Key Concepts

Divide administration tasks into centralized activities that benefit all sites and activities specific to each site

Make decisions for each type of data as to whether it should be managed centrally or in the context of individual sites

We have seen how the creation of multiple sites is both beneficial and costly. We have also proposed that the fundamental approach to minimize costs and simplify the administration of multiple sites is to create a single shared platform for all these sites. This shared platform would make use of common hardware and software infrastructure and would also allow the reuse of the same data by multiple sites.

A company that operates many sites must expend considerable effort administering the data used by the sites. This data is necessary for the operation of any commerce site; for example, it would include the product catalog and prices, advertisements and marketing data, customer profiles, and so on. Much of this data is not managed by IT, but rather is manipulated directly by the line of business administrators, using various tools provided to them by the platform.

Let’s now examine in more detail how the various kinds of information on the sites would be administered when a shared platform is used. As we have described, many scenarios require the use of multiple sites, and each one is unique in the data that needs to be managed. To focus the discussion, initially we concentrate on the specifics of administration of a country site. In this chapter, we discuss the administration of sites created for the needs of countries in various parts of the world.

Imagine a multinational seller that does business in many parts of the world and needs to administer sites targeted at specific countries or regions. This seller might be a consumer retailer with global presence, such as IKEA, Staples, or Abercrombie & Fitch. Or it can also be a multinational company that deals mainly with business customers, such as IBM, Honeywell, or Avery Dennison.

For each country where this company sells its products, it needs to create a commerce site. This site must have all the products available in the country, with up-to-date prices and inventory. The company probably wants to create advertisements and run marketing campaigns for each site to maximize its sales. Each site will have customers registered to it, with their profiles, order history, and preferences. Finally, all the sites need to be configured for such country-specific information as languages and currency, and business rules such as acceptable payment instruments, shipping methods, and so on.

In general, when a company manages many country sites, the information that it administers can be either global or country-specific. For example, many sites might use products from the same common master catalog; hence, such catalog data is global and is shared among multiple sites. On the other hand, products that are unique to only one country ought to be treated as site-specific data that is not shared but is unique.

Administration tasks are therefore divided into central administration and site-specific administration. Central administration is concerned with the management of the platform as a whole, on behalf of all sites, and site-specific administration is focused on managing information in the context of an individual site.

For example, the management of the hardware and software of the multisite platform must be done by a central IT organization for the benefit of all sites. Such activities as hardware upgrades, installation of software fixes and new versions, database backups, performance monitoring and tuning, security audits, and so on, are all IT tasks that must be managed centrally.

Another example of central administration is the planning and creation of new sites. When a new site is required, it is often best to delegate the actual creation of the site to a central site planning department. This department would review and approve the need for the site, ensuring that an already-existing site does not already fulfill the need. In addition, central site planning would be responsible for improving or creating additional presentation templates used by the sites, and for the determination of the need for changes to software or hardware.

On the other hand, each individual site requires administrators to manage those aspects of the site that make it unique. For example, a country site can have country-specific products, country-specific marketing activities, or shipping methods that work only within that geographical region.

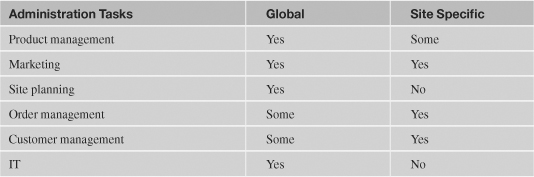

Table 3.1 shows some typical examples of how administration tasks are assigned for country sites that use a shared commerce platform.

From this table, we see that typically for country sites, the responsibilities of central administration include global product management, global marketing, global site planning, and IT. On the other hand, the responsibilities of administrators of each site are order management, customer management, marketing, and country-specific product management. We therefore describe each type of information and how the administrative duties are typically divided for it.

With country sites, global product management is responsible for producing all the detailed product information, including product images, descriptions, comparisons, and the overall structure of categories in the catalog shown to the buyers on the company’s country-specific Web site. There is no need for each site to worry about managing this enormous volume of information, but rather it must be managed centrally, serving the entire company.

However, each country still needs the capability to fine-tune this information to suit the unique needs of its customer base. The most typical fine-tuning is excluding those products that are not to be offered for sale in that country. Frequently, entire categories, or even entire product lines, need to be excluded because they are not available in that country.

From a management point of view, after a country has elected to exclude a category, all the products in the category must not appear on the country’s site. Furthermore, if subsequently the central product management organization adds more products to that category, the new products would also be excluded automatically, without any additional action by the country’s product, marketing, or sales administrators.

To illustrate this point, let’s consider an example of a simple global catalog made available to all countries, as shown in Figure 3.1.

Let’s now imagine how an individual country would make its catalog decisions. For example, Figure 3.2 shows the decisions for the USA catalog.

As you can see, the USA product sales team has made only two decisions: to exclude the T-shirts category and to exclude the Polo shirt. Ideally, because the T-shirts category is excluded, all the products within it are also excluded automatically; hence, both the long- and short-sleeved T-shirts are not for sale on the USA site. Any other products subsequently added to the master catalog placed within the T-shirts category should also never appear on the USA site.

Another type of country-specific catalog decision is the addition of a product unique to one country. For example, in 2009 the Canadian Coca-Cola site offers the Olympic torch relay lapel pin. This product is available only in Canada because Coca-Cola is sponsoring the 2010 Winter Olympics games, which are to take place in Vancouver.

With these kinds of decision-making capabilities, each country retains significant control over its products for sale. At the same time, the bulk of product information is managed centrally, without any duplication of administration effort among countries.

Intuitively, it seems most likely that the administration of the global catalog will be done by a different department than the administration of catalog selections and modifications needed for each country site. After all, the focus of the different administrators is probably quite different. Where the global administrators need to ensure the accuracy and completeness of the information, the country-specific administrators prefer to assume that information is correct and are interested only in making sure that it is applicable to their market.

Because of this different focus, a common way for companies to organize themselves is to actually have a department dedicated to the creation and maintenance of the master catalog. Each country, or group of countries, maintains its own staff to adjust the master catalog to the needs of its site. As a result, the total number of staff necessary for maintaining the catalog consists of the overhead of the global catalog administrators, plus the administrators necessary for individual adjustments needed by each site.

In some cases, it is possible to reduce somewhat the staff requirements, by combining central product management with the responsibilities of managers of one of the country sites. For example, if a large U.S.-based retailer wants to create sites local to other countries, it is possible that the U.S. catalog can actually be used as the global master catalog for the whole platform. It might be easiest for those other country sites to simply use the U.S. catalog as the starting point and then do only the few adjustments necessary to make it available to the customers of each country. This way, the responsibilities of global catalog administration are combined with administration of the U.S. catalog, thereby making the whole operation more streamlined and avoiding unnecessary overhead.

However, this method of using the home country catalog as the basis for the global catalog is often difficult to apply. Normally, the U.S. catalog cannot be used as the basis for the global catalog without globalization information. For example, most likely the U.S.-based product team would enter the product information only in English, but other countries would need the information in their local languages. Therefore, to make use of this approach, it will still be necessary to employ the administrators that add the language- and culture-specific information to the catalog. Although the U.S. site would not need this extra information, other country sites cannot make use of the global catalog until it is added.

Prices can be different between countries due to local market conditions, for example, because of government regulations, import taxes, or simply because of different consumer expectations in that country. Another reason for price differences is that different countries are likely to use different currencies.

It is not common for country sites to convert prices from one currency to another based on current conversion rates. For example, let’s say the list price is US$37.98, and the current conversion rate to British Pound is 1£ = US$1.746. In this case, it is theoretically possible for the system to automatically calculate the price for the British site to be £21.75.

Even though such on-the-fly conversion is relatively easy to set up, few sites make use of it. One reason is that with real-time currency conversion, prices would become unstable, changing every time currency conversion rates change, thereby confusing customers in that country. Another reason is that pricing is not only a matter of crunching numbers, but is also affected by such factors as human psychology. It is common, for example, to see prices ending with 99 cents, such as $29.99 or $39.99. This is an effective psychological mechanism to give the impression that the prices are not actually $30 or $40, respectively, and automatic currency conversion would take away the flexibility of such techniques from the product managers.

For all these reasons, typically pricing is controlled by each country, so each country site must have the capability to specify prices for all products. Correspondingly, it needs staff dedicated to determine and enter product prices.

In some cases, however, all prices are expressed in a single dominant currency, such as U.S. dollar or euro. For example, multiple European sites can actually have the same prices, all expressed in euro. Alternatively, a U.S.-based seller might sell certain products in U.S. dollars even outside the United States. In this case, prices for many products could be the same, expressed in the same currency. In such situations, it could be possible for multiple sites to base their prices on the list price specified with the centrally managed product data.

However, even in these situations each country most likely would need to override the price for at least some products or for products in certain categories. We therefore see two approaches to managing prices with country sites. With the first approach, prices for all products are never managed globally but are entirely administered by each country’s administrators. With the second approach, the global catalog includes list prices available for all countries. However, administrators of each country might override the prices to suit local market needs.

When a multinational seller creates sites for various geographies, typically each geography needs to present information in different languages. Therefore, each site must have the capability to select the languages in which information is presented. If translations are not provided with centrally prepared product data, each geography would need to add such translations.

Generally, experience shows that the best quality translations are prepared in the local country. The reason might be that locally made translations take into account not only the strict language rules, but also the local cultural conventions. Another possible reason could be that translators local to the country are usually very familiar with the language; on the other hand, a central organization might not find the best translation skills and sometimes uses people who are not native speakers in the language.

Whatever the reason for this observation, it is important for the company to be aware of the trade-off in this regard. Doing translations in each country is usually significantly more expensive than concentrating the translation effort in one or two locations. On the other hand, a central translation organization is likely to be disconnected from local culture and hence to produce material of inferior quality.

Therefore, the best practice is to ensure that local countries are always involved in the translation effort, even if it is concentrated in a central location. For example, sometimes translators are hired from the individual countries, working on assignment at the central location. Another possibility is to involve the individual countries in testing the translated material to ensure that it is of sufficiently high quality.

Sometimes a company cannot provide translations for product information in all the necessary languages, either due to financial restrictions or because products are launched before translations are available. In this case, each site must select the language to be used for those products for which translation is unavailable. For example, in a bilingual country like Canada or Belgium, if information is not available in one language, presenting it in the other official language might be acceptable. Another example occurs frequently in the United States, where sometimes sites provide a shopping experience in Spanish. When Spanish information is unavailable, showing the English version instead might be acceptable.

It is therefore important that each site can specify not only the preferred language, but also the second and third choices of languages so that the lower-level choice is automatically used whenever information in the preferred language is unavailable.

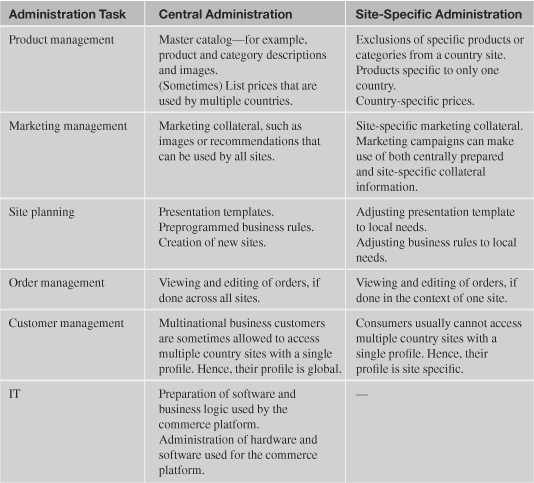

In Table 3.2, you can see the best practices for whether each kind of information is best managed centrally or by each individual site. For each kind of information, this table describes the necessary central and site-specific administration. The column with the “Yes” text indicates where the bulk of work is anticipated to occur. To reduce costs, it is always preferable for the bulk of work to be done centrally, but as we have seen, each site necessarily needs to carry responsibility for some site-specific catalog administration.

Generally, in a multinational company, each country retains a large measure of control over the marketing campaigns that it runs. Thus, for example, each country can make decisions on which campaigns to run, which products to advertise, and even how to promote the products. At the same time, in some situations the global marketing managers can help their country-specific counterparts by preparing marketing collateral centrally.

Sometimes a centrally managed global marketing organization prepares marketing collateral that can be used worldwide. For example, the Coca-Cola soft drink brand is recognized all over the world by its logo and its advertisements. This global marketing collateral is reflected in all of its Web sites for each country where it does business.

This global marketing material can range from specific advertisements and text messages to entire advertising scenarios that are put together based on detailed research with focus groups or based on marketing intelligence. The marketing administrators for each country site should then make use of those portions of the collateral that they see fit. The essential idea is to allow country marketing managers the flexibility to focus on running the campaigns rather than spending huge resources in each country on preparing the collateral.

Nevertheless, given that marketing is an activity inherently related to the cultural environment of each site, it is usually unavoidable for marketing managers for individual country sites to have to create additional locally specific marketing collateral and make use of that in their marketing campaigns. This local material can include country-specific advertisements, promotions, or attention-getting multimedia content. Local administrators might also need to make adjustments to the centrally prepared collateral, to account for local culture, language, and regulations. In another common situation, an entire marketing campaign is specific to one country, such as country-specific contests or gift giveaways. Going back to the Coca-Cola example, the Canadian Coca-Cola site has a “You Could Carry the Olympic Flame” contest, which is inherently specific to Canada because this campaign is making use of Coca-Cola’s sponsorship of the 2010 Winter Olympic games in Vancouver.

The other way of sharing marketing material is not just to make images, text, or other collateral available to the local marketing managers, but to actually create and run marketing campaigns centrally. In this situation, the country sites included in the campaign automatically participate in them—for example, showing a certain advertisement on the home page or recommending certain products on the checkout page. This means that, without any involvement of administrators of the affected country sites, customers visiting these sites would automatically be viewing the marketing messages of these global campaigns.

Inherently, such centrally managed campaigns have fewer capabilities than locally managed marketing campaigns. For example, if the campaign scenario includes issuing a discount coupon and sending an e-mail to all customers who have met certain criteria, it would be imprudent to impose these activities on countries without ensuring that these offers are available in each country.

One important limitation is that the company must ensure that the centrally managed marketing campaigns do not violate local cultural or ethical conventions. For example, let’s say a global campaign uses a customer’s browsing history, and if it’s determined that the customer has visited a related Web site, a certain offer is shown. Such marketing techniques of using customers’ previous histories can be highly restricted by privacy regulations in some countries. Therefore, it would be unwise to use these techniques in a centrally managed marketing campaign because such a campaign would run a high risk of violating local regulations.

As a rule, centrally managed marketing campaigns ought to be used very carefully, and only when it is deemed that the campaign must truly be global in scope. Perhaps the most common example in which a centrally managed advertising campaign would apply is a worldwide launch of an important product. If the product is truly high profile, and it is introduced simultaneously worldwide, it could make sense for the global marketing administrators to reserve an area on all the country sites to advertise that product for the duration of the product launch campaign.

Even if a company does decide to make use of such globally imposed campaigns, it would be a good idea to give the administrators of each site the ability to opt out of the campaign. By opting out, the country sites’ administrators make the decision that this entire centrally prepared campaign is inapplicable to their country, and therefore their site will not show the corresponding content. With this opt-out option, the administrators cannot fine-tune the campaign or make use of portions of the centrally prepared content. However, this option would be important if they realize that the country’s site will end up in legal trouble if they allow the globally imposed campaign, and yet there is no time to explain the situation to the central marketing managers and to convince them to change the campaign content to comply with local regulations.

The best practice is that global marketing management focuses only on the preparation of marketing collateral, which it makes available to country-specific marketing administrators. The central marketing department can also put together recommendations on how to employ certain content and when it should be used. The administrators of each country site should have flexibility on selecting the materials that they use or preparing their own material. Using this combination of centrally and locally prepared collateral data, each country site might schedule its marketing campaigns and assign them to the appropriate areas of the country site.

If the company wants to impose restrictions on the campaigns of different countries, such as making sure that all the sites have consistent marketing content, this should be done by communicating the instructions to the administrators and relying on them to conform to the company’s marketing directives.

The tactic of creating the entire campaign centrally and imposing it on all sites should be used only for truly global product events, such as important product announcements. Also, this approach must be limited to advertising images only, without employment of complex marketing scenarios.

Typically, in a multinational company, it should be the job of a central corporate organization to make decisions to create new sites. Although allowing each country to create its own sites might seem like a good idea, it is better to avoid delegating this responsibility because inevitably, even with shared infrastructure, each site adds to the overall operating complexity and cost. Therefore, the best practice is for this task to be handled by a central site planning organization, based on overall corporate business planning, and based on requirements of each country. In some cases, for example, a country might request to create additional sites for its market, or a decision might need to be made to split a site that served several countries in a region into separate sites for each country. In all these cases, it should be the job of site planning to not only review the needs for new sites, but also to actually create the sites.

After site planning has created the new site, it is not yet ready to be made available to the customers of that country. Before the site can be put into production, the country’s marketing and product administrators must adjust it to local needs. This applies not only to the catalog and marketing content, but also to some aspects of the site’s presentation. For example, the administrators might want to set the welcome text on the home page or to modify the privacy statement. Sometimes some of the site capabilities need to be disabled, such as disallowing customer product reviews for that country or changing the payment methods allowed on the site.

Generally, with country sites, the company would like to make sure that all the sites share a similar overall look or theme, reflecting the company’s image. Because of the need for consistency, the company is usually not interested in giving local administrators too much flexibility in varying the look-and-feel of their sites. Site planning must therefore be careful to understand the needs of the various countries and to ensure that the platform has enough flexibility to allow such locally managed modifications, but does not give options that would endanger the consistency of the sites.

For example, the administrators of the site usually need to change various text messages on the home page. However, often it is better not to give the country site administrators the ability to change the colors of the site or to alter the placement of the navigation bar.

A presentation template provides a unique look and flow for a site. It determines how the content of the site is presented to the customers and how the customers are guided through the site. The presentation template determines, for example, the set of pages that the site consists of, the navigation of the catalog, the checkout flow, customer profile management, and order history display.

If a company wants to maintain a single brand image, it is best for the presentation template to be developed centrally. This way, all the company’s sites in all countries look similar, and customers have a consistent experience associated with the company’s sites.

Within this common experience, each country site should be able to make adjustments to make the site appropriate to its needs. For example, in countries where several languages are in use, customers might be asked to select their preferred language before entering the welcome page, but other countries will show the welcome page immediately. The administrators who manage a country site might also want to change the text on some of the pages or even upload different content, such as images or flash demos.

Well-written software should enable the country site administrators to make such changes on their own, without having to ask IT personnel or any of the company’s site planning staff. In other words, a shared commerce platform must ensure that its presentation template is both flexible and adaptable to the needs of each country.

Nevertheless, in some cases it is impossible to use a single presentation template for all countries. This can be due to language translations, where a given amount of text tends to take a lot more space in one language compared to another language. In this case, it is convenient to create a different presentation template, which is more suitable for use by the particular language group.

Another reason for needing multiple presentation templates is to accommodate local culture and conventions. For example, in China, Web pages are often quite long, with many products shown on the welcome page. On the other hand, in North America, pages tend to be relatively short, not exceeding the length of the screen.

For these reasons, often the site planning team needs to prepare several presentation templates. When creating each site, the team would then specify the particular presentation template applicable, thereby making sure that each country site is best-suited for the local environment.

Business rules can vary significantly between countries. For example, in North America typically payment is deposited only after the products are shipped, but in other geographies payment can be collected as soon as the order is placed. Another example is payment methods: In North America, typically the entire payment is collected for the order, but in South America, it is very common to divide payment into multiple installments. In addition, there could be differences in the way taxes are applied or even in the way amounts are rounded off after taxes are applied. A classical example of rounding rule differences is that in the United States, all calculations must be rounded off to the nearest cent, which is one hundredth of the dollar, but in Japan, transactions may be rounded to the Yen, and there are no fractions in this currency unit.

With such differences in business logic proliferating between countries, it is important that each site can apply site-specific rules where necessary. Therefore, the administrators of each site must be given the tools to specify the business rules that they need.

Sometimes these business rules need to be specified by line of business administrators; for example, ideally, they need to set shipping charges or to establish approval policies. At the same time, for many business rules it is acceptable if they are specified by IT personnel, as part of the preparation and configuration of the software used by the commerce platform. For example, currency rounding rules are usually configured once and are not modified; hence, configuring these rules is usually an IT job.

Therefore, it is critical to the success of the commerce platform that it uses well-written software that provides the necessary flexibility for the administrators of country sites. The platform must provide tools to the line of business administrators to configure their sites, without having to ask IT personnel for every change that they make.

For example, the platform might provide an administration console, in which business managers could enter their site’s shipping rules, shipping charges, payment rules, and so on. Ideally, the line of business administrators should have the flexibility to manage all aspects of their sites.

In reality, this infinite flexibility is, of course, impossible to achieve. What happens instead is that the software is configured for many possible variations of business rules, such as different types of approval workflows or different possible payment methods. The business administrators can then select the business rules that apply best to their site and sometimes add additional configuration to adapt the rules to their local environment.

If the managers of a country site come up with a new requirement that incorporates a new kind of business rule or a new workflow, this requirement should be given to the developers of the shared commerce platform. Such requirements would be considered for the next release of the platform, based on such factors as the benefits of these improvements to this site and to other sites.

It is important for the company to retain central control over the software used by the shared commerce platform. The company cannot allow each country to write its own programs to handle business rules of their site and contribute them to the system. First, such distributed development would end up being quite expensive, with each country having to hire essentially the same skills for similar kinds of work. Furthermore, experience has shown that software quality is difficult to ensure; therefore, it is better if software is developed and tested by a single organization, based on requirements of each country.

One of the biggest fears of business managers whose site operates on a platform shared by other sites is that their country’s requirements will not be accepted or implemented on time by the central IT organization. We discuss this concern in more detail in Part II of this book, especially in Chapter 9, “Organizational Resistance,” and in Chapter 10, “Managing Requirements.”

However, now the important point is that, despite this concern, the company’s management must be careful to ensure the development of the commerce platform and its supported business rules is centralized to a single group in the multinational company.

Normally, order management and payment are the responsibility of each country or region. It therefore makes sense to ensure that each country has the tools to review and edit customer orders in the context of only its country, without being exposed to orders from other geographies. For example, a shopper viewing the British site should not see any orders or shopping carts that she might have created on the U.S. site. Similarly, the order administrators must have the ability to see orders for each country, rather than having to sort through all orders placed in the system.

On the other hand, it is very common for multinational companies to enable a single call center to take telesales orders from multiple countries. Therefore, when a sales agent takes an order or provides information to a customer, it is important for that agent to have access to all the country sites and to select the country site as the context for a conversation with a customer.

If a company employs a single organization for managing orders in several countries, this organization effectively becomes the central administrator of orders in these sites. For example, a company could create organizations to manage all orders in Europe and another organization for managing orders in the United States. In this situation, order administration truly becomes a centralized task; that is, it is the responsibility of a central organization done on behalf of multiple sites. The platform must, therefore, enable administrators to view and search through all orders in the system.

Often, even if a company needs only a single approach, it might require another one in the future. For example, even if currently each country manages its own orders, in the future the company might introduce a global call center. Similarly, even if currently all orders are managed centrally, at some point some of the larger countries might demand their own dedicated call centers.

For this reason, it is usually a good idea to enable both types of order management. In other words, ideally the platform should allow administrators to view and edit orders in the context of each country and look at orders globally.

The key question with customer management is whether customers that have profiles with one site should be recognized and given access to their profiles on another country’s site. So, for example, if a U.S. customer wants to order from the European site, should that customer be able to log in to the European site using a U.S. user ID?

This question does not have a single answer that applies to all possible cases. Each multinational seller must consider its situation, based on the needs of its business. In general, there are two kinds of factors to consider: the ease of doing business for the company itself and the convenience of the customer.

From the seller’s point of view, allowing customers to use a single profile on multiple sites can create business complexities that are difficult to overcome. Sometimes the countries’ regulations might not even allow such access of foreign customers to a local site. Another restriction might have to do with the use of customer profiles for marketing campaigns, which can have varying regulations in different countries. Hence, even if the seller does want to allow the sharing of customer profiles between country sites, the legal implications must be thoroughly investigated first.

Sometimes the company might want to ensure that its customers always order from its home sites. The reason for this restriction is to avoid having to deal with multicountry transactions—for example, where orders coming from one country result in returns in another country. Another possible reason to disallow customer profile sharing among sites is to avoid confusion in the statistics data collected for the purpose of market analytics. Such statistical information can be easier to analyze if it is clearly known that the customer base of each site can be considered fully independent of customers of other sites.

In consumer retail, from the customers’ point of view, there is rarely any benefit from the ability to use their profiles in multiple countries. Most typically, retail shoppers use the site of the country where they reside and are not really interested in knowing about other country sites.

However, in B2B scenarios, this situation is different, and the ability to access multiple sites can be valuable to customers. For example, if a customer is a multinational company or at least a company with presence in multiple countries, to it being able to access all the supplier’s country sites and place orders wherever its customers need them is very convenient.

One key benefit of sharing profiles among country sites for business customers is that the profile contains not only organizational addresses and payment methods, but also the negotiated pricing and product terms. The ability to make use of the negotiated contract worldwide is of great benefit to such business customers. Therefore, the sales organization of a multinational B2B seller must make decisions as to which countries each customer should be allowed to access with its contract terms and conditions.

On a shared platform, the data can be viewed as falling into one of two categories: shared data, which is used by many sites; and site-specific data, which is relevant to only one site. Table 3.3 summarizes the various kinds of administration needed for country sites.