember that learning environments are a solution meant to enable self-directed learning, so the learners define their own goals. The learning environment purpose statement clarifies how you mean to support them in achieving their goals and guides your design decisions. Table 2-1 compares the goal-setting approaches used for instructional design and learning environment design.

TABLE 2-1: COMPARING INTEGRATED OBJECTIVES FOR INSTRUCTIONAL DESIGN AND DRIVING GOALS FOR LEARNING ENVIRONMENTS

| Integrated Objectives for Instructional Design | Driving Goals for Learning Environments |

| Business Objectives The business goal or initiative that your project supports. |

Business Goal The business goal or initiative that your project supports. |

| Performance Objectives The observable on-the-job behaviors that the program is intended to impact. |

Performance Context The on-the-job behaviors that are to be developed or affected by the learning environment. |

| Learning Objectives What learners will know, value, and be able to do at the conclusion of the training program. |

Purpose What the learning environment is intended to achieve, related to its topic and scope. |

Based on Hodges (2001).

The purpose is what the learning environment is intended to achieve, related to its topic and scope. Your purpose is driven by the performance context and business goals. Remember that in the design processes diagram (Figure 2-1), all three of these facets were depicted as the core around which the learning environment design pro-cesses revolve.

Typically, you identify the business goals and performance context before making the recommendation to design a learning environment, although these may need to be fine-tuned later on. Your environment’s purpose comes out of a thorough understanding of the overall context and learning needs.

The performance context defines on-the-job behaviors that are to be developed or affected by your learning environment. In some instances, you may be able to determine specific performance objectives that document what the learners should be able to do on the job (similar to instructional design), but that is not always the case because learners may be in different roles. The performance context provides an anchor and a top-level filter for finding and curating resources for the learning environment. Without a performance anchor, you might be tempted to include a lot of topical materials that would not be relevant or useful to learners.

There’s another reason that understanding performance context is an important up-front consideration. As part of your exploration of the performance context, you seek to ascertain the degree to which learning can affect performance. Often, when there is a performance issue of some kind, knowledge and skill gaps are not actually the most significant barriers to performance. If people are going to invest their time in deepening their knowledge or updating their skills, you need to be sure that those improvements are likely to result in solid, on-the-job performance. It’s possible that other performance interventions might have more impact, such as removing system constraints, aligning goals and incentives, or providing thorough feedback. A learning and development plan will only affect knowledge base and skill, and if these are not the most important contributors to performance or the reason for performance gaps, then devote your time and energies elsewhere. A full discussion of this kind of performance consulting is outside the scope of this book, but a short list of recommended resources on this topic is included in the additional resources section.

Another important contextualizing factor is understanding the business goals that require the capabilities your learning environment supports. Business goals justify the energy required to design and cultivate a learning environment by generating the performance objectives and the human capability required for that performance (some of which may need to be learned). It may be more difficult to identify the specific business goals being supported if your learner group comes from differing companies, departments, or contexts. But it is worth the effort to explore or hypothesize the kinds of business goals that might be affected in order to create a relevant learning environment.

With the business goals and performance context in mind, you should be able to define your learning environment’s purpose. The purpose statement usually begins with an action verb—what you want the environment to do for the learners. You’ll be able to evaluate the achievement of that purpose by surveying the learners or looking for a change in learner capability or learner performance outcomes.

You should articulate the purpose of your learning environment specifically for your situation, but we discussed a number of possible purpose statements earlier (see Table 1-1), which you may be able to leverage. Here are some of those examples:

- Support exchange of explicit knowledge.

- Provide ongoing support for developing routine skills.

- Support the exchange of tacit knowledge.

- Improve craftsmanship; support building of deep skills.

- Support application (performance).

- Capture and spread new knowledge.

- Provide support for solving problems.

- Nurture a community of practice.

Write a clear purpose statement in your own words, stating what you and the learners want to achieve with this environment. It isn’t necessarily important to determine which strategy— blended learning hub, knowledge exchange, learning resource portal, or collaboratory—matches your particular project because they often overlap. However, keeping a particular strategy in mind can provide helpful shorthand for what you are trying to achieve.

Getting to Know the Learners

The learner group is usually defined by job role or by identifying people who do a specific kind of task. You identified the learner group when you defined the project, but it’s useful to deepen your understanding of the people who will access the environment as you start to envision the details. To aid your decisions about curating and assembling it is helpful to know how many learners you have, their geographic dispersion, their familiarity with one another, their access to and familiarity with computers and the Internet, and the typical turnover the group may have. Getting more details about their job roles, current performance, challenges, and learning preferences will also help you make better curation decisions.

In later chapters, we will discuss how important self-direction and social learning are to the success of a learning environment. As you explore the characteristics of your learner group, be sure to assess their degree of motivation for learning in the defined arena and the skills they have for managing their own learning. You’ll want to identify the kinds of support the environment may need to provide to promote motivation and self-direction. Additionally, you’ll need a high-level assessment of the learners’ current social learning practices and their readiness to engage with one another and others to support their own learning. It may be important to know how friendly and supportive the work environment is, as well as how much trust and mutual learning is already a part of the group’s make up. (See the self-directed learning pillar strength assessment in chapter 3 and the social learning readiness assessment in chapter 4 for additional ideas on what to explore in these areas.)

And of course, you want to develop a more nuanced understanding of the target group’s learning needs in relation to the topic. You need to know the degree and nature of their baseline knowledge and skills. Your needs assessment should explore how the learners define their learning needs, as well as their preferences for modes, tools, and techniques for learning.

Solidifying the Topic and Scope

To have a manageable focus for the environment, you have to balance the breadth you cover and the number of contexts in which the learning will be applied. Your decisions here often influence how you envision your core learner group.

You can imagine, for example, that learners in any topic area could have novice, intermediate, or advanced levels of knowledge and skill. If the topic is narrow enough, you may be able to support development at all levels and serve a wide range of people. But it’s also possible to focus your attention only on the newcomers, or only on the advanced level practitioners.

Another way of refining topic scope is to consider the context in which your learners will be applying their new knowledge and skills. Because learning is best promoted when it is contextualized, a variety of contexts may increase the scope of what you need to include. Some variability among application contexts is inevitable, of course, but you may need the group to have enough in common that you are not trying to create multiple streams of resources for learners who are in very different contexts.

For example, you might be building an environment that supports the development of presentation skills. It may be reasonable to envision supporting learning from novice to expert; however, it will be difficult to serve all the needs for people who do sales presentations and people who report project results and people who do keynote presentations in a large venue. Each of these contexts suggests different knowledge and skill needs, and therefore different resources.

Or consider the possibility of building an environment to support writing skills. Depending on your target audience, you may choose to focus only on writing in an academic context (perhaps writing for an academic publication), writing marketing materials, or writing for online publication. Narrowing the focus helps you to have a more reasonable scope. You may also want to narrow the level of writing skills you tackle—deciding, for example, that the environment won’t aim to serve those who need help with core grammar skills.

Crafting a Blueprint

You may have noticed that identifying purpose, learner group, context, and so on is not a series of linear steps. Making these decisions is a balancing act that requires an understanding of the impact of each decision on the others. For example, knowing the learner group you want to serve can help you make decisions about topic and scope. On another project, further analysis of the business goals you are trying to support may push you to expand your learner group. There is no one right way to go about finding the right balance, but the business goals and performance context can help anchor your decisions.

Often, creating a blueprint is a two-step process. In the first step, you document the business goals and performance context, your purpose, a description of your learners, and your topic and scope. In the second step, you use your emerging blueprint to enter into additional processes: to find and curate components, and sketch out how they might be assembled. As your vision comes together, you can develop a longer-term plan for cultivating and evolving the environment over time.

FINDING

Finding is locating a range of resources and activities that are on topic. It involves gathering ideas from subject matter experts and learners as well as conducting a search for resources available on the web.

Finding encapsulates these activities:

- gathering current resources

- researching additional resources

- encouraging learners to contribute.

Finding the resources to recommend to your learners is an important part of learning environment design. Learners will almost always attempt to find resources to support their own learning, but this can be an inefficient and frustrating process, especially now that the web offers so many options. Your role is to find valuable, on-point resources; that means finding and curating from a lot of options. The learning environment components chart (see Figure 1-1) is a useful guide to searching for a variety of components.

Gathering Current Resources

Start with the learners and senior people familiar with the knowledge base and skill you are trying to support. Ask them to share any resources they have found useful. (See the suggested focus group agenda sidebar.) Use a blank components chart (or another organization scheme) to capture the results of this initial research. You could also use your time with learners and subject matter experts to explore any areas for which they have been unable to find relevant resources (topics or types) so you can concentrate your energy there.

A Focus Group Method for Gathering Learners’ Suggestions for a Learning Environment

One effective method for gathering information about what’s already there is to facilitate a focus group. Bring together a small group of learners to discuss how they learn the knowledge and skills you are targeting. Use the components chart as a guide to ask pointed questions to draw out what’s available, how effective it is, and what’s missing.

The process might look like this:

- Focus. Get the focus group participants to focus on the topic at hand, lay out the knowledge and skills you are targeting, and perhaps generate a short discussion to clarify them.

- Free write. Ask participants to free write (on individual sticky notes) all the resources they use to support their own learning in these areas.

- Document. While they are writing, post component category labels around the room. These could be “resources, people, formal training and education, development practices, experiential learning practices,” or they could be categories of your own devising. When participants are finished, briefly explain the categories and ask them to post their ideas in the relevant areas. Provide a handout of the component list to prompt further thought. They can continue to write down any ideas and post them as they come to mind.

- Discuss. Now that a collection of resources is on the wall, facilitate a discussion that gets at the following points:

- Clarify any items that were posted.

- Determine the perception of those items’ effectiveness.

- Identify additional resources in each category that participants would find useful.

- Get recommendations about the kinds of new resources that are most important.

Researching Additional Resources

Once you have explored what learners and tenured employees can share with you, it’s time to do some additional research on your own to see what you can add of value. Better still, you could engage a small team of people to help you find the best resources, especially if your command of the topic at hand is limited. Senior practitioners or managers may have a better idea of where to look for resources and which search terms are helpful.

You’ll need to put all your Internet search skills to use. Look across all the component categories to find resources in as many as possible. The materials don’t need to be evenly distributed, but it is important to have a variety. Here are a few places to start:

- Browse the websites of the professional organizations or journals that serve your learners. Consider posting questions about resources if they have a forum you can use.

- Review conference agendas and industry articles to identify thought leaders, experts, and vendors that are relevant to your learners. Look for ways to connect with these people, resources they have published, or formal learning events they run.

- Review the Twitter streams of thought leaders in the field and explore the nature and source of the resources they are sharing. You may also find additional people you can recommend that your learners follow by examining whom these thought leaders follow.

- Search for any vendors, colleges, or universities that serve your learners; they may have resources or links available on their websites, as well as education programs you could recommend.

- Search for articles and blogs to find people who are writing on your topic area; they may have additional helpful content that you can recommend to your learners.

- Go to Diigo, Delicious, or other public bookmarking sites and find out what people have tagged with keywords in your topic.

- Take your list of potential components to internal and industry leaders; see if reviewing your partial list prompts additional ideas.

Consider asking multiple people to conduct some of these searches. Because search engines and social media aggregators use your history to try to ensure you get relevant content at the top of your search results, different people will get different results (sometimes vastly different results).

Once you know the learners’ perceptions about possible learning resources and the usefulness of the materials they mention, you should also do your own evaluation of their quality and effectiveness (see the section on curating in this chapter). Part of the role of curation is to select the most high-quality resources.

Encouraging Learners to Contribute

A learning environment can be made all the richer with the active involvement of the learners themselves. As learners find additional resources they want to recommend to their peers, they should be able to contribute those items, either directly (recommended) or through a vetting process (if necessary). Some of the richest learning environments encourage the learner group to create resources that teach their peers. Providing the software (screen capture or video-making software) or tools (internal blogging or messaging) is one way to encourage learner-generated content.

A big concern of many learning environment sponsors and owners is ensuring that the resources are accurate and of high quality. You could put a process in place that requires all new additions to be vetted (before or soon after being made available), which may be required in a regulated environment. Another strategy is to allow learners to rate the materials or flag materials that are inaccurate, inappropriate, or otherwise not useful.

To learning professionals who pride themselves on the quality and accuracy of their work, giving carte blanche to add resources that have not been proofread or fact-checked may be disturbing. But many who have allowed it (Wikipedia among the most famous) have learned that inaccurate materials are usually quickly identified, either by experts monitoring additions or learners who recognize mistakes. Most people who contribute aim to share good-quality materials. If issues do appear, it’s better that they become known in the organization rather than going unrecognized.

Allowing learners to contribute in these ways makes creating and maintaining a curated list of resources much more efficient, which is a nice advantage. Again, determining if and how learners may contribute to the curated list is a judgment call, and there is no one right answer. Still, erring on the side of making the environment as open as possible is recommended because it communicates a degree of trust and respect that is a good message to employees.

CURATING

Curating is using expert judgment to recommend the most relevant and useful components for the learning environment’s specific learners and purpose.

Curating encapsulates these activities:

- filtering

- categorizing and tagging

- adding value by contextualizing and highlighting

- making connections and generating discussion.

There is a big difference between aggregation and curation! The curation process requires you to select the best resources among all the possibilities you gathered in the finding process. Curators add value when they perform the following actions:

- Find material to keep the collection fresh.

- Filter material using human judgment to identify what is relevant and valuable.

- Categorize and tag to make the right material easy to find.

- Contextualize and add commentary to enrich the impact of the collection.

- Highlight trends and bigger-picture stories to enable sense making.

- Make connections between related (and seemingly unrelated) materials to provide deeper insight (often through initiating discussions).

- Generate discussion among people to create a community and enable knowledge and skill creation.

As you can see from this list of actions, the learning strategist or learning environment leader does much more than simply provide a lot of links. Without the organizing structure, contextualization, and enrichment provided by highlighting, connecting, and enabling discussion, your collection is just one step removed from an Internet search.

Filtering

Harold Rheingold (2012) calls the filtering process “crap detection” and it’s a good idea to be skeptical. Your skepticism should extend to any resource or activity you find, not just those on the Internet. There are a few things we can do to filter the materials we find: validate sources, sanity-check using your own expertise, quality-check the materials, and check for copyright.

VALIDATE SOURCES

We all know that anyone can put anything up on the Internet, but there is something about a professional-looking webpage and the solidity of published materials that lessens our inclination to doubt. Depending on your level of concern, there are many strategies that can be used to validate the source of what you are finding. Here are the basics:

- About: Check the “about” section or biographies for the relevant credentials of the information’s source. You may also want to validate that information through other sources (for example, by checking LinkedIn or employer sites for corroboration). If there isn’t an “about” section, backtracking the URL to the primary webpage may give you an indication of the authors.

- Links: Check whether credible referrers are linking to a site by searching “link: URL” to see who links to that page (and what they say about it).

- Investigate the source: Search for the people and organizations referenced in the material, and look for any news articles, endorsements, or critiques.

- Check for currency: Look for copyright dates. If you’re looking at a webpage, check to see when the page was posted or last edited. If the content cites other articles or books, what is the most recent date on the list of references? If the topic is evolving, outdated material won’t be your best source.

SANITY-CHECK USING YOUR OWN EXPERTISE

Expertise is the primary tool curators use for validating potential resources. If you are not an expert in what you are curating, it is important to recruit a good advisory board or trusted subject matter expert to serve that role. Triangulation (multiple search strategies) or saturation (keep looking until searches start giving results you already have) are also good practices to put into play here—look to see if multiple sources say similar things, and then pick the best one or two in your opinion.

QUALITY-CHECK THE MATERIALS

Consider whether the material meets the standards for quality that your learners expect. Linking to poorly designed websites, clumsily produced videos, or grammatically incorrect articles will call into question the accuracy of the material, as well as the carefulness of your curation. A small lack of production quality is acceptable when the material is otherwise above grade; for example, many great tutorials are produced using smartphone cameras, without fancy lighting or subtitling. Evaluate all aspects of a piece before making a decision. Your quality check may also lead you to recommend revisions to materials that are already available to learners (such as enhancements to your internal database).

All materials should be accurate, timely, engaging, and relevant to the learner’s context. Here is some additional advice for checking the quality of different categories of components.

- Resources: While they don’t need to be perfect, they should be of solid production quality (well-written, clear video and audio, easy to follow). If a resource is a link to a database, that database should be accessible, searchable, and well-categorized; it is often helpful that they be annotated in some way.

- People: If you recommend social media connections (blogs and Twitter feeds), look for active accounts with regular posts that are likely to be relevant to learners. Discussion boards should be frequently monitored and easy to filter. (Also check to see if they often post materials not appropriate for work.)

- Training and education: Vet training and education recommendations for adherence to endorsed practices and adult learning principles. If possible, include a variety of delivery modes to meet varying learner preferences.

- Development practices: High-quality practices are relatively easy to implement and consistent over time.

- Experiential learning practices: Tools for self-assessment or suggested reflection questions and exercises should be clear and validated (if possible). Related recommendations for next steps should also be available.

CHECK FOR COPYRIGHT

Check the copyright information or website terms of use for the requirements related to linking to materials or copying them to your own servers. Sometimes, copyright owners request that you link to a webpage, rather than linking directly to a PDF that is on the site. Most people do not allow you to copy their content to your site without permission (which can be free). Some companies may have internal guidelines related to linking to web content, so be sure to check with the appropriate colleagues for additional limits if that is the case.

Filtering is an early step in the curation process, and a valuable one. Once you’ve validated, sanity-checked, and quality-checked the components you have found (and ensured you have permission to link to them), your list may be somewhat whittled down and you’ll be able to make your final selections on what to include in the learning environment. Learners count on you to cut through the noise and find the most useful materials to support their learning. If they find that the material is inaccurate, outdated, or relatively useless, they’ll go back to using their own search methodologies for finding materials, and your attempts to support them will be for naught.

The question is, by what mechanism does the cream rise to the top? The secret ingredient is people. In order to collect the best content and put it together, someone’s got to figure out what’s best. That’s what curators do; they bring their judgment and experience and taste to bear on the question of what you and I should look at next. And we cannot survive without them.

—Steven Rosenbaum, Curation Nation

Categorizing and Tagging

The curating tasks of categorizing and tagging actually have their biggest impact on the assembling process—when you pull the resources together in some kind of package for the learners. The longer the list of resources, the more important it is that it can be browsed and searched using keywords and categories. Your platform will determine how this looks to your learners, but defining the actual category and keyword terms is an important decision for the curator to make.

In documenting your component list, use ways of categorizing the components that will make sense to the learners and the stakeholders, rather than the component categories. The component categories in the learning environment design framework are useful guidelines from a design perspective, but you’ll probably want to use a more customized scheme for communicating to your stakeholders.

Often, the most useful categorization takes into consideration what the learner wants to be able to do, because people search the environment to support their tasks or projects. Using categories that align with the work flow or are action verbs helps learners quickly find what they need. Or, the knowledge base and skill set you are covering may inherently have a topic-specific categorization scheme that learners will understand. Tagging things in multiple categories can also support ease of use (such as by process step and type of resource).

In their work with collating performance support assets, Conrad Gottfredson and Bob Mosher (2011) describe four different kinds of categorization schemes you could consider:

- workflow context: organized by process step

- job role context: organized by who is accountable

- task context: organized by association with specific things to do

- custom context: organized by categories specific to the project.

When considering how to categorize and sort materials, be sure to talk with your learners and gain their perspective. Experts in the topic area may also provide important insights to this part of the process. Where possible, it can be very useful to use “folksonomies”—that is, to allow the learners to tag content in ways that are meaningful to them (or to help name the categories you will use).

The act of categorizing and tagging often reveals weak areas in your learning environment; you’ll discover that you may have too much of one category and not enough in another. Your curation process can therefore send you back into finding mode as you seek to deepen those areas you missed in the first round.

Contextualizing and Highlighting

The problem with search results and lists of links is that they often don’t give any explanation of why certain things are useful or how to apply the material to your work. Thus, where possible, it can be quite helpful for the designer or curator to point out important material or applications. This can be done using brief descriptions or through clues on the site where the materials are accessed (for example, by featuring content or making its context explicit). While this is only a small aspect of curating, anyone who has tried to find something from an Internet search result will tell you that helping people understand the significance of an item before they click on it is very helpful. The same is true when your materials are in physical space—a wall of books is a daunting sight, but there are many ways to highlight resources for specific purposes.

Making Connections and Generating Discussion

Making connections and generating discussion are advanced functions of the curator role, which especially come into play when the learner group is developing new knowledge or practices. The role isn’t played by just one person; instead, any member of the group can point out how ideas connect and get people talking about problems and ideas.

You’ll see connections being discussed on blogs associated with the learning environment or on discussion boards. Most importantly, this kind of curation add-on happens in hallway conversations and over lunches—whenever people get together to talk about their work. The learners point each other to additional resources and add in new ideas they’ve discovered.

Our role as learning environment designers is to ensure that the environment is conducive to these conversations, whether they are happening electronically or in person. See chapter 4 for more on building a learning community.

ASSEMBLING

Assembling is collating and packaging the resources and activities and making them available to your learners.

It encapsulates the following activities:

- determining how learners will access the environment

- incorporating learner-friendly functionality

- envisioning the look and feel

- opening the gates.

Imagine that you have done your research and gathered helpful Internet links, database links, and articles; identified the thought leaders on the topic; vetted conference options; identified courses that might be useful; collated some helpful on-the-job practices; strategized a discussion forum and learner-generated content approach; and more. You have all this curated stuff; where does it go? How do you provide access to these resources and activities?

Determining How Learners Will Access the Environment

Most often, learners access the environment through an electronic portal of some kind. A portal can act as a metaphorical gate to your garden of resources. The trick is to design a portal that is intuitive and flexible. There are a number of tools that promise that capability, including SharePoint, Yammer, Jive, SocialCast, and Canvas. These possibilities all have their limits in terms of ease of use, customizability, and capacities, but—unless you have the capability to design your own portal—they provide the starting point for collating resources and providing an entryway to curated content.

A portal is a great organizing solution for links, resources, and discussion boards, but perhaps less so for accessing people, development practices, and learning by doing. Still, an expert directory, articles or resources for establishing development practices, and advice on improving your on-the-job learning can be useful. Even resources on learning to learn can be highly valuable, and can be included on a portal.

It’s possible that creating a portal doesn’t really make sense, perhaps because your learners are using tools that are difficult to collate, or the components just don’t need to be organized in one entry point. Some projects can be “assembled” by simply providing a short job aid that provides links and guidance for learners to set up their own personal learning environments. And if a one-stop portal isn’t possible in your organization because of regulatory, budgetary, or system constraints, an old-fashioned resource handbook can work just fine.

Incorporating Learner-Friendly Functionality

Whatever you create, you want to check that you’ve met ease-of-use criteria to make sure it is inviting to learners. The learning environment should have some of the following characteristics, given the purpose, type, and platform of your environment:

- Easily accessed in the normal flow of work: The environment should be accessible to learners at the point of need.

- Searchable: Learners need to be able to quickly locate what they need.

- Intuitively organized: The organization scheme should use categories and tags that learners recognize.

- Up-to-date: Outdated material should be removed regularly.

- Annotated: Each item should contain a brief description to help learners know if it’s what they’re looking for before they get too deep.

- Tagable: Where possible, allow learners to tag or save their favorite resources.

- Rateable: Learners should be able to highlight the most useful resources for their peers (and identify questionable resources for learning environment leaders).

- Open: Learners and experts should have some mechanism to contribute resources and activities to the environment.

- Visually appealing: The site should convey energy and appear uncluttered, organized, and modern.

If the nature of your learning environment doesn’t incorporate an online portal, some of these ease-of-use criteria can still be applied. Any documentation still needs to be easily accessed, searchable, intuitively organized, up-to-date, and annotated to some degree.

Envisioning the Look and Feel

However you communicate your learning environment to your learners, it should have a look and feel that conveys value, credibility, energy, and ease of use. As you get ready to assemble the environment, determine a visual and graphic design that is professional and appealing. Don’t underestimate the importance of the visual design of the documents or webpages you use to provide access to materials; similarly, don’t underestimate the importance of the comfort and decorating scheme of physical environments.

Visual cues help learners feel confident and excited about using the learning environment. Anyone with experience using computers has an appreciation of the way that user interface design can support the use of a system or make it frustrating and time-consuming.

Research has now proven that multimedia and interface design affects how users learn. The myth of visual design as an optional extra (which is alive in too many dark corners) is in desperate need of busting. The hard fact is that how you create graphics, sequence interaction, display information, use animation, and design for social presence and emotion will impact how users learn. This is interface design.

—Dorian Peters, Interface Design for Learning

At a high level, you’ll need to pay attention to the use of graphics and animation, as well as colors, typefaces, and layout. Equally important are your decisions about information design and architecture: the structure of the site, labels used, and navigation.

Dorian Peters has written a well-researched book, Interface Design for Learning, which is a fantastic manual for the nuances of creating an effective look and feel for your learning environment. Another great resource is Connie Malamed’s Visual Design Solutions. In many organizations, you will collaborate with other experts in information technology or web design, but interface and visual design for learning have additional requirements based on learning theory concepts, such as cognitive load and scaffolding.

Opening the Gates

Once the learning environment is assembled, it’s time to open the gates and invite the learners in. When launching an environment, it’s often helpful to have a full-scale publicity campaign and some special events that call attention to the resources available. Here are some of the ways that you can actively invite your learners to take advantage of (and contribute to) the environment:

- Publicize the learning environment through some of the same channels you publicize your formal learning events (email, web banners).

- Arrange demonstrations for learners, which could take the form of a table in the lunchroom, a video on the homepage, or a presentation at a staff meeting.

- Invite supervisors and informal leaders to be advocates for the environment.

- Begin compelling conversations on the environment’s discussion boards or social media streams to demonstrate the value of asynchronous exchanges on topics of interest.

- If you have options for learners to contribute, host “seeding” events that ask people to contribute resources for specific subtopics or resources of a particular type.

- Share wins from the social interaction aspects of your learning environment to show examples that others might imitate.

- When new people come on board, be sure to formally orient them to the learning environment. New hire training programs should use the learning environment as much as possible to demonstrate to learners how to find resources and support their ongoing development.

In a world full of distractions and new tools, it’s never enough to simply publicize the opening of your environment. Your cultivation plan should include ongoing communication and intermittent publicity efforts. Once the learners fully engage with the environment and make it their own, you may be able to pull back, but you can boost learners’ efforts with continued promotion. Consider regularly repeating some of the strategies you employed to launch the environment. Of course, the most impactful publicity is always word-of-mouth, and the more your learners find ongoing value and support in the learning environment, the more they will engage with it, contribute to it, and tell their peers about it.

CULTIVATING

Cultivating is the process of ensuring that the environment continues to be fresh, enticing, and useful, which requires the infusion of new material, pruning of outdated resources, and ongoing evaluation of what’s working and not working.

Cultivating encapsulates the following activities:

- establishing leadership for the environment

- expanding and improving the environment over time

- nurturing a learning community

- pruning and keeping the environment fresh

- evaluating the learning environment.

Any gardener will assure you that planting is just the beginning of an ongoing cultivation process as the garden evolves. The same is true of a learning environment.

A vibrant environment lives and breathes, and you have to plan for how it is going to grow and the roles and resources needed to keep it flourishing. Instituting an annual or semiannual comprehensive review would be a good practice, because it ensures some concerted attention on cultivating the environment on a regular basis. (Some projects might even justify a quarterly review if the topic is evolving rapidly.)

Just like a beautiful garden choked with weeds, an untended learning environment stops being useful, and all the work you did in assembling and promoting it will have been wasted.

Establishing Leadership for the Environment

One of your most important tasks is to establish leadership of the environment by some invested party: a steering committee, management team, or senior practitioner. You should do this early in the learning environment design process, while you are still finding and curating potential resources. Leaders must value the environment and understand the current work context, as well as the emerging knowledge and skill development needs.

The role of leaders is to continuously oversee the environment and ensure that it is achieving its purpose. They may vet additional materials and activities that are added, serve as social media authors (for blogs and Twitter feeds), act as advocates in the workplace, commit to responding to discussion board questions, and so on. They may also identify and commission new resources to meet emerging needs. In the most active environments, the leadership role is often taken over by the learners themselves. Nonetheless, designating someone to keep an eye on the activity and outcomes is wise.

It is important to communicate that ongoing evaluation, maintenance, and enhancement activities will need to be supported over time. Estimate the amount of time that may be necessary—this will depend on the nature of the environment and the role you have assigned to leaders—and make sure that leaders have enough time to do the work. This time must also be protected; otherwise newer projects or pressing deadlines will cause needed cultivation to fall by the wayside. Consider having leaders track their time so you can better manage it. You may also need to develop high-level plans for learner-generated content and its ongoing cultivation in order to give your stakeholders a realistic view of what this part of the process will entail. These plans are often part of the learning environment blueprint.

Expanding and Improving the Environment Over Time

The leaders and designers of the environment should continue to actively identify new resources. They should also monitor the knowledge and skill base of the learners, as well as their performance demands and business goals, so that evolving needs can be addressed. The owners and designers can support ongoing learning through exemplary curation practices—especially by highlighting, making connections, and generating relevant discussions in order to make the environment an active learning resource center.

An important mechanism for cultivating a learning environment is the involvement of the learners themselves. Many environments incorporate a strategy for learner-generated content, by which the learners can suggest or add resources to the mix. Some organizations provide tools for people to create their own resources (such as short videos or screencasts) so that they can share their knowledge and skills with one another. There are potential drawbacks to this method; with many contributors, each with their own way of thinking about the subject, it’s easy for your “curated” materials to grow into a mountain of resources in which it is impossible to find what you need.

Nurturing a Learning Community

Promoting interaction among learners and between learners and experts is often at the heart of a learning environment, and it usually requires more effort than just opening up social spaces. Tactics for nurturing a community are discussed in chapter 4 and you’ll find many specific considerations and ideas on those pages. At a high level, nurturing a learning community involves facilitating engagement among members, prompting contributions to the site through learner-generated content or participation in discussions, ensuring timely responses, inviting experts to engage, promoting successes, deliberately starting interesting conversations, addressing emerging needs, moderating experience, cultivating support for the environment, and reporting on results and outcomes.

Some environments may need little intervention to promote interaction, whereas others may need some help to get started. You can’t make people engage (and you shouldn’t require it); your role is to make the environment so useful and enticing that people willingly leverage it for their own learning.

Pruning and Keeping the Environment Fresh

While the environment grows, it’s also critical that you weed out any resources that become outdated or prove to be unpopular with learners.

This, again, is where the curator role comes in. A curator must be a tough critic and a ruthless pruner, making some materials unavailable so that the best can stand out. Don’t underestimate how important this part of the curating role is; your intent is to provide a narrower set of options that have been well vetted, not to duplicate what can be found through a search engine. Very little actually gets thrown away, but learners who want more obscure resources may need to go into an archives section to find what they are looking for.

To guide pruning, environments can enable rating systems or comments and suggestions that allow learners to identify the best resources and those that are not particularly helpful. Some resources may be tagged with expiration dates so they are automatically removed or sent for review.

An important consideration while you are curating and pruning is attending to the diversity of the available materials. Curating materials means you are narrowing your learners’ fields of vision, but it is also important to have diversity of thought and resources in order to support deeper thinking and innovative application. Giving learners multiple approaches to a skill or several articles on a particular point increases the likelihood that they will find relatable material. Hiving diverse content is a delicate balancing act because you don’t want to confuse learners with too many options and approaches. Being transparent in the decisions you make can help stakeholders weigh in if needed.

Evaluating the Learning Environment

In the age of big data it is important to determine which data will serve you well in ensuring that the environment effectively supports the intended knowledge and skill development. The key questions you want to ask are:

- To what degree is the learning environment fulfilling its purpose?

- To what degree are learners able to find what they need to support their own learning and development goals? (What’s missing? What is hard to find?)

- Which resources are most useful, and which need to be removed?

- To what degree are learners improving in their knowledge, skill, and capability on the job in the targeted areas? To what degree is the learning environment supportive of this improvement?

- To what degree is growing capability in the targeted knowledge or skill area evident in the performance of the learners on the job?

The most valuable data help you continue to make decisions to keep the environment active and fresh. Computer-based systems often provide access data (how many people have clicked on a resource) and other indicators of use, but these data aren’t necessarily indicative of the content’s quality or usefulness, and are not recommended for decision making (see the first column of Table 2-2). More helpful data are those that indicate how useful the resources are (as rated by users). If you can enable a rating system of some kind, that data will make it more efficient to identify components that need improvement or pruning.

You may also have formal quality evaluation strategies for some of your components (for example, course evaluation practices and feedback forms). Informal observation data could also be gathered from development practices and what managers can see of experiential learning practices. These data points help to evaluate specific components, but not the learning environment as a whole.

Table 2-2 illustrates further ways to evaluate the learning environment.

TABLE 2-2. POTENTIAL LEARNING ENVIRONMENT MEASURES

| Activity | Value | Impact |

(Not recommended for decision making)

|

|

|

The most efficient and credible approaches to evaluating learning environments as a whole are survey and focus group data. Short surveys can be sent to entire learning groups and their managers to gather data on the questions outlined. Focus groups can provide richer perspectives and more nuanced feedback. These strategies can be accomplished efficiently and will aid in decision making about the learning environment strategy.

It is also critically important to keep your eye on the reason the learning environment was called for in the first place—the business and performance goals that required the capability being developed. Even if people rave about your environment, you still need to monitor the business and performance indicators. If they are not where they need to be, you’ll want to analyze whether the environment is addressing the right needs, or if there are other learning-related or performance environment problems that need to be tackled. While we may want to bask in strong evaluations from learners, we (and many of our stakeholders) are more interested in evaluating the outcomes.

PROJECT MANAGEMENT

Managing the design and development of a learning environment is often a multifaceted task, and it’s useful to think of it like a software product (version 1, 1.1, 1.2, and so forth) rather than as a defined project that will be closed out immediately after launch. There will no doubt be iterations, additions, and occasional fixes, even after the environment has been made available to your learners.

In addition to managing the ongoing development of the environment, you may also launch specific custom design, development, and implementation projects. Perhaps you determine that you need a database that doesn’t yet exist, or that existing training needs some additional modules. Your ongoing plan may also include a regularly published blog, newsletters, or Twitter feed, and you might need to manage authors and posting schedules.

Your overall process could also involve prioritizing what needs to be created or revised, and launching separate design projects for these components. Your envisioning and project management skills will come into play as you think of the full scope of the environment you plan to craft, while juggling all the tasks needed to complete desired components.

At some point, you will have enough material in place to launch, even if you are still building or researching some components. Don’t let a lack of some resources keep you from doing this. Learning environment design is a long-term effort; a project that is never “done.” Go ahead and launch the environment as a work-in-progress, so long as there is some obvious value to what you already have. The more you can demonstrate the value of the environment for the learners and for the accomplishment of business goals and initiatives, the more support you will have for developing additional components.

Ongoing management also includes additional curation, regular pruning, evaluation, and ongoing communication. These tasks are part of the management of the environment. For some environments, these tasks will be relatively easy, whereas others may need a near full-time manager or a small team of owners to oversee these processes and build community. Every project will have its own requirements and challenges, and you would be wise to bring your project management skills to the table along with your ability to envision the possibilities that a learning environment strategy will enable.

HIGH-LEVEL ENVIRONMENT QUALITY CHECK

There are no hard-and-fast rules about creating a “perfect” arrangement of resources and activities. Just as a gardener is constantly acquiring new plantings and exhibiting them in different configurations, a learning environment designer or owner is always actively curating the collection. These processes are recurring constantly or regularly in order to keep up with the changing needs of learners and emerging knowledge and skill advances in their fields.

Nonetheless, there are some broad quality checks you can apply to your environment-in-progress to assess its likelihood to be useful.

- Validate that you have the materials that will help you achieve your purpose. Put yourself in the learners’ shoes and imagine what you would need to embark on self-directed development in their contexts. (Or work with a subgroup of learners to validate your recommendations.)

- Ensure that there are resources across all component categories, although it is not necessary to have an equal number in each. In some instances you may have little control over development practices; in those cases, you might consider adding a set of resources to help managers establish development practices within their organizations or teams.

- Verify that the environment has elements that promote learner motivation and self-direction. This characteristic of your environment is usually supported by materials in every category.

- Review resources and activities with an eye toward the degree of learner engagement they promote. Are there plenty of components that can be described as enticing, interesting, challenging, provocative, hands-on, or interactive?

- Be sure you have elements that promote learning by doing. Most importantly, ensure that the environment supports experimentation, feedback, and reflection.

- Consider Conrad Gottfredson and Bob Mosher’s “five moments of need”—the idea that employees need support on five broad occasions: when they want to learn for the first time, when they want to expand or enrich their learning in an arena, when they apply their learning, when things change, and when things go wrong (2011). Imagine your learners in any of these situations and see if you have resources that would help.

You can do additional quality checks at the component level. This chapter contained specific recommendations about filtering and curating materials that should prove useful; in addition, you may have your own criteria.

The job of curating an environment is a big one, and it is important to underscore how vital it is to continue to curate on an ongoing basis. Learning environment design is not a once-and-done project; it requires consistent attention from people who are vested in continuing to support the learners in their development.

PRINCIPLES OF LEARNING ENVIRONMENT DESIGN

Learning environment design is often very emergent, being put together over time by those committed to supporting development—whether designers, learning leaders, or learners themselves. There is no one right way of designing a learning environment, but there are some essential principles that can provide broad guidance to whatever activities take place to curate and assemble an environment. The following are some essential principles for designing learning environments:

- Empower and trust learners: Assume that learners are capable of identifying their own needs and following through to learn and apply (even if you need to provide some initial scaffolding for their efforts). If you try to encourage activity by requiring participation, you’ll likely cause more harm than good to your learning environment. Work on establishing expectations for learning and performance, promoting learner motivation by pointing out benefits, and engaging exemplary learners. Empower learners to select and access materials when they need them. Then trust that the learners can take it from there.

- Focus on context: Focus on what learners need to be able to do in context, not just on what they need to know. Adults organize what they are learning primarily on the basis of what it helps them to do. Learning content in a vacuum is often frustrating and confusing. It’s always important to invite learners to imagine where they will apply their learning as they begin.

- Curate effectively: Curate materials that are the most relevant, reflect quality characteristics, and are likely to appeal to learners. Recommending high-quality learning resources is a huge value for people who need access to materials just in time, and is the whole point of learning environment design.

- Provide variety and depth: Because we don’t always know what learners will bring to the table or exactly how they will apply the learning, the chance of having relevant resources is increased when the resources are varied (within the scope of the vision). Even within a unifying purpose, you can have many differences—in angles on a topic, points of view represented, preferences for learning materials (text-based or video), levels of depth (novice, intermediate, or expert), and so on. The environment will be most valued when it continues to be useful even as learners actively develop their knowledge base and skills.

- Make access easy: Make resources easy to find and access, both electronically and person-to-person. Avoid aggregating resources in a list that is little better than the first pages of a browser search—just a jumble in which it is difficult to find what you need.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

As this chapter has conveyed, the processes of learning environment design are multifaceted and iterative. While they may seem complex, they don’t have to be over engineered. Done well, your efforts to ensuring that learners have access to a robust learning environment for their ongoing development needs will be highly valued.

The beauty of a learning environment is that it can grow over time, just like a lovely garden. Start with the essential pieces and add additional components as time allows (with the help of learners and subject matter experts, if possible). Notice what learners use and what they seem to be missing, and respond accordingly. Keep in close touch so you can anticipate changes in their needs and monitor the effectiveness of the curated resources.

Some learning environments may become unnecessary, but most can gradually change and evolve—simply becoming more rich and valuable over time. The processes of learning environment design can help you lay a good foundation and continuously improve the environments you assemble.