Chapter 6. Creating and Maintaining a Desired Brand Identity

“Energy efficiency has finally come of age. Today, with energy prices at an all-time high, and the era of cheap energy most likely over, consumers and businesses are increasingly investing in energy efficiency for a variety of benefits: to save energy, save money, help the environment, provide a better future for their families, and reflect commitment to social responsibility. ENERGY STAR® has succeeded as a brand because of our common sense approach to promoting better, more efficient technologies and practices, and because we’ve been able to translate the value of these practices to consumers and industry. Building awareness and demand did not happen overnight. It took patient, steady work with our industry partners, careful program design, and a brand communications strategy that has evolved with the times.”

Jill Abelson Communications Manager ENERGY STAR®

The following question isn’t a test. It’s an exercise. Be sure to take your time. When you read each of the following names, write down the words, images, and feelings that come to your mind ... first.

• IRS

• The National Archives

• Department of Labor and Industry

• The U.S. Presidential Elections

• Smokey Bear

• Singapore

• Canada

• Las Vegas

• Paris

• Harlem

• Your City’s Police Department

• Your City’s Library

• Your District’s School Superintendent

Now, a second question. Who is responsible for what came to your mind, for whether you had rich positive associations or vague, even negative ones? If you interpret the word “responsible” to mean “able to respond,” it suggests that managers and directors of these agencies, program, cities, and nations can and should be the ones looked to—for maintaining a strong brand, strengthening a weak one, or changing an undesirable one. In this opening story on creating and maintaining a desired brand image for a governmental program, the role that marketing plays to fulfill this responsibility will become clearer.

Opening Story: ENERGY STAR®—A Brand Positioned to Help Protect the Planet

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) established the voluntary ENERGY STAR program in 1992, and it has partnered with the Department of Energy (DOE) since 1996 to increase the nationwide use of energy-efficient products and practices. Computers and monitors were the first labeled products, integrating the power-saving features initially used in laptop technology. Today, the program encompasses more than 40 product categories for the home and workplace, as well as complementary programs for new homes, existing homes, and commercial and industrial buildings. This story focuses on ENERGY STAR’s efforts in the residential market. A strong brand strategy played a key part in building one of the most successful government-industry partnerships.

Challenges

At the early stages, before consumer demand could be created for ENERGY STAR, EPA needed to encourage the marketplace to manufacture more energy-efficient products and to use the label. Manufacturers that met the voluntary specifications were encouraged to label the qualified products with the ENERGY STAR logo. After the label for computers was established, EPA used this success to work with other manufacturers to expand the program to a wider array of labeled products, moving first to other types of office equipment and then to heating and cooling equipment, appliances, light fixtures, new homes, and electronics.

The next challenge facing ENERGY STAR was how to get consumers interested in purchasing energy-efficient products. Research showed that consumers had little knowledge about the energy use of products—and almost no awareness that the energy they used at home contributed to air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. Using this research as a foundation for brand education and messaging, EPA set off on a brand communications campaign, this time directed at consumers.

Strategies

Planning began in 1996 with identifying the primary target audience as environmentally concerned consumers who wanted to save money on utility bills. The target consisted of college-educated consumers ages 25 to 54 with above-average incomes who were living in regions with high energy costs (due to extreme heating or cooling seasons).

Key messages addressed the insight that most people didn’t understand the link between home energy use and air pollution. Given the fact that the target audience wanted to do things to help protect the environment, the brand promise was born:

“By purchasing ENERGY STAR products you can save money and help protect the environment at the same time.”

The brand personality was intended as “smart, credible, easy, important, and approachable.” Building brand credibility was also a key aspect of the launch. For consumers to trust the ENERGY STAR label, they needed to know that it was coming from a reliable source—the U.S. EPA.

The launch of the brand focused on media tours in each market where spokespeople delivered “did you know” factoids (Did you know your house pollutes more than your car?) with local consumers offering testimonials about cost savings with ENERGY STAR labeled products. EPA developed television and print public service announcements (PSAs) to help maximize message impact. Local utilities, retailers, and manufacturers helped promote the program through education, rebates, and in-store promotion. Other private companies carried brand messaging, including in-store video at Blockbuster, cups and bags at McDonald’s, and online messages through Yahoo! In eighteen months, national recognition of the ENERGY STAR label grew from zero to 27 percent.

Over the years, EPA continued umbrella brand communications through new PSA campaigns, media relations activities, educational materials, national retail promotions, and a consumer Web site (www.energystar.gov) and toll-free hotline (see Figure 6.1).

Figure 6.1. Print PSA for ENERGY STAR

National product promotions, such as the Change a Light, Change the World campaign helped build and support the ENERGY STAR brand. The Change a Light campaign pairs up EPA/DOE, utility partners, and national retailers in a unified educational effort about efficient lighting. This promotion uses a social marketing model to encourage consumers to make a pledge to do their part while also offering consumers a low-risk way to try the ENERGY STAR brand (see Figure 6.2).

Figure 6.2. A campaign pairing up the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency with the Department of Energy

The future brand strategy will evolve by continuing to increase brand awareness while also increasing the depth of understanding of both the environmental benefits of the brand and breadth of ENERGY STAR product and service offerings. In addition, the brand will focus on strategies to engage the loyal consumers of ENERGY STAR to help advocate for the brand to their friends and families.

Rewards

ENERGY STAR achievements to date include the following:

• The ENERGY STAR label is now recognized by more than 64 percent of the American public—awareness is higher in areas with active utility partners.

• 30 percent of U.S. households report knowingly purchasing an ENERGY STAR qualified product in the past year.

• Consumers have purchased more than 1.5 billion ENERGY STAR qualified products.

• There are more than 1,400 manufacturing partners in 40 ENERGY STAR product categories representing 32,000 models.

• The program has more than 800 retail partners representing 21,000 storefronts.

• Many local builders are constructing 20 percent or more of their new homes to meet ENERGY STAR criteria.

• There are more than 2,000 ENERGY STAR labeled commercial buildings.

• In 2004 alone, Americans with the help of ENERGY STAR saved enough energy to power 24 million homes and avoid greenhouse gas emissions equivalent to those from 20 million cars—all while saving $10 billion.

Branding in the Public Sector

Brand and branding conversations are familiar, even old, in the private sector. They got really fired up in the ’70s by articles on positioning, especially those of Al Ries and Jack Trout who ignited the advertising world with bold contentions that positioning starts with a product, but it isn’t what you do to a product. “Positioning is what you do to the mind of the prospect. That is, you position the product in the mind of the prospect.”1 We would add, “where you want it to be.”

Branding is one strategy you and your agency can use to secure a desired position in the prospect’s mind. (Decisions you will make regarding the first 3Ps and how they are eventually executed contribute to this positioning as well.) The process begins with decisions regarding a desired brand identity (how you want to be seen) and is then managed to ensure that your brand image (how you are actually seen) is on target.

No doubt you have been witness to conversations in the public sector where a colleague mentioned something related to branding, started by a comment like “We need a better brand image.” Some responded with big smiles on their faces, eager to carry the conversation forward and glad someone brought it up. There were also, no doubt, those in the room who responded with a skeptical eyebrow, probably thinking to themselves, “Here we go again. Playing like we’re a big business. Branditis strikes again!”2 And then there were a few souls with blank stares and the courageous among them who proclaimed, “I thought branding was something we did for cattle.”

To help develop your response to conversations such as these in the future, this chapter begins with definitions, associated branding terminology, and a description of elements typically included in decisions regarding brand identity.

Branding Defined

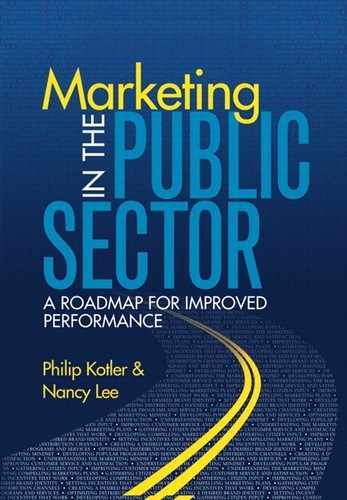

Branding terminology is bantered around a lot among academics, as well as advertising and marketing professionals. Although labels are not as important as the distinctions themselves, it helps to have some familiarity with them. The presentation in Figure 6.3 is intended as a quick reference, providing you with a listing of terms used most frequently and a concise, albeit simple, description of each.

Brand Elements

Elements of the brand are those devices that serve to identify and differentiate the brand. Most are trademarkable and include the name and any slogan, logo (graphic elements), characters, music, signage, packaging, even colors used consistently. When they’re really good, as portrayed in the following example, you’ll want to control their use by others and leverage their perceived value as they become vital to your success.

The guardian of forests in the U.S., and one of the world’s most recognizable fictional characters, has been a part of the American scene for more than sixty years. Smokey Bear, dressed in a ranger’s hat and belted blue jeans and carrying a shovel, has been the recognized wildfire prevention symbol since 1944 (see Figure 6.4). The slogan “Only YOU Can Prevent Forest Fires” was first used in 1947 and was only changed slightly in 2001 when his message was updated to “Only YOU Can Prevent Wildfires” to address the increasing number of wildfires in the nation’s wildlands (see Figure 6.5).

By 1952, the Smokey Bear symbol began to attract commercial interest, enough so that legislation was passed to take Smokey out of public domain and place him under the control of the Secretary of Agriculture. An amendment in 1973 offered commercial licensing and directed that fees and royalties were to be used to promote forest fire prevention. Hundreds of items have been licensed under this authority over the years, several featured in Smokey’s “Museum” on his official Web site SmokeyBear.com.

In 1984, Smokey’s 40th birthday was commemorated, and Smokey became the first individual animal ever to be honored on a postage stamp. In 1987, Smokey Sports was launched with a “National Smokey Bear Day” conducted with all major league baseball teams in the United States and Canada. The decade of the ’90s opened the door for Smokey’s revitalization and revival by celebrating his 50th birthday nationwide with high visibility activities and events, and in 2004, he celebrated yet another milestone with a “Sixty Years of Vigilance” theme.

Has all this effort to prevent wildfires had an effect? Well, according to the USDA Forest Service, in 1941 over 30 million acres of wildlands were burned by carelessness; in the 1990s, less than 1 million acres were burned.11

Figure 6.4. Poster used in 1948

Figure 6.5. Image and slogan used in 2005

Brand Function

By definition, the primary practical function of a brand is to identify the maker or seller of a product, with product interpreted broadly here to include tangible goods, services, organizations, people, places, and ideas. Of most interest is what good this can do ... for you as well as your key publics.

For your agency and its programs, a strong brand image can serve you well in helping meet several marketing objectives. Heightened awareness and understanding of the features, spirit, and personality of your brand may make all the difference in usages levels (e.g., seeing your city as a great travel destination spot). A recognizable and trusted brand image may make it more likely that a citizen will participate in one of your programs (e.g., joining a Neighborhood Watch group). It might even persuade someone to comply with guidelines and laws (e.g., properly disposing of litter).

In the spirit of a win-win situation, strong brands meet the needs of citizens as well, assisting them in finding what they are looking for, helping them make their decisions quickly and with confidence. It may even satisfy a less tangible need as a form of self-expression. The following example brings this to life.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture has established a set of national standards that food labeled “organic” must meet, whether it is grown in the United States or imported from other countries. Consumers interested in purchasing organic produce, meat, eggs, dairy products, and foods made with organic ingredients can look for the official USDA organic seal, often signified with a sticker on vegetables and fruit, organic produce displays, or on packaging labels, as illustrated in Figure 6.6.

Figure 6.6. Sample cereal boxes illustrating four labeling categories. From the left: cereal with 100 percent organic ingredients, cereal with 95 to 100 percent organic ingredients, and cereal with 70 to 95 percent organic ingredients. Makers of the cereal with less than 70 percent organic ingredients may list specific organically produced ingredients on the information panel of the box but may not make organic claims on the front of the box12

Creating a Desired Brand Identity

Six steps are proposed to create a strong brand image, with simple questions that will assist you in completing each step. The first five steps are illustrated with an example to increase physical activity among youth. To provide a range of branding examples, the sixth step is described with a different example, one with an intention to decrease littering.

Step 1: Establish Brand Purpose

What marketing objectives do you want the brand to support? As noted earlier, most commonly these will be objectives related to influencing citizens to support your organization, participate in your programs, utilize your services, and/or comply with guidelines and laws.

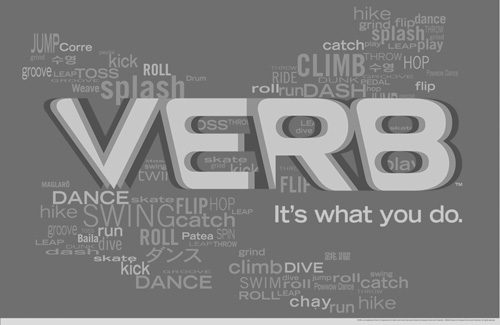

“VERB™ It’s what you do” is a national, multicultural social marketing campaign coordinated by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) with a purpose to influence young people ages 9 to 13 (tweens) to be physically active every day.13

Step 2: Identify Target Audiences for the Brand

Who are primary target audiences that will be exposed to the brand that you want to influence? Although in reality many citizens in the general public will be exposed to your brand, it should be designed with specific groups of people in mind, those you want to be most influenced.

Although the primary target audience for the VERB effort is tweens, additional important audiences include other school-aged kids—who no doubt will be exposed to the campaign—parents, and adult influencers (e.g., teachers, youth leaders, physical education and health professionals, pediatricians, health care providers, and coaches).

Step 3: Articulate Your Desired Brand Identity

What do you want target audiences to think and feel when they are exposed to your brand? In the beginning of the chapter, you were encouraged to note the images, words, and feelings that came to your mind for a variety of agencies, cities, and nations. This is your chance to envision how you hope target audiences will respond. This step can be as simple as filling in the blanks to the following sentence: “I want my target audience to see (MY BRAND) as ____________________.”

Based on formative research and pretesting, VERB’s program planners determined they want tweens to see regular physical activity as something that is cool and fun. Words like “exercise” rarely appear in campaign materials, with references to activities, games, play, and sports more the norm.

Step 4: Craft the Brand Promise

What benefits for the target audience will you highlight? The trick in this step is to focus on benefits for your target audience, not your agency, ones the target audience is likely to experience if they engage in the desired behavior.

Tweens are promised that they will receive what formative research indicated they wanted—that by choosing and engaging their VERB, fun will follow, including in many cases great prizes and great deals (see Figure 6.7). Primary benefits articulated for parents and adult influencers emphasize that increased physical activity will help reduce childhood obesity, citing that children today spend less time being physically active and more time doing sedentary activities. As a result, there has been an increase in the number of overweight youth in the United States, and research shows that being overweight can increase one’s risk for type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, sleep apnea, and gall bladder disease.

Figure 6.7. Campaign material used in Lexington, Kentucky highlighting the brand promise

Step 5: Determine the Brand’s Position Relative to the Competition

What makes your brand a good choice, one better than the competition? Challenge yourself here to first identify the competition, direct as well as indirect. In the public sector, this often relates more to alternatives that citizens have to programs and services that you offer (e.g., UPS for the Postal Service and french fries for the “5 A Day” campaign that promotes fruits and vegetables). Then dig deep for your brand’s unique points of difference. What do you offer that the competition doesn’t? What can you do better?

VERB clearly distinguishes itself from a generic exercise brand. As the slogan “It’s What You Do” implies, tweens have different interests and skill levels, and there are many verbs that can get them into action. Tweens are encouraged to use their imagination. Materials suggest they can decide to walk, leap, run, dive, play, twist, bounce, tumble, spin, swing, tag, jog, flip, dash, catch, dance, run, swim, hop, kick, dribble, climb, skate, bowl, bike, stretch, or pitch ... or any combination of these. You decide (see Figure 6.8).

Figure 6.8. Tweens are encouraged to “pick their verb”

Step 6: Select Brand Elements

What name, slogan, logo, and colors will be associated with the brand? Will there be any consistent use of characters, music, signage, or packaging that will be a core element of the brand? In choosing brand elements, a judicious approach will be most rewarding, one that will support decisions you have already made regarding brand purpose, target audience, brand identity, brand promise, and brand positioning. Kotler and Keller have identified six major factors to guide these selections, ones that can be used to evaluate a pool of options, testing them with target audiences relative to these ideals:14

Memorable—How easily will this brand element be recalled and recognized? Short and catchy names and phrases such as Click It or Ticket and AMBER Alert can help, as can symbols such as ones used for recycling (see Figure 6.9).

Meaningful—Ideally, the brand element suggests something informative and relevant to the target audience, something that helps them decide whether to “participate.” Consider the inherent and rich meaning in names such as “Neighborhood Watch” and “Parents: The Anti-Drug.”

Likeable—How aesthetically appealing are the proposed brand elements, both visually as well as verbally? Is it something citizens might even want to put on their clothing, cars, or perhaps in their homes, images such as ones of the Great Wall of China or the Eiffel Tower? Or how about your state’s litter prevention slogan?

Transferable—Will you be able to use the brand element under consideration to introduce new products in the same or different categories? A different version of the recycle symbol, for example has been used for glass and corrugated packaging. (See Figure 6.10.)

Figure 6.10. Extending the recycle symbol to specific materials

Adaptable—Consider how adaptable and updatable the brand element will be in the future. This is especially true when using characters as a core element of the brand, ones like Smokey Bear.

Protectable—Will you be able to legally protect the brand element, or is it so generic that “anyone” could use it? Can it be too easily copied or used inappropriately? Although it might at first seem flattering, it is important that names retain their trademark rights and not become generic, as Kleenex, Xerox, and Jell-O did in the private sector.

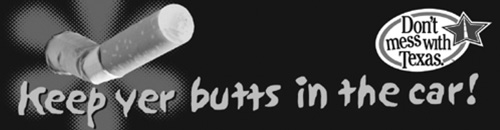

One campaign that has made great choices regarding brand elements to achieve these ideals is the tough-talking litter prevention campaign sponsored by the Texas Department of Transportation—Don’t Mess with Texas®.

As you read the following quote from the official Web site for Don’t Mess with Texas, you’ll get a sense of a desired brand image: “You may wonder how a little saying aimed at educating folks about not dropping candy wrappers and soda cans took on a life of its own—catching on like wildfire and quickly becoming an internationally recognized rallying cry. It’s because the slogan and the campaign advertisements have managed to capture the spirit of Texans themselves. Don’t Mess with Texas says it all. It’s bold. It cuts to the point. It’s full of pride. What others have called braggadocio we Texans call pride ... after all, it ain’t braggin’ if it’s true. We’re crazy about our home state and we want the world to know it.”15

Clearly some of the success in achieving 95 percent name recognition among Texans is due to the selection of campaign elements that reflect this spirit, starting with the selection of the campaign’s name.16 Colors in the campaign logo match those of the state flag (red, white, and blue), and the use of the star symbol with a highway graphic connects it to the flag as well (see Figure 6.11).

Figure 6.11. Litter prevention slogan on the left and the Texas State flag on the right

The campaign uses a variety of ways to make the brand visible, including traditional channels such as television, radio, outdoor billboards, road signs, and special events such as the annual statewide Don’t Mess with Texas Trash-Off. The brand is also supported through more nontraditional strategies, with celebrities including Willie Nelson singing songs for the cause and a Web site that offers bumper stickers and merchandise such as coffee mugs and baseball caps (see Figures 6.12 and 6.13).

Figure 6.12. Don’t Mess with Texas bumper sticker offered free to residents

Figure 6.13. A portion of Don’t Mess with Texas merchandise sales help fund the “Don’t Mess with Texas” litter prevention campaign

Most importantly, the brand supports the state’s objectives to reduce littering. In less than ten years following the launch of the campaign, litter on Texas roadways was reduced by 52 percent. Perhaps the fact that in 2005 the Texas Department of Transportation began cracking down on unauthorized use of the slogan and logo is one additional indicator of the brand’s evolution.

Maintaining a Desired Brand Image

After selecting and designing brand elements, your branding tasks now enter a second phase, that of launching and managing this identity to ensure its intended outcome—a desired brand image. You will need passion for your brand in order to encourage its use and perseverance to take good care of it.

Develop Guidelines for Usage of Brand Elements

The good news for you when you’ve developed a strong brand for your agency or one of its programs is that your fellow colleagues and marketing partners will want to use it. The bad news is they will, and unless told otherwise, they may enjoy taking a little creative license. (Just imagine members of a state’s drowning coalition dressing Smokey Bear up in a swimming suit wearing a life vest and a slogan “Only This Can Help Prevent Drownings!”) You have an internal branding job ahead of you. One effective technique to help ensure a consistent use of all brand elements is to develop (and it can be simple) a style manual, sometimes also referred to as a graphics standards manual or brand identity guidelines. It should inform and assist others in reproducing and displaying the brand. It should inspire them as well.

Smokey Bear is protected with such a guide, providing uniform standards for all aspects of Smokey’s image, from drawings to placements of logos to the manufacture of the costume to public appearances (e.g., the person wearing the costume is not to speak during appearances and should refrain from using alcohol or drugs prior to and during the Smokey Bear appearance). It includes details on acceptable colors, specifying specific numbers within the universal Pantone Matching System (PMS); placement of logos and taglines, including types and sizes of fonts to be used; and the importance of not using Smokey for non-fire prevention messages. The guide also attempts to inspire readers to want to conform to the guidelines, articulating that one of the reasons Smokey continues to be such a powerful icon is because he is carefully managed by those authorized to use his likeness. The standards keep him strong.17

Audit and Manage Brand Contact Points

You’ll have additional internal branding tasks as well because brands are not built (or brought down) by promotions alone. Customers come to know a brand through a range of contact and touch points: interactions with agency personnel and your partners; experiences when online, on the telephone, or performing transactions at your facility; and personal observation and associations when utilizing programs and services.

Consider contact points that Hong Kong International Airport, the world’s fifth busiest international passenger airport, must manage in order to reinforce their official branding as a “dynamic physical and cultural hub with world-class infrastructure.” Experiences that need to be managed to achieve this desired image are expansive and include ease of checking flight arrival and departure information on their Web site; access to transportation by land and sea to and from the airport, requiring coordination and assurance of user-friendly connectivity for arriving passengers as well the 48 million residents of the Pearl River Delta region; time required for checking in for flights; services available while waiting for flights with implications for retail shops, food service, Internet lounges, and children’s play areas; even options for passing the time for longer waits. It doesn’t seem surprising, given this brand promise, that future development adjacent to the airport includes construction of an Asia-World Expo exhibition center, a second hotel project, and even a nine-hole golf course!18

Ensure Adequate Visibility

When launching a new brand or even a revitalized one, adequate exposure of brand elements will be crucial to its eventual orbit and landing in a desired position in the minds of key publics.

The City of Atlanta understands this concept. In February of 2005, an initiative called the Brand Atlanta Campaign was launched, charged with creating a new branding strategy and marketing plan for Atlanta. The Brand Atlanta Group, headed by the city’s mayor, is hoping to put together $4.5 million for the campaign and has raised $1.9 million as of August 2005. Some think it will need more like $10 million. While Atlanta spent $3.2 million on branding in 2003, it is estimated that those considered its peers—Orlando, New Orleans, New York, Chicago—spent an average of $9 million. Las Vegas, a branding leader, spent $51 million.19 Major events are planned to create enthusiasm as well as to raise funds for the campaign, beginning with a “block party” concert where the slogan and new logo will be unveiled and a three-day open house at about 90 museums, art galleries, theaters, and other cultural venues.20

Track and Monitor Your Brand’s Position

To ensure that the brand has landed in the desired position and remains there, you’ll want to keep an eye on it. This may involve a variety of research techniques, ones that will be described in more detail in Chapter 12, “Monitoring and Evaluating Performance.” It will involve research that ideally measures your brand image prior to your efforts and then compares this baseline to results after your launch or repositioning. It will count on your having clearly identified your desired image, giving you a basis for measuring success.

According to one such public opinion survey, Greece has a new identity following the 2004 summer Olympic Games at Athens. It is now seen as a “safe destination” and “modern European country,” and many Americans ranked it as the second most popular destination after Italy. These findings were reflected in the results of a random telephone survey conducted among several thousand citizens in five major countries: the U.S. (1,001 respondents), U.K. (519 respondents), Spain (502 respondents), Germany (507 respondents), and France (502 respondents).21

Stick with It Over Time

If you trace the history of great brands, whether in the public or private sectors, you will most likely find that the common thread is not always one of brilliance or creativity. The common thread is more likely to be that the parent organization simply stuck with something that worked—over time—and that brand trophies more often go to those who nurture and protect brand elements during storms and refurbish them as they begin to age. And the smartest of the bunch understand that just because they’re “bored with it” doesn’t mean it’s not an “old friend” to the marketplace.

How else could a twenty-five year old dog get the privilege of ringing the NASDAQ Stock Market closing bell on Monday, September 26th, 2005? Well, this wasn’t just any dog. It was McGruff the Crime Dog®, and he was celebrating his twenty-fifth birthday. This is the brand that encourages and teaches Americans how to “Take A Bite Out of Crime,”® one recognized by about four out of five adults and considered friendly, trustworthy, smart, caring, and helpful by four out of five children who know him (see Figure 6.14).22 The idea of a national campaign to persuade citizens that they can prevent crime—and how to do so—was first conceived in 1978. The U.S. Department of Justice supported the plan, as did organizations such as the FBI, the International Association of Chiefs of Police, the National Sheriffs’ Association, the AFL-CIO, and the Advertising Council who developed powerful public service advertisements with the volunteer help of Saatchi & Saatchi, an advertising agency. The National Crime Prevention Council, a private nonprofit organization, serves as the day-to-day manager of the campaign, which is funded through a variety of government agencies as well as corporate and private foundations and donations from private individuals. It is one of the most successful public service campaigns in history, with a recent identity theft initiative funded by the Department of Justice to help consumers take practical steps to protect their personal information.

Figure 6.14. McGruff the Crime Dog® helping Americans “Take A Bite Out of Crime”®23

Revitalizing or Reinventing a Brand

Changes in citizen preferences, new competitors, new findings or new technology, or any new major development in the marketing environment could potentially affect the fortunes of your brand. Reversing a fading or floundering brand’s destiny requires that you return to the brand’s roots if they are strong and (pursuing the analogy) prune any dead wood, work in a lot of nutrients, and give it a good soaking. If, however, chances for revival are slim, it’s probably time to find new sources of brand equity and emerge anew. Regardless of which approach is taken, brands on the comeback trail will need to make revolutionary change. Often, the first thing to do is to understand what the sources of brand equity were to begin with. Are positive associations losing their strength and uniqueness, or are they just buried too deep? Have any negative associations such as ones with product performance, service quality, partners, or any spokespersons become linked to the brand? Decisions must then be made as to whether to retain the same positioning or create a new one. There is obviously a continuum involved with pure “back to basics” and revitalization on one end and pure reinvention at the other, illustrated in the following two examples.24

Revitalizing a Brand

The Drug Abuse Resistance Education (D.A.R.E.) program is an extensive substance abuse prevention delivery system that operates in 75 percent of all school districts in the United States and reaches over 26 million young people worldwide by bringing police officers into the classroom. In the face of studies questioning, even criticizing, the impact of the program, and to help teachers and administrators cope with ever-evolving federal prevention program requirements, it has been recalibrated. “Gone is the old-style approach to prevention in which an officer stands behind a podium and lectures students in straight rows. New D.A.R.E. officers are trained as ‘coaches’ to support kids who are using research-based refusal strategies in high-stakes peer-pressure environments (see Figure 6.15). New D.A.R.E. students of 2004 are getting to see for themselves—via stunning brain imagery—tangible proof of how substances diminish mental activity, emotions, coordination and movement. Mock courtroom exercises are bringing home the social and legal consequence of drug use and violence.”25 The new brand promise, reflected in the words of their Chief Executive Officer, is to be “effective, diverse, accountable and mean more things to more people.”26

Figure 6.15. Promoting the revitalized D.A.R.E. program27

Reinventing a Brand

Al Ries and Jack Trout, mentioned earlier in this chapter, were authors of a classic book in the ’80s titled Positioning: The Battle for Your Mind. One of the inspirational stories they share is of their involvement in helping to position the island of Jamaica as a premier destination for tourists.

Although the prime minister at the time was most interested in positioning the island for capitalistic investments, Ries and Trout argued they should focus first on tourism, with the rationale that many tourists work for big companies, and if they came back from Jamaica with favorable impressions, it just might encourage investments on the island. Their first exercise, as they described it, was to look in the mind of the prospect to see what mental images already exist and then select one to tie Jamaica into. They discovered the “verbal essence” of Jamaica was best characterized as “a big green island in the Caribbean that has deserted beaches, cool mountains, country pastures, open plains, rivers, rapids, waterfalls, ponds, good drinking water, and a jungly interior.” They then posed what might seem like the obvious questions: “Does that sound familiar? Does it remind you of a very popular tourist destination in the Pacific?”

In the end, as you might have guessed, they recommended positioning Jamaica as “The Hawaii of the Caribbean,” a position that would strongly and authentically differentiate Jamaica from the other competitive Caribbean destinations as well as provide a solid platform for steering European travelers to an option closer to home than the Pacific.28

Summary

You began this chapter with exposure to a variety of definitions related to branding. Most important to recall is that a brand identifies the maker or seller of a product, that brand identity is how you want consumers to see your brand, and that brand image is how they actually see it. You will have a brand image whether you intend to or not. Most important to take away from this reality is that you want your brand image to be one that you want, one that is deliberate. Six steps were recommended to accomplish this:

- Establish the brand’s purpose for your organization.

- Identify target audiences for the brand.

- Articulate your desired brand identity.

- Craft the brand promise.

- Determine the brand’s position relative to the competition.

- Select brand elements.

You also read recommendations for maintaining a desired brand image: develop guidelines for usage of brand elements, audit and manage brand contact points, ensure adequate visibility, track and monitor your progress, and stick with (a good one) over time.

If you find yourself with a fading or floundering brand, but you aren’t “putting it out of business,” you will need to evaluate whether to revitalize or reinvent it, both of which most likely will require revolutionary change.