Chapter 9. Influencing Positive Public Behaviors: Social Marketing

“In the 1970s, we held the world record for heart disease. The idea then was that a good life was a sedentary life. Everybody was smoking and eating a lot of fat. Finnish men used to say vegetables were for rabbits, not real men, so people simply did not eat vegetables. The staples were butter on bread, full-fat milk and fatty meat ... The biggest innovation was massive community-based intervention. We tried to change entire communities. We would go in, measure everyone’s cholesterol, then go back two months later. We didn’t tell people how to cut cholesterol; they knew that. It wasn’t education they needed; it was motivation. They needed to do it for themselves.”1

Pekka Puska Director of the National Institute of Public Health Helsinki, Finland

The Guardian, Saturday, January 15, 2005

This chapter explores a distinct marketing discipline, one that has been called Social Marketing since the early ’70s. This term is used today to specifically refer to efforts focused on influencing behaviors that will improve health, prevent injuries, protect the environment, and contribute to communities. As a fairly new discipline, challenges and questions abound for those of you charged with developing and implementing these programs:

• Social marketing theory encourages us to target people who are the most open to change. As a program administrator, I don’t get it. It’s people like the obese client I saw here at the community clinic yesterday who refuses to exercise who need the most attention.

• What do I say to citizens who say we have no business telling them they should wear a seat belt or use a condom? They ask, “What’s next? Are you soon going to start telling me I can’t smoke in my own home?”

• We don’t have the kind of funding we need to combat tobacco companies, the liquor industry, or the weed-and-feed commercials. We’re not like Pepsi competing with Coke. We’re more like David up against Goliath!

• Some of these campaigns like Click It or Ticket that people call social marketing just seem to be laws. Did the social marketer have something to do with passing the law? What? How? When?

Opening Story: From “Fat to Fit” in Finland

In January of 2005, an article by Ian Sample with the following headline and copy appeared in The Guardian: “Fat to Fit: How Finland Did It. Thirty years ago, Finland was one of the world’s unhealthiest nations ... Now it’s one of the fittest countries on earth.”2 Highlights of this country’s secrets appear in the following summary of the article, in which the government demonstrates a fundamental understanding of the depth of social marketing tools available and the breadth of their potential application.

Challenges

Holding the world’s record for heart disease evidently “shocked” the government into an aggressive effort to dramatically improve the health of the country’s citizens.

Cultural challenges in the early ’70s were pervasive, however—historic policies dictated that farmers be paid for meat and dairy on the basis of the product’s fat content; more than half of middle-aged men smoked and pubs were so popular that it seemed these men did little other than drink; and kids who were the most overweight were dropping out of sports, and those challenged to take on physical activity quickly fired back with their lack of time, the frigid temperatures, and packs of snow they faced several months in the year.

But Finland has a reputation as an innovator and didn’t let that reputation down.

Strategies

Sweeping nationwide changes were made in legislation. Tobacco advertising was banned. Farmers were provided incentives based on the amount of protein in their product rather than fat content and were encouraged to grow fruit that would naturally thrive in the climate. Policies were changed in many places, requiring citizens instead of machinery to take responsibility for clearing snow and ice from the pavement in front of their homes.

Money was shifted away from Helsinki to local authorities, making them responsible for promoting physical activity. Activities appealing to local populations were given priority, producing outcomes that led to cleaner swimming pools, more ballparks, more cycling, more Nordic walking, and well-maintained snow parks. Activities that were free or substantially subsidized were emphasized to ensure no one was excluded.

A few unusual personal interventions were tried as well. In towns where the pubs were full of middle-aged men, for example, teams would go in, speak with patrons, and engage them in conversations about what they might be interested in doing for exercise. In one region, nearly 2,000 men were either lent bikes, tempted into a swimming pool, had a shot at ball games or coaxed into cross-country skiing.3

There was a marked and deliberate cultural shift in emphasis from competitive and elite sports to health-enhancing physical activity. To encourage youth who had dropped out of sports, for example, schemes sought to dampen their competitive nature, with practices promoted for scores to go uncounted, “victories uncelebrated and winning teams unpromoted.”4

People were encouraged to incorporate exercise into their daily routines. Campaigns encouraged commuters to walk and cycle more to work. Importantly, messages were backed by changes in infrastructures, adding new walking and cycle paths, as well as money to keep them lit at night and well maintained.

Advocacy in the private sector helped overcome barriers to exercise, including one effort where the government encouraged companies to come up with non-slip shoes, addressing special concerns from seniors about falling on brisk walks. In many cities, in fact, elderly citizens could receive free sets of spikes to clamp on their shoes.

Advocacy with healthcare providers was not overlooked, with government officials encouraging physicians to prescribe levels and types of physical activity to patients, hoping it would be as common as prescriptions of medication. They called the initiative the Movement Prescription Project, counting on the finding that 80 percent of Finns consider health care professionals a reliable source of information regarding physical activity and health.5

Partnerships between public sector agencies were formed. In one Finnish town, local officials were concerned about the elderly who were staying indoors, especially during winter when it was dark and the pavements were slippery. To make it easier to exercise, authorities persuaded the transit agencies to have buses stop at senior centers and retirement homes and take them to local swimming pools, most for aqua-aerobics activities. And the swimming pools paid for the bus fare!

Rewards

Did it work?

Authorities reported that the number of men dying from cardiovascular heart disease has dropped by at least 65 percent and deaths from lung cancer by a similar margin. Physical activity has increased, and Finnish men can now expect to live seven years longer and women six years longer than before interventions were employed.

It appears that “Finland now finds itself in the spotlight from health officials across the world who are desperate to find out what it was the Finns got so right.”6

Social Marketing in the Public Sector

Social Marketing is the use of marketing principles and techniques to influence a target audience to voluntarily accept, reject, modify, or abandon a behavior for the benefit of individuals, groups, or society as a whole.7 Its intent is to improve the quality of life.

Behaviors are always the focus. It is this focus and commitment that distinguishes social marketing from education. The educator can typically “go home” when the target audience can demonstrate they have learned a new skill or retained new information. The social marketer, on the other hand, can’t quit until the person actually performs the behavior—most often, on a regular basis. It is this commitment to behavior change (for good) that also distinguishes it from social advertising. Advertising may be one of the communication strategies used to deliver messages, but it is rare that this tactic alone will move people from awareness to interest to action. You’ll need other tools in the toolbox as well, those with the familiar ring of the 4Ps.

In the area of health, social marketing efforts have been used to reduce tobacco use, increase physical activity, improve nutrition, lower the risk of stroke, prevent heart attacks, curb the spread of HIV/AIDS, help control diabetes, prevent communicable diseases, reduce use of contaminated drug syringes, prevent birth defects, reduce skin cancer, improve oral health, detect breast and colon cancers early, prevent teen pregnancies, and impact other similar health issues supported through changes in individual behaviors.

It is used for injury prevention, often targeting issues such as drinking and driving, responsible cell phone usage, drowning, domestic violence, sexual assault, fire prevention, emergency preparedness, safe gun storage, bike helmets, pedestrian safety, seatbelt usage, suicide prevention, workplace injuries, hearing loss, and proper use of car seats and booster seats.

It is critical for influencing citizens to protect the environment, with typical focuses on individual behaviors that will improve and preserve our water supply, water quality, wildlife habitats, air quality, and nonrenewable resources.

It is a discipline that can be used to enhance the community by persuading citizens to volunteer, be a mentor, stay in school, read to children, give blood, adopt a pet from the humane society, be a foster parent, vote, join a neighborhood watch program, or sign up to be an organ donor.

Who Conducts Social Marketing Efforts?

Most social marketing efforts are sponsored by public sector agencies, national ones such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Departments of Health, Departments of Social and Human Services, the Environmental Protection Agency, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, Departments of Wildlife and Fisheries, and local jurisdictions including public utilities, fire departments, schools, parks, and community health clinics. Nonprofit organizations and foundations also get involved, most often promoting behaviors that support their agency’s mission, as does the American Cancer Society when they urge people over fifty to get a colonoscopy and Nature Conservancy when they promote actions that protect wildlife habitats. And finally, you’ll see corporations engaged, as auto insurance companies urge drivers to abstain from cell phone use while driving and home and garden supply stores sponsor workshops on water conservation.

Why Is It So Hard?

For a variety of reasons, this is one of the toughest of all marketing assignments. After all, you will probably be asking people to

• Give up a pleasure (Take shorter showers.)

• Be uncomfortable (Wear a seatbelt.)

• Give up looking good (Let your lawn go brown in the summer.)

• Go out of your way (Take the bus to work.)

• Resist peer pressure (Don’t start smoking.)

• Be embarrassed (Have a colonoscopy.)

• Spend more time (Come to a health clinic to get clean needles.)

• Spend more money (Get a home emergency kit.)

• Hear bad news (Get an HIV/AIDS test.)

• Establish new habits (Walk to the grocery store.)

• Give up old habits (Don’t top off the gas tank.)

• Change a comfortable lifestyle (Turn down the thermostat.)

• Risk rejection (Take the car keys from a friend you think is drunk.)

• Learn a new skill (Compost food waste.)

• Remember something (Take your bags to the grocery store and reuse them.)

The real problem and big difference is that you don’t always have something to give, show, or promise your customer in return—especially in the near term. Try to show someone a future sustainable water supply or healthier fish as a result of their actions (sacrifices).

The remainder of this chapter shares twelve principles that social marketers have found make this tough assignment a little easier and you more successful.

Principle #1: Take Advantage of Prior and Existing Successful Campaigns

Yes, the private sector may have big budgets, but you have something they don’t. You can learn from and borrow campaigns that others in the public sector have spent time and money to develop. The marketing director for Pepsi can’t ask a counterpart at Coke how their new TV spot is working for them, and if successful, ask to use it. You can.

Begin a social marketing campaign planning process with a search for similar efforts in public sector agencies around the country, even the world. It is one of the best investments of a planner’s time. Benefits can be substantial, including learning from others’ successes and failures, having access to research conducted in preparation for the campaign, finding innovative and cost-effective strategies, and discovering ideas for creative executions and materials you might want to adapt for your campaign.

Those working in public health have a great tool to find the winners. They have access to results from CDC’s Behavior Risk Factor Surveillance System, a nationwide survey that measures and tracks more than twenty health risk behaviors among adults in the U.S. (e.g., tobacco use). A state getting ready to develop a tobacco cessation campaign, for example, can find the states with the lowest tobacco use and contact them to explore what strategies they used to achieve success. They can then test others’ materials with target audiences in their own state and make revisions that reflect any unique geographic differences.8

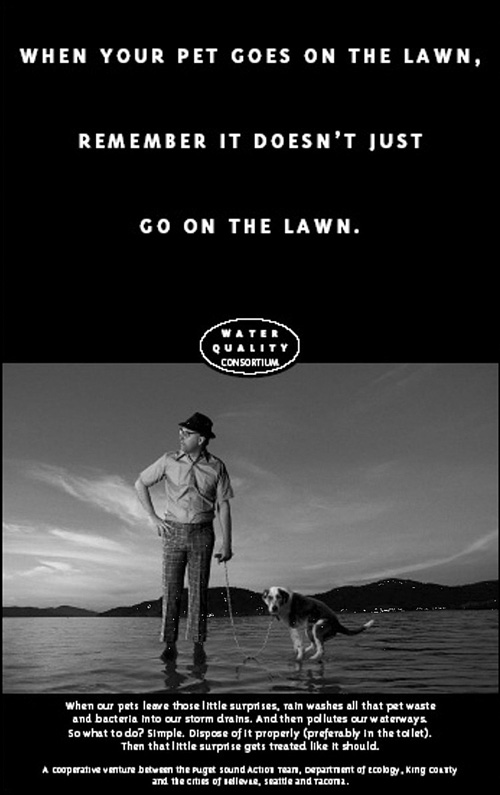

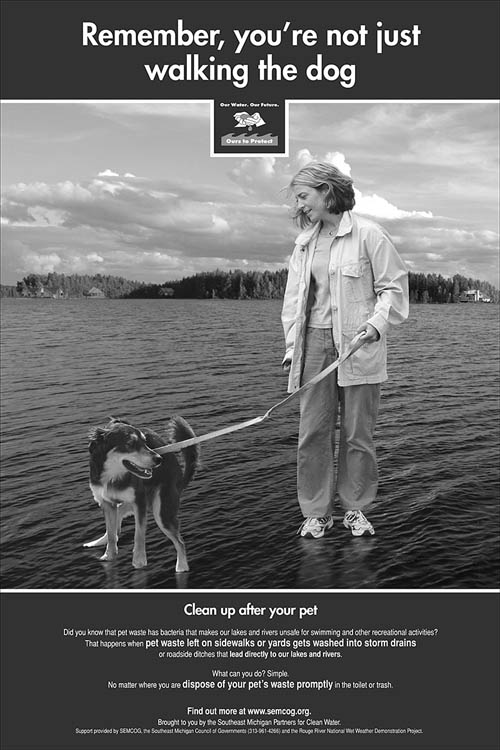

Consider the two posters in Figure 9.1, developed to improve water quality. The one on the left was developed by the Puget Sound Action Team in Washington State in 2003. The Southeast Michigan Council of Governments and the Southeast Michigan Partners for Clean Water used this creative concept to develop their own version, the one on the right, in 2004.

Figure 9.1. Michigan borrowed a creative concept from Washington State’s campaign poster on the left to influence behaviors to keep pollutants out of lakes and streams

Principle #2: Start with Target Markets Most Ready for Action

In a nutshell, the social marketer’s job is to influence some number of people to do some desired behavior, which may include abstaining from an undesirable one. It would follow, then, that efforts and resources should be directed toward those people most likely to buy (the low-hanging fruit) rather than those least likely (hardest to reach and move).

A model used frequently by social marketers to describe those most ready for action is the Stages of Change model, originally developed by Prochaska and DiClemente in the early 1980s and tested and refined by many over the past two decades.9 The original five-stage model has been collapsed by Alan Andreasen into the following four:10

• Precontemplation—Where people have no intention of changing their behavior and typically deny there is even a problem.

• Contemplation—Where people are beginning to think about a change, as something may have woken them up to the fact that they have a problem or a need to change.

• Preparation/Action—Where people have decided to do something and are beginning to put things in place in order to act. Some have actually started doing the behavior for the first time, or first several times. But it’s not a habit.

• Maintenance—Where people are performing the desired behavior on a regular basis although sometimes struggle with “relapses” and will benefit from reminders and recognition.

Although the social marketer has a role to play with each segment, you will almost always get the biggest bang for your buck (number of people adopting the desired behavior) if you target those in the Contemplation and Preparation/Action stages. Contemplators do not need to be convinced they should pick up after their pet. They just need help (e.g., a pet waste bag in the park). Those in the Preparation/Action stage have most likely overcome barriers to change. They just need reminders, reinforcement that they will realize promised benefits, and encouragement to reach desired change levels.

Now it may makes sense to you when physical activity programs target people who are exercising once or twice a week, encouraging them to increase to five, and why nutrition counselors in community health clinics might spend more time with obese clients who have been recently diagnosed with diabetes.

Principle #3: Promote Single, Simple, Doable Behaviors—One at a Time

In this world of information and advertising clutter, you often have only a few moments to speak with your audience before they hang up, leave the room, turn the page, click the mouse, or switch channels. A simple, clear, action-oriented message is the most likely to support your target market. Remember, if you are targeting those ready to change (Principle #2), you won’t have to spend as much time, money, and space convincing them they should do something. They’re just waiting for clear instructions.

Even if you have twenty-five behaviors you want them to do, it is best to present them one at a time.

Although a wide array of public activities contributes to greenhouse gas emissions, for example, one solution stands out as single, simple, and doable. The Turn It Off project in Canada was funded by Environment Canada’s Climate Change Action Plan Fund and was developed in conjunction with McKenzie-Mohr Associates and the Departments of Natural Resources and Environment. The desired behavior, to turn off your engine if you will be idling for more than 10 seconds, was directed initially to drivers dropping off and picking up their children from schools and commuters at “Kiss and Ride” lots. “Turn It Off” signs were mounted on concrete bases and placed in highly visible locations at each site. Drivers were asked to make commitments to “turn it off,” and those pledging were given window stickers that said “For Our Air: I Turn My Engine Off When Parked.” The combination of signs and commitment reduced idling by 32 percent and idling duration by an impressive 73 percent, compared to control sites (see Figure 9.2).11

Figure 9.2. A single message promoted in Canada to help reduce greenhouse gas emissions

Principle #4: Identify and Remove Barriers to Behavior Change

A list of concerns and real reasons why your target audience members perceive they can’t or don’t want to do your desired behavior should be considered a gift. Because when you have this, you are more likely to know what to say, what to do, and what to give them that will make it more likely that they will move from contemplation to preparation and from action to maintenance.

Those target audience members in contemplation, by definition, are considering this behavior, but something is typically in the way. It may be a perceived lack of skill (keeping a worm bin alive for composting), a concern with self-efficacy (ability to quit smoking), or a real inconvenience (taking the motor oil to a transfer station). For those already in action, the reason they might not be doing something on a regular basis could be that they simply forget (to floss each night), or it might be something more significant, like they think the desired level of the behavior is “over the top” (eating five to nine fruits and vegetables a day) or even “ridiculous” (following the vet’s recommendation to brush your cat’s teeth every day).

Identifying these barriers can actually be as simple as asking your target audience (in groups or individually): What are some of the reasons you haven’t done this in the past? What do you prefer to do instead? What might get in the way of doing this in the future?

A counselor in a community clinic working to influence clients to have family meals together as a way to ensure better nutrition and stronger families might get an earful: We have different schedules. We don’t like to eat the same things. I don’t really know how to cook. It’s more expensive. We wouldn’t know what to talk about. I work all day, come home, and then find I don’t have anything in the cupboard, so we just go get fast food.

On the other hand, a city utility wanting citizens to take a five-minute shower might only hear one big reason, one they could respond to pretty quickly (see Figure 9.3).

Figure 9.3. This hourglass fixture can be attached in the shower as a response to citizens wanting to help conserve water but not knowing when the desired five-minute shower is up.

Principle #5: Bring Real Benefits into the Present

Benefits are something your target audience wants or needs that the behavior you are promoting can provide. Though simple in theory, the practice is not easy. Two strategies will assist you.

The first is to understand the real benefits that are being sought. Bill Smith at the Academy for Educational Development in Washington, DC asserts that these benefits may not always be so obvious and that defining them is one of the greatest challenges of consumer research. For example, “The whole world uses health as a benefit. [And yet] health, as we think of it in public health, isn’t as important to consumers—even high end consumers—as they claim that it is. What people care about is looking good (tight abdominals and buns). Health is often a synonym for sexy, young, and hot. That’s why gym advertising increases before bathing suit time. There is not more disease when the weather heats up, just more personal exposure.”12

Your next assist is to focus on near-term benefits, those that will be realized as soon after the behavior as possible. Michael Rothschild at the University of Wisconsin asserts that this is because rewards are “worth less in the future” and at the same time “costs are less onerous in the future.”13 He speaks of “the tyranny of small decisions,” where “people tend to choose what is best for them in the short-run, and ignore the long-run implications.”14 To succeed, he advises that marketers should bring future value closer to the present.

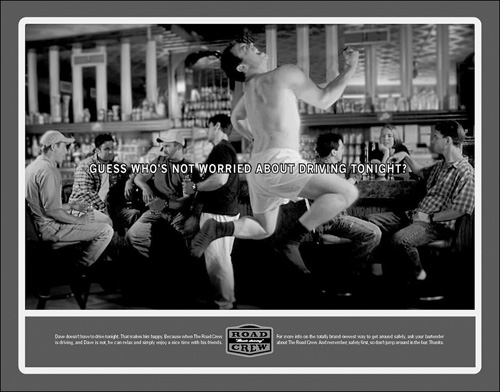

This principle was exemplified in a project in Wisconsin sponsored by the Wisconsin Department of Transportation/Bureau of Transportation Safety and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, for which Rothschild was the principal investigator. The program’s objective was to reduce drunk driving among 21- to 34-year-old single men living in rural areas who were driving home after a night of drinking in bars and taverns. The key insight came when they told program planners that if the planners wanted to give them a ride home, they would also need to give them a ride to the bar. The service, branded “Road Crew,” provides rides from homes to bars and back home again and is loaded with immediate benefits—looking cool being picked up by a limo and having fun riding with others between bars. At the same time, many costs were eliminated, reducing the negative image associated with leaving your car at the bar overnight or the worry many felt when driving home intoxicated.

The campaign’s slogan “Road Crew, Beats Driving” and advertising highlighted these immediate no hassle, fun, and cool benefits (see Figure 9.4).

Early results indicated the program was persuasive, with almost 20,000 rides given to potential drunk drivers between July 1, 2002 and June 30, 2003. These rides were estimated to have prevented 15 alcohol-related crashes on area roads, a 17 percent reduction. Further calculations indicated the program also provided a good return on investment, with costs to avoid a crash estimated at $15,300 compared with the average cost of an alcohol-related crash in Wisconsin of approximately $56,000.15 Since mid-2003, the programs have continued as self-sufficient operations, not using any government funds. (For more information and a short video, go to www.roadcrewonline.org.)

Figure 9.4. Near-term benefits of letting the Road Crew do the driving were highlighted in this successful effort to reduce drinking and driving in rural Wisconsin.

Principle #6: Highlight Costs of Competing Behaviors

Now you switch to the other side of the exchange equation where you focus on identifying the competition for your behavior and the costs your target market may (or may not yet) associate with them.

The competition in social marketing is the behavior your target audience prefers, might be tempted to do, or is currently doing—instead of the one you would like them to do. And the competition can be tough. For physical activity, it may be working through a lunch hour; for flossing teeth, it might be watching television; for putting a child in a car seat, it may be holding them in your lap; for using natural fertilizers, it may be a greener, weed-free lawn; for giving blood, it may be going straight home from work to spend time with your family.

After the competition is identified, the next question to explore is what costs your target market associates with “buying” the competing behavior rather than yours. These may be direct costs associated with the behavior (e.g., cancer from smoking), or they might be the loss of benefits they would otherwise enjoy if they performed your behavior (e.g., weight loss from physical activity).

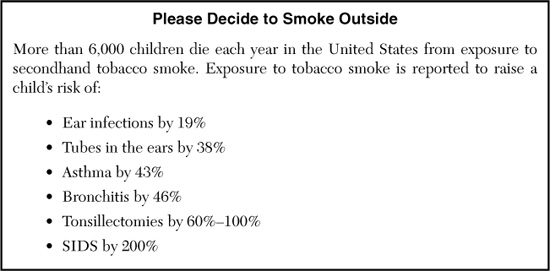

This sixth principle urges you to explore and then highlight important costs the target audience believes they will have to pay if they favor the competition. Consider, for example, the costs listed in Figure 9.5 that Snohomish Health District in Washington State highlighted when parents smoke around their children in their homes or cars.

Figure 9.5. Key messages used in Snohomish County, Washington to encourage parents to smoke outside instead of in the home or in their cars

These specific costs were chosen when parents indicated they knew it might be harmful but were “shocked” at the actual statistics that had been verified by medical associations. A follow-up survey with 500 households six months into the campaign found that among those who saw the campaign, 21 percent who had allowed smoking in their car changed their rules and 17 percent who used to allow smoking in their home changed their habits.16

Principle #7: Promote a Tangible Object or Service to Help Target Audiences Perform the Behavior

Although tangible objects and services may be considered an optional component of a social marketing effort, they are sometimes exactly what is needed to help the target audience perform the behavior, provide encouragement, remove barriers, or sustain behavior. They provide opportunities to brand and make the campaign more concrete, creating more attention, appeal, and memorability. Examples are varied, with some offered directly by a public agency and others only promoted by the agency as a part of a campaign:

• Helpline for domestic abuse

• Laminated instruction card for breast self exam for placement on shower nozzle, even providing a water-soluble pen to note when completed

• Colored chopping blocks to increase safe food handling: yellow for poultry, red for meat, and green for vegetables

• University escort at night if you don’t have someone to walk with back to the dorm after class

• Disposable cigarette butt pouches

• Stylish walking sticks (rather than a cane) to help prevent senior falls

• A magnifying glass attached to pesticide containers to help read the instruction and warning labels

The City of Johannesburg (Joburg) in South Africa featured a news article covering the services of a local company on their official Web site, a company they evidently believe will help reduce injuries and deaths from drinking and driving—at no cost to taxpayers. “You are a driver, you like drinking and you usually drink and end up driving under the influence. You know one day—rather—one night—you will be nabbed? Relax. Now you can guzzle like a fish, jump into your car and get home safely without the police bothering to plunge the dreaded breathalyzer into your mouth. That’s because you’re not in the driver’s seat, but sitting next to a chauffeur from Toot-n-Scoot, a rare Johannesburg company that dispatches drivers on scooters to take people home once they are sizzled.” The novelty of the concept is that the driver arrives at the client’s car on a scooter, which is then collapsed and put in the “boot of your car.” After dropping you off at your house, the driver removes the scooter and heads off to the next call. This Toot-n-Scoot service was first offered in 2003, and charges for the service range from R50–R150 (R=Rand), depending on the distance (about $10–$30 U.S.).17

Principle #8: Consider Nonmonetary Incentives in the Form of Recognition and Appreciation

The principle here is to consider what you can give to your target audience in recognition and appreciation for their behavior change—acknowledging the extra time they spent (e.g., sorting office paper), the habits they broke (e.g., topping off a gas tank), the pleasures they gave up (e.g., taking a shorter shower), the discomfort they experienced (e.g., wearing a life vest), the risks they took (e.g., suggesting that a neighbor use only natural fertilizers), the extra money they spent (e.g., buying an emergency kit), or the embarrassment they felt in the process (e.g., asking for an HIV/AIDS test).

In this case, we are referring to “gifts” that your agency or one of your partners gives, often unexpected and having some psychological value to your customer:

• A yard plaque saying “Backyard Wildlife Sanctuary” mailed to a homeowner for pledging to follow natural yard care practices

• A lapel pin for employees who use alternative transportation to commute to work

• A certificate presented to attendees completing a CPR class offered at the fire station

• A thank you call to a parent from a school principal expressing appreciation for volunteer work

• A bracelet for the designated driver, also signaling that they get a free non-alcoholic drink at restaurants and bars working in partnership with governmental agencies

• An award presented at a city council meeting to a local business for its increased recycling efforts

• A “high five” given by lifeguards at a public beach to kids wearing a life vest

• A window sticker for businesses who adopt environmentally friendly practices

• A letter from a director of a community health clinic congratulating a client for being smoke-free for thirty days

• An article in a business journal recognizing corporations who have supported a local beach cleanup effort

This tactic has several advantages. It is typically less expensive than offering monetary incentives such as discounted or free products and services (e.g., coupons for a child’s life vest). It can be quite effective in influencing the target audience to sustain the desired behavior into the future because it has the potential to function well as a prompt or reminder (e.g., the Backyard Wildlife Sanctuary sign reminding the homeowner that he or she committed to keeping the bird bath clean). And perhaps most powerfully, it can make the desired behavior more visible and appealing to others, even creating the perception of a social norm for the behavior (e.g., the lapel pin indicating that the employee is doing his or her part for air quality and traffic congestion).

Principle #9: Have a Little Fun with Messages

Using humor to influence public behaviors can be tricky, especially for the government. There are times when it isn’t appropriate for the target audience (e.g., victims of domestic violence). There are agencies with a brand personality where humor doesn’t quite fit (e.g., the military in a time of war). There are some messages that are so complex they could be lost or overridden by a humorous approach (e.g., how to baby-proof your home). And there are certain behaviors that are more likely to be inspired by some other emotion (e.g., when getting people to evacuate before an impending hurricane).

You are encouraged, however, to look for opportunities where it might be appropriate for the audience, where it wouldn’t be inconsistent with your brand, and where it may be just the right emotion to garner the attention, appeal, and memorability you want in your campaign.

Pet waste is a subject that most people would probably like to avoid. But many communities have a little fun with it, as they do in Austin, Texas. The city’s Watershed Protection Department makes Mutt Mitts available in Scoop the Poop boxes in city parks (see Figure 9.6). They believe citizens are responding to their plea. Based on the number of mitts distributed in one year alone, they estimate that they removed 135,000 pounds of waste and its related bacteria from watersheds.18

Figure 9.6. Having a little fun in Texas with messages to pet owners (http://www.ci.austin.tx.us/watershed/downloads/scoopsign.pdf)

Principle #10: Use Media Channels at the Point of Decision Making

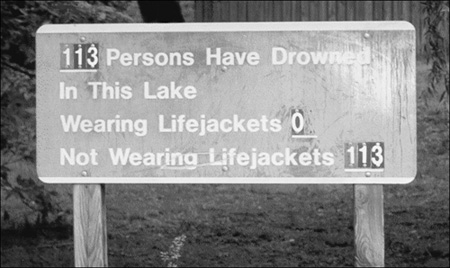

Many social marketers have found that an ideal moment to speak to your target audience is when they are about to choose between alternative, often competing behaviors.19 They are at a fork in the road, with your desired behavior in one direction and their current behavior, or potential undesirable behavior, in the other. The social marketer wants a last chance to influence this choice, and being at the point of decision making with your messages can be powerful (see Figure 9.7).

Consider the impact of the placement of these “just-in-time” messages:

• The use of the © symbol on menus signifying a smart choice for those interested in options that are low in fat, cholesterol, and/or calories

• The idea of encouraging a parent who smokes and wants to quit to put their child’s photo inside the wrapper of their cigarette pack

• A stencil on a storm drain reminding citizens that what they are about to put down the drain (e.g., motor oil) will go directly to lakes, rivers, and streams

Figure 9.7. A just-in-time message at a boat ramp on a lake to increase the chances that someone will decide to bring a lifejacket along

Principle #11: Get Commitments and Pledges

A commitment or pledge to perform a behavior has been shown to significantly increase the likelihood that your target market will actually follow through.

Behavior psychologist Doug McKenzie-Mohr considers commitments and pledges one of the major tools you can use to influence behavior change, one that can produce dramatic results. He emphasizes the importance, though, of starting with small initial requests because research has proven that those who agree to a small step are more likely to agree to a subsequent larger one. For example, a sampling of registered voters were approached one day prior to a U.S. presidential election and were asked, “Do you expect you will vote or not?” All agreed that they would vote. Relative to voters who were not asked this simple question, their likelihood of voting increased by 41 percent.20

He offers several tips to leverage the effectiveness of this tool: emphasize written over verbal commitments (e.g., signing a pledge to use alternate transportation once a week), ask for public commitments (e.g., having names advertised in a newspaper), seek commitments in groups (e.g., signing as a member of a church congregation), use existing points of contact to obtain commitments (e.g., when people purchase paint, ask them to sign a commitment that they will dispose of any leftover paint properly), don’t use coercion and instead seek commitments when people appear already interested in an activity (e.g., those attending a natural yard care workshop), and use the most durable forms and formats to display commitments (e.g., a sticker on recycling containers rather than a listing of names in a newsletter).21

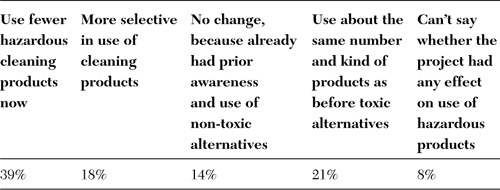

In Portland, Oregon, this commitment tool and small steps principle was used successfully to reduce the usage of hazardous household products among families with preschool-age children. Metro’s Household Hazardous Waste program partnered with three childcare facilities to pilot and evaluate a program targeting parents. The project included seven weeks of onsite educational displays and materials as well as three commitment actions for facility staff and adult family members: a pre-project survey measuring participants’ current knowledge and use of hazardous household products, a pledge to use an alternative household cleaner (see Figure 9.8), and a post-project survey to evaluate use of hazardous household cleaners after participating in the project. Results reflected in Table 9.1 were encouraging, indicating that the commitment strategy changed the behaviors of about half of study participants.

Figure 9.8. Pledge form used in Portland, Oregon with parents of children in a childcare facility

Table 9.1. Survey results among participants in a pilot project in Oregon using commitments to reduce use of hazardous household cleaning products

Principle #12: Use Prompts for Sustainability

A prompt in a social marketing environment serves an important purpose—a reminder. McKenzie-Mohr and Smith in their book Fostering Sustainable Behavior caution that this tactic is not likely to change attitudes or increase motivation; rather, it will simply remind your target audience to engage in a behavior they have already decided they want to do. In these cases, the primary barrier is “the most human of traits—forgetting.”22

Prompts are typically visual or auditory in nature, can be used for a variety of behaviors, and can take one of many forms: a label on a public bathroom towel dispenser suggesting to “Take only what you need,” a sign at a gas station reminding a customer to check their tire pressure, Post-it Notes left by cleaning staff at a university reminding faculty to turn off their computer monitors when leaving at night, a grocery store clerk asking a customer in the checkout lane if they brought their own bag, a refrigerator magnet reminding homeowners what week they should put out their food waste containers, tent cards on tables at restaurants explaining that you won’t automatically be served water, messages on fast-food bags reminding patrons to dispose of litter properly, posters in bar restroom stalls graphically depicting someone bending over “the porcelain god” serving as a reminder to drink moderately, a sticker for a calendar indicating it’s time to check the smoke alarm batteries, an email alert from a utility signaling the homeowner it’s time to turn the compost bin, and a letter from the state health department encouraging a parent of a toddler to check whether their immunizations are up to date.

To be effective, McKenzie-Mohr and Smith suggest that the messages should be self-explanatory (e.g., turn off the light) and located as close in time and space as possible to the targeted behavior (e.g., placing the prompt to turn off the light directly on a light switch).

You might also want to try creative tactics to engage and interact with citizens, as they certainly did in the Netherlands at a theme park where tales of Danish Hans Christian Andersen are featured. One sculpture of a whimsical character is connected with an infrared sensor so that every time a person passes by, it is activated and says, “Got litter?” Kids are especially fond of feeding this guy, and the nice effect is that kids often actively search the area for stuff to feed it. After all, every time the kids throw in something, he says “Thank you!” Another similar approach is used in Washington State with a litter receptacle fondly referred to as the Garbage Goat (see Figure 9.9).

Figure 9.9. This vacuum powered Garbage Goat at Riverfront Park in Spokane, Washington, “eats” anything that comes close to his mouth. (Photo courtesy of Gary Nance, Spokane, WA)

Applications Upstream

Up to this point in the chapter, discussions have focused on influencing individual behaviors. In a metaphoric sense, the strategic focus for addressing social issues has been downstream—on individuals who have a problem (e.g., high blood pressure), who are contributing to the problem (e.g., taking computers to the dump), or who are not part of the solution (e.g., giving blood). Many believe we have been placing too much of the burden for solving these social issues on individual behavior change and missing opportunities to alter infrastructures and other environmental factors, even legal actions, that make change easier and more likely—opportunities that are upstream.

Alan Andreasen in his book Social Marketing in the 21st Century describes this expanded role for social marketing well: “Social marketing is about making the world a better place for everyone—not just for investors or foundation executives. And, as I argue throughout this book, the same basic principles that can induce a 12-year-old in Bangkok or Leningrad to get a Big Mac and a caregiver in Indonesia to start using oral rehydration solutions for diarrhea can also be used to influence politicians, media figures, community activists, law officers and judges, foundation officials, and other individuals whose actions are needed to bring about widespread, long-lasting positive social change.”23

Consider the issue of the spread of HIV/AIDS. Downstream, you focus on decreasing risky behaviors (e.g., unprotected sex) and increasing timely testing (e.g., during pregnancy). Now, in your mind’s eye, move upstream and notice groups and organizations and corporations and community leaders and policy makers that could make this change a little easier or a little more likely, ones that you then choose as your target market for a social marketing effort. You could encourage pharmaceutical companies to make testing for HIV/AIDS quicker and more accessible. You could work with physicians to create protocols to ask patients whether they have had unprotected sex and if so encourage them to get an HIV/AIDS test. You could advocate with offices of public instruction to include curriculums on HIV/AIDS in middle schools. You could support needle exchange programs. You could provide the media with trends and personal stories. You might look for a corporate partner that would be interested in setting up testing at their retail location. You could organize meetings with community leaders such as ministers and directors of nonprofit organizations, even provide grants for them to allocate staff resources to community interventions. If you could, you would visit hair salons and barbershops, engaging owners and staff in spreading the word with their clients. You might testify before a senate committee to advocate for increased funding for research, condom availability, or free testing facilities.

The process you follow and principles that guide you will be the same ones you used for influencing individuals. You have “simply” changed your target market.

Summary

Social marketing principles and techniques are most appropriate when the purpose of your marketing efforts is to influence behaviors intended to improve health, prevent injuries, protect the environment, or contribute to communities. Behaviors are always the focus. Some describe this discipline as the toughest of all marketing assignments because you will be asking target audiences to do something for which you are not always able to give them or show them something in return, especially in the near term.

Twelve principles will help make this task easier and you more successful:

#1: Take Advantage of Prior and Existing Successful Campaigns

#2: Target Markets Most Ready for Action

#3: Promote Single, Simple, Doable Behaviors—One at a Time

#4: Identify and Remove Barriers to Behavior Change

#5: Bring Real Benefits into the Present

#6: Highlight Costs of Competing Behaviors

#7: Promote a Tangible Object or Service to Help Target Audiences Perform the Behavior

#8: Consider Nonmonetary Incentives in the Form of Recognition or Appreciation

#9: Have a Little Fun with Messages

#10: Use Media Channels at the Point of Decision Making

#11: Get Commitments and Pledges

#12: Use Prompts for Sustainability

Although most social marketing campaigns to date have focused primarily on influencing individual behaviors, experts are now urging you to move your target market lens upstream, zooming in on organizations, groups, corporations, policy makers, law makers, and others who have an impact on infrastructures and who can make it a little easier, cheaper, convenient, and even fun and popular for individuals to “behave.”