Chapter 2

The Mechanics of Merger Arbitrage

This chapter discusses the first three types of merger consideration and how arbitrageurs will set up an arbitrage trade and profit from it:

- Cash mergers

- Stock-for-stock mergers

- Mixed stock and cash mergers

Cash Mergers

The simplest form of merger is a cash merger. It is a transaction in which a buyer proposes to acquire the shares of a target firm for a cash payment.

We will look at a practical example to illustrate the analysis. An announcement for this type of merger is shown in Exhibit 2.1, which is the press release announcing the purchase of Autonomy Corporation, a U.K.-based infrastructure software firm, by Hewlett-Packard Co. It is typical of announcement of cash mergers.

The terminology used in mergers is quite straightforward: A buyer, HP in this case, proposes to acquire a target, Autonomy here, for a consideration of £25.50 per share. The difference between the consideration and the current stock price is called the spread. When the stock price is less than the merger consideration, the spread will be positive. Sometimes the stock price will rise above the merger consideration, and the spread can become negative. This happens occasionally when there is speculation that another buyer may enter the scene and pay a higher price.

In a cash merger, the buyer of the company will cash out the existing shareholders through a cash payment, in this case £25.50 per share. An arbitrageur will profit by acquiring the shares below the merger consideration and holding it until the closing, or alternatively selling earlier.

Arbitrageurs come across press releases as part of their daily routine search for newly announced mergers. This one was released on August 18, 2011, at 4:10 pm Eastern Standard Time, which was 9:10 pm British Summer Time, when markets both in Europe and the United States were closed. For regulatory reasons, companies announce significant events like mergers after the end of regular market hours or in the morning prior to the opening. This is meant to prevent abuse by investors with slightly better access to news. With the growing importance of after-hours trading and the availability of 24-hour trading of U.S. stocks through foreign exchanges, this restraint has already become somewhat pointless but is still considered best practice.

The first observation an arbitrageur will make is that the stock of Autonomy jumped immediately upon the announcement of the merger. As can be seen in Figure 2.1, Autonomy closed at £14.29 on August 18, the last day before the announcement of the merger. It opened at £25.27 on August 19, quickly peaked at £25.29, and moved down for the rest of the day to close at £24.52. Some unfortunate investors bought shares at the opening price, and because there must be a seller for every buyer, some lucky sellers parted with their investment at the high price for the day. An investor who wanted to enter into an arbitrage on this merger had a realistic chance of acquiring shares at the day's average price of £24.92. Volume that day was brisk: While it had averaged just under 1 million shares per day (precisely 0.97) over the prior month, it reached 48.6 million on August 19 and averaged 3.7 million per day over the next month. Therefore, the assumption that an arbitrageur could have obtained that day's average price is reasonable.

Figure 2.1 Stock Price of Autonomy before and after the Merger Announcement

A chart like that shown in Figure 2.1 is typical of stocks undergoing mergers. The buyout proposal is generally made at a premium to the stocks' most recent trading price. This leads to a jump in the target's stock price immediately following the proposal. As time passes by and the date of the closing approaches, the spread becomes narrower. This means that the stock price moves closer to the merger price. An idealized chart is shown in Figure 2.2, whereas Autonomy's actual chart is more typical of the behavior of most such stocks. Figure 2.1 also shows the FTSE index, the stock index considered a reference for the London market. Its axis has been scaled (right-hand side) to match the percentage change in Autonomy's stock price. If Autonomy and the FTSE have the same percentage change, then their respective lines will move by the same magnitude in the graphic. It can be seen that prior to the merger announcement, Autonomy's moves on a daily basis match those of the FTSE very closely. After the announcement on August 19, Autonomy and the index no longer move in tandem. This is a good visual illustration at the micro level of the low correlation that merger arbitrage has with the overall stock market. Fluctuations in the index do not impact Autonomy once it becomes the target of an acquisition.

Figure 2.2 Idealized Chart of Stock in a Cash Merger

In some instances, the buyout proposal is made at a discount to the most recent trading price. This rarely happens and is limited to small companies where the buyer is in a position to force the sale. It often leads to litigation and a subsequent increase in the consideration. A transaction at a discount to the last trading price is called a takeunder.

An arbitrageur who buys the stock on August 19 for £24.92 will receive £25.50 when the transaction closes. The gross profit for the capital gain on this arbitrage is £0.58 on £24.92, or 2.33 percent:

where

| is the gross return. | |

| is the cash consideration received in the merger. | |

| is the purchase price. |

This return will be achieved by the closing of the merger. A key component in investments is not just the return achieved but also the time needed. A more useful measure of return that makes comparisons easier is the annualized return achieved. The relevant time frame starts with the date on which the arbitrageur enters the position and ends with the date of the closing. The press release stated that the “acquisition of Autonomy is expected to be completed by the end of calendar 2011.” Therefore, the last day of the year, December 31, is used as a conservative estimate for the closing of the transaction. Pedantic arbitrageurs would choose December 30 instead because December 31 was a Saturday in 2011. As there is a large degree of uncertainty about when the transaction will actually close and the choice of the closing date is no more than an educated guess the difference between the two dates is not very meaningful. In practice, the companies will work very hard to close the transaction before the Christmas holiday, so that it is equally justifiable to work with a projected closing date of December 23rd. There are 126 days in the period until the anticipated closing to December 23rd. Two methods can be used to annualize the return: simple or compound interest.

Simple interest

-

2.2

where

is the annualized gross return.

is the number of days until closing.

Compound interest

-

2.3

where

is the annualized gross return.

is the number of days until closing.

Personal preference determines which method is used. Simple interest is useful if the returns are compared to money market yields that are also computed with the simple interest method, such as the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) or Treasury bills (T-bills). Compound interest is preferable if the result is used in further quantitative studies. If the returns are compared to bond yields, they should be adjusted for semiannual compounding used in bonds. It is an error encountered frequently, even in research by otherwise experienced analysts and academics, that yields calculated on different bases are compared with one another.

A projected annualized return of 6.74 percent is sufficient to make this investment highly desirable at a time when overnight LIBOR rates in Sterling were around 0.58 percent and the 10-year benchmark Gilt yielded around 2.6 percent.

It is helpful to look at the actual outcome of this merger arbitrage. The Autonomy acquisition closed earlier than an arbitrageur would have assumed: November 14, 2011. With this shorter 88-day time frame to closing, the realized annualized return was 9.65 percent and 10.01 percent for the simple and compound interest methods, respectively. Over the same period, the FTSE returned 10 percent, or an annualized 48.5 percent. However, this better short-term performance came at a price of a volatility that was also significantly higher: Autonomy's daily volatility was 3.4 percent, whereas that of the FTSE was 25 percent.

Autonomy was a non–dividend-paying company. In case a company does pay dividends, there is another source of income that the arbitrageur must factor into the return calculation. For an example, consider Australian bulk grain exporter GrainCorp Limited, which was acquired by Archer-Daniels-Midland Co. for A$2.8 billion. The per-share acquisition price was only A$12.20, but an additional A$1 was to be paid in dividends. Due to the large dividends to be received by shareholders, the stock traded above the A$12.20 level following the announcement of the merger. On April 30, 2013, four days after the announcement, an arbitrageur could have acquired GrainCorp for a volume weighted average price of $12.8239, with an expectation that the transaction would close by September 30, 2013, or within 157 days. A back-of-the-envelope calculation for the net return with dividends is to add the dividend to the merger consideration received. This gives an annualized return of 6.95 percent if the compound interest method is used:

where

| is the amount of the dividend received. |

A more accurate method is the calculation of the internal rate of return (IRR). Spreadsheets have built-in functions to calculate IRRs that require the user to enter each payment with the associated date, as shown in Figure 2.3. It is important to note that the dividends were spread over different payment dates. A first net dividend payment of A$0.25, consisting of a $0.20 interim dividend and a $0.05 special dividend, was to be paid on July 19. The dates of any future dividends were not yet known, Since Australian companies pay semiannual dividends, it is safe to assume that no dividend will be received during the 10-week period between July 19 and the closing on September 30. The prior final dividend was paid on December 17, 2012, so that the final dividend would probably also be paid in the middle of December should the merger not be completed by then. Since the arbitrageur is working for now with a closing date of September 30, it is assumed that the final dividend payment will be made simultaneously with the payment of the merger consideration on September 30.

Figure 2.3 IRR Calculation of Annualized Return in Excel

The resulting projected return is an annualized return of 7.21 percent, slightly higher than in the simplified calculation. The reason for the difference lies in the earlier receipt of the dividend cash flow in the IRR calculation.

The actual date of the dividend payment and its amount are not always known at the time of the announcement of a merger. In this case, the arbitrageur will make an educated guess for the next payment date based on the company's payment frequency and past dividend amounts. Care must be taken when foreign companies are listed in another country. For example, U.S. companies pay dividends with a quarterly frequency. However, U.K. companies listed in the United States and their ADRs pay semiannual dividends to all of their shareholders, even those who purchased the shares in the U.S. market. Similarly, Swiss companies pay only one dividend per year even when listed in the United States. Whenever the dividend information becomes known, such as the announcement of the dividend date or the exact amount, arbs must update their spreadsheets promptly.

Arbitrageurs must be aware of a few limitations of this approach:

- The returns calculated are projections that are highly dependent on the date of the closing of the merger. A delay can quickly lower the return on the investment.

- The projections say nothing about the path that the investment takes on its way to closing. Sometimes, following an initial spike after the merger announcement, a target company's stock weakens. An arbitrageur will then have to book a temporary loss on the investment. Of course, this marked-to-market loss will be reversed eventually when the merger closes. However, the projection cannot make a prediction on the trading dynamics of the stock between purchase and merger closing.

Stock-for-Stock Mergers

Stock-for-stock mergers are more complicated than cash mergers. In stock-for-stock mergers, a buyer proposes to acquire a target by paying in shares rather than cash. Sometimes the consideration paid can be a combination of stock and cash. That case is addressed later.

A good example of a stock-for-stock merger announcement is shown in Exhibit 2.2. It is the $4 billion acquisition of Australian gold miner CGI Mining Ltd by Canada's B2Gold Corp, announced in September 2012.

In this case, B2Gold is the buyer, CGA the target, and the per share consideration is no longer a fixed cash amount but a fixed number of B2Gold shares. Shareholders of CGA will receive 0.74 shares of B2Gold for each share of CGA that they hold. The number 0.74 is referred to as the exchange ratio or conversion factor.

The dollar amount of C$3.18 mentioned in the press release refers to the value of the merger on the day before the announcement. This amount is calculated simply by multiplying the closing price of B2Gold's stock of C$4.30 on September 18, the last trading day before the announcement, by the conversion factor of 0.74. It is not the value that shareholders will receive at the closing of the merger. The value will vary with the stock price of B2Gold. This distinction is important, because unlike in the case of a cash merger, arbitrageurs face an uncertain dollar value at the time of closing that will vary with B2Gold's stock price. Therefore, they cannot just buy the stock of the target CGA and wait for the merger to close.

The naive approach would be to purchase CGA stock and wait for the merger to consummate. The investor would receive 0.74 shares of B2Gold that it would then need to sell at the prevailing market price, which could be higher or lower. There is no arbitrage in such a transaction. Recall that one of the elements of the definition of arbitrage was that a purchase and sale occur simultaneously. Holding a stock and waiting to sell it for a higher price is speculation, not arbitrage.

Instead, arbitrageurs must lock in the value of the transaction through a short sale. For readers new to short sales, a brief explanation is given here. Additional aspects of short sales are discussed in Chapter 14.

One complication in the merger is that even though CGA Mining is an Australian company, it is dually listed in Canada and Australia. An arbitrageur must decide which of the two shares to purchase. A brief glance at the trading volume of the shares on the two exchanges shows that the vast majority of the trading volume occurs in the Canadian market. Another advantage of investing in the Canadian shares is that arbitrageurs do not have to deal with the unfavorable time zone during which the Australian market is open for trading. Executing both sides of the arbitrage simultaneously can be difficult for companies whose shares are listed on different continents and where opening hours overlap only briefly, if at all.

The stock prices of B2Gold and CGA are shown in Figure 2.4. It can be seen that CGA jumped on September 19, the day of the announcement, from a close of C$2.65 the prior day to an open of C$2.84, rose as high as C$2.95 during the day and closed at C$2.71. B2Gold had closed at C$4.30 before the announcement and fell to a closing price of C$3.79. Articles in the press often attribute such a drop of an acquirer's stock price to skepticism about the merger in the investor community. However, it will be seen that the drop is often the byproduct of arbitrage activity.

Figure 2.4 Stock Prices of B2Gold and CGA

For simplicity, it will be assumed that an arbitrageur enters the position on September 19 at the closing price. The arbitrageur will execute two transactions:

- Pay C$2.86 per share to buy 1,000 shares of CGA. This is the volume-weighted average price (VWAP) for the day, a realistic level at which investors could have bought CGA.

- Sell short 740 shares of B2Gold at C$3.95 per share, which is the VWAP for this stock for September 19.

It helps to examine the cash flows and stock holdings after these two trades. They can be found in Table 2.1. There is an expense of C$2,860 to acquire the shares of CGA, and proceeds from the short sale amount to C$2,923.

Table 2.1 Cash Flows in CGA/B2Gold Merger

| Stock Transaction | Cash Flow | |

| CGA | C$(2,860) | |

| B2Gold | C$ 2,923 | |

| Net | — | C$ 63 |

It can be seen that this transaction leaves the arbitrageur with a net cash inflow of C$63. At the closing of the merger, the 1,000 shares of CGA will be converted into 740 shares of B2Gold. The arbitrageur is then long 740 shares and at the same time short 740. The long position can then be used to deliver shares to the counterparty from which the short position was borrowed. Once the delivery has been completed the arbitrageur no longer has a position in stock, long, or short, but is left with a profit of C$63.

The example of 1,000 shares is useful for illustrative purposes. Rather than looking at the purchase of 1,000 shares, transactions should be calculated on a per-share basis. Each share of CGA is converted into 0.74 shares of B2Gold. For each share of CGA purchased, the arbitrageur must sell short 0.74 shares of B2Gold. By multiplying the exchange ratio with the stock price of B2Gold, it can be seen that per share of CGA an arbitrageur receives C$2.923 (0.74 × 3.95) from the short sale of B2Gold. The spread is hence C$0.063 per share of CGA.

The return calculation is simplified here in that no dividends need to be taken into account. Neither of the two companies has ever paid any dividends, and there was no reason to believe that this would change prior to the closing of the merger.

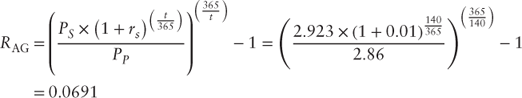

where

| is the proceeds received from the short sale, per share of target stock. | |

| is the price at which the acquirer is sold short. | |

| is the exchange ratio. |

The gross return on this arbitrage is 2.2 percent.

Calculation of the annualized return works as in the example of a cash merger. Only the calculation of compound returns is shown here; simple interest can be calculated analogously. Unlike in the prior examples, the arbitrageur cannot find a direct reference to the closing date in the press release. “The merger will be implemented by way of a Scheme of Arrangement under the Australian Corporations Act 2001” gives a valuable hint. As I will explain later, a scheme of arrangement follows a well-defined timetable. A five-month time frame is a reasonable estimate. If we assume a closing date of February 28, 2013, then there are 162 days from September 19, the day the position was entered.

Compound interest

-

2.6

The expected annualized return at the time of entering the position is 5.0 percent. The actual closing of this merger occurred on January 18, 2013, so the actual return on this arbitrage was an annualized 6.9 percent over 121 days.

One of the advantages of stock-for-stock mergers is the simultaneous holding of a long and a short position. Because of the upcoming merger, the two stocks are highly correlated, so that an increase in CGA's stock price is accompanied by an offsetting increase in B2Gold's. If the two stocks were no longer to move in parallel, the spread would change, and the annualized return available to arbitrageurs would either compress or expand.

However, as the fluctuations in the two stocks mostly cancel out due to the short position in B2Gold, the net result for the arbitrageur is a much smoother ride than what an index investor experiences. The evolution of the spread of the CGA/B2Gold merger is shown in Figure 2.5. In the case of a cash transaction, the spread depends on only one variable. In a stock-for-stock merger, it depends on two stock prices. The spread does trend toward zero over time. The spread is not very smooth on an absolute basis. But compared to the gyrations in the index over the same time, the volatility is much lower.

Figure 2.5 Evolution of the CGA/B2Gold Spread

It is clear that short sales from arbitrage activity can lead to significant selling pressure on the stock of a buyer after the announcement of a stock-for-stock merger. Often analysts and journalists attribute the drop of a buyer's stock after a merger announcement to fundamental reasons, such as the prospect for the merged entity. One account of the trading activity following the announcement of the merger of Trane Inc. with Ingersoll-Rand is shown in Exhibit 2.3. Ingersoll-Rand fell over 11 percent following the announcement of the merger. The fundamental reasoning behind this merger appeared solid. Some reports suggested that the combination of the two firms created the number-two air-conditioning company in the United States. The long-term prospects of Ingersoll-Rand clearly were not bad and would not have justified an 11 percent drop. It can be explained only by arbitrage activity. Experienced investment bankers warn company management during merger negotiations of the risk to their stock price and suggest structures with a cash component to a stock-for-stock merger in order to reduce short selling.

Merger arbitrage is attractive to many investors as a portfolio diversifier because of its long/short components. It is assumed that these positions immunize the portfolio against fluctuations in the overall stock market and leave only uncorrelated event risk to the investor, and therefore, the portfolio is market neutral. This argument is revisited in more detail in Chapter 3. Nevertheless, at this point, a short discussion of one of the pitfalls of long/short positions is necessary. A constant percentage spread can lead to dollar paper losses in an extreme bull market, if both the long and the short position increase, but the percentage spread remains constant. Table 2.2 illustrates the problem of a hypothetical increase of CGA and B2Gold when the percentage spread remains constant throughout the increase. The losses discussed here are temporary only and will eventually be recovered once the merger closes.

Table 2.2 Losses Suffered at a Constant Percentage Spread in a Rising Market

| CGA | B2Gold | Value at Exchange Ratio | Spread ($) | Spread (%) | Loss ($) | |

| Market Increase | 2.86 | 3.95 | 2.923 | 0.063 | 2.20% | 0 |

| 5% | 3.00 | 4.15 | 3.069 | 0.066 | 2.20% | 0.003 |

| 10% | 3.15 | 4.35 | 3.215 | 0.069 | 2.20% | 0.006 |

| 15% | 3.29 | 4.54 | 3.361 | 0.072 | 2.20% | 0.009 |

| 20% | 3.43 | 4.74 | 3.508 | 0.076 | 2.20% | 0.013 |

| 25% | 3.58 | 4.94 | 3.654 | 0.079 | 2.20% | 0.016 |

| 30% | 3.72 | 5.14 | 3.800 | 0.082 | 2.20% | 0.019 |

| 35% | 3.86 | 5.33 | 3.946 | 0.085 | 2.20% | 0.022 |

| 40% | 4.00 | 5.53 | 4.092 | 0.088 | 2.20% | 0.025 |

| 45% | 4.15 | 5.73 | 4.238 | 0.091 | 2.20% | 0.028 |

| 50% | 4.29 | 5.93 | 4.385 | 0.095 | 2.20% | 0.031 |

| 55% | 4.43 | 6.12 | 4.531 | 0.098 | 2.20% | 0.035 |

| 60% | 4.58 | 6.32 | 4.677 | 0.101 | 2.20% | 0.038 |

| 65% | 4.72 | 6.52 | 4.823 | 0.104 | 2.20% | 0.041 |

| 70% | 4.86 | 6.72 | 4.969 | 0.107 | 2.20% | 0.044 |

| 75% | 5.01 | 6.91 | 5.115 | 0.110 | 2.20% | 0.047 |

| 80% | 5.15 | 7.11 | 5.261 | 0.113 | 2.20% | 0.050 |

| 85% | 5.29 | 7.31 | 5.408 | 0.117 | 2.20% | 0.054 |

| 90% | 5.43 | 7.51 | 5.554 | 0.120 | 2.20% | 0.057 |

| 95% | 5.58 | 7.70 | 5.700 | 0.123 | 2.20% | 0.060 |

| 100% | 5.72 | 7.90 | 5.846 | 0.126 | 2.20% | 0.063 |

Table 2.2 starts in the first row with the actual spread of 2.20 percent at prices of C$2.86 and C$3.95 for CGA and B2Gold, respectively. It shows the profit and loss (P&L) relative to a position entered at the baseline of C$2.86 and C$3.95. If both CGA and B2Gold rise and the percentage spread remains constant, then the spread expressed in dollars must rise (2.2 percent of $5.72 is more than 2.2 percent of $2.86). The simulated price rise in Table 1.3 shows that a spread of $0.063 will widen to $0.126 per share if CGA were to double in value to $5.72 per share. Although B2Gold's stock appreciates by the same percentage as CGA, the difference in dollar terms increases. At $5.72 per share, the arbitrageur's portfolio would record a loss of $0.063 per CGA share (last column).

This scenario does not imply inefficiency in the market. If the hypothetical increase in spreads were to occur on the same day as the position was entered, the annualized return would be unchanged, because the percentage spread is the same whether CGA trades at $5.72 or at $2.86.

It is clear that these losses are only paper losses that are temporary. As long as the merger eventually closes, the arbitrageur will realize a gain of $0.063. Only those who panic and close their position early will suffer a real loss. The arbitrageur is short 0.74 shares of B2Gold for every long position of CGA, and the cash changed hands already when the trade was made. Therefore, the eventual profit is certain as long as the merger closes. In the meantime, however, the account will show a loss.

Whether or not an arbitrageur wants to hedge against paper losses is a matter of personal preference. Any hedging transactions will entail costs and will reduce the return of the arbitrage. Because the spread eventually will be recovered, it makes little sense to hedge against transitory marked-to-market losses.

Now what would happen if stock prices were to fall? It can be extrapolated from this discussion that in the case of a fall in stock prices, the dollar spread will tighten, and the arbitrageur will record a gain even though the percentage spread and the annualized return would remain unchanged.

Sometimes shareholders hold a number of target shares that does not get converted to a round number of buyer shares. For example, a holder of 110 shares of CGA would receive 81.4 shares of B2Gold. However, the fractional 0.4 shares cannot be traded or issued because corporations have whole shares only. (Note that mutual funds are different, even though they are also organized as corporations.) Therefore, companies will liquidate fractional shares and issue only full shares. The investor in our example would receive 81 shares of B2Gold and a cash payment for the value of the fractional 0.4 shares. The cash payment depends on the share price of B2Gold at the time of the closing of the merger.

In addition to earning the spread, a stock-for-stock merger has another source of income. When arbitrageurs short a stock, they receive the proceeds of the short sale. In the example from Table 2.1, the arbitrageur received C$2,923 from the short sale of B2Gold. These funds are on deposit at the brokerage firm that executed the short sale. Arbitrageurs can negotiate to receive interest on this deposit. This is easier said than done. In the author's experience, most retail brokerage firms do not pay interest on the proceeds of short sales. At the time of writing, one retail brokerage firm advertised that it had paid interest on balances of short proceeds in excess of $100,000. Institutional investors are better off. They are always offered interest on the proceeds. This is referred to as short rebate in industry parlance.

The example of the CGA/B2Gold merger can illustrate the effect of the short rebate on merger arbitrage returns. Assume that the short rebate is 1 percent. At the time of writing, in a period of historically low interest rates, this would be a high rate. In normal interest rate environments, short rebates are higher and match LIBOR rates. In fact, it is quite normal for rates for short rebates to be below interest rates. In fact, the spread between short rebates and margin rates charged customers who borrow to buy stock is an important source of revenue for brokerage firms. The interest earned on the $2,923 over the 140-day period until the closing of the merger would have been

This would increase the merger profit from $63 to $74.21—an increase of almost 18 percent. For simplicity, simple interest is used in this calculation. Most brokers pay interest monthly, so monthly compounding should be used.

The annualized spread increases by the amount earned on the short rebate:

where ![]() represents the interest paid on the short rebate.

represents the interest paid on the short rebate.

As discussed in Chapter 3, returns on merger arbitrage tend to be correlated with interest rates as a result of the impact that short rebates have on spreads.

The CGA/B2Gold merger was easy to analyze because neither stock pays any dividends. Stocks paying dividends can be tricky to handle when sold short, because the short seller must pay the dividend on the stock. The long position will generate a dividend; the short position will cost a dividend. A crude calculation to determine the net effect of dividends on the annualized spread is to subtract the dividend yield of the short position from the dividend yield of the long position, and add the result to the annualized return of the merger arbitrage. However, this method can give incorrect results, especially for mergers with a short horizon to closing. The method can be used as a first approximation, but arbitrageurs always must consider the actual dividend dates and dividend amounts.

The gross return in the presence of dividends is calculated for a long/short merger arbitrage in this way:

where

| are the total dividends to be paid on the short sale. | |

| are the total dividends to be received on the purchased (long) stock. |

Mixed Cash/Stock Mergers

Many buyers want to limit dilution in the acquisition of a target company or have access only to an amount of cash insufficient to purchase the target entirely for cash. They structure the acquisition of a target for a dollar amount plus shares, or they offer target shareholders the option to choose between cash and stock, typically with a forced proration.

In the former case, every shareholder of the target company is treated equally. Exhibit 2.4 shows the announcement of the merger of Alterra Capital Holdings Ltd. with Markel Corp, announced in December 2012. This merger was mentioned briefly earlier to illustrate the effect that arbitrage-related short selling can have on a company's stock price immediately following the announcement of a merger.

Alterra's shareholders will receive $10 plus 0.04315 share of Markel. Alterra's shares traded on December 19 at a VWAP of $28.58, whereas those of Markel traded at a VWAP of $444.97. An arbitrageur entering a position at these prices would make a gross return of 2.17 percent:

where

| as before. | |

| is the cash component received in the merger. |

This gross return should be annualized by one of the methods explained earlier. An arbitrageur would also have to factor in the receipt of at least one additional dividend of $0.16 / share, which, based on Alterra's dividend history, would be paid in the middle of February 2013. A second dividend may be paid in the middle of May, if the merger has not closed by then.

A different incarnation of mixed cash/stock transactions does not specify a set dollar amount to be received per share but instead sets a fraction of the total consideration that will be paid in cash. Frequently used ratios are 50/50 cash/stock, 40/60, or 20/80.

The acquisition by Vulcan Materials Company of Sunoco Inc. by Energy Transfer Partners, LP had the frequently used ratio of 50 percent cash and 50 percent stock. The press release is shown in Exhibit 2.5.

Mixed transactions with election rights can be difficult to calculate because they require some guesswork. Arbitrageurs are used to making assumptions, as we have seen in the estimation of closing dates and now again when dealing with cash/stock proration ratios. Shareholders can choose to receive either cash or stock. Arbitrageurs and some shareholders will pick the option that is worth the most. In this transaction, if the value of Energy Transfer Partners shares to be received is above $50.00 at the time of the merger, profit-maximizing shareholders will want to receive shares. If the value of these shares is less than $50, shareholders will prefer $50 in cash instead of the less valuable shares. In either case, no shareholder will accept a blend of shares and stock. The buyer would either have to pay all stock or all cash, which is not what it intended to do. For this reason, these transactions have a proration provision, so that the buyer of the firm can make the blended cash/stock payment of 50 percent stock and 50 percent cash. However, not all shareholders will seek to be paid in cash when the shares are below $50. Some shareholders fail to make a selection and will be allocated the less valuable consideration by default. Many long-term shareholders will select shares even when the cash payment is more valuable because they intend to continue to hold the shares. Strategic investors or managers will hold on to their shares. Some asset allocators may find it easier to roll their shares into the buyer's stock than reinvest themselves. Finally, the most important group selecting stock rather than cash are long-term holders who have significant appreciation in their holdings of target stock. They would be faced with an immediate tax bill if they realized a gain in the merger. By selecting stock, they can defer realization of a taxable gain into the future. Because all of these investors have a preference for stock even if the cash component is worth more at the time of the merger, slightly more cash will be paid to shareholders who select cash than if proration were applied at the stated ratio.

In the case of Sunoco, 73.92 percent of shareholders elected to receive cash, 4.25 percent elected all stock, 2.61 percent requested to receive the 50/50 proration, and the remaining 19.22 percent did not make a selection. Shareholders who did not make a selection also received the 50/50 mix. Out of luck were shareholders who elected to receive all cash: Due to proration, they received $26.47 in cash and 0.49373 shares of Energy Transfer Partners. This shows that aiming for one of the extremes—all cash or all stock—can be a risky undertaking. An arbitrageur who hoped for an all-cash allocation would have ended up with almost half of the position exposed to the market—not quite an arbitrage. Most of the time, it is optimal to target the prorated allocation. With some experience and a study of the shareholder base, it is possible to make a rough estimate of the final proration.

Arbitrageurs must use experience and guesswork to determine the ratio that is most likely to apply. In the next discussion, it is assumed for simplicity that the ratio of cash/stock that the arbitrageur will receive is that of the stated proration factor.

To calculate the gross return,

where

| is the ratio of stock to be received. | |

| is the ratio of cash to be received (obviously, |

|

| is the proceeds received from the short sale, per share of target stock. | |

| As before, |

|

This gross return can be annualized by analogy with the previous examples.

Mergers with Collars

The CGA/B2Gold merger discussed above had a fixed exchange ratio of 0.74. This exposes both CGA and B2Gold to a certain market risk: If the value of B2Gold's stock increases significantly, then the 0.74 shares that CGA shareholders will receive for each share will also increase in value. In this case, the value of the transaction will be much higher than $4 billion. While CGA shareholders will be happy with this outcome, the investors in B2Gold will wonder whether they could have acquired CGA by issuing fewer shares and suffering less dilution. Conversely, if B2Gold's stock falls, then CGA's shareholders will receive less valuable shares for each B2Gold share. They would have been better off with a higher exchange ratio.

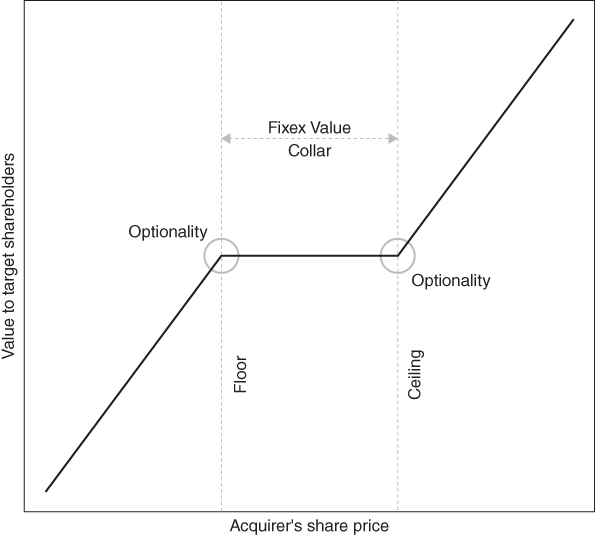

For this reason, many merger agreements include provisions to fix the value of stock received by the target company's shareholders at a set dollar amount or at a fixed exchange ratio. The exchange ratio is adjusted as a function of the share price of the acquirer. Two reference prices are determined.

Two types of collars are common:

- Fixed-value collars. Target shareholders will receive a set dollar value's worth of shares of the acquirer as long as the acquirer's share price is within a certain collar. This collar is buyer-friendly. The exchange ratio can change within the collar range. This type of collar is so common that the term fixed value is often dropped. References to a generic “collar” relate to fixed-value collars.

- Fixed-share collars. A set number of shares is given to the target shareholders as long as the acquirer's share price is within a certain range. If the acquirer's share price rises above the maximum, the exchange ratio declines. This collar is seller-friendly. The exchange ratio is fixed within the collar range.

The November 2012 acquisition of investment bank KBW, Inc., by Stifel Financial Corp. contained a fixed-value collar, shown in the press release in Exhibit 2.6.

In this acquisition, KBW shareholders will receive a package worth $17.50 as long as the share price of Stifel is between $29 and $35. In this case, they will receive $10 in cash and $7.50 worth of Stifel stock. For example, if the price of Stifel is $31, they will receive $10 plus 0.2419 shares of Stifel. The ratio of 0.2419 is calculated by dividing $7.50 by $31. If the price of Stifel stock falls below $29, then the ratio will be fixed at 0.2586, so if Stifel stock is worth only $25, then the value received by KBW shareholders will be only $16.47 ($10 cash, plus Stifel stock worth $25 × 0.2586). Below the lower collar boundary, KBW shareholders will participate in any depreciation of Stifel shares, as they would if the ratio had been fixed, and will receive less value than $17.50. Similarly, for a share price above the upper boundary of the collar, the value received will exceed $17.50. For example, for a price of Stifel shares of $40, KBW shareholders will receive a package worth $18.57 ($10 cash, plus Stifel stock worth $40 × 0.2143). Certainty as to the value exists only within the collar.

Readers are fortunate that the press release in Exhibit 2.6 is very explicit about the boundary prices of the collar. Exhibit 2.7 shows an example of a merger agreement that forces arbitrageurs to do a little extra math. An arbitrageur has to calculate the reference values for the collar from the information in the merger agreement. The value is fixed at $18.06 per share in the collar, and the exchange ratio can fluctuate between 0.4509 and 0.4650. The two reference prices are calculated as

This is an uncharacteristically narrow collar. As long as Health Care REIT's stock price remains between $38.84 and $40.05, Windrose's shareholder will receive $18.06 worth of Health Care REIT's stock. The range for this collar is less than 5 percent of the buyer's stock price. Typical are ranges of 10 or 15 percent. It can be seen from chart in Figure 2.6 that Health Care REIT was fluctuating quite wildly during the merger period and exceeded the upper limit of the collar by the time of the closing on December 20, 2006.

Figure 2.6 Fluctuation of Health Care REIT's Stock Price Prior to the Merger

Arbitrageurs must hedge mergers with collars dynamically. If the merger is hedged with a static ratio and the stock price of the acquirer moves, the arbitrageur will incur a loss. For example, 10 days after the announcement, Stifel traded below $29 and an arbitrageur investing at that time would have hedged with a ratio of 0.2586. By January 2013 and until the closing, Stifel stock traded above $35. Therefore, at the time of the closing, the arbitrageur would have received only 0.2143 shares. The arbitrageur would have had an excess short position of 0.0443 shares. With Stifel worth $38.75 on the day of the closing of the merger, an arbitrageur would have had to purchase these extra short shares at a cost of $1.717 per share of KBW. This would have reduced the profitability of the arbitrage by about 10 percent, and led to a loss. Conversely, if an arbitrageur enters into a position when it trades at the upper bound of the collar and the stock price declines, there will be an insufficient number of shares sold short. This underhedging results in the short position not generating enough return to offset losses on the long position of the arbitrage. The correct way to hedge a collar is dynamically, in the same way that an option collar is hedged by an option market maker.

In the case of the Windrose/Health Care REIT merger, the collar is very tight and the hedge ratio does not change very much. It would be possible to enter an arbitrage position with a static hedge ratio and assume the modest risk that the position needs to be adjusted once the exact conversion ratio is known. An arbitrageur will weigh the potential transaction costs of such a strategy against the spread that can be earned. However, such a narrow collar is an exception rather than the norm, so this question hardly ever arises.

A more accurate method for hedging transactions with collars is delta hedging. Both discontinuities in the payoff diagram of collars lead to optionality (see Figure 2.7). The discontinuity to the left of a fixed-value collar resembles the payoff diagram of a short put position, whereas the discontinuity to the right resembles a long call position. In a delta-neutral hedge, the arbitrageur calculates the sum of the deltas of these two options and shorts the number of shares given by that net delta. A drawback of delta-neutral hedging is that it requires constant readjustment with fluctuations in the stock price and as time passes. However, for wide collars with exchange ratios that change significantly, delta-neutral hedging is the best method to hedge. For further details on the concept of delta hedging, the reader should consult texts dealing with options.

Figure 2.7 Optionality in Mergers with a Fixed-Value Collar

Fixed share collars are less common than fixed-value collars. One recent example of this rare structure is shown in Exhibit 2.8. It is the September 2010 acquisition of AirTran Holdings, Inc. by Southwest Airlines Co.

This collar is straightforward. If Southwest Airlines' share price falls below $10.90, shareholders of AirTran will receive more shares so that the value they receive remains $3.50. This is a very risky transaction to enter for a buyer, and probably one of the reasons for its rarity. If Southwest Airlines' share price were to suffer a sudden sharp drop, it will have to issue more shares in the merger. The additional issuance dilutes existing shareholders and leads to a drop in the share price with the issuance of even more shares. It risks triggering a downward death spiral in the share price. In order to minimize the risk of unanticipated dilution, the merger agreement allows Southwest Airlines to deliver additional cash in lieu of stock. As discussed earlier, arbitrage activity always exerts some selling pressure on an acquirer's stock, so that the possibility of this effect should not be ignored. Only buyers who acquire target companies that are small relative to their own size should use fixed-share collars, because the dilution would remain insignificant even for a sharp drop in share prices, and no death spiral would be triggered. If Southwest Airlines accepted a fixed-share collar, it must have been very confident that its share price would remain strong.

The number of shares to be issued as long as Southwest Airlines' share price is in the collar is fixed at a ratio of 0.321 of Southwest shares for each share of Airtran owner. For prices above the upper and below the lower bounds of the collar, it is the dollar value of the consideration that is fixed rather than the number of shares, so that the exchange ratio varies.

This transaction can be hedged only through a delta-neutral hedging strategy.

Figure 2.8 shows the implied options in a fixed-rate collar. The combination of a long call with a low strike price and a short call with a higher strike price yields such a payoff diagram. This combination is also known as call spread or bull spread. An arbitrageur who wants to hedge a fixed-rate collar needs to calculate the delta for each option, sum the deltas, and then short the net delta in the form of shares of the target firm.

Figure 2.8 Optionality in Mergers with a Fixed-Share Collar