Chapter 11. Experience Is Still the Best Teacher

Michael M. Lombardo and Robert W. Eichinger

Much is written about the increasing pace of change, the new challenges leaders face, and what old and new skills it takes to cope. Less is said about how managers and executives develop the skills they need for any future—past or future. In this chapter, we deal with the challenges that create the need to grow—what they are and why they work.

We'll do this by asking you to consult an expert on development—yourself.

The Nature of the Experience

Think back through your life, focusing on work and school experiences. Pick four experiences that may have lasted a few minutes or a few years that have had a lasting impact on you.

Regardless of their length, they share a common truth: They have made a lasting impact on you as a person, how you respond to the world, the skills you now use, and how you approach work. You learned more from these experiences than any others.

- _______________________________________________

_______________________________________________ - _______________________________________________

_______________________________________________ - _______________________________________________

_______________________________________________ - _______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

The Experience Catalog

There continues to be one major finding from all of the research on how people develop the skills they use to be effective: People learn most of the skills they need on the job.

There are four kinds of experiences reported by executives, managers, professionals, teachers, principals, coaches, men, women, and high-school students (everyone who has been studied):

- Key jobs

- Important other people

- Hardships

- Courses (and books, tapes, Internet)

Depending on the study, skill development is reported as 75 percent to 90 percent learned on the job. The events that matter most occur there.

Key Jobs

Most of the hard job skills that matter for performance (e.g., strategy, planning) people learn on the job when they hit fresh challenges. The jobs most likely to teach are starting something from nothing or almost nothing, fixing something broken, switching from line to staff, big changes in complexity or scale, and various kinds of projects (see the exercise in this chapter for more details).

The jobs that are least likely to teach are straight-upward promotions, doing the same type of job again and again, and job switches aimed at exposure rather than at tough challenges.

Important Other People

As with jobs, the people who develop most have the widest variety of other people from whom to observe and learn. Role models play a critical role throughout life, and learning from others is a large category of learning in organizations. Those most remembered are usually bosses and those higher up.

Bosses matter because of what they model: how their values play out in the workplace. The so-called soft skills come into focus here—how people walk their talk, deal with poor performers, make tradeoffs between results and compassion, form networks and alliances, and deal with diversity or solve ethical dilemmas. They also matter because they are a substitute for direct experience—role models can teach through their actions. A novice can learn how a superb marketing manager thinks through marketing plans or observe how an experienced negotiator reaches agreements.

Hardships

No one sets out to have a hardship—hardships just happen to people: missed promotions, demotions; getting fired; business blunders; career ruts; intractable, impossible direct reports; and the like. The key is what people learn from the bad bounces of life.

One key difference between the successful and the less so is that successful people are more likely to report blunders they made and had to rally from. They are much more likely to embrace whatever happens to them, whether they created the situation or not. Rather than resorting to blame, successful people are much more likely to see what can be learned from the situation.

Courses

Curiously, at first, we notice that the content of the course comes in second when people talk about the value of coursework (the Harvard Business School had a similar finding). What we came to understand as we looked further was that timing is everything—it is less what the course is about and more—overwhelmingly more—that the person needs the information badly, right then, to perform on the job. A really developmental course looked more like the other job events above than one would think—it was the first time, different, and difficult. The number one benefit gleaned from courses is self-confidence—belief that a person can grow, change, and improve upon demand.

Now back to you. You probably thought of the four categories of experiences above. You remembered starting a new business or activity or an international assignment or a remarkable boss (2 to 1 odds that you remember the boss fondly), or you recalled something that hit you like a truck—a missed promotion, a truly awful job, a blunder, or having to fire someone. Or you remembered a course that opened a door in your mind just when you needed it most. You remembered all these experiences for the same reasons:

You knew very little about it going in. You had little or no experience in the area. Development is the world of the first-time, the tough, and the different. The varied and the adverse create a need to learn, and most learning occurs while we are in difficult transitions.

You felt you had a significant chance of failure. One of the truths of the human psyche is that people try hardest when there is a 50 percent to 67 percent chance of success. More, and it's too easy; less than half, and we start to cut our losses. So, although there were some strengths you had to fall back on, you thought you might fail. You learned because you had to get through the situation. For the job and the boss, your skills weren't quite up to the challenge; for the hardship, you didn't know if or how you could bounce back—the temptation to blame and deny was tremendous; for the course, it was just-in-time training for your job. Something in the course—whether it was personal self-awareness or a job skill—was pivotal to your performance. Having something at stake lubricates the learning.

You had to make a difference. You had to take charge and lead. You didn't have time to check off with everyone or collect all of the data you needed to feel comfortable.

You felt a tremendous amount of pressure. You experienced deadlines, people looking over your shoulder, travel, or an overwhelming workload. When the stakes are highest is when we are also most motivated to learn.

There are many other challenges that create learning, but these are the most common denominators people recall from any key event or experience. Development is a demand-pull—the experience demands that we learn to do something new or different, or we fear we will fail.

Development is full of paradoxical conditions: adverse, difficult, first-time, varied, full of new people, bosses, good and poor legacies, strong emotions, lack of significant skills, closely watched and yet lonely. It is usually not that pleasant at the time, but it is exciting—much more so than straight-line promotions or succeeding at jobs we already basically know how to do. Development is discomfort, because comfort is the enemy of growth. Staying in our comfort zone or building our nest encourages repetition. Going against the grain, being forced, or venturing outside the cozy boxes of our lives demands that we learn.

Now think of your current job as it exists for you today. Compared with other jobs you have had, how would you rate each of the following on the five-point scale?

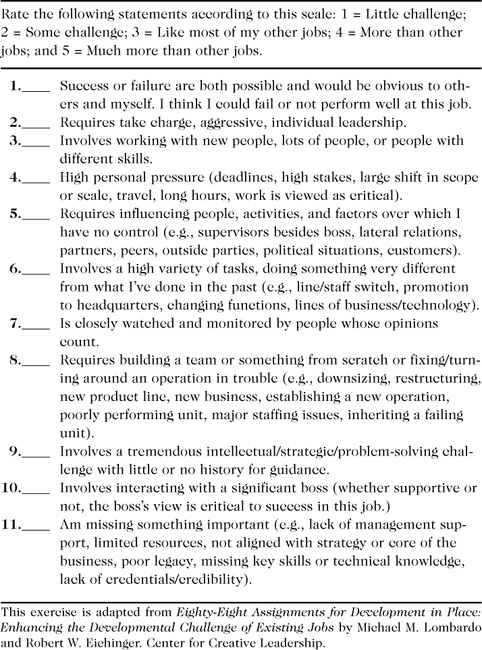

Table. EXERCISE: Developmental Heat

We developed this exercise from the Center for Creative Leadership's studies of developmental assignments. The research team deduced the core elements (reasons why an experience was developmental) of over 2,000 experiences recounted in detail by executives and middle managers. We used this as an exercise in a course for some years. Thousands of people have filled it out and many organizations use it to rate the developmental potential of jobs and other experiences. Following are some interpretive guidelines.

If you scored above 45 (out of 55 possible), this is a very developmental job for you. You are likely in a start-up, a fix-it, or an international assignment. There is very little about this job that you have ever done before. Unfortunately, the job may also be too large a jump for you or anyone else.

If you scored 35 to 45, this is where most developmental jobs fall. Half or more of the challenges are present in a big way.

If you scored 21 to 34, you may have been in this job for three years or more, it may be a straight-line promotion, or you perhaps changed companies (but not basic responsibilities) some time ago. Your performance might not be as good as it once was; you may be getting bored.

If you scored 20 or less, you are comfortable coasting and retired on the job, or you are plotting ways to change your situation or quit. Your résumé may be on the street. You've been in the job too long, it's old hat, it's no longer challenging, and you probably dread going to work in the morning.

True Development

Traditional career paths generally produce narrow and limited specialists. Experience paths that lead to general management and leadership are in reality a zigzag of challenges that have little to do with job titles. They are by their nature predictable only in the sense that we know the enduring challenges or experiences that create the conditions for growth. This year's dead-end assignment may be tomorrow's golden goose if the answers to the questions below are yes.

- Am I missing significant skills?

- Will my performance in this role make an obvious difference in the performance of the unit?

- Do I get the chance to be a big fish in a small pond?

- Will the role expose me to different types of people I have not worked with before?

- Do important people care what happens in this role?

- Is there something particularly adverse or contentious about this role?

- Is there a lot of variety in what I will have to do?

The list could go on, but the core of development is always the same—variety, adversity, jobs, people, courses, and hard times that you're not quite ready for.

For Experience to Matter

People need to master something first. Healthy branches spring from sturdy trunks. Interfering with the process of mastery makes people feel like impostors later. Fast-track, quick promotions continue to derail countless people each year. Real development involves finishing something, having your mistakes come around, and having to fix them.

People need to experience optimum variety of job challenges. Starting things and fixing things and forming strategies at an early point eventually lead to skills growth. Just like for fledgling tennis pros, development is about the small wins that become big wins later.

Development involves heat, emotions, and stakes. We endorse the Mark Twain approach: "People say if a cat wants to sit on a hot stove lid, let her. She'll learn. Now that is true, but she'll never sit on a cold one again either." Development is much more than throwing people into nasty situations and seeing who swims. The goal is to learn to perform, not simply to survive.

What you do has to make an obvious, measurable difference. People don't learn much from situations in which they couldn't influence the outcome. To learn to manage and lead, you have to manage and lead—the success or failure of something has to depend unambiguously on what you do.

That is the how and why of development. We learn most directly from the experiences we have. The more variety and the more transitions we pass through, the more the potential for learning the skills we need later to manage and lead.