MADEONEARTH

Report from the world of backyard technology

Photography by Mike Adair

Cranked-Up Creativity

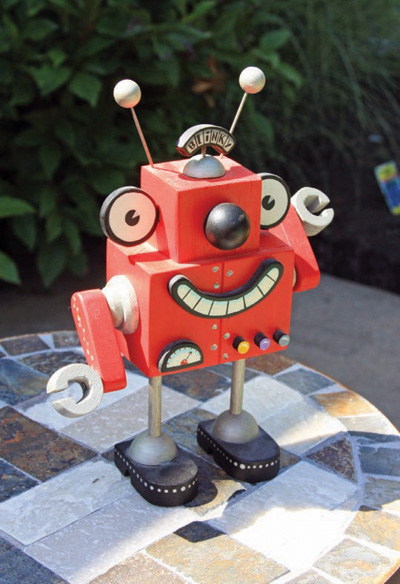

Mike Adair’s wife reports that he sleepwalks more when he’s in the middle of designing a toy. Adair, a 44-year-old artist from Overland Park, Kan., works at Hallmark. In his spare time, he builds brightly colored wooden crank toys in his basement workshop.

Most of his toys employ a hand crank that powers pulley wheels that create animation. The first crank toy he made, “The Debate,” depicts the visceral nature of human disagreement with humor and elegance.

The busts of two men face each other; the one smoking a pipe nods his head slowly, while the other, with a cigarette, shakes his head more vigorously. Using different sizes and shapes of pulley wheels and arm lengths, Adair can generate multiple speeds of action using a single crank.

Growing up in Southern California, Adair loved Disneyland’s animatronic attractions, counting America Sings and Country Bear Jamboree among his favorites: “Great examples of animatronic genius!” His family made a pilgrimage to the park every other year, and his parents raised money for the visits by participating in neighborhood craft shows.

“They worked all year making things to sell,” Adair remembers. “My dad cut out wood shapes and my mom did tole painting.” With his crafty parents and fascination with animatronics, Adair’s artistic inclinations were fed from a young age. As an adult, he visited London’s Cabaret Mechanical Theatre, which inspired him to begin building crank-animated toys.

His approach to coming up with toy ideas varies; he’s found it easiest to begin with the mechanics and build the concept afterward, but he’s learning to work both ways. “As my mental mechanism library increases, I’m able to come at it from the concept side and find the mechanism to carry it out,” he says.

In addition to building toys, Adair draws a comic for Boys’ Life magazine and hopes to make a popup book. For his next crank toy, he’s finishing a zombie cow tromping through a graveyard, called “Night of the Living Cud.” When the cow opens its decaying mouth, a canned “moo” will escape.

—Laura Cochrane

![]() Crank Animations in Action: mikeadair.com/Toys.htm

Crank Animations in Action: mikeadair.com/Toys.htm

Photograph by Eric Lawrence

Bright Idea

The chandelier that Eric Lawrence built from the molded styrofoam his new Apple computer came in looks like barracks that Frank Lloyd Wright would have designed for the Imperial Stormtroopers in Star Wars, he explains. He’s right.

Lawrence, 42, a web designer and former art student at the University of Texas, Austin, made the first Styrolight a few years ago. He’d just bought a new laptop, had all this styrofoam packaging lying around, and owed his nephew a Christmas present. He did the math.

“I like the way the foam diffuses light,” Lawrence says. “It’s keeping it out of the landfill, and I just like the shape.”

More lights followed. He tested different glues (settling on a hot glue gun) to connect the white blocks of foam and play with new shapes. He joined these to homemade aluminum frames of used bar and angle stock using two-part epoxy.

He bought all kinds of compact fluorescent light bulbs in search of the right color and brightness. LEDs weren’t simple and their color wasn’t as nice as with CFs. Finally, he found some 5-watt, dimmable fluorescent bulbs that emitted the perfect glow and burned as brightly as 20-watt incandescents, yet didn’t get dangerously hot.

“I’ve had [the 5-watt bulbs] on for 24 hours and can go grab a bulb in my hand,” he says.

In May 2009, Lawrence entered a 16-bulb, 35”×35” Styrolight into the Austin Design Within Reach showroom’s M+D+F furniture competition. When he won the sustainability prize, he took home a gift card, lots of attention, and endless bragging rights.

More commissions are coming his way, but he’s got a problem. “Unfortunately, Apple has quit using styrofoam, so my free source of materials no longer exists. I have enough left to build one big one.”

Be on the lookout for his next bright idea.

—Megan Mansell Williams

» Foam Chandeliers: styrolight.com

Photograph by Rob Ryan

Emotional Aquatics

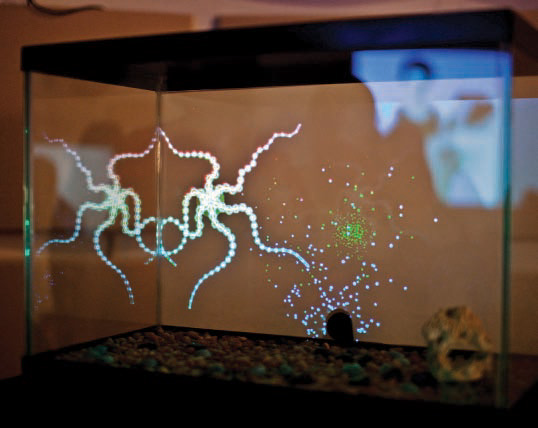

Inspired by Argentine writer Julio Cortázar’s short story of a man’s emotional obsession with aquarium life, Axolotl is about more than just an algorithmically enhanced animation displaying life-like traits from a fish tank. It’s also about the responses it gets.

NYU Interactive Telecommunications Program (ITP) grad student Eyal Ohana, 35, came up with the idea for Axolotl while brainstorming ways to portray life — and instigate reaction — through motion and form. Classmate Filippo Vanucci, 28, joined forces for its physical and interactive implementation. The result is a 3D audiovisual display attracting onlookers with a digitized squid-like creature that responds to facial recognition by simulating a sense of interaction and involvement.

To create Axolotl’s creature, Ohana and Vanucci utilized the open source programming language Processing 1.0. Each of the creature’s movements, such as undulating and contracting, are subject to physical forces like gravity and friction, but are also modified with unpredicted values. This generates non-repetitive, fluid motions similar to swimming, giving it a 3D appearance. “We’re still waiting for the creature to surprise us and do something really stupid we didn’t teach it,” says Ohana.

The creature is projected onto a fish tank from behind while an attached camera captures faces, streaming them into the computer where OpenCV-based software detects each face and its position.

“Metaphorically speaking,” says Ohana, “our creature can see.” It then reacts in one of two ways: shy but playfully curious, or totally terrified — a shrinking retreat that viewers seem to favor. Sound texture correlating to the creature’s movements adds ambiance. It was most recently shown at Brooklyn’s MediaLounge festival in June 2009.

Responses are diverse. Some see Axolotl as something funny and cute. Others try to trick it, hoping for a sudden reaction. But one thing’s certain: for eliciting interaction, it’s a success.

—Laura Kiniry

![]() Axolotl Video: eyalohana.com/axolotl

Axolotl Video: eyalohana.com/axolotl

Photography by Kevin Cyr

Camper Van Bicycle

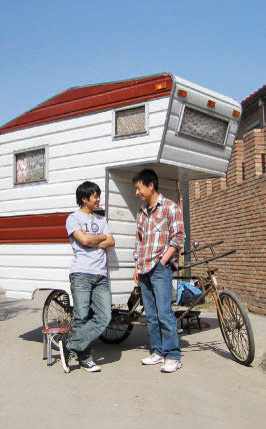

The connection between a three-wheeled bike, a shopping cart, and some paintings of old vans might not jump out to most people right away, but for Kevin Cyr the connection is obvious.

Cyr grew up in a Maine mill town whose economy is in decline. His vehicular art series, including the Camper Kart, Camper Bike, and paintings of vans, reflects his interest in the industrial working class.

Formerly a bike messenger in Boston, Cyr conceived of the Camper Bike while working in Beijing. In the Chinese capital, a large percentage of the populace use bicycles as a principal method of transportation and hauling, and only in recent years have people come to relate to cycling as a recreational activity.

“I was especially interested in three-wheeled bikes and how workers hauled gigantic loads on the bike’s flatbed,” Cyr explains. “I saw people carrying loads of building materials, large pieces of furniture, huge bags of styrofoam, really huge items that people in the West would use pickup trucks for.”

The Camper Bike is an amalgamation of something quintessentially Chinese (bike transportation) and something classically American (camping).

Inspired by Cormac McCarthy’s novel The Road, Cyr began sketching plans for the Camper Kart, essentially a pop-up camper affixed to a shopping cart. “I thought it was really interesting how McCarthy imagined the shopping cart as the most practical object in a post-apocalyptic time,” he says.

These “functional sculptures” exemplify Cyr’s nostalgic impulses. Cyr grew up with a 1977 Apache pop-up camper, and tried to limit the items he used to that period. After appropriating an abandoned shopping cart from Queens, he added canvas, vinyl, mesh, and accessories such as snaps, bungee cords, zippers, and velcro.

Cyr hopes the Kart will stimulate conversation about self-reliance, mobility, and shelter. He envisions it as a functioning sculpture emblematic of human perseverance.

—Thomas Walker Wilson

![]() More Work by Cyr: kevincyr.net

More Work by Cyr: kevincyr.net

Photograph courtesy of Carl Berg Projects

The Art of Fusion

In art world lingo, an “artist’s artist” is someone greatly admired by his or her peers, earning accolades from other artists that are oftentimes followed by critical and/or commercial success.

With his innovative use of plywood, fake fur, sawdust, foam, model-scale trees, and other familiar goods, Jared Pankin might inspire a new term: the “crafter’s artist.”

This is not to say that the art world hasn’t also embraced Pankin’s whimsically wild sculptures; his three solo exhibitions in Los Angeles got the stamp of approval from several contemporary art critics. But it’s this combination of art and craft that make Pankin’s chunky pseudo-naturescapes so compelling.

Pankin’s tableaux are both serious and light-hearted. Constructed from wood that is either found or easily available at the local hardware store, his works often resemble floating landscapes. These reference and refute nature at the same time, as if their maker’s knowledge of the organic stemmed from photographs or postcards, during an era when the natural world had been fully supplanted by the manmade, the constructed, and the built.

But before we take this apocalyptic scenario too seriously, Pankin — who actually lives and works in close proximity to the majestic Sequoia National Forest — steps in with tongue-in-cheek titles and visual puns. Hog Wild (2008) is a big hog’s head made from patched-together fake fur and mounted on the wall like a hunting trophy. In Half Knot (2008), the front of a fox is completed by a chunk of dark wood in back, which doubles as a tail that eases effortlessly into a tree, stretching into the air above the animal as it teeters on a tower that seems part Tinkertoy and part craggy mountainside.

The environment is endangered, but Pankin isn’t waiting for it to disappear. Instead, he leaps headfirst into a sea of imaginative re-envisioning, creating neither replica nor homage to nature, but a playful fusion of the organic and the manmade, of art and craft.

—Annie Buckley

» More Pankin: makezine.com/go/pankin

Photography by Andrew Chase

Mechanimals Menagerie

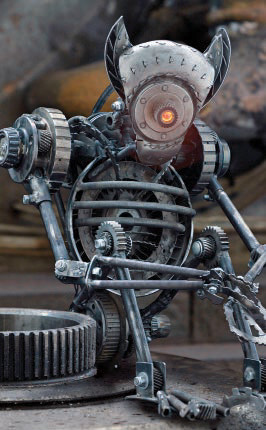

In the imaginary mechanical underworld they inhabit, the elephant is a bulldozer, the giraffe is a crane, the cheetah a courier. In real life, the mechanical animals, or “mechanimals,” are the work of Salt Lake City, Utah, sculptor and commercial photographer Andrew Chase, who welded them together from sheet metal, iron pipe, and used car parts.

Chase, 42, began building the mechanical beasts in 2004 as props for a children’s book he wrote and photographed, Timmy. In the as-yet-unpublished story, a robot leaves his subterranean home to explore the surface. Chase took the background photos first, then matched the lighting, and finally positioned the mechanimals in his studio, later merging the images via Photoshop.

About his use of old transmission gears and bearings, Chase says, “It is partly a financial decision — they’re free.” But beyond that, they look neat. “Things that are made for a purpose have a certain elegance about them,” he says. “If I didn’t incorporate gears and bearings, the animals wouldn’t look as industrial and purposeful. They’d look less useful.”

Each sculpture starts with what Chase considers the hardest part: the eyes and head. From there he creates the torso and legs, giving each limb fully functional joints, albeit in a single plane. Due to the nature of Chase’s car-parts medium, the animals are all roughly the same size, averaging about 3 feet tall and weighing up to 125 pounds.

Chase’s mechanical elephant went through four iterations before taking on its pachyderm form. “On my second try the body was better but still wrong. It looked too much like a dog. Finally, I swallowed my pride and found some good reference material,” he admits. Now he relies heavily on photos and animal anatomy drawings.

“Each beasty takes between 60 to 80 hours,” says Chase. Much of that time is spent scrubbing parts cocooned in sedimentary layers of oil, grease, and dirt. “The cleanup sucks,” he says. “It’s horrible.”

—Ian Dille

» Chase’s Mechanimals: makezine.com/go/mechanimals

Photo courtesy of Rob Bell

In the Zome

The next big thing in construction may follow the example of the car industry — it might be all about the hybrid.

Rob Bell and Patricia Algara created their own hybrid structure, a DIY greenhouse they call the Algarden Zome. A Zome is a “sort of hybridized structure; part geodesic dome, part jewel, and part yurt,” explains Bell, who used the same concept to make a tent-like “Zomecile” that won accolades at the Austin Maker Faire in 2007.

By salvaging the plastic sheeting from an old collapsed greenhouse and making good use of their ShopBot CNC router, this software engineer and landscape architect duo were able to inexpensively build a replicable design. They based the structure on a class of polyhedra known as zonohedra.

“While a dome will tend to resemble a sphere, a Zome will resemble a jewel,” explains Bell, who works as a designer and fabricator when he’s not writing software.

Designed as a model for building similar structures, the Algarden Zome designs are open source and available free from the Google 3D Warehouse.

While the goal was to create a structure that anyone with access to a CNC tool could easily make and assemble, that’s not to say the initial build was a piece of cake. The Algarden Zome took 80 hours of CNC cutting and assembly, then friends were recruited for more days of site prep, painting, and assembly.

The biggest difficulty Bell and Algara had was managing the many distinct but similar-looking parts. The Algarden Zome consists of 84 individual panels, each built from two separate frames encasing translucent plastic sheeting. The 168 panel frames are actually made from 1,344 individual pieces cut from marine-grade birch plywood, and keeping all these pieces organized was challenging.

The unique building pattern is extremely versatile, and its jewel-like symmetry makes it a nice fit for yoga studios and guest cottages, Bell points out: “The organic design is very aesthetically harmonious and spiritually resonant.”

—Bruce Stewart

» More Zome Photos: makezine.com/go/zome