Chapter One

TQM: An Overview and the Role of Management

B. G. Dale, M. Papalexi, D. Bamford A. van der Wiele

In today's global competitive marketplace the demands of customers are gradually increasing as they require improved quality of services and products. Also, in some markets there is an increasing supply of competitively priced products and services from low labour cost countries such as those in the Far East, the former Eastern bloc, China, Vietnam and India. TQM and Strategic Process Improvement does not appear to have reached maturity in many BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, China) economies (Moosa and Cardak 2006). This presents an opportunity, as well as a challenge, for TQM practitioners. Continuous improvement in total business activities with a focus on the customer throughout the entire organization and an emphasis on flexibility and quality is one of the main means by which companies face up to these competitive threats. For this reason, many organizations are looking for quality management and strategic process improvement in order to survive in increasingly aggressive markets and maintain a competitive edge over their rivals (Bamford et al. 2015). As a result of the efforts made by organizations to respond to these marketplace demands the quality of products, services and processes has increased considerably during the last two decades. Oakland (2014) states that:

Total Quality has always been a key strategic factor for business success but it is now more than ever required to compete successfully in the global markets of the twenty-first century. Having said this, it should be pointed out that in many markets today, quality is narrowly defined as the reliability of products and services. It is not considered as a competitive weapon any more but as a given requirement; and is considered an entry-level characteristic in the marketplace. These days, many organizations have had experiences with working on the transformation towards total quality management (TQM) and/or strategic process improvement and this is coupled with its spread, from the manufacturing to the service sector and on to public services. In addition, new domains present themselves. For example, according to Bamford et al. (2016) achieving and maintaining a quality culture is complex across all industrial sectors but amplified in off-field sporting operations due to particular industry characteristics (Smith and Stewart 2010). For example, operating rules and regulations are often imposed on sporting venues by external parties, the outcome of a sporting tournament is uncertain, fans are both producers and consumers of the sporting experience and sporting rivals must collaborate to organize competitive events (Chadwick 2009, 2011; Stewart and Smith 1999). It is these industry characteristics that provide a backdrop of environmental uncertainty for off-field sporting operations and make quality management in this context a particularly interesting focus for further examination (Bamford et al. ). But what is TQM? In simple terms, it is the mutual co-operation of everyone in an organization and associated business processes to produce value-for-money products and services which meet and, hopefully, exceed the needs and expectations of customers. TQM and strategic process improvement are ever-evolving practices of doing business in a bid to develop methods and processes that cannot be imitated by competitors. This chapter provides an overview of TQM and introduces the reader to the subject. It opens by examining the different interpretations that are placed on the term ‘quality’. It then examines why quality has grown in importance during the last decades. The evolution of quality management (‘Co-ordinated activities to direct and control an organization with regard to quality’: ISO 9001 2015) is described through the stages of inspection, quality control, quality assurance and onwards to TQM. In presenting the details of this evolution, the drawbacks of a detection-based approach to quality are compared to the recommended approach of prevention. Having described these stages the chapter examines the key elements of TQM – commitment and leadership of the chief executive officer (CEO), planning and organization, using tools and techniques, education and training, employee involvement, teamwork, measurement and feedback, and cultural change. The chapter concludes by presenting a summary of the points which organizations need to keep in mind when developing and advancing TQM. This is done under the broad groupings of organizing, systems and techniques, measurement and feedback, and changing the culture. ‘Quality’ has a variety of definitions, interpretations and uses. Today, in a variety of situations, it is perhaps an over-used word. For example, when a case is being made for extra funding and resources, to prevent a reduction in funding, or to keep a unit in operation and in trying to emphasize excellence, just count the number of times the word ‘quality’ is used in the argument or presentation. Quality as a concept is quite difficult for many people to understand, and much confusion and myth surround it. In a linguistic sense, quality originates from the Latin word ‘qualis’ which means ‘such as the thing really is’. There is an international definition of quality: ‘the degree to which a set of inherent characteristics fulfils requirements’ (ISO 9001 2015). However, in today's business world there is no single accepted definition of quality. Irrespective of the context in which it is used, it is usually meant to distinguish one organization, event, product, service, process, person, result, action, or communication from another. Preventing confusion and ensuring that everyone in an organization is focused on the same objectives, there should be an agreed definition of quality. For example, BetzDearborn Inc. defines quality as: ‘That which gives complete customer satisfaction’, and Rank Xerox (UK) as ‘Providing our customers, internal and external, with products and services that fully satisfy their negotiated requirements’. North West Water Ltd use the term ‘business quality’ and define this as:

Understanding and then satisfying customer requirements in order to improve our business results. Continuously improving our behaviour and attitudes as well as our processes, products and services. Ensuring that a customer focus is visible in all that we do. There are a number of ways or senses in which quality may be defined, some being broader than others but they all can be boiled down to either meeting requirements and specifications or satisfying and delighting the customer. When the word quality is used in a qualitative way, it is usually in a non-technical situation. ISO 9001(2015) says that ‘the term “quality” can be used with adjectives such as poor, good or excellent'. Some examples related to this are:

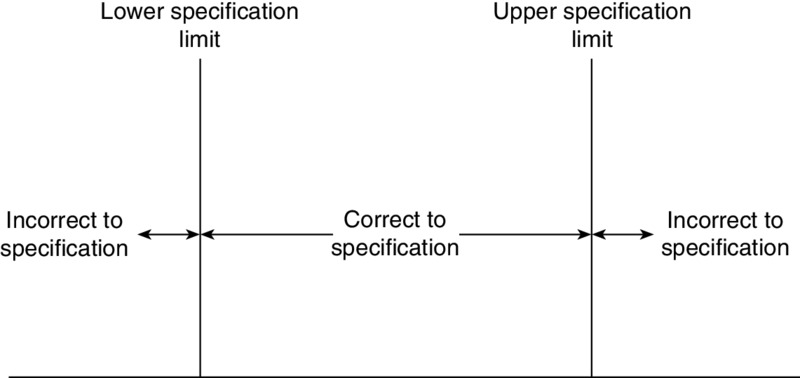

It is frequently found that in such cases of ‘quality speak’ the context in which the word quality is used is highly subjective and in its strictest sense is being misused. For example, there is more than one high street shop which trades under the name of ‘Quality Seconds’, and some even advertise under the banner of ‘Top Quality Seconds’. There is even a company with the advertising slogan ‘Quality Part-Worn Tyres’ on the side of its vans. The traditional quantitative term which is still used in some situations is acceptable quality level (AQL). This is defined in ISO/NWIP 3951-2 (2010) as: ‘the quality level that is the worst tolerable process fraction nonconforming when a continuing series of lots is submitted for acceptance sampling’. This is when quality is paradoxically defined in terms of non-conforming parts per hundred (i.e. some defined degree of imperfection). An AQL is often imposed by a customer on its supplier in relation to a particular contract. In this type of situation the customer will inspect the incoming batch according to the appropriate sampling scheme. If more than the allowed number of defects is found in the sample the entire batch is returned to the supplier or the supplier can, at the request of the customer, sort out the conforming from non-conforming product on the customer's site. The employment of an AQL is also used by some companies under the mistaken belief that trying to eliminate all defects is too costly. The setting of an AQL by a company can work against a ‘right first time’ mentality in its people as it appears to condone the production and delivery of nonconforming parts or services, suggesting that errors are acceptable to the organization. It is tantamount to planning for failure. For example, take a final product which is made up of 3,000 parts: if the standard set is a 1 per cent AQL, this would mean that the product is planned to contain 30 non-conforming parts. In reality there are likely to be many more because of the vagaries of the sampling used in the plan or scheme, whereby acceptance or rejection of the batch of product is decided. Another example of a quantitative measure is to measure processes using sigmas (a sigma is a statistical indication of variation) and defects per million opportunities (DPMO). A sigma is essentially a measuring device that is an indication of how good a product or service is. The higher the sigma value the lower the number of defects. For example, 3 sigma equals 66,807 DPMO, while 6 sigma equals 3.4 DPMO (these values assume a normal distribution with a process shift of 1.5 sigma). The sigma level is a means of calibrating performance in relation to customer needs. Six Sigma (a quality improvement framework) has used sigmas to improve productivity and quality and reducing costs. Six Sigma is the pursuit of perfection and represents a complete way of tackling process improvement from a quantitative approach, involving many of the concepts, systems, tools and techniques described in this book. The Six Sigma concept is currently very popular as a business improvement approach. The key features include a significant training commitment in statistics and statistical tools; problem-solving methodology and framework; project management; a team-based project environment; people who can successfully carry out improvement projects (these are known as black belts and green belts, based on the martial arts hierarchy); leaders (master black belts); and project champions. Figure 1.1 presents the inside/outside specification dilemma; only the product or service dimensions that are within the design specification or tolerance limits can be considered acceptable. The difference between what is considered to be just inside or just outside the specification is marginal. It may also be questioned whether this step change between pass and fail has any scientific basis and validity. Figure 1.1 The inside/outside specification dilemma Designers often establish specification limits without sufficient knowledge of the process by which the product and/or service is to be produced/delivered and its capability. It is often the case that designers cannot agree amongst themselves about the tolerances/specification to be allocated, and they tend to establish a tighter tolerance than is justified to provide safeguards and protect themselves. In many situations there is inadequate communication on this matter between the design and operation functions. Fortunately, this is changing with the increasing use of simultaneous or concurrent engineering. The main issue of working to the specification limits is that it frequently leads to tolerance stack-up; for example, in a manufacturing situation parts may not fit together correctly at the assembly stage. This is especially the case when one part that is just inside the lower specification limit is assembled to one that is just inside the upper specification. If the process is controlled such that a part is produced around the nominal or a target dimension with limited variation (see Figure 1.2), this problem does not occur and the correctness of fit and smooth operation of the final assembly and/or end product are enhanced. Figure 1.2 Design tolerance and process variation relationship The idea of reducing the variation of part characteristics and process parameters so that they are centred around a target value can be attributed to Taguchi (1986). He writes that the quality of a product is the (minimum) loss imparted by the product to the society from the time the product is shipped. Among the losses he includes time and money spent by customers; consumers' dissatisfaction; warranty costs; repair costs; wasted natural resources; loss of reputation; and, ultimately, loss of market share. The relationship of design specification and variation of the process can be quantified by a capability index, for example, Cp, which is a process potential capability index:

This definition is attributed to Crosby (1979). He believed that quality is not comparative and that there is no such thing as high quality or low quality, or quality in terms of goodness, feel, excellence and luxury. In other words, quality is an attribute (a characteristic which by comparison to a standard or reference point, is judged to be correct or incorrect) not a variable (a characteristic which is measurable). Crosby made the point that the requirements are all the actions required to produce a product and/or deliver a service that meets the customer's expectations, and that it is management's responsibility to ensure that adequate requirements are created and specified within the organization. Juran (1988) was the first to use this definition of quality. He classifies ‘fitness for purpose/use’ into the categories of: quality of design, quality of conformance, abilities and field service. Focusing on fitness for use helps to prevent the over-specification of products and services. Overspecification can add greatly to costs and tends to militate against a right-first-time performance. Satisfying customers and creating customer enthusiasm through understanding their needs and future requirements is the crux of TQM and strategic process improvement. TQM is all about customer orientation and many company missions are based entirely on satisfying customer perceptions. Customer requirements for quality are increasing and becoming stricter. There are increasing levels of intolerance of poor quality goods and services and low levels of customer service and care. In most situations customers have a choice: they are not willing to jeopardize their own business interest out of loyalty to a supplier who does not perform as they expected; they will simply go to a competitor. In the public sector the customer may not have this choice; however, they can go to litigation, write letters of complaint, cause disruption, and use elections to vote officials out of office. Superior-performing organizations go beyond satisfying their customers: they emphasize the need to delight them by giving them more than what is required in the contract. These organizations create a total experience for their customers, which is unique in relation to the offerings of competitors (which is called ‘the experience economy’, see Pine and Gilmore 2011). The wisdom of this can be clearly understood considering the situation where a supplier has given more than the customer expected (for example, an extra glass of wine on an aircraft; a sales assistant going out of their way to be courteous and helpful and providing very detailed information) and the warm feelings generated by this type of action. A customer-focused organization also puts considerable effort into anticipating the future expectations of its customers (i.e. surprising quality), by working with them in long-term relationships, helping them to define their future needs and expectations. They aim to build quality into the product, service, system and/or process as upstream as is practicable. Excitement and loyalty are the words used to describe this situation. A mechanism for facilitating a continuous two-way flow of information between themselves and their customers is considered necessary. There is also a variety of means available to companies for them to assess issues such as:

Organizations tend to focus on increasing the level of contact with the customer. These ‘moments of truth’ (Carlzon 1987; also see Fatma 2014) occur far more frequently in commerce, public organizations, the Civil Service and service-type situations than in manufacturing organizations. They use the following practices to increase the level of customer contact:

Customer complaints are one indication of customer satisfaction, and many organizations have a number of metrics measuring such complaints. BS ISO 10002 (2014) provides guidance on how to develop an effective complaints management system in order to analyse and use complaints effectively. The rationale is that managing complaints in a positive manner can enhance customer perceptions of an organization, increase lifetime sales and values and provide valuable market intelligence. To answer this question, just consider the unsatisfactory examples of product and/or quality service that you, the reader, have experienced, the bad feelings it gave, the resulting actions taken and the people you told about the experience and the outcome. Sargeant et al. (2012), based on a range of studies carried out by TARP (Technical Assistance Research Programs), outline two arguments that are effective in selling quality to senior management. First, quality and service improvements can be directly and logically linked to enhanced revenue within one's own company; and secondly, higher quality allows companies to obtain higher margins. The following extracts some quantitative evidence in relation to these arguments:

In the 30-plus pages of ‘Discoveries 2013’, the American Society for Quality (ASQ) presented a report on the current use of core quality practices. The report included aspects of quality governance and management, outcomes and measures, competencies/training and culture. A selection of results, as highlighted by Hill (2014), is outlined below:

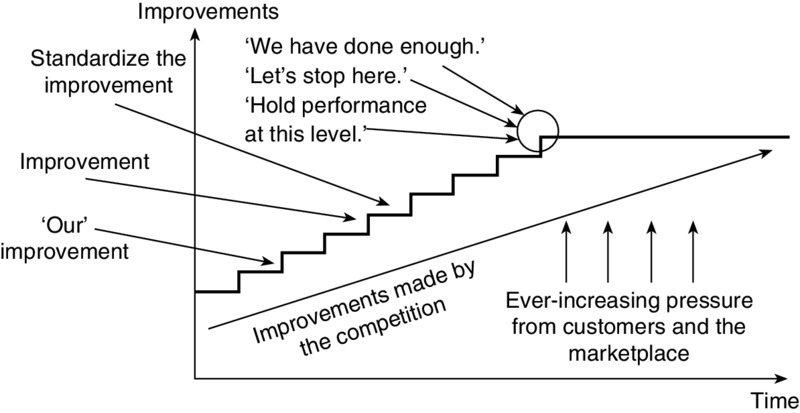

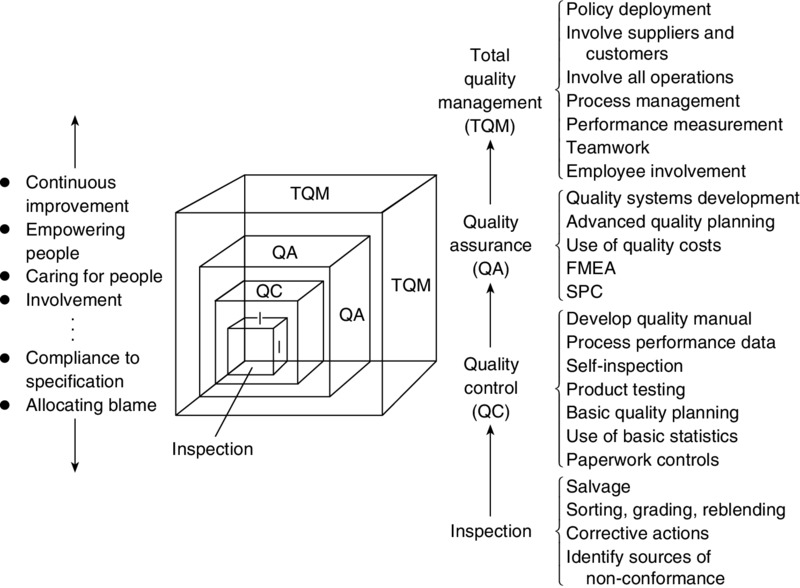

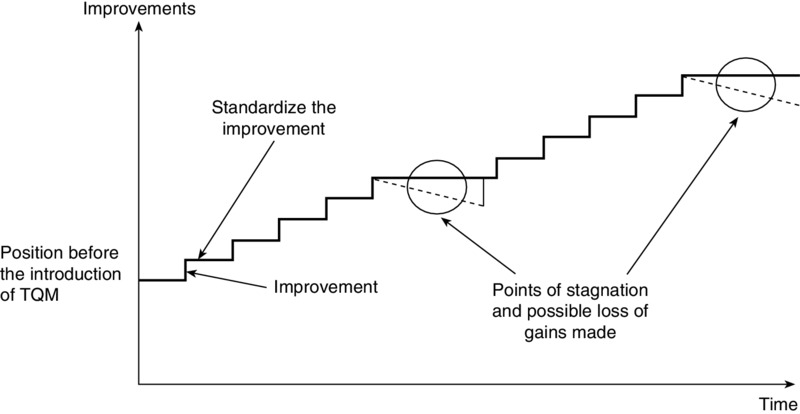

It is difficult to determine the value of these results without having understood the customers' perception on quality. An order, contract or customer which is lost on the grounds of non-conforming product and/or service quality is much harder to regain than one lost on price or delivery terms. In a number of cases the customer could be lost for ever; in simple terms the organization has been outsold by the competition. If you have any doubt about the truth of this statement just consider the number of organizations that have gone out of business or lost a significant share of a market, and consider the reported reasons for them getting into that position. Quality is one of the factors that is not negotiable and in today's business world the penalties for unsatisfactory product quality and poor service are likely to be punitive. There are a number of single-focus business initiatives that an organization may deploy to increase profit. TQM and strategic process improvement encompass not only product, service and process improvements but also those relating to costs and productivity and to people involvement and development. A number of surveys show that customers are willing to pay more for improved quality of products and services. For example, in 2015, according to a survey by Hot Telecom, 56 per cent of respondents in Asia Pacific would pay extra for better coverage and faster downloads, 83 per cent of them seeking tailored offers based on their usage patterns (Waring 2015). In a similar vein, a study conducted by American Express on Australian consumers found that 73% of respondents were willing to pay more for good products and services (Philp 2011). Managers sometimes say that they do not have the time and resources to ensure that product and/or service quality is done right the first time. They go on to argue that if their people concentrate on planning for quality then they will be losing valuable operational time, and as a consequence output will be lost and costs will rise. Despite this argument, management and their staff will make the time to rework the product and service a second or even a third time, and spend considerable time and organizational resources on corrective action and placating customers who have been affected by the non-conformances. Remember ‘Murphy's Law’ – ‘There is never time to do it right but always time to do it once more.’ Kano et al. (1983) carried out an examination of 26 companies which won the Deming Application Prize (this is a prize awarded to companies for their effective implementation of company-wide quality control; for details see Chapter 12). Between 1961 and 1980 they found that the financial performance of these companies in terms of earning rate, productivity, growth rate, liquidity, and net worth was above the average for their industries. According to Lee and Lee (2013), 223 companies have won the Deming Application Prize as of 2011. There are 95 award winners of the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award (MBNQA) from 1988 to 2011 in different industry sectors, such as manufacturing, health care, service, education and small business. This programme was established to enhance the competitiveness of US businesses based on the seven criteria: leadership; strategic planning; customer focus; measurement, analysis and knowledge management; workforce focus; operations focus; and results (NIST 2011). Similarly, the European Foundation Quality Management (EFQM) Excellence Model, which was developed based on MBNQA, has been used by over 20,000 organizations across Europe (Lee and Lee 2013). The Canada Awards for Excellence, which was developed based on the National Quality Institute's Framework for Organizational Excellence, has been designed to support continuous quality improvement for non-profit organizations, such as government, education, and health care (Evans and Lindsay 2009). Lee and Lee (2013) concluded that there are many organizations award winners in the manufacturing and service sectors. In particular, they found that the most commonly used quality awards in the world, based on number of quality awards given, are as follows: EFQM (42.1%); MBNQA (25.2%); the Deming Award (7.5%); and other quality awards (25.2%). Based on a variety of companies, industries and situations, the cost of quality (or to be more precise the cost of not getting it right the first time) ranges from 5 to 25 per cent of an organization's annual sales turnover in manufacturing or annual operating costs in service-type situations; see Dale and Plunkett (1999) for details. An organization should compare its profit-to-sales turnover ratio to that of its quality costs-to-sales turnover ratio in order to gain an indication of the importance of product and service quality to corporate profitability. Chiarini (2015) examined the impact of the ISO 9001 non-conformity process on the cost of poor quality in different sectors, including chemical, pharmaceutical, mechanical, food, ceramic and steel. He found that the ISO 9001 non-conformity process has the same impact on these six different sectors, highlighting that the reduction in cost of poor quality was no more than 27.14 per cent. He suggested that other important factors could reduce the total cost of poor quality, including the adoption of improvement techniques such as: Six Sigma and TQM. In today's markets, customer requirements are becoming increasingly more rigorous and their expectations of the product and/or service in terms of conformance, reliability, dependability, durability, interchangeability, performance, features, appearance, serviceability, user-friendliness, safety, and environmental friendliness, is also increasing. These days many superior-performing companies talk in terms of being ‘customer-obsessed’. At the same time, it is likely that the competition will also be improving and, in addition, new and low-cost competitors may emerge in the marketplace. Consequently there is a need for continuous improvement in all operations of a business, involving everyone in the company. The organization that claims that it has achieved TQM and strategic process improvement will be overtaken by the competition. Once the process of continuous improvement has been halted, under the mistaken belief that TQM has been achieved, it is much harder to restart and gain the initiative on the competition (see Figure 1.3). This is why TQM should always be referred to as a process and not a programme. Figure 1.3 Quality improvement: a continuous process Quality is a way of organizational and everyday life. It is a way of doing business, living and conducting one's personal affairs. Quality is driven by a person's own internal mechanisms – ‘heart and soul’, ‘personal beliefs’. Belief in it can be likened to that of people who follow a religious faith. Companies like Toyota emphasize strongly the need for the commitment of all employees to managing and improving quality, which is an essential part of the famous Toyota Production System (Kull et al. 2014). An organization committed to quality needs quality of working life of its people in terms of participation, involvement and development and quality of its systems, processes and products. Systems for improving and managing quality have evolved rapidly in recent years. During the last two decades or so simple inspection activities have been replaced or supplemented by quality control, quality assurance has been developed and refined, and now many companies, using a process of continuous and company-wide improvement, are working towards TQM and strategic process improvement. In this progression, four fairly discrete stages can be identified: inspection, quality control, quality assurance and total quality management; it should be noted that the terms are used here to indicate levels in a hierarchical progression of quality management (Figure 1.4). British and International Standards definitions of these terms are given to provide the reader with some understanding, but the discussion and examination are not restricted by these definitions. Figure 1.4 The four levels in the evolution of TQM Conformity evaluation by observation and judgement accompanied as appropriate by measurement, testing or gauging. (ISO 9000 2015). At one time inspection was thought to be the only way of ensuring quality, the ‘degree to which a set of inherent characteristics fulfils requirements’ (ISO 9000 2015). Under a simple inspection-based system, one or more characteristics of a product, service or activity are examined, measured, tested, or assessed and compared with specified requirements to assess conformity with a specification or performance standard. In a manufacturing environment the system is applied to incoming goods and materials, manufactured components and assemblies at appropriate points in the process and before finished goods are passed into the warehouse. In service, commercial and public service-type situations the system is also applied at key points, sometimes called appraisal points, in the production and delivery processes. The inspection activity is, in the main, carried out by dedicated staff employed specifically for the purpose, or by self-inspection of those responsible for a process. Materials, components, paperwork, forms, products and goods which do not conform to specification may be scrapped, reworked, modified or passed on concession. In some cases inspection is used to grade the finished product as, for example, in the production of cultured pearls. The system is an after-the-event screening process with no prevention content other than, perhaps, identification of suppliers, operations, or workers, who are producing non-conforming products/services. There is an emphasis on reactive quick-fix corrective actions and the thinking is department-based. Simple inspection-based systems are usually wholly in-house and do not directly involve suppliers or customers in any integrated way. Part of quality management focused on fulfilling quality requirements. (ISO 9000 2015) Under a system of quality control one might expect, for example, to find in place detailed product and performance specifications, a paperwork and procedures control system, raw material and intermediate-stage product-testing and reporting activities, logging of elementary process performance data, and feedback of process information to appropriate personnel and suppliers. With quality control there will have been some development from the basic inspection activity in terms of sophistication of methods and systems, self-inspection by approved operators, use of information and the tools and techniques which are employed. While the main mechanism for preventing off-specification products and services from being delivered to customers is screening inspection, quality control measures lead to greater process control and a lower incidence of non-conformance. Those organizations whose approach to the management of quality is based on inspection and quality control are operating in a detection-type mode (i.e. finding and fixing mistakes). In a detection or ‘firefighting’ environment, the emphasis is on the product, procedures and/or service deliverables and the downstream producing and delivery processes; it is about getting rid of the bad things after they have taken place. Considerable effort is expended on after-the-event inspecting, troubleshooting, checking, and testing of the product and/or service and providing reactive ‘quick fixes’ in a bid to ensure that only conforming products and services are delivered to the customer. In this approach, there is a lack of creative and systematic work activity, with planning and improvements being neglected and defects being identified late in the process, with all the financial implications of this in terms of the working capital employed. Detection will not improve quality but only highlight when it is not present, and sometimes it does not even manage to do this. Problems in the process are not removed but contained, and are likely to come back. It also leads to the belief that non-conformances are due to the product/service not being inspected enough and also that operators, not the system, are the sole cause of the problem. With a detection approach to quality, non-conforming ‘products’ (products are considered in their widest sense) are culled, sorted and graded, and decisions made on concessions, rework, reblending, repair, downgrading, scrap, and disposal. It is not unusual to find products going through this cycle more than once. While a detection-type system may prevent non-conforming product, services and paperwork from being delivered to the customer (internal or external), it does not prevent them being made. Indeed, it is questionable whether such a system does in fact find and remove all non-conforming products and services. Physical and mental fatigue decreases the efficiency of inspection and it is commonly claimed that, at best, 100 per cent inspection is only 80 per cent effective. It is often found that with a detection approach the customer also inspects the incoming product/service; thus the customer becomes a part of the organization's quality control system. In this type of approach a non-conforming product must be made and a service delivered before the process can be adjusted; this is inherently inefficient in that it creates waste in all its various forms: all the action is ‘after the event’ and backward-looking. The emphasis is on ‘today's events’, with little attempt to learn from the lessons of the current problem or crisis. It should not be forgotten that the scrap, rework, retesting, reblending, and so on, are extra efforts, and represent costs over and above what has been budgeted and which ultimately will result in a reduction of bottom-line profit. Figure 1.5, taken from the Ford Motor Company (1985) three-day statistical process control course notes, is a schematic illustration of a detection-type system. Figure 1.5 A detection-based quality system Source: Ford Motor Company (1985) An environment in which the emphasis is on making good non-conformance rather than preventing it from arising in the first place is not ideal for engendering team spirit, co-operation and a good climate for work. The focus tends to be on switching the blame to others, people making themselves ‘fireproof ’, not being prepared to accept responsibility and ownership, and taking disciplinary action against people who make mistakes. In general, this behaviour and attitude emanate from middle management and quickly spread downwards through all levels of the organizational hierarchy. Organizations operating in a detection manner are often preoccupied with the survival of their business and little concerned with making improvements. Finding and solving a problem after a non-conformance has been created is not an effective route towards eliminating the root cause of a problem. A lasting and continuous improvement in quality can only be achieved by directing organizational efforts towards planning and preventing problems from occurring at source. This concept leads to the third stage of quality management development, which is quality assurance:

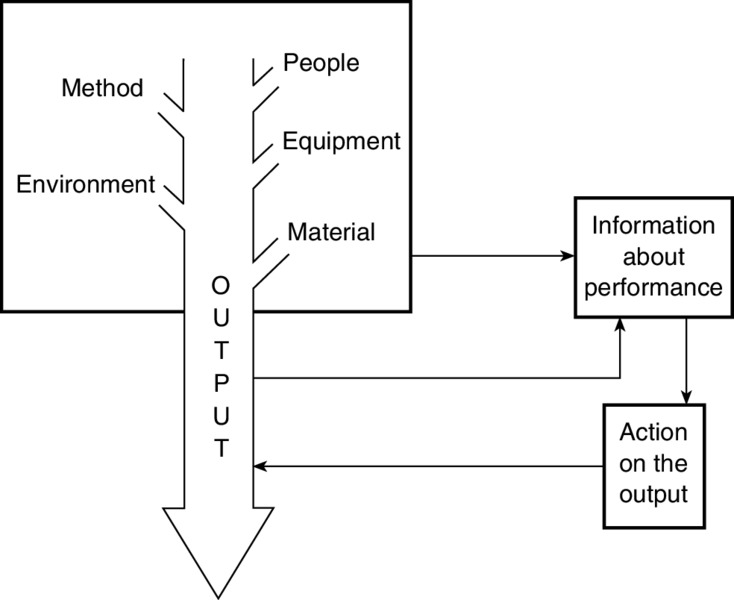

Part of quality management focused on providing confidence that quality requirements will be fulfilled. (ISO 9000 2015) Examples of additional features acquired when progressing from quality control to quality assurance are, for example, a comprehensive quality management system to increase uniformity and conformity, use of the seven quality control tools (histogram, check sheet, Pareto analysis, cause-and-effect diagram, graphs, control chart and scatter diagram), statistical process control, failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA), and the gathering and use of quality costs. Above all one would expect to see a shift in emphasis from mere detection towards prevention of non-conformances. In short, more emphasis is placed on advanced quality planning, training, critical problem-solving tasks, improving the design of the product, process and services, improving control over the process and involving and motivating people. Quality assurance is a prevention-based system which improves product and service quality, and increases productivity by placing the emphasis on product, service and process design. By concentrating on source activities and integrating quality into the planning and design stage, it stops non-conforming product being produced or non-conforming services being delivered in the first place; even when defects occur they are identified early in the process. This is a proactive approach compared with detection, which is reactive. There is a clear change of emphasis from downstream to the upstream processes and from product to process (see Figure 1.6); ‘product out’ to ‘customer in’. This change of emphasis can also be considered in terms of the plan, do, check, act (PDCA) cycle. In the detection approach the ‘act’ part of the cycle is limited, resulting in an incomplete cycle, whereas, with prevention, act is an essential part of individuals and teams striving for continuous improvement as part of their everyday work activities. Figure 1.6 A prevention-based quality system Source: Ford Motor Company (1985) With prevention there is a clearly defined feedback loop with both negative and positive feedback into the process, product, and service development system. Quality is created in the design stage and not at the later control stage; the majority of quality-related problems are caused by poor or unsuitable designs of products and processes. In the prevention approach, there is a recognition of the process as defined by its input of people, machines, materials, method, management and environment. It also brings a clearer and deeper sense of responsibility for quality and eliminates the root cause of waste and non-value-adding activity to those actually producing and delivering the product and/or service. Changing from detection to prevention requires not just the use of a set of tools and techniques, but the development of a new operating philosophy and approach that requires a change in management style and way of thinking. It requires the various departments and functions to work and act together in cross-functional teams to discover the root cause of problems and pursue their elimination. Quality planning and continuous improvement truly begin when top management includes prevention as opposed to detection in its organizational policy and objectives and starts to integrate the improvement efforts of various departments. This leads to the next level, that of total quality management. The fourth level – TQM – involves the application of quality management principles to all aspects of the organization, including customers and suppliers, and their integration with the key business processes. It is a company-wide approach to quality, with improvements undertaken on a continuous basis by everyone in the organization. Individual systems, procedures and requirements may be no higher than for a quality assurance level of quality management, but they will pervade every person, activity and function of the organization. It will, however, require a broadening of outlook and skills and an increase in creative activities from those required at the quality assurance level. The spread of the TQM philosophy would also be expected to be accompanied by greater sophistication in the application of tools and techniques, increased emphasis on people (the so-called soft aspects of TQM), process management, improved training and personal development and greater efforts to eliminate wastage and non-value-adding activities. The process will extend beyond the organization to include partnerships with suppliers and customers and all stakeholders of the business. Activities will be reoriented to focus on the customer, internal and external, with the aim to build partnerships and go beyond satisfying the customer to deligh-ting them. The need to self-assess progress towards business excellence is also a key issue. There are many interpretations and definitions of TQM. Put simply, TQM is the mutual co-operation of everyone in an organization and associated business processes to produce value-for-money products and services, which meet and hopefully exceed the needs and expectations of customers. TQM is both a philosophy and a set of guiding principles for managing an organization to the benefit of all stakeholders. The seven quality management principles are defined in ISO 9001 (2015) as:

Despite the divergence of views on what constitutes TQM, there are a number of key elements in the various definitions which are now summarized. Other chapters will provide more detail of these elements. Without the total demonstrated commitment of the chief executive officer and his or her immediate executives and other senior managers, nothing much will happen and anything that does will not be permanent. They have to take charge personally, lead the process, provide direction, and exercise forceful leadership, including dealing with those employees who block improvement and impetus. However, while some specific actions are required to give TQM and strategic process improvement a focus, as quickly as possible it must be seen as the style of management and the natural way of operating a business. Planning and organization feature in a number of facets of the improvement process, including:

To support and develop a process of continuous improvement, an organization will need to use a selection of tools and techniques within a problem-solving approach (Papalexi et al. 2015). These should be used to facilitate improvement and be integrated into the routine operation of the business. The organization should develop a route map for the tools and techniques that it intends to apply. The use of tools and techniques as the means will help to get the process of improvement started: employees using them feel involved and that they are making a contribution, quality awareness is enhanced, behaviour and attitude change starts to happen, and projects are brought to a satisfactory conclusion. Employees, from the top to the bottom of an organization, should be provided with the right level and standard of education and training to ensure that their general awareness and understanding of quality management concepts, skills, competencies and attitudes are appropriate and suited to the continuous improvement philosophy; it also provides a common language throughout the business. A formal programme of education and training needs to be planned and provided on a timely and regular basis to enable people to cope with increasingly complex problems. It should suit the operational conditions of the business: is training done in a cascade mode (everyone is given the same basic training within a set time frame) or is an infusion mode (training provided as a gradual progression to functions and departments on a need-to-know basis) more suitable? This programme should be viewed as an investment in developing the ability and knowledge of people and helping them realize their potential. The training programme must also focus on helping managers think through what improvements are achievable in their areas of responsibility. It has to be recognized that not all employees will have received and acquired adequate levels of education. The structure of the training programme may incorporate some updating of basic educational skills in numeracy and literacy, but it must promote continuing education and self-development. In this way, the latent potential of many employees will be released and the best use of every person's ability achieved. There must be a commitment and structure to the development of employees, with recognition that they are an asset which appreciates over time. All available means, from suggestion schemes to various forms of teamwork, must be considered for achieving broad employee interest, participation and contribution in the improvement process; management must be prepared to share information and some of their powers and responsibilities, and to loosen the reins. Part of the approach to TQM and strategic process improvement is to ensure that everyone has a clear understanding of what is required of them, how their processes relate to the business as a whole and how their internal customers are dependent upon them. The more people who understand the business and what is going on around them, the greater the role they can play in the improvement process. People have got to be encouraged to control, manage and improve the processes which are within their sphere of responsibility. Teamwork needs to be practised in a number of forms. Consideration needs to be given to the operating characteristics of the teams employed, how they fit into the organizational structure and the roles of member, team leader, sponsor and facilitator. Teamwork is one of the key features of involvement, and without it difficulty will be found in gaining the commitment and participation of people throughout the organization. It is also a means of maximizing the output and value of individuals. There is also a need to recognize positive performance and achievement and celebrate and reward success. People must see the results of their activities and that the improvements they have made really do count. This needs to be constantly encouraged through active and open communication. If TQM is to be successful it is essential that communication must be effective and widespread. Sometimes managers are good talkers but poor communicators. Measurement, from a baseline, needs to be made continually against a series of key results indicators – internal and external – in order to provide encouragement that things are getting better (i.e. fact rather than opinion). External indicators are the most important as they relate to customer perceptions of product and/or service improvement. The indicators should be developed from existing business measures, external, competitive and functional generic and internal benchmarking, as well as customer surveys and other means of external input. This enables progress and feedback to be clearly assessed against a roadmap or checkpoints. From these measurements, action plans must be developed to meet objectives and bridge gaps. It is necessary to create an organizational culture that is conducive to continuous improvement and in which everyone can participate. Quality assurance also needs to be integrated into all of an organization's processes and functions. This requires changing people's behaviour, attitudes and working practices in a number of ways. For example:

Changing people's behaviour and attitudes is one of the most difficult tasks facing management, requiring considerable powers and skills of motivation and persuasion; considerable thought needs to be given to facilitating and managing culture change. The following section analyses the role of senior managers during the implementation of TQM and strategic process improvement. Developing and deploying organizational vision, mission, philosophy, values, strategies, objectives and plans, and communicating the reasons behind them together with the underlying logic is the province of senior management. This is why senior management have to become personally involved in the introduction and development of TQM and strategic process improvement, and demonstrate visible commitment to and confidence in it by leading this way of thinking and managing the business. Senior management must devote time to learning about the subject, including attending suitable training courses and conferences. If this is achieved it avoids false starts and helps to ensure longevity. The decision to start working on TQM and strategic process improvement can only be taken by the chief executive officer (CEO) in conjunction with the senior management team. They have to encourage a total corporate commitment to continually improve every aspect of the business. Quality is an integral part of the management of an organization and its business processes and is too important an issue to delegate to technical and quality specialists. The ultimate aim is to have people taking ownership of the quality assurance of their processes and to have a mindset of continuous improvement. This state of affairs is not a natural phenomenon and does not happen overnight, and senior managers must be prepared to spend time coaching people along this path and providing the necessary influences. Senior managers should be sensitive to the fact that some employees will resist the change to TQM. The usual reasons for this are that they are uncertain of the nature and impact of TQM and strategic process improvement, and their ability to cope: the change may lessen their authority over decisions and allocation of resources, and it threatens their prestige and reputation. If senior managers are personally involved in the change process it can help to breakdown these barriers. Mohammad Mosadeghrad (2014) reported on his research that supportive leadership, consistent support of top management and employee involvement are critical to TQM success. One of the key roles of senior management is to develop effective strategies in order to support and enhance the chances of achieving business excellence (Sallis 2014). The CEO must have faith in the long-term plans for TQM and strategic process improvement, and not expect immediate financial benefits. However, there will be achievable benefits in the short term, providing that the introduction of TQM is soundly based. Senior managers need to create and promote an environment in which, for example:

However, change is not something that any department or individual takes to easily, and administering changes in organizational practices has to be considered with care. It is only senior managers who can influence the indifference and persuade people that the organization is serious about TQM. It is they who have got to communicate in person to their people why the organization needs continuous improvement and demonstrate that they really care about quality. This can be done by getting involved in activities such as:

The improvement process is a series of troughs and peaks (see Figure 1.7). At certain points in the process, the situation will arise that while a considerable amount of organizational resources are being devoted to improvement activities, little progress appears to be being made. In the first three or so years of launching a process of continuous improvement, and when the process is at one of these low points, it is not uncommon for some middle and first-line managers and functional specialists to claim that TQM is not working and start to raise issues such as: ‘Why are we doing this?’; ‘Are we seeing real improvements?’; ‘What are the benefits?’; ‘Have we the time to spend on this?’. If the CEO is personally involved in TQM and perceived to be so, people are much less likely to express this type of view. The CEO and senior managers have a key role to play in helping to get people through this crisis of confidence in TQM. There are a number of mechanisms which can assist with this. For example, the managing director of a specialty chemicals company introduced the concept of ‘Quality Action Days’ to give all employees the opportunity to meet him and express their views and concerns on the company's progress with TQM and what could be done to speed up the process of employee involvement. Figure 1.7 The quality improvement process Organizations are not usually experienced in maintaining the gains made in TQM. In addition to leadership and organizational changes, factors such as takeovers, human resources and industrial relations problems, short-time working, redundancies, cost-cutting, streamlining, no salary increases, growth of the business, and pursuit of policies which conflict with TQM in terms of resources, etc. can all have an adverse effect on the gains made and damage the perception of TQM and strategic process improvement. People will be looking to senior managers to provide continuity and leadership in such circumstances. The first thing senior managers must realize from the outset is that TQM is a long-term and not a short-term intervention and that it is an arduous process. They must also realize that TQM is not the responsibility of the quality function. There are no:

The planning horizon to put the basic TQM principles into place is between eight and ten years. The Japanese manufacturing companies typically work on 16 years made up of four-year cycles – introduction, promotion into non-manufacturing areas, development/expansion, and fostering advancement and maintenance. Consequently, senior managers have got to practice and communicate the message of patience, tolerance and tenacity. It is highly likely that there will be some middle-management resistance to TQM, in particular from those managers with long service, who are concerned with the new style of managing, more than from staff and operatives. In spite of the claims made by some writers, consultants and ‘experts’, senior managers must recognize there is no single or best way of introducing and developing TQM. Senior managers need to commit time in order to develop their own personal and group understanding of the subject; cohesion in the senior management team, which comes from understanding, is important in making the changes which are necessary with TQM. They need to read books, attend conferences and courses, visit the best practices in terms of TQM and talk to as many people as possible. The self-assessment criteria of the MBNQA and EFQM performance and excellence models (as outlined in Chapter 12) can assist in developing this overall understanding. This understanding of TQM will also assist the CEO in deciding, together with other senior managers and key staff, how the organization is going to introduce TQM. For example,

To start and then develop a process of continuous improvement, an infrastructure is required to support the associated tasks and departments and people need to be able to devote time to quality planning, and to prevention and improvement activities. Maletič et al. (2012) point out that continuous improvement is directly related to maintenance performance. Senior managers must diagnose the organization's strengths and opportunities for improvement in relation to the management of quality. This typically takes the form of an internal assessment of employees' views and perceptions (internal and group assessments, and questionnaire surveys), a systems audit, a cost of quality analysis, and obtaining the views of customers (including those accounts which have been lost) and suppliers about the organization's performance in terms of product, service, people, administration, innovation, strengths and weaknesses, etc. This type of internal and external assessment of perspectives should be carried out on a regular basis to gauge the progress being made towards TQM and help decide the next steps. This section is opened by reviewing the leadership criteria of the EFQM excellence model (EFQM 2012; see Chapter 12). The criteria detail the behaviour of all managers in driving the company towards business excellence. They concern how the executives and all other managers inspire and drive excellence as an organization's fundamental process for continuous improvement. The leadership criteria are divided into the following five parts:

Senior managers need to decide the actions they are going to take to ensure that quality becomes the number one priority for the organization. They need to allocate time and commitment to:

It is the responsibility of senior managers to ensure that everyone in the organization knows why the organization is adopting TQM and that people are aware of its potential in their area, department, function and/or process. Their commitment must filter down through all levels of the organization. It is important that all employees feel they can demonstrate initiative and have the responsibility to put into place changes in their own area of work. A company-wide education and training programme needs to be planned and undertaken to facilitate the right type and degree of change. The aim of this programme should be to promote a common TQM language and awareness and understanding of concepts and principles, ensure that there are no knowledge gaps at any level in the organization, and provide the skills to assist people with improvement activities; this should include team leadership, counselling and coaching skills. A planned programme of training is required in order to provide employees with tools and techniques on a timely basis. The CEO needs to delegate responsibility for continuous improvement to people within the organization. Some organizations appoint a facilitator/ manager/co-ordinator to act as a catalyst or change agent. However, if this is to be effective the CEO must have a good understanding of TQM and the continuous improvement process. An infrastructure to support the improvement activities needs to be developed in terms of:

It is helpful to establish a TQM steering committee or quality council type of activity to oversee and manage the improvement process. The typical role of such a group is to:

From the vision and mission statements a long-term plan needs to be drawn up which sets out the direction of the company in terms of its development and management targets. This plan should be based on the corporate philosophy, sales forecast, current status, and previous achievements against plan and improvement objectives (Oakland 2011). It typically focuses on areas affecting quality, cost, delivery, safety and the environment. From this long-term plan an annual policy should be compiled, and plans, policies, actions, and improvement objectives established for each factory, division, department and section. The process of policy deployment ensures that the quality policies, targets and improvement objectives are aligned with the organization's business goals. The ideal situation in policy deployment is for the senior person at each level of the organizational hierarchy to make a presentation to their staff on the plan, targets and improvements. One of the key aspects of policy deployment is its high visibility, with company and departmental policies, targets, themes and projects being displayed in each section of the organization. There must also be some form of audit at each level to check whether or not targets and improvement objectives are being achieved, and the progress being made with specific improvement projects. This commitment to quality and the targets and improvements made should be communicated to customers and suppliers. Some organizations use seminars to explain these policies and strategies. The respective reporting and control systems must be designed and operated in a manner which will ensure that all managers co-operate in continuous improvement activities. The CEO must ensure that his or her organization really listens to what its customers are saying and is sensitive to what they truly need and to their concerns. This customer information is the starting point of the improvement-planning process. For example, a major blue-chip packaging manufacturer works with its customers to ensure that the packaging it produces is suited to the customers' packaging equipment. Senior managers must ensure that corrective action procedures and defect analysis are pursued vigorously and a closed-loop system operated to prevent repetition of mistakes. Positive quantifiable measures of quality as seen by its customers enable an outward focus to be kept on the market in terms of customer needs and future expectations. These typical performance measures include:

They also need to develop internal performance measures on metrics such as:

It is usually necessary to evaluate the current internal and external performance measures to assess their value to the business. Without a measurement system to monitor the progress, continuous improvement will be more difficult (Kerzner 2013). Senior managers should never overlook the fact that people will want to be informed on how the improvement process is progressing. They need to put into place a two-way process of communication for ongoing feedback and dialogue: this helps to close the loop. Regular feedback needs to be made about any concerns raised by employees; this will help to stimulate further involvement and improve communication. This also enables them to pinpoint any impediments to the process of continuous improvement. Continuous improvement can be facilitated by the rapid diffusion of information to all parts of the organization. A visible management system and a storyboard-style presentation in which a variety of information is collected and displayed is a very useful means of aiding this diffusion. The CEO needs to consider seriously this form of transparent system. This chapter defines quality and highlights its importance. It discusses the cost of lack of quality throughout the production of a product and/or the delivery of a service. It introduces the TQM, analysing the key element: commitment and leadership of the chief executive officer; planning and organization; using tools and techniques; education and training; involvement; teamwork; measurement and feedback. A list of points is offered which organizations should keep in mind when developing TQM and strategic process improvement. It also presents the role which senior managers need to take and the visionary leadership they need to display if TQM and strategic process improvement is to be successful. The chapter has outlined some of the things they need to get involved with, including chairing the TQM steering committee, organizing and chairing Defect Review Boards, leading self-assessment of progress against a model for business excellence, developing and then following a personal improvement action plan and sponsoring improvement teams. The chapter has summarized what senior management need to know about TQM and what they need to do to ensure TQM is successful and treated as part of normal business activities.Introduction

What is Quality?

Qualitative

Quantitative

Uniformity of the product or service characteristics around a nominal or target value

![]()

Conformance to agreed and fully understood requirements

Fitness for purpose/use

Satisfying customer expectations and understanding their needs and future requirements

Why is Quality Important?

Quality is not negotiable

Quality is all-pervasive

Quality means improved business performance

The cost of non-quality is high

Customer is king

Quality is a way of life

The Evolution of Quality Management

Inspection

Quality control

What is detection?

Quality assurance

What is prevention?

Total quality management

The Key Elements of TQM

Commitment and leadership of the chief executive officer

Planning and organization

Using tools and techniques

Education and training

Involvement

Teamwork

Measurement and feedback

Ensuring that the culture is conducive to continuous improvement activity

The Need for Senior Managers to Get Involved in TQM

What Senior Managers Need to Know about TQM

What Senior Managers Need to Do about TQM

Summary

References