6

Designing for Results

This chapter focuses on designing the technology-based learning program to deliver results. Program design has an important connection to the results achieved. This concept involves designing the appropriate communication about the program, changing the role of participants, creating expectations, and designing specific tools and content to make the project results based. This final chapter of the ROI Methodology focuses on these tools for the designer.

COMMUNICATING WITH RESULTS IN MIND

![]()

When a learning program is implemented, a chain of communications begins. These communications describe what is expected from the program, for all who are involved. The principal audience for communication is the individuals who will make the program successful; they are often labeled as the participants. The managers of these participants, who are expecting results in return for the participants’ involvement in the program, are also a target for information. At least four areas of communication are important.

Announcements

Any announcement for the program—whether a verbal announcement, online blurb, ad, email, or blog—should include expectations of results. In the past, the focus of the announcement may have been on the program’s content or learning objectives; this is no longer the case. The focus now is on what individuals will accomplish with a project and the business impact that it will deliver. The measure should be clearly articulated so it will answer the participant’s first question, “What’s in it for me?” This clearly captures the results-based philosophy of a particular program.

Brochures

If the project is ongoing or involves a significant number of participants, a brochure (digital or paper) may be developed. A brochure is typical for programs that are very important, strategic, and expensive. These brochures are often cleverly written from a marketing perspective and are engaging and attractive. An added feature should be a description of the results that will be or have been achieved from the program, detailing specific outcomes at the application level (what individuals will accomplish) and the impact level, as well as the consequences of the application. These additions can be powerful and make a tremendous difference on the outcome of the program.

Memos

Correspondence to participants before they become fully engaged with their program is critical. These memos and instructions should outline the results described in the announcements and brochures, and focus on what individuals should expect when they become involved in the project. When prework is necessary for participants to connect with the program, the focus should be on the results expected. Sometimes participants are asked to bring specific examples, case studies, problems, measures, or business challenges. Communications should be consistent with the results-based philosophy, underscore the expectations and requirements, and explain what must be achieved and accomplished. Also, the request to provide feedback and document results is explained to participants, emphasizing how they will benefit from responding.

Workbooks

Workbooks are designed with higher-level objectives in mind. Application and impact objectives influence the design of exercises and activities as they emphasize results. Application tools are spaced throughout the workbook to encourage and facilitate action. Impact measures, and the context around them, appear in problems, case studies, learning checks, and skill practices.

CHANGING THE ROLE OF PARTICIPANTS

![]()

Perhaps there is no more important individual who can achieve business success than the participant involved in the program. The participant is the person who is learning the skill and knowledge needed for a job setting that will subsequently drive business performance. The participant is the person who is involved in the implementation to achieve the results all the way through business impact. It is often the mindset of this person (in other words, the readiness and motivation of this individual to achieve success) that will make a difference. Sometimes this starts with changing the role of this person, defining more clearly what is expected and perhaps expanding expectations beyond what is traditionally required.

Why This Is Necessary

Many programs and projects fail because the individuals involved didn’t do what they were supposed to do. While there are many barriers to achieving success, including those in the workplace, perhaps the most critical one is that the person involved did not want to, did not have time to, or did not see any reason to do what is necessary to achieve success. While they normally blame others (and not themselves), the participant may actually be the problem. The efforts of the participant must change, and this involves two issues, which are described next.

Defining the Role

The first issue is to define the role of the participant, clearly outlining what is expected. For technology-based learning, participants should always understand their specific roles. Table 6-1 describes the new and updated role of a participant. This role clearly defines what is expected throughout the process and engages the participants in expectations beyond the learning sessions. It suggests that the success is not achieved until the consequence of application is obtained, identified as specific business improvements. Most importantly, the role requires participants to provide data. It is only through their efforts and subsequent information that others will understand their successes. At the same time, the participant will clearly see the success of the program.

TABLE 6-1. The Role of the Participant

1. Be prepared to take advantage of the opportunity to learn, seeking value in any type of project or program.

2. Enroll, be on time, stay fully engaged, and become a productive participant.

3. Look for the positives in the program and focus on how the impediments can be removed.

4. Meet or exceed the learning objectives, fully understanding what is expected.

5. Share experiences and expectations using virtual tools, if available, recognizing that others are learning from you.

6. Plan to apply what is learned in a workplace setting.

7. Remove, minimize, or work around barriers to application and success.

8. Apply the learning in a workplace setting, making adjustments and changes as necessary to be successful.

9. Follow through with the consequences of application, achieving the business results from the program.

10. When requested, provide data that show your success as well as the barriers and enablers to success.

Documenting the Roles

The role of the participants should be clearly documented in several places. For formal learning sessions in a blended format, the role is sometimes placed on the name tents so that it is clearly visible at all times during the workshop. In other cases, the role is presented as a handout or downloadable document in the beginning of the program, outlining what is expected of the participant all the way through to impact and results. Sometimes it is included in the workbook material, usually on the first page. It is also placed in catalogs of programs where program descriptions are listed. The role can be included as an attachment to the registration documents as participants are enrolled in a program. It is often included in application documents, reminding the participant of his or her role. Finally, some learning centers place the roles in each conference room so they are clearly visible. The key issue in documenting roles is to place them permanently and prominently so that they are easily understood.

CREATING EXPECTATIONS

![]()

With the roles of participants clearly defined, expectations are created. The challenge is to let participants know what is expected and to avoid any surprises throughout the process. Participants resist surprises involving assignments, application tools, or action plans. Also, when a questionnaire, interview, or focus group is scheduled on a post-program basis, participants often resent these add-on activities. The approach is to position any necessary actions or data collection as a built-in process and not an add-on activity.

Identifying Measures Before the Program

For some projects, the participants define the specific business measures that need to improve. For example, in a supervisor safety program implemented in all plants, participants are asked to identify the safety measures that need to improve, but only if those measures can be changed by working with their team using the content of the program. Although this approach may seem dysfunctional, it represents the ultimate customization for the participant, and it applies to many programs. The implementation of lean Six Sigma, for example, requires participants to identify specific business measures that they want to improve by making a process more efficient or effective. Impact measures are identified and become part of the project undertaken by the participant. In the classic GE workout program, pioneered by GE’s former chairman, Jack Welch, the participants identified specific projects that needed to improve. All types of process improvement and performance enhancement efforts have this opportunity, ranging from negotiations, creativity, innovation, problem solving, communication, team building, coaching, leadership development, supervisor development, management development, and executive education, among others. This creates the expectation and often comes with a pleasant reaction, because the participant focuses on the measure that matters to them.

Involving the Managers

In addition to creating expectations directed to participants, the participants’ managers may be involved. Participants may be asked to meet with their manager to ensure that the manager has input into the involvement in the program. Sometimes this includes an agreement about what must improve or change as a result of the program. One of the most powerful actions that can be taken is having the managers set goals with participants prior to the programs. Another opportunity for manager involvement is to develop a module just for the manager. This is usually a shortened version of the participant module.

Messages From Executives

In addition to immediate manager involvement, having others in executive roles to create expectations can be powerful. In most organizations, the top leaders are often highly respected, and their requirements or expectations are not only noticed, but are often influential. Figure 6-1 shows an opening announcement from a CEO about a safety project. The opening speech was recorded and presented virtually, clearly positions the expectations for business connections, removing any doubt of what was expected. The message is clear: Participants must learn new approaches and tools that they will use or implement; but ultimately, success must be achieved at the business level.

FIGURE 6-1. CEO Message and Expectations

Thank you for taking the time to become involved in this important e-learning project. I am confident that this is the right time and the right place to achieve some major safety improvements. Although we have a safety record that is among the best in the industry, there is still room for much improvement, and it is unacceptable in our minds and in your minds. There is no way we can be pleased with any lost time injuries, let alone a fatality in our workplace.

We have a dozen business measures that you are reviewing in this particular project. The focus of this project is to improve as many of these as possible. The measures will be ranked in the order of the seriousness in terms of pain and suffering for employees and also cost and disruption at the workplace. We expect you to make significant improvements in these measures.

During this project, you will be exposed to a variety of techniques and processes to achieve success. You have our support to make it a reality. Here are our SMART goals for the next two years.

| Measure | Reduction |

| Fatalities | 50% |

| Lost time injuries | 12% |

| Accident severity rate | 12% |

| OSHA reportable injuries | 13% |

| OSHA fines | 18% |

| First aid treatments | 23% |

| Near misses | 16% |

| Property damage | 29% |

| Down time because of accidents | 18% |

I have confidence in you to accomplish these goals with this program. You have my full support. You have the full support of our safety and health team. And you have the full support of your operating executives. There is nothing that we won’t do to assist you in this effort. If you have a problem or issue that you need to get resolved and you are having difficulty, contact my office and I will take care of it.

The improvement in these measures is on your shoulders. Only you can do this. We cannot do it at a distance and our safety and health team cannot do it alone. It is your actions with your employees that can really make a difference.

Good luck. We look forward to celebrating these successes with you.

DESIGN FOR RELEVANCE

![]()

Blended learning, e-learning, and mobile learning will usually include the acquisition of important knowledge and skills. A prerequisite to achieving results is to make sure that the program is designed for proper relevance.

Sequencing the materials from easy to hard, or for the natural flow of the learning, is helpful. Advanced material is placed near the end. Small quantities of information should be presented sequentially, keeping a balance so not too much content is offered, but enough to keep the individuals challenged.

The content should come at the right time for participants, ideally, just before they need to use it. If it is presented too early, it will be forgotten; and if it is too late, they will have already learned another way to do it. The content must relate to the participants. It must have relevance to the job. Essentially, the challenge is to focus on achieving customized learning to the individual, following the J4 approach:

1. Just for me.

2. Just in time.

3. Just enough.

4. Just right for the task.

DESIGN FOR RESULTS

![]()

After designing for learning comes the focus on results. The two issues are connected. As the program is designed for participants to learn the content, the focus shifts ultimately on the business results. At least five areas require attention.

Activities

All activities should focus on situations that define the application of what participants are learning, the consequences of their learning, or both. Activities, exercises, individual projects, and any other assignments should focus on the actions that participants will be taking on the job to achieve business success.

Skill Practices

Sometimes participants will practice skills where the focus is on the use of those skills and the subsequent outcomes. The situational context for the practice is critical for achieving business results. For example, if a learning session is focused on improving employee work habits, a distinct set of skill sets are developed for changing these habits. To provide the focus, an impact objective is needed to define the original problem that must be changed. In one setting, it was absenteeism and tardiness. With that objective known, the skill practices are designed to improve an existing measure of unplanned absenteeism and persistent tardiness, both captured in the system. Without the impact objectives, the skill practice could be focusing on situations where other unrelated work habits and outcomes could be the problem, such as excessive talking, excessive texting, improper dress code, and other distracting habits. The impact objectives clearly defined the problem and signaled for the designer to include absenteeism and tardiness in the skill practices.

Simulations

When simulations are developed to measure learning, they should describe and connect with the ultimate outcomes. This extra effort makes the simulation as real as possible for application and keeps an eye on the consequences (business impact). For example, simulations with the use of software are not only replicating what the participant is doing, but reporting time taken to accomplish steps (time), errors that are made along the way (quality), and the level of accomplishment achieved (productivity). These simulations remind the individuals about the ultimate outcome, business results.

Problems

Some programs involve solving problems, particularly if the program is process oriented. The problems provided should reflect a realistic connection to application and impact. The related activities should focus on a problem that participants will be solving and the measures that they will be improving as the problem is solved, such as output, quality, cost, and time. For example, in an advanced negotiation program, participants were asked to solve a negotiation problem. Given the ultimate outcome needed for the negations (budget, delivery, and quality), the participants used the appropriate skill sets to ultimately achieve their negotiations in a planned process. In solving the problem, participants had to identify the specific skill sets that would be used (application), and arrive at the correct amount for each outcome (business impact).

Case Studies

Case studies are often a part of a learning program. They bring to light real situations. Case studies should be selected that focus on the content, application, and impact for the program. Application items and impact measures should be scattered throughout the case study. The case study includes them, focuses on them, and often results in recommendations or changes to them. This reminds the audience of the ultimate impact that should be an important part of the process.

BUILT-IN APPLICATION TOOLS

![]()

Building data collection tools into technology-based learning is perhaps one of the most important areas where designing for results works extremely well. This is particularly helpful for blended learning and e-learning programs where data collection can easily be a part of the program. Ranging from simple action plans to significant job aids, the tools come in a variety of types and designs. They serve as application and data collection tools.

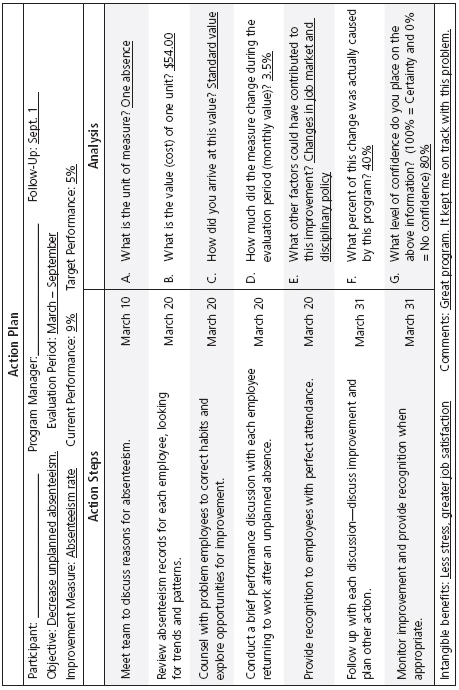

Action Plans

A simple process, the action plan is a tool that is completed during the program, outlining specifically what the participant will accomplish after the program is completed and during its implementation. The action plan always represents application data and can easily include business impact data where a business measure will be improved. Figure 6-2 shows an action plan where the focus is directly on improving a business measure. In this example, unplanned absenteeism in a call center is being improved from a high of 9 percent to a planned level of 5 percent. The actions listed in the plan on the left side of the document are the steps that will be taken to improve the business measure. The information on the right focuses more detail on the data, including the value it delivers. While this tool serves as a data collection process, it also keeps the focus on business impact. As the data are collected, it can even be used to isolate the effects of the program on the impact data, validating that the business alignment did occur. For this to work extremely well, several steps must be taken before, during, and after the action plan to keep the focus on business impact. Figure 6-3 shows the steps that are followed to ensure that the action plan is built into the process and becomes an integral part of achieving the business success.

FIGURE 6-2. Example of Action Plan

FIGURE 6-3. Sequence of Activities for Action

| Before |

• Communicate the action plan requirement early. • Require business measures to be identified by participants. |

| During |

• Describe the action planning process. • Allow time to develop the plan. • Teach the action planning process. • Have the program manager approve the action plan, if possible. • Require participants to assign a monetary value for each proposed improvement (optional). • If possible, require action plans to be presented virtually to the group. • Explain the follow-up mechanism. |

| After |

• Require participants to provide improvement data. • Ask participants to isolate the effects of the program. • Ask participants to provide a level of confidence for estimates. • Collect action plans at the predetermined follow-up time. • Summarize the data and calculate the ROI (optional). |

Improvement Plans and Guides

Sometimes, the phrase “action plan” is not appropriate, if organizations have used it to refer to many other projects and programs, possibly leaving an unsavory image. When this is the case, other terms can be used. Some prefer the concept of improvement plans, recognizing that a business measure has been identified and improvement is needed. The improvement may represent the entire team or an individual. There are many types of simple and effective designs for the process to work well. In addition to improvement plan, the term “application guide” can be used and can include a completed example as well as what is expected from the participant, including tips and techniques along the way to make it work.

Application Tools/Templates

Moving beyond action and improvement plans brings a variety of application tools, such as simple forms to use, technology support to enhance an application, and guides to track and monitor business improvement. All types of templates and tools can keep the process on track, provide data for those who need it, and remind a participant where he is going.

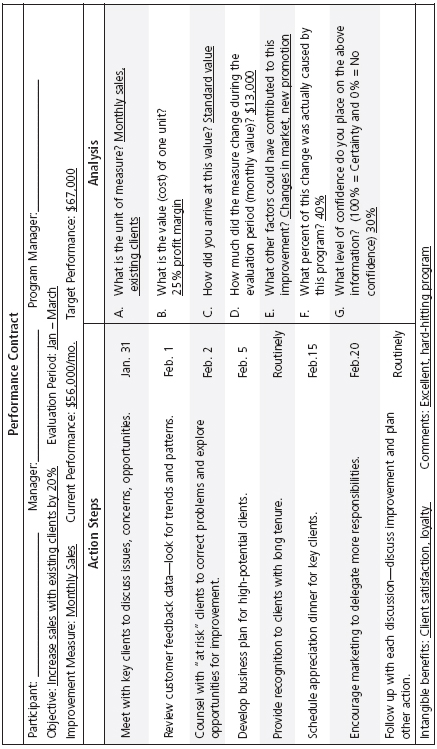

Performance Contract

Perhaps the most powerful built-in tool is the performance contract. This is essentially a contract for performance improvement between the participant in the project or program and her immediate manager. Before a program is conducted, the participant meets with the manager and they agree on the specific measures that should be improved and the amount of improvement. Essentially, they agree on an improvement that will result in the use of the content, information, and materials of the program. This contract can be enhanced if a third party enters the contractual arrangement (this would normally be the program manager for the technology-based learning program).

Performance contracts are powerful, as these individuals are now committing to performance change that will be achieved through the use of content and materials from the program, and has the added bonus of support from the immediate manager and from the facilitator or project manager. When programs are implemented using a performance contract, they are powerful in delivering very significant changes in the business measure.

The design of the performance contract is similar to the action plan. Figure 6-4 shows a performance contract for a sales representative involved in a blended learning program, including a combination of formal learning sessions, online tools, and coaching from the sales manager. The goal is to increase sales with existing clients. The sales manager approves the contract along with the participant and the program manager.

Job Aids

Job aids represent a variety of designs that help an individual achieve success with application and impact. The job aid illustrates the proper way of sequencing tasks and processes and reminds the individual of what must be achieved, all with the ultimate aim of improving a business measure. Perhaps the simplest example is the job aid used at a major restaurant chain, which shows what must go into a particular dish ordered by a customer. The individuals preparing the food use the job aid, which was part of a learning program. The job aid shows how the process flows, using various photographs, arrows, charts, and diagrams. It is easily positioned at the station where the food is prepared and serves as a quick reference guide. When used properly, the job aid is driving important business measures: keeping the time to fill the order at a minimum (time savings), allowing the restaurant to serve more customers (productivity), and ensuring consistency with the meal and reducing the likelihood of a mistake being made on the order (quality).

USE TRANSFER TOOLS

![]()

A variety of tools are available to keep the participant engaged and focused on the transfer of learning to the job (application and impact). Figure 6-5 provides a list of techniques to enhance results from learning.

FIGURE 6-4. Example of Performance Contract

FIGURE 6-5. Examples of Application Techniques

| Making Learning Stick | |

| Action Learning | Sticky Blog |

| Action Plans | Sticky Heat Map |

| Application Checks | Sticky Kit for Managers |

| Do Not Disturb | Sticky Learning Community |

| Do Now | Sticky Microblog |

| Feel-Felt-Found | Sticky Objectives |

| KISS: Keep It Simple or Supervised | Sticky Wiki |

| A Little Help From Friends | Strategy Link |

| Live Pilot | Thank-You Note |

| Manager Module | Threaded Discussion |

| Note to Self | Transfer Certificate |

| Picture This | Virtual Tutor |

| Pop-Up Reflections | What’s Wrong With This Picture? |

| QR Codes | Wrap It Up |

Source: Carnes, B. (2012). Making Learning Stick: Techniques for Easy and Effective Transfer of Technology-Supported Training. Alexandria, VA: ASTD Press.

INVOLVING THE PARTICIPANT’S MANAGER

![]()

A final area of design involves creating a role for the managers of the participants. As mentioned earlier, this is a very powerful group and having specific items, activities, tools, and templates for them can make a tremendous difference in business results.

The Most Influential Group

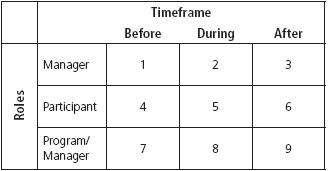

Research has consistently shown that the managers of a group of participants are the most influential group in helping participants achieve application and impact objectives, apart from their own motivation, desire, and determination. No other group can influence participants as much as their immediate managers. Figure 6-6 shows how learning is transferred to the job, using three important groups of stakeholders involved in this success: participants, their immediate managers, and the program manager. Three timeframes are possible: prior to the program, during the program, and after the program.

This matrix creates nine possible blocks of activities to transfer what is learned from a particular program to the job. The transfer not only includes the behaviors and actions that must be taken (application), but also the impact that must be obtained (impact measures). For example, the participant can be involved in preprogram activities to set specific goals to achieve before the program is implemented (block number 4). During the program, the participant will plan specific actions to improve a business measure (block number 5). After the program is conducted, the participant will apply the material, achieve the business impact improvement, and report it to interested stakeholders (block number 6).

FIGURE 6-6. The Transfer of Success to the Job

In another example, the manager can meet with the participant and set a goal before attending the program (block number 1). During implementation, the manager completes a manager’s module or provides coaching as part of it (block number 2). After the program, the manager follows up to make sure the material is used appropriately and the business impact has been achieved (block number 3). The process continues until activities are identified for every block.

Research on this matrix shows that the most powerful blocks for achieving learning transfer to the job are blocks 1 and 3. Unfortunately, managers do not always see it that way. They underestimate their influence. They must be reminded of their influence and provided tools that take very little time to apply to ensure the result of the project is used and drives the business results. This is one of the most powerful areas to explore for improving business results.

Preprogram Activities

At the very least, managers should set expectations for participants involved in any type of activity, program, project, event, or initiative. It only takes a matter of minutes to set that expectation, and the results can be powerful. Preprogram activities can range from a formal performance contract, described earlier, to an informal, two-minute discussion prior to being involved in the program. A full array of activities should be provided that take very little time. Even a script could be helpful. The important point is that managers must be reminded, encouraged, or even required to do this.

During-the-Program Activities

Sometimes, it is important for the manager to have input into the design and development of the program. Possible activities include having managers (or at least someone representing the manager group) help design program content. Also, managers could review the content and serve as subject experts to approve it. Managers could be involved in a manager’s module, learning parts of the process, providing one-on-one coaching for participants needing help with specific parts, or just observing the program (or a portion of it). Managers could serve on an advisory committee for the program or review the success of others in the program. The key is to connect the manager to the design and content of the program. Manager involvement will help focus the program on business results, which they will find extremely important.

Post-Program Activities

The most basic action a manager can take is to follow up to ensure the content of the project is being used properly. Suggesting, encouraging, or even requiring application and impact can be very powerful. Managers should be available to provide assistance and support as needed to make the program successful. Just being available as a sounding board or to run interference to ease the application may be enough. Although not necessary, post-program activities can be more involved on a formal basis, where managers actively participate in follow-up evaluations. Managers may sign off on results, review a questionnaire, follow up on action plans, collect data, or present results. In any case, they make a difference.

Reinforcement Tools

In some situations, a management reinforcement workshop is offered to teach managers how to reinforce and guide the behaviors and actions needed to achieve a desired level of performance in business measures. Reinforcement workshops are very brief, usually ranging from two to four hours, but can be extremely valuable. In addition to the workshops, a variety of tools can be created and sent to managers. The tools include checklists, scripts, key questions, resources, and contacts needed to keep the focus on results.

Sometimes managers volunteer for a coaching role where they are asked to be available to assist the participants with a formal coaching process. In this scenario, managers are provided details about coaching, how to make it work, and what is required of them. This is extremely powerful when a participant’s immediate manager serves as a coach to accomplish business results.

FINAL THOUGHTS

![]()

This chapter focused on what is necessary to achieve business results from a design perspective—designing the communications, expectations, roles, content, and tools that are necessary for a participant to be fully involved. A program with the proper design, combined with a participant who is motivated to learn, will make achieving success a reality. Participants will explore connections to use the acquired knowledge and increase the tenacity to implement the tools and techniques. This approach provides the readiness, motivation, commitment, and tools needed to help achieve business alignment. The remainder of the book presents case studies.

For more detail on this methodology, see The Value of Learning: How Organizations Capture Value and ROI and Translate Them Into Support, Improvement, Funds (Phillips and Phillips, 2007, Pfeiffer).