Chapter 3. Developing and Enhancing Popular Programs and Services

“As you may be aware we received great news from the government after I dropped our petition in to 10 Downing Street. They have now promised to spend £280 million to improve school dinners across the country. This is a huge victory for all dinner ladies, parents and most importantly for the kids to whom it matters the most. This outcome is entirely the result of your sheer commitment to support this campaign, sign the petition and to encourage a fellow 270,000 to sign as well so ... CONGRATULATIONS AND BIG LOVE TO YOU ALL!! ... Jamie O xx”

Jamie Oliver, a celebrity chef in the U.K.

Posted April 13, 2005 on www.feedmebetter.com

One of the most important marketing functions in the commercial sector is that of product management. It is just as important in the public sector, especially for those of you who are program managers. Some say product management first appeared at Procter & Gamble in 1929, when one of the company’s soaps, Camay, was not doing well, and a young executive was assigned to give his exclusive attention to this product alone.1 It worked, and the company as well as other consumer product industries created the role of the product manager, who was responsible for developing competitive strategies for the product, preparing annual marketing plans, working with advertising agencies, supporting the product among the sales force and distributors, gathering continuous intelligence on the product’s performance and customer satisfaction, and signaling any opportunity for new product development or needed improvements to existing ones.2

In this chapter, you explore basic definitions and components of an agency’s product and then focus on product management functions most relevant in the public sector, those of developing and enhancing programs and services.

You begin with an inspirational story, selected this time to illustrate the need for and impact of product improvement, depicting how governmental agencies can sometimes be nudged to make these changes and how smart it can be for you to pay attention and respond to these wake-up calls. You also consider the power of one, in the citizenry as well as in the government, to create social change.

Opening Story: School Meal Revolution in the United Kingdom

The International Obesity Taskforce estimates that one in ten school-age children, a total of 155 million worldwide, are overweight and that 30 to 45 million of these students are classified as obese.3 Significant economic as well as social costs are associated with this epidemic. In the U.K., for example, it is estimated that obesity and diet-related illnesses in the total population are costing the National Health Service more than $12.7 billion annually.4 To underscore the problem in this country further, recent surveys show that nearly one in five British children is obese and 40 percent of teenage girls are iron-deficient.5

Where do governmental agencies begin to tackle this one? And what does marketing have to contribute? The following story from the U.K. suggests that a marketing mindset, especially one with attention on program improvement, can contribute a lot.

Challenges

In March and April of 2005, newspaper headlines wrapped the globe; the world intrigued with what had happened at 10 Downing Street on March 30th.

“Jamie gives school meals the wooden spoon”6

The Sydney Morning Herald, March 24, 2005

“TV chef transforms U.K. school meals”

United Press International, March 22, 2005

“Chef’s Naked Truth on School Food”

The Australian, March 22, 2005

“Chef whips U.K. school cafeterias into shape”

The New York Times, April 25, 2005

The “warrior” drawing worldwide attention was a 29-year-old celebrity chef in London with a television program, a best-selling cookbook, a charity foundation that supports unemployed youth—and a mission. He wanted to replace the fatty, salty, greasy, processed, sugary food served in dining halls in Britain’s schools (food he called rubbish) with freshly cooked, nutritious meals, ones loaded with natural ingredients, fruits, and (hidden) vegetables. His project, Feed Me Better, captured the attention of a country apparently growing fatter and unhealthier because of its poor diet and sedentary ways and a government wanting to do something about it.7

His quest for change and crusade for new rules began with visits he made to schools on behalf of his charity where he discovered, as described by The New York Times, “lunches virtually inedible, made up of dishes like gristly sausage rolls and frozen shapes calling themselves fish, chicken and pork. Baked beans and French fries were ubiquitous; vegetables were virtually extinct.”8 He was quoted as asking, “Who’s in charge of this?”

Strategies

Over the next year, Jamie Oliver acted more like a marketer than a chef, one with concrete goals (changing the rules and increasing resources), a clear sense of the target audience (the school children themselves), his key influencers (the dining hall staff called Dinner Ladies), and his best potential partners (teachers and parents). He had a keen understanding of the barriers he would need to overcome (the good taste of bad food and the systems in place to produce it) and benefits he would need to amplify (health and better school performance). He developed and implemented an integrated promotional strategy utilizing most media vehicles and types, including mass media, printed materials, special events, an award-winning Web site, and a compelling direct response campaign to gather petition signatures.

He even started with a pilot project, persuading one school district in London to give him a chance to demonstrate that school menus could be healthier without costing more. A New York Times article posted on the International Herald Tribune Online described a few surprises for the pilot: “The cooks, used to dealing mainly with frozen nuggets, balked at the extra work involved in preparing things like seven-vegetable pasta sauce from scratch.” One little boy, tasting what he said was his first-ever vegetable, threw up on the table.9

Oliver then did what any good marketer would do and resorted to desperate tactics designed to persuade target audiences, including dressing up like a giant corn-on-the cob, singing a pro-vegetable song, giving out “I’ve tried something new” stickers, even “tossing a chicken carcass into a blender along with bits of skin, fat and bread crumbs, whizzing it around, and showing off the result: stomach-turning mush that, when shaped and cooked, could pass for the nuggets they had been eating.”10 In the end, he won the loyalty of the children, the praise of the teachers and parents, and the attention of millions of viewers of his four-part television series who were watching, including one Prime Minister Tony Blair.

Those viewers who were inspired to find out more or do something for their own school could visit the Feed Me Better Web site where they were provided an arsenal of options to start a revolution of their own: information on how school meal contracts work, status of schools in their district regarding efforts to improve meal nutrition, details on how the pilot school district was able to change things, factoids about school meals, access to recipes that had been featured on the television series and at the pilot school district, and a Feed Me Better starter pack providing ideas on getting school involvement with classroom learning activities. Visitors were encouraged to lobby their elected officials to increase the minimum amount of money spent per child per day, clarify current nutritional standards for school dinners to create more effective inspections and to raise standards, make nutritional health a part of the national curriculum for all primary schools in England and Wales, and ensure that the needs of big business are not put before those of the health of the children (see Figure 3.1). For six weeks in early 2005, visitors were encouraged to sign a petition to be delivered to 10 Downing Street.

Figure 3.1. A factoid appearing on the Feed Me Better Web site

Rewards

Outcomes from the pilot were encouraging, with teachers telling Oliver that their students were more alert and able to concentrate better and that behavior improved markedly among those who had opted for the healthier new dishes.11 Parents reported their children were having fewer asthma attacks.12 A promise came from the Greenwich Council (the pilot school district) to replace fast food with fresh food menus for 20,000 students and from the caterer that they would be taking Turkey Twizzlers off the menu,13 an item that rocked viewers of the television series when they found out it contained one-third meat and water, pork fat, rusk (re-baked sliced white bread), colorings, and flavorings.14

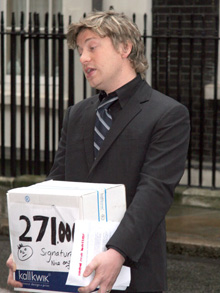

On the morning of March 30th, 2005, Jamie Oliver met with Tony Blair and presented a petition with more than 271,000 signatures, ten times more than the 20,000 he thought he would get when he started out six weeks earlier (see Figure 3.2). Considered a wake-up call and mandate for reform, soon afterward Blair announced that he had set aside more than £280 million, about $536 million, to improve school meals.15

Figure 3.2. Chef Jamie Oliver delivers a message for school cafeteria reform from 271,000 UK citizens to 10 Downing Street. (Photo © Tom Hostler 2005)

This national commitment received considerable press and praise, including the following quote in the British Medical Journal: “Jamie Oliver has done more for the public health of our children than a corduroy army of health promotion workers or a £100 million Saatchi & Saatchi campaign.”16

Perhaps the most public display of respect for Oliver’s work came from a reader of The Daily Telegraph who wrote in about the effort asking, “Could Jamie Oliver have a word with the airlines?”17

Product: The First “P”

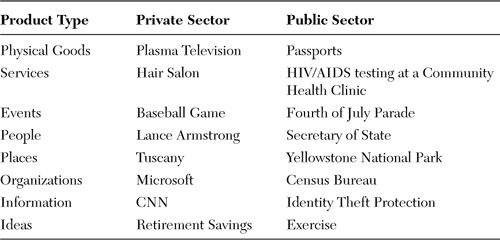

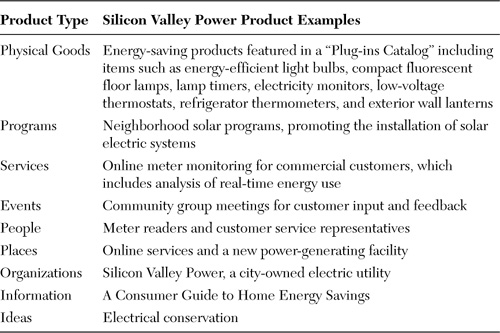

Product, as a term in the public sector is not familiar to many who are more likely to associate the label with tangible goods in the private sector, ones such as soap and tires. In marketing theory, however, this term is broadly interpreted and refers to anything that can be offered to a market by an organization or individual to satisfy a want or need. It does, of course, include physical goods and services, but it also refers to an array of additional organizational offerings being “sold,” including events, people, places, the organization itself, information, and ideas. Parallels between the private and public sector are drawn in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1. Examples of Product Types in the Private and Public Sectors

In addition to product types, a few traditional terms are also worthy of distinction:

• Product Quality refers to the performance of the product (e.g., accuracy of an HIV/AIDS test).

• Product Features refers to a variety of product components. The number of days (or hours) it takes for an HIV/AIDS test result is a product feature, with rapid testing considered by many a welcomed new option. At a national park, features would include items such as electrical hookups for recreational vehicles, nature hiking trails with plant labels, boat launches, and information kiosks.

• Product Style and Design are important product components as well, with style relating more to tangibles (e.g., the aesthetics of an airport’s retail store corridor) and design referring more to functionality and ease of use of the product (e.g., the location and traffic patterns of retail shops relative to departure gates).

• Product Line refers to a group of closely related products that are offered by an organization, ones that perform similar functions but are different in terms of features, style, or some other variable.18 A water utility, for example, may offer or promote a variety of water-saving devices including low-flow toilets, low-pressure showerheads, rain barrels, cisterns, and soaker hoses.

• Product Mix consists of all the distinct product items that an organization offers, often reflecting a variety of product types, ideally selected to support the agency’s mission and strategic objectives. For example, Silicon Valley Power, a city-owned electric utility, has a strategic platform developed in cooperation with the City of Santa Clara Government and City Council that not only includes electrical power generation and improvements in transmission and distribution but also embraces careful monitoring of energy use “so that no resources are wasted.”19 Their product mix appears aligned with this platform and is designed to provide a host of products that will assist as well as motivate both residential and commercial customers to conserve energy (see Table 3.2 and Figure 3.3).20

Table 3.2. Product Mix for Silicon Valley Power, City of Santa Clara

Figure 3.3. Cover of product catalog

Developing an array of products such as those offered by this utility has advantages and implications for many organizations in the public sector, if not all. Perhaps most important is the reality that customers of any given agency have a variety of wants and needs, and most would consider it unlikely that they could be met satisfactorily with a single offering, or even a single type of offering. In their book Reinventing Government, Osborne and Gaebler describe the implications and likely future for product mix decisions in the public sector:

“A time will come when people won’t believe that the poor in America once had to visit 18 different offices to get all the benefits to which they were entitled. And a time will come when people won’t believe that parents in America once could not choose the public schools their children attended. By the evidence piling up across this land, that time will come sooner than most of us think. In a world in which cable television systems have 50 channels, banks let their customers do business by phone...one-size-fits all government cannot last.”21

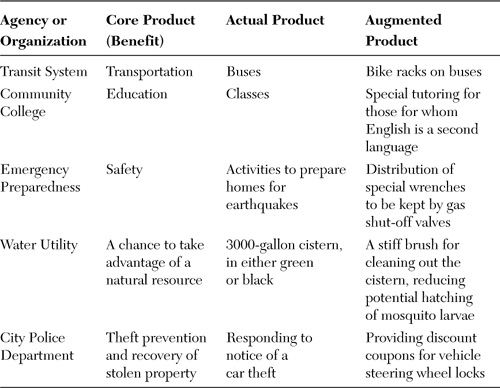

Product Levels

Traditional marketing theory identifies three levels of a product, a model acknowledging that from the customers’ perspective, a product is more than its features, style, and design. It must include the bundle of benefits that customers expect to experience when they buy and use the product. This platform is helpful in conceptualizing and designing the product strategy because it stimulates discussions and leads to decisions that create the foundation for the offer.

The core product is seen as the center of the total product. It consists of the major needs that will be fulfilled, wants that will be realized, and problems that will be solved by consuming this product. It is the real reason the customer is buying the product and is determined by the customer’s answers to such questions as, “What’s in it for me to buy this product?” You’ll want to keep in mind that people don’t buy drill bits. They buy quarter-inch holes. They don’t buy cosmetics. They buy hope. They don’t buy a room they can rent while away from home. They buy a good night’s sleep. And they don’t buy stamps. They buy delivery of a card to Mom in time for Mother’s Day.22

The actual product is more obvious and includes aspects such as product quality, features, packaging, style, and design. It also includes any brand name used. Ideally, as always, each of these decisions is made based on customer needs and preferences, taking into consideration alternative (competing) products.

For illustration, consider the features of a service called E-ZPass, an electronic toll collection service operating in several states on the East Coast of the United States. When a prepaid account is established, customers receive a small tag containing an electronic chip that they attach to the windshield inside their car. Each time a customer accesses a toll facility where E-ZPass is offered, that customer can use an E-ZPass lane. An antenna at the plaza reads the vehicle and account information, and the appropriate toll is then electronically debited from the prepaid account, eliminating the need to slow down to find and deposit cash, tickets, or tokens. A record of transactions is included in a periodic statement.23 This innovation has helped to improve traffic flow and reduce the needless burning of fuel in cars that are waiting to pay a toll.

The augmented product includes additional features and services that add value to the transaction beyond customer expectations. Most consider this product level an optional one, with some even labeling it as the “bells and whistles” category. You don’t have to have it. In many cases, however, it can be the key differentiator from the competition (e.g., a community college that offers special tutoring for those for whom English is a second language). For campaigns related to public behavior change (social marketing), it may be exactly what is needed to provide encouragement (e.g., a walking buddy match for a college campus physical activity campaign), remove barriers (e.g., a map of jogging trails), or sustain behaviors (e.g., a daily journal for recording physical activity).

Table 3.3 provides a variety of examples illustrating these product levels in the public sector.

Table 3.3. Product Levels with Public Sector Examples

As a way to summarize the three product levels, note all the possible options available in developing an HIV/AIDS testing product platform.

At the core product level, potential benefits of testing to highlight for target audiences include increased peace of mind that comes from knowing one’s HIV status, positive or negative; an opportunity to be responsible for personal actions by avoiding spreading the disease to others; if pregnant, getting early treatment for an unborn child; and potential for a longer life and a higher quality of life, as early medical treatment may contribute to both. There are also several options for actual products, the tests themselves: blood tests, oral tests, urine tests, rapid tests, home test kits, and tests “packaged” as part of an annual checkup. And finally, potential augmented products (which as mentioned earlier may increase the likelihood that someone gets tested) would include services such as counseling, support groups, referrals to medical treatment for HIV, and recommendations for protecting oneself in the future.

Decisions among options at each of these product levels are based on the unique profiles of target audiences—their demographics, geographics, current behaviors, barriers, and motivators. Assume, for example, that the target audience for an HIV/AIDS testing campaign is pregnant women who may be at risk for HIV/AIDS. A product strategy for this market might be designed as illustrated in Figure 3.4.

Figure 3.4. Product platform for an HIV/AIDS testing campaign

Product Development

A systematic approach should guide the development and launch of new programs and services in the public sector. The challenge is to remain cognizant of important steps without becoming bogged down by them and to allocate sufficient, but not excessive, resources to the process.

Kotler and Armstrong suggest eight major stages in new product development, illustrated in Figure 3.5 and described in the following section.24

Figure 3.5. Major stages in new-product development25

1. Idea Generation. Ideas for new products can come from a variety of sources including employees, special interest groups, elected officials, internal committees assigned to new product development, other governmental agencies, and of course, current and potential customers (e.g., the petition for new menus and ingredients in school meals delivered to Tony Blair, signed by 271,000+ citizens). They can be generated in a variety of ways, including brainstorming sessions, suggestion boxes, and annual awards for new ideas. It is also worthy of attention for you to note that in the private sector, important sources for new product ideas include the company’s distributors and suppliers as they have that critical frontline perspective of the marketplace. This applies to the public sector as well (e.g., ideas that contract firms have for shortening lines at airport security). Many organizations maintain a competitive watch, allowing them to take advantage of insights that others may have on customer needs and to be prepared for new competitive offerings. When searching for ideas, Osborne and Gaebler would probably advocate that we take an anticipatory approach, searching as much (if not more) for programs and services that are preventive in nature (e.g., ways to prevent wildfires) as we do for ones that are curative in nature (e.g., new firefighting equipment).26

2. Idea Screening. As ideas are presented or discovered, your task now, as Kenny Rogers sings, “is knowin’ what to throw away and knowing what to keep.”27 Criteria for evaluating ideas are varied but must include references to the agency’s mission, goals, and resources as well as the unfulfilled wants and needs of customers, zeroing in on those ideas that best meet both requirements.

A state’s taskforce on litter prevention, for example, may be considering numerous potential efforts to reduce and prevent littering: new litter bags with Ziploc tops to address customer concerns with spillage from drink containers; drive-up deposits for litter at truckers’ weigh stations, eliminating the need for special stops; distribution of smokeless car ashtrays for cigarette butts; or working with a contractor to develop new and improved cables to help secure pickup loads. In the screening process, the idea of new litter depositories for truckers might emerge as the best idea to take to the next level as it addresses a customer need, a major litter problem on roadways, and because it is within the purview of the agencies on the taskforce to make happen.

3. Concept Development and Testing. At this stage, you will create a detailed description of the idea, envisioning potentials for each of the three levels of the product platform: options for potential customer benefits, features and design elements for the actual product, and ideas “for extras” comprising the augmented product. Concepts are then tested with the target audience, first to see whether the concept is of interest and then to explore reactions to initial ideas and suggestions for increased appeal.

For a city water utility planning to subsidize and sell rain barrels to interested residential customers, for example, focus groups might be conducted to determine whether the major perceived benefit of the barrels is “a chance to make use of a natural resource” or whether it is more appealing as “a way to save on water bills” and whether a recycled Greek olive barrel is more or less appealing than a new plastic barrel.

4. Marketing Strategy. You now develop an initial marketing strategy that describes preliminary thoughts regarding target markets, planned product positioning, and additional marketing mix elements (pricing, distribution, and promotion). It will also project potential market sales, which in the case of public sector agencies refers more to anticipated utilization rates or participation levels.

A marketing plan for a new online service developed in 2003 in Washington State designed to divert unwanted building materials and large household items from landfills highlights steps in this process. The service was developed by the state’s Department of Ecology, and a preliminary marketing strategy was outlined by a planning group that included representatives from participating counties around the state. Primary target markets for posting and purchasing building materials were identified as construction and demolition contractors, and for large household items, people having garage sales were among those targeted. The service was positioned as an inexpensive and easy way to dispose of materials and large household items that were perhaps headed for the dump but really “too good to toss” (see Figure 3.6). All items posted were to be priced under $99, and media channels were anticipated to include, among other things, mailings to registered contractors, posters, newsletters, and utility bill inserts.

Figure 3.6. Logo used for Washington State’s online materials exchange program28

5. Business Analysis. Evaluating the business attractiveness of the proposal is your next task, focusing on calculating total anticipated costs for the program and weighing these against any monetary and nonmonetary benefits to the organization.

A new youth tobacco Quitline, for example, might have made it to this stage in the development process because a state Department of Health could have seen it as meeting both a market need (teens who are smoking and want to quit) and an organizational goal (reduction in youth tobacco use). Experience with an adult Quitline may have helped planners to develop a preliminary marketing strategy. A cost-benefit analysis, however, might cause rethinking as the costs for new protocols, extended hours preferred by the teen population, special staff training, and a separate toll-free number are actually determined. When weighed against the actual number of youth anticipated to call, the projected cost per “quit” might be seen as too costly. An alternative idea to develop a youth-dedicated Web site with links to counselors, an idea that was perhaps tabled in the screening stage, might be reexamined, especially after factoring in a finding that more teens were likely to visit a Web site than to call a phone center.

6. Product Development. To this point, your new product idea has existed only in words, perhaps illustrated with a few graphics. After passing the business analysis, steps are taken to develop a prototype of the service or physical object, sometimes with more than one version. Prototypes are then tested for functionality, thereby ensuring quality performance.

The water utility mentioned earlier that was developing a program to distribute rain barrels might order and assemble several manufacturer options and select special parts for hookup and mosquito protection. It wouldn’t be unusual then for a program manager or someone on staff at the utility to try out the options in their own backyard and report back on which ones worked best and any flaws or cumbersome features that need to be resolved.

7. Test Marketing. This step, thought of by some as a pilot, takes the new product to a more realistic market setting. This gives the marketer a chance to test and then refine the target market, the offer (product, price, and place), and promotional strategies. In addition to improving chances for success (market adoption) when the product is launched on a broader scale, this effort may also help reduce costs of rollouts by pointing to strategies that might be eliminated or improved going forward.

This approach might be used for a campaign to promote smoke-free homes and cars where children are present, utilizing a packet of materials sent home from school to parents. In the packet might be several items including a refrigerator magnet, pledge card for a smoke-free home, and air freshener for a car with statistics regarding the effect of secondhand smoke on children in cars, with a reminder message to smoke outside. Of interest at the end of the pilot phase would be whether parents actually put the magnet on the refrigerator, signed and posted the pledge card, and hung the air freshener from the rearview mirror. If evaluation showed, for instance, that very few used the air freshener, or that the air freshener was interpreted by some to mean it was okay to smoke in the car, this budget item could be eliminated upon campaign rollout.

8. Commercialization. The organization now decides whether to launch the new program into the market and if so, when and where.

In the public sector, the AMBER Alert System is a relevant example. The program first started in Dallas-Fort Worth, Texas in 1996 when broadcasters in the area teamed with local police to develop an early warning system to help find abducted children, a legacy they created for a 9-year old girl, Amber Hagerman of Arlington, Texas, who was abducted while riding her bicycle and later found murdered. AMBER (America’s Missing: Broadcast Emergency Response) Alerts are emergency messages broadcast when a law enforcement agency determines a child has been abducted and is in imminent danger. The broadcast provides information on the physical description of the child and anything known about the abductor’s appearance and vehicle. Nine years later, in February 2005, the Department of Justice announced that Hawaii became the 50th state to complete its statewide AMBER Alert plan (see Figure 3.7).29

Figure 3.7. The AMBER Alert program that started in one state is now in all 50.30

Product Life Cycles

When launched, you hope your product will then enjoy a “long and happy life.” Unfortunately, this is rarely the outcome. In fact, as with new parents, the work has just begun. To deal with this issue conceptually, marketers often refer to a theoretical model called the Product Life Cycle, illustrated in Figure 3.8, which identifies four distinct stages that the product may go through: Introduction, Growth, Maturity, and Decline. Corporate marketing and brand managers are most interested in the sales and corresponding profits at each stage. In the public sector, participation and usage levels are more relevant than sales; retained earnings are more applicable than profits. The usefulness to program managers in the public sector is that each phase has its own unique set of characteristics and challenges and therefore implications for strategic actions. Signals that a product is at a particular “stage in life” are described in the following section, as are recommended strategies to employ.31

Figure 3.8. Product Life Cycle Theory32

1. Introduction. As might be expected, this first phase is most often a period of slow adoption and participation rates as the product (program or service) is introduced in the market. You and others should not be surprised if costs are high relative to outcomes. In fact, this should be anticipated, and expectations for this should be established ahead of time with key publics, including administrators and funders. At this launching stage, resources need to be focused on informing citizens of the new offering and on getting them to try it, an effort often requiring promotional spending and additional staff time to get the word out (e.g., the promotional efforts necessary to educate people about AMBER Alerts and the appropriate and helpful citizen response).

2. Growth. This stage is marked by more rapid market acceptance, thus improving somewhat the rate of return on promotional and staff resource allocations. Ideally, it is an exciting time, as early adopters spread the word and the early majority follows. To support this momentum, turn your focus now to ensuring that the offer meets customer needs and expectations, including product performance (e.g., a new rapid transit system arriving and departing on time) and properly functioning distribution channels (e.g., a Web site for information on transit schedules). For managers, the goal at this stage is to sustain rapid growth by continuing to build brand awareness and loyalty. As noted in Figure 3.8, expenditures of resources are still likely to be high relative to “sales” because upfront development costs are still being “paid for” (e.g., costs for developing the light rail system in the first place).

3. Maturity. At some point, the rate of sales growth will slow, and the product will enter a stage of relative maturity, a stage that can and often does provide high profitability when upfront developmental and marketing costs have been returned. Several factors may have contributed to the leveling of sales, including the possibility that the most likely potential customers for the current offer have “already bought it,” meaning they are currently using a service (e.g., community transit) or participating in a program (e.g., recycling). You can try several potential modifications to current marketing strategies to sustain product viability: market modification, in an attempt to appeal to new markets for existing products; product modification, an effort to increase usage/sales among current customers and/or to attract new ones; or other marketing mix modifications including changing pricing structures, distribution channels, and/or promotional efforts.33

At a city that has a Port Authority managing an airport and a seaport, for example, “sales” are measured and revenues are impacted by the number of passengers arriving and departing at an airport, the number of cargo containers handled at the seaport, the number and value of leases for dock space, and the number of cruise passengers traveling through terminals. At a mature stage, usage and correlating revenues might be sustained, even boosted somewhat, by product modifications (e.g., upgrades to terminals), market modifications (e.g., appealing to recreational boat owners for leasing available dock space), pricing (e.g., requiring vendors at airport terminals to have street pricing, where prices charged must be comparable to those found outside the airport), distribution channels (e.g., availability of online reservations for cargo containers), or promotional strategies (e.g., soliciting the business of international cruise lines or visiting Pacific Rim companies to pursue trade opportunities).

4. Decline. For a program at this stage, sales are on a downward drift. Most options for growth have been explored and tried at the mature product stage. The question that you wrestle with now is whether to withdraw the program from the market or to just scale it down. Decisions will rest on a number of factors, including whether there is continued funding for the program in spite of participation levels (e.g., federal grants for community-based physical activity programs); whether assessments indicate that the decline is temporary due to extraordinary circumstances (e.g., military recruitment during a time of war); or whether the agency, in spite of participation levels, has a mission or mandate to continue to provide the offering (e.g., free immunizations).

You will want to note that this cycle and bell-shaped curve is only conceptual in nature and that some products are introduced and then die quickly, some have only a short growth spurt, others enjoy a long mature stage, and a few thought to be slowly declining are suddenly “brought back to life.”

Product Enhancement

Though product enhancement activities are similar to those conducted when developing a new product, it is worthwhile to recognize this as a distinct and important effort, one with a role for marketers, or at least those with a marketing orientation. The role is to sense customer satisfaction levels with current offerings and to help determine what product improvements would increase satisfaction and product performance.

A school reform effort in Philadelphia, one of the nation’s largest school districts, provides an inspiring example.

James Nevels, Chair of the Philadelphia School Reform Commission, shared an inspirational story that appeared in Forbes Magazine in March 2005. When he started chairing the commission in 2002, he led the district in defining their customers exclusively as the 200,000 children they served, and the challenge was to improve their learning (in marketing terms, the product’s performance).

Efforts to improve performance included some that might be expected, such as standardizing curriculums so that all students would learn what had been determined as most crucial for success and would make transferring between schools easier. Elementary school students began spending two hours a day on reading and 90 minutes on math, double what they spent before. Less expected was the initiation of benchmark testing every six weeks in elementary and middle schools and every four weeks in high schools, helping teachers to decide which students needed more dedicated time for a subject and which ones were ready for advanced instruction. They reduced class sizes and added academic coaches.

And there were unexpected, bold strategies as well, ones addressing the learning environment. They adopted one of the toughest codes of conduct in the nation, one that extended to acts committed after school hours and off school grounds: “If a bully beats up a classmate at a bus stop on a Saturday, we will suspend him. In the past he wouldn’t even have received a reprimand. A high schooler who damages property or commits an assault will be removed from his neighborhood school and sent to an alternative education high school.” In addition, they placed a district police officer in every school and invested millions in metal detectors and video cameras.

The results indeed signaled improved performance. After two years of reform, Nevels reported that between 2003 and 2004 the percentage of the city’s public school students scoring “proficient” or better on state exams increased an average of eight percentage points in reading and math for fifth graders and eleven points for eighth graders.34

Packaging

As mentioned earlier in the chapter, decisions regarding the actual product may include those related to packaging, typically referring to the container or wrapper for the product, its contents, and labeling and printed information. This may include the product’s primary container, any secondary package that is thrown away when the product is about to be used, and the shipping package. Traditionally, the primary function of the package was to contain and protect the product. Nowadays, however, it is considered an important marketing tool as well. Consider, for example, the distinctive and elaborate packaging of a condom product in Nepal.

In collaboration with His Majesty’s Government of Nepal Ministry of Health and Department of Health Services (HMG), Population Services International (PSI)/Nepal developed and implemented a campaign promoting the use of the Number One condom, launched in April of 2003. In order not to stigmatize the brand, it was decided that the brand should be established broadly across the youth segment before focusing on the target population—high-risk and vulnerable groups. The packaging colors (fluorescent yellow), hip style, and bold graphics are certainly aligned with this strategic intent (see Figure 3.9). Distribution channels for the condoms included traditional outlets such as pharmacies and drugstores and more non-traditional ones such as community health fairs, dance restaurants, and massage parlors. In the first seven months of distribution, 3.51 million Number One condoms were sold.35

Figure 3.9. Outer package for PSI condoms distributed in Nepal in cooperation with His Majesty’s Government of Nepal

Summary

You can revisit the basic principles and theories regarding product development and improvement presented in this chapter by taking a walk (in time) around the Louvre, a crown jewel of the French government.

Located in Paris and managed by the French state, the Louvre is one of the largest and most famous museums in the world. As a former residence of the kings of France, it was not even originally intended to become a museum. The museum that now inhabits the Louvre Palace has existed for over two hundred years and was first opened to the public in 1793, consisting primarily of the former royal collections of paintings and sculptures. Its product types today are varied and include Asian, Egyptian, Greek, and Roman antiquities; sculptures from the Middle Ages to modern times; furniture and objects of art; and of course, paintings representing all the European schools. The product line of paintings alone includes some of the most famous in the world, works of artists like Renoir, Rembrandt, Rubens, and Leonardo da Vinci.

Consider its product levels. At the core, visitors are most likely seeking and will experience a variety of benefits: those that are emotional in nature (e.g., wonder, pleasure, inspiration) as well as those that are more intellectually gratifying (e.g., a sense of history, an understanding of art and art history). The actual products are the exhibits themselves, with some that are permanent collections and some that are only at the museum temporarily. Augmented products and services enhance the visitor’s experiences, including lectures, concerts, tours, information centers, audio guides, benches for prolonged viewing, and even a shopping arcade and a food court.

History points to significant efforts in terms of product development: efforts to conceive and develop new exhibits such as one featuring the masterpieces from Italy that arrived with great ceremony in 1798.36 Consider product enhancements to address a mature stage in the museum’s life cycle such as the Grand Louvre Project, which spanned almost twenty years (1981–1999) and involved enlarging and modernizing the Louvre Museum and the Decorative Arts Museum.37

You can consider the museum itself the package since it is in the truest sense of the word the container for the product. This could also include the acreage and gardens where the museum is located in the heart of Paris on the banks of the Seine as well as the somewhat controversial modern glass pyramid in the central courtyard that has served as its entrance since 1989, which has proven remarkably effective in accommodating the large numbers of visitors and providing a welcoming reception; it even has become a relatively beloved landmark of the city.