CHAPTER 5

The Luxury Client

In earlier chapters, we speak repeatedly about the consumer. This is, in fact, something of a misnomer. A consumer, as the name implies, consumes the products he or she purchases. We have already seen in Chapter 2 that in luxury there are no products, only special objects that clients want to acquire and keep. Someone purchasing a Rolex watch or a Hermès handbag is not going to consume the product, then go back to the store to acquire a new one.

The client purchases iconic objects on special occasions and does so with a special mood or spirit. Even repeat purchases of objects such as a bottle of perfume or champagne are exceptional events, charged with emotional and social content.

In this chapter, we will first ask who the luxury clients are. We will then study how such clients behave, before looking at differences in national behavior.

Who Are the Luxury Clients?

Luxury clients are in fact the very rich, and, also . . . everybody. We will begin by looking at some quantitative analysis that has been done, mainly in the United States, to see who those clients buying a bottle of champagne or an expensive watch really are.

The Rich, the Very Rich, or Everybody?

There have been several studies analyzing the very rich. According to one, conducted by EuroRSCG in 2002,1 there were 7.2 million people in the world with net assets exceeding US$1 million. Of these, one-third lived in the United States. Countries such as France, the United Kingdom, and, strangely enough, China, each had approximately 300,000 millionaires.

A United Nations report published in 2006 said that 1 percent of the world’s population (that is, some 66 million people) had assets of over €500,000. While the currencies used in each are different, the two studies are complementary.

Obviously, having a million dollars in China is not exactly the same thing as having a million dollars in the United States, where the cost of living is very different, and where the disposable income is also quite different. However, purchasing a Tiffany ring for €10,000 is somehow a similar step.

Every year, Forbes Magazine publishes a list of the world’s wealthiest individuals, with a special section on the richest Chinese men. In the United States, there are said to be 170 billionaires. The Swiss magazine, Bilan, for its part, reports that there are 286 people living in Switzerland who have assets of above a €1 billion euros. However, do you need to be a billionaire to buy a Chanel handbag? Any middle-management executive from a DINK (double income, no kids) household can afford one.

Also, Cap Gemini Merill Lynch publishes yearly the number of individuals who have financial investments of at least one million dollars. Published in September 2011, the 2010 figures distinguished 10,900,000 high-net-worth individuals, with 3.4 million coming from North America, 3.3 million coming from Asia, which is ahead of Europe with 3.1 million individuals. By nationality, United States is first with 3.1 million, Japan second with 1.7 million, Germany third with 924,000 individuals, followed by China (535,000), the United Kingdom (454,000), and France (396,000).

Researchers have tried to move from the very rich to those who could purchase some or many luxury objects. Don Ziccardi2 identifies four consumer segments.

When the economy is going well, all these groups buy luxury goods. When the economy is in recession, the majority does not have to cope with major drops in their income and their disposable income may not really vary. But their assets, made up in large part of real estate and financial investments, drop in value: They feel less inclined to spend their money and are careful and restrained. Of course, while the middle-money category reacts more than the others in this regard, this is a general phenomenon that can be observed across the board.

So, then, are millionaires or members of these four categories the only luxury clients? Obviously not. We noted earlier the total luxury business amounted to around €220 billion, including some at wholesale or export prices. If the millionaires were the only clients, they would each purchase goods to the value of more than €21,000 a year. While this segmentation of the very rich may be a useful outlet for high-value jewelry pieces or a high-performance Porsche or Ferrari, it is not a true reflection of luxury clients as a whole.

When asked “Have you bought a luxury product in the last 24 months?” 63 percent of respondents in developed countries answered “Yes.”3 This is actually the real group of luxury clients: more than half of the general population in developed countries. And the rapid growth rate of this industry (an annual average of 8 percent) results from the fact that every year a new group of middle-class consumers from developed or developing countries can, for the first time, afford to buy a bottle of champagne, a €1,000 handbag, or a €1,500 watch. With the increased accessibility of such goods, luxury is, for 63 percent of people in developed countries, at least, becoming part of their everyday experience.

This is, of course, still a very far cry from the 4,000 women in the world who can afford an haute couture dress, or even from the 10.9 million who can afford an expensive piece of jewelry. The luxury client is almost everybody. But he or she purchases a luxury object very rarely.

The Excursionists

The word excursionist was coined in 1999 by Bernard Dubois and Gilles Laurent4 and arose from their observations from an early study by the Paris-based research company Risc Consumers in developed countries. These findings are presented in Table 5.1.

TABLE 5.1 Breakdown of Luxury Clients in Developed Countries

Source: Dubois and Laurent.

| Have not purchased a luxury product in the last 24 months | 37% |

| Have purchased a luxury product in the last 24 months | 63% |

| Have purchased more than five pieces | 12% (i.e., 20% of purchasers) |

| Average number of purchases | 2 |

Their findings showed that, apart from the happy few (12 percent) who had bought more than five items in the previous two years and who obviously represented a very large volume of the total market, the largest group (51 percent of the population) had bought between one and five items. What immediately leaps to mind here is the lower-middle-class group, who are very careful about their general spending and look for special promotions in the supermarket, but may decide to buy a Cartier watch for their son’s graduation or a small Tiffany engagement ring for their future daughter-in-law. Dubois and Laurent used the word excursion to describe how this group approached the purchase of luxury items. Entering a Cartier or Tiffany store was, for such consumers, a bit like taking a boat ride or visiting a museum. The interesting question Dubois and Laurent asked themselves was what these excursionists were expecting from their ride to a luxury store. They investigated further, asking the question: “What were you looking for?” The answers they received from the excursionists were as follows:

- They expect the product to be of outstanding quality, both in the materials used and in the service. This is not like visiting a supermarket: It is a very special experience and must be rewarding.

- They expect the product to be expensive. For the function it satisfies, the luxury product should clearly belong to another price range: The purchase is not a natural or matter-of-fact activity and the price should reflect this.

- They want to be sure that the object they acquire is scarce and difficult to obtain, open only to a very few individuals.

- They expect the shopping experience to provide a multisensuous moment: When they walk into the store, across the thick wall-to-wall carpet, they want to be surrounded by sophisticated music, to see beautiful objects, and to know that what they are about to do will be worth it. And, of course, they expect sales staff to treat them as people who are doing something exceptional.

- They expect to come to a world that has its roots in the past. They want to make a purchase that is timeless. They want their act to become part of an environment that has always existed and will always exist.

- They know that their purchase does not make too much economic sense and they are happy with that. They accept the fact that what they are doing is slightly futile or unnecessary. They speak of jewelry or perfumes in the way, for example, others may speak of a Jaguar: They are not concerned with its engine or its technical characteristics, but speak about the luxury of the passenger space.

The excursion must be something memorable and different. This is why in-store service is so important in the luxury field. But having described the excursionist model, it is important to remember that this is part of a larger movement that analyzes the marketing and consumer process, not in terms of the segmentation of individuals, but in terms of different situations in life and explaining different purchasing behaviors.

The New Consumer

New clients will evaluate products and buy them as a function of their individual situation. For example, a woman may in the course of one day buy Zara jeans, a Celine jacket, and Wolford hosiery. She may then end her day shopping at Carrefour and buying coffee because of a cut-price promotion. This apparently changing behavior is what specialists have tried to understand: Customers today have new expectations and new patterns of behavior.5

New Customer Expectations

Customers are not rational when they purchase a luxury object. They don’t claim to be rational. More than anything else, they value the affective and aesthetic contents of their purchase and perceive the different products along such lines.

They are affective because they consider their own pleasure to be more important than any other rational criteria. To judge a product on rational criteria would reduce their shopping pleasure. As they compare different products, they value intangible elements like the sophistication of the atmosphere in the store, the opportunity to go to an area of the town where they can meet people, or, even better, famous people. Even the type of music they hear in a given store can condition the way they perceive products from a particular brand and, ultimately, the way they buy.6

This affective component of the consumer information process is used in advertising, as we will see in Chapter 8. Luxury advertising is not only based on information. It is based on the fact that it should surprise, attract, and communicate a specific mood.

A second expectation relates to a need for beauty, the belief that a product should be evaluated by its shape, its special feel in the hand, the types of fashion models used by the brand in its advertising, or the aesthetic value of its advertising.

This is one of the reasons that the aesthetic elements of a brand are so important in its development. People associate different aesthetic values with different brands. Gucci and Yves Saint Laurent belong to completely different universes. This should be reflected in the shape of the perfume bottles, the concept of the ready-to-wear stores, and the shopping bags clients are given for their purchases.

New Customer Behaviors

Customers are eclectic. They want to be different from the crowd and they want to indicate to everybody that they know what they are doing. Patrick Hetzel, a French economist, speaks of a toolbox by which customers can define what is best for their given mood or their specific style.7 They do not want to rely on a single brand. The “total look” (all Chanel or all Versace) is completely out of fashion today: It does not show who you are and what you have decided for yourself. A creative mix between Givenchy and Zara shows that you are creative and that you have taste.

Now, though, eclecticism has some limits. Customers still want to belong to a group and are rewarded by this group for the choice they made. While, fifteen years ago, people wanted to be identical to their group of references or their close friends (at school, students wanted to carry the same brand), this is no longer so. Today, they want to be similar to a very small number of individuals that they have selected as part of their small, tribal group. The social norm still exists and is still very strong, but its base is scattered between myriad subgroups that are organized along different types of activities or behaviors.

Consumers are also looking for hedonistic values. They prize their own pleasure more than anything else. Here again, they do not look only for the functional elements of a product’s attributes, but to the imaginary world that they have created themselves and that becomes their own world, leading to their own vision of luxury in general and individual luxury brands in particular.

This brings us back to the cultural dimension described at the beginning of Chapter 2. Each customer’s individual vision of a given brand integrates aesthetic and cultural values, often of a specific national atmosphere, and of what this brand can and cannot do.

Consumers can be fragmented in their expectations and in their behavior and can change rapidly over time.

The result for luxury brand management is quite clear: Sales trends are changing rapidly and brands that are successful are those that are able to give an added cultural, aesthetic, and hedonistic value to their overall identity.

Are Clients from Different Nationalities Similar?

The question now is if there is such a thing as a worldwide client, if people from different nationalities behave in the same way.

Pierre Rainero, manager of market research and communication for Cartier, has an opinion:

The Italians like watches that are slightly flashy and insist on a mechanical movement. They collect them and may change their watches several times per day. The Germans prefer quartz watches with a very simple design: rigor and effectiveness. The French have a strong preference for the engineer’s watch: sporty and full of several chronometer dials.8

Different European nationalities also have different ways of wearing a piece of jewelry.

In Germany, women who have a management job purchase their jewelry pieces themselves and wear them in a triumphant way. In the style, they look for the purity of the raw materials and they like the stone to be set up in a very natural way. The Italians are looking for movement, so they like baroque pieces. They are interested in the curves of the jewel and the way gold is set up. Ring shapes are moving like a piece of fabric. In Japan, but also in France or in Spain, group pressure is stronger than individual taste. The French, afraid of social critics, are looking for reasonable jewels, which must be balanced and appear in good taste.9

So, even within the European continent, there are large differences. Extend this to the world at large and the differences become even more pronounced.

Differences in Consumption Patterns Among Nationalities

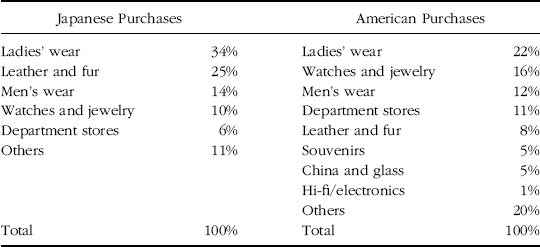

Global Refunds is a Scandinavian firm that specializes in handling value-added-tax returns for tourists. When tourists make a purchase in a luxury store, the store completes a form and sends it to Global Refunds, which, in turn, adds up all the tax-free purchases and sends the appropriate tax refund to each tourist after he or she has left the country. Global Refunds is therefore in the best position to assess what tourists from different nationalities purchase in France. Table 5.2 sets out its findings, based on an average duty-free purchase of €675.

TABLE 5.2 Breakdown of Purchases of American and Japanese Clients in Paris

Source: Global Refunds Newsletter, 2001.

Some differences are striking: Japanese tourists purchase three times the amount of leather goods than do Americans. Americans have a more diversified mix of purchases but buy significantly more jewelry and department-store products (including, probably, perfumes). Japanese tourists concentrate 59 percent of their purchases in ladies’ wear and leather accessories.

Before continuing with the analysis, it will be useful to take a look at the different product categories.

Ready-to-Wear and Accessories

The ready-to-wear category is, in a way, a specialty of the Japanese. Japanese purchases generally represent 30 to 40 percent of the worldwide volume of French and Italian upscale fashion brands, making the Japanese market the leading one in the world, well ahead of the United States, which represents only 10 to 15 percent.

This is why Japan is a key market for fashion brands and for leather goods, in which it probably represents an even higher percentage than that indicated here.

The Japanese fashion interest extends to Southeast Asia, partly because it is often an important duty-free zone for Japanese tourists, and also because the citizens of Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan, and Thailand, who generally have less money to spend than the Japanese, are very interested in this product category.

The situation in China is slightly different. In 2010, China contributed less than 10 percent of worldwide volume of the ready-to-wear and accessories category. Like the Japanese, the Chinese are very interested in fashion brands, and even if the business is growing by approximately 30 percent a year, it still remains smaller than Japan. At the present rate of growth, China’s market will be bigger than Japan’s in 2015. With the arithmetic drop in the Japanese percentage from 30–40 percent to 20–10 percent, they both will represent more than 50 percent of sales for many brands.

Also, products sold in China are quite different from those sold in Japan. In Japan, women purchase goods themselves. In China, men are the main purchasers, which is why men’s brands are generally doing very well there, much better than women’s brands. Now, when men purchase fashion items for their wives or their friends, they buy less ready-to-wear and confine themselves to simple tops or jackets, for example. They also buy a larger percentage of accessories and handbags, with a strong preference for iconic products that appear in advertising and that they know will be the ideal gift.

European markets are strong in fashion, with a large part of the purchases being made by executive women. This is where brands like Armani and Jil Sander have a strong following.

Perfumes and Cosmetics

Unlike ready-to-wear, perfumes are not very important in Japan, with sales representing just 1 percent of worldwide consumption. In Japan, perfumes are often viewed as products to cover up and hide the natural smell of the body. They are sometimes perceived as an intrusion, something that a woman imposes on her environment. In many companies, there is an official or informal rule prohibiting the use of perfumes in the workplace, and they are also not well received in the subway or in other public places. Teenagers wear perfumes as a way to express themselves, but many lose the habit when they start work. In some areas of Japan, the rumor persists that perfumes are unhealthy for young babies, causing many mothers to stop using perfumes altogether.

Perfume brands in Japan try to develop usage by promoting the sophistication of the products and as a means of self-expression at parties or special events.

North and South America are strong perfume markets, with approximately 30 percent of worldwide consumption. The Middle East is also an area where perfumes are much appreciated and consumed in large quantities.

Cosmetics are a different matter; Japan is a very strong market. The Chinese market, too, although still small, is both a perfume and a cosmetic market.

The perfume market is also segmented geographically, and very few fragrances are appreciated worldwide. Women in the Latin countries tend to like fresh and floral notes—citrus and lavender fragrances that are not much liked elsewhere. Anglo-Saxon women prefer heavy perfumes, with a very strong heart and a strong presence. Asian women are divided. Japanese women like very light perfumes, so that a product like Tartine et Chocolat, designed for babies and very young girls, is a top seller among mature women.

The challenge in launching a new perfume with global ambitions is to find a note that is light enough to please Japanese women, strong enough to satisfy American or German women, and fresh and floral enough to satisfy Latin women. Products that are globally successful are those that find a way to cut across these preferences and come up with a completely new note. This is not easy.

Wines and Spirits

In consolidated terms, the wines and spirits market is more or less balanced equally, with approximately one-third of the total business done in each of the three major markets: the Americas, Europe, and Asia. But, as we saw in Chapter 3, there are considerable differences in the types of products favored in each.

Rum is mostly consumed in the Americas. Gin is essentially a British and North American drink. About 60 percent of the worldwide volume of champagne is consumed in France, with very strong additional volume in other European countries. In contrast, whiskies and vodka are purchased everywhere in the world with the same penetration and usage rate and are thus relatively balanced.

Cognac is a product that is also sold everywhere in the world, but with clear differences in types of product consumed in different locations.

What is clear at this stage is that consumer behavior differs from one part of the world to another.

Differences in Attitude Among Nationalities

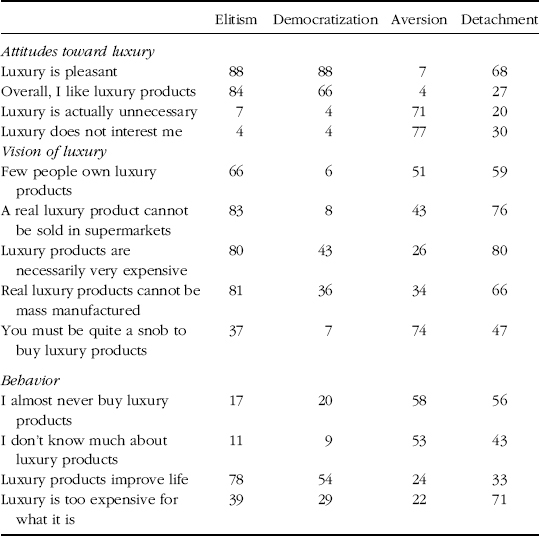

In this section, we describe and discuss the results of a study conducted in 1996 by Bernard Dubois and Gilles Laurent,10 for which they interviewed eighty-six consumers in twelve countries: Germany, the United States, Norway, Austria, Denmark, Poland, Australia, the Netherlands, Spain, Belgium, Hong Kong, and France. The questionnaire was presented in English to business students, who were asked to answer respond to such statements as, “I almost never purchase luxury products,” or “Luxury is pleasant,” and so on. (Although there were thirty-four such sentences, Table 5.3 reports on just thirteen of the major statements.)

TABLE 5.3 Different Typologies of Consumer Perceptions of Luxury (% of respondents agreeing)

Source: Dubois and Laurent.

Despite the fact that questions were put to students, who are not necessarily the best or most appropriate people to ask about luxury goods, four different groups—quite homogeneous and quite different in their responses—emerged.

These groups are quite interesting because they provide a typology of attitudes and behavior that can be used to analyze any group of consumers: These four positions are underlying patterns that can be found in many different groups, even within the same country.

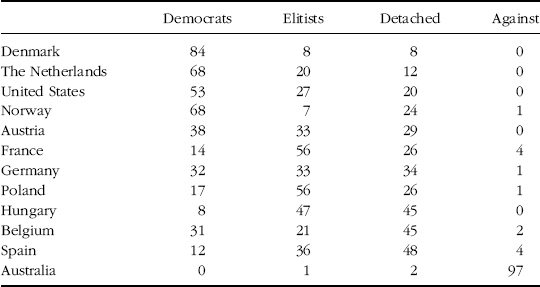

The aim of the study by Dubois and Laurent was to find differences in perceptions among different national groups. Table 5.4 summarizes their findings.

TABLE 5.4 Frequency of Typologies by Country (%)

Source: Dubois and Laurent.

The most striking finding is just how different Australia is from all the others. It is clear that Australians have a very specific culture and seem to have a strong negative attitude toward luxury products in general and the concept of luxury in particular. The luxury world is a world quite different from the normal Australian way of life. This does not, of course, prevent Australian executives from wearing Hermès ties or Rolex watches, no matter how ill-at-ease this may cause them to feel.

There is a group of four or five countries, including Denmark and Austria, which have favorable attitudes toward luxury. While, on average, 20 percent are detached, nobody is opposed to it. In this group, luxury is perceived as positive, but also open and democratic. It is there for everybody to enjoy. In Denmark and Norway, very few belong to the elitist group. In the United States, people are quite favorable to luxury, but divided by a ratio of almost two to one between the democratic group and the elitist group. In a way, in the United States, as well as in Austria and Germany, two clear visions of luxury cohabit within the same population. In other words, this is a market that is very segmented, and one in which different groups must listen to a slightly different story if they are to be convinced. However, it is probable that, in those markets, when asked about luxury, some think of a diamond necklace and others think of a perfume.

In the second group, as shown in Table 5.4, it is clear that we have countries with a relatively strong, detached group of people, who have a positive attitude but generally consider themselves nonusers. The fact is that there is a group of countries, including France, where luxury is perceived as an elitist market, the preserve of the happy few. Spain has a lot of detached people, which is consistent with its relatively small number of luxury brands. If Italy were in the sample, it would probably be quite similar. Belgium, like Germany and Austria, has a pattern where two groups coexist for and against the elitism in luxury, but in Belgium’s case there is also a strong detached segment.

Thus, to the question “Do people from different nationalities behave the same way and do they have similar attitudes?” The answer is clearly “No.” One of the weaknesses of this study is that it does not include two very strong luxury markets: the Italians and the Japanese, not to mention the Chinese and the British. Nevertheless, it is very useful in that it highlights major differences from one culture to another.

The RISC Study

RISC International is a consulting firm specializing in consumer research and brand marketing, and a pioneer of research into attitudes toward luxury in different countries.

RISC conducts studies every year in three major zones: the United States, Japan, and five European countries (France, Germany, Italy, United Kingdom, and Spain). It conducts additional studies in China, Korea, and India. These studies are not public, but we have had access to the 2003 results, which were based on 18,500 questionnaires.

The advantage of RISC studies is that they provide a detailed analysis of attitudes toward luxury in general, then go one step further to gather information on awareness, penetration, and the dream (“If you were to receive a beautiful gift overnight, which brand would you want it to be?”) on a list of forty brands.

They also record purchases in the previous three years in the following product categories:

- Watches (with a retail price of more than €550)

- Jewelry (more than €400)

- High-fashion clothes (more than €2,000)

- Clothes for men and women (more than €500)

- Shoes (more than €250)

- Bags (more than €550)

- Leather accessories (more than €250)

- Other accessories (more than €200)

- Underwear (more than €100)

- Perfumes (more than €40)

- Sunglasses (more than €120)

- Writing instruments (more than €175)

So, with the exception of wines and spirits, most of the product categories are represented here.

Of the forty brands, Armani, Burberry, Cartier, Chanel, Dior, Gucci, Hermès, Hugo Boss, Kenzo, Lacoste, Louis Vuitton, Ralph Lauren, Rolex, Yves Saint Laurent, Calvin Klein, Bulgari, Prada, Dolce & Gabbana, and Cacharel are studied in the seven countries comprising the three major zones. Other brands are adapted to different market situations, with, for example, Loewe for Spain and Japan, Max Mara for Italy and Japan, and Moschino for Italy, Spain, and Japan.

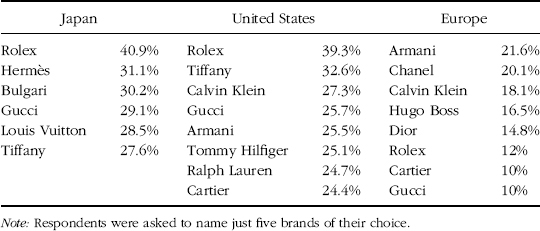

The overall brand interest (the dream) is summarized in Table 5.5.

TABLE 5.5 Top Luxury Dream Brands

Source: RISC International, 2003.

From this we can see that only two brands—Rolex and Gucci—are common to all three zones. Very few of the others—Tiffany, Armani, Calvin Klein, and Cartier—were in more than one zone. Here, again, we can see the differences in perception and in brand status.

In Japan, there is a strong concentration on a few iconic brands, with very high percentages. Also, of the six top brands, only Gucci is really a fashion brand; all the others are high-status jewelry, watch, or leather-goods brands.

In the United States, Rolex records a performance very similar to that in Japan, but the other results are quite mixed. American brands account for half of those mentioned, with two Italian brands—Gucci and Armani—and one French brand—Cartier—making up the rest. There is a mix of casual brands such as Tommy Hilfiger and, in a way, Ralph Lauren, and only one sophisticated high-end fashion brand, Gucci, which is probably known in the United States for its penny loafers, scarves, and handbags.

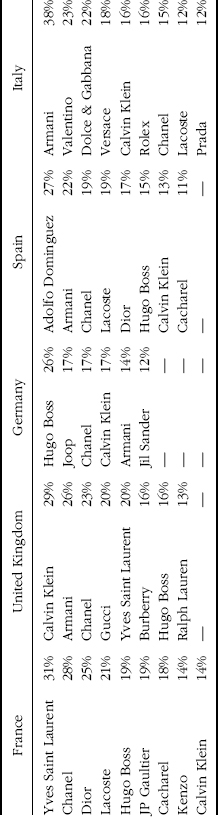

In Europe, the situation is even more complex, as brands have much smaller scores and the situation is quite scattered. To understand this, it is necessary to look at specific performances for each country, as shown in Table 5.6.

TABLE 5.6 Top Luxury Dream Brands

Source: RISC International, 2003.

What is striking here is the strong national bias. In France, no Italian brands seem to get people dreaming, and, with the exceptions of the institutional brands of Chanel, Calvin Klein, Lacoste, and Rolex, Italy has an otherwise all-Italian-brand scorecard.

In the United Kingdom, Calvin Klein heads a table in which the British Burberry brand and another U.S. brand, Ralph Lauren, also appear amid French and Italian brands. Yves Saint Laurent has maintained a very strong image, as in France, despite its low sales, and is hoping product merchandising and sales will follow.

In Germany, a trilogy of German brands—Boss, Joop, and Jil Sander—performed well, along with Chanel, Calvin Klein, and Armani.

In Spain, there is a relatively open market, with a Spanish brand, Adolfo Dominguez, coming out on top. Four French brands, including Dior, appear in the list.

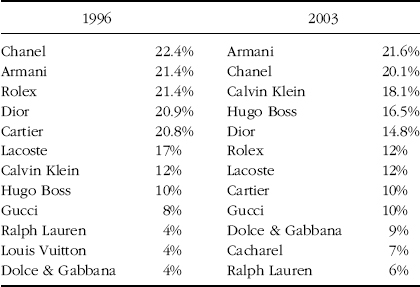

Another approach to the European market is presented in Table 5.7, which compares the results to the same survey conducted in 1996 and 2003.

TABLE 5.7 European Trends in Top Luxury Dream Brands

Source: RISC International, 2003.

- With the exception of Lacoste, the accessible luxury brands—Calvin Klein, Hugo Boss, Cacharel, and Ralph Lauren—have all improved their status. They open stores, they advertise, they generally have several lines with different price positionings, and it works. While this is an interesting strategy, results are strongly dependent on how men respond. Luxury is more normally associated with women, who are responsible for more than two-thirds of luxury purchases. As the RISC study was based on an equal sample of women and men, the responses are skewed in favor of men’s brands or brands that men like and should not, therefore, be considered as an indication of potential market when it comes to men’s and women’s brands.

- The French institutions, in particular, Dior (20.9 percent to 14.8 percent) and Cartier (20.8 percent to 10 percent) have lost attractiveness. This may have something to do with their positioning and their advertising concepts. Only one French brand has maintained a strong performance: Chanel, which is placed in the top three in four of the five European countries.

- The brands that have been overly product-oriented, such as Rolex (21.4 percent to 12 percent) and Cartier (20.8 percent to 10 percent), have stopped providing dreams and aspirations for their customers in 2003, or may not have taken into account that consumers have changed. They certainly regained their strength in 2012.

- The general trend has been to go from institutional brands with strong codes to more relaxed, international brands with no strongly affirmed country of origin.

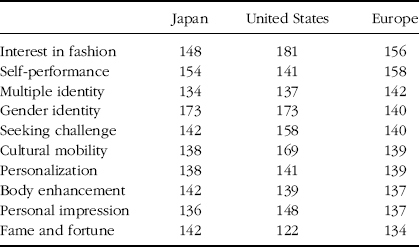

The RISC studies go well beyond presenting brand performances and can explain major shifts in those performances. They can also compare social and cultural trends and the differences in each zone between purchasers and nonpurchasers of luxury products, as illustrated in Table 5.8. Here, the responses of the users of luxury products are recorded and measured against an index of 100 that is used to indicate the level of interest of the average consumer. If we take, for example, the first figure of 148, this indicates that where Japanese respondents indicate an average interest in fashion of 100, those who are luxury-product users register 48 percent higher than the average consumer.

TABLE 5.8 Values Specific to Luxury-Product Users (index of 100 for average consumers)

Source: RISC International, 2003.

There are few differences between the three zones. While, at first sight, it might appear that the Americans have a greater interest in fashion than other nationalities, in fact, luxury product users are less numerous in percentage terms in the United States than, for example, in Japan. They simply stand out from the crowd more than in Japan, where the interest for luxury is more general.

From these results it appears that luxury purchasers all want:

- To be individuals. They seek self-development, individual freedom, personal creativity, and autonomy.

- To mix styles. They play with codes and integrate foreign ways of life.

- To be winners. They have a strong social presence, they seek challenges, and they like to experiment.

- To be distinctive. They want to be different from others and to assert their individuality. They are fashion trendsetters, using their appearance to express their difference, their modernity, and their creativity and to achieve their social ambitions.

- To look and perform better. They care about their body, looking on it as a source of sensations and pleasure, as a partner to their success.

- To keep their vitality—physical, mental, and emotional.

This profile of the user of luxury products could be very useful to define the type of positioning and advertising platform that is most effective today.

At this stage we have moved very far from the classic, conventional, and institutional idea according to which a luxury product is rare and expensive.

We are in a very different ballgame. We are in the realm of the avant-garde and the trendy. The brand and product environment must deal with emotions, with sensuality and physicality, with escape, success, performance, optimism, and the ephemeral. It is no longer the product that is rare and expensive: It is the individual.

On this platform, it is possible to come up with positioning and communication objectives that make a lot of sense, as we will see in Chapter 8.

To finish with the RISC findings, it is possible to derive a comparison between American and European types of luxury brands, as shown in Table 5.9.

TABLE 5.9 Differences Between American and European Luxury

Source: RISC International, 2003.

| United States | Europe |

| Social motivations | Individual motivations |

| Realization of social dreams | Realization of personal dreams |

| Ambition: What would I like to be? | Ambition: realization of emotional desires |

| Perfume: social accessory, brand name | Perfume: me, my identity, my sense |

| Relationship | Emotional relationship |

| Practicality, utility, functionality | Aesthetics, sensuality, style |

| Wearable clothes, always comfortable | |

| Customer-driven brands | Creativity-driven brands |

| User friendly, easygoing brands | Eccentricity, no real sense of utility, no limits |

| All needs, all circumstances | Distance |

| Service | Keeping the dream alive, fantasy |

| Exclusivity: prices and rarity | Elitism |

| High prices are the best luxury sign | Prices |

| Giving value to the buyer | Cultural codes (Hermès) |

| Lifestyles | Intellectual concepts |

| Old England | Ways of being |

| Casual | French brands |

From this table it is clear that American brands are very much in synch with socially active American consumers. They are in fact marketing brands in that they are clearly customer driven. On the basis of American consumer needs, they have defined an accessible, open, relaxed, and casual style.

European brands are clearly creativity driven, in the sense that the creator seems to be given full authority over the content and personality of the brand. They value aesthetics and things that appeal to the senses. For them, function is secondary to the emotion created. They want to maintain a strong distance between the brand’s cultural values and the consumer: Those values should be something in which consumers aspire to participate, to join the happy few. They buy the products in the hope of one day becoming part of this elite group.

The trend today seems to favor the customer-driven American brands, but this may change in the future.

From everything that we have seen in this chapter, it is clear that creating a brand that satisfies every customer in the world is a real challenge. This is a situation in which market research is absolutely necessary, but market research that is based on consumer attitudes and expectations. We will look more closely at this in the next chapter, when we investigate brand identity.

As we finish our review of the luxury client, it must have become obvious that in this very strong marketing environment, where emotional values have an overriding impact on the acceptability and desirability of a product, market research, undertaken in different parts of the world, is an essential tool for success.

In the next chapter, we look at other analytical and management tools that enable us to master one of the most valuable elements of luxury brands: their brand identity.

1. Euro RSCG, “Living a good life,” 2002.

2. Don Ziccardi, Influencing the Affluent: Marketing to the Individual Luxury Customer in a Volatile Economy, MFJ Books, 2001.

3. RISC, The luxury market, 2003.

4. Bernard Dubois and Gilles Laurent: “Les excursionnistes de luxe.” Hommes et Commerce, No. 271, MW 1999.

5. See Patrick Hetzel, “Les entreprises face aux nouvelles formes de consummation.” Revue Française de Gestion, September/October 1996.

6. P. Siberil, “Influence de la musique sur les comportements des acheteurs en grande surface de vente,” thesis, University of Rennes, 1994.

7. Patrick Hetgel, Marketing Experientiel et Nouveaux Univers de Consommation, Editions d’Organisation, Paris, 2002.

8. Corinne Tissier: “Divided Colors of Cartier,” Le Nouvel Economiste, 10 January 1995.

9. Ibid.

10. Bernard Dubois and Gilles Laurent: “Le luxe par delè les frontières: une étude exploratoire dans douze pays,” Decisions Marketing, September–December, 1996.