CHAPTER SEVEN

TEACH THEM HOW TO MANAGE THEMSELVES

I know I am great. I don’t need my boss to tell me I’m great. But I’m great at my talents, whereas you are probably great at your talents. We are both great in our own way. Me? I’ve always been the athlete who trains harder than anyone else, and that’s who I am at work: the guy who will come in the earliest, stay the latest, do the heaviest lifting. But I’m not too good with details. I’ll probably mess up on some of the details. Sorry. But I still know I’m great.

—Millennial

Here’s a story a manager in a large research company told me: “The first time I interviewed this one employee, she told me, ‘I think you are going to be really impressed.’ Then, when I hired her, she told me the same thing. The third time she repeated, ‘I think you are going to be really impressed,’ was on her first day of work. Well, I was, and I wasn’t. She was very smart and she did high-quality work, in a whole other league than people with much more experience. But her work habits were horrendous. Where do I begin? She came in late, left early, took long breaks, and missed days of work. She lied about it, too, always making excuses. She dressed inappropriately. She cursed a blue streak. She did great work, but very little of it. So I was impressed, and then again I wasn’t. In some ways, she was superb. But she was just lacking in the basics.”

Millennials are often amazingly advanced in their knowledge and skills at a very young age, yet they often lack maturity when it comes to the old-fashioned basics of productivity, quality, and behavior. What’s worse, managers often report that Millennials tend to be unaware of gaps in these basic skills and are completely unconcerned about it. In response to this gap in skills, some managers just become frustrated. After all, when Millennials come to the workplace, shouldn’t they already be mature enough to arrive on time, dress appropriately, practice good manners, stay focused on their key tasks, and do lots of work very well at a good, steady pace? Should managers be expected to teach them these sorts of things? As a restaurant manager put it: “Nobody taught me how to wipe my nose in my jobs. I had to learn how to manage myself.”

That may be. But if you are the boss, then this gap in skills is your problem. If you manage Millennials who lack some of the basics of self-management, I’m sure you are frustrated, too. Here’s what you need to do: Help them. Lift them up. Make them better. Teach them to care about the basics. Teach them to be more aware of those gaps in their repertoires. Teach them to fill those gaps, one at a time. Teach them how to manage themselves.

Teach Them to Make the Most of Their Time

One of the paradoxes of the Millennial Generation is that they are always in a hurry to get things done in the short term, but when it comes to longer-term goals, they often seem to lack a sense of urgency. “They don’t realize how fleeting time is, how fast it goes,” a senior executive in a major information systems company told me. But aren’t Millennials plugged into today’s fast pace even more than those from older generations? I asked. “That’s true. They expect everything to be instant. They don’t think in months or weeks; they think in hours and minutes. But they don’t realize how little time there really is available to us. Every minute you spend on one thing is a minute you can’t spend on something else. Some things take a long time to do, and if you don’t do them right, sometimes they take even longer than they should. These young people spend way too much time on all the wrong things. They have to learn to spend their time more efficiently. It’s about setting priorities.”

Help Them Set Priorities

Setting priorities is usually step one in most time management programs and seminars. If you have limited time and too much to do, then you need to set priorities—an order of precedence or preference—so that you control what is done first, second, third, and so on. That setting priorities is the key to time management is obvious to most professionals. The hard part is teaching Millennials how to set priorities. According to that information systems company senior executive: “It’s very hard to teach them how to set big-picture priorities because they don’t have the big-picture information.” He gave this example: “Most of our people work on multiple projects with different managers. When one of the senior managers pulls a programmer onto a project, he might be pulling the programmer off another project. Should that programmer—maybe a twenty-five-year-old kid with less than two years here—decide which is a priority? Should that programmer be put in that position? Of course not. How is he supposed to know that the project he’s working on for a junior manager is actually more important to the company’s big picture and should take priority over the project for the senior manager?”

When it comes to big-picture priorities, set clear priorities with Millennials, and communicate those priorities relentlessly. Make sure your Millennials are devoting the lion’s share of their time to first and second priorities. When it comes to setting day-to-day priorities, teach Millennials how by setting priorities together with them. Let them know your thinking process. Walk through it with them: “This is first priority because X. This is second priority because Y. This is low priority because Z.” Over time, you hope they learn. Until they learn, you have to keep making decisions for them, or at least together with them. Teach Millennials to postpone low-priority activities until high-priority activities are well ahead of schedule. Those are the time windows during which lower-priority activities can be accomplished, starting with the top lower priorities, of course. Time wasters, on the other hand, should be eliminated altogether whenever possible.

Help Them Eliminate Time Wasters

Everyone has time wasters, but nobody can afford them, least of all people in the early stages of their careers who are eager to succeed but are also quite easily distracted. The best gift you can give Millennials is helping them to identify their big time wasters and eliminate them altogether. Probably the best tool for identifying time wasters is an old-fashioned time log or diary, in which an individual keeps track almost minute by minute of what she is doing. The idea is that each time the person changes from one activity to another, she notes briefly the time and the activity. Here’s an example:

| 8:00 | Sat down at my desk, turned on computer |

| 8:10 | Got up to use bathroom and get coffee |

| 9:15 | Sat back down at desk, opened e-mail. |

| 9:30 | Started preparing response to e-mail from Client Jones |

| 9:40 | Incoming phone call from Friend Smith |

| 10:15 | Continued preparing response to e-mail from Client Jones |

| 10:25 a.m. | Got up to use bathroom and get another cup of coffee |

The time log is useful only if the user faithfully logs every activity precisely. Used properly, three or four days is all it takes to get a reality check on how a person is spending her time. How much time is spent on first, second, or third priorities? What are the big time wasters that can be eliminated to free up time?

Remember that Millennials treasure time above all other nonfinancial rewards. When you help them eliminate time wasters and limit the time they spend on low priorities, you are helping them focus their time on top priorities and giving them free time they otherwise would have wasted. That is a reward that keeps on giving. They’ll really appreciate it.

When helping Millennials identify time wasters to eliminate, don’t mistake distractions for time wasters. They may or not be. Remember that Millennials are used to multitasking—they’ve been doing their homework for years with an MP3 player in one ear and a cell phone buzzing text messages on the table. Just because it might be distracting to you doesn’t mean it is distracting to them. If the task in question is being performed well within expected time frames, then the employee is probably not distracted. Pay attention to which of the so-called distractions help them remain absorbed in their tasks at work, as opposed to those that draw their attention away.

Teach Them How to Live by a Schedule

“For people who are supposed to be in a hurry all the time, Millennials sure take their time getting to work. They are the worst offenders bar none when it comes to tardiness,” said a manager in a medical laboratory. She continued, “They take their time getting through their work, too. Deadlines mean little to them. They just say, ‘Oh, yeah, sorry it’s late.’ I say, ‘That’s not okay,’ and they say, ‘Yeah, I’m really sorry.’ Then it’s late the next time, too. Most of them do a great job. They’re just always late doing it.”

Tardiness, whether it is coming late to work or missing deadlines, is one of managers’ top complaints about Millennials. And while managers often attribute Millennials’ tardiness to a blasé attitude and a lack of care, consideration, or diligence, our research shows that Millennials’ tardiness is almost always due to a lack of good planning. When it comes to planning time, there is really no better tool than a good old-fashioned schedule. Once again, you have to teach them the basics.

Here’s why. On one hand, what Millennials really want, when it comes to time management, is greater freedom. On the other hand, they grew up as the most overscheduled generation in history, so they actually like schedules. The problem is that Millennials are used to schedules customized to their particular life circumstances, needs, and wants. One Millennial told me: “I’ve been working here for four months, and their early morning schedule is hard for me. I’m used to staying up all night writing papers and studying for exams. If you had to skip a class or show up to class late because you’ve been up all night studying, nobody was going to chew your head off. If you needed an extension on a paper, you could get one. Once I had an exam rescheduled because I wasn’t ready.”

Ultimately, Millennials want more flexibility about when they work, more control over their time while they are working, and more free time outside work. Thus, in order to get what they want, they need a lot of help doing lots of work very well, very fast while they are at work. The trick to doing that is teaching them how to use a schedule to better plan their hours, minutes, and seconds around their priorities—inside and outside work.

A smart retail manager told me this story about using schedules to help a Millennial arrive at work on time: “When I have people who are chronically late, I’ve learned that usually they need help being on time. I just had this experience with a young employee, Paul. Paul was always on time for the evening shift but always late for the morning shift. At first I thought he was trying to get me to give him the late shift every week. But when I talked to him, I found out that he had never really tuned in to the fact that it took him longer to get ready for and to get to work in the morning than in the afternoon. I mean, he knew it in the back of his head, but he had never really taken it into account.”

The retail manager continued: “I had to help Paul learn how to be on time. So I took out a piece of paper and we wrote a schedule, working backward from 8:00 a.m.: ‘Walk in the front door at work at 7:55 a.m. Leave Dunkin’ Donuts parking lot by 7:35 a.m. Pull in to Dunkin’ Donuts parking lot by 7:25 a.m. Leave home by 7:10 a.m. Get back from walking dog by 7:00 a.m.’” Is it appropriate to help an employee plan out details as personal as what time he will walk his dog?

No matter how rigorously employees schedule their work time, if they can’t manage their nonwork time, they often come late to work, leave early, call in sick, spend work time doing nonwork activities, and so on. I asked the retail manager how this approach worked with Paul. “I was afraid he would be insulted, but the look on his face was pure gratitude. He was saying, ‘That really helps me, that really helps me.’ Not only has he been chronically on time ever since we did the schedule, but now he counts out everything backward in his day planner. I offered to get him a PDA as a reward for doing so great, but he said ‘no thanks.’ He is attached to that little day planner. Those are habits that really stuck for him.” Hooray for Paul! Hooray for this manager!!

Most Millennials report they have more to do at work than they can fit into their work schedules and more they want to do outside work than they can do in their limited free time. Many are chronically overtired and seriously overscheduled. One Millennial told me: “I don’t stay past five or six at work because I don’t have time to stay. There is the dance class I am taking, the dance class I am teaching, and all these new friends and my old friends. I’m up until 3 a.m., and then I’m at my desk by 9 a.m., Monday through Saturday. It’s not like I’m not working. I’m so busy all day at work, I don’t have any time left to be in the game.”

When teaching Millennials how to manage their schedules, you need to start somewhere. Sleeping is where I always start. Tell them to block fifty-six hours every week for sleeping, ideally in eight-hour increments. Block another hour a day for downtime, ideally around the sleep time. That leaves them with 105 hours to be awake and “in the game” each week. Then what? If they don’t plan their nonwork time leading up to the time they walk in the door at work, there is a good chance they’ll be late for work. If they don’t plan their nonwork time after work, there is a good chance they’ll be late the next day or else be stressed and distracted. The only way to harmonize work time and nonwork time is to keep one schedule. Teach them this basic fact of life, and they will probably be very grateful.

Teach Them How to Make a Plan

Schedules are useful tools only if they reflect accurate planning. Often what looks like a perfectly good schedule turns out to be a fantasy—a wishful projection for how we’ll spend our very limited time.

Here’s a story told to me by the manager of a new Millennial employee in a massive international consumer products company: “Greg, an ambitious young man, was missing deadlines from the get-go on his first project. I was thrown off because, when he started the project, he had impressed me with a plan very carefully broken out into short-term goals with short-term deadlines along the way.” When the manager sat down with Greg to talk about the missed deadlines, they both realized that the initial schedule Greg had drafted was based on unrealistic time lines. “They were all just guesses. Uneducated guesses at that. The big lesson for Greg was that timetables are no good if you don’t figure out how long each goal is actually going to take to complete. After their conversation, the manager explained, “Greg was able to make new timetables and meet every one of those very realistic new short-term deadlines.”

Before you can make a realistic plan, you have to know how long each task is actually going to take. That sounds obvious, but we’ve seen over and over again in our research that Millennials miss deadlines because they are missing this basic step. “The big lesson for me,” said the manager at the consumer products company, “was that you really have to teach them how to make a plan. Greg knew enough to take a big project and break it down into a timetable, and he knew enough to make a plan. But he just didn’t know how to make a plan.”

Teach them how. Teach them how to start with a big project, how to break it into manageable tasks, estimate accurately how long it will take them to complete each of the tasks, and then set a timetable of short-term deadlines based on those realistic estimates.

Sometimes Millennials resist planning because they are so certain that things will change anyway. In an uncertain world, what’s the point in planning? It’s worth explaining to them that one of the hidden benefits of plans and schedules is that they can be used by managers to provide employees with more flexibility while still strictly enforcing deadlines. But also let Millennials know you understand that, no matter how great the plan, they are always subject to real-life interruptions. Emergencies, wild-goose chases, and distractions often spring up and disrupt the progress of a perfectly realistic plan. Teach Millennials not to be thrown off when real-life interruptions veer them off course from their well-made plans. Teach them to pay close attention to real life and be prepared to revise and adjust their plans every step of the way.

Teach Them to Take Notes and Use Checklists

A young employee recently shared this story with me: “There’s a lot to keep track of at work. It would help me a lot if they would give me step-by-step instructions. I mean, whose job is it to make sure we do our jobs right? I’m trying pretty hard, but you don’t get an A for effort around here. Sometimes I’ll ask them, ‘Could you give me instructions so I don’t waste a bunch of my time?’ You’d think they’d like that, but they say, ‘Look, I can’t do your job for you. I shouldn’t have to tell you how to do your job.’ That makes no sense. How am I supposed to do my job if you don’t tell me how?”

This Millennial is right. It’s not enough to teach Millennials to use schedules and make plans. You should also teach them to take notes and use checklists to do their jobs properly. Managers often complain that Millennials are full of energy and gumption, but they have a hard time focusing that energy on the work that needs to be done. Managers report that, even when Millennials do high-quality work in a timely manner, they often overlook important details or leave out important pieces of otherwise finished results. Our research shows that when managers require Millennials to take notes and make rigorous use of checklists, their error rates go down, quality goes up, and assignments are more likely to be completed in their entirety.

Teach Them to Take Notes

“In one ear and out the other,” said a construction supervisor in a major real estate development company. “I would say to this one guy over and over again, ‘The details really matter.’ He was nodding his head, but I couldn’t tell if he was nodding to me or nodding with the music he was listening to. So finally I started making him take notes whenever I talked to him. Since he didn’t have anything to write with but I noticed he was always on his cell phone texting, I told him, ‘Send yourself a text message.’ He focused on me like he never had before, texting into his phone the gist of what I was saying. Finally I said, ‘Send me a copy of that,’ and that’s how that started. Now he takes notes on his cell phone and sends a copy to me and to him. I print them out, and I’ll go back to him the next day, with his text message in hand, and it serves as a great reference. He usually grabs that sheet of paper, gives it a look-over, and tucks it in his back pocket. I see him checking it later as he’s going about his business. I think it helps him focus. Sometimes I take his text message and turn it into a checklist to use with all the guys. Checklists help them focus.”

Checklists are very common in workplaces where there is little room for error: operating rooms, airplane cockpits, nuclear weapons launch sites, accounting firms, and so on. Of course, checklists are useful only if they are used.

Help Them Use Checklists

A lead flight attendant for a major airline gave me this example: “The younger crew members are not lazy. I left the preflight safety demonstration to one attendant because she had been rehearsing it so much and she really wanted to practice it live. I think she had been with us for only a few weeks. When she did the demonstration, she practically sang it. Passengers looked up and listened, which is pretty unusual. But she forgot to do electronic devices. While we were taking off, I realized there were passengers still on the phone and working on computers and a kid playing a video game. These are huge FAA violations. We have procedures and checklists, of course, but if the person in charge isn’t really making sure people use them, then they don’t actually serve their purpose.”

Here’s another example, provided by a senior manager in a major accounting firm: “We are an accounting firm, so we have to use checklists. Even with all of our checklists, the less experienced staff will hand in work product that’s not complete. Sometimes they know it’s not complete. They’ll even attach a note saying, for example, ‘Section 4b is missing key pieces of information and section 5c is blank. Please complete,’ like I am supposed to finish their work for them. Other times they don’t even know it’s not complete. I’m not sure which is worse. Either way, about half the time, I would find myself finishing up work for them before it could actually be submitted. I called it ‘delegating the work back up.’”

Our research shows that turning in incomplete work is a common complaint about Millennials. What is the solution? Managers in these cases need to treat the delivery of incomplete work as an intermediate step, just another teachable moment, and another chance to get them back to the basics of self-management. Sometimes you need to teach them how to finish a product.

“When they try delegating work back up to me now, I will go over the checklist with them. Section 4b is not done until you have every piece of information. Section 5 is not done if section 5c is blank. That’s when you have to make a checklist for the checklist. Sometimes they need a checklist for the checklist for the checklist.”

Teach Millennials to take notes. Teach them how to take notes, too. Teach them to turn their notes into checklists to guide them. If you already have checklists, teach Millennials to follow checklists as step-by-step instructions to help them ensure quality and completeness in their work. If necessary, help them make checklists for the checklists. But remember that the real trick is teaching them to actually use the checklist. Sometimes you have to teach them that the reason it’s called a “checklist” is because, as you complete each item, you need to take a pen and “check” it.

Teach Them the Values of Good Workplace Citizenship

One Millennial shared this with me: “Somebody told me if you are idealistic when you are old, you are stupid, but if you are cynical when you are still young, then you just suck. I’m definitely idealistic, but I guess I kind of suck, too, because I’m also kind of cynical already.”

Indeed, idealism is a privilege and burden of youth. But Millennials’ idealism may look very different from that of generations past. All the leading research shows Millennials are more idealistic than any other new youth cohort since the first wave of Baby Boomers came of age in the 1960s. Millennials are more concerned about the well-being of the planet, humankind, and their communities than older cohorts were in their twenties. Most Millennials say there are causes and values they believe in enough that they would be willing to sacrifice their own time, money, comfort, and even well-being. They often look to values issues when they are considering a new job: Do they believe in the company’s mission? Do they approve of how you do business? This, I believe, is good news.

What is often confusing to managers is that they have a hard time pinning down Millennials on the values spectrum in a way they can understand. “When I’m hiring young entry-level employees, I’m looking for a good values fit,” said a senior executive in a leading energy services company. “With this generation, it seems like anything goes, more or less. No respect for tradition, no respect for their elders, no respect for experience, no respect for all the old-fashioned values: discretion, diligence, courtesy, honesty. You pick the clean-cut kid with Eagle Scout on his résumé, and he shows up late to work, bad-mouths his co-workers, and steals the stapler off your desk. Then you look at this long-haired kid who is listening to music on his MP3 player all day and he shows up to work early, works hard, stays late, says ‘yes sir’ and ‘yes ma’am’ and ‘please’ and ‘thank you.’ It used to be that I could pick them out of a crowd. Not anymore. Not with this generation. How do you find the Good ones? I mean the capital G good ones.”

Managers tell us every day that they have a hard time understanding how Millennials look at traditional values issues. Are they the new idealists portrayed by some observers, or are they the post-values generation for whom anything goes? Over and over again, we find that Millennials’ ideals tend to be rather idiosyncratic. They are products of an information environment that allows them to mix and match seemingly unrelated or incompatible beliefs. Like everything else in their lives, Millennials customize their deep inner values. For example, it is not uncommon to find a Millennial who considers himself a person of faith, but not one you would likely recognize. This Millennial explained, “I was born and raised Baptist, and I am still Baptist. I go to church sometimes with my parents to supercharge my spirit. But mostly I’m into Buddhist teachings right now. To me there is nothing inconsistent about that. It’s my own religion, I guess.”

Given this inscrutable nature, how can managers identify Millennials who are more likely to manifest those good old-fashioned values the senior executive was talking about above: discretion, diligence, courtesy, and honesty? As he put it, “How do you find the good ones?”

Our research shows that you can’t and you shouldn’t even try. You simply cannot divine deep inner values from interviews, tests, recommendations, and résumés. In fact, trying to figure out who Millennials are deep inside is the wrong tactic. How can you possibly figure out what their minds and spirits are really like? How can you figure out what their inner motivations really are? You are not qualified to do so. And I would argue that it’s really none of your business anyway.

“So, can you teach them traditional values?” the senior executive asked me. Here’s what we’ve learned. You cannot—and should not—teach them what to believe, but you can certainly teach them how to behave. It’s not really your place to teach them values. But it is certainly your place to teach them how to be good citizens within your organization. Where do you start?

Define What It Means to Be a Good Citizen in Your Company

The CEO of a small software company I’ve worked with gained some notoriety a few years back with his “no-jerks” policy. What did that mean exactly? According to one manager who worked for that CEO, “It was a little vague, but it was meant to capture those intangibles like your attitude, how you talk to people, how you treat people. Not exactly what kind of person you are, but how you conduct yourself with colleagues, with customers, with vendors. When something comes up, do you try to blame other people? Are you saying nasty things behind other people’s backs? Do you make excuses? Are you cutting out when everybody else is busting their humps staying all night?” Is a no-jerks policy really so much more vague than encouraging people to practice discretion, diligence, courtesy, and honesty? Maybe a little bit. But these values mean different things to different people. That’s why they can be so hard to teach. Still, such intangible elements of performance often matter a lot to managers and have a big impact on an employee’s ability to succeed in a particular organization.

What does it really mean to be a good citizen in your workplace? The key is to create shared meaning through shared language and experience. In the military, enlisted people are taught to salute and call officers sir and ma’am. One trend on the rise in the workplace is etiquette training, in which young employees are taught good old-fashioned manners, like saying “please” and “thank you.” Safeway caused a stir back in the late 1990s when they asked store employees to make eye contact with customers and smile. It was controversial, but at least the requirement was clear.

Decide what really matters in your organization, and keep it simple. Whatever values you want them to practice, you have to do the hard work of making the intangible more tangible. What do discretion, courtesy, honesty, and self-sacrifice actually look like in your workplace? Describe it. Spell it out, and break it down for them.

But one word of caution: Millennials have giant BS detectors. If you want to teach them about good workplace citizenship, you had better not act like a jerk. As the manager I mentioned earlier said, the “no-jerk” policy “put a lot of pressure on those of us in the leadership team to not act like jerks, which was good I think. Everyone has their moments, and you would definitely hear about it from some of the younger folks who don’t really hold back. You’d get this: ‘Who’s acting like a jerk now?’ So you definitely had to walk the talk.”

You Can’t Teach Good Judgment, But You Can Teach the Habits of Critical Thinking

Managers often tell us that the biggest constraint on maximizing young workers is their lack of seasoned judgment.

What is good judgment anyway? It’s not the same thing as sheer brain power, mental capacity, or natural intelligence. It’s not a matter of accumulated knowledge or memorized information. It is more than the mastery of techniques and tools. In very simple terms, good judgment is the ability to see the connection between causes and their effects. Going forward, good judgment allows one to project likely outcomes—to accurately predict the consequences of specific decisions and actions. In retrospect, good judgment allows one to work backward from effects to assess likely causes, to figure out what decisions and actions led to the current situation.

One senior executive in a large media company said: “Good judgment. That’s the ultimate. I don’t want my young employees to improvise most of the time. I want them to follow our established procedures. But we don’t have procedures for everything. I can try hard to anticipate situations they are likely to encounter and help them prepare for those situations. But I can’t anticipate every possible situation. There are times when they just have to use good judgment. But they are just too young and don’t have enough experience to have good judgment.”

Putting aside those rare people who are wise beyond their years, are age and experience prerequisites for good judgment? The answer is, in part, yes. Experience means participating—feeling, tasting, hearing, seeing, smelling—in the unfolding of life events. Life events unfold over time. By definition, the more time passes, the more experience one has. That’s why experience and age often lead to improved judgment. Of course, you can’t fast-forward time or wait for your Millennial employees to grow older and acquire judgment. So how can you improve their judgment?

Expose Them to New Experiences

One factor in determining good judgment is the quality of a person’s experiences. Are his experiences diverse or monotonous? Deep or glancing? Has he experienced richly many different kinds of causes and been able to observe their various effects? This is the logic behind rotation programs in which employees are given a series of relatively short-term assignments (usually a matter of months) in different types of operations in different parts of the company, sometimes in different parts of the world. The idea is exposure, plain and simple.

If you have the resources, give Millennials more experience faster by putting them on rotation programs. Even with limited resources, you can give them more experience through more diverse and deep exposure. Move them around to different parts of your company once in a while, even if that means the other side of the building. Let them try out different tasks, responsibilities, and projects. Encourage them to interact with different employees, vendors, and customers.

Teach Them to Be Strategic

The single most important factor in good judgment is how a person thinks about her life experiences. Does she think about cause and effect? Does she stop and reflect before making decisions and taking actions? Does she project likely outcomes in advance? Does she look at each decision and action as a set of choices, each with identifiable consequences?

If you’ve played chess or any other game of strategy, you know what I mean. The key to success is thinking ahead. Before making a move, you play out in your head the likely outcomes, often over a long sequence of moves and countermoves. If I do A, the other player would probably respond with B. Then I would do C, and he would probably respond with D. Then I would do E, and he would probably respond with F. And so on. This is what strategic planners call a decision/action tree because each decision or action is the beginning of a branch of responses and counter-responses. In fact, each decision or action creates a series of possible responses, and each possible response creates a series of possible counter-responses.

Teach Millennials to be strategic by using decision/action trees every step of the way. Teach them to think ahead and play out the likely sequence of moves and countermoves before making a move: “If you take this decision or action, who is likely to respond, how, when, where, and why? What set of options will this create? What set of options will this cut off? How will it play out if you take this other decision/action instead?

Teach Them to Look at Past Experiences—Their Own and Others’

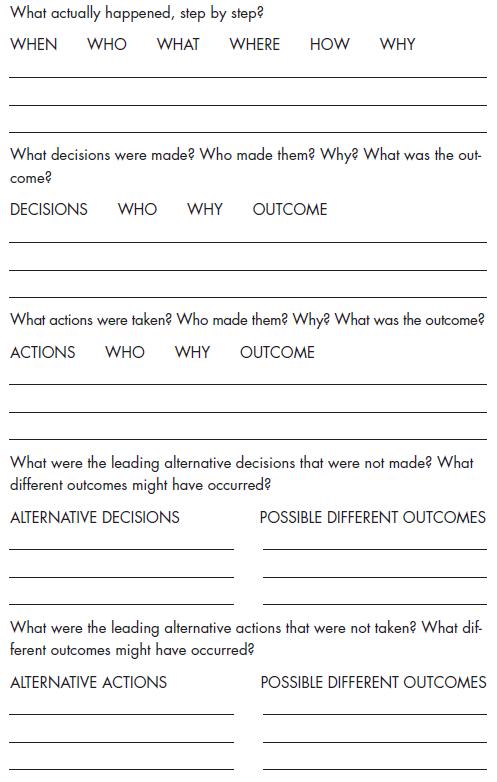

The senior executive of a media company asked, “How does a person learn real-life lessons faster than he can experience real life? Is there any way to jump-start this process?” One way is to learn from the life experiences of others or from history. This is why the case study method is used by most business schools. Real company cases are presented to students in detail. Who were the key players? What were their interests and objectives? What happened? How did it happen? Where? When? What were the outcomes? Students are then taught to apply the methods of critical thinking to the facts of the case. They are taught to suspend judgment, question assumptions, uncover the facts, and then rigorously analyze the decisions and actions taken by different key players in the case study. The pedagogy is simple: look at the outcomes, and trace them back to see the chains of cause and effect.

You can jump-start their learning by giving Millennials a little taste of business school in real life. Give them real cases to study, and teach them to use the case study method. Teach them to apply the methods of critical thinking to the real-life experiences of others. Give them a simple one-page worksheet to analyze real cases.

Analysis Worksheet

Perhaps the most important thing you can do to jump-start Millennials’ development of good judgment is teaching them to scrutinize their own experiences during and after they actually occur. Teach them to stop and reflect after making decisions and taking actions. Teach them to stop and reflect on outcomes and consequences. This is the essence of the lessons-learned process that is ubiquitous in the military and intelligence agencies. Every mission is subjected to intense scrutiny immediately after the fact. Leaders at all levels involved in a mission are expected to go over every decision and action, step by step, to determine exactly what happened and why. Then they meet to discuss and debate these decisions and actions. As one army officer told me: “It is our duty to second-guess and third-guess and fourth-guess and fifth-guess every move we make.” Lessons learned from real experience are meant to guide the planning and execution of future missions. Said the army officer: “We are at war, so we use lessons learned the next day or the same day sometimes. This is real-time learning in action.”

Teach Millennials to apply the lessons-learned process to every “mission” they undertake, to every move they make. Ask them to subject their decisions and actions to much greater scrutiny every step of the way: What were the specific causes of each outcome or consequence? You can even give them the same one-page worksheet to help them analyze their own decisions and actions.

Self-Evaluation Is the Beginning, Middle, and End of Self-Management

Rigorous self-evaluation is not just a key component of learning good judgment. It is the beginning, middle, and end of self-management. It is the essential habit of self-improvement. If you teach Millennials one thing, teach them to make a commitment to constant, rigorous self-evaluation. Teach them to assess their use of time, the productivity and quality of their work, and their behavior.

Teach them to ask themselves these questions:

- Productivity: Am I getting enough work done fast enough? What can I do to finish more work faster? Should I revisit my priorities? Do I need to focus my time better? Do I need to postpone low-priority activities? How can I eliminate time wasters? Do I need better time budgets? Do I need to make better plans?

- Quality: Am I meeting or exceeding guidelines and specifications for my tasks and responsibilities? What can I do to improve my work? Do I need to make better use of checklists? Do I need to start adding some bells and whistles to my work product?

- Behavior: What can I do to be a better workplace citizen? Are there substandard behaviors I can eliminate? Are there superstar behaviors I can start adding? Should I be taking more initiative or less? How can I take more initiative without overstepping my bounds?

Of course, self-evaluation is an engine of self-improvement only if you use the information you’ve learned from it. So teach them to focus on their self-evaluation and really use what they learn. Teach them to start on one little goal at a time—the smaller the better. For example, if someone wants to become a better workplace citizen, that’s a pretty big bite to chew on. Carve it up. Encourage him to start with something simple such as: “Step one, stop swearing. Practice saying ‘dagnabbit’ and ‘gee whiz’ instead of curse words.” Once he has met that goal, encourage him to take on another small bite: “Step two, stop bad-mouthing your colleagues. Practice biting your tongue when you feel the urge to say something nasty. Practice saying nice things about people.”

And always remind them that self-management and self-improvement come one small step at a time. It’s a never-ending process because there is always room to improve.