At the time of these writings, spring of 2012, the economy in United States is in a major downturn. Some analyst would say the country is in a recession, while others would disagree. Either way, the slowing economy, which transcends across the American borders into the European Union and beyond, is giving a new blow to knowledge worker-lead KM project teams.

Today’s knowledge workers, and KM professionals for that matter, are required to change their business structure and the way their KM implementations are managed to enable their projects to remain under budget, meet deadlines, and most important, pay off. Focusing on knowledge sharing, Internet-based applications and virtual access to data, knowledge workers are emerging as a driving force in the collaborative implementation of KM. However, given the high risk for KM implementation failures, the new breed of knowledge workers required to lead such teams must have a multitude of skills, including business, technology, team-building, project management, communication skills, and leadership in order to be successful.

In the words of Rebecca Barclay,1 these new breed of knowledge workers must possess vision, strategy, ambassadorial skills, and a certain je ne sais quoi. This is true especially when we consider the traditional methods of calculating return on investment (ROI), which are often ill-suited to measuring the strategic impact of KM applications and initiatives, in particular those applied to customer-facing systems such as CRM. That’s because KM can have a profound strategic impact on a company, far beyond improving processes and productivity. KM can fundamentally change the way a company view its business, its products and even its business opportunities.

Knowledge workers or infoknowledgist are workers whose main capital is knowledge. Typical examples may include software engineers, architects, engineers, scientists, and lawyers, because they “think for a living.”2

What differentiates knowledge work from other forms of work is its primary task of “nonroutine” problem solving that requires a combination of convergent, divergent, and creative thinking.3 The issue of who knowledge workers are, and what knowledge work entails, however, is still debated. One might consider a definition of knowledge work which includes, “all workers involved in the chain of producing and distributing knowledge products,” which allows for an incredibly broad and inclusive categorization of knowledge workers. It should thus be acknowledged that the term “knowledge worker”4 can be quite broad in its meaning, and is not always definitive in who it refers to.

Therefore, the need for a new breed of knowledge worker’s, ones that must redefine their roles and become more business focused, is evident. In addition to possessing business acumen, this new breed of knowledge worker also must be able to approach KM ROI with a new view, one toward establishing both an initial justification for projects, and a very clear baseline for ongoing management decisions and incentives. The main goal should be to increase knowledge sharing, with very specific deliverables, including but not limited to:

•Cultivating employee satisfaction, which should lead to an enhanced customer service.

•Rising individual and program effectiveness, productivity, and responsiveness.

•Increasing the opportunity for communication and collaboration throughout the organization.

•Crafting knowledge and tools needed to do the work available for sharing via the Internet.

•Fostering innovation as the outcome of sharing of knowledge and best practices.

Knowledge Workers as Change Agents

KM is for the most part a product of the incredible changes of the 1990s. Economic globalization expanded, bringing about new opportunities and an aggressive increase in competition. As a result, companies reacted to it by downsizing, merging, acquiring, reengineering, and outsourcing their operations. Benefiting from the latest advances in computer information systems and network technology, businesses were able to streamline their workforces and boost up productivity and their profits. Higher profits, low inflation, cheap capital and new technologies all helped fuel the biggest and hottest bull market the U.S. economy had ever seen. Employment levels were at record highs and skilled workers in high demand. Businesses came to understand that by managing their knowledge they could continue to increase profits without expanding the workforce.

It was in face of those challenges that KM began to attract the attention of the federal government, which was also experiencing profound changes during the 1990s. Payrolls were cut by 600,000 positions; the use of information technology was expanded to improve performance, and management reforms were enacted to improve performance and to increase accountability to the American people. KM presents to the government today a major challenge. The federal government faces serious human capital issues as it strives to improve service and be more accountable. It must compete for workers, as its workforce grows older. Employees of the federal government are older on average than workers in the private sector. Fifty-eight percent of all federal employees were aged 45 or older in March 2009, and almost 25% were aged 55 or older. In contrast, only 42% of wage and salary workers in the private sector were 45 or older in 2007, and 18% were 55 or older.5 This means that unless the knowledge of those leaving is retained, service to citizens will likely suffer.

What all this data means is that executives will no longer be able to rely on information technologies alone to take care of the company’s competitive advantage. In addition, organizations will no longer be able to rely on people the way they have been trained in the existing educational, organizational, and business models. In today’s global economy, the right answer in one time and context can become wrong solutions in another time and context. By the same token, best practices may become worse practices, unless they are constantly analyzed and revised for their sensibility, which can impair business performance and competence. Thus, the logic of yesterday’s success doesn’t necessarily dictate the success of today and certainly won’t dictate the logic of success for a brand-new tomorrow.

In order to succeed, knowledge workers must adjust their vision and humbly grab a hold of their je ne sais quoi and react to it by evaluating and reviewing KM practices and strategies, as a catalyst tool to refocus and reanalyze business data. Believe me, this is just the beginning. In the next five years, information will continue to flow at the speed of light, making it harder and harder for CEOs and senior staff to hold their lines in this supercharged economy. Along with tremendous change in the public and private sectors we see an explosive growth in the Internet and the emergence of e-business and e-government. There is so much information available and pushed at us that at times it is very easy to drown in an information overflow. Yet, the work is changing at such a fast pace that our need for constant and up-to-date knowledge that enables us to respond to rapid changes in the workplace continues to widen every day, every minute. Thus, one of the main challenges knowledge workers face is to seek better ways to help professionals to learn and work smarter. KM is one of the most reliable means to address human capital issues and to take business, and e-business for that matter, to the next level.

KM offers a tremendous edge for business advantage, but only if taken seriously and implemented correctly. Enough of fancy data mining, complex business integration, and strategy meetings lineup and focused on technology and systems to promote KM! I always believed the mantra that success is vision in action. Knowledge workers must have a vision of what they need to achieve, without biased influence of technology or past generation information systems models. We must reinvent ourselves, and the KM systems we rely on, all the time.

To remain competitive, a business must focus not only on generating profit but also on educating employees and growing their capabilities to take care of customers’ needs. Driving a business from the perspective of knowledge and learning rather than strictly from a financial bottom line will give companies a competitive advantage. Knowledge workers are key professionals in this process. Companies are still underestimating the value of knowledge workers for increasing the competitive advantage of the organization and turning the company into a learning company. Most companies are just starting to realize the value of knowledge workers, most of them within the operating groups, which are beginning to rely on them on marketing calls, pre- and post-sales meetings and high-level interaction with customers and potential customers. Knowledge workers add great value in these areas, as typically they are able to bridge the gap between information, knowledge and a firm’s customer base. And, because of their value, they are increasingly being asked to interface with boards of directors as well.

As the speed of business increases, so does the rate of professional turnover inside companies, particularly in the professional service sector. Whenever knowledge walks out of the door organizations need to start projects from ground zero, the value of knowledge workers and KM programs becomes very evident. Lost knowledge takes a tactical toll as companies spend money to re-create it and bring people up to speed. By managing organizational knowledge, a knowledge worker changes organizational culture, people become empowered to make decisions and cycle times are reduced. If you want to find a suitable knowledge worker or if you are wondering yourself if you have the talent it takes, be aware that the best knowledge workers are driven by the challenge of changing how organizations think about knowledge, and about themselves. Knowledge workers are real visionaries, and there is not enough salary, title, or any other corporate perks to motivate them more than the challenge of finding solutions and remaking the thought process that drives them.

Overcoming Organizational and Behavioral Changes

One of the main challenges KM faces today is with regard to organizational and behavioral changes. These are the most difficult tasks when implementing anything, in particular KM. Implementing technology, buying software, is the least complex variable of the equation. Thus, today’s knowledge workers must be aware of these challenges.

In the past, behavioral changes were not taking so much into consideration. Decisions were made from the top-down and all the organizations underneath just adapted to it. Today, organizations are much more decentralized and the global economy and shorter business cycles allow for options people didn’t have before. No longer are professionals looking at positions within their companies as permanent. Typically, professionals move around within two to three years. Whatever can be done to minimize turnovers becomes very important, as along with capturing the knowledge of those leaving before they do so.

To this extent, KM professionals are in essence change agents, acting as catalysts for change. They should be the ones chosen to bring about organizational change. Corporations often hire senior managers or even chief executives because of their ability to effect change.

Fostering Change Through Mentoring

As a formal, and often informal, relationship between two people—a senior mentor and a junior protégé, mentoring has been identified as an important influence in professional development in both the public and private sector. The war for talent is creating challenges within organization not only to recruit new talent, but also to retain talent. Benefits of mentoring include increased employee performance, retention, commitment to the organization, and knowledge sharing.

Many organizations run formal stand-alone mentoring programs aimed at enhancing career and interpersonal development. But formal mentoring programs have structure, oversight, and clear and specific organizational goals. Overall, organizations should implement formal mentoring programs for different purposes, including but not limited to:

•To help new employees settle into the agency

•To create a knowledge sharing environment

•To develop mission critical skills

•To help accelerate one’s career

•To improve retention.

Mentoring is a good strategy to promote desired organizational behavior. Not only is it a good channel for knowledge transfer, but it is also an effective way to develop loyalty and accountability among professionals, in particular among those being mentored and the ones who mentor them. I often use mentoring strategies to get those being mentored, let’s call them disciples, in line and unified with a particular goal at hand and to give them vision. The dynamics invariably work because they feel ownership for the project, an integral part of it. Instead of considering themselves a hired hand (compensated by salaries), mentoring, or discipleship, gives them the vision they need to achieve success.

Over the years, I’ve seen mentoring evolve from an experimental technique to management strategy to a full-blown cult. Seasoned professionals offer guidance to aspiring entrepreneurs. Wise alumni take uncertain young graduates under their wings. Those who’ve kicked drugs help addicts who want to quit. Cancer survivors give hope to the newly stricken. Mentorship can be an effective strategy today’s knowledge workers can use. However, if you are going to play the role, you need to understand what your disciples need and how to practices the fine art of encouragement. If you can always be a source of encouragement for your organization and teach the employees to do the same, I guarantee you will have a tight team, brought together not for salary, titles, or corporate perks, but for a vision, a dream and the feeling of purpose and self-worth. A small team like this can win big battles!

Keep in mind that mentoring is a communication strategy; it enables individuals to engage in conversations and relationships directed at enhancing career satisfaction, professional development, and professional practice. Mentoring is a longerterm relationship in which someone with more experience and wisdom (mentor) supports and encourages another (mentee/protégé) as that individual grows and develops professionally and personally. In mentoring the focus is mainly on role modeling and guidance rather then on supervision and instruction.

Now, be careful not to turn mentoring into a commodity, and don’t let anyone else do it either. The danger in mentoring, as a KM strategy, is that those being mentored tend to believe they should have a mentor who saves them, guides them, and watches out for them for the rest of their careers. In other words, make sure they don’t check off. As mentors, knowledge workers may play many roles, from being an active guide and occasional counselor, to a constructive critic. The more hats you can wear, and wear well, the better, but it’s rare to find one person who can do all of the above.

The Five Phase Mentoring Relationship Model

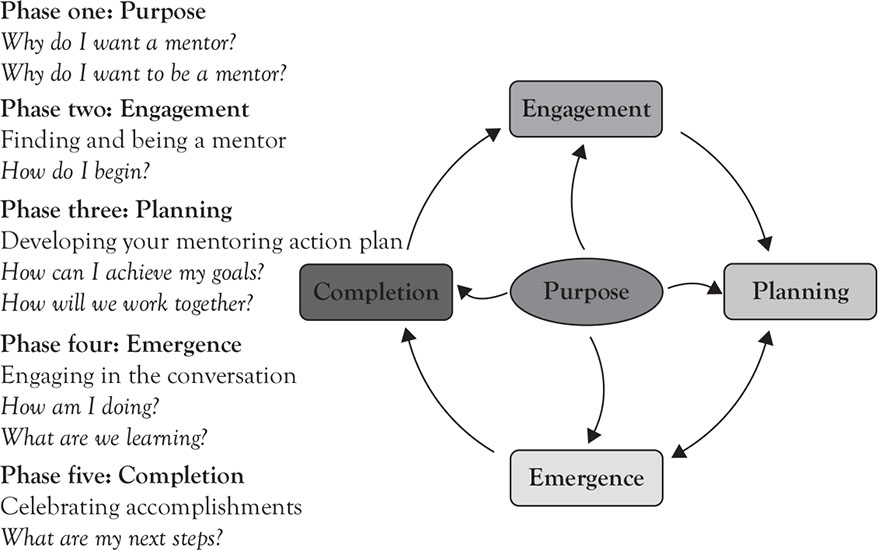

When mentoring groups or even individuals, as depicted in Figure 2.1, there are many techniques to aid you in the process. The Five Mentoring Relationship Model was designed by Donner Wheeler and Integral Visions Consulting6 to guide mentoring relationships from the establishment of the purpose of the mentoring relationship, through engaging the right mentor, establishing a plan for the mentoring, the emergence and ongoing activity of the relationship, and honoring the achievement of goals and completion of the relationship.

Figure 2.1. Five phase mentoring relationship model.

Source: Cooper & Wheeler (2007) Building successful mentoring relationships, http://www.donnerwheeler.com/Programs_and_Services/Mentoring, last accessed on 8/1/2012.

Today’s knowledge worker should evangelize the practice of building mentoring programs into their organization’s human resource departments, their own KM group, or even making mentoring a formal responsibility of managers. Make sure that mentors and mentees do have a set time together, where participants discuss expectations and map out how and when to fulfill them. Keep in mind that contact between mentor and mentee is sometimes as informal as a weekly telephone check-in or occasional excursions out of the workplace, where both parties feel free to let down their hair. At the other extreme are programs with written contracts, structured activities such as “shadowing” (where the mentee follows the mentor around for a prescribed period), and formal evaluation of the mentoring relationship by a third party.

Some people are hesitant to approach a mentor for fear of being a drain on their time and energy. However, the high degree of satisfaction in helping someone develop and the pleasure of being exposed to new ideas are always rewarding and responsible for keeping such programs flowing. For their part, mentees learn new skills, new competencies and the complex politics of an organization. And the company gains by boosting motivation and advancement, which leads to greater employee retention. Thus, mentoring is a win-win situation.

Listening is also a very important aspect of mentoring. It involves hearing, sensing, interpreting, evaluating, and responding. Good listening is an essential part of being a good leader, and the cornerstone of this new breed of knowledge workers. You cannot be a good knowledge manager unless you are a good listener. You as a knowledge worker must be very aware of the feedback you are receiving from the people around you. If you are not a good listener, your future as a knowledge worker will be short.

Good listening includes a package of skills, which requires knowledge of technique and practice very similar to good writing or good speaking. In fact, poor listening skills are more common than poor speaking skills. I am sure that you have seen on many occasions two or more people talking to each other at the same time. In improving your listening skills, be aware that there is shallow listening and deep listening. Shallow or superficial listening is all too common in business settings and many other settings. Most of us have learned how to give the appearance of listening to our supervisors, the public speaker, and the chair of the meeting while not really listening. Even less obvious is when the message received is different from the one sent. We did not really understand what the message is. We listened, but we did not get the intended message. Such failed communications are the consequences of poor speaking, poor listening, and/or poor understanding.

The following attributes of good listening are suggestive of the skills needed for a new breed of knowledge workers. There is some overlap between the various attributes, but each suggests something different.

•Attention—This is the visual portion of concentration on the speaker. Through eye contact and other body language, we communicate to the speaker that we are paying close attention to his/her messages. All the time we are reading the verbal and nonverbal cues from the speaker, the speaker is reading ours. What messages are we sending out? If we lean forward a little and focus our eyes on the person, the message is we are paying close attention.

•Concentration—Good listening is normally hard work. At every moment we are receiving literally millions of sensory messages. Nerve endings on our bottom are telling us the chair is hard, others are saying our clothes are binding, nerve ending in our nose are picking up the smells of cooking French fries, or whatever, our ears are hearing the buzzing of the computer fan, street sounds, music in the background, and dozens of other sounds, our emotions are reminding us of that fight we had with our mate last night, and thousands more signals are knocking at the doors of our senses. Focus your attention on the words, ideas, and feeling related to the subject. Concentrate on the main ideas or points. Don’t let examples or fringe comments distract you.

•Don’t Interject—There is a great temptation at many times for the listener to jump in and say in essence: “Isn’t this really what you meant to say.” This carries the message: “I can say it better than you can,” which stifles any further messages from the speaker. Often, this process may degenerate into a game of one-upmanship in which each person tries to outdo the other and very little communication occurs.

•Empathy, not sympathy—Empathy is the action of understanding, being aware of, being sensitive to, and vicariously experiencing the feelings, thoughts and experience of another. Sympathy is having common feelings. In other words as a good listener you need to be able to understand the other person, you do not have to become like them. Try to put yourself in the speaker’s position so that you can see what he/she is trying to get at.

•Eye contact—Good eye contact is essential for several reasons. By maintaining eye contact, some of the competing visual inputs are eliminated. You are not as likely to be distracted from the person talking to you. Another reason, most of us have learned to read lips, often unconsciously, and the lip reading helps us to understand verbal messages. Also, much of many messages are in nonverbal form and by watching the eyes and face of a person we pick up clues as to the content. A squinting of the eyes may indicate close attention. A slight nod indicates understanding or agreement. Most English language messages can have several meanings depending upon voice inflection, voice modulation, facial expression, etc.

•Leave the Channel Open—A good listener always leaves open the possibility of additional messages. A brief question or a nod will often encourage additional communications

•Objective—We should be open to the message the other person is sending. It is very difficult to be completely open because each of us is strongly biased by the weight of our past experiences. We give meaning to the messages based upon what we have been taught the words and symbols mean by our parents, our peers, and our teachers.

•Receptive Body Language—Certain body postures and movements are culturally interpreted with specific meanings. The crossing of arms and legs is perceived to mean a closing of the mind and attention. The nodding of the head vertically is interpreted as agreement or assent. Now, be careful, as nonverbal clues such as these vary from culture to culture just as the spoken language does. If seated, the leaning forward with the upper body communicates attention. Standing or seated, the maintenance of an appropriate distance is important. Too close and we appear to be pushy or aggressive, and too far and we are seen as cold.

•Restating the message—Your restating the message as part of the feedback can enhance the effectiveness of good communications. Take comments such as: “I want to make sure that I have fully understood your message....” and then paraphrase in your own words the message. If the communication is not clear, such a feedback will allow for immediate clarification. It is important that you state the message as clearly and objectively as possible.

•Strategic Pauses—Pauses can be used very effectively in listening. For example, a pause at some points in the feedback can be used to signal that you are carefully considering the message that you are “thinking” about what was just said.

•Understanding of Communication Symbols—A good command of the spoken language is essential in good listening. Meaning must be imputed to the words. For all common words in the English language there are numerous meanings. The three-letter word “run” has more than one hundred different uses. You as the listener must concentrate on the context of the usage in order to correctly understand the message. The spoken portion of the language is only a fraction of the message. Voice inflection, body language, and other symbols send messages also. Thus, a considerable knowledge of nonverbal language is important in good listening.

•You cannot listen while you are talking—This is very obvious, but very frequently overlooked or ignored. An important question is why are you talking: to gain attention?

In summary, good listening is more than polite silence and attention when others speak, and it’s altogether different from manipulative tactics masquerading as skill. It is rather a high virtue, a value and a reflection of bedrock belief that learning what other people have on their mind is a wise investment of one’s time.

Chapter Summary

This chapter focused on the knowledge worker. After addressing the KM environment at organizations and its challenges in chapter one, this chapter provides a profile of the knowledge worker, not necessarily as an information technology professional, but mainly as a change agent. Challenges dealing with organizational and behavioral changes were discussed, as well as the ever-increasing need for fostering change at organizations. A special attention is given to mentoring relationships at learning organizations.