Chapter 27. Anatomy of an Innovation Machine: Cisco Systems

Vijay Govindarajan and Chris Trimble

Introduction

The Innovation Imperative

The twin forces of globalization and the digital revolution are transforming the world economic landscape at an unprecedented rate. Formerly state-dominated economies are becoming globally integrated. As a result, competitors can be anywhere on the globe. Furthermore, new Internet-based technologies are rendering traditional business processes obsolete and at the same time creating opportunities for completely new ventures that threaten long-stable corporations.

No corporate strategy lasts indefinitely, because no competitive advantage can be sustained forever. But in the current environment, characterized by discontinuous change, corporate strategies begin to die on the day that they are born. That's why now, more than ever, the companies that will stay on top over the long run are the strategic innovators—those that regularly introduce completely new or dramatically improved ways of doing business.

Following a decade of focus on reengineering and process improvement, many corporations run supremely efficient operations. One unintended consequence of the aggressive slimming down is that there is little slack time for managers to escape the demands of the present to think about the future. This must be recognized as a vulnerability.

How can CEOs build organizations that simultaneously manage the present and create the future? How can they turn their organization into innovation machines? What does the organization that has the ability to periodically transform an industry with a completely new approach to business look like?

This chapter outlines a framework for implementing the key components of an innovation machine. The framework is illustrated with a description of the innovative efforts of Cisco Systems, the Silicon Valley Internetworking giant, through the 1990s. Cisco has been one of the most aggressive and creative companies in fully leveraging Internetworking technologies to revolutionize core business processes. This chapter concludes with an analysis of the implications of the Cisco experience for other corporations.

Components of an Innovation Machine

An innovation machine consists of two components: a process design and an organizational design. The process design, shown in Figure 27.1, consists of four generic macroprocesses: generating ideas, implementing, modifying, and integrating with the core business. Depending on the idea being implemented, the details within each process might be very different. Nonetheless, to regularly generate strategic innovations, senior executives must manage these processes as components of an overall system.

Figure 27.1. Process design.

They must also energize the innovation processes with an appropriate organizational design, the components of which are shown in Figure 27.2.[1] Organizational design extends far beyond reporting structure. It includes all elements of an organization's social system that influence individual and collective motivations, abilities, and behaviors. These elements, each of which can be directly or indirectly influenced by senior management, include structure, information systems and infrastructure, social interaction patterns, people, leadership, culture, reward systems, and management processes.

Figure 27.2. Organizational design: An organization's social ecology shapes motivations, abilities, and behavior.

Innovation Nomenclature

What Is a Strategic Innovation?

Strategic innovation is quite different from product innovation or technological innovation in that, unlike the latter types of innovation, which are generally the responsibility of corporate research and development departments and often the result of unpredictable random discovery, unexpected meetings, or a sudden creative inspiration, a structured approach to strategic innovation is both possible and necessary.

Strategic innovations transform industries by altering one of the four key elements of the prevailing business model: (1) Who is the customer? (2) What is the value proposition that appeals to the customer? (3) What is the system of business processes that delivers value? (4) What assets or resources must be assembled to enable the business processes, and how is ownership of these resources configured? (See Figure 27.3.)

Figure 27.3. Strategic innovators create new business models by redefining at least one of four business model elements.

Unlike product or technology innovations, which generally rely on a scarce expertise, ideas for strategic innovations might come from most anywhere in an organization. The challenge for CEOs is to energize the identification and execution of the best of the possibilities.

Not All Strategic Innovations Are Alike

Designing an innovation machine starts with describing the desired output. We distinguish two categories of strategic innovations: those that create identifiable new business ventures (those with new customers or value propositions) and those that make dramatic and discontinuous improvements to existing ventures (those that substantially alter the system of business processes and resources).

In addition, it is necessary for designers of innovation machines to characterize their risk tolerance. High-risk innovation machines generate multiple projects in parallel and seek the fastest possible implementation. Low-risk innovation machines focus on one or a small number of projects at a time and emphasize cost or quality of implementation over speed.

Figure 27.4 illustrates the four possible types of innovation machines, which we identify as the Cautious Process Revolutionizer, the Incubator of Process Revolutions, the Cautious Entrepreneur, and the New Venture Incubator.

Figure 27.4. What kind of innovation machine?

Why Study Cisco?

Although the fall of the dotcoms has been sobering, the challenge of reinventing large corporations to take full advantage of the Internet still preoccupies many of today's CEOs. The unrealized potential of Internetworking technologies is tremendous, and we are far from understanding their full impact on the economy. Managing the Internet transformation will likely remain a challenge for CEOs for at least another decade.

Looking for companies to learn from, many executives find inspiration in Cisco. During the dotcom run up, Cisco was often held up as an exemplar of everything that was right about the new economy. True, Cisco's shine was tarnished following a dramatic and unanticipated downturn in its business in early 2001. Nonetheless, its operations have been revolutionized by numerous information technology initiatives, and it remains well ahead of most corporations.

For a while, it seemed as though the Internet was transforming the business world at breathtaking speed, but Cisco's transformation hardly happened overnight. Cisco's innovation machine succeeded steadily over a long time period. In fact, Cisco used email virtually from the day it was founded in 1984, and it began investing in networked software applications for core business functions as early as 1991. More than a decade later, the extent to which Cisco has succeeded in improving its business processes through innovative use of the Internet is impressive. Underlying Cisco's accelerated progress in generating and implementing Internet innovations is Cisco's innovation machine—its well-constructed coupling of an innovation process design and an organizational design. However, Cisco's approach is not appropriate for every company. Cisco's innovation processes are characteristic of the Incubator of Process Revolutions approach (Figure 27.4). Companies that desire a machine producing different types of innovations will require a different approach.

By reviewing Cisco's successful series of initiatives, and then "lifting the hood" of Cisco's innovation machine, we'll see the logic of its design. Then, based in part on articulated concerns from Cisco executives, we'll suggest some alterations to Cisco's approach that would be appropriate for companies seeking to become Cautious Process Revolutionizers, Cautious Entrepreneurs, or Incubators of New Ventures.

The Evolution of Cisco's Use of Internet Technologies[2]

The First E-Marketers?

Cisco was founded in 1984 by two former Stanford University computer scientists, Sandy Lerner and Leonard Bosack. At Stanford, Lerner and Bosack focused their efforts on improving a computing infrastructure consisting of hundreds of distinct computer systems and 20 disparate email systems. After succeeding at piecing together hardware, which connected previously incompatible systems (including running cables through the universities sewer pipes!), the pair decided to start their own company. Email was part of their initial marketing strategy, and they succeeded in building a word-of-mouth reputation among other university computer scientists who were enthusiastic users of early forms of email.

The Growth Crisis

By 1991, under the leadership of CEO John Morgridge, Cisco struggled with a serious growth crisis. With sales of $183 million in 1991, a 2.5X increase over the previous year, Cisco could not hire enough talented engineers to keep up with its customer-service demands. Cisco's customers were implementing complex computer systems on the leading edge of technological development, and their technical support needs were substantial.

This situation persisted over the next several years. Cisco would have severely limited its growth had it not started creatively using information technology to satisfy customer needs directly. Between 1991 and 1996, Cisco implemented the following:

- Provided product information and company information online (1991).

- Added remote diagnostics capabilities into its support package (1991).

- Created online technical assistance bulletin boards (1992).

- Added capability to download software upgrades, and added email customer service (1993).

- Created the Cisco Connection Online, a Website that allowed customers to reprint invoices, check the status of service orders, and configure and price products (1995).

- Added order-status capabilities and interactive training modules (1996).

However, there was more to be done. As of early 1996, even with all of the above functionality, customers still had to make a phone call when they wanted to place an order. Because of the complexity and customizability of Cisco's product line, 25 percent of Cisco's orders were in error when they entered the order queue.

Cisco and e-Commerce

Cisco's next move was to create one of the first e-commerce sites. Its site included an automated product configurator, which would ensure that the set of feature enhancements that customers chose was a compatible combination. By 1997, more than 25 percent of Cisco's orders were coming in over the Internet—by September 2000, the figure was close to 90 percent. Customer satisfaction ratings increased dramatically, and order errors dropped to 1 percent.

Since building this e-commerce site, Cisco has collaborated with a few large customers to take the purchasing process to an even higher level of automation. This involved integrating Cisco's e-commerce site with its customers' purchasing systems. Because no two customers had identical systems, this required the development of customized software for each customer. By 2000, Cisco was working closely with e-commerce software providers and industry standards-setting organizations to provide standardized solutions.

The Cisco Employee Connection

Not all of Cisco's Internet efforts involved automation of communications with customers. In 1995, it turned to routine communications with employees. The motivation was similar—the rate at which Cisco could hire was limiting the rate at which it could grow. To accelerate hiring, Cisco automated routine human resources paperwork. This effort was frustrated by technological limitations—in particular, the lack of the Java programming language.

The next year, Cisco succeeded in automating the expense-reimbursement process. Employees now submit expenses online and get reimbursed by direct deposit within a few days. Subsequently, Cisco retackled the digitization of standard HR forms, and directly integrated hiring and benefits forms into the Cisco Employee Connection (CEC), the company's Intranet. This included the ability for managers to review and sort applicants for specific positions in a number of ways, including by capability and by the competitor they came from. Employee use of the CEC was solidified when Cisco partnered with Yahoo! to create a front page, which included access to such items as weather, sports scores, and headline news in addition to Cisco company announcements and personalizable company directory entries. Senior managers also heavily use internal systems, thanks to impressive management information systems, including a capability to "virtually close" the books within 48 hours, at any time.

The Manufacturing Connection Online

By 1999, Cisco was focusing on digitizing many of its routine communications with suppliers and manufacturing partners. Cisco had increasingly chosen to outsource manufacturing, a further strategy to enable rapid growth. In June 1999, it launched the Manufacturing Connection Online (MCO), an Extranet that enabled partners to have ready access to inventory and order information. In fact, when customers made purchases on Cisco's Web site, its supply and manufacturing partners were notified immediately. The MCO also streamlined communications with Cisco's logistics partners, such as Federal Express, and it eventually incorporated an automated testing capability that enabled products to be delivered to customers without Cisco ever taking physical possession of them.

Unbundling Cisco's Innovation Machine

It is tempting to dismiss Cisco's ability to innovate strictly as a function of its technology expertise. Who but an Internetworking company could be expected to make the quickest work of finding new ways to innovate using the Internet? Its technology expertise and an extremely sophisticated IT infrastructure did, in fact, have a major impact on its ability to innovate.

After a major acquisition in 1993, Cisco faced the technology labyrinth that many corporations currently face. Its infrastructure was ineffective, because there were numerous incompatible systems, no consistent standards, and no centralized data source. In particular, Cisco benefited from a bold and expensive decision in 1994 to completely rebuild its IT infrastructure. The move required a major investment in an Oracle database and resulted in a fully networked, fully scalable, standards-based enterprise system. Because Cisco tackled this problem early in its growth phase, the fix wasn't nearly as difficult as it might have been. Still, to complete the project, Cisco spent roughly $100 million—a sizable percentage of its 1993 revenues of $649M!

Achieving just this enabling condition is a seemingly never-ending headache for many corporations, tied up in a complex and tangled web of disparate, function-specific legacy systems. Cisco was lucky to make the transformation while it was still a small company—just 2,000 employees.

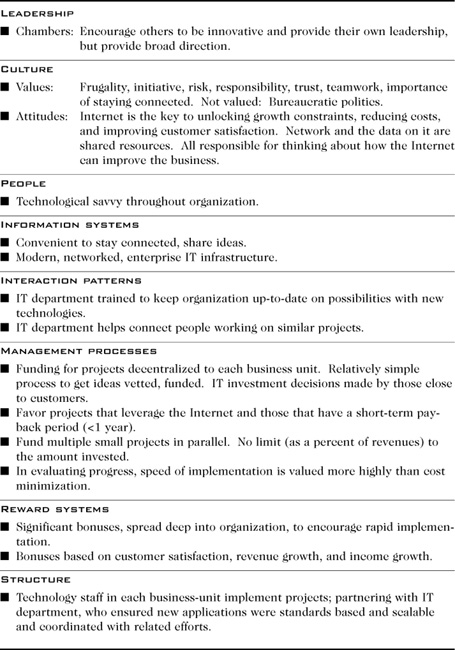

Cisco's success cannot be ascribed to its technology infrastructure alone. In fact, in a survey of 110 senior executives in global corporations, 88 percent indicated that human and organizational barriers were either as limiting or even more limiting than technology barriers in the effort to take full advantage of the Internet. This would suggest that those who seek to replicate Cisco's digital business sophistication need to understand more than the layout of Cisco's servers, databases, and routers. They need to understand its innovation machine. We'll now look at how Cisco's organizational design (summarized in Table 27.1) energized each of the four generic innovation processes.

Cisco's Approach to Idea Generation

Cisco's approach to generating Internet business innovations involved engaging employees to think creatively, building capabilities and knowledge to generate high-quality ideas, and sustaining motivation.

Table 27.1. Cisco's Organizational Design

Generating as Many Ideas as Possible

Every innovation begins with a flash of inspiration. At Cisco, everyone shared in the responsibility for generating ideas to further leverage the Internet, cut costs, and improve customer satisfaction. This sense of responsibility, driven from the top by CEO John Chambers, was a central element of Cisco's culture. Cisco's widely distributed stock options (40 percent of its stock options were spread beyond management ranks), combined with its location in the Silicon Valley, further embedded respect for initiative and risk in Cisco's culture. As a result, there was no shortage of creative thinking.

Channeling Creative Energies

While Chambers encouraged leadership and risk-taking, he felt that unfocused creativity was counterproductive. "You've got to have mavericks...however, the mavericks have to follow within reasonable bounds the course and direction of the company." Too much creativity could lead to an inability to execute.

Cisco focused creativity on the Internet. Because John Morgridge, Chamber's predecessor, had instilled frugality as a core value, Cisco looked for ways to save money. When it did, the first question asked was "What can be automated through the use of the Internet?" Cisco has constantly reinforced the notion that maximizing use of the Internet was the key to unlocking growth constraints, reducing costs, and improving customer satisfaction. (In fact, the Internet is meant to be so central in the operational mindset of Cisco employees that new hires are told that if they have a question, they should seek the answer on the network first.)

Cisco's history suggests a strategy of achieving further focus by sequencing major projects according to the constituents they were designed to serve. The Customer Connection Online was built in the early-to-mid 1990s, followed by the Cisco Employee Connection in the mid-to-late 1990s, followed by the Manufacturing Connection Online in the late 1990s.

Finally, Cisco focused creative efforts by identifying a small number of critical performance drivers: revenue growth, income growth, and customer satisfaction. Because significant bonuses were awarded, employees tended to suggest ideas that they anticipated would have a probable and short-term impact on these metrics.

Assuring High-Quality Ideas

In addition to motivating many ideas in a focused fashion, Cisco's organizational design assured high-quality ideas. Most importantly, the technological savvy of Cisco employees is unparalleled. Because many technologists are more motivated by the opportunity to work on innovative projects at the leading edge of technology rather than on older systems, high-quality ideas were generated by highly motivated employees. Cisco assigned the responsibility of keeping its employees knowledgeable to the IT department.

Quality ideas are often not the inspiration of a single person, but the result of sharing ideas within a community. As such, Cisco executives inculcated a belief in the importance of "staying connected." Because Cisco invested in such sophisticated information systems, it was convenient to find the right people to get involved in new initiatives. The IT department was a "central node" in the social network, and it assisted in making connections between employees.

Sustaining Motivation

Cisco's entrepreneurial spirit could have been squelched had there not been a sensible funding mechanism in place to support new initiatives. Many companies fund IT as a fixed percentage of revenues and manage it as an expense to be minimized. In 1994, Cisco moved away from this conventional approach and initiated what it called the Client Funded Model (CFM). "Client" in this case refers to the IT department's internal customers, the business units. Because funding of new IT initiatives was decentralized, getting creative ideas vetted and possibly funded was more straightforward than it could have been if a long process of approvals been required.

Cisco's Approach to Implementation

Allocating Resources

Given many solid ideas, Cisco managers must select the subset of those that are worth implementing. Because there is so much uncertainty in evaluating innovative project ideas, resources are generally allocated on the basis of judgment, often shaped by thumb rules, values, or the biases of the decision makers.

In many companies, funding authority for Internet initiatives rests within the IT department, which generally has relatively little exposure to customers and tends to focus internally and on costs. By decentralizing the funding process to each business unit, Cisco ensured that the decision makers were as close to the customer as possible. This created a decision-making bias that matched Cisco's balance of emphasis between customer satisfaction and costs. Each business-unit manager was encouraged to make whatever Internet-related investments in new applications that were sensible to improve customer satisfaction and profitability. Further, decision makers were encouraged to manage multiple investments in parallel. To manage risk and complexity of integration, they were encouraged to invest in each project incrementally and to make sure that each project paid off within one year. There were few tremendously large IT implementations going on at Cisco at any one time. In fact, typical projects involved no more than 5 to 10 people.

Implementation Roles

In addition to advising business-unit managers on the prioritization of competing projects, technology experts within each business unit would take a lead role in implementing new applications. They coordinated with the IT department, whose primary role was to ensure that each application followed a specific set of IT standards and was scalable so as to support the company's continued domestic and international growth. Because multiple projects were implemented in parallel, it was critical to coordinate efforts. Also, the IT department was responsible for trying to identify overlaps of functionality among multiple ongoing projects.

Interestingly, at the time the CFM was implemented, the reporting structure was altered such that a new group, Customer Advocacy, managed the IT department. This ensured that as applications were developed, even the IT department maintained a focus on the needs of the customer. As Doug Allred, the SVP of Customer Advocacy, put it, "Every past step that has worked arose from close customer intimacy...from being really well connected to customers and understanding what they are trying to do, and then addressing their needs in the form of what we would now call e-business functionality."

Cisco Culture

Implementation of innovative projects can easily engender conflicts over who gets the credit, or the blame. Cisco constantly reinforces attitudes of trust and teamwork, and maintains a pronounced disdain for bureaucratic politics. Another of Cisco's critical cultural attitudes is that Cisco's network, and all of the data on it, is a shared resource that nobody owns.

Cisco's Approach to Evaluation and Modification

Executives emphasized speed. Software applications with much of the same functionality that Cisco was creating from scratch were being developed and commercialized by enterprise software companies, so competitive advantages were likely to be short lived.

Cisco's approach to funding dictated its approach to ongoing evaluation and modification of innovative projects. Because investments were made incrementally, Cisco managers frequently revisited progress of their initiatives, deciding each time the merit of expending additional resources. Since Cisco's innovation machine produced multiple projects in parallel, frequent reviews were a necessity to keep costs under control.

Cisco's Approach to Integration

Cisco's IT department took on the most critical role in ensuring new applications were integrated seamlessly into the company's operations. To streamline this process, it initiated oversight of projects on day one, providing coordination with overlapping projects and ensuring that a common set of software standards was followed. Without Cisco's sophisticated IT infrastructure, integration of so many parallel projects would have been extremely difficult. As mentioned previously, the IT department's reporting relationship—to the Customer Advocacy group—helped create a customer-oriented mindset that influenced how new applications were integrated.

Learning from the Cisco Experience

Limitations of the Cisco Approach

While Cisco's record of innovation is impressive, executives within Cisco haven't let themselves become complacent about whether or not their innovation machine will continue to serve the company well in the future. Amir Hartman, formerly the managing director in Cisco's Internet Business Systems Group, described the angst: "What was innovative yesterday in many ways becomes the standard way of doing business tomorrow. You've got software packages and applications out there in the market that have ninety-plus percent of the functionality of the stuff that we custom built for our own company. So...how do we maintain and/or stretch our leadership position vis-à-vis e-business?"

Of greater concern to some is the type of innovations that the system is generating. Because of its relentless focus on customer satisfaction and a bias for making investments in initiatives with short-term paybacks, Cisco may be passing over opportunities for even more revolutionary efforts. Further, most of Cisco's initiatives focus on only one aspect of its business system—business processes. (See Figure 27.3.) Cisco is a leader in making business processes more efficient simply by automating routine information flows. The Cisco Connection Online, the Manufacturing Connection Online, and the Cisco Employee Connection all focused on exactly that—automating recurring transactions between Cisco and its three most significant constituencies: customers, production partners, and employees.

Innovations in the other three aspects of Cisco's business system are not as easily identified. True, Cisco's initiatives clearly enhanced its existing value proposition, but it is a stretch to say that Cisco used the Internet to create entirely new products and services or to reach entirely new customer segments. There were no "Internet startups" incubated at Cisco.

Although Cisco is an example of a company that outsourced and coordinated over the Internet, the outsourcing approach existed before the Manufacturing Connection Online—a system that simply streamlined existing operations. Cisco had the luxury of being able to implement its supply-chain Extranet when it was clearly the most powerful player in the chain. Had this not been the case, it might have found it much more difficult to get its suppliers and manufacturing partners to adapt their business processes to Cisco's Extranet.

The challenge for vertically integrated manufacturers to transition to a more "virtual" structure through the use of B2B commerce technologies would clearly require a different approach, one that involves designing applications in close partnership with supply chain partners—something Cisco admits it is still figuring out how to do.

These observations are not intended to detract from Cisco's tremendous level of accomplishment in using the Internet. Executives attempting to turn their organizations into innovation machines must decide if the output from Cisco's machine is what they require.

Building Your Innovation Machine

Determining the best design of your innovation machine starts with choosing an approach to innovation (see Figure 27.4). Do you desire to be like Cisco, an Incubator of Process Revolutions? Or is one of the other quadrants in the matrix more sensible for your organization? Studies of other companies will allow more concrete conclusions, but based on the above analysis, adapting Cisco's innovation machine in the following ways for other quadrants appears appropriate.

Incubating New Ventures

The most revolutionary ideas are often generated by creating interaction between people who don't normally cross paths. At Cisco, the IT department was the "marriage broker," who looked for related initiatives throughout the company and sought to improve them by getting the technologists to work together. This approach seemed to keep Cisco ahead of the game in terms of automating business processes. But different types of interactions may have generated more grandiose ideas. For example, ideas for new startups are more likely to be generated by linking business managers, both inside and outside the company, to each other.

Other components of Cisco's innovation machine may not be ideal for companies interested in encouraging entirely new ventures. For example, the IT department may play a less central role, with heavier leadership burden on managers who regularly interact with customers or potential customers. In addition, for more revolutionary ideas, the ease with which the new systems will integrate with existing systems and scale is a much lower priority.

Furthermore, Cisco's focus on customer satisfaction and frugality are likely to discourage revolutionary ideas, which often cost too much initially and don't yet inspire interest from mainstream customers. It follows that customer satisfaction is also not an appropriate performance measure. Furthermore, the best funding mechanism for generating new business models is unlikely to involve managers who have a full-time responsibility for existing business units. Such ideas may be best evaluated by a separate corporate ventures group that is encouraged to take bigger risks.

Generating Process Innovations More Methodically

At Cisco, speed of implementation was heavily emphasized. This was reflected in its funding approach and decentralized style. Of central concern to Mr. Hartman is whether or not the company has simply become too large for this system to work. As the company becomes bigger, the task of coordinating the various initiatives becomes much more difficult. As a result, implementation times tend to rise. Costs also rise because of the increased likelihood that multiple initiatives are solving closely related problems.

For the largest corporations, it may not be sensible to generate so many Internet-related business initiatives in parallel. Centralization of the innovation process, at an earlier stage in the development of initiatives, is key. This will slow things down, but it is also likely to avoid excessive costs as duplicative efforts are minimized. To the extent possible, all employees should be energized in the idea-generation process, but this is difficult when the immediate next phase, receiving funding for the idea, requires a more centralized approval process.

Conclusion: So You Want to Be Like Cisco?

Having considered your strategic priorities, suppose you conclude that you want an innovation machine like Cisco's. This is an admirable choice! After all, as many corporations learned from failed dotcom ventures, revolutionary ideas only succeed sometimes, and staying ahead of the game in terms of costs and efficiency can be a critical source of competitive advantage.

As a caveat, keep in mind that it can be a short-term advantage. It lasts only until enterprise software companies are able to build the same functionality into the packages that they offer and competitors successfully implement the new functionality. Cisco was able to stay ahead of software vendors in part because of its high level of technological savvy at all levels of management. Industries that have difficulty achieving this level of savvy will win competitive advantages of even shorter duration. (On the other hand, every industry has peculiarities that will never be included in software packages—so there is some subset of business activity where an innovation machine like Cisco's can generate advantages.)

Imitating Cisco's innovation machine won't be easy. For starters, getting through the process of updating computing infrastructures and installing enterprise software solutions can easily take 2 or 3 years, and that just provides the technology foundation. Furthermore, changing attitudes towards the importance of the Internet is much harder for an existing corporation than a growing one. Mature corporations turn over just a small fraction of their employee base each year, while in startups there is more opportunity to create and recreate culture as fresh and impressionable minds are rapidly hired.

Cisco was a great story of the 1990s, and its approach to leveraging the Internet is a sharp illustration of how a process design combined with the appropriate organizational design generates impressive innovations. However, imitators should think carefully about the type of innovation they are trying to create and should assemble the components of their innovation machine with the desired output clearly in mind.