1

Learning Through Technology: Trends and Issues

It’s hard to imagine a world of learning and development without technology-based solutions. Imagine a U.S.–based technology company with 250 product launches each year and a need to train the sales team to sell the new product. Bringing the sales team into the classroom environment would be prohibitive in terms of cost, time, and convenience. It is unimaginable that we would do that 250 times during the year with the entire sales team. Technology makes learning easy, convenient, and inexpensive. Imagine a logistics company with 300,000 employees and a need to make all employees aware of a new compliance regulation. The regulation requires some evidence that each employee actually knows this information. A live, face-to-face briefing or an email would be out of the question. Technology makes it happen.

Imagine employees in remote locations in Alaska who need job-related learning. The cost of either bringing them to the classroom or bringing the classroom to them would be prohibitive, and it would also be inconvenient and time-consuming. Technology makes it happen. Imagine that women at a university in the Middle East, unable to attend a live class because it is taught by a male instructor, have no opportunity to take the course. With online learning, the same course is possible for women.

These types of situations are multiplied thousands of times throughout the global landscape. It is difficult to imagine a world of learning and development without technology, and investment in technology continues to grow at astonishing rates. These investments attract attention from executives who often want to know if they’re working properly. Executives who have sales teams participate in new product training are concerned that the learning translates into new sales. “Does it make a difference? How does it connect to the business? Does it really add the value that we anticipated? Is it as effective as facilitator-led learning?” These questions and others are fully explored and answered in this book. It’s all about how to measure the success of learning through technology. This opening chapter describes the trends and issues for technology-based learning and the need for accountability.

THE EVOLUTION OF LEARNING TECHNIQUES

![]()

Technology has been integrated into our lives, both at home and at work. It has dramatically changed how we communicate, how we spend our money, how we spend our time, how we work, how we play, and how we find out more about the world in which we live. But what does this mean for corporate learning, training, and development?

Learning technologies have been used in the workplace for more than 20 years, but it is only in the last few years that their impact could be described as a “fundamental change.” This book explores some of the more recent evolutions of learning technology and how it can bring significant change in how we grow and develop our current and future employees.

For as long as we can remember, companies have been training and developing employees, helping them master the skills needed to do their work. What originally started as apprenticeships evolved toward more centralized training as companies grew in size and complexity. Experts were brought to classrooms full of employees to teach them the skills needed to do their jobs better. Much of this early training followed the traditional “knowledge broadcast” model, with the expert on the stage presenting what he knows. Early learning technologies such as projectors, digital presentations, and training videos fit this model well.

In the late 1990s, the rise of the Internet gave a huge boost to “digital content.” Suddenly, it was much easier to create and share content around the world. This led to the growth of two very different types of stakeholders: content specialists, who developed and sold learning content in their areas of expertise (for example, financial management); and systems specialists, who developed learning platforms or learning management systems (LMS), which allowed companies to deliver online learning to employees around the world at any time.

Broadly, this was a success. Companies were putting more and more of their training online and were able to reach an increasingly diverse group of learners. The next 10 years were vibrant days for learning technologists, with companies investing heavily in e-learning, excited by the potential cost savings of no more face-to-face training. During this time, hundreds of new e-learning companies formed, merged, and were acquired. Digital content became commoditized and was increasingly bought in segments, either by the hour or by an amount of content. There was little regard for the learning quality itself. Unfortunately, as with many new technologies, a large number of overly enthusiastic training departments forged ahead with this technology trend and mistakenly thought that some badly—e-learning courses would somehow be as effective as expert face-to-face training sessions—they were not!

From the mid-2000s the e-learning market started to mature with the addition of three new ideas and associated technologies:

1. Shift from training delivery to talent management: Some of the leading LMS vendors started to add enhanced features to their platforms to appeal to HR and training departments. These platforms evolved into “talent management platforms,” which included features like employee development plans and talent management tools. Their popularity grew rapidly, since both companies and employees were becoming increasingly dissatisfied with using “course completions” as a meaningful criterion for successful employee development.

2. Increased use of blended learning: Digital content and LMS-style platforms don’t work just for remote learners. In fact, they are most effective when used in combination with a face-to-face classroom experience. After an initial frenzy of “do it all online,” many training professionals discovered that the best use of these new technologies was to enhance traditional training, not replace it. The technologies didn’t change much, but how they were used did!

3. Virtual classrooms, video streaming, collaboration tools: As the use of social media grew and video tools like Skype and WebCT entered the mainstream, trainers were able to mix more of the benefits of a face-to-face training class with the reach of a web-based learning platform. Students from all over the world could log on together to a live session and participate in online discussions.

These three ideas helped e-learning evolve into a more useful business tool and consolidate a small number of big players, who offer platforms that can deliver on all of these features. But this only gets us to 2010. Who are the learning technology leaders that are prepared to replace these big players? What are the emerging innovations in learning technology?

Mobile Learning

Much hyped but only moderately understood, mobile learning involves mobile devices woven into a learning or training scenario. Often, but not always, the learners themselves are mobile. Mobile learning has found significant success in areas where traditional training or learning are not working that well (such as hard-to-reach learners or traveling employees). It has also triggered a rethink about traditional e-learning modules. Mobile is great for instantaneous lookup, and small, chunk-based learning, but a poor tool for a drawn-out e-learning course.

The most important aspect to bear in mind is that mobile learning isn’t just one thing. It is a toolbox of approaches that can be used how and when it’s needed. Conversations about mobile learning in schools are likely to be very different from those in the college or work setting.

Mobile learning is already making a huge impact in some industries and in specific areas. It will continue to do so, but don’t assume it replaces all face-to-face experiences. Think of it more as an enriching and enhancing aspect of training.

Game-Based Learning

Game-based learning has been described as the next big thing for the past 10 years. Two often repeated disastrous models are:

• An interesting game, often a first-person adventurer/puzzle-solving variety, with corny 2-D content quizzes scattered throughout. A fun game ruined by insufficient learning.

• A linear e-learning-style content course with a series of quizzes and knowledge tests that have been built up into a contest/competition format. The “game” just proves content knowledge.

There is very little evidence that either of these models works. There are a few instances where the latter can work well, such as where mastery of the subject matter required drill and practice (like learning vocabulary or practicing math).

Two interesting and more successful models are:

• Playing a real game, designed for entertainment, but setting challenges within it that build on learning.

• Doing real learning tasks, but using a badging system to show progress and gains. Mozilla’s Open Badges framework offers good tools for this.

Mixing play with learning has always been effective and will continue to be so. But low-quality resources aren’t magically improved by adding a quiz at the end, a leaderboard, or badges. Get the learning right first, then implement around it.

Bring Your Own Devices (BYOD)

“Bring your own devices” (BYOD) refers to initiatives that allow students or employees to use their own personal mobile technology devices at work or at school as part of their day. Opinions about this technique vary widely, although in most scenarios it is a useful and empowering approach. In colleges, the main concerns are about classroom management and fairness of access. In the workplace, concerns range from privacy of personal data to security of corporate data. BYOD is here to stay. Organizations need to adapt their policies to support it, rather than resisting the use of personal mobile technology devices. Resistance puts them in a race to provide equivalent devices and access.

Open Educational Resources (OER)

Historically, there has been an uncomfortable relationship between publishers and educators. Who owns the rights to the content used during teaching and training? How much should be paid for the books and resources?

Enter the OER movement—open educational resources that can be used, modified, and shared for free. They’re mostly used in the context of traditional education (not much in corporate training). Momentum seems to be moving faster in some countries than others, but many heavyweight backers, funders, and institutions are starting to put their money and weight behind the idea that educational resources should be made available for free.

It is still a fairly disconnected movement with many different stakeholders and various definitions of “free” and “open.” But a large range of very good resources and publications have already been made available. In some cases, teams of educators are working together to write their own collaborative textbooks as open alternatives to commercial ones.

Of note is Creative Commons, which offers a very simple licensing model to help users understand exactly how free content can be used and reused while still respecting the creator of the content.

Massive Open Online Course (MOOC)

A MOOC is a web-based course, often free, designed to offer learning to many thousands of students at the same time. Although they have been around since 2008, they have received a lot of attention since 2012, thanks to recent backing from some notable schools (Stanford, Princeton, and MIT, for example) and high-profile start-ups. However, the most recent hype is also slightly skewed to one specific genre of MOOC.

Why is everyone suddenly excited about MOOCs? Several schools have started offering free access to their course materials. This is a real-world case of the democratization of learning. A student at an under-resourced school can now access the same content as an MIT graduate. However, the fast pace of change hasn’t taken into account some of the unforeseen issues surrounding this broadened access. Once access to education is opened up and notions of paying for courses are removed, is the perceived quality of the course reduced? Should a nonresident student be able to earn a degree from the college offering a course? Is distance learning devoid of a pastoral context equivalent to the full collegiate experience? The debates surrounding MOOCs have compromised the perception of them. Some see them purely as a distribution channel for prerecorded mass learning. Many of the most inspired MOOCs are not modeled on a traditional lecture- or classroom-based experience at all; rather, they’re built on learner-centered, connectivist environments where students work together, albeit remotely.

To try to distinguish between these, one of the founders of the MOOC move- ment has suggested renaming them xMOOC and cMOOC. xMOOCs are modeled on a traditional lecture-based experience, with professors handing over the knowledge; and cMOOCs are collaborative courses, where learners work together the generate their knowledge.

For the purposes of this discussion we have coined a new term, domain MOOCs. These are MOOCs designed for individual access, to teach a specific subject by making the content available for free, to be used in other platforms. Aligned with these are sites offering indexes to all of these courses, styling themselves as MOOC aggregators.

Flipped Classroom

If so much information is available online and quality time with a teacher is hard to find, why waste the time you have together by sitting quietly in your chair and listening to a lecture? Far better, perhaps, to watch the recorded lecture before you come into class and then spend the face-to-face time discussing it, asking questions, and doing activities. This is the idea behind the flipped classroom, and it has some great stories around it.

CONCERNS ABOUT TECHNOLOGY-BASED LEARNING

![]()

Technology, with its many forms and features, is here to stay. Its growth is inevitable and its use is predestined. At the same time, some concerns must be addressed about the accountability and success of technology-based learning. Three critical issues create a dilemma: the need for business results, the executive view, and a lack of results.

The Need for Business Results

Most would agree that any large expenditure in an organization should in some way be connected to business success. Even in nonbusiness settings, large investments should connect to organizational measures of output, quality, cost, and time—classic measure categories of hard data that exist in any type of organization. In a review of articles, reports, books, and blogs about learning through technology, the emphasis is on making a business connection. For example, in the book Learning Everywhere: How Mobile Content Strategies Are Transforming Training (2012) author Chad Udell makes the case for connecting mobile learning to businesses measures. He starts by listing the important measures that are connected to the business. A sampling is shown in Table 1-1.

Udell goes on to say that mobile learning should connect to any of these, and he takes several measures step-by-step to show how, in practical and logical thinking, a mobile learning solution can drive any or all of these measures. He concludes by suggesting that if an organization is investing in mobile learning or any other type of learning, it needs to connect to these business measures. Otherwise, it shouldn’t be pursued. This dramatic call for accountability is not that unusual.

TABLE 1-1. High-Level Business Benefits From Mobile Learning

| Decreased Product Returns | Reduced Incidents |

| Increased Productivity | Decreased Defects |

| Increased Accuracy | Increased Shipments |

| Fewer Mistakes | On-Time Shipments |

| Reduced Rise | Decreased Cycle Time |

| Increased Sales | Less Downtime |

| Less Waste | Reduced Operating Cost |

| Fewer Accidents | Fewer Customer Complaints |

| Fewer Compliance Discrepancies | Reduced Response Time to Customers |

Source: Adapted from Udell, C. (2012). Learning Everywhere: How Mobile Content Strategies are Transforming Training. Nashville, TN: Rockbench Publishing (co-published with ASTD Press).

The Executive View

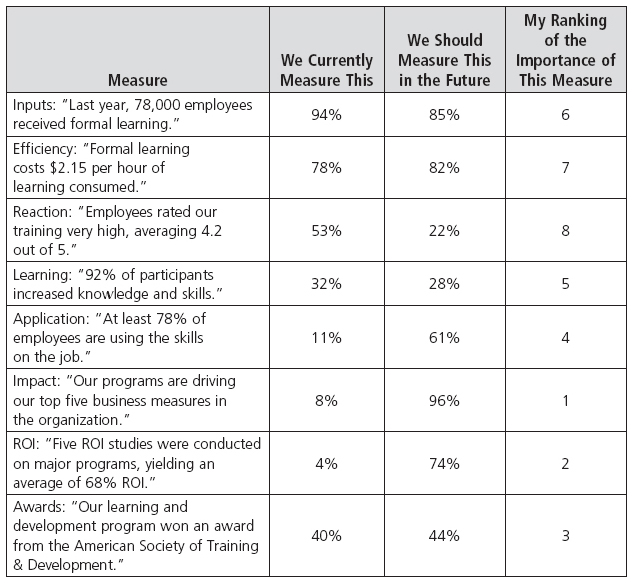

Those who fund budgets are adamant about seeing the connection. Yes, these executives realize that employees must learn through technology, using the devices, while being actively involved in the process and enrolled in the programs. But more importantly, they must use what they’ve learned and have the business impact. Top executives weighed in on this issue in an important study sponsored by ASTD (Measuring for Success: What CEOs Really Think About Learning Investment, 2010). In a study of large company CEOs, particularly the Fortune 500 group, the executives indicated the extent to which they see certain type of metrics connected to learning now, what they would like to see in the future, and the ranking of these measures. Table 1-2 shows the results.

Clearly, this table shows that regardless of what method of learning is used, executives want to see the business connection. In total, 96 percent of them want to see business impact, but only 8 percent see it now. Surprisingly, 74 percent would like to see the ROI on learning, and yet only 4 percent see it now. Even for application, the use of the learning on the job, 61 percent wanted to see this data, and only 11 percent see it now. Clearly, the measures that executives want to see are not being pursued to a significant degree by the learning and development team, regardless of whether learning is technology based or classroom based.

TABLE 1-2. Executive View of Learning Investments

Results Are Missing

Unfortunately, the majority of results presented in learning through technology case studies are devoid of measurements at the levels needed by executives. Only occasionally are application data presented, measuring what individuals do with what they learn, and rarely do they report a credible connection to the business. Even rarer is the ROI calculation. In a recent review of award-winning e-learning and mobile learning case studies published by several prestigious organizations, the following observations of results were noted.

• No study was evaluated at the ROI level where the monetary value of the impact was compared to the program’s cost to calculate the ROI. Only two or three were evaluated on the cost savings of technology-based learning compared to facilitator-led learning. This may not be a credible evaluation.

• The benefits and results sections of the studies mentioned ROI but didn’t present it. They used the concept of ROI to mean any value or benefit from the program. Mislabeling or misusing ROI creates some concerns among executives who are accustomed to seeing ROI calculated a very precise way from the finance and accounting team.

• Credible connections to the business were rare. Only one study attempted to show the impact of mobile learning using comparison groups. Even there, the details about how the groups were set up and the actual differences were left out. When the data are vague or missing, it raises a red flag.

• Many of the studies made the connection to the business based on anecdotal comments, often taken from very small samples. Sometimes comments were observations from people far removed from the actual application. For example, a corporate manager suggesting that e-learning is “making a difference in store performance.”

• Very few results were provided for application. Although they can be built in, they were rarely reported, usually listed as antidotal comments about the use of the content and the success they are having with its use.

• Learning was measured, but in less than half of the studies. Learning is at the heart of the process, yet it was left out of many of these studies.

• Reaction was typically not addressed in these studies. Reaction measures such as “relevant to my work,” “important to my success,” “I would recommend it to others,” and “I intend to use this” are very powerful predictors, but not measured very frequently in technology solutions.

Clearly, as this review of studies has shown, there is more talk than action when it comes to the value of technology-based learning. So the pressure is on for proponents of technology-based learning to show the value to funders and sponsors, and this accountability should include business impact and maybe even the ROI. Although business impact and ROI are critical for senior executives, they rarely make this level of analysis. Let’s explore why.

Reasons for Lack of Data

In our analysis of technology-based learning programs, several major barriers have emerged. These obstacles keep the proponents from developing metrics to the levels desired by executives. Here are eight of the most significant ones.

1. Fear of results. Although few will admit it, the number one barrier is that the individuals who design, develop, or own a particular program are concerned about evaluation at the business impact and ROI levels. They have a fear that if the results are not there, the program may be discontinued and it will affect their reputation and performance. They prefer not to know, instead of actually taking the time to make the connection. The fear can be reduced if process improvement is the goal—not performance evaluation for users, designers, developers, and owners.

2. This is not necessary. Some of the designers and developers are suggesting that investments in technology-based learning should be measured on the faith that it will make a difference. Though executives may want results at these levels, there is a concern that technology should not be subjected to that level of accountability. After all, technology is absolutely necessary in the situations outlined in the beginning of this chapter. Although the learning may have to be technology based, this doesn’t preclude it from also delivering results.

3. Measuring at this level is not planned. When capturing the business impact and developing the ROI, the process starts from the very beginning, at the conception of the project or program. The planning at this point helps facilitate the process and even drive the needed results. Unfortunately, evaluation is not given serious consideration until after the project is implemented—too late for an effective evaluation.

4. Measurement is too difficult. Some feel it is too difficult to capture the data or that it’s impossible to secure quality information. Data collection was not built into the process, so therefore it takes extra steps to find it. When it’s collected, it’s difficult to connect the business data to the program and convert to monetary value. The ROI seems to be too complicated to even think about. Using systematic, easy steps helps with this process. Technology proponents tackle some very difficult problems and create marvelous solutions requiring much more knowledge, expertise, and capability than the measurement side of the process. Measurement is easy and doesn’t demand high-level mathematics, knowledge of statistics, or expertise in finance and accounting.

5. Impact and ROI is too expensive. By the time the evaluation is considered, the investment in technology and development is high and designers are unwilling to invest in measurement. The perception is that this would be too expensive, adding cost to a budget that is already strained. In reality, the cost of evaluation is a very minute part of the cost of the project, often less than 1 percent of the total cost, for an ROI study.

6. Measurement is not the fun part of the process. Technology-based learning is amazing, awesome, and impressive. What can be accomplished is exciting for those involved and for those who use it. Gamification is taking hold. People love games. They’re fun. Measuring the application, impact, and ROI is not fun. Metrics could be made more interesting and fun at the same time using built-in tools and technology. Designers, developers, and owners need to step up to the responsibility to show the value of these processes.

7. Not knowing which programs to evaluate at this level. Some technology proponents think that if they go down the ROI path, executives will want to see the ROI in every project and program. In that case, the situation seems mind boggling and almost impossible. We agree. The challenge is to select particular projects or programs that will need to be evaluated at this level.

8. Not prepared for this. The preparation for designers, developers, implementers, owners, and project managers does not usually include courses in metrics, evaluation, and analytics. Fortunately, things are changing. These issues are now addressed in formal education. Even ROI Certification is available for technology-based learning applications.

Because these barriers are perceived to be real, they inhibit evaluation at the levels desired by executives. But they are myths for the most part. Yes, evaluation will take more time and there will be a need for more planning. But the step-by-step process is logical. Technology owners bear the responsibility to show the value of what they own. The appropriate level of evaluation is achievable within the budget and it is feasible to accomplish. This book shows how it’s done in simple, easy processes. The challenge is to take the initiative and be proactive—not wait for executives to force the issue. Owners and developers must build in accountability, measure successes, report results to the proper audiences, and make adjustments and improvements. This brings technology-based learning to the same level of accountability that IT faces in the implementation of its major systems and software packages. IT executives have to show the impact, and often the ROI, of those implementations. Technology-based learning should not escape this level of accountability.

FINAL THOUGHTS

![]()

This initial chapter covered the landscape of technology-based learning, revealing some of the trends and issues of this explosive phenomenon in the learning and development field. There is no doubt that learning through technology is the wave of the future. It has to be, with complex and large organizations and an ever increasing need for learning. In a society that is willing to take only small amounts of time for anything, learning through technology is just in time, just enough, and just for the user. However, it must be subjected to accountability guidelines. It must deliver value that is important to all groups, including those who fund it. Executives who fund large amounts of technology-based learning want to see the value of their programs and projects. Their definition of value is often application, impact, and ROI. The challenge is to move forward and accomplish this in the face of several barriers that can easily get in the way. The rest of the book will show how this is accomplished.