Chapter 4

Incorporating Risk into the Arbitrage Decision

So far, all arbitrages were analyzed under the assumption that the merger would close. Unfortunately, life is not that easy for an arbitrageur. A small number of mergers are not completed. The usual outcome of non-completion is a drop in the share price of the target firm and steep losses for arbitrageurs. However, in rare instances, the collapse of a merger can lead to an increase in a stock's price. This happens very rarely. One of the few cases that I have seen was the attempted acquisition of Unisource Energy by Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. Even in this case, the increase did not happen instantly after the announcement that the Arizona Corporation Commission voted to reject the buyout. On the day of the announcement, Unisource fell (see Figure 4.1). However, over the next month, Unisource rose and eventually exceeded the price that shareholders would have received in the merger. This is the one exception that proves the rule that collapsing mergers lead to a loss.

Figure 4.1 Stock Price of Unisource after the Collapse of the Merger

In other instances, shareholders are relieved when an acquisition fails and the share price appreciates instantaneously.

Most acquisitions are made at a significant premium to the most recent market price. Partly this is justified by the need to motivate current holders to forgo future upside, for example because buyers anticipate cost savings that they can share with the selling investors. At a minimum, this premium should be given back when a merger is canceled. Bigger losses are often possible because the composition of a company's shareholder base changes during the merger process. The interaction between long-term holders and arbitrageurs is an important factor that determines the extent of a drop. Long-term holders often sell their holdings, and arbitrageurs acquire these shares. If the merger collapses, arbitrageurs have little interest or incentive to hold the position much longer. They want to take their loss and move on the next merger. Therefore, significant involvement by merger arbitrageurs in a collapsing transaction will exacerbate losses.

In finance, the analysis of losses separates into two dimensions:

- The probability that a loss will happen.

- The extent of the losses. Credit analysts refer to this as “severity” or “loss given default.”

Readers may be familiar with this distinction from credit analysts. As we shall see later, there are many analogies between merger arbitrage and credit management. Like credit analysts, arbitrageurs estimate the probability of a merger collapsing and the severity of the loss separately. The two are combined to give the expected loss:

where

| L | is the severity of the loss. |

| Pr(L) | is the probability of suffering a loss. |

| E(L) | is the expected value of the loss. |

The expected loss is also called a probability-weighted loss. It represents the loss that an arbitrageur expects to suffer on average if positions in a large number of identical mergers were taken.

The probability of suffering a loss is just the inverse of the probability of the merger closing. In terms of the probability of success, this can be rewritten as

Probability of Closing

The vast majority of merger transactions are completed without problems. It is my experience that even among the transactions that do run into problems, the eventual completion rate is high.

Academic research has been trying for the past 25 years to examine the probability of successful completion of mergers. Many of these studies are directly related to the returns that can be achieved through merger arbitrage. These studies have identified a number of factors that drive the completion of a merger:

- Hostile transactions generally have a lower probability of success than friendly transactions. This comes as no surprise to anyone reading the newspaper headlines.

- One recurring factor that increases the likelihood of a successful merger closing is the market size of the target. However, there is no agreement on the direction in which this variable influences the outcome. Early studies show that larger transactions are less likely to close than smaller ones.1 More recent studies2 indicate that large transactions are more likely to fail than smaller ones. This discrepancy between the conclusions of these studies may simply be a reflection of different market environments.

- The impact of the bid premium is similarly uncertain for the probability of completion. While it is clear that a larger bid premium will lead to a larger loss if a merger collapses, it is less intuitive to see why a large premium could impact the probability of the merger closing.

- Tender offers are less likely to close than mergers.3 Tender offers typically require a participation of 90 percent, whereas mergers can be voted with a 50 or 662/3 percent majority, so that the threshold for the latter is easier to reach. In addition, this also could be another manifestation of the size effect, because cash tender offers are smaller on average than stock-for-stock mergers.

- Index membership increases success. One study4 finds that mergers are more likely to be completed if the buyer is a member of the S&P 500. A likely explanation is that reputational risk matters more for large, well-known companies.

- The percentage of stock owned by the acquirer affects the outcome. If the acquirer owns a larger percentage of the target firm prior to the announcement, the merger is more likely to close.

Ben Branch and Taewon Yang5 find that 89 percent of all mergers were completed in the period from 1991 to 2000. They find that the type of payment impacts the probability: Collar mergers have the highest success rate with 93 percent, whereas stock-for-stock mergers without collar provisions only come to 88 percent. Cash tender offers are the least successful types of mergers with a completion rate of only 87 percent. In their study regarding mergers of S&P 500 members, Fich and Stefanescu6 find failure rates shown in Table 4.1.

Table 4.1 Failure Rates of Mergers According to Fich and Stefanescu

| Cash Merger | Stock-for-Stock Merger | |

| In S&P | 7.45% | 10.29% |

| Not in S&P | 27% | 25.7% |

Based on analysis by Eliezer M. Fich and Irina Stefanescu, “Expanding the Limits of Merger Arbitrage,” University of North Carolina Working Paper, May 18, 2003.

As most of these studies rely heavily on data from the 1990s, a model with more recent merger data was built.7 For convenience, only cash mergers were considered. Information about mergers for the three years from January 1, 2002, until December 31, 2004, retrieved from Bloomberg consists of 797 transactions announced in that period, of which 648 had closed. After eliminating mergers of questionable data quality, the ultimate data set consisted of 528 cash mergers. No minimum transaction size was imposed, and therefore, the distribution of this dataset is weighted heavily toward small mergers of less than $50 million. Many studies consider only “investable” mergers above $50 million. In this model, 468 mergers closed and 60 were terminated, giving a failure rate of 11.5 percent. This is in line with the results of the studies just mentioned.

The probability of success of a merger can be estimated through logistic regressions. This type of regression relates a binary variable, such as the merger closes (1) or fails (0), to continuous variable, such as the size of the firm. Several models have been developed in the literature. Based on the Bloomberg data set of 528 cash mergers, the author developed a logit estimator of the probability of success:

where

| DealSize | represents the size of the acquisition in $billions. |

| Owned | is the percentage of the target firm owned by the acquirer prior to the announcement of the transaction, represented as a number between 0 and 1. |

The sparse nature of the model illustrates the problem in the estimation of models that can be used in merger arbitrage. Despite the wealth of studies on the completion of mergers, it is difficult to build statistical models to calculate probabilities accurately. Factors determining the likelihood of successful completion vary from transaction to transaction. In statisticians' language, mergers have too many degrees of freedom. The first hurdle to overcome is data collection. Unlike financial variables used in most models, the information relevant to merger arbitrage is only partially quantitative. Some of the factors that are not amenable to incorporation into models are subtleties in the wording of merger agreements, such as material adverse change clauses; in a contested merger, the skill of an acquirer in building alliances; and in the case of transactions challenged on antitrust grounds, the ability of companies to divest divisions and thereby become compliant with antitrust regulations. At best, a statistical model can be used as a starting point, and its results then must be adjusted subjectively.

Arbitrageurs should also bear in mind that the definition of what constitutes a failed merger can vary depending on the context in which one looks at the data. For example, an arbitrageur would consider the bidding war between HP and Dell over 3PAR (Chapter 5) a single merger that was highly profitable. An investment banker, however, would consider this as two transactions of which one failed: one merger between 3PAR and HP, and another between Dell and 3PAR. From the investment banker's point of view, this definition makes sense, as one of the banks would not earn a success fee because its client did not acquire the target. So the arbitrageur will see a 100 percent success rate, while the investment banker will see a 50 percent failure rate. Similarly, if one were to look only at bids, one would note that a total of seven bids for 3PAR were made, of which naturally only the last one was successful. Therefore, arbitrageurs need to be careful and understand exactly the definition underlying statements that claim certain failure or completion rates in mergers and acquisitions.

The remainder of this section discusses a number of factors that frequently lead to the cancellation of mergers. It should be remembered that often the confluence of several problems is necessary to lead to the cancellation of a merger. Buyers have different reasons to try to void a merger from target companies. Separation is more likely to happen when both buyer and target have good reasons to walk away from the merger.

The most important pitfalls that can lead to the cancellation of a merger are discussed in future chapters in great detail. The next sections give an overview of factors that arbitrageurs should be mindful of.

Reverse Merger Arbitrage

A variation of merger arbitrage is to set up the arbitrage in a way that it benefits from a deal collapse when an arbitrageur believes that the probability of such a collapse is very large. In a survey8 it was found that 95.24 percent of arbitrageurs engage in such a strategy, which is also referred to as Chinesing a merger.

This strategy can be successful not only when a merger collapses, but also when the time frame of a merger is extended. Even if the annualized spread stays constant in an extension, the dollar spread must widen and an arbitrageur will benefit from this widening.

Reverse merger arbitrage is important, as it keeps spreads at levels that reflect risk even if many arbitrageurs pursue an arbitrage strategy and substantial inflows of capital come into merger arbitrage funds. However, as the study by Rohani and Wanzelius discussed in Chapter 3 illustrates it is not easy to generate consistent positive returns with a reverse merger strategy.

Inability to Obtain Financing

In cash transactions, the ability of the buyer to obtain financing is one of the key determinants of a successful completion. This is of particular concern for highly leveraged transactions, such as those involving private equity funds as buyers. Financing is discussed in more detail in Chapter 7.

Changes in Business Conditions

Market, sector, and company risk are not normally associated with market-neutral investment strategies such as merger arbitrage. For merger arbitrage, event risk is the principal risk faced by arbitrageurs, namely the risk that the transaction will not occur. However, it would be naive to assume that none of the risks associated with traditional investment styles apply to arbitrage. These traditional forms of investment risk are second-order effects:

- The first-order risk is the event risk, the risk that the transaction fails.

- Market, sector, and company risk are second-order risks that can contribute to event risk.

Event risk is not completely independent of market movements. For large drops in the stock market, the risk of failure increases if the acquirer thinks it overpaid. For large increases in the stock price, shareholders may vote against the deal if they think they are not receiving a high enough price.

A significant deterioration in business climate is referred to as a material adverse change (MAC) in legal terms. Whether a buyer can walk away from a merger or not depends on the exact provisions of the merger agreement. MAC clauses have become more restrictive over time, and it is becoming increasingly difficult for buyers to invoke them. Doing so will inevitably lead to litigation, which has a negative effect on the share prices of the buyer and the target. The current status of MAC jurisprudence is driven by the IBP/Tyson Food decision in 2001.9 Tyson Foods had entered into a merger agreement to acquire IBP for $30 per share after winning a bidding war with Smithfield Foods but tried to cancel the acquisition when IBP reported poor results for the fourth quarter of 2000 as a result of harsh winter conditions. Tyson claimed that IBP's business had suffered a material adverse change. The judge in the case ruled that one bad quarter does not constitute a material adverse change and that IBP's business would have to be affected permanently in order to constitute MAC.

IBP was awarded “specific performance” by the court. This means that Tyson was forced to implement the merger agreement and complete the acquisition. It was the best outcome that IBP shareholders could have hoped for, and the merger closed in the middle of 2001.

MAC clauses and specific performance were tested in court during the financial crisis of 2008–2009. The most notorious incident was the failure of the acquisition of shoe retailer Genesco by its competitor Finish Line, a highly leveraged transaction. Superficially, Genesco suffered a material adverse change when its quarterly earnings declined, probably in relation to changes in consumer spending as the housing crisis unfolded. Finish Line claimed a material adverse change and sought to discharge its obligation to acquire Genesco by suing in Tennessee. From an arbitrageur's point of view, this was a challenge as no material adverse change case had ever been tried in that state. Although most courts habitually look to Delaware for guidance, judges will first take their own state's traditions into account. The Genesco case was complicated further when a parallel lawsuit was filed by Finish Line's banker that alleged fraud by Genesco. It claimed that Genesco had withheld critical financial information from the lender. This lawsuit was eventually dismissed—however, the bank that had filed it gained a few months in critical times and thus avoided taking potential writedowns worth several billion dollars on the high-yield debt that it had committed to providing. In the Tennessee action the judge ruled that although Genesco had suffered a material adverse change, this was excluded from the merger agreement and Finish Line was required to proceed with the purchase.

The ultimate outcome was a settlement between all parties. Although Genesco did not get acquired and arbitrageurs who held on to the position suffered a permanent loss, shareholders overall did well as Genesco was awarded equity in Finish Line. Effectively, the target ended up owning a slice of the buyer—a highly unusual outcome in a merger, to say the least.

Unfortunately, the remedy of specific performance is not available to shareholders in all states. While Delaware courts can impose specific performance, New York courts will not do so. Instead, they will force the buyer, should it lose the case, to pay monetary damages to the target rather than complete the merger. Although these damages will increase the value of the target, it is uncertain whether this will be sufficient to offset losses suffered by target's shareholders.

Today, lawyers write MAC clauses to exclude certain events that affect the economy in general but do not affect the target firm disproportionately. As a result, it is difficult for an acquirer who experiences buyers' remorse to back out of a transaction solely on the basis of MAC. Other loopholes must be invoked instead.

In the United Kingdom, MAC clauses can be a condition on which an offer is conditional. The main difference to the United States is that no exceptions to a material adverse change are allowed. As a result, they are very similar from one merger to another. A key ruling by the Panel on the question of MAC clauses came in the year 2001 when WPP had tried to acquire Tempus Group but attempted to cancel the merger due to the economic slowdown following the September 11 attacks and the associated deterioration in the advertising industry. The Panel ruled that

… meeting this test requires an adverse change of very considerable significance striking at the heart of the purpose of the transaction in question, analogous … to something that would justify frustration of a legal contract.

Specifically, the decline in advertising had to be distinguishable from the overall economic slowdown, which was not the case. In 2004, the Panel clarified its stance on the “frustration” of contract, whose standard is in line with general contract law. Since then, “frustration” is not necessarily required, but the standard applied to a MAC should be very high.

Public Intervention

Fortunately for arbitrageurs, politicians and the general public rarely show much interest in merger activity. Most concerns that arise are related to monopoly pricing power and affect antitrust issues. In some instances, however, public opposition to mergers falls outside of the narrow scope of an antitrust review.

However, in recent years cross-border mergers have become politicized. The acquisition by Chinese buyers in particular has attracted unwelcome political and media attention.

Within the U.S. one type of transaction particularly susceptible to political intervention is utility mergers. The long time period required to close such a merger is partly a reflection of the involvement of multiple state regulators. However, the number of regulators involved does not yet explain the low success rate of such mergers. After all, bank mergers also often involve several states and nevertheless have a high completion rate. Instead, the monopoly pricing power for the indispensable services provide by the utility triggers added interest by state regulators, the general public, and hence also politicians.

The federal government tends to take a hands-off approach to mergers with the exception of some high-profile areas (media, airlines, national security), so that the field of government interference is left wide open to state regulators. States always get involved in mergers of public utilities and sometimes in mergers of state-chartered banks. Utilities are a particular minefield because politicians are sensitive to allegations that any future price increases in rates are due to the state's failure to block a merger, potentially ending the careers of many local politicians.

In Europe, many large-scale mergers face popular uproar, and some aspect of a transaction is frequently scandalized. However, trade union representatives frequently have participated in the approval of a merger through their board representatives. This tends to assuage the public outrage.

Public intervention has become increasingly a problem in recent years, even in areas that have little exposure to national security. For example, in 2013 the Australian government blocked the proposed acquisition of bulk grain exporter GrainCorp by Archer Daniels Midland of the United States. Clearly, grain exports have no national security implications. However, the Australian government had made this merger an electoral issue during the election campaign a few months earlier in order to win the support of the farming lobby. While blocking this transaction had no military or other security implications, Australian Treasurer Joe Hockey of the ruling Nationals party stressed the “national interest.” The interests of the farming lobby cost shareholders a 22 percent drop in the share price on the day of the deal's collapse.

At times, intervention of politicians can assume farcical traits. After the 2014 announcement of a merger between Burger King and Tim Horton's of Canada, concerns arose over potential intervention of Canadian politicians who played on fears that their voters' favorite breakfast restaurant might be taken over by a U.S. chain that was controlled by Brazilian investors.

Relative Size of Buyer and Target

A merger is more likely to close if the buyer is much larger in size than the target. This is discussed in more detail in later.

Antitrust Problems

Antitrust problems are primarily concerns for strategic mergers but may become more prevalent in leveraged buyouts as large private equity firms acquire an increasingly large share of businesses. Antitrust issues are discussed in Chapter 8.

Shareholder Opposition

It happens frequently that long-term shareholders of a target company oppose a merger as providing too little value.

Similarly, shareholders of a buyer may also oppose an acquisition if they feel that the company overpaid.

Successful shareholder opposition is relatively rare, as it can be difficult to oppose a transaction if the premium paid relative to the last trading price is high. Most shareholders will take the certain money rather than live with the uncertainty of having the firm continue to be run by managers who may not have added much value. The lack of value addition is often the principal reason why a company becomes a takeover target in the first place.

Shareholder opposition is often a fruitless exercise, but it can wreak havoc on an arbitrageur's position. It takes a very well organized shareholder campaign to derail a merger. The typical reasoning of a shareholder is the argument that the company is worth more than what shareholders will receive in the merger, and so the firm should be sold to another buyer at a higher price. However, absent other buyers with a compelling higher offer, other shareholders have no incentive to follow this reasoning. In fact, once the merger was announced, the shareholder base has begun to change: Long-term shareholders sell their shares to arbitrageurs, who provide those shareholders with the liquidity they need. The arbitrageurs, in turn, are interested in a prompt closing of the merger rather than a lengthy search process. Even worse for an arbitrageur is a collapse of the deal without a competing higher offer; this situation leaves the arbitrageur open to market risk. In a stock-for-stock merger, this event can lead to the worst-case scenario where the target drops and the acquirer rises in a short squeeze due to the sudden simultaneous unwinding of arbitrage positions. The mere threat of a cancellation of a merger is often sufficient to induce arbitrageurs to reduce their exposure to the deal, which will lead to a widening of the spread and a mark-to-market loss for existing arbitrage positions. If a shareholder wants to mount a successful campaign to undo a merger, it must be done in a way that comforts arbitrageurs that they will not sit on a losing position at risk of market movements if the deal collapses.

It is easier for shareholders to oppose mergers than tender offers. A merger has a long time frame, giving activists a better opportunity to convince shareholders to vote against. In a tender offer, with a much shorter time frame, shareholders may have tendered their shares already by the time they receive word of opposition. In addition, they will get the consideration much sooner from the tender offer than any better deal in the future. Each shareholder faces a prisoner's dilemma: If all shareholders oppose the transaction, they may eventually be better off. However, a shareholder not tendering must wait until the completion of the second step, the short-form merger, to get paid. Because most investors, professional or retail, have high subjective discount rates, the immediate payoff in a tender offer is much more attractive than the same consideration after the second step or even hope for a better transaction down the road. Two transactions illustrate the difference.

In recent years, numerous examples of shareholder opposition to mergers could be witnessed. One of the most prominent cases was the failed attempt by shareholder activist Carl Icahn to block the $16 billion buyout of struggling computer manufacturer Dell Inc. by its founder Michael Dell and private equity firm Silver Lake. Several investors were reported to consider the initial bid of $13.65 in early February 2013 as being too low. Southeastern Asset Management subsequently disclosed an 8.5 percent stake and announced its intention to vote against the merger. T Rowe Price, a large institutional holder, also opposed the acquisition. About one month after the announcement of the acquisition, Carl Icahn announced a 6 percent ownership stake and advocated a leveraged recapitalization in lieu of the acquisition. Under his proposal, Dell would have paid a special dividend of $12 per share and would have remained a public company. Subsequently, he proposed to acquire the firm for $14 in cash. Eventually, Michael Dell and the Silver Lake increased the bid to $13.65 in cash plus a dividend of $0.13. Although Icahn threatened to perfect appraisal rights—an avenue he did not pursue in the end— the transaction closed on the revised terms after about 7 months.

Icahn's agitation at Dell resembles the fight several years earlier in the acquisition of VistaCare, where healthcare hedge fund Accipiter Capital Management opposed the acquisition by VistaCare's competitor Odyssey HealthCare. Accipiter encouraged shareholders not to tender their shares and to seek appraisal rights. Accipiter had a solid case to make: VistaCare was in the middle of a turnaround that was beginning to show fruit. This is an uncommon event in itself. Many companies appear to drift from one turnaround to another without ever having any success. Margins were beginning to improve. In addition, the earnings yield of the firm was depressed artificially because the $8.60 stock had a cash balance of $1.40 per share. VistaCare's gross margins were almost half those of Odyssey. Nevertheless, 84 percent of shareholders tendered their shares in Odyssey's offer during the first offer period, which lasted almost one month. Odyssey extended the tender period for four more days, after which it had obtained 94 percent of all shares and was able to close the merger.

Even long proxy fights are insufficient for shareholders to block some mergers. When SCPIE, a California medical insurance firm, was acquired by The Doctors' Company, long-term shareholder Stilwell attempted to block this transaction in favor of a higher bid by one of SCPIE's competitors, American Physicians Capital (ACAP). ACAP had also been bidding to acquire SCPIE and offered $28 in stock, whereas The Doctors Company, as a private firm, offered $28 in cash. Much of the public disagreement between Stilwell and the SCPIE's board concerns the question whether ACAP's bid was better or not. The board points to the certain value of cash and the absence of a firm bid from ACAP. However, ACAP was prevented from making a bid under a standstill agreement that it had previously signed in order to conduct due diligence. Unfortunately, Stilwell's many shareholder communications never made clear where the problem was, and SCPIE was eventually sold to The Doctors' Company.

Outside the United States, shareholder activism is less frequent and, when it occurs, less vocal. One problem is, particularly in Europe, that few channels exist for activists to communicate with shareholders. Unlike in the United States, depositories may not always be obligated to forward communications from activists to beneficial holders of shares. Moreover, many companies have anchor investors, a few large institutional holders. These key investors often determine the direction of a company and the outcome of shareholder votes. Therefore, activists opposed to a sale may not feel a need to go public and may simply discuss strategy with the core investors directly. The result is that shareholder opposition may occur, but if it does it remains behind closed doors, making it difficult for arbitrageurs who rely on publicly available information to take investment decisions.

Nevertheless, a few examples exist where public opposition to takeovers has had some success. One is the purchase of Danish food additive manufacturer Danisco A/S by E. I. du Pont de Nemours in 2011. The tender offer was opposed by the association of Danish retail investors as insufficient. However, in a pattern by now familiar to the reader, du Pont increased its tender price marginally from DKK 665 to DKK 700 and thereby obtained 92 percent of the shares, enough to complete the takeover. It was the rare absence of anchor investors combined with the widespread and fragmented ownership, atypical in Europe, that allowed the opposition to prevail. Nevertheless, there are a few instances in Europe where fragmented ownership can help activists pushing for an increase.

An even more favorable outcome for shareholders was the 2013–2015 acquisition of Club Mediterranee SA by a consortium that consisted of management and Fosun International with the backing of private equity firm AXA Private Equity. The initial 17-euro bid for a minimum of 50.01 percent of the shares was not met with enthusiasm by shareholders even after the price was increased to €17.50. The investor group had commitments of 24.87 percent of all outstanding shares. At that point, an investor filed a court action challenging the independence of the valuation expert who had pronounced the acquisition price as fair. After a seven-month delay, as the court decision approached, investors began to announce publicly that they would not tender. One group, Strategic Holdings of Italian financier and turnaround expert Andrea Bonomi, hoped to enter “constructive talks with the management of Club Med to the benefit of the company” and began to build a stake: 5 percent initially, followed quickly by a disclosure of a 10.07 percent position with an announcement that it sought to acquire 15 to 20 percent. The situation for the company became so desperate that it had to remind one of its Italian investors, Edizione, controlled by the Benetton family, of its irrevocable commitment to tender, and filed a lawsuit to compel Edizione to make good on its irrevocable commitment and tender its 2.2 percent stake. The Paris commercial court dismissed this lawsuit. In June 2014, Bonomi announced a €21 acquisition proposal through another of his holdings, Investindustrial Development SA. Club Med's management promptly recommended this offer. Ten weeks later, Fosun returned with a slightly higher €21 bid, which then became the recommended offer, only to be outbid two months later by Bonomi with a €23 bid. Fosun promptly countered with €23.50, followed by another counterbid for €24. The winner of the auction was Fosun with €24.60. Shareholders realized an upside of almost 50 percent as a result of persistent opposition.

The acquisition of Pinnacle by Quest Resources is one of the rare examples where shareholder activism can succeed in derailing a merger. However, it succeeded only against a backdrop of unhappy investors. The effects of this merger gone bad are discussed later in this chapter.

Management Opposition

Hostile merger transactions are hostile by definition because the management of the target company is opposed to the merger. The nature of hostile transactions has changed significantly in the last decade.

Hostile mergers became a widespread phenomenon in the 1980s when corporate raiders sought to undo the effects of the conglomerate boom of the preceding decade. At the time, it was the raiders themselves who sought to acquire a company against the wishes of management. Managers of the target firms frequently were opposed to these buyouts because they would have lost their lucrative jobs. Shareholders, however, would have benefited from a sale of the company at a premium. One of the effects of management opposition was the justification of stock options by the buyout argument: If managers will gain wealth from a premium offered for shares by a buyer, their interests are more aligned with those of shareholders. An analogous argument can be made to justify golden parachutes: They compensate managers for the loss of their employment and make them less likely to oppose transactions that are favorable for shareholders.

Today, buyouts have changed; raiders rarely acquire firms anymore. Modern raiders are activist shareholders who agitate to get a company to sell itself, but the activists are not normally the ones who want to buy the firm.

An interesting and ultimately successful attempt to block a sale of itself was implemented by Sovereign Bancorp. Hedge fund Relational Investors had agitated to get Sovereign to sell itself. An opportunity to frustrate shareholders' push for a sale came in 2005, when Sovereign's management convinced Spanish bank Groupo Santander to acquire 19.8 percent of Sovereign through the issue of new shares and used the proceeds from the investment to purchase Independence Community Bank. Santander was seen as a management-friendly shareholder that was unlikely to sell out to any potential acquirer. In the words of the chief executive officer of Ryan Beck & Co., the firm that advised Sovereign: “Obviously, some shareholders don't like the Santander transaction, because it effectively means Sovereign won't be selling out in the short term.”10 Santander took on the role of a “white knight” typical of takeover defenses (see Chapter 8). Unlike in most such scenarios, however, Sovereign continued to exist as an independent bank. Usually a white knight takes complete control of the target. Therefore, the Santander/Sovereign merger stands out as a particularly shareholder-unfriendly management coup. Santander acquired the remainder of Sovereign during the banking crisis of 2008 at a much-reduced price compared to the value of Sovereign in 2005.

Due Diligence and Fraud

In rare instances, fraud is discovered after the signing of a merger agreement. Typically, fraud is a good enough reason to call off a deal.

After the signing of the merger agreement between Enron and Dynegy, it became known during Dynegy's due diligence process that Enron had engaged in a number of fraudulent activities. Readers will be familiar with the Enron saga given the press coverage it received at the time. The attempt by Dynegy to acquire Enron was only one short episode in the collapse. Dynegy had speculated that Enron would not collapse and that it might be able to acquire a valuable business that had been battered excessively. Therefore, Dynegy bid $9.5 billion in cash and stock for Enron. Dynegy had completed due diligence prior to signing the merger agreement but decided to conduct additional due diligence after the announcement of the transaction. Enron's situation continued to deteriorate, and Dynegy attempted to renegotiate the price. Eventually, the true state of Enron's business began to emerge, and credit agencies downgraded Enron, thereby triggering immediate repayment of much of its debt. Dynegy used this to call a “material adverse effect” and exited the merger agreement. The spread on this transaction had been unusually wide, which could have been an indication either that few in the market believed that the transaction was likely to be completed or, more likely, that the downside risk in the event of a collapse of the deal was a complete loss on the long position in Enron. It turned out that the latter was the case for any arbitrageur who attempted to profit from this transaction.

As an aside, Dynegy had provided Enron with emergency funding in the amount of $1.5 billion to prevent an immediate cash crunch. Fortunately, Dynegy had this loan secured by pipeline assets, which it recovered in the bankruptcy. It is common to see emergency funding for troubled businesses by acquirers as soon as a merger is announced. Absent fraud as in Enron, these transactions tend to be very likely to be completed, because a collapse of the target can make it impossible for the acquirer to retrieve assets that secure the funding. In fact, the loan can even be subordinated to prior debt under certain circumstances during bankruptcy. Partly for this reason, Dynegy settled by paying Enron $25 million after lengthy litigation over the pipeline assets.

Chinese companies are at particular risk of being impacted by fraud risk. This is discussed in Chapter 5.

Breakup Fees

Merger agreements contain breakup fees that the target company has to pay the buyer if it wants to cancel the merger. Less common are reverse-breakup fees, which the buyer has to pay the target company if it decides not to proceed with the transaction. Two types of breakup fees can be distinguished:

- Target breakup fees. These are the fees that the target firm must pay to the buyer if it cancels the merger. Triggers for the payment of breakup fees can be a negative shareholder vote, a change of mind by the board of directors, or the acceptance of a better proposal from another buyer. Generally, when the term breakup fee is used generically without further qualification, it refers to target breakup fees.

- Buyer breakup fees, more commonly known as reverse breakup fees. These fees are less common and are paid by the acquirer if it changes its mind. Reasons could be the unavailability of financing or negative shareholder votes.

The rationale behind break fees is the idea that a buyer has expended some effort into investigating the target firm, which it does not want to go to waste. However, an equally valid argument can be made that in the normal course of business not every initiative can be completed successfully, and M&A activity is no different than failed product releases or other mishaps.

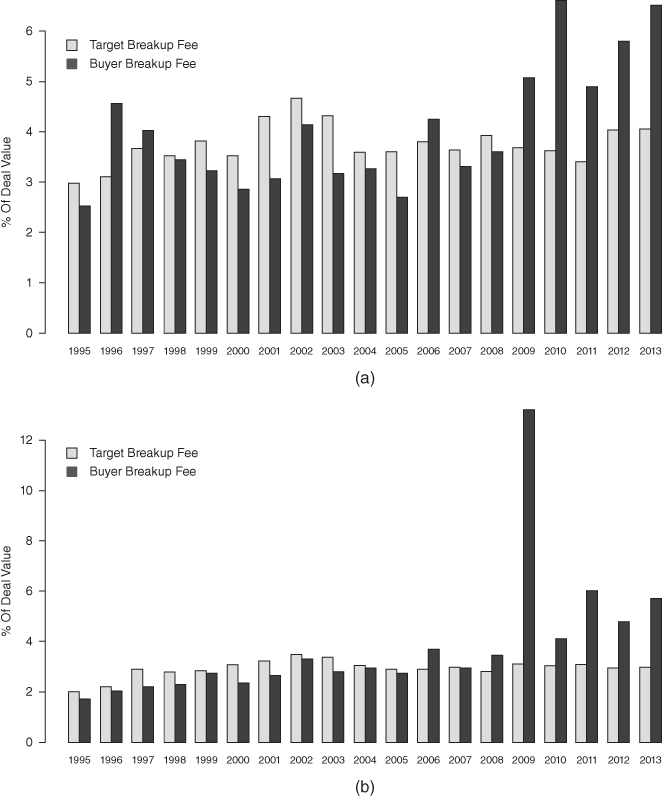

The extent to which breakup fees are allowed varies between jurisdictions. In the U.S. typical values for breakup fees are between 3 and 7 percent of the value of the merger. For smaller transactions, breakup fees as a larger percentage of the deal value are the rule. Figure 4.2 shows average target and buyer breakup fees for mergers of different sizes across all transactions, including those that have no breakup fees. However, when only transactions with breakup fees are considered, smaller transactions indeed have higher breakup fees as a percentage of the transaction value, as can be seen in Figure 4.3. The prevalence of breakup fees has increased over the last decade. By the middle of 2013, over 90 percent of all announced mergers had target breakup fees. For smaller transactions of less than $500 million equity value, almost one-third had buyer breakup fees, whereas they were present in more than half of all larger mergers (see Figure 4.4).

Figure 4.2 Typical Breakup Fees for Targets of Different Sizes across All Transactions

Figure 4.3 Typical Breakup Fees for Targets of Different Sizes Only for Transactions That Have Breakup Fees

Figure 4.4 Percentage of Transactions with Breakup Fees. (a) $50–500 Million. (b) >$500 Million

Arbitrageurs must read the merger agreement carefully to understand the circumstances under which breakup fees are payable. In some instances, staggered breakup fees are imposed, so that a higher or lower amount has to be paid depending on the reason for the cancellation of the merger. Breakup fees sometimes carry other monikers, such as in the case of the failed acquisition of movie and music distributor Image Entertainment by producer and financier David Bergstein. In this buyout, the buyer breakup fee was referred to as a business interruption fee. Breakup fees are generally not payable when a merger agreement is terminated due to a material adverse effect. Any other exceptions are spelled out in the merger agreement.

Breakup fees make the consummation of a merger more likely. A drawback is that if another buyer wanted to make a bid for the target firm, it would incur the breakup fee as a cost. Although the breakup fee is first an obligation of the target firm, no firm will enter into a new agreement unless the other buyer is willing to shoulder the fee. Otherwise, in a worst-case scenario, the second merger could collapse, and the target firm may find itself without a merger but with the obligation to pay the breakup fee.

During the financial crisis of 2007–2008, a number of leveraged acquisitions by private equity funds were canceled. Transactions involving private equity firms normally have not had reverse breakup fees in the past. One well-known case is that of the acquisition of student loan provider Sallie Mae by private equity firm J. C. Flowers. Sallie Mae was facing potential changes to its regulatory environment. When credit markets worsened and it became more difficult for J. C. Flowers to borrow the funds needed to complete the acquisition, the government adopted simultaneously regulatory changes that were different from those proposed at the time of the signing of the agreement. J. C. Flowers sought to cancel the agreement under its MAC clause. Sallie Mae argued that no material adverse change had taken place and sued J. C. Flowers for the breakup fee: $900 million. Sallie Mae had to drop the lawsuit against Flowers when it needed funding for its business and the lenders made settlement of the litigation a condition to providing the loans. If this breakup fee had been paid, it would have set a record unlikely to be overtaken for quite some time.

As Figure 4.4 demonstrates, the episode of 2007–2008 represents a turning point after which buyer breakup fees became much more prevalent.

The data in the Mergerstat database show the impact of breakup fees on the likelihood of the closing of a merger very clearly. For mergers above $500 million, completed deals have breakup fees that are higher than those of canceled mergers. Buyer breakup fees have significantly lower averages of 3.6 percent for all deals compared to 2.6 percent for canceled deals (see Table 4.2 (a) and (b)). The data suggest that breakup fees do indeed act as a deterrent to deal cancellations.

Table 4.2 (a) Average Breakup Fees for Completed and Canceled U.S. Mergers with an Announcement Value between $50 and $500 Million

| Target Breakup Fees | Buyer Breakup Fees | |||

| Industry | All Deals (%) | Canceled Deals (%) | All Deals (%) | Canceled Deals (%) |

| Commercial Services | 3.8 | 3.1 | 4.6 | 4.1 |

| Communications | 2.7 | 2.6 | 3.1 | n/a |

| Consumer Durables | 3.4 | 2.9 | 7.5 | 2.2 |

| Consumer Non-Durables | 3.2 | 1.8 | 4.0 | n/a |

| Consumer Services | 3.2 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 3.1 |

| Distribution Services | 3.9 | 2.2 | 3.5 | 5.0 |

| Electronic Technology | 4.3 | 4.7 | 4.7 | 4.9 |

| Energy Minerals | 3.1 | 2.0 | 3.5 | 3.8 |

| Finance | 4.0 | 4.2 | 3.1 | 3.5 |

| Health Services | 3.9 | 3.8 | 5.6 | 1.5 |

| Health Technology | 4.0 | 4.4 | 4.6 | 9.4 |

| Industrial Services | 3.5 | 1.9 | 3.3 | 1.5 |

| Miscellaneous | 3.0 | 3.1 | n/a | n/a |

| Non-Energy Minerals | 3.6 | 2.8 | 2.5 | 2.7 |

| Process Industries | 2.9 | 1.7 | 3.3 | 1.8 |

| Producer Manufacturing | 3.6 | 3.1 | 3.8 | n/a |

| Retail Trade | 3.4 | 3.1 | 5.4 | 3.2 |

| Technology Services | 4.6 | 4.9 | 4.4 | 5.4 |

| Transportation | 3.4 | 6.3 | 3.8 | 10.2 |

| Utilities | 3.5 | 10.4 | 2.3 | n/a |

| Overall Average | 3.6 | 3.6 | 4 | 4.2 |

Source: Analysis based on Mergerstat data.

Table 4.2 (b) Average Breakup Fees for Completed and Canceled U.S. Mergers with an Announcement Value of More Than $500 Million

| Target Breakup Fees | Buyer Breakup Fees | |||

| Industry | All Deals (%) | Canceled Deals (%) | All Deals (%) | Canceled Deals (%) |

| Commercial Services | 3.2 | 2.2 | 8.3 | 1.5 |

| Communications | 3.5 | n/a | 3.2 | n/a |

| Consumer Durables | 3.5 | 2.4 | 4.5 | 3.7 |

| Consumer Non-Durables | 2.6 | 1.9 | 2.6 | 2.0 |

| Consumer Services | 2.9 | 1.9 | 3.2 | 3.7 |

| Distribution Services | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 1.8 |

| Electronic Technology | 2.6 | 3.9 | 2.9 | 2.2 |

| Energy Minerals | 3.3 | 2.7 | 3.4 | 2.5 |

| Finance | 1.8 | 4.0 | 2.6 | 3.7 |

| Health Services | 2.6 | 2.7 | 4.1 | 2.0 |

| Health Technology | 2.7 | 3.1 | 2.7 | 2.2 |

| Industrial Services | 2.6 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 3.4 |

| Non-Energy Minerals | 2.7 | 2.5 | 2.9 | 2.5 |

| Process Industries | 2.8 | 2.1 | 3.7 | 2.2 |

| Producer Manufacturing | 2.5 | 2.2 | 4.3 | n/a |

| Retail Trade | 3.4 | 2.1 | 4.2 | 3.2 |

| Technology Services | 2.6 | 3.3 | 3.2 | 3.6 |

| Transportation | 2.7 | 1.6 | 2.9 | 1.1 |

| Utilities | 3.0 | 1.7 | 4.7 | 2.7 |

| Overall Average | 2.8 | 2.6 | 3.6 | 2.6 |

Source: Analysis based on Mergerstat data.

A large difference exists in average breakup fees between completed and canceled transactions. It is due mainly to the absence of breakup fees in many canceled deals. For those deals that have target breakup fees, their averages are almost identical for successful and canceled deals: 3.55 percent versus 3.56 percent in the case of target breakup fees for small and 2.79 versus 2.56 percent for large transactions. However, the difference becomes significant for buyer breakup fees in larger mergers, where the different amounts to a whole percentage point: 3.6 versus 2.58 percent. This finding suggests that the presence of breakup fees is a much stronger indicator of management determination to close the deal than their higher or lower level. Managers of target firms should insist in their negotiations on a buyer breakup fee or face a higher chance of a deal collapse.

Over the last two decades, average breakup fees have increased significantly, as the evolution of average target and buyer breakup fees depicted in Figure 4.6 demonstrates. The increase of buyer breakup fees is particularly striking. Much of the increase is driven by the larger percentage of mergers that contain breakup fee clauses, as can be seen in Figure 4.5. It shows that target boards are seeking some recourse from the buyer in case the deal falls through.

Figure 4.5 Prevalence of Breakup Fees. Percentage of Transactions That Contain Breakup Fees for (a) U.S. Mergers with an Announcement Value between $50 and $500 Million (b) Announcement Value of More Than $500 Million

Figure 4.6 Evolution of Breakup Fees for (a) U.S. Mergers with an Announcement Value between $50 and $500 Million (b) Announcement Value of More Than $500 Million

Termination fees in Canadian mergers have levels that are generally comparable to those in the United States. However, a smaller proportion of merger agreements contain such provisions. Only about half of Canadian mergers have target break fees, and fewer than a quarter have reverse termination fees (Figure 4.7).

Figure 4.7 Canadian Breakup Fees. (a) Prevalence of Breakup Fees (b) Level of Breakup Fees

The U.K. Takeover Code has some of the strictest limitations on the use of break fees, as they are called in the United Kingdom. The U.K. Takeover Code will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 8. For now, it is sufficient to state that U.K.-listed companies are subject to the provision of the Takeover Code. Until the reform of the Takeover Code effective in the year 2011, U.K. mergers target break fees occurred regularly, albeit in a smaller percentage of mergers than in the United States or Canada. With the 2011 reform, break fees were banned under Rule 21.2(a) in general, but predictably, the Panel will permit exceptions. A break fee of up to 1 percent is allowed in contested situations where the board is looking for competing buyers (a white knight), or after the completion of a formal sales process with the preferred bidder. The intent is to give comfort to a white knight to enter into a bidding contest. For this reason, break fees are sometimes referred to as inducement fees. The break in prevalence of break fees following the reform of the Takeover Code is visible clearly in Figure 4.8. The level of break fees in the United Kingdom is shown in Figure 4.8 (a), and the percentage of transactions that are subject to break fee in Figure 4.8 (b). In contrast to the situation in North America, several years had not a single U.K. merger with buyer break fees.

Figure 4.8 U.K. Breakup Fees: (a) Prevalence of Breakup Fees (b) Level of Breakup Fees

The wording of the break fee agreement in the offer by Shell for Cove Energy plc is shown in Exhibit 4.1 and demonstrates the contested circumstances under which the agreement was concluded and due to which a break fee can be permitted. Cove was subject to a hostile bid by Thailand's PTTEP and approached Shell as a white knight. The break fee was an inducement to Shell to assume this role. However, eventually Cove was acquired by PTTEP.

In continental Europe, the availability of break fees varies from country to country. No public company mergers in France, Austria, and Germany have break fees. In the Netherlands, Belgium, Italy, Switzerland, Luxembourg, and Spain, public company mergers have occurred with break fees. However, given the low deal volume in these countries and the rare occurrence of break fees, there is little point in further analysis.

Although at least buyer breakup fees appear to provide a strong incentive for closing a merger transaction, a case can be made that they are overrated. Their principal benefit is to the buyer, who gets a nice payoff when a higher bidder comes along and acquires the target. In the rare cases where buyers must pay breakup fees, lengthy litigation is begun, and buyers try any means available to get out of their payment obligation. The collapse of the recent private equity–buyout boom provides many examples of busted mergers where private equity firms escaped the payment of breakup fees that could have had crippling effects on their businesses. Private equity firm J.C. Flowers was potentially on the hook for a record $900 million breakup fee after it pulled out of the acquisition of student loan provider Sallie Mae. Even though part of the breakup fee was to have been paid by the banks that had committed to providing the financing for the buyout, it would have affected Flowers's ability to raise funds for future deals among investors if such a large sum had been used to pay for the nonconsummation of a buyout rather than actually invested. Sallie Mae, Flowers, and the banks settled the litigation within only three months through a deal in which J.P. Morgan, Bank of America, and a syndicate of other banks provided Sallie Mae with $31 billion of financing.

A similar arrangement helped Goldman Sachs Group and Kohlberg Kravis Roberts avoid paying a $225 million breakup fee when they pulled out of the $8 billion acquisition of Harman International Industries. They acquired $400 million in convertible bonds from Harman instead, paying 1.25 percent interest. The proceeds of the bond were used to repurchase shares. Harman would have been better off receiving the breakup fee rather than a loan that must be paid back in one way or another—either in cash or by dilution of existing shareholders. Harman could have used the breakup fee to repurchase stock and then borrowed another $175 million to retire additional stock. It would have left its balance sheet in much better shape with less debt. It is unclear why the board accepted a transaction that was so unfavorable to shareholders.

Large breakup fees have become a feature of many transactions where boards take their fiduciary duties seriously. A merger agreement with its exclusivity provisions, MAC clauses, and break fees can give the acquirer a free option. If everything goes smoothly, they acquire the target; when there is a problem, they can walk away from the target. Boards have come to recognize this dilemma and demand acquirer break fees more aggressively than in the past. In some mergers reverse breakup fees have recently reached levels unimaginable just a few years ago. For example, in the acquisition of Motorola Mobility by Google announced in August 2011 the reverse breakup fee would have amounted to up to $2.5 billion, which compares to a transaction value of only $12 billion. Similarly, in the $24.3 billion acquisition of Forrest Labs by Actavis plc in February 2014, the reverse breakup fee was $1.175 billion, an unusually large percentage for such a large transaction. In both cases, the size of the breakup fee probably was driven by concern over antitrust risk. By imposing punitive breakup fees, the target board can ensure that the acquirer will use its best efforts to resolve antitrust issues—for example, by consenting to the divestiture of business units.

Severity of Losses

After probabilities, the second dimension to losses is severity. Severity is the extent of a loss on a given merger if it were to fail. To illustrate the difference between expected losses and severity, assume that arbitrageurs were to take positions in a large number of mergers that are exactly identical. A small fraction of these mergers will collapse, whereas the rest of the mergers are closed. Assume that the arbitrageur suffers a loss of 25 percent on each of the mergers that collapses. The 25 percent loss is referred to as the severity. Assume that 5 percent of the mergers collapse. The probability of collapse is 5 percent. Statisticians define the expected loss as 0.25 × 0.05 = 0.0125. This means that the arbitrageur would expect to lose on average 1.25 percent due to mergers that collapse. Severity is analogous to the quantity known as loss given default in credit analysis.

It was shown in the previous section that the determination of probabilities involves much guesswork. The determination of severities does even more so. The principal method available to arbitrageurs is a chartist approach, coupled with subjective adjustments. Valuation techniques, such as fundamental valuation or comparables analysis, can be helpful also.

Fundamental techniques can be helpful by giving a point of reference where the stock price should trade absent the merger. But for a variety of reasons, stocks rarely trade where fundamental methods suggest they should trade. When a merger fails, the last thing in arbitrage investors' minds is the theoretical, fundamental value of a company. Most seek to exit their holdings immediately. Therefore, in the short run, technical trading considerations outweigh any fundamental value that stock may rightfully have. For mergers that fail to close over a longer period of time, or where industry conditions are changing, a fundamental approach may yield better estimates.

Nevertheless, the problem with both fundamental and technical methods is that they fail to capture the primary driver of the fall in the target's stock price: the sudden overhang of sell orders by arbitrageurs who want to liquidate their positions when a merger collapses. Fundamental methods are least able to account for this effect. Chart-based methods are generally a little more useful in trading scenarios where fundamental methods cannot be used. The problem underlying the collapse of a target company's stock price has two sources:

- The merger premium. The purchase of a stock is done at a premium to its trading price before the merger. Once the merger is no longer an option, the stock should return to its regular nonmerger trading level.

- The change in the composition of a company's shareholder base. With the announcement of a merger, many long-term investors sell to arbitrageurs. Long-term investors are happy to capture the premium at which the company is acquired but are unwilling to assume the risk that the merger collapses. Arbitrageurs take the opposite position and provide sellers with liquidity. If a merger collapses, arbitrageurs no longer want to hold the stock, and sell. Long-term investors, however, do not buy back the stock immediately, so the overhang of sell orders leads to a drop in the stock price. In some instances, the price can even drop below the level it traded when the merger was announced.

Returning to the acquisition of Autonomy by Hewlett-Packard, an arbitrageur looks at the price range in which the stock traded prior to the proposal by HP. Figure 4.9 is a subset of the chart in Figure 2.1. A shorter time frame has been chosen to highlight the critical period just prior to the announcement of the merger. This chart shows that Autonomy traded between £14.05 and £15.38 on the day before the announcement of the merger. However, focusing only on the last day before the announcement is not sufficient. The chart reveals that Autonomy traded as low as £13.44 on August 9 and as high as £18.29 on June 3. The average price in the three months prior to the announcement was £16.83.

Figure 4.9 Autonomy Prior to Its Acquisition by HP

Because no scientific approach exists to determine an exact level to where the price could fall if the merger had collapsed, guesswork is needed to make sense of the chart. By observing the past trading range of the stock, an arbitrageur would take a conservative approach and choose a price below £15 as a reasonable assumption of the level to which the stock could fall back. If the arbitrageur had bought the stock at a price of £24.92, as was assumed in the earlier example, then the severity amounts to £9.92 per share if a level of £15 were selected:

where

| L | is the severity of the loss. |

| PS | is the postcollapse price at which the stock can be sold. |

| PP | is the purchase price. |

In other instances, a more conservative or more aggressive assumption could be made. These factors should be considered:

- Was there rampant takeover speculation prior to the announcement of the deal? If so, the stock may have traded higher than it would have otherwise. The downside risk should be adjusted accordingly. The arbitrageur should try to determine when rumors first started circulating and at what price the stock traded then.

- What could be the reason for the collapse of the merger? If a material adverse event occurs, the stock will drop well below the preannouncement price. If the fundamentals underlying the business have deteriorated, then the stock would trade lower absent a merger. Conversely, if the fundamentals of the sector are improving, then a deal failure may not have too severe an impact.

- How are the economic environment and the market overall developing? If there is a deterioration of the stock market in general or the industry in which the firm operates, then a drop to below the announcement price is likely. Note that not only the severity is affected by such deterioration. The probability of deal failure increases also, so that an arbitrageur takes a hit on two fronts simultaneously. Conversely, if the stock market has been trending upward strongly, then the downside may be lessened by the generally higher level of stock prices.

- Has the industry or the sector been re-rated? From time to time, the announcement of the acquisition of one firm leads to a re-rating of its entire sector. This is particularly the case when strategic buyers make an acquisition. Investors assume quite reasonably that competitors of the acquirer might now feel pressure to make similar acquisitions, for example in order to secure a supply chain. The result is that valuations in the entire sector will be higher and the chartist approach advocated here will overestimate downside exposure.

As an aside, consideration of the last point by many arbitrageurs simultaneously can introduce a correlation with the overall stock market in merger arbitrage returns. If merger arbitrageurs reassess the downside risk of a position, they will reduce their holding in that stock. If a sufficiently large number of arbitrageurs reduces their exposure at the same time, the spread will widen, which in turn leads to a drop in the performance of merger arbitrage just at the same moment the market corrects. Some of the put option–like characteristics of merger arbitrage can be explained by this effect.

In stock-for-stock mergers, the calculation of loss severities is complicated by the simultaneous exposure to two stocks: a long position on the target firm and a short position in the acquirer. Estimation of the total severity is more complex due to the short leg of the trade. When a large number of arbitrageurs are involved in a stock-for-stock merger, the short side of the arbitrage will undergo a short squeeze if the deal collapses, as all arbitrageurs seek to cover their short positions at the same time. This effect will aggravate loss severities. The arbitrageur will not only lose from the drop of the price of the stock held long but also suffer a loss from the short squeeze. In other word, a stock-for-stock merger yields twice as many opportunities to lose money as a simpler cash merger.

The loss severity on the target is calculated in the same manner as for cash transactions. In principle, an analogous method for the long leg can be used to determine the loss severity of the short leg: By looking at the trading level before the announcement of the merger, a level can be estimated. However, a judgment must also be made about the likelihood of a short squeeze and the potential price that the stock can reach as a result of the squeeze.

The acquisition of Pinnacle Gas Resources by Quest Resource Corp. is a good example of how arbitrageurs can be hit on both sides of the arbitrage in a stock-for-stock merger. Quest proposed on October 16, 2007, to acquire Pinnacle by exchanging each Pinnacle share with 0.6584 of its own shares. Some Quest shareholders were unhappy with this transaction and felt that they would be subject to an unacceptable level of dilution. But the filing by Advisory Research, shown in Exhibit 4.2, contained another hint that Quest would have significant upside should the transaction collapse, and hence that a short squeeze might be possible.

Advisory Research suggested not only that it might purchase more shares but also that it would try to find an acquirer to buy the company, presumably at a premium to its trading price. Some of the technical details about sections 78.416 and 78.423 concern freeze-out provisions under state law, which are discussed in Chapter 8.

As a result of the opposition to the merger, Quest's management renegotiated the terms of the transaction in order to make it more palatable to its shareholders. The exchange ratio was lowered from 0.6584 to 0.5278 only two days after Advisory Research filed its letter with the Securities and Exchange Commission. Nevertheless, approval of the transaction remained difficult for Quest, and the transaction eventually was canceled on May 19, 2008.

The result of the undoing of this merger can be seen in the stock charts of Pinnacle and Quest in Figure 4.10. The spread had been widening for some time. This can be inferred quite clearly through visual inspection of the Pinnacle and Quest charts. Pinnacle's stock price was falling while Quest's was rising. On May 19, Pinnacle's stock dropped severely to under $3 and settled near $2.50 over the next few days. Quests stock price, however, was rising inexorably, from $8.91 on the day before the announcement to $10.81 after the announcement. It even reached $11.99 the following day—a 34.6 percent jump over the closing before the announcement.

Figure 4.10 Pinnacle Resources and Quest Resource Corp. after the Canceled Merger

The increase in Quest matches its trading level before the merger announcement quite closely. It had traded between $9.50 and $11 before the merger was announced in October 2007. For Pinnacle, however, the drop to $2.50 was not easily predictable from a chart alone. The steep drop in the months before the transaction with Quest was a sign that further downside was to be expected if the merger were not to happen. A fundamental analysis would have yielded more reliable target levels than a chartist approach.

Another method to determine loss severities is the quantitative analysis of past transactions that have failed. This method should be more reliable if applied to a large number of transactions. It also has appeal with arbitrageurs grounded in quantitative analysis and also has value in larger organizations, where statistical inferences are preferred over judgment for decision making. However, at any given time, only few transactions fail, so statistical inferences can be misleading.

Historical information about the premia paid in mergers gives some indication to the downside risk on the target. Table 4.3 shows average premia paid by acquirers over the 1-day, 5-day, 30-day, and 90-day prior trading prices in different countries. These numbers are based on Mergerstat's database for transactions between 1995 and mid-2013.

Table 4.3 Average Acquisition Premia over the period 1995-2013

| Average premium | 1-Day | 5-Day | 30-Day | 90-Day |

| United States | 27.6% | 31.2% | 37.2% | 57.6% |

| Canada | 30.5% | 35.1% | 43.2% | 55.8% |

| Australia | 38.7% | 42.% | 48.6% | 55.8% |

| United Kingdom | 16.7% | 20.7% | 32.2% | 41.3% |

| Europe | 19.6% | 23.3% | 28.6% | 38.6% |

Source: Mergerstat, author's calculations. Period covered: January 1, 1995, to June 30, 2013.

Figure 4.11 shows how acquisition premia change over time in the United States and United Kingdom. It is difficult to discern an obvious trend. Nevertheless, it appears that premia have declined somewhat in the United States between 1995 and the financial crisis. Since 2009, they seem to be higher than previously, not only in the United States but also in the United Kingdom. In general, the 30-day premia are higher than 1-day premia. There are two possible explanations for the difference: It indicates either rampant insider trading or that the market anticipates many mergers. In both cases, a stock will trade up to the acquisition price as time approaches the announcement of a transaction. An alternative explanation would be the natural uptrend of markets. Over the period of 1995 to mid-2013, the market has generally traded up. The difference between 30-day and 1-day premia could simply reflect this natural trend. However, the difference is by far greater than what one would expect from a trending market over a short period of 29 calendar days. It should also be noted that the difference between 1-day and 30-day premia has declined since 1995. This supports the insider-trading hypothesis. Regulatory enforcement against insider trading has increased over the last decade, and the numbers suggest that it appears to have a positive effect.

Figure 4.11 Evolution of Acquisition Premia

For an arbitrageur, the significance of these data is that downside risk in the portfolio overall varies over time. Even if each merger is examined on its own merits for the potential loss severity from a collapse in the deal, it can be assumed that premia are somewhat correlated with downside risk.

These numbers can give some guidance to how much downside an arbitrageur might expect on a typical merger. However, it still is worth the effort to examine each transaction individually to get a more accurate sense of the severity that an arbitrageur can expect.

Compared to other analysts of downside risk, in particular participants of the credit derivative markets, merger arbitrageurs tend to have a more sophisticated approach to severity. It is not uncommon to see the pricing of credit derivatives performed with a standard severity (or loss given default) assumption of 40 percent, sometimes with industry-specific variations. Few credit derivative participants will go to the trouble of making a more careful estimation of loss severities. In contrast, merger arbitrageurs routinely estimate separate severities for each of their investments.

Expected Return of the Arbitrage

After an arbitrageur has determined the loss severity and probability of that loss, the risk-adjusted return on the arbitrage is calculated. It will be referred to as the annualized net return:

The principal difference between the gross returns calculated earlier and the net return shown here is that the latter incorporates the possibility of a loss. The gross return in itself is not a very meaningful measure, because it assumes that the merger will be consummated. Naturally, large gross returns are associated with higher risks of deal failure. Therefore, net returns are better measures of potential profitability than just gross returns, because they incorporate risk.

Net returns make most sense when used in the context of a portfolio of merger arbitrage transactions. Even though it is possible to make a net return calculation for a single merger, it is clear that the net return will never be achieved. As a stand-alone number, net returns are not very useful because the outcome of a single merger is a binary one: Either the merger will be consummated and the arbitrageur will earn the gross return, or the merger will fail and the arbitrageur will suffer a loss in the amount of the severity. What I refer to as net returns are also referred to by statisticians as probability-weighted returns or expected returns. The term expected in “expected return” is somewhat of a misnomer. It is highly unlikely that the expected return, or net return, actually is achieved in any single arbitrage transaction. If one were to invest repeatedly in identical mergers, then on average the investor would achieve the net return. Of course, no two mergers are alike, and in practice, a net return calculation is no more than a decision tool. Too much reliance on this number can be dangerous because most of the time it will either be exceeded, or the arbitrageur will suffer a loss.

It is possible to calculate net returns for more than one scenario. For example, a merger may either go through without difficulties or be challenged by antitrust authorities. If it is challenged, there are two possible outcomes: The transaction fails or is approved. Multiple scenarios such as these can also be computed with the previous formula, albeit with minor modifications:

or

where

Pr1, Pr2, and so on signify the probability of each outcome other than a straight passage of the merger.

The various other methods for calculating annualized returns discussed in Chapter 2 can also be used with this formula. It is left as an exercise to the reader.

Some arbitrageurs use decision trees to calculate net returns for mergers with multiple outcomes. Decision trees are a tool that will yield the same result as the last calculation, if done correctly. Which method to use is a question of personal preference. Readers interested in decision trees are encouraged to review the extensive existing literature on that topic. Its application to merger arbitrage should be clear from the techniques discussed in this chapter, and is left as another exercise to the reader interested in the matter.

It is tempting to assign too much significance to net returns as a measure of risk and return. Although they represent probability-weighted returns, the inputs are mostly subjective. Even if quantitative methods are used to determine probabilities, it is difficult to say for sure how much credibility they have. Mergers are subject to a large number of variables that behave very differently under varying economic circumstances. Moreover, most arbitrage portfolios tend to have a limited number of positions, because only a limited number of companies merge at any one time. An overreliance on probabilities in such portfolios can be dangerous.