Chapter 24. Morphing Marketing: Dissolving Decisions

James M. Hulbert and Pierre Berthon

Marketing in the 21st century is in a process of rapid metamorphosis. We will identify the shift from the material economy to the information economy as the primary driver in the evolution of the key divisions, distinctions, and boundaries that constitute the practice of marketing. We will explore the rise of the information economy and its impact; identify some of the key divisions, distinctions, and boundaries in marketing that are being dissolved, and with each, suggest how the practice of marketing will change; and we will argue that this process of dissolving of old distinctions and the concomitant creating of new ones will lead to an age of unprecedented uncertainty: The rules of the games are being redrawn; marketing is metamorphosing.

From Material to Information

The transition from the material to the information economy entails a change in location of economic value. Simply, economic, psychological, and social value is less and less located on the physical level, and more in the virtual realm of information and ideas. A number of prominent authors anticipated the emergence of this postindustrial economy, the characteristics of which are the rise of service and information as the critical factors of carriers of industrial value.[1] The critical role of knowledge in the late 20th century is cogently illustrated in the words of T. A. Wilson, chairman of Boeing, who stated that Boeing was in the knowledge business—and that it was incidental that airplanes were the end result.[2] This typifies the increasing importance of knowledge, for physical materials, processes, and techniques are no longer a sustainable source of competitive advantage.[3] We show this transition graphically in Figure 24.1 and document the shifting expenditure pattern in Figure 24.2.[4]

Figure 24.1. The transition to the information economy.

Figure 24.2. Changing investments: Ratio of informational to material spending.

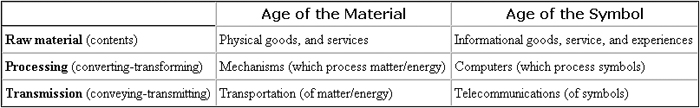

For this transition to occur required a convergence of the process of conversion and the process of conveyance. As Table 24.1 indicates, there is an interesting parallel between the process of industrialization and that of the information revolution. Computers have been around for a long time, but until the advent of the Internet and the World Wide Web, the full impact of increases in information-processing capacity could not be manifest.

Table 24.1. Matter and Symbol

With the transition to the information economy, however, new distinctions become important. Increasingly, the source of competitive advantage will lie in the creation of these new distinctions. For example, B. Arthur has pointed out that economics has traditionally used an assumption of diminishing returns to scale.[5] Yet, many information-based products do not fit these assumptions. Rather, they are subject to flat or increasing returns, sometimes dubbed "network economics," wherein the prize to the winner can be immense (witness Wintel!), but with little or nothing for other competitors. The importance of setting standards (the creation of new distinctions) for many of these new markets is so great that leading competitors in high technology go to enormous lengths to protect their opportunity to become a standard. The premium for being the information standard is likely to continue to increase in the 21st century.

Thus, with the rise of the virtual, traditional physical boundaries, distinctions, and divisions that delineated and constituted the practice of marketing are being dissolved and new ones created. We now consider a few of the more pertinent.

The Dissolution of Divisions

The dissolving boundaries we focus on are within the firm (marketing versus the rest of the firm: marketing dissolves into the firm); among firms (disintermediation, reintermediation, alliances, co-ventures, networks, clusters); between firms and customers (creation and co-creation); among offerings (products, services, and experiences), and among countries (national dissolves into regional and global marketing).

Within the Firm

With the rise of the virtual, the ideas that constitute a practice become more important than the traditional physical demarcations of organizational specialization. Thus, the marketing department becomes the marketing philosophy.

For much of the 20th century, a departmental view of marketing sufficed. As competition intensifies, however, firms will find that they cannot and will not solve their marketing problems by delegation to a traditional marketing department.[6] This recognition is already leading to a growing chorus of voices calling for change in the way that we think about marketing.[7] We have coined the phrase total integrated marketing to describe the required change of outlook. The change will pose many difficulties in implementation—because it constitutes a change in mindset.[8] As McKinsey found working with Kraft General Foods:[9]

The sources of customer value were no longer just marketing-based. The entire organization, from R&D to marketing, to packaging, to manufacturing and distribution, to the field sales representatives working the customers, was essential to identifying and delivering value to consumers.

Thus, a significant change of in the role of marketing is inevitable. Lehmann comments, "Focus on customers is now at least discussed by people in R&D, design, quality departments, operations, and even finance. While this is potentially very good for business, it is not good for the marketing function per se."[10] As a more appropriate and broader view of marketing evolves, the outlook for marketing managers with a more traditional, departmental view of marketing is likely to deteriorate significantly. To get marketing out of the department and into the business will prove a significant challenge both for managers within the marketing function and elsewhere.[11] To work across the boundaries of traditional functions will demand high levels of interpersonal skill as well as a holographic understanding of the business.

Among Firms

Disintermediation (reintermediation), alliances, co-ventures, networks, and clusters are all representative of an evolving vocabulary that reflects changing relationships among firms.

With the rise of information, the boundaries—both spatial and temporal—between firms are dissolving. Ten years ago, the typical large company shunned joint ventures, cooperative agreements, and anything that smacked of less than complete control. Today, large companies are engaged in many such alliances, new words such as co-opetition have been created,[12] and many firms have venture capital operations. One way to view these changes is that they reflect attempts to hedge against increasing uncertainty.[13] However, these new approaches change and complicate the job of managing relationships with suppliers, customers, and competitors in ways quite alien to the more simplistic approaches that characterized much of the 20th century.

Vertical marketers act simultaneously as retailer, wholesaler, and manufacturer, in effect disintermediating products and markets. Dell Computer, Ben and Jerry's, Starbucks, and The Body Shop all made obsolete the traditional distinctions between channel members.

As old distinctions dissolve, however, new ones are created. Thus, with the rise of the virtual and the information economy, new intermediaries (or, as they are sometimes called, infomediaries) with powerful brand names such as Amazon, AOL, and Yahoo! have arisen.

An extension of the between-firms theme is that of between-industries. The Internet has reduced entry barriers in many industries. Deconstruction of value chains, combined with the growth of outsourcing and contract manufacture, create a dramatically more complex milieu than that of the traditional "industry." Further, the Internet means that constructing a low-cost virtual presence is possible for entrepreneurs anywhere in the world, even though lack of brand recognition still presents them with a serious problem. Yet, managing and eliminating customer risk will be important to the success of new Internet-based businesses and may provide opportunities for branded intermediaries. Information-based products and services will almost certainly gain most from the Internet revolution, since physical products, particularly if they require direct experience, will always require some form of conventional distribution system.

Between Firms and Customers

With the switch from physical products and services to informational products and services, the distinction between producers and consumers, firms and customers, is blurring. Both produce and transform information, and this is leading to new forms of relationships and interaction.

Traditionally, there has been a sharp demarcation between a company and its customers. These distinctions are clearly becoming increasingly blurred. As we have documented elsewhere, co-creation with customers is an increasing facet of economic activity.[14] Recognition of this interplay is also implicit in much of the research about first-mover and pioneering effects. Classical marketing treated customer preferences as endogenous, but in newly developing markets it is clear that they should be treated as exogenous.[15] As Peter Drucker pointed out, customers are not found but created, and the logical extension of this concept is the co-creation of value by customers and companies.[16]

In the information economy, the Internet is facilitating this change by transforming the process of marketing communication. Historically, in consumer markets, information has been primarily sent one-way in undifferentiated one-to-many mass communication. Not only does the Internet allow consumers to be addressed relatively cheaply as individuals, they can also easily communicate with their suppliers and with other consumers, both enthusiastic and disaffected. Thus does yet another barrier dissolve.

Further, as a result of intensifying competition, the ability to create and sustain competitive advantage by practicing the tried and true principles of neoclassical marketing will undoubtedly diminish in the future. Of course, we do not argue that one should not listen to customers and attempt to fill their articulated unmet needs and wants. Yet, in a world in which all surviving competitors will subscribe to such a view, the prospect of attaining more than a fleeting advantage from such strategies seems remote indeed. We have elsewhere pointed out the limitations of this essentially responsive or adaptive view of the marketing task.[17] In the 21st century, instead of responding to existing customer wants and needs, successful firms will have to create them; this is not only a distinctly challenging task, but also one alien to traditionally trained marketers. Indeed, as the barrier between the firm and its customers dissolves in this way, traditional marketers are likely to become discomfited if not obsolete.

The shift in emphasis to more basic, even disruptive, kinds of innovation and away from the evolutionary "flanking" efforts, for which marketers have become notorious, toward market development rather than market servicing, will also pose new questions for marketers, many of whom will be ill-equipped to deal with them. Indeed, customers will increasingly be highly informed and in a very different bargaining position. Historically, information acquisition was difficult and expensive; today, the electronic revolution is rapidly transforming the situation. This process has already occurred in financial markets where real-time information is available on virtually a global basis. Similarly, the World Wide Web is providing a low-cost means of accessing information about product and markets. As inefficiency is driven out, the only sustainable price differences will be those reflecting differences in customer perceived value; those due to lack of information will disappear. Not only will information technology lower costs by permitting vicarious search, it will increasingly permit the buyer–seller matching via intelligent search engines. Disintermediation will certainly increase as a result.

Among Offerings

Boundaries that are in the process of dissolving are the distinctions that have traditionally been made among products, services, and experiences—information constitutes yet transcends each.

The product–service–experience distinction is essentially arbitrary inasmuch as offers purchased by the majority of buyers comprise a mixture of tangibles and intangibles. Indeed, structural changes in the economy and company strategies often transform products into services, services into experiences, and so on. For example, an activity conducted inhouse by a manufacturer is typically counted as value-added in the product sector; that same activity (unless manufacturing) conducted by an outsourcing supplier, is counted in the service sector. For example, because McDonald's operates restaurants, the government classifies it as a service business; however, its strategy of growing take-home sales (local manufacturing of sales for later consumption) has been so successful that in the United States, 60 percent of revenues are attributed to product removed from the premises before being eaten. As our children have birthday parties at McDonald's or play in the playgrounds at these sites, they are also involved in co-producing experiences that accompany the products and services.

Durable goods manufacturers also provide interesting illustrations. For example, commercial jet engine manufacturers traditionally made little profit on engine sales; profit was made on spares and maintenance. However, as engine quality and performance has improved, the revenue yield from these activities is declining and manufacturers are actively discussing pricing on a per-hour of operating life basis. Furthermore, products as diverse as automobiles, railroad cars and engines, computers and copiers, light bulbs, and furniture are now offered as "services" to market segments comprising customers who prefer to avoid the initial capital outlay by renting or leasing. The really important distinction is now recognized to be that between the marketing of tangibles and the marketing of intangibles, but as any successful brands manufacturer will tell you, the latter is as central to their success as it is to major services companies.

Among Countries

With the rise of global information networks, the time–space barriers that are so real for physical products and services are rendered irrelevant for informational offerings.[18] Under the influence of GATT and WTO, as well as regional groupings such as NAFTA, the EU, and MERCOSUR, the national boundaries that so clearly demarcated markets are themselves blurring and dissolving. The growth of global branding and marketing has forever changed the nature of marketing strategy and contributed to the necessity to take an organizational rather than a departmental view. Global marketing requires a high level of cooperation and alignment along the whole supply chain, and marketing can make no sensible contribution to these decisions if it restricts itself to a narrow view of its responsibilities. General Electric is noted, among other reasons, for its drive to become "boundaryless,"[19] and the 21st century marketer must truly strive for no less.

Morphing Marketing

Marketing faces enormous challenges in the years ahead. Globalization is driving ever more intense competition, and the viability of market positions is everywhere threatened. Yet, as competition intensifies and the weak succumb, surviving firms are correspondingly smarter and more sophisticated. The ability of surviving firms to win via traditional marketing practices will undoubtedly diminish. Indeed, as customers become more sophisticated and better informed, much higher standards of creativity and strategic insight will be mandatory for success. The very foundations upon which many managers' livelihoods rest will be shaken by the profundity of the resulting changes. Yet, whether we look to the practitioner or academe, we find that marketers are often suspect in the eyes of others. Fixed in their paradigms, often frighteningly narrow in perspective, too many seem oblivious to the fact that both the theory and practice of marketing are approaching a crisis. If marketing fails to morph, there may be no marketing! The call is clarion clear: let us hope that marketers rise to the challenge.

Summary

The shift from the material economy to the information economy is the primary driver in the evolution of the key divisions, distinctions, and boundaries that constitute the practice of marketing. We have explored how some of the classic distinctions that are implicit to the traditional practice of marketing are dissolving. Looking within the firm, among firms, between firms and customers, among offerings, and among countries, we charted some of these changes. The generation of informational distinctions (symbols, languages, standards, and processes) will increasingly constitute the primary sources of competitive advantage.