Chapter 19. Global Leadership and Global Emotional Intelligence

Stephen H. Rhinesmith

The Need for Global Leadership

As the world economy becomes increasingly global, the demand for leaders who can think and operate on a global basis is sharply rising. The highly touted "War for Talent," documented by McKinsey & Company,[1] is nowhere more evident than in the search conducted each year by global corporations for the talent they need to staff their subsidiaries, manage joint ventures, build and lead global teams, and develop strategies based on an understanding of the complex dynamics of international operations.

There is evidence of a growing global economy everywhere. Swiss chemical manufacturers receive 90 percent of their revenues from foreign income; half the profits of Japan's automakers come from U.S. sales; and U.S. pharmaceutical companies receive, on average, 40 percent of their annual revenues from foreign operations.

Not only are foreign sales growing, but other global forces are at work. Cross-border mergers and acquisitions, strategic alliances, and the emergence of global and regional competitors are forcing companies to understand their foreign environments. Today, as never before, companies must respond to the complexity of a global marketplace.

As a result, the demand for global managers who are able to work across multiple boundaries is fast outpacing the supply of managers with global experience. To meet this demand, companies are not only examining possible sources of new global leaders, they are trying to determine what mindsets and skill sets are necessary for success in a complex global marketplace.

The Need for Leaders with Global Mindsets and Skills

Recent research at Columbia University in New York has isolated two important dimensions of what the authors call a "global mindset."[2] In a wide-ranging review of literature about globalization and global management, researchers discovered a clustering of variables that they believe account for much of the success or failure of executives operating in foreign environments.

The first dimension, cognitive complexity, involves the degree to which a global manager has the basic intellectual capacity to deal with the complexities of a global world.[3] This begins with the technical and professional knowledge to lead an organizational unit on a global basis and extends to the ability to manage the paradoxes that are part of operating in a global environment.

Jean-Pierre Jeannet, in Managing with A Global Mindset, describes what distinguishes domestic, multinational, international, regional, and global mindsets.[4] Fundamentally, a global mindset involves making decisions with increasing reference points. Domestic managers tend to make decisions within the context of their own domestic reference points regarding what is right or wrong, good or bad. Global managers, on the other hand, make decisions within multiple references, contrasting and comparing not only different worldviews, but also the interactions between these worldviews and social, political, and economic megatrends.

In my work with global leaders, I have discovered that there is a vast difference between leaders who can solve complex problems and those who can manage unsolvable paradoxes. Competing global and local needs present a classic paradox for global leadership. The constant drive for greater efficiency calls for global consolidation. While locally there are needs for local customization of products and the decentralized authority to make fast, speedy decisions, there is no final solution to the global-local dilemma. Global managers must learn to manage such issues on an ongoing basis. They must know how to dissect complex global and local interests; they must manage these in a fair and equal way; and they must exercise patience and understanding.

A second aspect of the Columbia criteria for a global mindset is what the authors call "cosmopolitanism," or the ability to look beyond yourself and beyond your own borders to understand and appreciate the differences that exist in many cultures around the world. Cosmopolitanism has long been associated with cross-cultural understanding. However, although substantial research has been conducted on cultural differences and cultural adjustment, no one has developed a way of integrating the following into one framework:

- Self-awareness;

- Knowledge of others; and

- The capacity to work in and adjust to foreign cultures. Global emotional intelligence bridges this gap and fulfills this need.

For the last decade, I have been coaching and training executives on how to develop global mindsets. I also teach the same subject in Columbia Business School's Senior Executive Program. In my work, I have translated cognitive complexity and cosmopolitanism into what I call global intellectual intelligence and global emotional intelligence, borrowing from the recent work of Daniel Goleman and integrating it with my own experiences as a global manager. As can be seen in Figure 19.1, there are two basic components of a global mindset: global intellectual intelligence and global emotional intelligence. I have found that what distinguishes effective global leaders is their intellectual ability to operate globally. I have divided this global intellectual intelligence into two components: (1) business acumen, the knowledge of industry, business, profession, products, and services; and (2) paradox management, the ability to understand and manage the complexities of ongoing dilemmas that cannot be solved in a globally complex world.

Figure 19.1. Basic components of a global mindset.

I have developed the concept of global emotional intelligence as a way of describing the ability to work in and adjust to a changing world. Global emotional intelligence entails both self-management, the ability to work constructively with others, and cultural acumen, the ability to work across cultures. At our consulting firm, we work to develop leaders for a changing world and have developed programs that focus on the components of an effective global mindset. Through our coaching and action learning programs, we work on developing the intellectual and emotional capacities that managers need to execute winning strategies in the global marketplace.

Global Emotional Intelligence

In his groundbreaking book, Emotional Intelligence, Daniel Goleman examines why some leaders with high IQs fail in their responsibilities.[5] Interviewing hundreds of leaders over a 5-year period, he discovered that the key to executive leadership is more emotional than intellectual. In other words, he found that the higher someone is on the ladder of corporate responsibility, the more important it is to be able to work with and through people.

This is not to say that basic IQ is unnecessary, but the defining factor that distinguishes those leaders who are effective at the top of organizations and those who don't make it is most often related to their emotional rather than their intellectual intelligence.

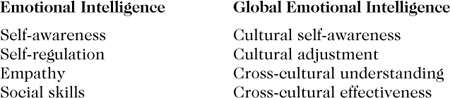

This emotional intelligence, as defined by Goleman, is the ability of leaders to understand and regulate their emotions. There are four components to it: (1) self-awareness, (2) self-regulation, (3) empathy, and (4) social skills. In developing the concept of global emotional intelligence, I have extended each component to a global level in the following manner:

I have also examined the impact of these global components on cross-cultural leadership to see how each becomes a building block for global executive success. I will more fully explore the implications of each factor in the rest of this chapter.

Cultural Self-Awareness

Emotional intelligence begins with self-awareness. People with high self-awareness are aware of their strengths and weaknesses and have realistic assessments of the circumstances in which these strengths and weaknesses will either help or hinder them in their careers. It is important for leaders to understand and accept their strengths and weaknesses, because this is what enables them to ask others for help when they need it. This self-awareness also enables them to make contributions based on their unique skills and abilities.

Cultural self-awareness is the awareness of what it is to be from the country you are from. This includes an understanding of the characteristics, values, and behaviors peculiar to your country, and especially those that may prove helpful or pose problems in working with people from other countries. Cultural self-awareness includes an understanding of your values and prejudices. These values and prejudices are not necessarily right or wrong, but they can create difficulties when you operate in radically different cultures.

Cultural self-awareness is hard to develop without spending time outside your native country. Many companies have learned that leaders sent on overseas assignments better understand the merits and difficulties of transferring knowledge and skills across borders, cultures, and values. They can also better understand different worldviews and appreciate the impact these have on marketing, advertising, human resource management, product development, strategic planning, and leadership activities critical for success in a global world.

Cultural Adjustment

As important as it is, cultural self-awareness is only the first element of global emotional intelligence. Global leaders must be aware of their strengths and weaknesses and be able to "self-regulate" their emotions so that their feelings do not negatively affect those with whom they work. An often-cited example of the lack of self-regulation is the executive who is "moody," or worse, yells at his or her colleagues when frustrated and upset. This lack of consistency ultimately undermines leadership effectiveness.

In my experience coaching and training executives from around the world, I have found that self-regulation is much more likely to be troublesome than is self-awareness. With 360° feedback training, many executives become aware of their strengths and weaknesses; however, it is one thing to be aware of a weakness and quite another to regulate it.

The extension of self-regulation to a global context involves cross-cultural adjustment. This is the ability to enter a new culture with different values and patterns of behavior and adjust to the "shock" that occurs when you're faced with managing yourself and others in an environment in which expectations may be largely unknown.

Culture shock has been defined in the psychiatric profession as a "transient personality disorder." When I was president of the American Field Service International Student Exchange Program, we sponsored 10,000 high school students a year from 60 countries. The students lived with a family in a foreign country for up to a year. Each year, a very small percentage was unable to adjust to new circumstances. In some cases, students returned home with psychotic disorders. Amazingly, however, after 2 or 3 months at home, they were perfectly normal again. They had realigned themselves to familiar surroundings and were able to regain their normal capacity for living.

When examining the cause of their cultural maladjustment, we discovered that some of the students were unable to adjust to new cultures because they had never experienced failure in their own culture. When entering a new culture, it is inevitable that you will not perform at the level you achieved at home. Many fully functioning, achievement-driven executives in their 30s and 40s find themselves regressing to the behavior of 6- or 7-year-olds when they go abroad. They don't speak the language well, don't know how to act, and don't know how to manage effectively in their new environment.

Having the emotional capacity to self-regulate under these conditions requires you to have a strong self-concept, great personal discipline, and a basic faith in yourself and others that allows you to look at the positive over the negative and adjust quickly to the demands of the new situation. This is, of course, more easily said than done. When you're in a foreign environment, the landscape is filled with the potential for personal, professional, and business blunders. To make matters worse, you don't have the personal and organizational capacity to make the complex tradeoffs that are involved in managing the paradoxes of different value systems. Although rates of success vary, failure rates of 25 percent to 50 percent have been documented for U.S. expatriates on overseas assignments, with cost estimates of $50,000 to $250,000 per failure. This is a powerful incentive for companies to develop executives who can operate on a global basis.

Cross-Cultural Understanding

The third aspect of Goleman's emotional intelligence is empathy. This is the basis for what I call cross-cultural understanding. Without empathy, it is difficult for leaders to place themselves in another person's shoes. If you cannot identify with another's situation, it is difficult to supervise, motivate, or develop people, or to sell, negotiate, and work with customers or clients.

Many executives have told me that they feel guilty for not taking the time to understand the needs of those who report directly to them. When CDR ran a leadership integration program for the merger of Bank of America and NationsBank, we discovered that many executives defined the purpose of the new Bank of America as being able to "help people realize their dreams." While this may sound like hyperbole, there is a great deal of evidence to support the contention that helping people fulfill their dreams is a powerful leadership idea. This, however, requires leaders who are willing to take the time to understand the dreams, hopes, and fears of others. While many executives have come to better understand the needs of their clients and customers, many of them consistently report that they fail to allocate enough time to understand the needs of their colleagues and the people who report directly to them.

There is no question that empathy and cross-cultural understanding constitute critical aspects of global emotional intelligence. Without empathy, it is impossible to truly understand people, to gain their trust, or to provide products and services that are responsive to their needs. Empathy is also required to understand the strategy of competitors, to negotiate with governments, and to have credibility with the people with whom you work on a day-to-day basis.

In recent years, many cultural factors influencing global leadership have been examined. These include an understanding of group-oriented versus individually-oriented cultures; differences in perception of time and space; differences in attitudes toward hierarchy and authority; differences in communications and language; and differences in business and personal relationships. All of these cultural variables affect the way in which people work together across borders and need to be understood by those hoping to lead effectively in a global organization.

One example of a cultural factor that impacts global leadership is the difference between "doing-oriented" versus "relationship-oriented" cultures. Doing-oriented cultures, like the United States, Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom, and Scandinavian countries, tend to sell products and services based on technical and performance criteria. People from relationship-based cultures, like Latin America, the Middle East, and many African countries, tend to sell products and services based on relationships, personal compatibility, and chemistry. When companies from a doing-oriented country try to sell products and services based mainly on technical criteria in a relationship-oriented country, they may encounter difficulty closing business deals, because they have not spent enough time developing a personal relationship with their clients or customers.

Cross-Cultural Effectiveness

Finally, the fourth element in emotional intelligence is what Goleman identified as social skills, or what I call cross-cultural effectiveness. This includes a range of interpersonal skills associated with working with others, such as communications, decision making, motivating, negotiating, and conflict management.

The final challenge of cross-cultural effectiveness (assuming you now have the ability to understand differences between your culture and others) involves achieving business objectives that may conflict with cultural values in other countries. Welcome back to paradox management, the intellectual side of global mindset!

Managing cross-cultural paradoxes in business ethics is one of the most challenging aspects of cross-cultural effectiveness. In this instance, a global manager must (1) analyze and understand cultural differences (cross-cultural understanding); (2) self-regulate against the frustration that comes from not being able to solve conflicts between local values and business ethics (cultural adjustment); (3) maintain a balance between business interests and local needs (cross-cultural effectiveness); and (4) understand his or her strengths and weaknesses in dealing with other cultures (self-awareness).

In her book on this subject, Eileen Morgan advises global managers to create "maps for cross-cultural ethical navigation."[6] She recommends that managers use these paradox grids in all aspects of global intellectual and emotional intelligence to (1) understand cross-cultural challenges from different perspectives (self-management); (2) analyze the force of these perspective (business acumen); (3) manage the contradictions of the conflicting perspectives (paradox management); and (4) learn to work effectively in developing what she calls "communities of practice" to manage these conflicts on an ongoing basis (cultural acumen).

Cross-cultural effectiveness is very simply the ability to put it all together. It is the ability to translate knowledge, mindset, and skills into appropriate leadership behavior and a style that enables you to achieve business objectives in challenging cultural situations.

So, we conclude that global emotional intelligence, with its self-management and cultural acumen, is as important for global leadership as global intellectual intelligence, with its business acumen and paradox management. What does this mean for the development of global leaders?

Developing Global Emotional Intelligence

Almost all companies use international assignments as a method of developing global emotional intelligence. Coca-Cola, Colgate Palmolive, IBM, Philips, Matsushita, Sony, and Nestle have long used foreign subsidiaries as a source of executives to fill corporate management ranks and as a training ground where home country executives learn to operate from a broader perspective.

But now, more and more global executives are needed not just for international assignments, but for global task forces, joint venture teams, globally functional roles in company headquarters, and a variety of other jobs that require a global mindset and skills. Companies like IBM, Philips, and Matsushita have begun to track people on a global basis to develop a worldwide talent pool. NEC has a talent system that evaluates all executives every 3 years specifically on "their ability to adapt to international environments."[2]

GE's Medical Systems Group in Milwaukee derives more than 40 percent of its income outside the United States. To ensure that it had the leadership necessary to manage these wide-ranging operations, GE developed a Global Leadership Program. During this multi-year process, managers from Europe, Asia, and the United States worked together on action-learning projects to solve globally complex business problems. At the same time, as individuals, they learned to more effectively work with their colleagues across cultural and functional differences.

These global action-learning programs are a popular way to develop global intellectual and emotional intelligence. Using 360° feedback as well as extensive executive coaching, they emphasize cultural acumen as well as self-management. Over time, this results in managers who have an intellectual understanding of global management and a better understanding of their emotional and personal capacity to manage in a global marketplace.

Manfred Kets de Vries and Christine Mead point out that there are three fundamental variables that affect the development of global managers.[7] The first, childhood development, affects people's ability to adapt to new situations and the self-confidence they need to handle difficult circumstances. There is little companies can do to affect these capacities. These are characteristics that should be included in executive selection processes.

The second factor is professional development. Here, corporations can use a wide range of management training and coaching experiences to help managers understand and incorporate new mindsets and skills that will increase their global emotional intelligence.

The third factor influencing global leadership success is organizational development, or the degree to which a company is well run as a global organization. I have watched many leaders fail because they were in organizations that did not understand globalization. As a result, they placed people in positions that were untenable, unsupported by the cultural values or the management process and systems needed to operate a global company.

All of this calls for an integrated approach to globalization. In my book, A Manager's Guide to Globalization, I advocate supporting a global strategy and structure with a global corporate culture and managers who have the global mindset and skills needed to manage world-class competitive organizations.[8] By working with many companies on globalization, I have learned that the key to globalization is not where you do business, but how you do business. Globalization is ultimately the business of mindset and behavior change.

I have found global emotional intelligence a useful way to summarize the critical characteristics of effective global leadership. Within the concept of global mindset and skills lies a cluster of four essential components: cultural self-awareness, cultural adjustment, cross-cultural understanding, and cross-cultural effectiveness. As global leaders around the world recognize these components and work to develop them, they will come to understand themselves and others in a way that will contribute to their business success and their greater personal fulfillment in a global world.