CHAPTER 7

Managing Creation

In this chapter, we will focus on the creativity that a luxury brand needs to apply to its products or services. Needless to say, creativity and innovation in business functions are the main sources of competitive advantage in all industries, and even more so in the luxury sectors, whereby the customer naturally expects a great deal of originality within what he perceives to be the aesthetic characteristics of the brand. He also expects the product to be recognizable and carry a part of the dream inherent in the brand.

At Louis Vuitton, for example, the seasonal variations made on the LV monogram (graffiti, cherries, new colors, new materials, embossed LV, etc.) have recently served these purposes and confirm Marc Jacobs’ creative talents and the opening of the brand to talented artists like Takashi Murakami.

Managing creative people has never been an easy task, even for themselves. In this chapter, after presenting a description of the nature of creative activities for a luxury brand, we will delve into the organizational matters related to it, with real-life examples of design structures and their underlying logic. This will show how product management interfaces with the creative work. We will also propose some insights into how the notion of brand aesthetics can help in solving some creative management issues, and finish the chapter by talking about the bridges that exist between brands’ creative activities and arts.

The Nature of Creative Activities

Most frequently, the creative process in the luxury business starts with a specific market segment being identified by those within the business or commercial part of the company. We refer to the people identifying the market opportunities as the prescribers because their function is similar to that of an architect prescribing the use of certain materials or a doctor recommending a certain cure. The prescribers in turn commission the product, giving the creative department a list of specifications regarding function and price. In U.S. and Anglo-Saxon companies, the marketing prescribers are known as merchandisers.

Figure 7.1 shows the typical sequence that a luxury product follows, from its concept to its presence in the distribution networks.

FIGURE 7.1 Luxury-Product Development Sequence

For the design of technical products, the prescriber can be the marketing or commercial department or the CEO, depending on the type of organization. There, the creation function would be split among product concept, design, and engineering. For reasons of simplification, we will follow the model shown in Figure 7.1, which is prevalent in luxury ready-to-wear or accessories, whereby the prescription emanates from the merchandising manager. (For the mass-market brands, it would come from the product manager.)

What is common to any typology of product or service is that the design/creation activities, always and systematically, follow a business idea.

It may sound banal, but the luxury industry is famous for believing too often that the designer’s genius transcends any market considerations. It may take all the long years of experience of Christian Lacroix in the LVMH group—from the creation of his maison de couture in 1987 until its sale to the Falic Group in 2005, a period in which a profitable income statement was never produced and where the cumulative losses reached more than €200 million—to prove that sheer and recognized creative talent needs to be framed by a competent business prescriber. Even the Falic brothers have not found the solution to transform the recognized talent of Christian Lacroix into an actually viable economic venture. In 2009, the fashion house was declared in default.

The merchandiser gathers all the market information from the company’s own retail and wholesale networks and from the competition, synthesizing this into a collection plan, which describes the number of groups, models, occasions of use, expected sales volumes, places, and prices at which the products can be sold.

The price indications determine the maximum cost at which the product can be manufactured because the retail and wholesale direct gross margin cannot fall below certain limits. This may not be a problem for high-margin brands, such as Louis Vuitton, which look for a 55 percent gross margin at retail and an absolute minimum of 30 percent at wholesale. Table 7.1 illustrates a simple price structure scheme. This would have a direct impact on the choice of the quality of leather for a handbag or of the fabric for a man’s suit, decisions typically made by the design team.

TABLE 7.1 Theoretical Price Structure for Luxury Ready-to-Wear and Leather Accessories

| Theoretical retail price | 320 | 100 |

| Minimum theoretical retail margin | 165 (55%) | 55 |

| Wholesale price | 155 | 45 |

| Minimum wholesale margin | 55 (35%) | 15.75 |

| Direct cost | 100 | 29.25 |

After receiving a specific assignment from the merchandising department, the design team, working closely with the company’s own prototyping department or with those of contracted manufacturers, will need to realize samples of the products.

The efficiency of the link between design and prototyping is a main source of competitive advantage for the luxury industry. Since most of today’s designers do not have the technical knowledge to transform their own concepts into real objects, the need for efficient modelisti is acute. Modelisti are handicraft professionals who are able to interpret the designs and ideas of the creative team, and are increasingly difficult to find. (Numerous great Italian shoe modelisti are spending their retirement as consultants for Chinese manufacturers.)

Gone is the Salvatore Ferragamo or the Cristobal Balenciaga who could construct their creations with their own hands. Today’s designers are visual, draw in 2D, and therefore need talented product developers.

When the prototyping activity is integrated into the company, we often see the design and development departments merged, as the competencies are complementary. The product development phase is not made of pure prototyping capabilities. In the case of shoes, for instance, the fit is a whole science, jealously protected, and rarely formalized, mastered by only a few individuals who come into play at the time of prototyping and preproduction of small series. The prototyping department is also responsible for integrating the production constraints, as illustrated in Figure 7.2.

FIGURE 7.2 Multiple Constraints Applied to the Creation Department

The creative function is the confluence point at which commercial, financial, image-related, technical, and logistical considerations come into play.

This leaves the most natural constraint within which the designers have to work: the respect for, and constant upgrade of, the brand identity. The invariant aesthetic components of the brand identity are still rarely formalized and it is left to the designers’ talent and sensibility to interpret the aesthetics of the brand, to keep it relevant with respect to fashion and longer-term social trends, and to ensure that it continues to reflect the brand values. A clearly formalized brand identity, expressing the invariable elements of what we have called the ethics and aesthetics of the brand, acts like a brand Bible and should be on every designer’s desk, from the office junior to the creative director.

Adding to the complexity of luxury creation is the sheer volume of creativity required of the design departments of multiproduct brands, such as Gucci, Vuitton, Loewe, Celine, Coach, Ralph Lauren, or Ferragamo. For a brand aiming at a lifestyle status, the minimum number of products to be presented in each collection every season is approximately as follows:

| Ladies’ ready-to-wear | 150 pieces |

| Men’s ready-to-wear | 100 pieces |

| Handbags | 50 pieces |

| Other leather goods | 100 pieces |

| Silk | 100 pieces |

| Total | 500 pieces |

For any model chosen for the season’s collection, we estimate there will be an average of three prototypes. This happens twice a year. That is, for any brand with ambitions to reach the lifestyle status, at least 3,000 products have to be conceived and prototyped every year.

To create this volume of products within a demanding time limit, functional and cultural constraints require rigorous coordination of resources.

Creation in the realm of service brands (restaurants, hotels, resorts, cruises, air travel, and so on) focuses more on the physical comfort provided to the customers, on spaces, and on communication.

Organization of the Creative Function

There are as many organizational models as there are luxury brands. A great deal depends on the number of product categories, the cultural approach to design, the simplicity of the brand aesthetics, the existence of strongly recognizable graphic codes, the designer’s reputation, the size of the company, and so on.

To get an idea of the diversity and the organizational importance of the design function, we’ll look at how this works at some leather-goods brands at different stages of their brand life cycle.

Leather-Goods Brands

Michel Vivien, chausseur à Paris, designs women’s shoes under his own name. He has them prototyped and manufactured by an Italian factory and sells them to the market himself through professional fairs. He has one design assistant, to whom he gives creative direction, and he does much of the creation himself. Not only does he directly control all creative activities, he manages all other functions as well. He probably sells fewer than fifty thousand pairs a year, and his turnover is probably around €1 million.

At Robert Clergerie, where, in 2004, the volume of shoes produced was several hundred thousand pairs and the turnover around €30 million, the prototype design group consisted of four people, and, as the company also had ambitions to move into the handbags and small leather-goods sectors, an external handbag designer was contracted. The company also used an external consultant as a creative director.

Christian Louboutin operates somewhere in between Michel Vivien and Robert Clergerie.

Loewe’s turnover at the end of the 1990s was in the region of a few hundred million euros from activities spanning leather goods, ready-to-wear, silk accessories, gift items, and fragrances for men and women. All products were designed in-house. The design function was spread across each of the four business units (leather goods, ladies’ ready-to-wear, men’s ready-to-wear, and fragrances) and comprised twenty people. In 1997, Narciso Rodriguez was hired to design the ladies’ ready-to-wear, and the CEO functioned as brand identity manager, coordinating all these creative talents as well as the communication and retail departments.

In the late 1990s, Bally was losing money, with a declining turnover of around €500 million. The sale of the company to the Texas Pacific Group, a U.S. private-equity fund, provided a good opportunity to restructure the brand to enable it to realize its ambition to become a lifestyle luxury brand reflecting perennial Swiss values.

The management started by clearly identifying the main culture and the competencies needed to reach its objectives. Figure 7.3 explains the rationale underlying the revised organizational chart.

FIGURE 7.3 Organizing by Competence

The business expertise is made up of merchants, who not only sell the goods through Bally’s own shops and wholesale customers, but are also responsible for prescribing the kind of collections they want (number of groups, models, prices, function, etc.). Under such a scheme, the sales and gross margins are clearly the merchandiser’s responsibility. He launches the development process and coordinates the various departments involved through establishing multifunctional teams. It is important to establish the rule that merchandisers never get involved in aesthetic matters, leaving 20 percent of the collection to be defined freely by the designers with no constraints whatsoever.

The logisticians produce and move goods. Decisions regarding suppliers, whose selection may be of strategic importance, are made in conjunction with designers and merchandisers. Then, all activities requiring a strong aesthetic sensibility, such as creation and communication, are regrouped.

In Bally, the organization chart for everyone involved in the creative activities in 2000 was structured along the lines shown in Figure 7.4.

FIGURE 7.4 Organization Chart of Design Function

The design and development functions were merged under a single responsibility to ensure a maximum fusion between 2D designs and prototyping. Editors at large—fashion reference personages, opinion leaders in the luxury world—were appointed in Paris, Hong Kong, and New York to keep the company advised on recent fashion trends, and on what the competition was doing, and to provide feedback on past and current collections. Not counting these or other outside staff, such as the PR offices and the design departments dedicated to the watch and golf shoe licenses, a total of thirty-one internal creative staff were involved in the process. The financial effort needed to sustain such a multiproduct brand strategy is enormous, but this is what the global lifestyle brands have to face.

Mass Market versus Luxury Brands

The examples drawn from the leather-goods industry highlight the numerous models that can coexist within the same sector. Looking at the luxury industry as a whole, the number of organizational solutions is almost equal to the number of brands, and this, we believe, stems from the difficulty of rationalizing the aesthetic dimension of the brands.

Within this apparent abundance of organizational solutions, we can identify two extreme and opposite models that both avoid the issues surrounding the management of intrinsic brand aesthetics without really solving them.

The first model is found in major luxury brands such as Dior or Chanel, where the aesthetic keys are handed to a talented and proven designer (John Galliano [until 2011] and Karl Lagerfeld, respectively) and the CEO has almost no power whatsoever in the creative function. Designer and CEO seldom meet except at cocktail parties, perhaps.

The second model belongs to mass-market brands like Gap, Zara, H&M, Celio, Springfield, and so on, where the design team (an army of anonymous individuals) works under the close supervision of the product manager, who imposes price and fashion constraints, and whereby creativity is reduced to following rigid commercial plans and what is currently hot in the market. This solution does not exclude specific initiatives with celebrities, such as the special fall 2006 collection orchestrated by H&M with Madonna. The product manager is frequently referred to as the collection manager or, as at Cortefiel, the buyer, which clearly reveals the main focus of their task. In this sector, the overall organization is quite simple. Besides the usual financial and HR functions, there will normally be three departments: the product department (merchandising, creation, sourcing), the communication department (advertising, PR, showroom management), and the retail/franchise department. The brand-identity tasks are spread across the organization chart.

The basic difference between the two solutions is in the importance given to the creativity function and thus to the decision-making power granted to the designer, which in turn reflects the brand’s basic culture and way of competing.

Each of these systems has created legends. The luxury model thrives on the geniality and talent of designers like Tom Ford at Gucci. It becomes much more difficult when the reigning designer does not have these exceptional talents. The second model has given birth to extraordinary success stories such as Zara or H&M in the past ten years—successes based essentially on good merchandising and on an extraordinary logistical capability that can reduce time-to-market to ten days.

Nonetheless, the optimal solution is more balanced, where the brand aesthetics are more coordinated and better oriented toward the constant reinforcing of the brand identity. How can these goals be achieved given the complex set of brand manifestations, all promoting the brand identity, performed by so many typologies of competencies? (See Figures 7.5 and 7.6.)

FIGURE 7.5 Brand Identity Manifestations—Different Competencies

FIGURE 7.6 Brand Identity Manifestations—Traditional Organizational Structures

Finally, who is in charge of a brand’s aesthetics? Who has the broad view necessary to span the range of brand manifestations and the power to act upon them?

The ultimate brand aesthetics manager can only be the CEO. He is in a position to really balance the sometimes competing logics of business and aesthetics and make the necessary tradeoffs between them. Not that we are asking him to be Giorgio Armani; such talents are given to very few. Neither are we suggesting that he be involved in actual design. Nevertheless, the CEO should be capable of working with both sides of the brain, and have proper aesthetic preparation and sensibility. In addition, a transparent and constructive attitude from all members of the top management team would help in producing an almost optimal aesthetic decision-making system.

Between the two extremes—creativity given free rein in the luxury industry, and a denial of creativity within the mass-market brands—there is room for more balanced organizational solutions whereby the respective logics informing the merchandising and creative processes can coexist and reinforce each other. The Bally solution presented earlier is, we believe, close to achieving that difficult balancing act.

Managing the Product

Having covered product design and development processes, organizational setup, and the interfaces between merchandising and design, it is appropriate, at this stage, to say something about product management.

Product management is knowing what to sell, where to sell it, at what price, and in which quantities, as well as monitoring the process from the concept stage through to distribution. The merchandiser has this responsibility.

In the case of the development of a series of goods, there are two key documents that govern the whole process: the collection plan and the collection calendar.

The Collection Plan

For each product category, the collection plan will ideally specify the following elements:

- The number of product groups, comprising those kept from the previous season and new products (a product group of a homogeneous set of products with similarities of material, form, occasion of use, and so on).

- The number of products for each group and of models for each product.

- The occasions of use of the various group products.

- The expected volume of each model per specific point of sale.

- The expected retail price and therefore the maximum direct cost of production. This will often include technical specifications for construction or the type of materials required because this will have a direct impact on the manufacturing costs and design choices.

The collection plan frequently provides supporting analysis based on previous sales statistics, competitors’ successes, and the respective positioning of the various groups.

Let’s take a real example from the men’s ready-to-wear world. For reasons of confidentiality, we will call this Spanish brand Don Juan. While the name has been changed, the data used here is drawn from the real world. The brand promotes an identity centered around its Spanish origins and tries to be trendy and up-to-date without being perceived as being excessively fashion forward.

A collection plan is necessary for each product category. We will concentrate on the one prepared for suits. We present a series of documents prepared by the merchandiser for the spring season 2007.

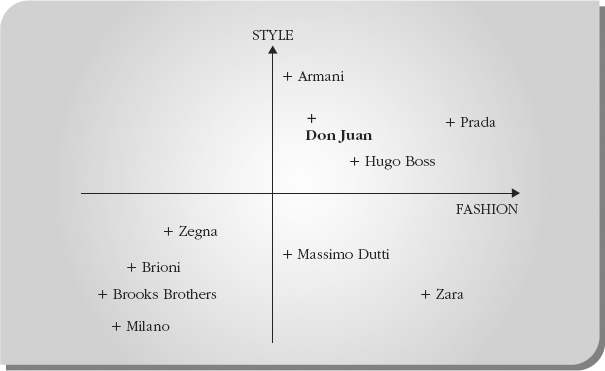

Figure 7.7 shows Don Juan’s position compared to the competition with respect to the basic dimensions of price and fashion content. It is important to monitor the market on a constant basis, and know where the brand wants to compete. The figure shows clearly that Don Juan is positioned between the mass brands competing on price and the global luxury leaders. Reinforcing this unique positioning in a field held traditionally by Italian, U.S., and British brands is the fact that it is the only brand daring to promote its Spanish roots as a main differentiating element of its brand identity.

FIGURE 7.7 Don Juan Suits Competitors Price/Fashion Map

The second document, shown in Figure 7.8, positions the brand with respect to its main competitors in terms of style and fashion. We said earlier that merchandisers were not supposed to be involved with a brand’s aesthetic considerations. Here, where the merchandiser defines the competitive frame into which the products have to be positioned (that is, the brand needs to have more stylistic content), this is not the same as defining and designing that style.

FIGURE 7.8 Don Juan Suits Competitors Style/Fashion

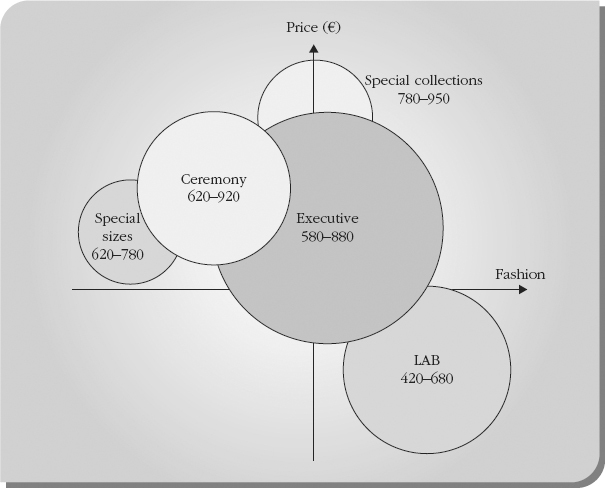

The third document, shown in Figure 7.9, maps the five groups of suits according to retail price and fashion.

FIGURE 7.9 Don Juan Suit Collection Structure

A general brief accompanies this, as shown in Table 7.2.

TABLE 7.2 Suit Collection Development Directions for Spring/Summer 2007

|

| EXECUTIVE collection: |

|

| LAB collection: |

|

A special design team with members of both parties is being set up.

Respect scrupulously the three sub-collection shipments to the stores.

As can be gathered from the real-life examples considered earlier, the merchandiser is the one really driving the whole development process of the collection, and needs to have the tools to ensure that all the departments involved are informed and coordinate with each other. There are other documents covering, for example, the expected volume of sales for each product and each individual model, by point of sale. This information, which can only be estimated, is probably the most difficult to quantify and the one with most financial consequences. Commitments on fabric orders are taken very early in the process and drive the business gross margins. This is the exercise in which the real professional merchandisers stand out.

The collection plan can vary in its format and in the information given, depending on the type of merchandise. It is the contractual document binding all the departments involved in the development process.

Note that the essentially strategic decision to add a new category of products—say, shoes—to the brand offer would be analyzed within the merchandising department.

The collection plan can take very different forms according to the product category. For a ladies’ shoe collection, there are likely to be lines instead of groups, classified by construction, occasion of use, specific soles, or materials. Each line will specify the desired retail price in the reference market, the heel height, and all the different materials that can be applied to it.

For a handbag collection, there are likely to be diagrams of groups positioned with respect to price and occasion of use, from the more formal to the more casual.

For a tie collection, things will be simpler. There will generally be two big categories separating printed silk from jacquard (woven), with a number of repeated and new patterns.

The Collection Calendar

The collection calendar formalizes the important moments in the collection development process agreed to by all the departments involved: ordering materials for samples and for production, intermediary meetings to review the design progress, final editing of the collection, ordering from the stores, and so on. It is the most shared common tool of all the departments involved in collection development.

Figure 7.10 illustrates a real example of a ladies’ shoe collection calendar, showing all the different steps involved. It is clear, for example, that prototype validation is a three-step process, with the line and model requiring approval before its final realization as a prototype.

FIGURE 7.10 Ladies’ Shoe Collection Calendar

The number of professional fairs attended by the designers and merchandisers is also indicated, as well as the regular involvement of the commercial department right up until the presentation of the sample collection to wholesale clients and store buyers.

The Product Empowerment Teams

Despite all the examples of monitoring tools and reports, more often than not the different cultures and specific operating objectives of different departments give rise to a lot of friction in the development process and, ultimately, to poor quality, late deliveries, higher costs, and higher prices.

To reduce the possibility of such problems, in 2000, Bally decided to launch what was called the PET (Product Empowerment Teams) project. The intention of the project was to focus people’s attention on the virtues of teamwork and to streamline the product development process.

A multifunctional team was created for each product division (men’s shoes, ladies’ shoes, men’s accessories, ladies’ accessories, men’s ready-to-wear, and ladies’ ready-to-wear). Each team, coordinated by the divisional merchandise manager, comprised the category head designers, the category developer, and a member of the supply management team, and each team worked in conjunction with retail operations and the wholesale, communication, information system, and finance departments. The focus of these teams was to make things happen quickly.

In order to give substance to this setup and make the team responsible for the performance of the division, we introduced financial incentives based on the objectives of the overall project, with the CEO directly monitoring team performance.

Table 7.3 shows the key performance indicators introduced.

TABLE 7.3 Performance Indicators for Product Empowerment Teams

| Performance | Indicators |

| Volume | Sales |

| Profitability | Sell-through net gross margin |

| Immobilized capital | Inventory turns (FG, WIP, RM) |

| Speed | On-time delivery Time to market Time for reassortment (replenishing retail stock during season) |

| Quality | Returns |

| Costs | Team operating costs |

| Team effectiveness | Initiatives and problem solving; number of interdepartmental conflicts Interfaces with retail, wholesale, communication Team cohesion, communication, atmosphere . . . fun |

Their efforts were worthwhile as they rapidly reduced the shipping delays, improved product quality, and remained within the planned prices.

It should be clear from this section that putting the right product in the right place, at the right time, at the right price, and in the right quantities is not a simple task.

Brand Aesthetics

In Chapter 6 we introduced a definition of brand aesthetics that differs from the usually accepted philosophical meaning of a discipline dealing with beauty. We took a semiotic approach, using the term to encompass all the brand elements belonging to the sensory world: the brand manifestations, which include not only the visual elements (forms, colors, light treatments, etc.), but also sound, taste, touch, and odor. We classified the manifestations into four aesthetic fields: products, communication, space, and behavior. The creative activities of a luxury brand operate at the center of the brand’s aesthetics. Is this relatively new notion really relevant for brand management?

Relevance of Brand Aesthetics

There are three main factors that establish the relevance of brand aesthetics.

First, there is a strong trend within society toward aestheticism, which is easily noticeable in the consumption of products and services. From the birth of design in the early 1950s, initially applied to small series or industrial machines, to the arrival of the likes of Ikea, Conran, Alessi, and Habitat, this phenomenon is clearly manifest. Today, design is everywhere. There are no successfully competitive products that have not been submitted to an aesthetic optimization. This is most evident in the extensive use of color in such objects as refrigerators, cell phones (which have risen in a few years to the status of fashion accessories), and personal computers.

Second, the simple fact that certain forms, colors, contrasts, or harmonies are more noticeable and easier to memorize than others, or trigger emotions in those exposed to them, proves the importance of aesthetics. Isn’t the objective of any creator and communicator to generate emotion and memories in the target customers? An advertisement showing a young lady with a nail in her forehead (Nell & Me) or monsters and mutants (Brema, Lee Cooper, Thierry Mugler’s fragrance, Alien, and so on) generates uneasiness, rejection, fear—all effects desired by their creators. There are proven statistical preferences for rectangles obeying the golden mean ratio. It has been medically proven that colors and light have a physiological and psychological impact. There are an infinite number of examples that show that mastering brand aesthetics can assist in managing a brand’s effects on its public.

The third aspect of the relevance of the notion of brand aesthetics is its ability to untie some tight corporate knots.

Issues Better Treated with the Notion of Brand Aesthetics

We are convinced that the notion of brand aesthetics can go a long way in helping to resolve issues related to creativity in brand organizations. In fact, the aesthetic notion allows us to tackle, with an innovative approach, communication, organizational, and cultural issues.

Communication Issues

The willingness to manage brand aesthetics in a systematic and rational way leads to some simple and immediate questions:

- Is the brand’s aesthetic (or a specific brand manifestation) contributing to communicate the brand ethics efficiently and therefore consolidating the brand identity?

- Is the aesthetic treatment of a specific brand manifestation serving the brand’s communication purpose (visibility, ease of memorization, special message to convey, specific emotion to generate, etc.) while remaining compatible with the brand aesthetics?

- Are the brand manifestations coherent among themselves?

Organization Issues

We saw earlier how difficulties in rationalizing the management of brand aesthetics can lead to two opposite and equally unsatisfactory organizational models: one giving full and unchallenged decision-making power to the designer; the other submitting the designer to the constraints of strict commercial rules. Rationalizing brand aesthetics would provide the necessary tools to allow a more fluid, balanced, and open rapport between all the direct and indirect participants in the process of creation.

Cultural Issues: The Missing Dictionary

Design personnel tend to hold the merchants in perfect contempt. For their part, the merchants do not hesitate to criticize the bad collection design when sales do not meet expectations. Meanwhile, the production and development people look on everyone as extremely frivolous and uneducated as to what a good product should be. These legitimate tensions often end up at a higher hierarchical level and affect the relationship between the head designer or creative director and the CEO or COO. In the confrontation between the manager—who lives among figures, statistics, budgets, consumer-behavior theories, board meetings, and financial analysts—and the creative designer—who is aware of the glamor of the position, sensitive to fashion and taste, mixing with the fashion elite and the press, and perhaps dreaming of imposing a specific aesthetic viewpoint on the world—the relationship is not always naturally easy and rarely allows for a rational and constructive dialogue.

“Why do you do that?” asks the CEO. “Because I feel it!” replies the designer.

The main reason for such irrational talk is that neither has really been educated in how to discuss brand aesthetics rationally and that very few tools exist that would allow them to establish a common vocabulary for doing so.

Given this, it is no surprise that most of the great designers have always had at their side a trusted person with whom they have had an exceptional symbiosis that has rendered unnecessary the need to explain. Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé are perhaps the best example of such a duo.

Possible Tools for Managing Brand Aesthetics

The analytical instruments introduced in Chapter 6—the brand hinge, the semiotic square, the communication chain, and the brand manifestations—are efficient at framing all the complex processes by which a brand produces meaning, but they are not adequate to tackle the plastic dimension (light, color, composition, lines, and so on) of brand aesthetics.

There are a number of tools that exist for managing the plastic dimension of the brand manifestations, used by artists and designers, that help in the choice of color and composition. We saw in Chapter 6 how entering into classical and baroque considerations helps in treating light, forms, and volumes and, above all, these aesthetic elements relate to specific brand ethics.

Authors such as Mazzalovo, who presents in his book, Estetica di marca,1 tools to manage the linear aspects of brand expression, and in general all the studies proposing instruments for management of brand plastic elements, can contribute to bringing the merchant and the creative cultures closer together.

Conclusion on Brand Aesthetics

Introducing the notion of brand aesthetics as a possible management tool presents a double challenge. The first of these challenges is to prove that the notion is powerful enough to introduce a new approach to solve real issues. The second revolves around the audacity of thinking that brand aesthetics can be managed. This is itself dependent on a basic axiom, a certain vision of the brand business world, a notion of corporate ethics that asserts that there is no such thing as a no-man’s-land within a company. Entrenched within such a notion is the idea that everybody must be able to explain the decisions they make and demonstrate how their choices are coherent with the company strategy and culture and how they make the brand more competitive.

Our considerations on brand aesthetics lead us naturally to the rich and complex relationships existing between brands and the arts.

Brands and the Arts

Given that both brands and artistic activities share a central core of creativity as their raison d’être, we may expect to find a lot of bridges between them.

We may think that the main difference between the activities of the commercial designer and the artist is that the latter generally does not have a business prescriber. While this may be so in most cases, we should not forget the role of the promoting gallery: The commercial dimension is never absent from artistic activities. There is a big overlap between the two worlds.

When we consider that paintings by Klimt, Picasso, and Van Gogh have reached prices well over €100 million at recent auctions, is there a real difference between the painter who has an exhibition every two years and sells his work through galleries and the ready-to-wear designer who stages a fashion show twice a year and sells his goods through monobrand and department stores? Is there a big difference between contemporary art fairs and fashion fairs?

Was there ever a time when the artist created independently of any money or power considerations? Artists, designers: Where is the border now that brands fully compete with movies, television, and literature in proposing new ways of dreaming? To analyze the convergence of the two worlds of art and brands, we first examine how each borrows from the other.

From Brands to Arts

Brands came to a rapid understanding of the benefits of being associated with artistic activities. Having a strong cultural dimension can never have an adverse effect on a brand’s identity. On the contrary, this is very much in the spirit of our times. When the affluence of cultural institutions, such as galleries and museums, has never been so great and the level of education is steadily increasing, for a brand not to develop a strong cultural dimension to its identity puts it at risk of losing competitive ground.

The designer’s work has a lot in common with the creative artistic process. Both the artist and the designer need to make decisions regarding shape, form, and color. The genuine ones have their own style and both have concerns, ideals of beauty, ethics, and values that they try to express through their work.

The associations between brands and art take several forms that can be classified according to the depth to which the brand’s involvement with art penetrates its brand identity. It may start from the merely episodic association of circumstance with a known artist or art piece, and progress to having an art dimension fully embedded in its brand identity.

From Episodic Associations to an Art-Based Brand Identity

Designers and communicators in the luxury field have long had recourse to artworks, either to compensate for their own wavering inspiration or simply in paying homage to the artist. Here are just a few examples of products or advertising that have taken their inspiration from works of art:

- Loewe scarf illustrated with a drawing and verses of Garcia Lorca; Etro scarves representing the Scala theater.

- Elena Miro’s advertisement reproducing Paul Gauguin’s Tahiti paintings using live models.

- A full-page Telefonica advertisement in the International Herald Tribune showing an Eduardo Chillida drawing.

- Vanessa Franklin’s work for Converse sport shoes in Wad magazine in 2005, in which paintings by Watteau, Boucher, and Ingres were scanned and superimposed with contemporary figures wearing Converse products.

- The Lanvin brand has always been closely associated with art since the Art Deco period, which was cherished by the brand founder, Jeanne Lanvin. The first page of its website is the interior of an opera theater and, like many other brands, it cultivates links with the cinema. Its men’s ready-to-wear summer 2006 collection was directly inspired by a Jean-Luc Godard film. Another advertising campaign made use of paintings by Ricardo Mosner, and drawings reminiscent of Matisse were used in advertising the Eclat d’Arpège fragrance.

- A new trend has recently seen special collections supposedly designed by artists. In April 2006, Tiffany announced a new partnership with internationally renowned architect Frank Gehry, who designed the extraordinary Bilbao Guggenheim museum, to create six exclusive jewelry collections. Similar initiatives are also in evidence outside the luxury world; when H&M offered a limited collection supposedly designed by Madonna in 2006, the products sold out on the first day they reached the stores.

- Cinema—the seventh art—has been the main source of cultural legitimacy for a lot of new brands. It conveys modernity, movement, and the public can identify easily with the famous actors, who have themselves become a resource much used by television and the Internet. Events such as the Cannes Film Festival are very coveted fashion platforms for the luxury ready-to-wear brands, with actresses commanding astronomical prices to wear a specific brand. Canali’s links to the Hollywood movie industry are promoted on its website, which lists the many recent movies in which its clothes have been worn. But the use of the cinema is by no means a recent phenomenon: Tod’s famous campaign showing Cary Grant, Steve McQueen, and Audrey Hepburn wearing its loafers went a long way toward establishing the brand as an iconic product.

- In the 1980s, Louis Vuitton launched a series of scarves designed by artists and designers such as Philippe Starck, Sol Le Witt, and James Rosenquist. However, since Marc Jacobs’ arrival in 1997, a stronger drive toward art in general has been evident. The first daring and very visible project was Stephen Sprouse’s graffiti on the traditional monogram canvas. The most prolific collaboration has been with Takashi Murakami, who worked for several seasons on new versions of the monogram and who himself is producing animations such as those presented at the Venice Biennale in 2003, and which are inspired by the brand. The creation of the exhibition room Espace in the Champs Elysées flagship store has been another major step in that direction. In 2008, it showed the photographs of Vanessa Beechcroft, and Alphabet Concept, letters made of nude models.

- One of the earliest and most common manifestations of the links between brands and the art world has been the cultural foundation: for example, La Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain was created in 1984, and is dedicated to promoting the development and awareness of all contemporary art forms, such as painting, video, design, photography, and fashion. Another example, though on a smaller scale, is the fundación Loewe. Created in 1988 with the objectives of encouraging the creation of music, drawing, and poetry among young people, it has instituted a coveted prize for poetry in the Castilian language. In fact, most of the major brands are involved informally in sponsoring artistic activities, such as Ferragamo sponsoring the restoration of an old painting.

- Some hotels have been pushing their association with the cultural world to a higher scale. The Guggenheim Hermitage Museum, designed by Pritzker Prize–winning architect Rem Koolhaas, is located at the Venetian Resort-Hotel-Casino. The museum opened in 2001 with the exhibition Masterpieces and Master Collectors: Impressionist and Early Modern Paintings. This is a very shrewd move for a service brand to link its identity with such mythical names and the highest standards in the cultural world. Past exhibitions have included Art Through the Ages: Masterpieces of Painting from Titian to Picasso, American Pop Icons, and A Century of Painting: From Renoir to Rothko—all art topics of relatively easy access for a nonspecialist public.

- Yves Saint Laurent’s own genius with colors and lines found a perfect challenge in matching the ephemeral nature of fashion to historical masters, paying homage to Mondrian (1965), Picasso (1979), Matisse (1981), Van Gogh (1988), and Warhol in his couture collections.

The utilization of art and artists by luxury brands has, in general, been quite successful and it is hard to see how such an association can harm a brand in any way. It helps attract the press and public attention, it reinvigorates brand creativity, it brings a new relevance to the brand when it is associated with current celebrities from the world of art, and it provides proof of the brand’s sensibility to aesthetics. Therefore, we are sure that the interest demonstrated by the brands toward the arts is bound to increase in the years to come.

In fact, we are now at the stage where certain brand creations are reaching art status. The New York Guggenheim museum was the first one to break that taboo when it organized an Armani exhibition in 2000. The 2003 exhibition of Guy Bourdin’s photographs from the 1970s advertising for Charles Jourdan are a good example of this change of status. Keep in mind that, fifteen years ago, the word fashion was almost obscene in art circles. The continuing rise of photography as an artistic activity has contributed to this change of perception, as well as the spread of fashion and design-related museums and exhibitions.

The similarities between brands and arts and their current convergence is very much a two-way street.

From Arts to Brands

Campbell Art versus Warhol Brand

Contemporary art has tried relentlessly to demystify the classical notion of artistic creation based on academicism, ideals of transcendental beauty, harmony, and so on. In the process, it has been instrumental in introducing into it elements that had never been incorporated before. Marcel Duchamp was a precursor to this when, in 1913, he presented a bicycle wheel on a stool as an artistic creation. He began incorporating into his artwork technical elements such as doorknobs, plastic bottles, and day-to-day objects. This was not completely new, however, as Picasso had already utilized the handlebar and saddle from a bicycle in representing a bull.

Duchamp refined his logic to incorporate the ready-made art pieces and the famous 1917 urinal. Here, the artistic position evolves into a purely editorial role, selecting objects from daily life and choosing the moment and place of the exhibition.

Is this so different from the way some of our current designers work, selecting from myriad prototypes made by their juniors the pieces that will appear on the catwalk? This extreme approach indeed leaves little room for real creativity.

Artistic activity reduced to the discovery of an original concept and leaning heavily on the techniques of provocation (all familiar words in the communication world) is something at which Andy Warhol was a master. He piled up Coke bottles, produced colored pictures of celebrities, and painted the famous Campbell soup can. The artwork reproduced the branded object without adding anything to it. Warhol himself recognized that there were no messages in his work, that he was a “commercial artist” and that, in fact, business was the most artistic activity of all. The difference between Warhol’s signed poster of the Campbell soup can and the actual product lies only in the discourse to be had about it. It is the art theory that makes the art piece.

Without knowing the theory, you cannot possibly know it is art. You need to be part of the avant-garde, this restricted group who know, hence the importance of communication in contemporary art.

If you do not know that a particular brand is hot, you are out of fashion. The artist is exploiting a relevant concept exactly as most brands are trying to do.

Postmodernism is crossed by a strong relativism. Everything is art, just like everything is communication.

Museum Business

Another taboo is disappearing. In the great rush to cash in on any little piece of reputation or notoriety that companies, institutions, or individuals may have gathered over time, the past ten years have witnessed an incredible fever of brand-extension activities that have led many brands to propose the most bizarre and illegitimate product offerings.

The great museums were among the first to open little souvenir shops within their own facilities, selling posters, art books, slides, and postcards to the cultural tourist. For institutions with names such as Le Louvre, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), and El Prado, the temptation to extend these activities is enormous, when all the competition is doing it and when it has no harmful effects on the customers’ brand perception.

Now, in downtown or airport boutiques we find an eclectic range of articles: impressionist ties, Van Gogh mouse pads, Mona Lisa T-shirts, Picasso refrigerator magnets, cubist Venetian glass pendants, and Velazquez aprons. It did not take long for business to realize the potential of these activities, and brand logic invaded arts when specialized brands—Museum Musei, for example, with its slogan, “The art from all over the world”—were specifically created to promote art-related articles. This is certainly a form of democratization of the arts, though it is not universally appreciated. After all, isn’t the single most obvious and most necessary determining characteristic of a museum the presence of objects within it?

The tangible museum boutique has also been made virtual through the Internet. Museumshop.com is a leader in offering thousands of products from hundreds of museums as well as its own inventions.

The artists themselves were among the instigators of such moves. Salvador Dali—whose strong commercial sensibility was such that his surrealist colleagues called him Avida Dollars, an anagram of his name—churned out prints and lithographs during his lifetime. His heirs allowed for the successful development of a sizable perfume and cosmetics business under his name. Paloma Picasso developed an accessory collection and, for the past few years, anybody can drive a Citroën model bearing the name of her father.

At the end of these converging processes of contemporary art proposing branded products as masterpieces, masterpieces glued all over with day-to-day consumer goods, and brands borrowing creative legitimacy from the artistic world, the frontier between art and brands has become blurred.

Indeed, the two worlds converge at a number of points:

- The nature of their creative activities.

- Their commercial aims.

- Their customers.

- The fact that contemporary art is becoming another element of lifestyle.

- The brand logic applied to their business in terms of differentiation, ethics, aesthetics, and the use of communication and distribution to serve their commercial objectives.

Today, brands and arts are indeed competing on the common ground of communication, trying to generate cash out of entertaining activities, offering both real and virtual experiences, trying to make people dream, and helping them escape reality.

It’s the same business, to the point where bridges between the two worlds may no longer be necessary: Their territories may now be completely contiguous, if not partly overlapping.

1. Gérald Mazzalovo, Estetica di marca, Franco Angeli, 2011.