Chapter 21. Effective Crisis Management: Now More Than Ever

Idalene Kesner

Ever since the incidents involving Johnson & Johnson and the Tylenol poisonings in 1982, corporate executives have been keenly aware of the need for effective methods to deal with organizational crises. Indeed, following the Tylenol incidents many firms established crisis management programs. Although these programs vary from firm to firm, the overriding message of crisis managers has been that effective crisis management begins with prevention.

Experts agree that the best-handled situations are the crises that never happen—the crises that are averted because of outstanding detection mechanisms both inside and outside affected organizations. And, although crisis prevention remains the mantra of all good crisis managers, managers also know that not every crisis can be prevented. The terrorist actions of September 11, 2001, that destroyed New York City's World Trade Center Towers and damaged the Pentagon in Washington D.C. are tragic reminders of this fact. These events confirm that effective crisis management is also about effective crisis preparation and response.

What has changed in the way we think about crisis management today? What steps can managers take to better prepare themselves and their organizations? These and other questions will be answered as we explore the realities of managing crises in an environment that too often presents situations that are unexpected and unpreventable.

What Is a Crisis?

While not all crises are alike, most have several features in common. Specifically, crises are situations that run the risk of escalating in intensity, interfering with normal business operations, jeopardizing a company's positive public image, damaging a company's bottom line, and falling under close media and/or government scrutiny.[1] Crisis management, therefore, is about employing effective management techniques to minimize the damage and negative impact on a company and to gain control of the situation.

A well-handled crisis is one in which the problem disappears quickly; there is minimal media or governmental attention; the company's sales, profits, and productivity are not severely negatively affected; and the company's reputation and credibility remain unscathed among key constituents. On the other hand, a poorly handled crisis can cause numerous negative outcomes, such as significant damage to the firm's reputation or credibility, and it can result in litigation, fines, or penalties. Some crises can lead to changes in senior-level personnel and/or a loss of employees, employee loyalty, or employee productivity.[2]

Crisis Prevention

Over the years, managers have learned firsthand that crises come in all shapes and sizes, including product failures, plant accidents, industrial relations incidents, cash and financial problems, succession events, and even public perception crises. In most cases, crises begin with one or more warning signals. In fact, the earlier a manager detects these signals, the more likely he or she is to prevent the situation from escalating to the level of a full-blown crisis. The key, therefore, is putting signal-detection mechanisms in place throughout the organization.

Why aren't these mechanisms prevalent in all organizations? One reason is that managers sometimes labor under the misconception that a crisis will never impact their company or industry. This misconception is particularly acute if a company and its industry have been unaffected by prior crises. Of course, in today's environment almost no company can make such a claim. The interconnectedness of organizations and the pervasiveness of media coverage challenge managers in even the most insular organizations from claiming they are invulnerable.

Companies may fail to set up early-warning systems because of cost. Signal-detection mechanisms can be expensive to install and maintain. Yet, if one compares the costs of detection to the costs associated with handling a full-scale crisis, investments are more than justified. However, short-term financial concerns often override long-term investments, especially when the cost savings from averting a crisis cannot be directly identified or easily quantified.

Nevertheless, it is impossible for even the most prepared organization to implement a system that will detect every conceivable crisis. The best response, therefore, is to conduct a crisis vulnerability audit.[3] This audit begins with identifying the full range of crises that may affect an organization. Next, managers in each division, product area, or functional area assess their department's vulnerability to each type of crisis. Figure 21.1 provides a representation of this type of audit. While the actual audit includes far more detail, the end objective is the same. Managers must uncover areas in which their company is most susceptible and invest in early-warning devices in the areas of greatest vulnerability, where the damage caused by potential crises is the greatest.

Figure 21.1. Crisis vulnerability audit.

Overall, when it comes to crisis prevention, experts often refer to the crisis management paradox. Simply put, this rule of thumb suggests that the less vulnerable managers think their firm is, the fewer crises they prepare for and the more vulnerable their firm becomes. Conversely, the more vulnerable managers think their firm is, the more crises they prepare for and the less vulnerable their firm becomes.

Crisis Preparation and Crisis Response

Every organization must weigh the costs of early-warning detection systems against the likelihood that a crisis will occur in a given area and the seriousness of the damage that could result. Yet, there are some situations for which warning signals are undetectable by management, and there are some times when, despite detection, the crisis cannot be averted. Under these circumstances, the best managers can do is have sufficient crisis-management response systems to minimize resulting damage, especially loss of life. The most common crises in this category are natural disasters, such as earthquakes, hurricanes, or tornadoes; yet, following September 11, 2001, we now include on this list acts of domestic and international terrorism.[4]

When this type of crisis hits, how does the role of crisis manager change? Perhaps the most significant change is a shift in focus from crisis prevention to crisis preparation and response. Fundamentally, crisis preparation involves identifying the processes and procedures one will use during the crisis. Disaster-response manuals, for example, can be used to detail immediate actions, including evacuation plans, succession procedures, and even communication steps. These items minimize the need for contemplation and debate in the event of a crisis, thereby shortening decision-making and response times. This in turn can minimize the trauma and potential damage. Of course, signal detection is still important even when crises cannot be prevented. The sooner managers detect crises, the sooner they can launch response plans.

Determining a firm's preparedness requires a different type of audit than the crisis vulnerability audit. A crisis capability audit explores how well a firm is equipped to respond. For this type of audit, each area of the firm must evaluate its ability to detect, to respond, to repair, and to incorporate lessons learned.[5] This type of audit might also involve highlighting specific weaknesses so that they can be targeted for improvement. Figure 21.2 provides a representation of this type of audit.

Figure 21.2. Crisis capability audit.

Another important part of crisis preparedness is the establishment of a crisis management team.[6] This small team helps plan for and manage the crisis. An effective team is one that includes appropriate senior managers, representation from key areas (e.g., legal, financial, human resources), as well as communications experts. Other functional or divisional executives might need to be included depending on the nature of the crisis. Some organizations even go so far as to establish multiple teams, with each team focusing on a unique area of vulnerability. Each team often includes different experts inside the organization as well as external counselors available on demand.[7]

While it is important that crisis management teams have strong representation from key areas of management, the characteristics of its members may be even more important. Because their role involves both preparation and response, team members must be knowledgeable about the company, the industry, and the situation. They must demonstrate good judgment and the ability to maintain perspective even under extreme pressure. They must possess sufficient authority and capability to make decisions quickly. In addition, members must be able to manage time effectively, to delegate, to communicate, and to work well in a team setting.

The role of the crisis management team varies depending on the stage of the crisis.[8] In the pre-crisis period, the team is responsible for

- Intelligence gathering and information monitoring;

- Threat assessment, scenario development, and testing;

- Episode investigation;

- Simulation training; and

- The establishment of communication channels.

During the crisis period the team's responsibility shifts to the following:

- Fact gathering about the actual crisis event;

- Situation evaluation;

- Options assessment;

- Action selection;

- Issuance of instructions;

- Establishment of spokesperson responsibility and maintenance of effective communication channels; and

- Progress monitoring.

Finally, in the post-crisis period the team's role includes the following:

- Scenario reconstruction;

- Improvement of early warning systems, information systems, and communication systems;

- Implementation of damage limitation and long-term recovery mechanisms; and

- Development of a new strategy.

Crisis Communications

While crisis preparation and crisis response have increased in importance as the environment has become more hostile, the greatest change for crisis managers has come in the area of communications. More than ever before, managers rely on their communication strategies to minimize the potential damage to their companies' reputations and turn the negative aspects of bad situations into positives.

The pervasiveness of the media and the constant search for news stories has created explosive coverage of events. Even minor incidents can become crises when under the spotlight of media coverage. Moreover, television and electronic media are used more extensively than in the past, creating coverage that is instantaneous and constant.

Perhaps the most significant change in the area of communications is the increased need for full disclosure. Crisis managers should be wary of advice to keep a low profile or hide information. Similarly, advice that encourages managers to treat reporters as adversaries during times of crisis can prove damaging. While advice such as this might have been appropriate in an environment of limited media coverage, today it is unlikely to protect a firm. Accessibility to information from sources such as the Internet means that the media can and will uncover information about the crisis even without the firm's cooperation. Therefore, it is better to be the source of information, especially if one can influence the tone and substance of the message.

Full disclosure is critical if future injury or fatalities are likely as the crisis unfolds. Moreover, full disclosure can be helpful when the fictions surrounding the crisis are worse than the facts or when the organization shares the role of victim—as is often the case in unpredictable crises. In these instances, it is important to communicate the facts early and to a broad audience.

Crisis communications today means more than just sharing information with people inside the company. It means the firm must take responsibility for delivering its message externally to key constituents and to the public at large. Considering the public's interests requires managers to balance the advice of lawyers with the advice of public relations experts. Now more than ever, crisis managers must understand the role of reporters as well as educate them about their company, its industry, and the facts surrounding the crisis. As such, crisis managers at all levels can benefit from advanced crisis-communications training.

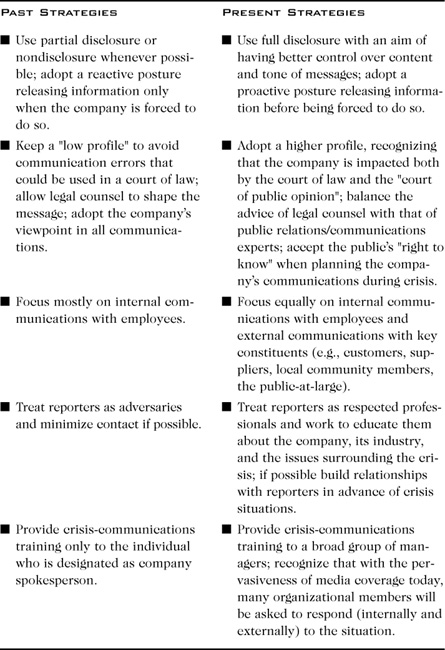

Overall, one must remember that a crisis can destroy a company not simply because of what takes place in a court of law, but also because of the damage to the firm's reputation in the court of public opinion. An effective communications strategy is one of the most important tools a manager can use to mitigate this damage. Table 21.1 lists past and present communication strategies.

Table 21.1. Crisis Communication Strategies

Conclusion

It is no secret that effective crisis management can be a career maker or a career breaker for the managers who must handle these tense and often chaotic situations. The same extremes are also true for organizations. Firms that handle crises well can survive and perhaps even thrive, while those that handle crises poorly may face permanent damage or even bankruptcy. The complexities of today's environment remind us that managers can no longer take for granted the predictability or preventability of crises. They can no longer take for granted that they will know what to do when the unimaginable happens. Handling these situations requires steady nerves, excellent judgment, and strong communications skills. For firms that have not begun developing managers for the uncertainties that lie ahead, it is time to take notice—the wake-up call has been sounded.