Chapter 2. Organizational Renewal: Overcoming Mental Blind Spots

Paul J. H. Schoemaker, Ph.D.

Let's make a bet. Write down the ten largest industrial U.S. companies in 1910 (in terms of assets) and see if you can get at least three right. Most people fail this test miserably. (Answers are listed in Table 2.1 in order of total assets.) Companies come and go when viewed in historical terms. Their temporary success, and the arrogance that it breeds, set them up for failure. At first, success actually increases a firm's survival chances, lasting for about 30 to 50 years or so, according to the organization ecologists. Then, the survival curve flattens out, and the tendency to fail in the face of long-term change appears to become the rule rather than the exception.[1]

Table 2.1. Ten Largest U.S. Companies in 1910

- U.S. Steel

- Standard Oil of New Jersey

- American Tobacco

- Mercantile Maine

- Anaconda

- International Harvester

- Pullman & Co.

- Central Leather

- Armour & Co.

- American Sugar

This failure to adapt is still with us today. For example, many leading firms of the disk drive industry surrendered their lead when a new drive (in terms of size and/or technology used) was introduced.[2] Why is it so hard for large, established organizations to adapt to change? External factors play a large part: Legal, fiscal, and national barriers may restrict a firm's growth opportunities; and antitrust laws, state monopolies, price controls, and other forms of regulation constitute barriers to optimal adaptation. However, since organizations have limited influence over these external forces, it is the internal factors that offer the most promising routes to change.

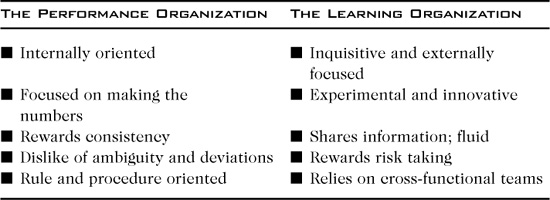

A useful way to understand the barriers to internal change is as a conflict between the learning organization and the performance organization.[3] Firms begin as learning organizations.[4] They are experimental and innovative; employees share information and work together; risk-taking is rewarded. However, once the firm discovers how to earn profits, it transforms into a performance or harvesting culture, striving for reliable performance (see Table 2.2).

Table 2.2. Two Prototypical Cultures

Rules and procedures are developed; employees focus on "making the numbers"; consistency is most rewarded. Those very characteristics that enabled the firm to find a profitable niche in the first place—creativity, flexibility, informality, and experimentation—must largely be suppressed to deliver reliable earnings. In short, the firm's short-term performance may be optimized at the expense of its long-term survival.

Other factors may inhibit the firm's capacity to change as well. For instance, building a large organization with all of its constituencies—shareholders, unions, regulators, licensing partners, other firms, and so forth—requires high organizational legitimacy. Actions must be documented and justified; they must conform to established norms.[5] In addition, decision processes become more complex as the organization grows, straining the abilities of employees to make strategic choices in a timely manner. This organizational sclerosis is compounded, at the individual level, by a human bias toward maintaining the status quo.

For these reasons and more, companies become inert, unable to respond quickly and change sufficiently. To counter these factors, firms must take specific, proactive steps to reinvigorate themselves. It is not enough to know that inertia is a problem—managers must recognize the specific barriers that inhibit change and then develop plans to work around them.

One important leverage point for change lies in the company's decision-making process. The procedures used to identify and evaluate alternatives can be fraught with mental blind spots that lead to distorted estimates and judgments, which keep a company from moving in profitable new directions. In this chapter, we discuss mental blind spots and offer guidelines for overcoming common biases and errors in decision making.

Mental Blind Spots

At every step of the decision process, our minds filter out relevant information, rely on flawed rules of thumb, and direct us toward the known and away from the unknown. The challenge is that these human psychological biases are not always visible and not so easily corrected. They are like illusions or blind spots that persist even after explicit warning or instruction. One of the most powerful of these psychological biases is the very human tendency to prefer the status quo.

Maintaining the Status Quo

Imagine a training program for new managers. At the end of the training, half the managers receive company mugs at random and the other half receive company hats of comparable value. The trainer asks if anyone would like to trade for the other gift. Most of the managers choose to keep the gift they received by chance. Is this rational? A priori, there is a 50 percent chance that each person will get the item he or she wants. Therefore, economists expect that half the participants will trade for the other item. Yet, in experiments like this, the majority of participants choose to keep the original gift, preferring the status quo not change.[6]

The status-quo bias affects all types of decisions. For instance, a manager may subconsciously reject a strategy change because he or she is afraid of the mental turmoil it might engender. A manager who has invested significant time in a project may be loath to drop it before it is finished. In yet another case, a team of employees may fail to consider alternatives, believing that the current situation must be superior or it wouldn't be the status quo.

Researchers have identified a series of factors that underlie the status-quo bias. Building on their work, we advance the following list of factors as especially plaguing innovative decision making in established firms.[7]

- Implied Superiority: The status quo must be superior simply because it is the status quo. Presumably, things are done the present way for some good reason, even if we don't know what that reason is. The aphorism "if it ain't broke, don't fix it" captures this logic.

- Transition Costs: Change can be costly in terms of observable costs, such as time and inconvenience, and in terms of nonobservable, emotional costs, such as fear and mental unrest. Rational transition costs can be a legitimate reason for preferring the status quo, but often they become a rationalization for the irrational factors that tie us to the present.

- Sunk Costs/Benefits: If we've made significant investments in the status quo, it may be difficult or painful to abandon it. Sunk costs are irrecoverable and rationally should not be included in the equation, but they create mental ties that are difficult to break. Likewise, there may be sunk benefits—such as reputation or past glory—that should be irrelevant to the decision to change.

- Omission Bias: We are more likely to be comfortable with inaction (omission) than action (commission). This may be rational from the individual's viewpoint, since most companies require a rationale for action and often accept inaction without further justification. In general, the more alternatives there are and the less we consider them to be viable options, the less regret we feel about not taking action.

Additional factors, of course, can affect the strength of these biases. For instance, greater complexity of the decision and increased importance to the decision maker may exacerbate the status quo bias. However, there are also some factors that may lessen its force and indeed reverse it. Sometimes we overvalue the things that we don't have, because the other side seems "greener." An alternative that has elements of competition or social comparison associated with it, such as someone else's car or job, often seems more desirable than the status quo. Ironically, once we obtain the snappy car or that super job, it may seem less valuable to us. However, the psychological factors tilt toward the side of inertia. They create an atmosphere in which it is difficult for people and their organizations to envision and implement change.

The Decision-Making Environment

Even before a firm begins to make decisions about a specific investment and new directions, its culture and environment may inhibit or promote good decision making. Some organizations, for example, are more attuned than others to the promise of emerging technologies.[8] They are sensitive to the weak external signals that foreshadow shifts in competition or consumer preferences. They possess mechanisms (such as scenario planning) that amplify key information and interpret lessons from other companies and industries about when and how to innovate. In other firms, especially those that have been successful and are well established, new ideas are shunned or viewed askance as disturbing the existing order.

When a company spends time addressing the larger issues that govern decisions, it is involved in the meta-phase of decision making.[9] The meta-phase transcends the cognitive biases of individuals; it also entails questions of organizational design, responsibility, interdepartmental cooperation, trust, and openness to new ideas. Essentially, the meta-phase is a periodic assessment of the optimal balance between the learning organization and the performing organization, which are typically in deep conflict.

Four Phases of Decision Process

For specific decisions, organizations typically go through four phases: decision framing, intelligence gathering, coming to conclusions, and learning from experience.[10]

Decision Framing

Decision frames are the mental boxes we put around information that we perceive as relevant or irrelevant to a decision. As we start the decision-making process, we make assumptions about the timeframe, scope, reference points (such as required rates of returns, performance benchmarks, and relevant competitors), and yardsticks (such as return on investment, market share, and measures of product quality). If these assumptions go unquestioned, we are likely to make poor or inconsistent decisions.[11]

For example, many firms use their past performance, or that of close competitors, as the reference point for judging success. Such myopic framing plagued the automobile industry in Detroit throughout the 1970s and Sears in the 1980s. More subtly, a firm may look at several investment options and use the status quo as its reference point rather than view it as an additional option that must also stand up to scrutiny. This static view ignores the actions of competitors. At Ford Motor Company, the status-quo option now requires the same scrutiny and justification as other options. It directly competes with them in terms of return on investment.

Common accounting procedures tend to amplify certain framing traps.[12] For example, sunk costs are irrelevant to future investment decisions, as noted above. Costs that are irrecoverable should not rationally influence decisions. But when we include sunk costs on the balance sheet as assets, at historical cost, and as write-offs on the income statement, we reinforce our tendency to factor them into decisions. Likewise, the absence of opportunity costs on the income statement and balance sheet reinforces our tendency to underweigh them.

The essence of the framing phase, however, is to think outside the box. Consider one notable example from the world of insurance. In 1986, insurance companies faced a serious liability crisis and decided to add an "absolute pollution exclusion" to their general commercial liability coverage. This left many firms without any coverage for asbestos removal activities, underground storage tanks, hidden chemical problems, and so on. One small company, however, decided to enter the very market from which everyone was retreating, because it felt that the issues were being framed erroneously. The asbestos nightmare had made insurers blind to the fact that some environmental risks were highly manageable whereas others would not be, even within a given class of hazards such as asbestos.

ERIC (Environmental Risk Insurance Corporation), a private company, had gotten its start in the asbestos abatement and removal business. When, in 1986, its business came to an abrupt halt because no asbestos liability protection was available anymore, it decided to enter the insurance field. ERIC believed that one could safely insure a building or warehouse if (1) an in-depth site analysis identified all major asbestos problems, (2) an insurance policy was tailored to the specific circumstance faced, and (3) subcontractors were trained and hired to perform any removal or abatement according to exacting standards. By combining engineering and actuarial analyses, plus having oversight control of subcontractors, an environmental insurance product was launched in segments that traditional insurers shunned. Re-insurers (such as Swiss Re.) bought the concept, and ERIC has since sold millions of dollars of coverage.

Intelligence Gathering

During the information-gathering phase, managers tend to succumb to three main biases: (1) overconfidence, (2) reliance on flawed estimation rules, and (3) a preference for confirming over disconfirming evidence. Overconfidence is a symptom of not knowing what we don't know. Managers from a range of businesses have been asked questions about their industries and found to be almost uniformly overconfident. For example, 1,290 computer industry managers were asked a series of questions about their industry. They were confident that they had correctly estimated ranges for 95 percent of the questions, but in fact were correct only about 20 percent of the time.[13] Overconfidence is especially likely to plague new technology decisions for which little data exists and in which judgment plays a necessary role. The key is to know when to distrust one's intuitions and how to bring implicit assumptions to the surface.[14]

Estimation rules, short cuts that simplify complex judgments, are unavoidable in most cases. For instance, future market share or interest rates may be predicted from current values. However, these estimates often drag down the judgment and result in underestimation.[15] During periods of extreme environmental change, these rules of thumb become quickly outdated and dangerous. Yet, they may stay around long beyond their usefulness. Kantrow[16] recounts a telling example from the infantry. When a cannon was fired, two soldiers would stand at attention, one on the left and the other on the right, with one arm held up to chest height. No one knew the origin or purpose of this ritual. Upon investigation, they found that it traced back to the time that canons were pulled on wagons by horses. The skittish horses need to be held firm when firing the loud canon. Although the horses vanished, the ritual remained. We wonder how many phantom horses still roam the corridors of large established organizations.

Out-of-date rules may persist because of the third bias, a failure to search for disconfirming evidence. Managers seldom approach tasks by looking for evidence that will disprove received wisdom, and organizational filtering reinforces this habit. Often a new generation of managers or start-up companies is needed to make change happen and prove that the impossible is achievable after all. Again, the performance organization, which needs to shield its core activities from disruption, is in conflict with the learning organization, which seeks to question, doubt, and experiment. As George Santyana observed, we only want to believe what we see, "but we are much better at believing than at seeing."

Coming to Conclusions

Numerous informal choices are made along the convoluted path of project idea to formal evaluation, both individually and in groups. The bias against innovation is one factor that influences these choices. In rational models of choice, the ambiguity or uncertainty surrounding a probability estimate should not matter per se. However, people prefer a known probability to an unknown one, even if the plans have the same prospects for success.[17] Thus, projects entailing high ambiguity, such as technological or market uncertainties, are likely to be undervalued as people informally screen projects. In addition, most large firms insist on formal, numerical project justification. The risks of high-ambiguity investments are hard to estimate objectively, which means they may not be seriously considered at all.

Biases creep into other aspects of the choice phase as well. "Groupthink" and other team dysfunctions are well-documented problems of team decisions.[18] These issues must be addressed as organizations and their challenges grow more complex. For instance, in one organization, decision making had degenerated into a guessing game as to what senior management wanted. People abandoned their better judgment in favor of what was politically "correct" or expedient. To counter this, senior managers must encourage diversity of views and the public challenging of accepted wisdom. To be credible, they must reward those who speak out.

One can argue that the choice phase is least marred by biases and errors. Financial analysis imposes strong discipline in the form of net present value (NPV) calculations that would otherwise overwhelm human intuition. Nonetheless, NPV analysis requires unbiased inputs, and finance theory offers little guidance on estimating cash flows and valuing downstream options.

Learning from Experience

Learning from past decisions is an important part of the process, but formidable obstacles get in the way. Ego defenses, such as our tendency to rationalize bad outcomes, make feedback incomplete and inaccurate. Since organizations may make only a small number of truly strategic decisions within any management generation, infrequent feedback is a factor as well. This suggests that process feedback may be more practical than outcome feedback; that is, we need to reexamine how the decision was made, not just whether the outcome was good or bad.

Learning by doing is another kind of organizational adaptation, but it may require a separate organizational unit. IBM adopted this path when developing its personal computer, as did General Motors for its Saturn project. The conflict between the learning and performance organizations is at work here. To optimize efficient performance over the next few periods, the firm should focus on what it knows best; however, to maximize its long-term survival chances, the firm must extend its capabilities through experimentation. The main part of the organization can focus on short-term performance, and a separate unit can look toward the long term. Ideally, however, the two cultures interact. Otherwise, the risk is run that the learning organization fails to leverage the competencies resident in the performing organization. Is it not ironic that IBM produced a highly clone-able personal computer, while being world-class in semiconductor research and development?

Overcoming Mental Blind Spots

There are a few simple techniques to correct for mental blind spots. In addition to creating general awareness, managers should vigilantly try to do the following.

- Surface the implicit assumptions underlying an investment proposal.

- Require the same burden of proof for maintaining the status quo as for other options, while emphasizing that the status quo may erode.

- Look at each investment through the eyes of customers and competitors.

- Realize that estimates may be overconfident or anchored on readily available numbers. Ask "What don't we know?"

- Look at confirming, but especially at disconfirming, evidence.

- Don't shoot from the hip: make an explicit tradeoff of pros and cons.

- Test key assumptions by running a few experiments that challenge them.

- Accept some degree of failure as a necessary price for learning.

Above all, however, senior executives must preach that cannibalism is a virtue in business. Practice it as religiously as Tandem does, with the courage to slash prices on new improved models even though the old product could still be milked at the higher price. Encourage this seemingly destructive, yet fundamentally renewing, frame of mind. The motto is "Eat your young before others do."

Conclusion

Continual self-renewal requires a careful balancing act between the harvesting mode of the performance organization and the quest for experimentation in the learning organization.[19] Each company has to strike its own balance, depending on the competitive circumstances it faces and the stage of its industry's evolution. However, as external change increases, the learning organization clearly deserves more attention.

Too often, when confronted with stiff competition or changing markets, companies just reduce cost. This can take the form of layoffs, outsourcing, downsizing, rationalizing, and so on. Consider the reactions of AT&T, General Motors, Sears, or IBM when confronted with upheaval—they laid off thousands of people. Although useful to a point, these measures at best stop the bleeding. You cannot shrink yourself to greatness. Companies must treat the symptoms as well the deeper causes. Bolder companies, while under attack, will actually try to improve their operations. Not only do they seek greater efficiency, but also greater speed and better service through process reengineering. But even that may not be enough. In many cases, doing the same things cheaper or faster will not cut it. The organization may have to fundamentally rethink its business model and organizational form. This is the hardest task of all, since it requires a change in the mental model and culture that made the firm successful in the first place.

In sum, successful reinvention is the exception rather than the rule. IBM was successful in its reinvention, thanks to bold new leadership and a willingness to embark on a profound transformation lasting well over a decade. Most companies, however, are overly specialized to the particular environment they happen to operate in—especially if they are successful—and then start to lose the ability to change. This limited ability to adapt to external change remains one of the most important unresolved puzzles in business management. Many factors are at play, including the blind spots and complacency caused by mental models that were correct in years past. Awareness of these insidious biases is the first step in mounting a good defense.