Chapter 4: Selecting and Using Lenses with the Nikon D3300

I always stress that lenses are one of the most important investments for your camera system. A good lens is an investment that will outlast your camera by many years. Because Nikon has removed the Anti-Aliasing/Optical Low Pass Filter from the sensor on the D3300, increasing the acuity of the sensor, the right lens can mean the difference between a good image and a stunning image.

The lenses that you attach to your camera affect not only sharpness, but also color and contrast. Additionally, the interchangeability of lenses on the D3300 allows you to use lenses to achieve visual effects. You can use a wide-angle lens to distort spatial relations and lines, a telephoto to make far-off objects appear closer, or a macro lens to get close up and show detail that can’t be perceived unaided by the human eye.

A high-quality lens is an investment that should outlast many dSLR camera bodies.

Deciphering Nikon Lens Codes

If you’re a relative newcomer to the world of interchangeable-lens cameras, then you may notice when shopping for lenses that there are a lot of different codes and letters on these lenses. For example, the D3300 kit lens in Nikon nomenclature is AF-S DX NIKKOR 18–55 f/3.5–5.6G VR II. So, what do all of these letters mean? Here’s a simple list to help you decipher them:

- AI/AI-S. These are Auto Indexing lenses. Lens apertures are held wide open by a mechanism in the camera so that the most light can get through the viewfinder to make viewing bright and easy. The camera automatically adjusts the aperture diaphragm down to the selected setting when you press the shutter-release button. All lenses, including autofocus (AF) lenses made after 1977, are Auto Indexing, but when referring to AI lenses, most people generally mean the older, manual-focus (MF) lenses.

- E. These were the budget series of manual focus lenses from Nikon. They were made to be used with lower-end film cameras such as the EM, FG, and FG-20. Although these lenses are compact and often constructed with plastic parts, some of them — especially the 50mm f/1.8 — are of good quality. These lenses are also manual focus only. E lenses are not to be confused with Nikon Perspective Control (PC-E) lenses.

AI/AI-S and Series E lenses do not allow for auto-exposure or metering because they don’t have a CPU to communicate data with the camera body.

- D. Lenses with this designation convey distance information to the camera to aid in metering for exposure and flash.

- G. These are lenses that lack a manually adjustable aperture ring, so you must set the aperture on the camera body. Like D lenses, G lenses also convey distance information to the camera. Most current Nikon lenses in production are G lenses.

- AF, AF-D, AF-I, and AF-S. All of these codes denote that the lens is an autofocus (AF) lens. The AF-D code represents a distance encoder for distance information; AF-I indicates an internal focusing motor; and AF-S represents an internal Silent Wave Motor.

- DX. This code lets you know that the lens is optimized for use with the Nikon DX-format sensor.

Full-frame lenses do not carry an FX designation, and you can use them effectively on DX cameras, albeit with a smaller angle of view than on an FX camera.

- VR. This code tells you that the lens is equipped with the Nikon Vibration Reduction (VR) image-stabilization system. The latest lenses from Nikon employ a technology known as VR-III, which is capable of detecting both side-to-side and up-and-down motion, and Nikon claims that you can handhold your lens at up to 5 stops slower than a non-VR lens. All of the Nikon Vibration Reduction technology (VR, VR-II, and VR-III) is simply designated as “VR” on the lens.

- ED. This code indicates that some of the glass in the lens is Nikon Extra-Low Dispersion glass, which is less prone to lens flare and chromatic aberrations.

- Micro-NIKKOR. This is the designation for the line of Nikon macro lenses.

- IF. This stands for Internal Focus. The focusing mechanism is inside the lens, so the front of the lens doesn’t rotate when focusing. This feature is useful when you don’t want the front of the lens element to move, such as when using a polarizing filter. The internal focus mechanism also allows for faster focusing.

- DC. This stands for Defocus Control. Nikon offers only a couple of lenses with this designation. They make the out-of-focus areas in the image appear softer by using special lens elements to add spherical aberration. The parts of the image that are in focus aren’t affected. Currently, the only Nikon lenses with this feature are the 135mm and the 105mm f/2. Both of these are considered portrait lenses.

- N. On some of the higher-end Nikon lenses, you may see a large golden N. This means the lens has Nikon Nano-Crystal Coating, which is designed to reduce flare and ghosting.

- PC-E. This is the designation for Nikon Perspective Control lenses. The E means that it has an electromagnetic Auto Indexing aperture control instead of the typical mechanical one found in all other AI lenses.

Lens Compatibility

Nikon has been manufacturing lenses since about 1937 and is well known for making some of the highest-quality lenses in the industry. You can use almost every Nikon lens made since about 1977 on your D3300, although some lenses will have limited functionality. In 1977, Nikon introduced the Auto Indexing (AI) lens. Auto Indexing allows the aperture diaphragm on the lens to stay wide open until the shutter is released; the diaphragm then closes down to the desired f-stop. This allows maximum light to enter the camera, which makes focusing easier. You can also use some of the earlier lenses, now referred to as pre-AI, but the camera’s auto-exposure functions and metering will not work. All exposure settings must be calculated and set manually.

There are a number of apps that allow you to take exposure readings with your phone. I use a free one called LightMeter Free.

In the 1980s, Nikon started manufacturing autofocus (AF) lenses. Many of these lenses are very high quality and can be found at a much lower cost than their 1990s counterparts, the AF-D lenses. The main difference between AF lenses and AF-D lenses is that the AF-D lenses provide the camera with distance information based on how far away the subject is when you focus on it. Both types of lenses are focused with a screw-type drive motor inside the camera body. Unfortunately, to reduce the size and weight of the D3300, the camera body isn’t equipped with a built-in focus motor. You can only use AF/AF-D lenses for manual focusing, although metering and auto-exposure work perfectly.

Although these older lenses offer a great way to save money, I no longer recommend them as highly as I used to because of the high-resolution sensors in the newer cameras such as the D3300. These lenses are optimized for film cameras and can show more flare due to inferior lens coatings as well as reduced contrast and less-accurate color rendition.

The current Nikon line is the AF-S lens. AF-S lenses have a Silent Wave Motor built in to the lens. The AF-S is an ultrasonic motor that allows lenses to focus much more quickly than traditional, screw-type lenses. It also makes focusing very quiet. Most of these lenses are also known as G-type lenses. These lenses lack a manual aperture ring; you control the aperture by using the Command dial on the camera body. Nikon offers a full complement of AF-S lenses for the D3300, ranging from the ultrawide 10–24mm f/3.5–5.6G to the super-telephoto 600mm f/4G.

The first incarnation of the Silent Wave Motor from Nikon was called AF-I. These are long, expensive telephoto lenses, but they work perfectly with the D3300.

The DX Crop Factor

You may often hear or read about something called the crop factor. This concept is often confusing to newer photographers, especially those who are unfamiliar with 35mm film photography. The crop factor is a ratio that describes the size of a camera’s imaging area as compared to another format; in the case of SLR cameras, the reference format is 35mm film.

SLR camera lenses were initially designed around the 35mm film format. Photographers use lenses of a certain focal length to provide a specific field of view. The field of view, also called the angle of view, is the amount of the scene that’s captured in an image. This is usually described in degrees. For example, when you use a 16mm lens on a 35mm camera, it captures 107 degrees of the scene, which is quite a bit. Conversely, when you use a 300mm focal length, the field of view is reduced to a mere 6.5 degrees, which is a very small part of the scene. The field of view is consistent from camera to camera because all SLRs use 35mm film, which has an image area of 24mm × 36mm.

With the advent of digital SLRs, the sensor was made smaller (15.6mm × 23.5mm) than a frame of 35mm film to keep costs down because full-frame sensors are more expensive to manufacture. This smaller sensor size was called APS-C or, in Nikon terms, the DX-format. When these same lenses are used with DX-format dSLRs, they have the same focal length they’ve always had, but because the sensor doesn’t have the same amount of area as film (or an FX sensor), the field of view is effectively decreased. This causes the lens to provide the field of view of a longer focal length lens when compared to images taken on a camera with an FX sensor or 35mm film.

Fortunately, the DX sensors are a uniform size, thereby supplying consumers with a standard to determine how much the field of view is reduced on a DX-format dSLR with any lens. The digital sensors in Nikon DX cameras have a 1.5X crop factor, which means that to determine the equivalent focal length of a 35mm or FX camera, you simply have to multiply the focal length of the lens by 1.5. Therefore, a 28mm lens provides an angle of coverage similar to a 42mm lens, a 50mm is equivalent to a 75mm, and so on.

An easy way to figure out the DX equivalent focal length is to divide the focal length by 2, and then add the quotient to the original focal length. For example, take a 50mm lens: 50 divided by 2 is 25, and 50 plus 25 equals 75. The equivalent focal length in 35mm (or FX) is 75mm.

Nikon has created specific lenses for dSLRs with DX sensors. These lenses are known as DX-format lenses. The focal length of these lenses was shortened to fill the gap to allow true super-wide-angle lenses. These DX-format lenses were also redesigned to cast a smaller image inside the camera so that the lenses could actually be made smaller and use less glass than conventional lenses. The byproduct of designing a lens to project an image circle to a smaller sensor is that these same lenses can’t effectively be used with FX-format and can’t be used at all with 35mm film cameras (without severe vignetting) because the image won’t completely fill an area the size of the film or FX sensor.

There are some upsides to this crop factor. Lenses with longer focal lengths now provide a bit of extra reach. A lens set at 200mm now provides the same amount of coverage as a 300mm lens, which can offer a great advantage for sports and wildlife photography, or when you can’t get close enough to your subject. Also, when using a lens designed for FX cameras, the sensor only records image information from the center of the lens, which is generally sharper.

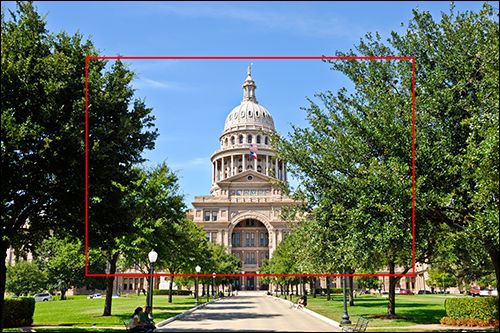

4.1 This image was shot with a 28mm lens on a Nikon FX camera. The area inside the red square is what would be captured with the same lens on a DX camera, like the D3300.

Another advantage of DX lenses is that, because of their relatively small size, they are less expensive to manufacture and, therefore, the lenses are less expensive than their full-frame counterparts.

Third-Party Lenses

Other companies also make lenses for Nikon cameras. These lenses are referred to as third-party lenses or sometimes, albeit less frequently, nonmanufacturer lenses. What this means is that the company that makes the lenses isn’t affiliated with the manufacturer (first-party) or the purchaser (second-party), but is its own entity (third-party).

Previously, third-party lenses were considered inferior substitutes to OEM (Original Equipment Manufacturer) lenses, and in the past that was true. However, in the last 10 years, the digital revolution has brought a huge resurgence in photography, and third-party lens manufacturers have stepped up their game to provide very high-quality lenses at lower prices than those sold by Nikon. While most third-party lenses don’t stand up to Nikon professional-grade lenses as far as build quality, third-party lenses are great alternatives to high-end to lower-level Nikon consumer lenses. If you’re looking for a relatively inexpensive, fast, constant-aperture zoom with good image quality, then a third-party lens is likely the answer.

There are three major players in the third-party lens game: Sigma, Tokina, and Tamron. You may see other brands such as Vivitar and Promaster, but these lenses are usually made by one of the three and rebranded.

Sigma is a company that has been making lenses for more than 50 years, and was the first lens manufacturer to make a wide-angle zoom lens. Sigma makes excellent, high-quality lenses. Almost all current Sigma lenses are available with what Sigma calls an HSM, or Hyper-Sonic Motor. This is an AF motor built inside the lens. It operates in a similar fashion to the Nikon AF-S, or Silent Wave Motor. This enables almost all current Sigma lenses to autofocus perfectly with the D3300.

Sigma has recently announced some new high-end lenses (called their Global Vision lenses) that can be used with DX cameras such as the D3300. They all have HSM motors and include the 30mm f/1.4; a redesigned 17–70mm f/2.8–4 Macro OS; the pro telephoto 120–300mm f/2.8 OS, an all-in-one zoom; the 18-200 f/3.5-6.3 DC Macro OS; and the groundbreaking 18–35mm f/1.8, the first zoom lens to ever achieve an aperture wider than f/2.8. These are also the first lenses that enable the user to connect the lens to a computer via a USB dock and use proprietary Sigma software to update firmware and make micro-adjustments for focusing. This is an amazing new feature. Sigma is blazing new trails in lens technology. Sigma Global Vision lenses are a viable and affordable alternative to professional offerings from Nikon.

Tokina only offers a few lenses that are fully compatible with cameras that don't have a built-in focus motor, like the D3300. The wide-angle lenses are the 11–16mm f/2.8 Pro DXII, the 12–24mm f/4 Pro DXII, and the 16–28mm f/2.8 Pro FX (this lens also works with full-frame cameras, such as the Nikon D600). Most other current Tokina lenses can be used with the D3300 as manual focus only.

Tamron is another major player in the third-party lens market. The company currently offers about a half dozen lenses that are equipped with a built-in motor to focus with the D3300, with the 17–50mm f/2.8 being the most popular, inexpensive fast zoom lens. Tamron has been working through some problems with its built-in focus motor technology, so there are a few different iterations of its most popular lenses. It has a standard screw-type focus technology, referred to as Built-in-Motor (BIM), that focuses very slowly and loudly with an internal focus motor. It also has the Piezo Drive (PZD) and the Ultrasonic Drive (USD), which are recent additions that are comparable to the Nikon Silent Wave or AF-S lenses. Only lenses with the BIM, PZD, or USD designations will autofocus with the D3300.

Types of Lenses

As I mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, one of the most important features of SLR cameras is the ability to use many types of lenses. This allows you to control the aspect in which the image is displayed. Different types of lenses are designed to provide certain effects. The lenses you choose allow you to control the artistic direction of your photography.

Wide-angle lenses

The focal-length range of wide-angle lenses starts at about 10mm (ultrawide) and extends to about 24mm (wide angle). Many of the most common wide-angle lenses on the market today are zoom lenses, although a few prime lenses are available. Wide-angle lenses are typically rectilinear, meaning that the lens has molded glass elements to correct the distortion that’s common with wide-angle lenses; this keeps the lines near the edges of the frame straight rather than curved. Fisheye lenses, which are also a type of wide-angle lens, are curvilinear; the lens elements aren’t corrected, resulting in severe optical distortion (which is desirable in a fisheye lens).

Wide-angle lenses have a short focal length, which projects an image onto the sensor that has a wider field of view; this allows you to fit more of the scene into your image. In the past, ultrawide-angle lenses were rare, prohibitively expensive, and out of reach for most nonprofessional photographers. These days, it’s easy to find a relatively inexpensive ultrawide-angle lens. The following list includes some of the ultrawide-angle lenses that work best with the D3300:

- AF-S NIKKOR 10–24mm f/3.5–4.5G. This is a great compact, ultrawide-angle lens. It’s nice and sharp, and balances well on the D3300. The only downside is that it is a little pricey compared to third-party lenses of the same caliber.

- Tokina 11–16mm f/2.8 Pro DXII. This is one of the only ultrawide lenses available with a fast, constant, built-in focus motor that allows the D3300 to autofocus. The zoom range is rather small, but when using an ultrawide lens, most photographers tend to stay at the wide end of the range anyway.

Image courtesy of Nikon, Inc.

4.2 The NIKKOR 10–24mm f/3.5-4.5G lens.

- Sigma 10–20mm f/3.5 and f/4–5.6 DC HSM. Sigma offers two lenses in this range: the f/3.5 constant-aperture version and the variable-aperture f/4–5.6 version. Neither of these is quite as good as the Nikon lens, but they are more affordable. If you do a lot of low-light, handheld shooting, the f/3.5 version is the better option. If you shoot mostly in daylight or photograph landscapes at smaller apertures with a tripod, the cheaper f/4–5.6 lens is a good option.

- Sigma 8-16mm f/4.5-5.6 DC HSM. For those of you that want the widest angle of view possible (without resorting to a fisheye) this is the widest choice of any lens out there. The difference of 2mm doesn’t sound like a lot, but it really makes a big difference.

Wide-angle lenses are perfect for a variety of subjects. The perspective you get from a wide-angle lens isn’t like anything that can be seen with the human eye. You can use this lens to create some very bold and interesting images. Once you get used to seeing the world through a wide-angle lens, you may find that you look at your subjects and the world in general in a different way.

I always try to find interesting lines and angles for use with my wide-angle lenses. There are many factors to consider when you use a wide-angle lens. Here are a few:

- Deeper depth of field. Wide-angle lenses allow you to get more of the scene in focus than you can with a midrange or telephoto lens at the same aperture and distance from the subject.

- Wider field of view. Wide-angle lenses allow you to fit more of your subject into your images. The shorter the focal length is, the more of the subject you can fit into a shot. This can be especially beneficial when you shoot landscape photos and want to fit an immense scene into your photo, or when photographing a large group of people.

- Perspective distortion. Using wide-angle lenses causes things that are closer to the lens to look disproportionately larger than things that are farther away. You can use perspective distortion to your advantage to emphasize objects in the foreground if you want the subject to stand out in the frame.

- Handheld shooting. At shorter focal lengths, it’s possible to hold the camera steadier than you can at longer focal lengths. At 14mm, it’s entirely possible to handhold your camera at 1/15 second without worrying about camera shake.

- Environmental portraits. Although using a wide-angle lens isn’t the best choice for standard close-up portraits, wide-angle lenses work great for environmental portraits where you want to show a person in his or her surroundings.

Wide-angle lenses can also help pull you into a subject. With most wide-angle lenses, you can focus very close on a subject while creating the perspective distortion for which wide-angle lenses are known. Don’t be afraid to get close to your subject to make a more dynamic image. The worst wide-angle images are the ones that have a tiny subject in the middle of an empty area.

Wide-angle lenses are very distinctive in the way they portray your subjects, but they also have some limitations that you may not find in lenses with longer focal lengths. Here are some pitfalls that you need to be aware of when using wide-angle lenses:

- Soft corners. The most common problem with wide-angle lenses, especially zooms, is that they soften the images in the corners. This is most prevalent at wide apertures, such as f/2.8 and f/4.0; the corners usually sharpen up by f/8.0 (depending on the lens). This problem is most noticeable in lower-priced lenses. The high resolution of the D3300 can really magnify these flaws.

4.3 A wide-angle shot taken with a Nikon 10–24mm f/3.5–4.5G wide-angle lens at 12mm. Exposure: ISO 400, f/11, 1 second.

- Vignetting. This is the darkening of the corners in an image. Vignetting occurs because the light necessary to capture such a wide angle of view must come in at a very sharp angle. When the light comes in at such an angle, the aperture is effectively smaller. The aperture opening no longer appears as a circle, but more like a cat’s eye (you can see this effect in the bokeh at the edges of very fast lenses). Stopping down the aperture reduces this effect, and reducing the aperture by three stops usually eliminates any vignetting.

- Perspective distortion. Perspective distortion is a double-edged sword: it can make your images look either very interesting or very terrible. One of the reasons that a wide-angle lens isn’t recommended for close-up portraits is that it distorts faces, making the nose look too big and the ears too small. This can make for a very unflattering portrait.

- Barrel distortion. Wide-angle, and even rectilinear lenses, are often plagued with this specific type of distortion, which causes straight lines outside the image center to appear to bend outward (similar to a barrel). This can be undesirable when doing architectural photography. Fortunately, Photoshop and other image-editing applications enable you to fix this problem relatively easily.

Standard zoom lenses

Standard (or midrange) zoom lenses fall in the middle of the focal-length scale. Zoom lenses of this type usually start at a moderately wide angle of around 16mm to 18mm and zoom in to a short telephoto range between 50mm and 85mm. These lenses are perfect for most general photography applications. In fact, they can be used successfully for everything from architectural to portrait photography. This type of lens covers the most useful focal lengths and will probably spend the most time on your camera. For this reason, I recommend buying the best quality lens you can afford. Here are some options for midrange lenses:

- Sigma 18–35mm f/1.8 DC HSM | A. This is a new technological marvel of a lens from Sigma. Although it covers a relatively short range, this is the fastest zoom lens ever created. It allows for shutter speeds as fast as a fast prime lens, but with the versatility of a zoom lens. The fast aperture also allows a shallower depth of field than you can get with any zoom lens of the same focal length, for creative use of depth of field for more artistic shots. Although this lens has a very short range, which some people may find limiting, it spends a lot of time on my camera.

Image courtesy of Sigma, Inc.

4.4 The Sigma 18–35mm f/1.8 DC HSM | A lens.

- Tamron 17–50mm f/2.8 Di II. This is a very popular alternative to the Nikon lens for a fast aperture zoom. There are two versions of the Di II lens: the VC (Vibration Compensation) and non-VC. However, you should be aware that there is also an earlier Di version that doesn’t have a built-in focus motor and won’t autofocus with the D3300.

- Sigma 17–70mm f/2.8–4 HSM OS Macro | C. This is one of my favorite lenses for DX cameras, and it’s easily the most versatile lens I’ve ever owned. It’s relatively fast and good for low-light shooting with Optical Stabilization. It’s also very sharp and, although not a true macro lens, it gets you close enough. The best part is that it’s not overly expensive. I recommend this lens over all other standard lenses in its class.

In the standard range for primes, the most popular are the 30–35mm normal lenses. They are referred to as normal because they approximate the same field of view as the human eye. The Nikon 35mm f/1.8G is a competent, inexpensive, fast normal lens, as is the even faster Sigma 30mm f/1.4. I recommend that every photographer carry a fast prime lens in his camera bag.

Image courtesy of Nikon, Inc.

4.5 The Nikon 35mm f/1.8G DX lens is a favorite of many photographers.

Nikon now offers two versions of the 35mm f/1.8G. One is made for DX and the other can be used on FX or DX cameras. The newer FX version is about $400 more than the DX model. Keep this in mind when shopping for a Nikon 35mm f/1.8G lens. The DX version is the AF-S DX 35mm f/1.8G.

Telephoto lenses

Telephoto lenses have very long focal lengths that are used to get a closer view of distant subjects. They provide a very narrow field of view and are handy when you’re trying to focus on the details of a far-off subject. Telephoto lenses appear to have a much shallower depth of field than wide-angle and midrange lenses, and you can use them to blur out background details to isolate a subject. Telephoto lenses are commonly used for sports and wildlife photography. The shallow depth of field also makes them one of the top choices for photographing portraits.

Like wide-angle lenses, telephoto lenses also have their quirks, such as perspective distortion. As you may have guessed, telephoto perspective distortion is the opposite of wide-angle distortion. Because everything in the photo is so far away with a telephoto lens, the lens tends to compress the image. Compression causes the background to look closer to the subject than it actually is. Of course, you can use this effect creatively. For example, compression can flatten out the features of a model, resulting in a pleasing effect. Compression is one of the main reasons photographers often use a telephoto lens for portrait photography.

A standard telephoto zoom lens usually has a range of about 70 to 200mm. If you want to zoom in close to a subject that’s very far away, you may need an even longer lens. These super-telephoto lenses can act like telescopes, really bringing the subject in close. They range from about 300mm up to about 800mm. Almost all super-telephoto lenses are prime lenses, and they’re very heavy, bulky, and expensive. To keep costs lower (and in many cases due to size and weight constraints), some super-telephoto lenses have a slower aperture of f/4.0.

There are quite a few telephoto prime lenses available. Most of them, especially the longer ones (105mm and longer), are expensive, although you can sometimes find older Nikon primes that are discontinued or used — and at decent prices — such as the NIKKOR 300mm f/4.0.

The following list covers some of the most common telephoto lenses:

- NIKKOR 70–200mm f/4G VR III. This is the latest affordable professional grade Nikon alternative to the 70–200mm f/2.8G VR lens. It is sharp and has a constant f/4.0 aperture. This makes for a smaller, lighter lens when speed isn’t a necessity. Its relatively small size makes it a great high-quality lens for the D3300. This lens is designed for FX use, but is still a great fit for a DX camera like the D3300 due to its smaller size as compared to other pro telephoto lenses.

Image courtesy of Nikon, Inc.

4.6 The NIKKOR 70–200mm f/4G VR III lens.

- NIKKOR 55–300mm f/4–5.6G VR. If you need a lot of reach, but don’t have a lot of money, this lens gives you the best results in its price range. It’s a stop slower than the 70–200mm f/4 at the long end, but it’s smaller, lighter, and much less expensive. The image quality is acceptable for the price, but it’s not necessarily the best option for maximum resolving power. This is a great lens to get started with.

- NIKKOR 80–400mm f/4.5–5.6G AF-S ED VR. This newly redesigned high-power, VR image-stabilization zoom lens gives you a lot of reach. Its versatile zoom range makes it especially useful for wildlife photography when the subject is far away. As with most lenses with a very broad focal-length range, you make concessions with fast apertures and a moderately lower image quality when compared to the 70–200mm constant-aperture lenses. This lens is relatively expensive, but if you need a lot of reach, it is one of the few options for zoom lenses. This lens can also be used with FX cameras.

Close-up/macro lenses

A macro lens is a special-purpose lens used in macro and close-up photography. It allows you to have a closer focusing distance than regular lenses, which in turn allows you to get more magnification of your subject, revealing small details that would otherwise be lost. True macro lenses offer a magnification ratio of 1:1; that is, the image projected onto the sensor through the lens is the exact same size as the object being photographed. Some lower-priced macro lenses offer a 1:2 or even a 1:4 magnification ratio, which is one-half to one-quarter of the size of the original object. Although lens manufacturers refer to these lenses as macro, strictly speaking, they are not.

Nikon macro lenses are branded Micro-NIKKOR.

One major concern with a macro lens is the depth of field; when you focus at such a close distance, the depth of field becomes very shallow. As a result, it’s often advisable to use a small aperture to maximize your depth of field and ensure everything is in focus. Of course, as with any downside, there’s also an upside: You can also use the shallow depth of field creatively. For example, you can use it to isolate a detail in a subject.

Macro lenses come in a variety of focal lengths, with the most common being 60mm. Some macro lenses have substantially longer focal lengths that allow more distance between the lens and the subject. This comes in handy when the subject needs to be lit with an additional light source. A lens that’s very close to the subject while focusing can get in the way of the light source, casting a shadow.

When buying a macro lens, you should consider a few things: How often are you going to use the lens? Can you use it for other purposes? Do you need AF? Because newer dedicated macro lenses can be pricey, you may want to consider some less expensive alternatives.

It’s not absolutely necessary to have an autofocus lens. When shooting very close up, the depth of focus is very small, so all you need to do is move slightly closer or farther away to achieve focus. This makes an autofocus lens a bit unnecessary. You can find plenty of older manual focus (MF) macro lenses that are very inexpensive, but that have superb lens quality and sharpness.

Nikon has a very strong lineup of macro lenses that offer full functionality with the D3300. They range from normal to telephoto in both VR and non-VR versions and at all price points. The choices include the 40mm f/2.8G, 60mm f/2.8G, 85mm f/3.5G VR, and the 105mm f/2.8G VR when you need some extra reach.

Image courtesy of Nikon, Inc.

4.7 The Micro-NIKKOR 40mm f/2.8G macro lens.

4.8 I shot this macro photo of a leaf covered with raindrops using a Nikon 60mm f/2.8G macro lens. Exposure: ISO 450, f/8, 1/250 second.

Fisheye lenses

Fisheye lenses are ultrawide-angle lenses that aren’t corrected for distortion like standard rectilinear wide-angle lenses. These lenses are known as curvilinear, meaning that straight lines in your image, especially near the edge of the frame, are curved. Fisheye lenses have extreme barrel distortion. What makes fisheye lenses appealing is the very thing we try to get rid of in other wide-angle lenses.

Fisheye lenses cover a full 180-degree area, allowing you to see everything that’s immediately to the left and right of you in the frame. You need to take special care so that you don’t get your feet in the frame, which often happens when you use a lens with a field of view this extreme.

Fisheye lenses aren’t made for everyday shooting, but with their extreme perspective distortion, you can achieve interesting, and sometimes wacky, results. You can also de-fish or correct for the extreme fisheye by using image-editing software such as Photoshop, Capture NX or NX 2, and DxO Optics. The result of de-fishing your image is that you get a reduced field of view. This is akin to using a rectilinear wide-angle lens, but it often yields a slightly wider field of view than a standard wide-angle lens.

Two types of fisheye lenses are available: circular and full frame. Circular fisheye lenses project a complete 180-degree round image onto the frame, resulting in a circular image surrounded by black in the rest of the frame. A full-frame fisheye completely covers the frame with an image. The 16mm NIKKOR fisheye is a full-frame fisheye on an FX-format dSLR. Sigma also makes a few fisheye lenses in both the circular and full-frame variety. A couple of companies that were initially founded in the former Soviet Union (Zenitar and Peleng) still manufacture relatively high-quality but affordable manual-focus, fisheye lenses. Autofocus is not really necessary on fisheye lenses, given their extreme depth of field and short focusing distance.

4.9 An image of the Texas State Capitol taken with a Nikon 10.5mm fisheye lens. Notice the pronounced curving distortion at the horizon line. Exposure: ISO 100, f/16, 1/125 second.